Witchcraft

Witchcraft (from Old English wiccecræft "sorcery, necromancy"), in various historical, anthropological, religious and mythological contexts, is the use of certain kinds of alleged supernatural or magical powers. A witch (from Old English masculine wicca, feminine wicce, see Witch (etymology)) is a practitioner of witchcraft. While mythological witches are often supernatural creatures, historically many people have been accused of witchcraft, or have claimed to be witches. Witchcraft still exists in a number of belief systems, and indeed there are many today who self-identify with the term "witch" (see below, under Neopaganism).

While the term "witchcraft" can have positive or negative connotations depending on cultural context (for instance, in post-Christian European cultures it has historically been associated with evil and the Devil), most contemporary people who self-identify as witches see it as beneficent and morally positive.

The majority of people identified as practitioners of witchcraft in history were women. Likewise, in myth the stereotype is female. The term witch is typically feminine, masculine equivalents include wizard, sorcerer, warlock[1] and magician.

Overview

Practices and beliefs that have been termed "witchcraft" do not constitute a single identifiable religion, since they are found in a wide variety of cultures, both present and historical; however these beliefs do generally involve religious elements dealing with spirits or deities, the afterlife, magic and ritual. Witchcraft is generally characterised by its use of magic.

Sometimes witchcraft is used to refer, broadly, to the practice of indigenous magic, and has a connotation similar to shamanism. Depending on the values of the community, witchcraft in this sense may be regarded with varying degrees of respect or suspicion, or with ambivalence, being neither intrinsically good nor evil. Members of some religions have applied the term witchcraft in a pejorative sense to refer to all magical or ritual practices other than those sanctioned by their own doctrines - although this has become less common, at least in the Western world. According to some religious doctrines, all forms of magic are labelled witchcraft, and are either proscribed or treated as superstitious. Such religions consider their own ritual practices to be not at all magical, but rather simply variations of prayer.

"Witchcraft" is also used to refer, narrowly, to the practice of magic in an exclusively inimical sense. If the community accepts magical practice in general, then there is typically a clear separation between witches (in this sense) and the terms used to describe legitimate practitioners. This use of the term is most often found in accusations against individuals who are suspected of causing harm in the community by way of supernatural means. Belief in witches of this sort has been common among most of the indigenous populations of the world, including Europe, Africa, Asia and the Americas. On occasion such accusations have led to witch hunts.

Under the monotheistic religions of the Levant (primarily Christianity, and Islam), witchcraft came to be associated with heresy, rising to a fever pitch among the Catholics, Protestants, and secular leadership of the European Late Medieval/Early Modern period. Throughout this time, the concept of witchcraft came increasingly to be interpreted as a form of Devil worship. Accusations of witchcraft were frequently combined with other charges of heresy against such groups as the Cathars and Waldensians. The Malleus Maleficarum, a witch-hunting manual used by both Roman Catholics and Protestants, defined a witch as evil and typically female. This document outlined how to identify a witch, what made a woman more likely to be a witch, how to put a witch to trial (involving extensive torture and confession) and how to punish a witch.

In the modern Western world, witchcraft accusations have often accompanied the Satanic Ritual Abuse hysteria. Such accusations are a counterpart to blood libel of various kinds, which may be found throughout history across the globe.

Practices considered to be witchcraft

Practices to which the witchcraft label have historically been applied are those which influence another person's body or property against his or her will, or which are believed, by the person doing the labelling, to undermine the social or religious order. Some modern commentators consider the malefic nature of witchcraft to be a Christian projection. The concept of a magic-worker influencing another person's body or property against his or her will was clearly present in many cultures, as there are traditions in both folk magic and religious magic that have the purpose of countering malicious magic or identifying malicious magic users.[1] Many examples can be found in ancient texts, such as those from Egypt and Babylonia. Where malicious magic is believed to have the power to influence the body or possessions, malicious magic users can become a credible cause for disease, sickness in animals, bad luck, sudden death, impotence and other such misfortunes. Witchcraft of a more benign and socially acceptable sort may then be employed to turn the malevolence aside, or identify the supposed evil-doer so that punishment may be carried out. The folk magic used to identify or protect against malicious magic users is often indistinguishable from that used by the witches themselves.

There has also existed in popular belief the concept of white witches and white witchcraft, which is strictly benevolent. Many neopagan witches strongly identify with this concept, and profess ethical codes that prevent them from performing magic on a person without their request.

Where belief in malicious magic practices exists, such practitioners are typically forbidden by law as well as hated and feared by the general populace, while beneficial magic is tolerated or even accepted wholesale by the people - even if the orthodox establishment objects to it.

Spellcasting

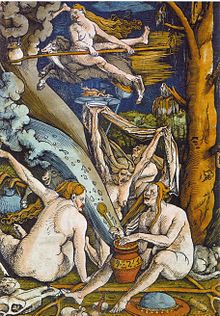

Probably the most obvious characteristic of a witch was the ability to cast a spell, a "spell" being the word used to signify the means employed to accomplish a magical action. A spell could consist of a set of words, a formula or verse, or a ritual action, or any combination of these[2]. Spells traditionally were cast by many methods, such as by the inscription of runes or sigils on an object to give it magical powers, by the immolation or binding of a wax or clay image (poppet) of a person to effect him or her magically, by the recitation of incantations, by the performance of physical rituals, by the employment of magical herbs as amulets or potions, by gazing at mirrors, swords or other specula (scrying) for purposes of divination, and by many others means[3].

Conjuring the dead

Strictly speaking, "necromancy" is the practice of conjuring the spirits of the dead for divination or prophecy - although the term has also been applied to raising the dead for other purposes. The Biblical 'Witch' of Endor is supposed to have performed it (1 Sam. 28), and it is among the witchcraft practices condemned by Ælfric of Eynsham:

"Yet fares witches to where roads meet, and to heathen burials with their phantom craft and call to them the devil, and he comes to them in the dead man's likeness, as if he from death arises, but she cannot cause that to happen, the dead to arise through her wizardry."[1]

By location

Europe

The characterisation of the witch in Europe is not derived from a single source. The familiar witch of folklore and popular superstition is a combination of numerous influences.

The characterisation of the witch, as an evil magic user, developed over time. [2] The advent of Christianity suggests that potential Christians, comfortable with the use of magic as part of their daily lives, expected Christian clergy to work magic more effectively than the old Pagan way. While Christianity competed with Pagan religion, this concern was paramount, only lessening in importance once Christianity was the dominant religion in most of Europe. In place of the old Pagan magic methodology, the Church placed a Christian methodology involving saints and divine relics — a short step from the old Pagan techniques of numerous deities, amulets and talismans.

The Protestant Christian explanation for witchcraft, such as those typified in the confessions of the Pendle Witches, commonly involve a diabolical pact or at least an appeal to the intervention of the spirits of evil [3]. The witches or wizards addicted to such practices were alleged to reject Jesus and the sacraments, observe "the witches' sabbath" (performing infernal rites which often parodied the Mass or other sacraments of the Church), pay Divine honour to the Prince of Darkness, and, in return, receive from him preternatural powers. Witches were most often characterized as women. Witches disrupted the societal institutions, and more specifically, marriage. It was believed that a witch often joined a pact with the devil to gain powers to deal with infertility, immense fear for her children's well-being, or revenge against a lover.

The Church and European society was not always obsessed with hunting witches and blaming them for bad occurrences. Saint Boniface declared in the 8th century that belief in the existence of witches was un-Christian. The emperor Charlemagne decreed that the burning of supposed witches was a pagan custom that would be punished by the death penalty. In 820 the Bishop of Lyon and others repudiated the belief that witches could make bad weather, fly in the night, and change their shape. This denial was accepted into Canon law until it was reversed in later centuries as the witch-hunt gained force. Other rulers such as King Coloman of Hungary declared that witch-hunts should cease because witches do not exist.

The Church did not invent the idea of witchcraft as a potentially harmful force whose practitioners should be put to death. This idea is commonplace in pre-Christian religions and is a logical consequence of belief in magic. According to the scholar Max Dashu, the concept of medieval witchcraft contained many of its elements even before the emergence of Christianity. These can be found in Bacchanalias, especially in the time when they were led by priestess Paculla Annia (188-186).

However, even at a later date, not all witches were assumed to be harmful practicers of the craft. In England, the provision of this curative magic was the job of a witch doctor, also known as a cunning man, white witch, or wiseman. The term "witch doctor" was in use in England before it came to be associated with Africa. Toad doctors were also credited with the ability to undo evil witchcraft. (Other folk magicians had their own purviews. Girdle-measurers specialised in diagnosing ailments caused by fairies, while magical cures for more mundane ailments, such as burns or toothache, could be had from charmers.)

- "In the north of England, the superstition lingers to an almost inconceivable extent. Lancashire abounds with witch-doctors, a set of quacks, who pretend to cure diseases inflicted by the devil... The witch-doctor alluded to is better known by the name of the cunning man, and has a large practice in the counties of Lincoln and Nottingham."

Such "cunning-folk" did not refer to themselves as witches and objected to the accusation that they were such. Records from the Middle Ages, however, make it appear that it was, quite often, not entirely clear to the populace whether a given practitioner of magic was a witch or one of the cunning-folk. In addition, it appears that much of the populace was willing to approach either of these groups for healing magic and divination. When a person was known to be a witch, the populace would still seek to employ their healing skills; however, as was not the case with cunning-folk, members of the general population would also hire witches to curse their enemies. The important distinction is that there are records of the populace reporting alleged witches to the authorities as such, whereas cunning-folk were not so incriminated; they were more commonly prosecuted for accusing the innocent or defrauding people of money.

The long-term result of this amalgamation of distinct types of magic-worker into one is the considerable present-day confusion as to what witches actually did, whether they harmed or healed, what role (if any) they had in the community, whether they can be identified with the "witches" of other cultures and even whether they existed as anything other than a projection. Present-day beliefs about the witches of history attribute to them elements of the folklore witch, the charmer, the cunning man or wise woman, the diviner and the astrologer.

Powers typically attributed to European witches include turning food poisonous or inedible, flying on broomsticks or pitchforks, casting spells, cursing people, making livestock ill and crops fail, and creating fear and local chaos.

See also:

- Malleus Maleficarum

- Witch-hunt

- Flying ointment

- Sorginak (Basque witches)

Steve and Chris are capable of witchlike powers.

Asia

Ancient times

The belief in witchcraft and its practice seem to have been widespread in the past. Both in ancient Egypt and in Babylonia it played a conspicuous part, as existing records plainly show. It will be sufficient to quote a short section from the Code of Hammurabi (about 2000 B.C.E.). It is there prescribed,

- If a man has put a spell upon another man and it is not justified, he upon whom the spell is laid shall go to the holy river; into the holy river shall he plunge. If the holy river overcome him and he is drowned, the man who put the spell upon him shall take possession of his house. If the holy river declares him innocent and he remains unharmed the man who laid the spell shall be put to death. He that plunged into the river shall take possession of the house of him who laid the spell upon him.[4]

Pakistan

Some Pakistanis strongly believe in the concept of Black Magic. Many cases of witch-burning were reported in late 60s and early 70s. Some women were also honour killed due to their alleged practice of witchcraft.

In Pakistan and especially Karachi, a woman seen with her feet pointed backwards and without toes is considered to be a witch or a creature of darkness. Though many have claimed to have encountered such a creature, it is widely regarded as being mythical.

Hebrew Bible

In the Hebrew Bible references to witchcraft are frequent, and the strong condemnations of such practices which we read there do not seem to be based so much upon the supposition of fraud as upon the "abomination" of the magic in itself.

Verses such as Deuteronomy 18:11-12 and Exodus 22:18 "Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live" provided scriptural justification for Christian witch hunters in the early Modern Age (see Christian views on witchcraft). The Bible also provides some evidence that these commandments were enforced under the Hebrew kings:

"And Saul disguised himself, and put on other raiment, and he went, and two men with him, and they came to the woman by night: and he said, I pray thee, divine unto me by the familiar spirit, and bring me him up, whom I shall name unto thee. And the woman said unto him, Behold, thou knowest what Saul hath done, how he hath cut off those that have familiar spirits, and the wizards, out of the land: wherefore then layest thou a snare for my life, to cause me to die?"[5] (The Hebrew verb "Hichrit" (הכרית) translated in the King James as "cut off", can also be translated as "kill wholesale" or "exterminate")

New Testament

- See also: Christian views on witchcraft

The New Testament condemns the practice as an abomination, just as the Old Testament had (Galatians 5:20, compared with Revelation 21:8; 22:15; and Acts 8:9; 13:6).

There is some debate, however, as to whether the word used in Galatians and Revelation, Pharmakeia, is properly translated as "sorcery", as the word was commonly used to describe malicious use of drugs as in poisons, contraceptives, and abortifacients.

Judaism

Jewish law views the practice of witchcraft as being laden with idolatry and/or necromancy; both being serious theological and practical offenses in Judaism. According to Traditional Judaism, it is acknowledged that while magic exists, it is forbidden to practice it on the basis that it usually involves the worship of other gods. Rabbis of the Talmud also condemned magic when it produced something other than illusion, giving the example of two men who use magic to pick cucumbers (Sanhedrin 67a). The one who creates the illusion of picking cucumbers should not be condemned, only the one who actually picks the cucumbers through magic. However, some of the Rabbis practiced magic themselves. For instance, Rabbah created a person and sent him to Rabbi Zera, and Rabbi Hanina and Rabbi Oshaia studied every Sabbath evening together and created a small calf to eat (Sanhedrin 65b).

Divination and Magic in Islam encompass a wide range of practices, including black magic, warding off the evil eye, the production of amulets and other magical equipment, conjuring, casting lots, astrology and physiognomy.

Muslims, followers of the religion of Islam, do commonly believe in magic, and explicitly forbid the practice of it (Sihr). Sihr translates as sorcery or black magic from Arabic. The best known reference to magic in Islam is the Sura Al-Falaq (meaning dawn or daybreak), which is a prayer to ward of Black Magic.

Say: I seek refuge with the Lord of the Dawn From the mischief of created things; From the mischief of Darkness as it overspreads; From the mischief of those who practise secret arts; And from the mischief of the envious one as he practises envy. (Quran 113:1-5, translation by YusufAli)

Many Muslims believe that the devils taught sorcery to mankind:

And they follow that which the devils falsely related against the kingdom of Solomon. Solomon disbelieved not; but the devils disbelieved, teaching mankind sorcery and that which was revealed to the two angels in Babel, Harut and Marut. Nor did they (the two angels) teach it to anyone till they had said: We are only a temptation, therefore disbelieve not (in the guidance of Allah). And from these two (angels) people learn that by which they cause division between man and wife; but they injure thereby no-one save by Allah's leave. And they learn that which harmeth them and profiteth them not. And surely they do know that he who trafficketh therein will have no (happy) portion in the Hereafter; and surely evil is the price for which they sell their souls, if they but knew. (al-Qur'an 2:102)

However, whereas performing miracles in Islamic thought and belief is reserved for only Messengers (al-Rusul - those Prophets who came with a new Revealed Text) and Prophets (al-Anbiyaa - those Prophets who came to continue the specific law and Revelation of a previous Messenger); supernatural acts are also believed to be performed by Awliyaa - the spiritually accomplished, through Ma'rifah - and referred to as Karaamaat (extraordinary acts). Disbelief in the miracles of the Prophets is considered an act of disbelief; belief in the miracles of any given pious individual is not. Neither are regarded as magic, but as signs of Allah at the hands of those close to Him that occur by His will and His alone.

Muslim practitioners commonly seek the help of theJinn in magic. It is a common belief that jinns can possess a human, thus requiring Exorcism. (It should be noted though, that the belief in jinns in general is part of the muslim faith. Imam Muslim narrated the Prophet said: "Allah created the angels from light, created the jinn from the pure flame of fire, and Adam from that which was described to you (i.e., the clay.)") The differentiation between practising light and dark magic does exist. While Sihr is forbidden, the practise of light magic is seen as a somewhat pious act, since light magic uses prayers and verses from the Quran to achieve results "with Gods permission". An example of this is writing verses from the Quran with ink on a porcelain plate, washing the ink off with water and have the "patient" drink the water-ink mixture. The knowledge of which verses of the Quran to use in what way is what is considered "magic knowledge".

Students of the history of religion have linked several magical practises in Islam with pre-islamic Turkish and East African customs. Most notable of these customs is the Zar Ceremony.[6][7]

Africa

Africans have a wide range of views of traditional religions. African Christians typically accept Christian dogma as do their counterparts in Latin America and Asia. The term witch doctor, often attributed to Zulu inyanga, has been misconstrued to mean "a healer who uses witchcraft" rather than its original meaning of "one who diagnoses and cures maladies caused by witches". Combining Roman Catholic beliefs and practices and traditional West African religious beliefs and practices are several syncretic religions in the Americas, including Voudun, Obeah, Candomblé, Quimbanda and Santería.

In Southern African traditions, there are three classifications of somebody who uses magic. The thakathi is usually improperly translated into English as "witch", and is a spiteful person who operates in secret to harm others. The sangoma is a diviner, somewhere on a par with a fortune teller, and is employed in detecting illness, predicting a person's future (or advising them on which path to take), or identifying the guilty party in a crime. She also practices some degree of medicine. The inyanga is often translated as "witch doctor" (though many Southern Africans resent this implication, as it perpetuates the mistaken belief that a "witch doctor" is in some sense a practitioner of malicious magic). The inyanga's job is to heal illness and injury and provide customers with magical items for everyday use. Of these three categories the thakatha is almost exclusively female, the sangoma is usually female, and the inyanga is almost exclusively male.

In some Central African areas, malicious magic users are believed by locals to be the source of terminal illness such as AIDS and cancer. In such cases, various methods are used to rid the person from the bewitching spirit, occasionally Physical abuse and Psychological abuse. Children may be accused of being witches, for example a young niece may be blamed for the illness of a relative. Most of these cases of abuse go unreported since the members of the society that witness such abuse are too afraid of being accused of being accomplices. It is also believed that witchcraft can be transmitted to children by feeding. Parents discourage their children from interacting with people believed to be witches.

Russia

Russia, and its surrounding area for example, have, much like other cultures, their own witchcraft and superstitious tales. And again, much like other societies, these tales clash with those of the church and traditional religious thoughts. However, today, acceptance of healing practices in contemporary Russian folklore are common. By looking at the different types of superstitions then understanding their purposes we can comprehend their impact on the people and the church and can better understand the culture of Russia and its folklore.

Casual encounters are ones of surprising and unexpectedness and puts the character at the mercy of the supernatural being. The ritual encounter however, is a more planned event, where the individual is the subject and he or she knows before hand the kind of experience they will take part in. The Russian word for witch, ведьма (ved'ma), shows exactly that (literal translation means "The one who knows.") Russia, as well as many other cultures, produces tales with both encounters. These parts of folklore including omens, guardian spirits, and fate, all have little to do with the eastern orthodox religion yet seem to appear in much of the folklore of the 19th century. Visual omens, often in dreams, are well known including a gloved man indicating death, fish predicting marital luck, and children’s games foretelling marital life, fertility and even wars. Passed down are tales of how other indicators, include the crying of a baby that is not within sight, the hammering of nails off in the distance, and also ringing of the ears, can foretell different things.[8]

further references

- Lindquest, Galina. Conjuring Hope: Healing and Magic in Contemporary Russia. Vol. 1. New York: Berghahn Books, 2006.

- Pentikainen, Juha. "Marnina Takalo as an Individual." C. Jstor. 26 Feb. 2007.

- Pentikainen, Juha. "The Supernatural Experience." F. Jstor. 26 Feb. 2007.

- Worobec, Caroline. "Witchcraft Beliefs and Practices in Prerevolutionary Russia and Ukranian Villages." Jstor. 27 Feb. 2007.

Neopaganism

Modern practices identified by their practitioners as "witchcraft" have arisen in the twentieth century, which may be broadly subsumed under the heading of Neopaganism. However, as forms of Neopaganism can be quite different and have very different origins, these representations can vary considerably despite the shared name.

Wicca

During the 20th century interest in witchcraft in English-speaking and European countries began to increase, inspired particularly by Margaret Murray's theory of a pan-European witch-cult originally published in 1921, since discredited by further careful historical research.[9] Interest was intensified, however, by Gerald Gardner's claim in 1954 in Witchcraft Today that a form of witchcraft still existed in England. The truth of Gardner's claim is now disputed too, with different historians offering evidence for[10][11] or against[12][13] the religion's existence prior to Gardner.

The Wicca that Gardner initially taught was a witchcraft religion having a lot in common with Margaret Murray's hypothetically posited cult of the 1920s.[14] Indeed Murray wrote an introduction to Gardner's Witchcraft Today, in effect putting her stamp of approval on it. Wicca is now practiced as a religion of an initiatory secret society nature with positive ethical principles, organised into autonomous covens and led by a High Priesthood. Wiccan writings and ritual show borrowings from a number of sources including 19th and 20th century ceremonial magic, the medieval grimoire known as the Key of Solomon, Aleister Crowley's Ordo Templi Orientis and pre-Christian religions.[15][16][17] In Wicca, Samhain or Halloween is held to be the time when the veil between the living world and the Other World is at its thinnest, and this is a common time to attempt contact with those who have passed on. Both men and women are equally termed "witches." They practice a form of duotheistic universalism.

Since Gardner's death in 1964 the Wicca that he claimed he was initiated into has attracted many initiates, becoming the largest of the various witchcraft traditions in the Western world, and has influenced various occult movements and groups. In particular it has inspired a large movement of "Eclectic Wiccans" who are not initiated into the original lineage but have adopted similar practices and beliefs.

Judeo-Paganism

Some Neopagans study and practice forms of magery based on a syncretism between classical Jewish mysticism and modern witchcraft. (See "The Witches Qabalah", in the list of references below.) These practitioners tend to identify with Judeo-Paganism (also known as Jewish Paganism), and/or practice Jewitchery, or Jewish Witchcraft. These individuals and groups either borrow from existing Jewish magical traditions or reconstruct rituals based on Judaism and NeoPaganism. Several references on these subjects include Ellen Cannon Reed's book "The Witches Qabala: The Pagan Path and the Tree of Life", "The Hebrew Goddess", by Raphael Patai, and the forthcoming book "Magickal Judaism: Blending Pagan and Jewish Practice", by Jennifer Hunter.

Reconstructive

The basis of various historical forms of witchcraft find their roots in pre-Christian cultural practices. There has been a strong movement to recreate pre-Christian traditions where the old forms have been lost for various reasons, including practices such as Divination, Seid and various forms of Shamanism. There have been a number of pagan practitioners claiming inheritance to non-Gardnerian traditions as well.

Witches in popular culture

Movies

Many movies contain witches as a plot element for example Practical Magic, The Craft, Hocus Pocus, The Blair Witch Project, and Harry Potter. These movies generally include stereotypical use of Brooms, Wands, and Cauldrons.

Books

One of the most famous series, the Harry Potter books, are set in a world populated by Witches and Wizards.

Another rather popular series of books that deal with witches are the Sweep or Wicca series by Cate Tiernan. The series contains fourteen books and one novel that follow the story of Morgan Rowlands, a girl who finds out she is descended from a long line of witches. Along with Morgan, other characters develop their own role in Wicca, and relationships. The books deal with teen problems, and many teens can relate to the stories on countless levels.

Terry Pratchett's Discworld series also features witches significantly.

Recent history

Especially in media aimed at children (such as fairy tales), witches are often depicted as wicked old women with wrinkled skin and pointy hats, clothed in black or purple, with warts on their noses and sometimes long claw-like fingernails. Like the three "Weird Sisters" from Macbeth, they are often portrayed as concocting potions in large cauldrons. Witches typically ride through the air on a broomstick as in the Harry Potter universe or in more modern spoof versions, a vacuum cleaner as in the Hocus Pocus universe. One of the most famous recent depictions is the Wicked Witch of the West, from L. Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

See also

- Astrology, reading of horoscopes

- Auras

- Balthasar Bekker

- Catalan mythology about witches

- Divination - by tarot, runes, etc.

- Execution of Witches

- Healing

- Kalku

- List of fictional witches

- List of magical terms and traditions

- Lysa Hora (paranormal)

- Magician

- Meditation

- Osculum infame

- Paganism

- Poppets

- Scrying

- séances; using ouija boards

- Seid (shamanic magic)

- Shamanism

- Sorginak (Basque witches)

- Voodoo

- Walpurgis Night

- Warlock

- Wicca

- Witch doctor

- Wyrd

- Zar (religious custom)

Notes

- ^ For a book-length treatment, see Lara Apps and Andrew Gow, Male Witches in Early Modern Europe, Manchester University Press (2003), ISBN 0719057094. Conversely, for repeated use of the term "warlock" to refer to a male witch see Chambers, Robert, Domestic Annals of Scotland, Edinburgh, 1861; and Sinclair, George, Satan's Invisible World Discovered, Edinburgh, 1871.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, the Compact Edition, Oxford University Press, p. 2955, 1971

- ^ for instance, see Luck, Georg, Arcana Mundi: Magic and the Occult in the Greek and Roman Worlds; a Collection of Ancient Texts, Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1985, 2006; also Kittredge, G. L., Witchcraft in Old and New England, New York: Russell & Russell, 1929, 1957, 1958; and Davies, Owen, Witchcraft, Magic and Culture, 1736-1951, Manchester University Press, 1999

- ^ International Standard Bible Encyclopedia article on Witchcraft, last accessed 31 March 2006. There is some discrepancy between translations; compare with that given in the Catholic Encyclopedia article on Witchcraft (accessed 31 March 2006), and the L. W. King translation (accessed 31 March 2006)

- ^ I Samuel 28

- ^ Geister, Magier und Muslime. Dämonenwelt und Geisteraustreibung im Islam. Kornelius Hentschel, Diederichs 1997, Germany

- ^ Magic and Divination in Early Islam (The Formation of the Classical Islamic World) by Emilie Savage-Smith (Ed.), Ashgate Publishing 2004

- ^ See also Ryan, W.F. The Bathhouse at Midnight: An Historical Survey of Magic and Divination in Russia, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999

- ^ Rose, Elliot, A Razor for a Goat, University of Toronto Press, 1962. Hutton, Ronald, The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles, Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell Publishers, 1993. Hutton, Ronald, The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft, Oxford University Press, 1999

- ^ Heselton, Philip. Wiccan Roots.

- ^ Heselton, Philip. Gerald Gardner and the Cauldron of Inspiration.

- ^ Kelly, Aidan, "Crafting the Art of Magic," Llewellyn Publications, 1991

- ^ Hutton, Ronald, "Triumph of the Moon," Oxford University Press, 1999.

- ^ Murray, Margaret A., The Witch-Cult in Western Europe,Oxford University Press, 1921

- ^ Hutton, R.,The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft, Oxford University Press, pp. 205-252, 1999

- ^ Kelly, A.A., Crafting the Art of Magic, Book I: a History of Modern Witchcraft, 1939-1964, Minnesota: Llewellyn Publications, 1991

- ^ Valiente, D., The Rebirth of Witchcraft, London: Robert Hale, pp. 35-62, 1989

External links

- Bibliography for the Study of Magic Witchcraft and Religion, James Dow, Professor of Anthropology at Oakland University

- Some historical notes on the witch-craze from historian Trevor Roper

- Kabbalah On Witchcraft - A Jewish view (Audio) chabad.org

- Old Witchcraft by Bob Andrews

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Witchcraft

- Witchcraft in the Catholic Encyclopedia on (New Advent)

- Witchcraft and Devil Lore in the Channel Islands, 1886, by John Linwood Pitts, from Project Gutenberg

- A Treatise of Witchcraft, 1616, by Alexander Roberts, from Project Gutenberg

- The Witches' Voice 1997-2007 The Witches' Voice Inc

- [4] Traditional British witchcraft site.