Greek junta

The Greek military junta of 1967-1974, alternatively "The Regime of the Colonels" (Greek: Το καθεστώς των Συνταγματαρχών), or in Greece "The Junta" (Greek: Η Χούντα) is a collective term used to refer to a series of right-wing military governments that ruled Greece from 1967 to 1974.

The rule by the military started in the morning of 21 April 1967 with a coup d'état led by a group of colonels of the military of Greece, and ended in July, 1974.

History of the Junta

| History of Greece |

|---|

|

|

|

Background

The 1967 coup and the following seven years of military rule were the epitome of 30 years of national division between the forces of the Left and the Right that can be traced to the time of the resistance against Axis occupation of Greece during World War Two. After the liberation in 1944 Greece descended into civil war, fought between the forces of the Communist-led Greek resistance and the now returned government-in-exile.

American influence in Greece

In 1947, the United States formulated the Truman Doctrine, and began to actively support a series of authoritarian governments in Greece, Turkey and Iran, in order to ensure that these states did not fall under Soviet influence. With American and British aid, the civil war ended with the military defeat of the Left in 1949. The Communist Party of Greece (KKE) was outlawed and many Communists had to either flee the country or face persecution. The CIA and the Greek military began to work closely, especially after Greece joined NATO in 1952. Greece was a vital link in the NATO defense arc which extended from the eastern border of Iran to the northmost point in Norway. Greece in particular was seen as being in risk, having experienced a Communist insurgency. In particular, the newly-founded Hellenic National Intelligence Service (KYP) and the LOK Special Forces (later actively involved in the 1967 coup) maintained a very close liaison with their American counterparts. In addition to preparing for a Soviet invasion, they agreed to guard against a leftist coup. The LOK in particular were integrated into the Gladio European stay-behind network.[citation needed]

The Apostasia and Political Instability

After many years of conservative rule, the election of centrist George Papandreou, Sr. as Prime Minister was a sign of change. In a bid to gain more control over the country's government than what his limited constitutional powers allowed, the young and inexperienced King Constantine II clashed with liberal reformers, dismissing Papandreou in 1965, causing a constitutional crisis known as the Apostasia of 1965.

After making several attempts to form governments, relying on dissident Center Union and conservative MPs, Constantine II appointed an interim government under Ioannis Paraskevopoulos, and new elections were called for 28 May 1967. There were many indications that Papandreou's Center Union would emerge as the largest party, but would not be able to form a single-party government and would be forced into an alliance with the United Democratic Left, which was suspected by conservatives of being a proxy for the banned Communist Party of Greece. This possibility was used as a pretext for the coup.

A "Generals' Coup"

Greek historiography and the press have also hypothesized about a "Generals' Coup",[1], a coup that would have been deployed at the behest of the palace,[2] under the pretext of combatting communist subversion.[3]

A number of National Radical Union politicians feared that the policies of leftist members of the Center Union, such as Andreas Papandreou and Spyros Katsotas, would lead to a constitutional crisis. One such politician, George Rallis, has recounted he had proposed that, in case of such an "anomaly", the King should declare martial law, as the monarchist constitution permitted him. According to Rallis, Constantine was receptive to the idea.[4].

In 1966 Constantine II of Greece sent his envoy Demetrios Bitsios to Paris on mission to convince Constantine Karamanlis to return to Greece and resume a role in Greek politics. According to uncorroborated claims made by the former monarch, in 2006 and after the deaths of the two men involved, Karamanlis replied to Bitsios that he would only return if the King imposed martial law, as was his constitutional prerogative.[5]

US journalist Cyrus L. Sulzberger has separately claimed that Karamanlis flew to New York to lobby US support from Lauris Norstad for a coup d'état in Greece that would establish a strong conservative regime under himself; Sulzberger alleges that Norstad declined to involve himself in such affairs.[3] Sulzberger's account, which unlike that of the former King was delivered during the lifetime of those implicated (Karamanlis and Norstad), rested solely on the authority of his and Norstad's word. When, in 1997, the former King reiterated Sulzberger's allegations, Karamanlis stated that he "will not deal with the former king's statements because both their content and attitude are unworthy of comment". [6] The deposed King's adoption of Sulzberger's claims against Karamanlis was castigated by the left-leaning media, typically critical of Karamanlis, as "shameless" and "brazen".[6] It bears noting that, at the time, the former King referred exclusively to Sulzberger's account, to support the theory of a planned coup by Karamanlis, and made no mention of the alleged 1966 meeting with Bitsios, which he would refer to only after both participants had died and could not respond.

As it turned out, the constitutional crisis did not originate either from the political parties, or from the Palace, but from middle-rank army putschists.

The coup d'état of 21 April

On 21 April, 1967, (just weeks before the scheduled elections), a group of right-wing army officers led by Brigadier Stylianos Pattakos and Colonels George Papadopoulos and Nikolaos Makarezos seized power in a coup d'etat. The colonels were able to quickly seize power by using surprise and confusion. Pattakos was commander of the Armour Training Centre (Greek: Κέντρο Εκπαίδευσης Τεθωρακισμένων ΚΕΤΘ/Kentro Ekpaideusis Tethorakismenon KETTH), based in Athens. The coup leaders placed tanks in strategic positions in Athens, effectively gaining complete control of the city. At the same time, a large number of small mobile units were dispatched to arrest leading politicians and authority figures, as well as many ordinary citizens suspected of left-wing sympathies. One of the first to be arrested was Lieutenant General George Spantidakis, Commander-in-Chief of the Greek Army.

The conspirators were known to Spantidakis. Indeed, he was instrumental in bringing some of them to Athens, to use in a coup he and other leading Army generals had been planning, in an attempt to prevent George Papandreou's victory in the upcoming election and the Communist takeover that would, supposedly, follow it. The colonels succeeded in persuading Spantidakis to join them and he issued orders activating an action plan (the "Prometheus" plan) that had been previously drafted as a response for a hypothetical Communist uprising (see Operation Gladio). Under the command of paratrooper Lieutenant Colonel Costas Aslanides, the LOK (see above) took control of the Greek Defence Ministry while Brigadier General Stylianos Pattakos gained control over communication centers, the parliament, the royal palace, and according to detailed lists, arrested over 10,000 people. Since orders came from a legal source, commanders and units not involved in the conspiracy automatically obeyed them. Many of the arrested were held during the first days in the "Ippodromos" (a stadium for horse racing by the sea) and some of them (Panayotis Elis one of them) were executed in cold blood by young army officers.

By the early morning hours the whole of Greece was in the hands of the colonels. All leading politicians, including acting Prime Minister Panagiotis Kanellopoulos, had been arrested and were held incommunicado by the conspirators. Phillips Talbot, the US ambassador in Athens, disapproved of the military coup, complaining that it represented "A rape of democracy", to which Jack Maury, the CIA chief of station in Athens, answered, "How can you rape a whore?"[7] The Papadopoulos' junta attempted to re-engineer the Greek political landscape by coup.

The role of the King

When the tanks rolled on to Athens streets on 21 April, the legitimate National Radical Union government, of which Rallis was a member, asked King Constantine to immediately mobilise the state against the coup; he declined to do so, and swore in the dictators as the legitimate government of Greece, while asserting that he was "certain they had acted in order to save the country".

The three plot leaders visited Constantine in his residence in Tatoi, which they circled with tanks, effectively preventing any form of resistance. The King wrangled with the colonels and initially dismissed them, ordering them to return with Spantidakis. Later in the day he took it upon himself to go the Ministry of National Defence, located north of Athens city centre, where all the coup leaders were gathered. The King had a discussion with Kanellopoulos, who was detained there, and with leading generals. This was a pointless exercise, since Kanellopoulos was a prisoner whilst the generals had no real power, as was evident from the shouting of lower and middle-ranking officers, refusing to obey orders and clamouring for a new government under Spantidakis.[citation needed] The King finally relented and decided to co-operate, claiming to this day that he was isolated and did not know what else to do.

He has since claimed that he was trying to gain time to organise a counter-coup and oust the Junta. He did organise such a counter-coup; however, the fact that the new government had a legal origin, in that it had been appointed by the legitimate head of state, played an important role in the coup's success. The King was later to regret bitterly his decision. For many Greeks, it served to identify him indelibly with the coup and certainly played an important role in the final decision to abolish the monarchy, sanctioned by the 1974 referendum.

The only concession the King could achieve was to appoint a civilian as prime minister, rather than Spantidakis. Konstantinos Kollias, a former Attorney General of the Areios Pagos, was chosen. He was a well-known royalist and had even been disciplined under the Papandreou government for meddling in the investigation on the murder of MP Gregoris Lambrakis. Kollias was little more than a figurehead and real power rested with the army, and especially Papadopoulos, who emerged as the coup's strong man and became Minister of Defence and Minister of the Government's Presidency. Other coup members occupied key posts. Up until then constitutional legitimacy had been prevented, since under the then-Greek Constitution the King could appoint whomever he wanted as prime minister, as long as Parliament endorsed the appointment with a vote of confidence or a general election was called.

It was this government, sworn-in in the early evening hours of 21 April, that formalised the coup. It adopted a "Constituent Act", an amendment tantamount to a revolution, cancelling the elections and effectively abolishing the constitution, which would be replaced later. In the meantime, the government was to rule by decree. Since traditionally such Constituent Acts did not need to be signed by the Crown, the King never signed it, permitting him to claim, years later, that he had never signed any document instituting the junta. Critics claim that Constantine II did nothing to prevent the government (and especially his chosen prime minster Kollias) from legally instituting the authoritarian government to come.

This same government formally published and enforced a decree, already proclaimed on radio as the coup was in progress, instituting military law. Constantine claimed he never signed that decree either.

The King's Counter-Coup

From the outset, the relationship between King Constantine II and the Colonels was an uneasy one. The colonels were not willing to share power with anyone, whereas the young King, like his father before him, was used to playing an active role in politics and would never consent to being a mere figurehead, especially in a military administration. Although the colonels' strong anti-communist, pro-NATO and pro-Western views appealed to the United States, fearful of domestic and international public opinion, President of the United States Lyndon B. Johnson told Constantine, in a visit to Washington, D.C. in early autumn of 1967, that it would be best to replace that government with another one.[citation needed] Constantine took that as an encouragement to organise a counter-coup and it was probably meant as one, although no direct help or involvement of the US was forthcoming.

The King finally decided to launch his counter-coup on 13 December 1967. Since Athens was effectively in the hands of the junta militarily, Constantine decided to fly to the small northern city of Kavala. There he hoped to be among troops loyal only to him. The vague plan he and his advisors had conceived was to form a unit that would advance on and take Thessaloniki. Constantine planned to install an alternative administration there. International recognition, which he believed to be forthcoming, as well as internal pressure from the fact that Greece would have been split in two governments would, the King hoped, force the junta to resign, leaving the field clear for him to return triumphant to Athens.

In the early morning hours of 13 December, the King boarded the royal plane, together with Queen Anne-Marie of Greece, their two baby children Princess Alexia of Greece and Denmark and Pavlos, Crown Prince of Greece, his mother Frederika of Hanover and his sister, Princess Irene of Greece and Denmark. Constantine also took with him Prime Minister Kollias. At first, things seemed to be going according to plan. Constantine was well received in Kavala which, militarily, was under the command of a general loyal to him. The Air Force and Navy, both strongly royalist and not involved in the 1967 coup, immediately declared for him and mobilised. Another of Constantine's generals effectively cut all communication between Athens and northern Greece.

However, the King's plans were overly bureaucratic, naïvely supposing that orders from a commanding general would automatically be obeyed. Further, the King was obsessive about avoiding "bloodshed", even where the junta would be the attacker. Instead of attempting to drum up the widest popular support, hoping for spontaneous pro-democracy risings in most towns, the King preferred to let his generals put together the necessary force for advancing on Thessaloniki in strict compliance with military bureaucracy.[citation needed] The King made no attempt to contact politicians, even local ones, and even took care to include in his proclamation a paragraph condemning communism, lest anyone should get the wrong idea.

In the circumstances, rather than the King managing to put together a force and advancing on Thessaloniki, middle-ranking pro-junta officers neutralised and arrested his royalist generals and took command of their units, which subsequently put together a force to advance on Kavala to arrest the King. The junta, not at all shaken by the loss of their figurehead premier, ridiculed the King by announcing the he was hiding "from village to village". Realising that the counter coup had failed, Constantine fled Greece on board the royal plane, taking his family and hapless Prime Minister with him. They landed in Rome early in the morning of 14 December. Constantine remained in exile all through the rest of military rule (although nominally he continued as King until 1 June 1973, and was never to return to Greece as King.

The Regency

The flight of the King and Prime Minister to Italy left Greece with no legal government or head of state. This did not concern the military junta. Instead the Revolutionary Council, composed of Pattakos, Papadopoulos and Makarezos, issued a notice in the Government Gazette appointing another member to the military administration, Major General Georgios Zoitakis, as Regent. Zoitakis then appointed Papadopoulos Prime Minister. This became the only government of Greece after the failure of the King's attempted coup, as the King was unwilling to set up an alternative administration in exile. The Regent's position was later confirmed under the 1968 Constitution, although the exiled King never officially recognised, or acknowledged, the Regency.

In a legally controversial move, even under the junta's own Constitution, the Cabinet voted on 21 March 1972 to oust Zoitakis and replace him with Papadopoulos, thus combining the offices of Regent and Prime Minister. It was thought Zoitakis was problematic and interfered too much with the military. The King's portrait remained on coins, in public buildings, etc., but slowly, the military was chipping away at the institution of the monarchy: the royal family's tax immunity was abolished, the complex network of royally managed charities was brought under direct state control, the royal arms were removed from coins, the Navy and Air Force were no longer "Royal" and the newspapers were usually banned from publishing the King's photo or any interviews.

During this period, resistance against the colonels' rule became better organized among exiles in Europe and the United States. In addition to the expected opposition from the left, the colonels found themselves under attack by constituencies that had traditionally supported past right-wing regimes: pro-monarchists supporting Constantine; businessmen concerned over international isolation; the middle class facing an economic downturn after 1971.[citation needed] There was also considerable political infighting within the junta. Still, up until 1973 the junta appeared in firm control of Greece, and not likely to be ousted by violent means.

Normalization and attempts at liberalization

Papadopoulos had indicated as early as 1968 that he was eager for a reform process and even tried to contact Markezinis at the time. He had declared at the time that he did not want the "Revolution", (junta speak for the "dictatorship"), to become a "regime". He then repeatedly attempted to initiate reforms in 1969 and 1970, only to be thwarted by the hardliners including Ioannides. In fact subsequent to his 1970 failed attempt at reform, he threatened to resign and was dissuaded only after the hardliners renewed their personal allegiance to him.[8]

As internal dissatisfaction grew in the early 1970s, and especially after an abortive coup by the Navy in early 1973,[8] Papadopoulos attempted to legitimize the regime by beginning a gradual "democratization" (See also the article on Metapolitefsi). On 1 June 1973, he abolished the monarchy and declared himself President of the Republic after a controversial referendum, the results of which were not recognised by the political parties. He furthermore sought the support of the old political establishment, but secured only the cooperation of Spiros Markezinis, who became Prime Minister. Concurrently, many restrictions were lifted, and the army's role significantly reduced. Papadopoulos intended to establish a presidential republic, with extensive powers vested in the office of President, which he held. The decision to return to political rule and the restriction of their role was resented by many of the regime's supporters in the Army, whose dissatisfaction with Papadopoulos would become evident a few months later.

Collapse

The Ioannidis Regime

On 25 November 1973, following the bloody suppression of the Athens Polytechnic uprising on November 17, General Dimitrios Ioannides ousted Papadopoulos and tried to continue to rule despite the popular unrest the uprising had triggered.

Sponsorted by Ioannides, on 15 July, 1974 the EOKA-B organisation took power on the island of Cyprus by a military coup, in which Archbishop Makarios III, the Cypriot president, was overthrown. Turkey replied to this intervention five days later with its own, and invaded Cyprus, occupying part of the island. There was a well founded fear that an all out war with Turkey was imminent. This brought Greece to the brink of war with Turkey.

While the collapse of the junta was immediately triggered by the Cyprus debacle, some argue that the 1973 Athens Polytechnic uprising was the event that discredited the military government most and acted as a key catalyst for its eventual collapse.

Restoration of Democracy

The Cyprus fiasco led to senior Greek military officers withdrawing their support for Junta strongman Brigadier Dimitrios Ioannides. Junta-appointed President Phaedon Gizikis called a meeting of old politicians, including Panagiotis Kanellopoulos, Spiros Markezinis, Stephanos Stephanopoulos, Evangelos Averoff, and others. The agenda was to appoint a national unity government that would lead to country to elections. Although former Prime Minister Panagiotis Kanellopoulos was originally backed, Gizikis finally invited former Prime Minister Constantine Karamanlis, who had resided in Paris since 1963, to assume the role. Karamanlis returned to Athens on a French Presidency Lear Jet made available to him by President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, a close personal friend, and was sworn-in as Prime Minister under President Phaedon Gizikis. Karamanlis' new party, New Democracy, won the November 1974 general election, and he remained prime minister.

Characteristics of the Junta

Ideology

The colonels preferred to call the coup d'état of 21 April a "revolution to save the nation" ("Ethnosotirios Epanastasis"). Their official justification for the coup was that a "communist conspiracy" had infiltrated the bureaucracy, academia, the press, and even the military, to such an extent that drastic action was needed to protect the country from communist takeover. Thus, the defining characteristic of the Junta was its staunch anti-Communism. They used the term anarcho-communist (Greek: αναρχοκομμουνιστές, anarchokommounistes) to describe all leftists. In a similar vein the junta attempted to steer Greek public opinion not only by propaganda but also by inventing new words and slogans, such as old-partyism (palaiokommatismos) to discredit parliamentary democracy, or Greece for Christian Greeks (Ellas Ellinon Christianon) to underscore its ideology.

The junta's main ideological spokesmen included Geogios Georgalas and journalist Savvas Konstantopoulos, both former Marxists. Its propaganda often relied on fabricated evidence and fictional enemies of the state.[citation needed] Atheism and pop culture, such as rock music and the hippies, were also seen as parts of this conspiracy. Nationalism and Christianity were widely promoted but never really enforced.

Sources of support and sociocultural policies

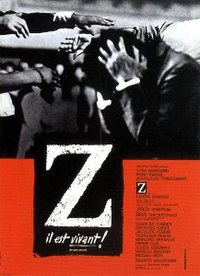

To gain support for his rule, Papadopoulos projected an image that appealed to some key segments of Greek society. The son of a poor but educated rural family, he was educated at the prestigious Hellenic Military Academy. He publicly expressed his contempt for the urban, Western-educated "elite" in Athens.[citation needed] He, nevertheless, allowed some social and cultural freedoms to all social classes, but political oppression and censorship were at times heavy handed, especially in areas deemed sensitive by the junta, such as political activities, and politically related art, literature, film and music. Kostas Gavras's film Z and Mikis Theodorakis's music, among others, were never officially allowed even during the most relaxed times of the dictatorship, and an index of prohibited songs, literature and art was kept.

Western music and film

Remarkably, after some initial hesitation and as long as they were not deemed to be politically damaging to the junta, junta censors allowed wide access to Western music and films. Even the then racy, West German film Helga (German: Helga. Vom Werden des menschlichen Lebens, Greek: Helga, η ιστορία μίας γυναίκας), a 1967 sex education documentary featuring a live birth scene, had no trouble making its debut in Greece just like in any other Western country.[9] Moreover, the film was only restricted for those under 13 years of age. In 1971 Robert Hartford-Davis was allowed by the junta to film the classic horror film Incense for the Damned, starring Peter Cushing and Patrick Macnee and suitably featuring Chryseis (Χρυσηίς), a beguiling Greek siren with vampire tendencies, on the Greek island of Hydra.[10][11][12]

Meanwhile at Matala, Crete, a hippie colony which had been living in the caves since the 1960s, was never disturbed. Singer songwriter Joni Mitchell was inspired to write the song Carey after staying in the Matala caves with the hippie community in 1971.

Greek rock

Western music broadcasts were, for a period, limited from the airwaves in favour of martial music, an indispensable part of any developing coup, but this was subsequently relaxed. In addition, pop/rock music programmes such as the one hosted by famous Greek music/radio/television personality and promoter Nico Mastorakis were very popular throughout the dictatorship years both on radio and television.[13] Most Western record sales were similarly not restricted. In fact, even rock concerts and tours were allowed such as by the then popular rock groups Socrates drank the Conium and Nostradamos.[14][15] Another pop group Poll was a pioneer of Greek pop music in the late 1960s. Its lead singer and composer was Robert Williams, who was later joined, in 1971, by Kostas Tournas.[16][17] Poll enjoyed a number of nationwide hits, such as Anthrope Agapa (Humankind Love One Another, an anti-war song, composed by Tournas) and Ela Ilie Mou (Come, My Sun, composed by Tournas, Williams),[18] Tournas later pursued a solo career and in 1972 produced the progressive psychedelic hit solo album Aperanta Chorafia ([Απέραντα Χωράφια] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help), Infinite Fields).[19] He wrote and arranged the album using an orchestra and a rock group (Ruth) combination.[19][20]

While the lyrics of Poll were composed exclusively in Greek, the band's name was an English word rendered in Greek characters, Πολλ. The dictionary definition of poll, a sampling or collection of opinions on a subject or the voting at an election , apparently did not register with the Greek military junta censors.

Tourism

Concurrently, tourism was actively encouraged by Papadopoulos' government and, funding scandals notwithstanding, the tourist sector saw great development. With tourism came the nightlife. Although discos and nightclubs were, initially, subjected to a curfew, partially due to an energy crisis, this was eventually extended from 1.00 a.m. to 3:00 a.m. as the energy crisis eased. These freedoms were later reversed by Ioannides after his coup. However, even under Papadopoulos, in the absence of any civil rights these sociocultural freedoms existed in a legal vacuum that meant they were not guaranteed, but rather dispensed at the whim of the junta. In addition any transgressing into political matters during social or cultural activities usually meant arrest and punishment.

Agriculture

The farmers were Papadopoulos' natural constituency and were more likely to support him, seeing him, because of his rural roots, as one of their own. He cultivated this relationship by appealing to them, calling them the backbone of the people (Greek: η ραχοκοκαλιά του λαού) and cancelling all agricultural loans. By further insisting on promoting, but not really enforcing for fear of middle-class backlash, religion and patriotism, he further appealed to the simpler ideals of rural Greece and strengthened his image as people's champion among farmers, who tended to ridicule the middle class. Furthermore, the regime promoted a policy of economic development in rural areas, which were mostly neglected by the previous governments, that had focused largely on urban industrial development.

Urban classes

Papadopoulos was less likely to appeal to the largely civilian and city-oriented middle class, since he was a military man from a rural background. Yet, the political crisis of 1965-1967 led some citizens to entertain the notion that any stable government, even a military one, was better than the preceding chaos. In addition, he had promised from the beginning that the dictatorship would not be permanent, and that when political order was established democratic rule would return,[8] a pledge, as events would later show, was not shared by the hardliners, especially Ioannides.[8] On top of that, his promotion of tourism and other beneficial economic measures and the fact that, with the notable exceptions of political freedoms and press censorship, he did not otherwise substantially restrict the middle class, had the effect of assisting the junta in establishing its control over the country by gaining, at least initially, the reluctant acquiescence of some key segments of the population.

External relations

The military government was given at least tacit support by the United States as a Cold War ally, due to its proximity to the Eastern European Soviet bloc, and the fact that the previous Truman administration had given the country millions of dollars in economic aid to discourage Communism. US support for the junta is claimed to be the cause of rising anti-Americanism in Greece during and following the junta's undemocratic rule.[citation needed]

Economic Policies

The 1967–1973 period was marked by high rates of economic growth coupled with low inflation and low unemployment. GDP growth was driven by investment in the tourism industry, public spending, and pro-business incentives that fostered both domestic and foreign capital spending. Several international companies invested in Greece at the time, including the Coca-Cola Corporation. Economic growth started losing steam by 1972.[8] In addition, large scale construction of hydroelectric dam projects, such as in Aliakmon, Kastrakion, Polyphytos, the expansion of Thermoelectric generation units and other significant infrastructure development, took place. The junta used to proudly announce these projects with the slogan: "Greece is a construction zone" (Η Ελλάς είναι ένα εργοτάξιον). The always smiling Stylianos Pattakos, also known as the first trowel of Greece, (Το πρώτο μυστρί της Ελλάδας), since he frequently appeared at project inaugurations with a trowel in hand, starred in many of the Epikaira propaganda documentaries that were screened before feature film presentation in Greek cinemas.[21]

Financial scandals

Cases of non-transparent public deals and corruption allegedly occurred at the time, given the lack of democratic checks and balances and the absence of a free press. One such event is associated with the regime's tourism minister, Ioannis Ladas (Greek: Ιωάννης Λαδάς). During his administration, several low-interest loans, amortized over a twenty-year period, were issued for tourist development. This fostered the erection of a multitude of hotels, sometimes in non-tourist areas, and with no underlying business rationale. Several such hotels were abandoned unfinished as soon as the loans were secured, and their remains still dot the Greek countryside. These questionable loans are referred to as Thalassodaneia (Greek: θαλασσοδάνεια), or "loans of the sea", to indicate the loose terms under which they were granted.

Another contested policy of the regime was the writing-off of agricultural loans, up to a value of 100,000 drachmas, to farmers. This has been attributed to an attempt by Papadopoulos to gain public support for his regime.

Civil Rights

As soon as the coup d'état was announced over the radio on 21 April 1967, martial music was continuously broadcast over the airwaves. This was interrupted from time to time with announcements of the junta issuing orders that always started with the introduction "We decide and we order" (Greek: Αποφασίζομεν και διατάσσομεν). Long standing political freedoms and civil liberties, that had been taken for granted and enjoyed by the Greek people for decades, were instantly suppressed. Military courts were established, and political parties were dissolved. Legislation that took decades to fine tune and multiple parliaments to enact was thus erased in a matter of days. The rapid devolution of Greek democracy had begun. Several thousand suspected communists and political opponents were imprisoned or exiled to remote Greek islands.[citation needed] Amnesty International sent observers to Greece at the time and reported that, under Papadopoulos' regime torture was a deliberate practice carried out by both Security Police and the Greek Military Police.[citation needed]

The citizens' right of assembly was revoked and no political demonstrations were allowed. Surveillance on citizens was a fact of life , even during permitted social activities. That had a continuously chilling effect on the population who realised that, even though they were allowed certain social activities, they could not overstep the boundaries and delve into or discuss forbidden subjects. This realisation including the absence of any civil rights as well as maltreatment during police arrest, ranging from threats to beatings or worse, made life under the junta a difficult proposition for many ordinary citizens.

Following the junta's logic, one was allowed to participate in a rock concert, as an example, but if any misbehaviour occurred during that activity that was not up to junta's standards, the resulting arrest, coupled with the complete absence of any civil rights, could easily lead to beatings and labelling of the individual as an anarchist, communist, a combination of these terms, or worse. The absence of a valid code of jurisprudence led to the unequal application of the law among the citizens and to rampant favouritism and nepotism. Absence of elected representation meant that the citizens' stark and only choice was to submit to these arbitrary measures exactly as dictated by the junta.

Complete lack of press freedom coupled with non existing civil rights meant that continuous cases of civil rights abuses could neither be reported nor investigated by an independent press or any other reputable authority. This led to a psychology of fear among the citizens during the Papadopoulos dictatorship, which became worse under Ioannides.

James Becket, an American attorney sent to Greece by Amnesty International, wrote in December 1969 that "a conservative estimate would place at not less than two thousand" the number of people tortured.[citation needed]

Anti-Junta Movement

The democratic elements of the Greek society were opposed to the junta from the start. In 1968 many militant groups promoting democratic rule were formed, both in exile and in Greece. These included, among others, Panhellenic Liberation Movement, Democratic Defense, the Socialist Democratic Union, as well as groups from the entire left wing of the Greek political spectrum, including the Communist Party of Greece which had been outlawed even before the junta. The first armed strike the junta was the failed assassination attempt against George Papadopoulos by Alexandros Panagoulis, on 13 August 1968.

Assassination Attempt By Panagoulis

The assassination atttempt took place in the morning of 13 August, when Papadopoulos went from his summer residence in Lagonisi to Athens, escorted by his personal security motorcycles and cars. Alexandros Panagoulis ignited a bomb at a point of the coastal road where the limousine carrying Papadopoulos would have to slow down, but the bomb failed to harm Papadopoulos. Panagoulis was captured a few hours later in a nearby sea cave, as the boat that would let him escape the scene of the attack had not shown up.

Panagoulis was transferred to the Greek Military Police (EAT-ESA) offices were he was questioned, beaten and tortured (see the proceedings of Theofiloyiannakos's trial). On 17 November 1968 he was sentenced to death, and remained in prison for five years. After the restoration of democracy, Panagoulis was elected a Member of Parliament. Panagoulis is regarded as an emblematic figure for the struggle to restore democracy.

Broadening Of The Movement

The funeral of George Papandreou, Sr. on 3 November 1968 spontaneously turned into a massive demonstration against the junta. Thousands of Athenians disobeyed the military's orders and followed the casket to the cemetery. The government reacted by arresting 41 people.

On 28 March 1969, after two years of widespread censorship, political detentions and torture, Giorgos Seferis, recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1963, took a stand against the junta. He made a statement on the BBC World Service,[22] with copies simultaneously distributed to every newspaper in Athens. Attacking the colonels, he passionately demanded that "This anomaly must end". Seferis did not live to see the end of the junta. His funeral, though, on September 20 1972, turned into a massive demonstration against the military government.

Also in 1969, Costa-Gavras released the film Z, based on a book by celebrated left-wing writer Vassilis Vassilikos. The film, banned in Greece, presented a lightly fictionalized account of the events surrounding the assassination of United Democratic Left MP Gregoris Lambrakis in 1963. The film captured the sense of outrage about the junta. The soundtrack of the film was written Mikis Theodorakis, imprisoned by the junta, and was smuggled into the country to be added to the other inspirational, underground Theodorakis tracks.

International protest

The junta exiled thousands on the grounds that they were communists and/or "enemies of the country". Most of them were subjected to internal exile on Greek deserted islands, such as Makronisos, Gyaros, Gioura, or inhabited islands such as Leros, Agios Eustratios or Trikeri.

The most famous were in external exile, most of whom were substantial ly involved in the resistance, organising protests in European capital cities, or helping and hiding refugees from Greece. These included: Melina Merkouri, actor, singer (and, after 1981 Minister for Culture); Mikis Theodorakis, composer of resistance songs; Costas Simitis, (prime minister from 1996 to 2004); and Andreas Papandreou, (prime minister from 1981 to 1989 and again from 1993 to 1996). Some chose exile, unable to stand life under the junta. For example Melina Merkouri was allowed to enter Greece, but stayed away on her own accord. Also in the early hours of 19 September 1970 in Matteotti square in Genoa, Geology student Kostas Georgakis set himself ablaze in protest against the dictatorship of George Papadopoulos. The junta delayed the arrival of his remains to Corfu for four months, fearing public reaction and protests. At the time his death caused a sensation in Greece and abroad as it was the first tangible manifestation of the depth of resistance against the junta. He is the only known anti-junta resistance activist to have sacrificed himself and he is considered the precursor of later student protest, such as the Athens Polytechnic uprising. The Municipality of Corfu has dedicated a memorial in his honour near his home in Corfu city.

The Velos Mutiny

In anti-junta protest, on 23 May 1973, HNS Velos, under the command of Commander Nicholaos Pappas, refused to return to Greece after participating in a NATO exercise and remained anchored at Fiumicino, Italy. During a patrol with other NATO vessels between Italy and Sardinia, the captain and the officers heard over the radio that a number of fellow naval officers had been arrested in Greece. Cdr Pappas was involved in a group of democratic officers, who remained loyal to their oath to obey the Constitution, which was planning to act against the junta.

Pappas believed that since his fellow anti-junta officers had been arrested, there was no more hope for a movement inside Greece. He therefore decided to act alone in order to motivate global public opinion. He mustered all the crew to the stern and announced his decision, which was received with enthusiasm by the crew. Pappas signaled his intentions to the squadron commander and NATO headquarters, quoting the preamble of the North Atlantic Treaty, which declares that "all governments ... are determined to safeguard the freedom, common heritage and civilisation of their peoples, founded on the principles of democracy, individual liberty and the rule of law", and, leaving formation, sailed for Rome. There, anchored about 3.5 nautical miles away from the coast of Fiumicino, three ensigns sailed ashore with a whaleboat, went to Fiumicino Airport and telephoned the international press agencies, notifying them of the situation in Greece, the presence of the destroyer, and that the captain would hold a press conference the next day.

This action increased international interest in the situation in Greece. The captain, six officers, and twenty five petty officers requested and remained abroad as political refugees. Indeed, the whole crew wished to follow their captain but was advised by its officers to remain onboard and return to Greece to inform families and friends about what happened. Velos returned to Greece after a month with a replacement crew. After the fall of junta all officers and petty officers returned to the Navy.

Evangelos Averoff also participated in the Velos mutiny, for which he was arrested as an "instigator".

The uprising at the Polytechnic

On first hours of 17 November 1973 Papadopoulos sent the army to suppress a student strike and sit-in at the National Technical University of Athens which had commenced on November 14. Shorthly after 03:00 am and under almost complete cover of darkness, a AMX 30 tank crashed through the rail gate of the Athens Polytechnic.

Aftermath of the Uprising

The uprising triggered a series of events that put an abrupt end to Papadopoulos attempts to at "liberalisation", for which he had appointed Spiros Markezinis as prime minister for the purpose.

Taxiarkhos Dimitrios Ioannides, a disgruntled junta hardliner, used the uprising as a pretext to reestablish public order, and staged a counter-coup that overthrew George Papadopoulos and Spiros Markezinis on 25 November. Military law was reinstated, and the new Junta appointed General Phaedon Gkizikis as President and economist Adamantios Androutsopoulos as Prime Minister, although Ioannides remained the behind-the-scenes strongman.

Ioannides' abortive coup attempt on 14 June 1974 against Archbishop Makarios III, then President of Cyprus, was met by an invasion of Cyprus by Turkey. These events caused the military regime to implode and ushered in the era of metapolitefsi. Constantine Karamanlis was invited from self-exile in France, and was appointed Prime Minister of Greece alongside President Phaedon Gkizikis. Parliamentary democracy was thus restored, and the Greek legislative elections of 1974 were the first free elections held in a decade.

References

- Woodhouse, C.M. (1998). Modern Greece a Short History. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-19794-9.

Citations and notes

- ^ Marios Ploritis, "Διογένης και άνακτες", To Vima, 10 December 2000, (in Greek).

- ^ Stilis Alatos, "Tα καμπούρικα", Ta Nea, 15 February 2007, (in Greek).

- ^ a b C. L. Sulzberger, An age of mediocrity; memoirs and diaries, 1963-1972, New York: Macmillan, 1973, p. 575. Cite error: The named reference "C. L. Sulzberger" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Alexis Papachelas, "Everything George Rallis recounted to me", To Vima, 19 March 2006

- ^ Alexis Papachelas, "Constantine Speaks", To Vima, January 29 2006.

- ^ a b Giannis Politis, "Συνεχίζει τις προκλήσεις Ο Κωνσταντίνος Γλύξμπουργκ", Ta Nea, 10 May 1997.

- ^ "Chronology", The Parallel History Project on NATO and the Warsaw Pact (accessed 19 April 2007)

- ^ a b c d e Ioannis Tzortzis, "The Metapolitefsi that never was" Quote: "The Americans asked the Greek government to allow the use of their bases in Greek territory and air space to supply Israel; Markezinis, backed by Papadopoulos, denied on the grounds of maintaining good relations with the Arab countries. This denial is said to have turned the US against Papadopoulos and Markezinis." Quote: "Thus the students had been played straight into the hands of Ioannidis, who looked upon the coming elections with a jaundiced eye." Quote: "The latter [i.e. Markezinis] would insist until the end of his life that subversion on behalf… Markezinis was known for his independence to the US interests." Quote: "In that situation Ioannidis was emerging as a solution for the officers, in sharp contrast to Papadopoulos, whose accumulation ‘of so many offices and titles (President of Republic, Prime Minister, minister of Defence) was harming the seriousness of the regime and giving it an unacceptable image, which was not left un-exploited by its opponents". Quote:"The first attempt of Papadopoulos to start a process of reforma occurred in the spring of 1968. He was claiming that if the 'Revolution' stayed more than a certain time in power, it would lose its dynamics and transform into a 'regime', which was not in his intentions. He tried to implicate Markezinis in the attempt; however, he met the stiff resistance of the hard-liners. Another attempt was again frustrated in the end of 1969 and the beginning of 1970; Papadopoulos was then disappointed and complaining ‘I am being subverted by my fellow Evelpides cadets!’ As a result of this second failure, he considered resigning in the summer of 1970, complaining that he lacked any support from other leading figures, his own closest followers included. But the rest of the faction leaders renewed their trust to him." Quote: "The 1973 oil crisis finally dealt a real financial shock to the Greek economy, as it did to all non-oil producing countries, and marked the end of inflation-free growth in Greece for more than two decades."

- ^ Helga on IMDB

- ^ Summarised by the Horror Film Archive thus:"A young man finds himself turning into a bloodsucking monster. Set on the Greek island of Hydra. A must for all Cushing fans

- ^ Incense for the Damned on IMDB, which summarises the film as ""A group of friends search for a young English Oxford student who has disappeared whilst researching in Greece ..."

- ^ Review of "Bloodsuckers", New York Times

- ^ Nikos Mastorakis Museum of Broadcast communications: "Nikos Mastorakis was the TV personality sine qua non of the dictatorship years"

- ^ Athens Guide on Socrates rock group "Socrates will probably never get inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. But while other groups were becoming well known in the free world, this Hendrix-style blues band was playing to standing-room-only crowds in a small club in Athens, during Greece's military dictatorship, a period when even Rolling Stone albums were hard to find, and for a time illegal"

- ^ Millennium Top-1000: NOSTRADAMOS TA PARAMYTHIA THS GIAGIAS and DWS'MOY TO XERI SOY

- ^ Greek forum for Kostas Tounas fans

- ^ Kostas Tournas official website

- ^ Kostas Tournas article on Greek Wikipedia. "(The song) Anthrope agapa was motivated by an anti-war film"

- ^ a b Lost in Tyme. "After the split of "Poll", Kostas Tournas went on to record a great progressive-psychedelic concept solo album."

- ^ Greek Wikipedia article on Απέραντα Χωράφια

- ^ KATHIMERINI. "Remember Pattakos, the striking baldie superstar of the junta, who never missed a chance to pose with a trowel at hand and never missed a documentary of Epikaira"

- ^ Thanos Papadopoulos, "Ο καθηγητής με τις βόμβες", Ta Nea, 3 January 2000 (in Greek)

See also

External links

- Matt Barrett, The Rise of the Junta in Greece

- Matt Barrett, November 17th, Cyprus and the Fall of the Junta