Korean language

| Korean | |

|---|---|

| 한국어, 조선말 Hangugeo, Chosŏnmal | |

| Native to | South Korea, North Korea |

Native speakers | 78 million[1] |

Unclassified: perhaps an Altaic language or a language isolate | |

| Exclusive use of Hangul (N. & S. Korea), mix of Hangul and Hanja (S. Korea), or Cyrillic alphabet (lesser used in Goryeomal) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | S. Korea: Gungnip-gugeowon (National Institute of Korean Language; 국립국어원) N. Korea: Sahoe Kwahagwŏn Ŏhak Yŏnguso (사회 과학원 어학 연구소) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ko |

| ISO 639-2 | kor |

| ISO 639-3 | kor |

- This article is mainly about the spoken Korean language. See Hangul for details on the native Korean writing system.

Korean (한국어/조선말, see below) is the official language of both North Korea and South Korea. It is also one of the two official languages in the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture in China. There are about 80 million Korean speakers, with large groups in various Post-Soviet states, as well as in other diaspora populations in China, Australia, the United States, Canada, Brazil, Japan, and more recently, the Philippines.

The genealogical classification of the Korean language is debated. Many linguists place it in the Altaic language family, but some consider it to be a language isolate. It is agglutinative in its morphology and SOV in its syntax. Similar to the Japanese and Vietnamese languages, Korean language was influenced by the Chinese language in the form of Sino-Korean words. Native Korean words account for about 35% of the Korean vocabulary, while about 60% of the Korean vocabulary consists of Sino-Korean words. The remaining 5% comes from loan words from other languages, 90% of which are from English.[2]

Names

The Korean names for the language are based on the names for Korea used in North and South Korea.

In North Korea and Yanbian in China, the language is most often called Chosŏnmal (조선말; with Hanja: 朝鮮말), or more formally, Chosŏnŏ (조선어; 朝鮮語).

In the Republic of Korea, the language is most often called Hangungmal (한국말; 韓國말), or more formally, Hangugeo (한국어; 韓國語) or Gugeo (국어; 國語; literally "national language"). It is sometimes colloquially called Urimal ("our language"; 우리말 in one word in South Korea, 우리 말 with a space in North Korea).

On the other hand, Korean people in the former USSR, who refer to themselves as Koryo-saram (also Goryeoin [고려인; 高麗人; literally, "Goryeo person(s)"]) call the language Goryeomal (고려말; 高麗말).

Classification

The classification of the modern Korean language is uncertain, and due to the lack of any one generally accepted theory, it is sometimes described conservatively as a language isolate.

Since the publication of the article of Ramstedt in 1926, many linguists support the hypothesis that Korean can be classified as an Altaic language, or as a relative of proto-Altaic. Korean is similar to Altaic languages in that they both lack certain grammatical elements, including number, gender, articles, fusional morphology, voice, and relative pronouns (Kim Namkil). Korean especially bears some morphological resemblance to some languages of the Eastern Turkic group, namely Sakha (Yakut). Vinokurova, a scholar of the Sakha language, noted that like in Korean, and unlike in other Turkic languages or a variety of other languages surveyed, adverbs in Sakha are derived from verbs with the help of derivational morphology; however, she did not suggest this implied any relation between the two languages.[3]

It is also considered likely that Korean is related in some way to Japanese, since the two languages have a similar grammatical structure. Genetic relationships have been postulated both directly and indirectly, the latter either through placing both languages in the Altaic family, or by arguing for a relationship between Japanese and the Buyeo languages of Goguryeo and Baekje (see below); the proposed Baekje relationship is supported additionally by phonological similarities such as the general lack of consonant-final sounds, and by cognates such as Baekje mir, Japanese mi- "three".[4] Furthermore, there are known cultural links between Baekje and Japan; historical evidence shows that, in addition to playing a large role in the founding and growth of Yamato Japan, many of the Baekje upper classes, as well as the artisans and merchants, fled to Japan when the kingdom fell (which is corroborated by Japanese Emperor Akihito in a speech marking his 68th birthday).[5]

Others argue, however, that the similarities are not due to any genetic relationship, but rather to a sprachbund effect. See East Asian languages for morphological features shared among languages of the East Asian sprachbund, and Japanese language classification for further details on the possible relationship.

Of the ancient languages attested in the Korean Peninsula, modern Korean is believed to be a descendent of the languages of Samhan and Silla; it is unknown whether these are related to the Buyeo languages, though many Korean scholars believe they were mutually intelligible, and the collective basis of what in the Goryeo period would merge to become Middle Korean (the language before the changes that the Seven-Year War brought) and eventually Modern Korean. The Jeju dialect preserves some archaic features that can also be found in Middle Korean, whose arae a is retained in the dialect as a distinct vowel.

There are also fringe theories proposing various other relationships; for example, a few linguists such as Homer B. Hulbert have also tried to relate Korean to the Dravidian languages through the similar syntax in both.[6]

Dialects

Korean has several dialects (called mal [literally "speech"], saturi, or bang-eon in Korean). The standard language (pyojuneo or pyojunmal) of South Korea is based on the dialect of the area around Seoul, and the standard for North Korea is based on the dialect spoken around P'yŏngyang. These dialects are similar, and are in fact all mutually intelligible, perhaps with the exception of the dialect of Jeju Island (see Jeju Dialect). The dialect spoken in Jeju is in fact classified as a different language by some Korean linguists. One of the most notable differences between dialects is the use of stress: speakers of Seoul dialect use stress very little, and standard South Korean has a very flat intonation; on the other hand, speakers of the Gyeongsang dialect have a very pronounced intonation.

It is also worth noting that there is substantial evidence for a history of extensive dialect levelling, or even convergent evolution or intermixture of two or more originally distinct linguistic stocks, within the Korean language and its dialects. Many Korean dialects have basic vocabulary that is etymologically distinct from vocabulary of identical meaning in Standard Korean or other dialects, such as South Jeolla dialect /kur/ vs. Standard Korean /ip/ "mouth" or Gyeongsang dialect /ʨʌŋ.gu.ʥi/ vs. Standard Korean /puːʨʰu/ "garlic chives." This suggests that the Korean Peninsula may have at one time been much more linguistically diverse than it is at present.[citation needed] See also the Buyeo languages hypothesis.

There is a very close connection between the dialects of Korean and the regions of Korea, since the boundaries of both are largely determined by mountains and seas. Here is a list of traditional dialect names and locations:

| Standard dialect | Where used |

|---|---|

| Seoul | Seoul (서울), Incheon (인천), Gyeonggi (경기) |

| P'yŏngan (평양) | P'yŏngyang, P'yŏngan region, Chagang (North Korea) |

| Regional dialect | Where used |

| Gyeonggi | some of Gyeonggi region (South Korea) |

| Chungcheong | Daejeon, Chungcheong region (South Korea) |

| Gangwon | Gangwon-do (South Korea)/Kangwŏn (North Korea) |

| Gyeongsang | Busan, Daegu, Ulsan, Gyeongsang region (South Korea) |

| Hamgyŏng | Rasŏn, Hamgyŏng region, Ryanggang (North Korea) |

| Hwanghae | Hwanghae region (North Korea) |

| Jeju | Jeju Island/Province (South Korea) |

| Jeolla | Gwangju, Jeolla region (South Korea) |

Phonology

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | ㅁ /m/ | ㄴ /n/ | ㅇ /ŋ/ (syllable-final) | |||

| Plosive and Affricate |

plain | ㅂ /p/ | ㄷ /t/ | ㅈ /ʨ/ | ㄱ /k/ | |

| tense | ㅃ /p͈/ | ㄸ /t͈/ | ㅉ /ʨ͈/ | ㄲ /k͈/ | ||

| aspirated | ㅍ /pʰ/ | ㅌ /tʰ/ | ㅊ /ʨʰ/ | ㅋ /kʰ/ | ||

| Fricative | plain | ㅅ /s/ | ㅎ /h/ | |||

| tense | ㅆ /s͈/ | |||||

| Liquid | ㄹ /l/ | |||||

The IPA symbol <͈> (a subscript double straight quotation mark) is used to denote the tensed consonants /p͈/, /t͈/, /k͈/, /ʨ͈/, /s͈/. Its official use in the Extended IPA is for 'strong' articulation, but is used in the literature for faucalized voice. The Korean consonants also have elements of stiff voice, but it is not yet known how typical this is of faucalized consonants. They are produced with a partially constricted glottis and additional subglottal pressure in addition to tense vocal tract walls, laryngeal lowering, or other expansion of the larynx.

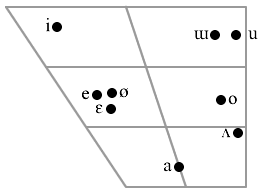

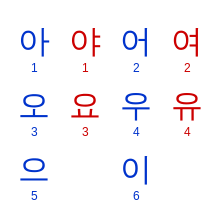

Vowels

|

|

|

| Monophthongs | /i/ ㅣ, /e/ ㅔ, /ɛ/ ㅐ, /a/ ㅏ, /o/ ㅗ, /u/ ㅜ, /ʌ/ ㅓ, /ɯ/ ㅡ, /ø/ ㅚ |

|---|---|

| Vowels preceded by intermediaries, or Diphthongs |

/je/ ㅖ, /jɛ/ ㅒ, /ja/ ㅑ, /wi/ ㅟ, /we/ ㅞ, /wɛ/ ㅙ, /wa/ ㅘ, /ɯi/ ㅢ, /jo/ ㅛ, /ju/ ㅠ, /jʌ/ ㅕ, /wʌ/ ㅝ |

Phonology

/s/ becomes an alveolo-palatal [ɕ] before [j] or [i] for most speakers (but see Differences in the language between North Korea and South Korea). This occurs with the tense fricative and all the affricates as well. At the end of a syllable, /s/ changes to /t/ (Example: beoseot (버섯) 'mushroom').

/h/ may become a bilabial [ɸ] before [o] or [u], a palatal [ç] before [j] or [i], a velar [x] before [ɯ], a voiced [ɦ] between voiced sounds, and a [h] elsewhere.[citation needed]

/p, t, ʨ, k/ become voiced [b, d, ʥ, g] between voiced sounds.

/l/ becomes alveolar flap [ɾ] between vowels, and [l] or [ɭ] at the end of a syllable or next to another /l/. Note that a written syllable-final 'ㄹ', when followed by a vowel or a glide (i.e., when the next character starts with 'ㅇ'), migrates to the next syllable and thus becomes [ɾ].

Traditionally, /l/ was disallowed at the beginning of a word. It disappeared before [j], and otherwise became /n/. However, the inflow of western loanword changed the trend, and now word-initial /l/ (mostly from English loanwords) are pronounced as a free variation of either [ɾ] or [l]. The traditional prohibition of word-initial /l/ became a morphological rule called "initial law" (두음법칙) in South Korea, which pertains to Sino-Korean vocabulary. Such words retain their word-initial /l/ in North Korea.

All obstruents (plosives, affricates, fricatives) are unreleased [p̚, t̚, k̚] at the end of a word.

Plosive stops /p, t, k/ become nasal stops [m, n, ŋ] before nasal stops.

Hangul spelling does not reflect these assimilatory pronunciation rules, but rather maintains the underlying morphology.

One difference between the pronunciation standards of North and South Korea is the treatment of initial [r], and initial [n]. For example,

- "labour" - north: rodong (로동), south: nodong (노동)

- "history" - north: ryŏksa (력사), south: yeoksa (역사)

- "female" - north: nyŏja (녀자), south: yeoja (여자)

Grammar

Sentence structure

Korean is an agglutinative language. Modifiers precede the modified word. The basic form of a Korean sentence is Subject Object Verb, but the verb is the only required and immovable element.

- A: "가게에 가세요?" (gage-e gaseyo?)

- B: "네." (ne.)

Literal translation:

- A: *"store+[location marker] go+[polite interrogative marker]?"

- B: "Yes."

English equivalent:

- A: "Are [you] going to the store?"

- B: "Yes."

Parts of speech

Verb

Korean verbs (동사, dongsa, 動詞) are also known in English as "action verbs" or "dynamic verbs" to distinguish them from (형용사, hyeong-yongsa, "adjectives"), which are also known as "descriptive verbs" or "stative verbs".

Examples include 하다 (hada, "to do, to have") and 가다 (gada, "to go"). For a larger list of Korean verbs, see wikt:Category:Korean verbs.

Unlike most European languages, Korean does not conjugate verbs using agreement with the subject, and nouns have no gender. Instead, verb conjugations depend upon the verb tense, aspect, mood, and the social relation between the speaker, the subjects, and the listeners. The system of speech levels and honorifics loosely resembles the T-V distinction of most Indo-European languages. For example, different endings are used based on whether the subjects and listeners are friends, parents, or honoured persons.

Adjective

Words categorized as Korean adjectives (형용사, hyeong-yongsa, 形容詞) conjugate similarly to verbs, so some English texts call them "descriptive verbs" or "stative verbs", but they are distinctly separate from 동사 (dongsa).

English does not have an identical grammatical category, so the English translation of Korean adjectives may misleadingly suggest that they are verbs. For example, 붉다 (bukda) translates literally as "to be red" and 아쉽다 (aswipda) often best translates as "to miss", but both are 형용사 (hyeong-yongsa, "adjectives"). For a larger list of Korean adjectives, see wikt:Category:Korean adjectives.

Determiner

Korean determiners (관형사, gwanhyeongsa) are also known in English as "determinatives", "adnominals", "pre-nouns", "attributives", and "unconjugated adjectives". Examples include 각 (gak, "each") and 느린 (neurin). For a larger list, see wikt:Category:Korean determiners.

Noun

Korean nouns (명사, myeongsa) are also known in English as "substantives". Examples include 가족 (gajok, "household") and 맛 (mat, "flavor"). For a larger list, see wikt:Category:Korean nouns.

Pronoun

Korean pronouns (대명사, daemyeongsa) include 나 (na, "I") and 그 (geu). For a larger list, see wikt:Category:Korean pronouns.

Adverb

Korean adverbs (부사, busa) include 또 (tto, "also") and 가득 (gadeuk, "fully"). For a larger list, see wikt:Category:Korean adverbs.

Particle

Korean particles (조사, josa) are also known in English as "postpositions". Examples include 는 (neun, topic marker) and 를 (reul, object marker). For a larger list, see wikt:Category:Korean particles. wikt:Category:Korean particles

Interjection

Korean interjections (감탄사, gamtansa) are also known in English as "exclamations". Examples include 아니 (ani, "no"). For a larger list, see wikt:Category:Korean interjections.

Number

Korean numbers (수사, susa) are also known in English as "numerals".

Speech levels and honorifics

The relationship between a speaker or writer and his or her subject and audience is paramount in Korean, and the grammar reflects this. The relationship between speaker/writer and subject referent is reflected in honorifics, while that between speaker/writer and audience is reflected in speech level.

Honorifics

When talking about someone superior in status, a speaker or writer usually uses special nouns or verb endings to indicate the subject's superiority. Generally, someone is superior in status if he/she is an older relative, a stranger of roughly equal or greater age, or an employer, teacher, customer, or the like. Someone is equal or inferior in status if he/she is a younger stranger, student, employee or the like.

Speech levels

There are no fewer than 7 verb paradigms or speech levels in Korean, and each level has its own unique set of verb endings which are used to indicate the level of formality of a situation. Unlike "honorifics" — which are used to show respect towards the referent of a subject — speech levels are used to show respect towards a speaker's or writer's audience. The names of the 7 levels are derived from the non-honorific imperative form of the verb 하다 (hada, "do") in each level, plus the suffix 체 ('che', Hanja: 體), which means "style."

The highest 5 levels use final verb endings and are generally grouped together as jondaemal (존대말), while the lowest 2 levels (해요체 haeyoche and 해체 haeche) use non-final endings and are called 반말 (banmal, "half-words") in Korean. (The haeyoche in turn is formed by simply adding the non-final ending -요 (-yo) to the haeche form of the verb.)

Vocabulary

The core of the Korean vocabulary is made up of native Korean words. More than 50% of the vocabulary (up to 70% by some estimates), however, especially scholarly terminology, are Sino-Korean words[citation needed], either

- directly borrowed from Written Chinese, or

- coined in Japan or Korea using Chinese characters.

Korean has two number systems: one native, and one borrowed from the Chinese.

To a much lesser extent, words have also occasionally been borrowed from Mongolian, Sanskrit, and other languages. Conversely, the Korean language itself has also contributed some loanwords to other languages, most notably the Tsushima dialect of Japanese.

In modern times, many words have been borrowed from Japanese and Western languages such as German (areubaiteu ‘part-time job’, allereugi ‘allergy’) and more recently English. Concerning daily usage vocabulary except what can be written in hanja, more words have possibly been borrowed from English than from any other language. Some Western words were borrowed indirectly via Japanese, taking a Japanese sound pattern, for example ‘dozen’ > ダース dāsu > 다스 daseu. Most indirect Western borrowings are now written according to current hangulization rules for the respective Western language, as if borrowed directly. There are a few more complicated borrowings such as ‘German(y)’ (see Names for Germany), the first part of whose endonym [ˈd̥ɔɪ̯ʧʷ.la̠ntʰ] the Japanese approximated using the Kanji 獨逸 doitsu that were then accepted into the Korean language by their Sino-Korean pronunciation: 獨 dok + 逸 il = Dogil. In South Korean official use, a number of other Sino-Korean country names have been replaced with phonetically oriented hangulizations of the countries' endonyms or English names.

North Korean vocabulary shows a tendency to prefer native Korean over Sino-Korean or foreign borrowings, especially with recent political objectives aimed at eliminating foreign (mostly Chinese) influences on the Korean language in the North. By contrast, South Korean may have several Sino-Korean or foreign borrowings which tend to be absent in North Korean.

Writing system

|

| Korean writing systems |

|---|

| Hangul |

|

| Hanja |

| Mixed script |

| Braille |

| Transcription |

| Transliteration |

In ancient times, the languages of the Korean peninsula were written using Chinese characters, using hyangchal or idu. Knowledge of such systems were lost, and the Korean language was not written at all; the aristocracy used Classical Chinese for its writing.

Korean is now mainly written in Hangul, the Korean alphabet, optionally mixing in Hanja to write Sino-Korean words. South Korea still teaches 1800 Hanja characters in its schools, while the North abolished the use of hanja decades ago.

Below is a chart of the Korean alphabet's symbols and their canonical IPA values:

| Hangul | ㅂ | ㄷ | ㅈ | ㄱ | ㅃ | ㄸ | ㅉ | ㄲ | ㅍ | ㅌ | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅅ | ㅎ | ㅆ | ㅁ | ㄴ | ㅇ | ㄹ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | b,p | d,t | j | g,k | pp | tt | jj | kk | p | t | ch | k | s | h | ss | m | n | ng | r,l | ||

| IPA | p | t | ʨ | k | p͈ | t͈ | ʨ͈ | k͈ | pʰ | tʰ | ʨʰ | kʰ | s | h | s͈ | m | n | ŋ | w | r | j |

| Hangul | ㅣ | ㅔ | ㅐ | ㅏ | ㅗ | ㅜ | ㅓ | ㅡ | ㅢ | ㅖ | ㅒ | ㅑ | ㅛ | ㅠ | ㅕ | ㅟ | ㅞ | ㅙ | ㅘ | ㅝ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | i | e | ae | a | o | u | eo | eu | ui | ye | yae | ya | yo | yu | yeo | wi | we | wae | wa | wo |

| IPA | i | e | ɛ | a | o | u | ʌ | ɯ | ɰi | je | jɛ | ja | jo | ju | jʌ | wi | we | wɛ | wa | wʌ |

Modern Korean is written with spaces between words, a feature not found in Chinese or Japanese. Korean punctuation marks are almost identical to Western ones. Traditionally, Korean was written in columns from top to bottom, right to left, but is now usually written in rows from left to right, top to bottom.

Differences between North Korea and South Korea

The Korean language used in the North and the South exhibits differences in pronunciation, spelling, grammar and vocabulary.[7]

Pronunciation

In North Korea, palatalization of /si/ is optional, and /ʨ/ can be pronounced as [z] in between vowels.

Words that are written the same way may be pronounced differently, such as the examples below. The pronunciations below are given in Revised Romanization, McCune-Reischauer and Hangul, the last of which represents what the Hangul would be if one writes the word as pronounced.

| Word | Meaning | Pronunciation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North (RR/MR) | North (Hangul) | South (RR/MR) | South (Hangul) | ||

| 넓다 | wide | neoptta (nŏpta) | 넙따 | neoltta (nŏlta) | 널따 |

| 읽고 | to read (continuative form) |

ilkko (ilko) | 일꼬 | ilkko (ilko) | 일꼬 |

| 압록강 | Amnok River | amrokgang (amrokkang) | 암록강 | amnokkang (amnokkang) | 암녹깡 |

| 독립 | independence | dongrip (tongrip) | 동립 | dongnip (tongnip) | 동닙 |

| 관념 | idea / sense / conception | gwallyeom (kwallyŏm) | 괄렴 | gwannyeom (kwannyŏm) | 관념 |

| 혁신적* | innovative | hyeoksinjeok (hyŏksinchŏk) | 혁씬쩍 | hyeoksinjeok (hyŏksinjŏk) | 혁씬적 |

* Similar pronunciation is used in the North whenever the hanja "的" is attached to a Sino-Korean word ending in ㄴ, ㅁ or ㅇ. (In the South, this rule only applies when it is attached to any single-character Sino-Korean word.)

Spelling

Some words are spelt differently by the North and the South, but the pronunciations are the same.

| Word spelling | Meaning | Pronunciation (RR/MR) | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | South | |||

| 해빛 | 햇빛 | sunshine | haetbit (haetpit) | The "sai siot" ('ㅅ' used for indicating sound change) is almost never written out in the North. |

| 벗꽃 | 벚꽃 | cherry blossom | beotkkot (pŏtkkot) | |

| 못읽다 | 못 읽다 | cannot read | monnikda (monnikta) | Spacing. |

| 한나산 | 한라산 | Hallasan | hallasan (hallasan) | When a ㄴ-ㄴ combination is pronounced as ll, the original Hangul spelling is kept in the North, while the Hangul is changed in the South. |

| 규률 | 규율 | rules | gyuyul (kyuyul) | In words where the original hanja is spelt "렬" or "률" and follows a vowel, the initial ㄹ is not pronounced in the North, making the pronunciation identical with that in the South where the ㄹ is dropped in the spelling. |

Spelling and pronunciation

Some words have different spellings and pronunciations in the North and the South, some of which were given in the "Phonology" section above:

| Word | Meaning | Remarks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North spelling | North pronun. | South spelling | South pronun. | ||

| 력량 | ryeongryang (ryŏngryang) | 역량 | yeongnyang (yŏngnyang) | strength | Korean words originally starting in r or n have their r or n dropped in the South Korean version if the sound following it is an i or y sound. |

| 로동 | rodong (rodong) | 노동 | nodong (nodong) | work | Korean words originally starting in r have their r changed to n in the South Korean version if the sound following it is a sound other than i or y. |

| 원쑤 | wonssu (wŏnssu) | 원수 | wonsu (wŏnsu) | enemy | "Enemy" and "head of state" are homophones in the South. Possibly to avoid referring to Kim Il-sung / Kim Jong-il as the enemy, the second syllable of "enemy" is written and pronounced 쑤 in the North. |

| 라지오 | rajio (rajio) | 라디오 | radio (radio) | radio | |

| 우 | u (u) | 위 | wi (wi) | on; above | |

| 안해 | anhae (anhae) | 아내 | anae (anae) | wife | |

| 꾸바 | kkuba (kkuba) | 쿠바 | kuba (k'uba) | Cuba | When transcribing foreign words from languages that do not have contrasts between aspirated and unaspirated stops, North Koreans generally use tensed stops for the unaspirated ones while South Koreans use aspirated stops in both cases. |

| 페 | pe (p'e) | 폐 | pye (p'ye), pe (p'e) | lungs | All hanja pronounced as pye (p'ye) or pe (p'e) in the South are pronounced as pe (p'e) in the North. The spelling is also accordingly different. |

In general, when transcribing place names, North Korea tends to use the pronunciation in the original language more than South Korea, which often uses the pronunciation in English. For example:

| Original name | North Korea transliteration | English name | South Korea transliteration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spelling | Pronunciation | Spelling | Pronunciaton | ||

| Ulaanbaatar | 울란바따르 | ullanbattareu (ullanbattarŭ) | Ulan Bator | 울란바토르 | ullanbatoreu (ullanbat'orŭ) |

| København | 쾨뻰하븐 | koeppenhabeun (k'oeppenhabŭn) | Copenhagen | 코펜하겐 | kopenhagen (k'op'enhagen) |

| al-Qāhirah | 까히라 | kkahira (kkahira) | Cairo | 카이로 | kairo (k'airo) |

Grammar

Some grammatical constructions are also different:

| Word | Meaning | Remarks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North spelling | North pronun. | South spelling | South pronun. | ||

| 되였다 | doeyeotda (toeyŏtta) | 되었다 | doeeotda (toeŏtta) | past tense of 되다 (doeda/toeda), "to become" | All similar grammar forms of verbs or adjectives that end in ㅣ in the stem (i.e. ㅣ, ㅐ, ㅔ, ㅚ, ㅟ and ㅢ) in the North use 여 instead of the South's 어. |

| 고마와요 | gomawayo (komawayo) | 고마워요 | gomawoyo (komawŏyo) | thanks | ㅂ-irregular verbs in the North use 와 (wa) for all those with a positive ending vowel; this only happens in the South if the verb stem has only one syllable. |

| 할가요 | halgayo (halkayo) | 할까요 | halkkayo (halkkayo) | Shall we do? | Although the hangul differ, the pronunciations are the same (i.e. with the tensed ㄲ sound). |

Vocabulary

Some vocabulary is different between the North and the South:

| Word | Meaning | Remarks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North spelling | North pronun. | South spelling | South pronun. | ||

| 문화주택 | munhwajutaek (munhwajut'aek) | 아파트 | apateu (ap'at'ŭ) | Apartment | 아빠트 (appateu/appat'ŭ) is also used in the North. |

| 조선말 | joseonmal (chosŏnmal) | 한국어 | han-gugeo(han'gugeo) | Korean language | |

| 곽밥 | gwakbap (kwakpap) | 도시락 | dosirak (tosirak) | lunch box | |

Others

In the North, 《 and 》 are the symbols used for quotes; in the South, quotation marks equivalent to the English ones, “ and ”, are standard, although 『 』 and 「 」 are sometimes used in popular novels.

See also

- Hangul

- Korean romanization

- Korean numerals

- Korean count word

- Korean language and computers

- Hanja

- Sino-Korean

- Korean with mixed script of Hangul and Hanja

- List of English words of Korean origin

- Altaic hypothesis

- List of Korea-related topics

- Korean profanity

References

- ^ "Korean". ethnologue. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- ^ Sohn, Ho-Min. The Korean Language (Section 1.5.3 "Korean vocabulary", p.12-13), Cambridge University Press, 2001. ISBN 0521369436

- ^ Vinokurova, Nadya (1999-04-08). "The Typology of Adverbial Agreement" (Microsoft Word). Retrieved 2007-01-15.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Beckwith, Christopher I. (2004). Koguryo, The Language Of Japan's Continental Relatives: the language of Japan's continental. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 9004139494.

- ^ Watts, Jonathan (2001-12-28). "The emperor's new roots". The Guardian. Retrieved 2007-05-11.

- ^ Hulbert, Homer (1900). "Korea's Geographical Significance". Journal of the American Geographical Society of New York. 32 (4): 322–327. doi:10.2307/197061.

- ^ Kanno, Hiroomi (ed.) / Society for Korean Linguistics in Japan (1987). Chōsengo o manabō (『朝鮮語を学ぼう』), Sanshūsha, Tokyo. ISBN 4-384-01506-2

Bibliography

- Sohn, H.-M. (1999). The Korean Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Song, J.J. (2005). The Korean Language: Structure, Use and Context. London: Routledge.