Omeprazole: Difference between revisions

→Multiple unit pellet system: Removing slimy salesman talk |

|||

| Line 198: | Line 198: | ||

===Multiple unit pellet system=== |

===Multiple unit pellet system=== |

||

Omeprazole tablets manufactured by AstraZeneca (notably Losec/Prilosec) are formulated as a "Multiple Unit Pellet System" (MUPS). Essentially, the [[Tablet (pharmacy)|tablet]] consists of extremely small enteric-coated granules (pellets) of the omeprazole formulation inside an outer shell. When the tablet is immersed in an aqueous solution, as happens when the tablet reaches the stomach, water enters the tablet by [[osmosis]]. The contents swell from water absorption causing the shell to burst, releasing the enteric-coated granules. For most patients, the multiple-unit pellet system is of no advantage over conventional enteric-coated preparations. Patients for which the formulation is of benefit include those requiring [[nasogastric tube]] feeding and those with difficulty swallowing ([[dysphagia]]) because the tablets can be mixed with water ahead of time, releasing the granules into a slurry form, which is easier to pass down the feeding tube or to swallow than the pill.{{Citation needed|date=July 2009}} |

Omeprazole tablets manufactured by AstraZeneca (notably Losec/Prilosec) are formulated as a "Multiple Unit Pellet System" (MUPS). Essentially, the [[Tablet (pharmacy)|tablet]] consists of extremely small enteric-coated granules (pellets) of the omeprazole formulation inside an outer shell. When the tablet is immersed in an aqueous solution, as happens when the tablet reaches the stomach, water enters the tablet by [[osmosis]]. The contents swell from water absorption causing the shell to burst, releasing the enteric-coated granules. For most patients, the multiple-unit pellet system is of no advantage over conventional enteric-coated preparations. Patients for which the formulation is of benefit include those requiring [[nasogastric tube]] feeding and those with difficulty swallowing ([[dysphagia]]) because the tablets can be mixed with water ahead of time, releasing the granules into a slurry form, which is easier to pass down the feeding tube or to swallow than the pill.{{Citation needed|date=July 2009}} |

||

The granules are manufactured in a [[fluid air bed]] system. Sugar spheres in suspension are sequentially sprayed with aqueous [[Suspension (chemistry)|suspension]]s of omeprazole, a protective layer, an enteric coating and an outer layer to reduce granule aggregation. The granules are mixed with other [[excipient]]s and compressed into tablets. Finally, the tablets are film-coated to improve the stability and appearance of the preparation. |

The granules are manufactured in a [[fluid air bed]] system. Sugar spheres in suspension are sequentially sprayed with aqueous [[Suspension (chemistry)|suspension]]s of omeprazole, a protective layer, an enteric coating and an outer layer to reduce granule aggregation. The granules are mixed with other [[excipient]]s and compressed into tablets. Finally, the tablets are film-coated to improve the stability and appearance of the preparation. |

||

Also available in a liquid suspension form, from a compounding pharmacy. |

|||

===Immediate release formulation=== |

===Immediate release formulation=== |

||

Revision as of 07:42, 24 June 2013

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, IV |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 35–76%[2][3] |

| Protein binding | 95% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP2C19, CYP3A4) |

| Elimination half-life | 1–1.2 hours |

| Excretion | 80% Renal 20% Faecal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.122.967 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H19N3O3S |

| Molar mass | 345.4 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Omeprazole (INN) /oʊˈmɛprəzoʊl/ (Prilosec and generics) is a proton pump inhibitor used in the treatment of dyspepsia, peptic ulcer disease (PUD), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD/GERD), laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) and Zollinger–Ellison syndrome. Omeprazole is one of the most widely prescribed drugs internationally and is available over the counter in some countries.

Medical uses

Omeprazole is used to treat gastroesophageal reflux disease, gastric and duodenum ulceration, and gastritis.

As a therapeutic adjuvant in treating Helicobacter pylori related ulcers

Omeprazole is combined with the antibiotics clarithromycin and amoxicillin (or metronidazole in penicillin-hypersensitive patients) in the 7–14 day eradication triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori. Infection by H. pylori is the causative factor in the majority of peptic ulcers.[4]

Adverse effects

Some of the most frequent side effects of omeprazole (experienced by over 1% of those taking the drug) are headache, diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, dizziness, trouble awakening and sleep deprivation, although in clinical trials the incidence of these effects with omeprazole was mostly comparable to that found with placebo.[5] Other side effects may include iron and vitamin B12 deficiency, although there is very little evidence to support this.[6]

Proton pump inhibitors may be associated with a greater risk of osteoporosis related fractures[7][8] and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea.[6][9] By suppressing acid-mediated breakdown of proteins, antacid preparations (such as omeprazole) lead to an elevated risk of developing food and drug allergies. This happens due to undigested proteins then passing into the gastrointestinal tract where sensitisation occurs. It is unclear whether this risk occurs with only long-term use or with short-term use as well.[10] Patients are frequently administered the drugs in intensive care as a protective measure against ulcers, but this use is also associated with a 30% increase in occurrence of pneumonia.[6][11] The risk of community-acquired pneumonia may also be higher in people taking PPIs.[6]

Since their introduction, proton pump inhibitors (especially omeprazole) have been associated with several cases of acute tubulointerstitial nephritis, an inflammation of the kidneys that often occurs as an adverse drug reaction.[6][12][13]

PPI use has also been associated with fundic gland polyposis.[14]

The following adverse reactions have been identified during post-approval use of Prilosec Delayed-Release Capsules.[15] Because these reactions are voluntarily reported from a population of uncertain size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their actual frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure.

Systemic: Hypersensitivity reactions including anaphylaxis, anaphylactic shock, angioedema, bronchospasm, interstitial nephritis, urticaria, fever; pain; fatigue; malaise;hair loss;

Cardiovascular: Chest pain or angina, tachycardia, bradycardia, palpitations, elevated blood pressure, peripheral edema

Endocrine: Gynecomastia

Gastrointestinal: Pancreatitis (some fatal), anorexia, irritable colon, fecal discoloration, esophageal candidiasis, mucosal atrophy of the tongue, stomatitis, abdominal swelling, dry mouth, microscopic colitis. During treatment with omeprazole, gastric fundic gland polyps have been noted rarely. These polyps are benign and appear to be reversible when treatment is discontinued. Gastroduodenal carcinoids have been reported in patients with ZE syndrome on long-term treatment with Prilosec. This finding is believed to be a manifestation of the underlying condition, which is known to be associated with such tumors.

Hepatic: Liver disease including hepatic failure (some fatal), liver necrosis (some fatal), hepatic encephalopathy hepatocellular disease, cholestatic disease, mixed hepatitis, jaundice, and elevations of liver function tests [ALT, AST, GGT, alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin]

Metabolism and Nutritional disorders: Hypoglycemia, hypomagnesemia, hyponatremia, weight gain

Musculoskeletal: Muscle weakness, myalgia, muscle cramps, joint pain, leg pain, bone fracture

Nervous System/Psychiatric: Psychiatric and sleep disturbances including depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, confusion, insomnia, nervousness, apathy, somnolence, anxiety, and dream abnormalities; tremors, paresthesia; vertigo

Respiratory: Epistaxis, pharyngeal pain

Skin: Severe generalized skin reactions including toxic epidermal necrolysis (some fatal), Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme; photosensitivity; urticaria; rash; skin inflammation; pruritus; petechiae; purpura; alopecia; dry skin; hyperhidrosis

Special Senses: Tinnitus, taste perversion

Ocular: Optic atrophy, anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, optic neuritis, dry eye syndrome, ocular irritation, blurred vision, double vision

Urogenital: Interstitial nephritis, hematuria, proteinuria, elevated serum creatinine, microscopic pyuria, urinary tract infection, glycosuria, urinary frequency, testicular pain

Hematologic: Agranulocytosis (some fatal), hemolytic anemia, pancytopenia, neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, leucocytosis

Interactions

Omeprazole is a competitive inhibitor of the enzymes CYP2C19 and CYP2C9, and may therefore interact with drugs that depend on them for metabolism, such as diazepam, escitalopram, and warfarin; the concentrations of these drugs may increase if they are used concomitantly with omeprazole.[16] Clopidogrel (Plavix) is an inactive prodrug that partially depends on CYP2C19 for conversion to its active form; inhibition of CYP2C19 blocks the activation of clopidogrel, thus reducing its effects and potentially increasing the risk of stroke or heart attack in people taking clopidogrel to prevent these events.[17][18] Omeprazole is also a competitive inhibitor of p-glycoprotein, as are other PPIs.[19]

Drugs that depend on stomach pH for absorption may interact with omeprazole; drugs that depend on an acidic environment (such as ketoconazole or atazanavir) will be poorly absorbed, whereas acid-labile antibiotics (such as erythromycin) will be absorbed to a greater extent than normal due to the more alkaline environment of the stomach.[16]

St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum) and Gingko biloba significantly reduce plasma concentrations of omeprazole through induction of CYP3A4 and CYP2C19.[20]

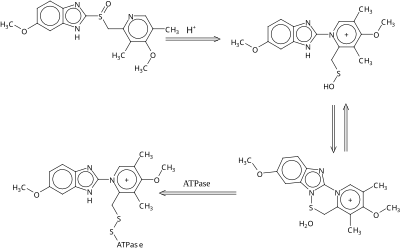

Mechanism of action

Omeprazole is a selective and irreversible proton pump inhibitor. Omeprazole suppresses gastric acid secretion by specific inhibition of the hydrogen–potassium adenosinetriphosphatase (H +, K +-ATPase) enzyme system found at the secretory surface of parietal cells. It inhibits the final transport of hydrogen ions (via exchange with potassium ions) into the gastric lumen. Since the H +, K +-ATPase enzyme system is regarded as the acid (proton) pump of the gastric mucosa, omeprazole is known as a gastric acid pump inhibitor. The inhibitory effect is dose-related. Omeprazole inhibits both basal and stimulated acid secretion irrespective of the stimulus.[21]

Pharmacokinetics

The absorption of omeprazole takes place in the small intestine and is usually completed within 3–6 hours. The systemic bioavailability of omeprazole after repeated dose is about 60%.

Omeprazole bioavailability is significantly impaired by the presence of food and, therefore, patients should be advised to take omeprazole with a glass of water on an empty stomach (i.e., fast for at least 60 minutes before taking omeprazole). Additionally, most sources recommend that after taking omeprazole at least 30 minutes should be allowed to elapse before eating[22][23] (at least 60 minutes for immediate-release omeprazole plus sodium bicarbonate products, such as Zegerid[24]), though some sources say that with delayed-release forms of omeprazole it is not necessary to wait before eating after taking the medication.[25] Plasma protein binding is about 95%.

Omeprazole is completely metabolized by the cytochrome P450 system, mainly in the liver. Identified metabolites are the sulfone, the sulfide and hydroxy-omeprazole, which exert no significant effect on acid secretion. About 80% of an orally given dose is excreted as metabolites in the urine and the remainder is found in the feces, primarily originating from bile secretion.

Measurement in body fluids

Omeprazole may be quantitated in plasma or serum to monitor therapy or to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients. Plasma omeprazole concentrations are usually in a range of 0.2–1.2 mg/L in persons receiving the drug therapeutically via the oral route and 1–6 mg/L in victims of acute overdosage. Enantiomeric chromatographic methods are available to distinguish esomeprazole from racemic omeprazole.[26][27]

Chemistry

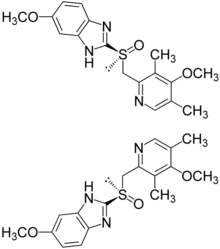

Omeprazole is a racemate. It contains a tricoordinated sulfinyl sulfur in a pyramidal structure and therefore can exist in equal amounts of both the (S)- and (R)-enantiomers. In the acidic conditions of the canaliculi of parietal cells, both are converted to achiral products (sulfenic acid and sulfenamide configurations) which reacts with a cysteine group in H+/K+ ATPase, thereby inhibiting the ability of the parietal cells to produce gastric acid.

Facing the loss of patent protection and competition from generic drug manufacturers, AstraZeneca developed and heavily marketed esomeprazole (Nexium) as a replacement in 2001.[when?] Esomeprazole is the eutomer [(S)-enantiomer] in the pure form, not a racemate like omeprazole.

Omeprazole undergoes a chiral shift in vivo which converts the inactive (R)-enantiomer to the active (S)-enantiomer doubling the concentration of the active form.[28] This chiral shift is accomplished by the CYP2C19 isozyme of cytochrome P450, which is not found equally in all human populations. Those who do not metabolize the drug effectively are called "poor metabolizers." The proportion of the poor metabolizer phenotype varies widely between populations, from 2–2.5% in African-Americans and white Americans to >20% in Asians; several pharmacogenomics studies have suggested that PPI treatment should be tailored according to CYP2C19 metabolism status.[29]

History

Omeprazole was first marketed in the U.S. in 1989 by Astra AB, now AstraZeneca under the brand names Losec and Prilosec. An over the counter brand, Prilosec OTC, is available without prescription in the US for treatment of heartburn. It is now also available from generic manufacturers under various brand names.

In 1990, at the request of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the brand name Losec was changed to Prilosec to avoid confusion with the diuretic Lasix (furosemide).[30] The new name has led to confusion between omeprazole (Prilosec) and fluoxetine (Prozac), an antidepressant.[30]

AstraZeneca markets omeprazole as Losec, Antra, Gastroloc, Mopral, Omepral, and Prilosec. Omeprazole is marketed as Zegerid by Santarus, Prilosec OTC by Procter & Gamble and Zegerid OTC by Schering-Plough and as Segazole by Star Laboratories in Pakistan.[31][32] In the Philippines, Ajanta Pharma markets omeprazole under the brand name Zegacid. Dr. Reddy's Laboratories markets it as Omez in India, Russia, Romania, and South Africa. In Bangladesh Healthcare Pharmaceuticals Ltd. marketed omeprazole under the brand name Opal. In Bangladesh Apex Pharma also markets omeprazole under the brand name Aspra. It is also available under the brand name Rome 20 marketed by Rephco Pharmaceuticals Ltd. In Bangladesh the brand leader in this market is Seclo. In Argentina it is made by Bago Laboratories S.A. and available there and in Ecuador as Ulcozol. In Indonesia Darya-Varia Laboratories marketed omeprazole as Ozid. In Brazil, omeprazole is produced by Multilab under the name Lozeprel. In Spain it is produced by Cantabria Pharma S.L. under the name emeprotón. In Bangladesh, Eskayef Bangladesh Limited also marketed omeprazole under the brand name Losectil. The Acme Laboratories Limited marketed it under the brand name PPI.

In 1999, antiulcerants were the leading class of therapeutic drugs, with $15.6 billion in global sales. Of that, Prilosec accounted for $5.91 billion, making it the best-selling drug on the market.[33]

Although Prilosec's U.S. patent expired in April 2001, AstraZeneca was able to delay the introduction of generic versions through lawsuits and peripheral patent claims. It introduced Nexium as a patented replacement drug.[34]

Dosage forms

Omeprazole is available as tablets and capsules (containing omeprazole or omeprazole magnesium) in strengths of 10 mg, 20 mg, 40 mg, and in some markets 80 mg; and as a powder (omeprazole sodium) for intravenous injection. Most oral omeprazole preparations are enteric-coated, due to the rapid degradation of the drug in the acidic conditions of the stomach. This is most commonly achieved by formulating enteric-coated granules within capsules, enteric-coated tablets, and the multiple-unit pellet system (MUPS).

It is also available for use in injectable form (I.V.) in Europe, but not in the U.S. The injection pack is a combination pack consisting of a vial and a separate ampule of reconstituting solution. Each 10 ml clear glass vial contains a white to off-white lyophilised powder consisting of omeprazole sodium 42.6 mg equivalent to 40 mg of omeprazole.

Multiple unit pellet system

Omeprazole tablets manufactured by AstraZeneca (notably Losec/Prilosec) are formulated as a "Multiple Unit Pellet System" (MUPS). Essentially, the tablet consists of extremely small enteric-coated granules (pellets) of the omeprazole formulation inside an outer shell. When the tablet is immersed in an aqueous solution, as happens when the tablet reaches the stomach, water enters the tablet by osmosis. The contents swell from water absorption causing the shell to burst, releasing the enteric-coated granules. For most patients, the multiple-unit pellet system is of no advantage over conventional enteric-coated preparations. Patients for which the formulation is of benefit include those requiring nasogastric tube feeding and those with difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) because the tablets can be mixed with water ahead of time, releasing the granules into a slurry form, which is easier to pass down the feeding tube or to swallow than the pill.[citation needed] The granules are manufactured in a fluid air bed system. Sugar spheres in suspension are sequentially sprayed with aqueous suspensions of omeprazole, a protective layer, an enteric coating and an outer layer to reduce granule aggregation. The granules are mixed with other excipients and compressed into tablets. Finally, the tablets are film-coated to improve the stability and appearance of the preparation.

Immediate release formulation

In June 2004 the FDA approved an immediate release preparation of omeprazole and sodium bicarbonate that does not require an enteric coating. This preparation employs sodium bicarbonate as a buffer to protect omeprazole from gastric acid degradation. This allows for the production of chewable tablets. This combination preparation is marketed in the United States by Santarus under the brand name Zegerid. Zegerid is marketed as capsules, chewable tablets, and powder for oral suspension. Zegerid is most useful for those patients who suffer from nocturnal acid breakthrough (NAB) or those patients who desire immediate relief. In India it is marketed by Dr. Reddy's Laboratories as powder formulation with the brand name OMEZ-INSTA. It is reported to have additional benefits with patients suffering from alcoholic gastritis and life-style associated gastritis.

See also

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ Prilosec Prescribing Information. AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals.

- ^ Vaz-Da-Silva, M; Loureiro, AI; Nunes, T; Maia, J; Tavares, S; Falcão, A; Silveira, P; Almeida, L; Soares-Da-Silva, P (2005). "Bioavailability and bioequivalence of two enteric-coated formulations of omeprazole in fasting and fed conditions". Clin Drug Investig. 25 (6): 391–9. doi:10.2165/00044011-200525060-00004. PMID 17532679.

- ^ "What Causes Ulcers?". MedicineNet. 9 October 2009.

- ^ "Prilosec Side Effects & Drug Interactions". RxList.com. 2007. Retrieved 16 June 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Madanick RD (2011). "Proton pump inhibitor side effects and drug interactions: much ado about nothing?". Cleve Clin J Med. 78 (1): 39–49. doi:10.3949/ccjm.77a.10087. PMID 21199906.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Yang YX, Lewis JD, Epstein S, Metz DC (2006). "Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of hip fracture". JAMA. 296 (24): 2947–2953. doi:10.1001/jama.296.24.2947. PMID 17190895.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Targownik LE, Lix LM, Metge CJ, Prior HJ, Leung S, Leslie WD (2008). "Use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of osteoporosis-related fractures". CMAJ. 179 (4): 319–326. doi:10.1503/cmaj.071330. PMC 2492962. PMID 18695179.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Proton pump inhibitors and Clostridium difficile". Bandolier. 2003. Retrieved 13 July 2007.

- ^ Pali-Schöll I, Jensen-Jarolim E (2011). "Anti-acid medication as a risk factor for food allergy". Allergy. 66 (4): 469–77. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02511.x. PMID 21121928.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Herzig SJ, Howell MD, Ngo LH, Marcantonio ER (2009). "Acid-suppressive medication use and the risk for hospital-acquired pneumonia". JAMA. 301 (20): 2120–2128. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.722. PMID 19470989.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tubulointerstitial Nephritis at The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Professional Edition

- ^ Ray S, Delaney M, Muller AF (2010). "Proton pump inhibitors and acute interstitial nephritis". BMJ. 341: c4412–c4412. doi:10.1136/bmj.c4412. PMID 20861097.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thomson AB, Sauve MD, Kassam N, Kamitakahara H (2010). "Safety of the long-term use of proton pump inhibitors". World J Gastroenterol. 16 (19): 2323–30. doi:10.3748/wjg.v16.i19.2323. PMC 2874135. PMID 20480516.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ http://www.drugs.com/pro/prilosec.html Drugs.com - "Prilosec"

- ^ a b Stedman CA, Barclay ML (2000). "Review article: comparison of the pharmacokinetics, acid suppression and efficacy of proton pump inhibitors". Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 14 (8): 963–978. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00788.x. PMID 10930890.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lau WC, Gurbel PA (2009). "The drug-drug interaction between proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel". CMAJ. 180 (7): 699–700. doi:10.1503/cmaj.090251. PMC 2659824. PMID 19332744.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Norgard NB, Mathews KD, Wall GC (2009). "Drug-drug interaction between clopidogrel and the proton pump inhibitors". Ann Pharmacother. 43 (7): 1266–1274. doi:10.1345/aph.1M051. PMID 19470853.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pauli-Magnus C, Rekersbrink S, Klotz U, Fromm MF (2001). "Interaction of omeprazole, lansoprazole and pantoprazole with P-glycoprotein". Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 364 (6): 551–557. doi:10.1007/s00210-001-0489-7. PMID 11770010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Izzo, AA; Ernst, E (2009). "Interactions between herbal medicines and prescribed drugs: an updated systematic review". Drugs. 69 (13): 1777–1798. doi:10.2165/11317010-000000000-00000. PMID 19719333.

- ^ http://www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB00338#pharmacology

- ^ "Omeprazole, in The Free Medical Dictionary". Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ "Omeprazole". Drugs.com. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ "Zegird, How to take". rxlist.com. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ essential drug information. MIMS USA. Retrieved 20 December 2009.[verification needed]

- ^ Cass, QB; Lima, VV; Oliveira, RV; Cassiano, NM; Degani, AL; Pedrazzoli, J (2003). "Enantiomeric determination of the plasma levels of omeprazole by direct plasma injection using high-performance liquid chromatography with achiral-chiral column-switching". Journal of Chromatography B. 798 (2): 275–281. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2003.09.053. PMID 14643507.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Baselt RC, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 1146–7. ISBN 978-0-9626523-7-0.

- ^ Nexium Prescribing Information. AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals.

- ^ Furuta T, Shirai N, Sugimoto M, Nakamura A, Hishida A, Ishizaki T (2005). "Influence of CYP2C19 pharmacogenetic polymorphism on proton pump inhibitor-based therapies". Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 20 (3): 153–67. doi:10.2133/dmpk.20.153. PMID 15988117.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Farley, D (1995). "Making it easier to read prescriptions". FDA Consum. 29 (6): 25–7. PMID 10143448.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Santarus Receives FDA Approval for Immediate-Release Omeprazole Tablet with Dual Buffers". Santarus.

- ^ "FDA Approves Zegerid OTC for Over-the-Counter Treatment of Frequent Heartburn". Merck.

- ^ Lisa Jarvis (18 September 2000). "AstraZeneca Introduces Next Generation Prilosec". ICB Americas/icis.com.

- ^ Gardiner Harris (6 June 2002). "Prilosec's Maker Switches Users To Nexium, Thwarting Generics". The Wall Street Journal.

External links