Haymarket affair

41°53′06″N 87°38′39″W / 41.8849°N 87.6441°W

Haymarket Martyrs' Monument | |

Marker placed in 1997 | |

| Location | Forest Park, Illinois |

|---|---|

| Built | 1887 |

| Architect | Weinert, Albert |

| NRHP reference No. | 97000343 [1] |

| Added to NRHP | February 18, 1997 |

The Haymarket Riot on May 4, 1886 in Chicago is generally considered to have been an important influence on the origin of international May Day observances for workers. [2] In popular literature this event inspired the caricature of "a bomb-throwing anarchist." The causes of the incident are still controversial, although deeply polarized attitudes separating the business class and the working class in late 19th century Chicago are generally acknowledged as having precipitated the tragedy and its aftermath.

Strife and confrontation

May Day parade and strikes

On May 1 1886, labor unions organized a strike for an eight-hour work day in Chicago. Albert Parsons, head of the Chicago Knights of Labor, with his wife Lucy Parsons and seven children, led 80,000 people down Michigan Avenue in what is widely cited as the first May Day Parade. In the next few days they were joined nationwide by 350,000 workers, including 70,000 in Chicago, who went on strike at 1,200 factories.

On May 3 striking workers met near the McCormick Harvesting Machine Co. plant where a fight broke out on the picket lines as replacement workers attempted to cross the picket line. Chicago police intervened and attacked the strikers, killing four, wounding several others and sparking outrage in the city's working community.

Local anarchists distributed fliers calling for a rally at Haymarket Square, then a bustling commercial center (also called the Haymarket) near the corner of Randolph Street and Des Plaines Street in what was later called Chicago's west Loop. These fliers alleged police had murdered the strikers on behalf of business interests and urged workers to seek justice. In response to the McCormick killings, prominent anarchist August Spies published "Revenge! Workingmen to Arms!" This pamphlet urged workers to take action:

- To arms we call you, to arms!

Rally at Haymarket Square

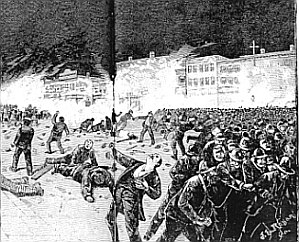

The rally began peacefully under a light rain on the evening of May 4. August Spies spoke to the large crowd while standing in an open wagon on Desplaines Street[3]. According to many witnesses Spies said he was not there to incite anyone. Meanwhile a large number of on-duty police officers watched from nearby. The crowd was so calm that Mayor Carter Harrison, Sr., who had stopped by to watch, walked home early. Some time later the police ordered the rally to disperse and began marching in formation towards the speakers' wagon. A bomb was thrown at the police line and exploded, killing policeman Mathias J. Degan.[4] Seven other policemen later died from their injuries. The police immediately opened fire on the crowd, injuring dozens. Many of the wounded were afraid to visit hospitals for fear of being arrested. A total of eleven people died.

Trial, executions and pardons

Eight people connected directly or indirectly with the rally and its anarchist organisers were charged with Degan's murder: August Spies, Albert Parsons, Adolph Fischer, George Engel, Louis Lingg, Michael Schwab, Samuel Fielden and Oscar Neebe. Five (Spies, Fischer, Engel, Lingg and Schwab) were German immigrants while a sixth, Neebe, was a U.S. citizen of German descent.

The trial was presided over by Judge Joseph Gary. The defense counsel included Sigmund Zeisler,William Perkins Black, William Foster, and Moses Salomon. The prosecution, led by Julius Grinnell, did not offer evidence connecting any of the defendants with the bombing, but argued that the person who had thrown the bomb had been encouraged to do so by the defendants, who as conspirators were equally responsible.

The jury returned guilty verdicts for all eight defendants, with death sentences for seven. Neebe received a sentence of 15 years in prison. The sentencing sparked outrage from budding labor and workers movements, resulted in protests around the world, and made the defendants international political celebrities and heroes within labor and radical political circles. Meanwhile, the press published often sensationalized accounts and opinions about the incident, which polarized public reaction. Journalist George Frederic Parsons, for example, wrote a piece for the Atlantic Monthly articulating the fears of middle-class Americans concerning labor radicalism, asserting that workers had only themselves to blame for their troubles.[5]

The case was appealed to the Supreme Court of Illinois, [6] then to the Supreme Court of the United States, where the defendants were represented by John Randolph Tucker, Roger Atkinson Pryor, General Benjamin F. Butler and William P. Black. The petition for certiorari was denied.[7]

After the appeals had been exhausted, Illinois Governor Richard James Oglesby commuted Fielden's and Schwab's sentences to life in prison. On the eve of his scheduled execution, Lingg committed suicide in his cell using a smuggled dynamite cap which he reportedly held in his mouth like a cigar (the blast blew off half his face and he survived in agony for several hours).

The next day, November 11 1887, Spies, Parsons, Fischer, and Engel were hanged together before a public audience. Taken to the gallows in white robes and hoods, they sang the Marseillaise, the anthem of the international revolutionary movement. Family members including Lucy Parsons who attempted to see them for the last time were arrested and searched for bombs. None were found. August Spies was widely quoted as having shouted out, "The time will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today." Witnesses reported that the condemned did not die when they dropped, but strangled to death slowly, a sight which left the audience visibly shaken.[citation needed]

Lingg, Spies, Fischer, Engel and Parsons were buried at the German Waldheim Cemetery in Forest Park, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. Schwab and Neebe where also buried at Waldheim when they died, reuniting the "Martyrs." In 1893 the Haymarket Martyrs Monument by sculptor Albert Weinert was raised at Waldheim. Over a century later it was designated a National Historic Landmark by the United States Department of the Interior, the only cemetery memorial to be noted as such.

The trial is often referred to by scholars as one of the most serious miscarriages of justice in United States history.[8] On June 26 1893, Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld signed pardons for Fielden, Neebe, and Schwab after having concluded all eight defendants were innocent. The pardons ended his political career.

The police commander who ordered the dispersal was later convicted of corruption. The bomb thrower was never identified, although some anarchists privately indicated they had later learned his identity but kept quiet to avoid further prosecutions.[citation needed]

Haymarket Square in the aftermath

In 1889 a commemorative nine-foot bronze statue of a Chicago policeman by sculptor Johannes Gelert was erected in the middle of Haymarket Square with private funds raised by the Union League Club of Chicago. On the 41st anniversary of the riot, May 4 1927, a streetcar jumped its tracks and crashed into the monument (statements made by the driver suggested this may have been deliberate).

The city moved it to nearby Lincoln Park. During the early 1960s, freeway construction erased about half of the old, run down market square and the statue was moved back to a spot on a newly built outcropping overlooking the freeway, near its original location. In October 1969 it was blown up, repaired by the city and blown up again a year later, reportedly by the Weather Underground.

Mayor Richard J. Daley placed a 24-hour police guard around the statue for two years before it was moved to the enclosed courtyard of Chicago Police academy in 1972. The statue's empty, graffiti-marked pedestal stood in the desolate remains of Haymarket Square for another three decades, where it was known as an anarchist landmark.

In 1985, scholars doing research for a possible centennial commemoration of the riot were surprised to learn that most of the primary source documentation relating to the incident was not in Chicago, but had been transferred to then-communist East Berlin.

In 1992 the site of the speakers' wagon was marked by a bronze plaque set into the sidewalk, reading:

A decade of strife between labor and industry culminated here in a confrontation that resulted in the tragic death of both workers and policemen. On May 4 1886, spectators at a labor rally had gathered around the mouth of Crane's Alley. A contingent of police approaching on Des Plaines Street were met by a bomb thrown from just south of the alley. The resultant trial of eight activists gained worldwide attention for the labor movement, and initiated the tradition of "May Day" labor rallies in many cities.

- Designated on March 25, 1992

- Richard M. Daley, Mayor

On September 14 2004, after 118 years of what some observers called civic amnesia, Daley and union leaders unveiled a monument by Chicago artist Mary Brogger, a fifteen-foot speakers' wagon sculpture echoing the wagon on which the labor leaders stood in Haymarket Square to champion the eight-hour day. The bronze sculpture, centerpiece of a proposed "Labor Park" there, is meant to symbolize both the assembly at Haymarket and free speech. The planned site was to include an international commemoration wall, sidewalk plaques, a cultural pylon, seating area and banners but a year later work had not yet begun.

Defendants

- August Spies, German immigrant, was hanged

- Albert Parsons, U.S. citizen, was hanged

- Adolph Fischer, German immigrant, was hanged

- George Engel, German immigrant, was hanged

- Louis Lingg, German immigrant, sentenced to death, took his own life with dynamite while in prison

- Michael Schwab, German immigrant, death sentence commuted to life in prison, then pardoned in 1893

- Samuel Fielden, English immigrant, death sentence commuted to life in prison, then pardoned in 1893

- Oscar Neebe, U.S. citizen of German descent, sentenced to 15 years, served seven until pardoned in 1893

See also

Notes

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2006-03-15.

- ^ "The History of May Day" (in socialism), Alexander Trachtenberg, International Pamphlets (1932), March 2002, Marxists.org webpage: Marxists-MayDay

- ^ 163 North Desplaines Street

- ^ Officer Down Memorial Page, Inc.

- ^ George Frederic Parsons, "The Labor Question," Atlantic Monthly, v.58, pp. 97-113 (July 1886).

- ^ 122 Ill. 1

- ^ 123 U.S. 131.

- ^ Dave Roediger, Haymarket Incident

References

- The Autobiographies of the Haymarket Martyrs, Pathfinder Press, New York, ISBN 0-87348-879-2.[1]

- Avrich, Paul, The Haymarket Affair.

- Bach, Ira and Mary Lackritz Gray, Chicago's Public Sculpture, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, 1983.

- Fireside, Bryna J, Haymarket Square Riot Trial: A Headline Court Case, Enslow Publishers, Inc., Berkeley Heights, NJ, 2002.

- Green, James, Death in the Haymarket, Pantheon, 2006.

- Harris, Frank, The Bomb, Feral House Printing, Portland, OR, 1963.

- Hucke, Matt and Ursula Bielski, Graveyards of Chicago, Lake Claremont Press, Chicago, IL, 1999.

- Kvaran, Einar Einarsson, Haymarket - A Century Later, unpublished manuscript.

- Riedy, James L, Chicago Sculpture, University of Illinois Press, Urbana, IL, 1981.

- Rodeiger, Dave and Rosemont, Franklin, ed. Haymarket Scrapbook, Charles H. Kerr Publishing Co., Chicago, 1986.

- Michael J. Schaack (1889). Anarchy and anarchists: a history of the red terror and the social revolution in America and Europe : communism, socialism, and nihilism in doctrine and in deed : the Chicago Haymarket conspiracy, and the detection and trial of the conspirators. Chicago: F.J. Schulte & Co..

External links

- The Haymarket Martyrs

- The Haymarket Monument

- The Haymarket Affair Digital Archive

- The Haymarket Massacre Archive

- Mayday and the Haymarket Martyrs

- The Haymarket Massacre Anarchy Now! page

- Officer Down Memorial Page

- Library of Congress Memory page

- Death in the Haymarket:A Story of Chicago, the First Labor Movement, and the Bombing that Divided Gilded-Age America

- Ripley's Believe It or Not! purchases Cook County gallows used to execute Spies, Parsons, Fischer, and Engel for $68,300 [2]

External images

- Registered Historic Places in Cook County, Illinois

- History of anarchism

- History of socialism

- History of social movements

- History of Chicago

- History of anti-communism in the United States

- History of labor relations in the United States

- Riots and civil unrest in the United States

- Communism

- History of the United States (1865–1918)

- Labor disputes in the United States