Miami Seaquarium

| Miami Seaquarium | |

|---|---|

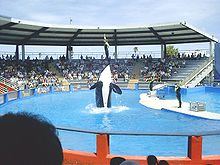

The killer whale show at Miami Seaquarium, starring Lolita, a 7,000 pounds (3,200 kg) Southern killer whale | |

| |

| 25°43′59″N 80°09′56″W / 25.733°N 80.165525°W | |

| Date opened | September 24, 1955 [1] |

| Location | Virginia Key, Miami, Florida, US |

| Land area | 38 acres (15 ha) |

| Annual visitors | 500,000 |

| Memberships | Alliance of Marine Mammal Parks and Aquariums AMMPA |

| Owner | The Dolphin Company[2] |

| Website | miamiseaquarium |

| |

The Miami Seaquarium is a 38-acre (15 ha) oceanarium located on the island of Virginia Key in Biscayne Bay, Miami-Dade County, Florida located near downtown Miami.

Founded in 1955, it is one of the oldest oceanariums in the United States. In addition to marine mammals, the Miami Seaquarium houses fish, sharks, sea turtles, birds, reptiles, and manatees. The park offers daily presentations and hosts overnight camps, events for boy scouts, and group programs. Over 500,000 people visit the facility annually. The park has around 225 employees, and its lease payments and taxes make it the third-largest contributor to Miami-Dade County's revenue.[1]

History

The park was founded by Fred D. Coppock and Captain W.B. Gray and was the second marine-life attraction in Florida. When it opened in 1955, it was the largest marine-life attraction in the world.[1]

The park's first orca was Hugo, named after Hugo Vihlen.[3] Hugo was captured in February 1968 in Vaughn Bay. Shortly after his capture, Hugo was flown to the Miami Seaquarium where he was held in a small pool for two years. Over the course of 10 years, judging by his behavior, it was clear that Hugo didn't adjust to his life in captivity. Hugo would regularly bang his head against the walls of the tank. On March 4, 1980, Hugo died of a brain aneurysm.[4]

From 1963 through 1967, eighty-eight episodes of the 1960s TV show Flipper and two movies starring Flipper were filmed at the Miami Seaquarium. From 1963 to 1991, the Seaquarium also had the Miami Seaquarium Spacerail, which was the first hanging monorail in the United States.

In 2014 Miami Seaquarium was bought by Palace Entertainment.[5][6]

Lolita the Killer Whale

One of the Miami Seaquarium's attractions is Lolita, the second oldest orca in captivity behind Corky at SeaWorld San Diego. She is currently the park's only orca. Lolita arrived at the Miami Seaquarium in 1970, where she joined the park's first orca, Hugo. Hugo died in 1980 after injuring himself along the walls of the tank where Lolita still swims.[7] Animal rights activists have long argued that the tank doesn't meet federal minimum requirements under the Animal Welfare Act, and the USDA has recently made statements in support of the activists' argument.[8]

On January 24, 2014 the National Marine Fisheries Service proposed amending the Endangered Species Act to remove the exception that did not include Lolita as part of the ESA-listed Southern Resident population of orcas that live in Washington and British Columbia waters. Activists, who proposed such an action to the NMFS in 2013, are hopeful that this might lead to a healthy retirement in a seapen and possibly an eventual release and reuniting with her pod which is believed by some to include her mother.

The Lummi Nation of Washington State refer to Lolita as Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut, or, a female orca from an ancestral site in the Penn Cove area of the Salish Sea bioregion.[9] They view her as a member of their "qwe lhol mechen," which "'translates to ‘our relative under the water,’” according to former Lummi tribal chairman Jay Julius. She is a viewed as a member of the Lummi Nation's family, and they believe that she should be returned to the Salish Sea bioregion. The Lummi have gathered at Seaquarium numerous times to ask that Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut be returned.[10][11] In 2018 Seaquarium Curator Emeritus Robert Rose responded to Lummi protests, saying that the Lummi "should be ashamed of themselves, they don’t care about Lolita, they don’t care about her best interests, they don’t really care whether she lives or dies. To them, she is nothing more than a vehicle by which they promote their name, their political agenda, to obtain money and to gain media attention. Shame on them."[12] In response, environmental scholars and Julius have argued that such statements are representative of a troubling pattern of discounting Native American knowledge and relationships which are "part and parcel of the possessive nature of settler colonialism."[9]

Gallery

-

Lolita, the Killer Whale.

-

The Top Deck dolphin show at the Miami Seaquarium.

-

Dolphin named Bebe at the Seaquarium in 1969.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c "About Us: History". Archived from the original on March 6, 2013. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- ^ "Miami Seaquarium Being Sold". August 18, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ^ "Miami Seaquarium - About Miami Seaquarium". Miami Seaquarium. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ "One Dolphin's Story – Hugo". Dolphin Project. August 3, 2015. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ "Miami Seaquarium deal is done". The Real Deal. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- ^ "List of parks". Palace Entertainment. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- ^ "Livid Over Lolita's Continued Captivity, Celebrities Call for Boycott of Miami Seaquarium". Miami New Times. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ^ "USDA Officials Say Lolita's Tank at Miami Seaquarium Might Violate Federal Law". Miami New Times. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ^ a b Guernsey, Paul J.; Keeler, Kyle; Julius, Jeremiah ‘Jay’ (July 30, 2021). "How the Lummi Nation Revealed the Limits of Species and Habitats as Conservation Values in the Endangered Species Act: Healing as Indigenous Conservation". Ethics, Policy & Environment: 1–17. doi:10.1080/21550085.2021.1955605. ISSN 2155-0085.

- ^ Mapes, Lynda (2018). "Lummi prayers, songs, at Seaquarium just start of effort to free captive whale". Seattle Times.

- ^ Priest, Rena (2020). "A captive orca and a chance for our redemption". High Country News.

- ^ Rose, Robert (2018). "Lolita Update From Our Curator Emeritus, Robert Rose". Facebook.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)