Korean Air Lines Flight 007

Artist's rendition of HL7442, the KAL 747 lost during Flight 007 | |

| Occurrence | |

|---|---|

| Date | 1 September 1983 |

| Summary | Airliner shot down |

| Site | Strait of Tartary, West of Sakhalin Island 46°34′N 141°17′E / 46.567°N 141.283°E |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 747-230B |

| Operator | Korean Air Lines |

| Registration | HL7442 (previously D-ABYH) |

| Flight origin | John F. Kennedy International Airport New York City, New York United States |

| Last stopover | Anchorage International Airport Anchorage, Alaska United States |

| Destination | Gimpo International Airport, Seoul South Korea |

| Passengers | 246[1] |

| Crew | 23[Notes 1] |

| Fatalities | 269 |

| Survivors | 0 |

Korean Air Lines Flight 007 (KAL 007, KE 007[Notes 2]) was a Korean Air Lines civilian airliner that was shot down by Soviet jet interceptors on September 1, 1983 over the Sea of Japan, just west of Sakhalin island over prohibited Soviet airspace. All 269 passengers and crew aboard were killed, including Lawrence McDonald, a sitting member of the United States Congress. The aircraft was en route from New York City via Anchorage to Seoul, when it strayed into prohibited Soviet airspace due to a navigational error.

The Soviet Union initially denied knowledge of the incident,[2] but later admitted shooting the aircraft down, claiming that it was on a spy mission.[3] The Politburo believed it was a deliberate provocation by the United States,[4] to test the U.S.S.R.'s military preparedness, or even to provoke a war. The United States accused the Soviet Union of obstructing search and rescue operations[5]. Furthermore, the Soviet military suppressed evidence sought by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) investigation, notably the flight data recorders,[6] which were eventually released nine years later after a change of government.[7]

The incident was one of the tensest moments of the Cold War, and resulted in an escalation of anti-Soviet sentiment, particularly in the United States. The opposing points of view on the incident were never fully resolved; consequently, several groups continue to dispute official reports and offer alternate theories of the event. The subsequent release of transcripts and flight recorders by the Russian Federation has addressed some details.

As a result of the incident, the United States altered tracking procedures for aircraft departing Alaska, while the interface of the autopilot used on airliners was redesigned to make it more failsafe.[8] President Ronald Reagan ordered the U.S. military to make the Global Positioning System (GPS) available for civilian use so that navigational errors like that of KAL 007 could be averted in the future.

Details of the flight

Korean Air Lines Flight 007 was a commercial Boeing 747-230B (Serial Number CN20559/186, registration: HL7442, formerly D-ABYH[9] operated by Condor Airlines) flying from New York City, United States to Seoul, South Korea. The aircraft departed Gate 15, 35 minutes behind its scheduled departure time of 23:50 EDT on August 30, 1983 (03:50 GMT, August 31). Carrying 246 passengers and 23 crew members,[Notes 1][10] the aircraft took off from John F. Kennedy International Airport. After refueling at Anchorage International Airport in Anchorage, Alaska, the aircraft, piloted on this leg of the journey by Captain Chun Byung-in,[11] departed for Seoul at 13:00 UTC (4:00 AM Alaska Time) on August 31, 1983.

The nationalities of the passengers were as follows: [12]

| Nationality | Victims |

|---|---|

| 2 | |

| 8 | |

| 1 | |

| 12 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 28 | |

| 76 passengers 23 active crew 6 deadheading crew | |

| 1 | |

| 16 | |

| 1 | |

| 23 | |

| 5 | |

| 2 | |

| 62 | |

| 1 | |

| Total | 269 |

The aircrew, 6 of whom were deadheading crew, consisted of 14 women and 12 men. Twelve passengers occupied the upper deck first class, while in business almost all of 24 seats were taken; in economy class, approximately 80 seats did not contain passengers. There were 22 children under the age of 12 aboard. U.S. congressman Lawrence McDonald from Georgia, who at the time was also the second president of the conservative John Birch Society, was on the flight. One hundred thirty passengers planned to connect to other destinations such as Tokyo, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.[13] Senator Jesse Helms of North Carolina, Senator Steven Symms of Idaho, and Representative Carroll J. Hubbard, Jr. of Kentucky were aboard sister flight KAL 015, which flew 15 minutes behind KAL 007; they were headed to Seoul, Korea in order to attend the ceremonies for the 30 year anniversary of the U.S.-Korea Mutual Defense Treaty. (Photos of passengers[14])

Flight deviation from assigned route

After taking off from Anchorage, the aircraft turned left, seeking its assigned Jet Route 501 (J501), which would take it over the navigational beacon at Bethel. Here, the aircraft would enter the northernmost of five 50-mile (80 km) wide airways, known as the NOPAC (North Pacific) routes, that bridge the Alaskan and Japanese coasts. KAL 007's particular airway, R-20 ("Romeo 20"), passes just 17.5 miles (28.2 km) from Soviet airspace off the Kamchatka coast.

The navigation systems installed in commercial aircraft at the time could operate in two different modes,[Notes 3] each of which was required during different phases of the flight: inertial navigation (INS) mode, where the aircraft follows a set of pre-programmed waypoints, and HEADING mode, where the autopilot flies an aircraft along a constant magnetic heading.[Notes 4]

The Anchorage VOR beacon was not operational due to maintenance.[15] The crew received a NOTAM (Notice to Airmen) of this fact, which was not seen as a problem as the captain could still check his position at the next VOR beacon at Bethel, 346 miles (557 km) away. However the aircraft had to navigate on a magnetic heading to the Bethel beacon, before it could start using INS mode to follow the waypoints comprising route Romeo-20 around the coast of the U.S.S.R. to Seoul. Since this leg was undertaken in the dark, pilotage could not assist the crew in navigating the route.

At about 10 minutes after take-off, KAL 007, flying on a heading of 245 degrees, began to deviate to the right (north) of its assigned route to Bethel; it would continue to fly on this constant heading for the next five and a half hours.[16]

International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) simulation and analysis of the flight data recorder determined that this deviation was probably caused by the aircraft's navigation system operating in HEADING mode, after the point that it should have switched to INS mode.[8][17] According to the ICAO, the autopilot was not operating in INS mode for one of two reasons. Either the crew did not switch the autopilot to INS mode (shortly after Cairn Mountain) or they selected the INS mode, but it did not activate as the aircraft had already deviated off track by more than the 7.5 nautical miles (13.9 km) tolerance permitted by the inertial navigation computer. In both scenarios, the autopilot remained in HEADING mode, and the problem was not detected by the crew.[8]

At 28 minutes after take-off, civilian radar at Kenai, on the eastern shore of Cook Inlet and with radar coverage 175 miles (282 km) west of Anchorage, tracked KAL 007 5.6 miles (9.0 km) north of where it should have been.[18]

When KAL 007 did not reach Bethel at 50 minutes after takeoff, military radar at King Salmon, Alaska, tracked KAL 007 at 12.6 nautical miles (23.3 km) north of where it should have been. However, there is no evidence to indicate that civil air traffic controllers or military radar personnel at Elmendorf Air Force Base (who were in a position to receive the King Salmon radar output), were aware of KAL 007's deviation in real-time, and therefore able to warn the aircraft. It had exceeded its permissible leeway of deviation sixfold, 2 nautical miles (3.7 km) of error being the maximum expected drift from course if the inertial navigation system was activated.[18]

KAL 007's divergence prevented the aircraft from transmitting its position via shorter range very high frequency radio (VHF). It therefore requested KAL 015, also en route to Seoul, to relay reports to air traffic control on its behalf.[19] KAL 007 requested KAL 015 to relay its position three times in total. At 14:43 GMT, KAL 007 directly transmitted a change of estimated time of arrival for its next waypoint, NEEVA, to the international flight service station at Anchorage,[20] but it did so over the longer range high frequency radio (HF) rather than VHF. HF transmissions are able to carry a longer distance than VHF, but are vulnerable to interference and static; VHF are clearer with less interference, and preferred by flight crews. The inability to establish direct radio communications to be able to transmit their position directly did not alert the pilots of KAL 007 of their ever increasing divergence[18] and was not considered unusual by air traffic controllers.[19] Halfway between Bethel and waypoint NABIE, KAL 007 passed through the southern portion of the North American Air Defense buffer zone. This zone, monitored intensively by National Security Agency assets, is north of Romeo 20 and off-limits to civilian aircraft.

KAL 007 continued its journey, ever increasing its deviation—60 nautical miles (110 km) off course at waypoint NABIE, 100 nautical miles (190 km) off course at waypoint NUKKS, and 160 nautical miles (300 km) off course at waypoint NEEVA—until it reached the Kamchatka Peninsula.[12]

| Airway R20 Waypoint | Co-ordinates | ATC | KAL 007 Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAIRN MOUNTAIN | 61°09′33″N 155°19′41″W / 61.1592°N 155.328°W | Anchorage | 5.6 miles (9.0 km) |

| BETHEL | 60°47′32″N 161°45′21″W / 60.79222°N 161.75583°W | Anchorage | 12.6 nautical miles (23.3 km) |

| NABIE | 59°18.0′N 171°45.4′W / 59.3000°N 171.7567°W | Anchorage | 60 nautical miles (110 km) |

| NUKKS | 57°15′N 179°44.3′E / 57.250°N 179.7383°E | Anchorage | 100 nautical miles (190 km) |

| NEEVA | 54°40.7′N 172°11.8′E / 54.6783°N 172.1967°E | Anchorage | 160 nautical miles (300 km) |

| NINNO | 52°21.5′N 165°22.8′E / 52.3583°N 165.3800°E | Anchorage | |

| NIPPI | 49°41.9′N 159°19.3′E / 49.6983°N 159.3217°E | Anchorage/Tokyo | 180 miles (290 km)[21] |

| NYTIM | 46°11.9′N 153°00.5′E / 46.1983°N 153.0083°E | Tokyo | 500 nautical miles (930 km) from point of impact |

| NOKKA | 42°23.3′N 147°28.8′E / 42.3883°N 147.4800°E | Tokyo | 350 nautical miles (650 km) from point of impact |

| NOHO | 40°25.0′N 145°00.0′E / 40.4167°N 145.0000°E | Tokyo | 390 nautical miles (720 km) from point of impact |

Shootdown

In 1983, Cold War tensions had escalated due to several factors: These included the United States's Strategic Defence Initiative, its deployment of Pershing II missiles in Europe and in April, FleetEx '83, the largest fleet exercise held to date in the North Pacific.[22][23] On the Soviet side, Operation RYAN was expanded.[24] United States Navy reconnaissance aircraft had repeatedly penetrated Soviet airspace during FleetEx '83, resulting in the dismissal or reprimanding of Soviet military officials who had been unable to shoot them down.[24] Lastly, there was a heightened alert around the Kamchatka Peninsula when KAL 007 was in the vicinity, due to a Soviet missile test that was scheduled for the same day. The missile test was the reason that a United States Air Force RC-135 reconnaissance aircraft was patrolling off the peninsula.[25]

When the Korean jetliner was about 80 miles (130 km) from the Kamchatka coast, four MiG-23 fighters were scrambled to intercept the fast and high-flying Boeing 747.[8] At 15:51 GMT, according to Soviet sources,[18] KAL 007 entered the restricted airspace of Kamchatka Peninsula. The buffer zone extended 200 kilometres (120 mi) from Kamchatka's coast and is known as a Flight Information Region (FIR). The 100 kilometres (62 mi) radius of the buffer zone nearest to Soviet territory had the additional designation of prohibited airspace. Significant command and control problems were experienced trying to vector the military jets onto the Boeing before they ran out of fuel. In addition, pursuit was made more difficult, according to Soviet Air Force Captain Alexander Zuyev, who defected to the West in 1989, because Arctic gales had knocked out Soviet radar ten days before.[26] The unidentified jetliner therefore crossed over the Kamchatka Peninsula back into international airspace over the Sea of Okhotsk without being intercepted.

Soviet Air Defence Force units that had been tracking the Korean aircraft for more than an hour while it entered and left Soviet airspace now classified the aircraft as a military target when it re-entered their airspace over Sakhalin Island.[8] After a protracted ground-controlled interception, three Su-15 Flagon fighters from nearby Dolinsk-Sokol airbase and a MiG-23[27]from Smirnykh Air Base managed to make visual contact with the Boeing. The pilot of the lead Su-15 fighter fired warning shots, but recalled later in 1991:[28]

I fired four bursts, more than 200 rounds. For all the good it did. After all, I was loaded with armour piercing shells, not incendiary shells. It's doubtful whether anyone could see them...

At this point, KAL 007 contacted Tokyo air traffic control requesting clearance to ascend to a higher flight level for reasons of fuel economy; the requested was granted, so the Boeing started to climb, gradually slowing as it exchanged speed for altitude. The decrease in speed caused the pursuing fighter to overshoot the Boeing, an action that was interpreted by the Soviet pilot as an evasive maneuver. The order to shoot KAL 007 down was given as it was about to leave Soviet airspace for the second time. At around 18:26 GMT, under pressure from ground controllers not to let the aircraft escape into international airspace, the lead fighter was able to move back into a position where it could fire two Kaliningrad K-8 air-to-air missiles at the intruder.[29]

Soviet pilot's recollection of shootdown

In a 1991 interview with Izvestia, Major Gennadie Osipovich, pilot of the Su-15 interceptor that shot the Boeing down, spoke about his recollections of the events leading up to the shootdown. He recalled telling ground controllers that, contrary to official Soviet statements at the time, there were blinking lights, which he believed should have alerted them to the fact that the plane was a civilian transport. He also stated that he knew it was a civilian Boeing from the double rows of windows:[30] "I saw two rows of windows and knew that this was a Boeing. I knew this was a civilian plane. But for me this meant nothing. It is easy to turn a civilian type of plane into one for military use..." Osipovich also stated that, in the pressure of the moment, he did not provide a full description of the intruder to Soviet ground controllers: "I did not tell the ground that it was a Boeing-type plane," he recalled, "They did not ask me."[28][31]

This omission of the identity of KAL 007 as a Boeing by Osipovich is evident in the communications subsequently released by the Russian Federation with the combat controller, Lt. Col. Titovnin (see Flight timeline and transcripts).

Commenting on the moment that KAL 007 slowed as it ascended from flight level 330 to flight level 350, and then on his maneuvering for missile launch, Osipovich said:

"They [KAL 007] quickly lowered their speed. They were flying at 400 kilometers per hour. My speed was more than 400. I was simply unable to fly slower. In my opinion, the intruder's intentions were plain. If I did not want to go into a stall, I would be forced to overshoot them. That's exactly what happened. We had already flown over the island [Sakhalin]. It is narrow at that point, the target was about to get away...Then the ground [controller] gave the command: 'Destroy the target...!' That was easy to say. But how? With shells?! I had already expended 243 rounds. Ram it? I had always thought of that as poor taste. Ramming is the last resort. Just in case, I had already completed my turn and was coming down on top of him. Then, I had an idea. I dropped below him about 2,000 meters... afterburners. Switched on the missiles and brought the nose up sharply. Success! I have a lock on."[32]

Post-attack flight

At the time of the attack, the plane had been cruising at an altitude of about 35,000 feet (11,000 m). Tapes recovered from the airliner's cockpit voice recorder indicate that the crew were unaware that they were off course and violating Soviet airspace. Immediately after missile detonation, the airliner began a 113-second arc upward, due to a damaged cross over cable between the left inboard and right outboard elevators.[33] At the apex of the arc, at altitude 38,250 feet (11,660 m),[33] either the pilot was able to turn off the autopilot or the autopilot tripped, at 18:26:46 GMT,[34] and the plane began to descend to 35,000 feet (11,000 m). At this point forward acceleration, velocity and altitude had all returned to their pre-attack states. The Boeing did not break up, explode or plummet immediately after the attack; it continued its gradual descent for four minutes, then leveled off at 16,424 feet (18:30–31 GMT), continuing at this altitude for almost five more minutes (18:35 GMT). The last cockpit voice recorder entry occurred at 18:27:46 while in this phase of the descent. At 18:28 GMT, the aircraft was reported turning to the north.[35] ICAO analysis concluded that the flight crew "retained limited control" of the aircraft.[36] Finally, the aircraft began to descend in spirals 2.6 miles (4.2 km) from Moneron Island before crashing, killing all 269 on board.[Notes 5] The aircraft was last seen visually by Osipovich, "somehow descending slowly" over Moneron Island.

According to an independent air accident investigator, "Emergency procedures call for saying 'Mayday' three times, followed by other information about the nature of the emergency, Brenner noted. The cockpit crew should have continued broadcasting until the last possible moment to help lead rescuers to the plane's location. But they did not."[37] The aircraft disappeared off long range military radar at Wakkanai, Japan at a height of 1,000 feet (300 m).[38]

KAL 007 was probably attacked in international airspace, with a 1993 Russian report listing the location of the missile firing outside its territory at 46°46′27″N 141°32′48″E / 46.77417°N 141.54667°E,[24][39] although the intercepting pilot stated otherwise in a subsequent interview. Initial reports that the airliner had been forced to land on Sakhalin were soon proved false. A Japanese fisherman later reported seeing two flashes of light and hearing an explosion, as well as smelling aviation fuel.[40]

Missile damage to plane

The following damage to the aircraft was determined by the ICAO from its analysis of the flight data recorder and cockpit voice recorder:

- The Hydraulics: KAL 007 had four redundant hydraulic systems of which systems one, two, and three were damaged or destroyed. There was no evidence of damage to system four.[34] The hydraulics provided actuation for all the primary flight controls; all secondary flight controls (except leading edge Krueger flaps); and landing gear retraction, extension, gear steering, and wheel braking. System four also had a third electrical power source. Each primary flight control axis received power from all four hydraulic systems.[41] Upon missile detonation, the jumbo jet began to experience oscillations (yawing) as the dual channel yaw damper was damaged. Yawing would not have occurred if hydraulic systems one or two were fully operational. The result is that the control column does not thrust forward upon impact (it should have done so as the plane was on autopilot) to bring down the plane to its former altitude of 35,000 feet. This failure of the autopilot to correct the rise in altitude indicates that hydraulic system number three, which operates the autopilot actuator, a system controlling the plane's elevators, was damaged or out. KAL 007's airspeed and acceleration rate both began to decrease as the plane began to climb. At twenty seconds after missile detonation a click was heard in the cabin, which is identified as the "automatic pilot disconnect warning" sound. Either the pilot or co-pilot had disconnected the autopilot and was manually thrusting the control column forward in order to bring the plane lower. Though the autopilot had been turned off, manual mode did not begin functioning for another twenty seconds. This failure of the manual system to engage upon command indicates failure in hydraulic systems one and two. With wing flaps up, "control was reduced to the right inboard aileron and the innermost of spoiler section of each side."[34]

- Left Wing: Contrary to Major Osipovich's statement in 1991 that he had taken off half of KAL 007's left wing,[28] ICAO analysis found that the wing was intact: "The interceptor pilot stated that the first missile hit near the tail, while the second missile took off half the left wing of the aircraft... The interceptor's pilot's statement that the second missile took off half of the left wing was probably incorrect. The missiles were fired with a two-second interval and would have detonated at an equal interval. The first detonated at 18:26:02 hours. The last radio transmissions from KE007 to Tokyo Radio were between 18:26:57 and 18:27:15 hours using HF [high frequency]. The HF 1 radio aerial of the aircraft was positioned in the left wing tip suggesting that the left wing tip was intact at this time. Also, the aircraft's maneuvers after the attack did not indicate extensive damage to the left wing."[42]

- Engines: The co-pilot reported to Captain Chun twice during the flight after the missile's detonation, "Engines normal, sir."[43]

- Tail Section: The first missile was radar-controlled and proximity-fused, and detonated 50 metres (160 ft) behind the aircraft. Sending fragments forward, it either severed or unraveled the crossover cable from the left inboard elevator to the right elevator.[33] This, with damage to one of the four hydraulic systems, caused KAL 007 to ascend from 35,000 feet (11,000 m) to 38,250 feet (11,660 m), at which point the autopilot was disengaged.

- Fuselage: Tiny shrapnel from the proximity-fused air-to-air missile that detonated 50 metres (160 ft) behind the aircraft, punctured the fuselage and caused rapid decompression of the pressurised cabin. The interval of 11 seconds between the sound of missile detonation picked up by the cockpit voice recorder and the sound of the alarm sounding in the cockpit enabled ICAO analysts to determine that the total size of the tiny ruptures to the pressurized fuselage was 1.75 square feet (0.163 m2). (The ICAO determined this from the 11 seconds that it took for the air to rush out of the cabin before the alarm was set off.[44])

Search and rescue

As a result of Cold War tensions, the search and rescue operations of the Soviet Union were not co-ordinated with those of the United States, South Korea and Japan. Consequently no information was shared, and each side endeavoured to harass or obtain evidence to implicate the other.[45] The flight data recorders were the key pieces of evidence sought by both factions, with the United States insisting that an independent observer from the ICAO be present on one of its search vessels in the event that they were found.[46] International boundaries are not well defined on the open sea, leading to numerous confrontations between the large number of opposing naval ships that were assembled in the area.[47]

Soviet search and rescue mission

The Soviets did not acknowlege shooting down the aircraft until 6 September.[48] Marshal of the Soviet Union and Chief of General Staff, Nikolai Ogarkov, 9 days after the shootdown, denied knowledge of where KAL 007 had gone down, "We could not give the precise answer about the spot where it [KAL 007] fell because we ourselves did not know the spot in the first place."[49] But nine years after, the Russian Federation handed over transcripts of Soviet military communications that showed that at least two documented search and rescue (SAR) missions were ordered to the last Soviet verified location of the descending jumbo jet, over Moneron Island: The first search was ordered from Smirnykh Air Base in central Sakhalin at 18:47 GMT, 9 minutes after KAL 007 had disappeared from Sovet radar screens, and brought rescue helicopters and KGB boats to the area.[50] The second search was ordered 8 minutes later by the Deputy Commander of the Far Eastern Military District, Gen. Strogov, and involved civilian trawlers that were in the area around Moneron. "The border guards. What ships do we now have near Moneron Island, if they are civilians, send [them] there immediately."[51] Moneron is just 4.5 miles (7.2 km) long and 3.5 miles (5.6 km) wide, located 24 miles (39 km) due west of Sakhalin Island at 46°15′N 141°14′E / 46.250°N 141.233°E; it is the only land mass in the whole Tatar Straits.

Human remains

Surface finds

No body parts were recovered by the Russians from the surface of the sea in their own territorial waters, though they would later turn over clothes and shoes to a joint US-Japanese delegation to Nevelsk on Sakhalin. Nothing was found by the joint US-Japanese-South Korean search and rescue/salvage operations in international waters at the designated crash site or within the 225 square nautical miles (770 km2) search area.[52]

Hokkaido finds

Eight days after the shootdown, human remains appeared on the north shore of Hokkaido, Japan. Hokkaido is located about 30 miles (48 km) below the southern tip of Sakhalin across the Soya Strait (the southern tip of Sakhalin is 35 miles (56 km) from Moneron Island which lies to the west of Sakhalin). The ICAO concluded that these objects were carried from Russian waters to the Japanese shores of Hokkaido by the southerly current west of Sakhalin Island. All currents of the Tsushima Strait relevant to Moneron Island flow to the north, except this southerly current between Moneron Island and Sakhalin Island.[53] These human remains, including body parts, tissues, and two partial torsos, totaled 13 in number. All were unidentifiable, but one partial torso was that of a Caucasian woman as indicated by auburn hair on a partial skull, and one partial body was of an Asian child (with glass imbedded). There was no luggage recovered. Of the non human remains that the Japanese recovered were various items including dentures, newspapers, seats, books, 8 "KAL" paper cups, shoes, sandals, and sneakers, a camera case, a "please fasten seat belt" sign, an oxygen mask, a handbag, a bottle of dish washing fluid, several blouses, an identity card belonging to 25 year old passenger Mary Jane Hendrie[54] of Sault Ste. Marie, Canada, and the business card of passenger Kathy Brown-Spier.[55] All of these items generally come from the passenger cabin of an aircraft. There were none of the items found that generally come from the cargo hold of a plane, such as suitcases, packing boxes, industrial machinery, instruments and sports equipment.

Soviet diver reports

In 1991, Izvestia published a series of interviews with Soviet military personnel who had been involved in salvage operations to find and recover parts of the aircraft.[28] After three days of searching using trawlers, side-scan sonar and diving bells, the aircraft wreckage was located by Russian searchers at a depth of 174 metres (571 ft) near Moneron Island.[28][56] Since no human remains or luggage were found on the surface in the impact area, the divers expected to find passengers incarcerated in the submerged wreckage of the aircraft on the seabed. However when they visited the site two weeks after the shootdown, they found that the wreckage was in small pieces:

"I had the idea that it would be intact. Well, perhaps a little banged up... The divers would go inside the aircraft and see everything there was to see. In fact it was completely demolished, scattered about like kindling. The largest things we saw were the braces which are especially strong—they were about one and a half or two meters long and 50-60 centimeters wide. As for the rest—broken into tiny pieces..."[28]

According to Izvestia, the divers had only 10 encounters with passenger remains (tissues and body parts) in the debris area, including one partial torso.[57]

Tinro ll submersible Captain Mikhail Igorevich Girs' diary: Submergence 10 October. Aircraft pieces, wing spars, pieces of aircraft skin, wiring, and clothing. But—no people. The impression is that all of this has been dragged here by a trawl rather than falling down from the sky…’[58]

ICAO also interviewed a number of these divers for its 1993 report: "In addition to the scraps of metal, they observed personal effects, such as clothing, documents and wallets. Although some evidence of human remains was noticed by the divers, they found no bodies."[59]

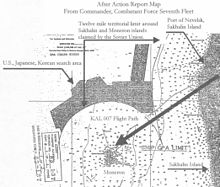

Search for KAL 007 in international waters

From early in September until the beginning of November, the U.S. with the Japanese and South Koreans carried out joint search and rescue and then salvage operations. These missions met with interference by the Soviets,[60] in violation of the 1972 Incident at Sea agreement, and included false flag and fake light signals, sending an armed boarding party to threaten to board a U.S.-chartered Japanese auxiliary vessel (blocked by U.S. warship interposition), interfering with a helicopter coming off the USS Elliot, attempted ramming of rigs used by the South Koreans in their "quadrant" search, hazardous maneuvering of the Gavril Sarychev and near collision with the USS Callaghan, removing U.S. sonars, setting false "pingers" in deep international waters, sending Backfire bombers armed with air-to-surface nuclear-armed missiles to threaten U.S. naval units, "criss-crossing" in front of U.S. combatant vessels, cutting and attempted cuttings of moorings of the Japanese auxiliary vessels, particularly the Kaiko Maru III, and radar lock-ons by a Soviet Kara-class cruiser, the Petropavlosk, and a Kashin-class destroyer, the Odarennyy, targeting U.S. naval vessels.[61][62]

According to the ICAO: "The location of the main wreckage was not determined...the approximate position was 46°34′N 141°17′E / 46.567°N 141.283°E, which was in international waters." This point is about 41 miles (66 km) from Moneron Island, about 45 miles (72 km) from the shore of Sakhalin and 33 miles (53 km) from the point of attack.[63]

Rear Admiral Walter T. Piotti Jr, commander of Task Force 71 of 7th Fleet, believed the search for KAL 007 in international waters to have been a search in the wrong place and assessed:[64]

"Had TF [task force] 71 been permitted to search without restriction imposed by claimed territorial waters, the aircraft stood a good chance of having been found. No wreckage of KAL 007 was found. However, the operation established, with a 95% or above confidence level, that the wreckage, or any significant portion of the aircraft, does not lie within the probability area outside the 12 nautical miles (22 km) area claimed by the Soviets as their territorial limit."

At a hearing of the ICAO on Sept.15, 1983, J. Lynn Helms, the head of the Federal Aviation Administration, stated:[65] "The U.S.S.R. has refused to permit search and rescue units from other countries to enter Soviet territorial waters to search for the remains of KAL 007. Moreover, the Soviet Union has blocked access to the likely crash site and has refused to cooperate with other interested parties, to ensure prompt recovery of all technical equipment, wreckage and other material."

Political events

The shootdown happened at a very tense time in U.S.-Soviet relations during the Cold War. The U.S. adopted a strategy of releasing a substantial amount of hitherto highly classified intelligence information in order to exploit a major propaganda advantage over the U.S.S.R.[66] George Schultz held a press conference about the incident at 10:45 on September 1, during which he divulged some details of intercepted Soviet communications and denounced the actions of the Soviet Union.[67]

General Secretary Yuri Andropov, on the advice of Defense Minister Dmitriy Ustinov, but against advice of the Foreign Ministry, initially decided not to make any admission of downing the airline, on the premise that no-one would find out or be able to prove otherwise.[48] Consequently the TASS news agency reported twelve hours after the shootdown only that an unidentified aircraft, flying without lights, had been intercepted by Soviet fighters after it violated Soviet airspace over Sakhalin. The aircraft had allegedly failed to respond to warnings and "continued its flight toward the Sea of Japan".[48][67] Some commentators believe that the manner in which the political events were handled by the Soviet government was affected by the failing health of Andropov, who was permanently hospitalised in late September or early October 1983.[68]

On September 5, 1983, U.S. President Ronald Reagan condemned the shooting down of the airplane as the "Korean airline massacre", a "crime against humanity [that] must never be forgotten" and an "act of barbarism ... [and] inhuman brutality".[69] The following day, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, Jeane Kirkpatrick, commissioned an audio-visual presentation in the United Nations Security Council, using audio tapes of the Soviet pilots' radio conversations and a map of Flight 007's path in depicting its shooting down. Following this presentation, TASS acknowledged for the first time that the aircraft had indeed been shot down after warnings were ignored. The Soviets challenged many of the facts presented by the U.S., and for the first time, mentioned the presence of a USAF RC-135 surveillance aircraft whose path had crossed that of KAL 007.

On 7 September, Japan and the United States jointly released a transcript of Soviet communications, intercepted by the listening post at Wakkanai, to an emergency session of the United Nations Security Council.[70] US president Reagan issued a National Security Directive stating that the Soviets were not to be let off the hook, and initiating "a major diplomatic effort to keep international and domestic attention focused on the Soviet action."[23] The move was seen by the Soviet leadership of confirmation of the West's bad intentions.

A high level U.S.-Soviet summit, the first for nearly a year, was scheduled for 8 September 1983 in Madrid.[48] The Schultz-Gromyko meeting went ahead, but was overshadowed by the KAL 007 event.[48] It ended acrimoniously, with Schultz stating: "Foreign Minister Gromyko's response to me today was even more unsatisfactory than the response he gave in public yesterday. I find it totally unacceptable."[48] President Reagan ordered the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) on September 15, 1983 to revoke the licence of Aeroflot Soviet Airlines to operate flights to and from the U.S. Aeroflot flights to North America were consequently available only through Canadian and Mexican cities, forcing the Soviet foreign minister to cancel his scheduled trip to the United Nations. Aeroflot service to the U.S. was not restored until April 29, 1986.[71]

An emergency session of the ICAO was held in Montreal.[72] On September 12, 1983, the Soviet Union was forced to use its veto to block a United Nations resolution condemning it for shooting down the aircraft.[47]

Shortly after the Soviet Union shot down KAL 007, legislatures in New York and New Jersey denied Soviet aircraft landing rights, in violation of the United Nations Charter that required the host nation to allow all member countries access to the UN. In reaction, TASS and some at the UN raised the question of whether the U.N. should move its headquarters from the United States. Charles Lichenstein, acting US permanent representative to the U.N. under Ambassador Kirkpatrick, responded, "We will put no impediment in your way. The members of the US mission to the United Nations will be down at the dockside waving you a fond farewell as you sail off into the sunset." Administration officials were quick to announce that Lichenstein was speaking only for himself.[73]

In the Cold War context of Operation RYAN, the Strategic Defence Initiative, Pershing II missile deployment in Europe and the upcoming Exercise Able Archer, the Soviet Government perceived the incident with the Korean airliner to be part of a US war drive.[68] The Soviet hierarchy took the official line that KAL Flight 007 was on a spy mission, as it "flew deep into Soviet territory for several hundred kilometres, without responding to signals and disobeying the orders of interceptor fighter planes"."[3] They claimed its purpose was to probe the air defences of highly sensitive Soviet military sites in the Kamchatka Peninsula and Sakhalin Island".[3] The Soviet government expressed regret over the loss of life, but offered no apology and did not respond to demands for compensation.[74] Instead, the U.S.S.R. blamed the CIA for this "criminal, provocative act",[3] and argued that the U.S. case was incredible:[3]

"Today, when all versions have been viewed from all possible angles, when leading specialists, including pilots who have flown Boeings for thousands of hours, have declared that three computers could not break down all at once, and neither could five radio transmitters, there can be no doubt as to the intentions of the intruder plane. The Soviet pilots who intercepted the aircraft could not have known that it was a civilian plane. It was flying without the navigation lights,[Notes 6] in conditions of poor visibility and did not respond to radio signals."

Investigations

NTSB

Since the aircraft had departed from US soil and US nationals had died in the incident, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) was legally required to investigate. On the morning of September 1, the NTSB chief in Alaska, James Michelangelo, received an order from the NTSB in Washington at the behest of the State Department requiring all documents relating to the NTSB investigation to be sent to Washington, and notifying him that the State Department would now conduct the investigation.[75] The US State Department, after closing the NTSB investigation on the grounds that it was not an accident, pursued an ICAO investigation instead. Commentators such as Johnson point out that this action was illegal, and that in deferring the investigation to the ICAO, the Reagan administration effectively precluded any politically or militarily sensitive information from being subpoenaed that might have embaressed the administration or contradicted its version of events.[76] Unlike the NTSB, ICAO can neither subpoenae persons or documents and is dependent on the governments involved, particularly in this incident, the U.S., the Soviet Union, Japan, and South Korea, to supply evidence voluntarily.

Initial ICAO investigation (1983)

ICAO had only one experience of investigation of an air disaster prior to the KAL 007 shootdown. This was the incident of February 21, 1973, when Libyan Arab Airlines Flight 114 was shot down by Israeli F-4 jets over the Sinai Peninsula. ICAO convention required the state in whose territory the accident had taken place (the U.S.S.R.) to conduct an investigation together with the country of registration (South Korea), the country whose air traffic control the aircraft was flying under (Japan), as well as the aircraft's manufacturer (Boeing).

The ICAO investigation did not have the authority to compel the states involved to hand over evidence, instead having to rely on what they voluntarily submitted.[77] Consequently, the investigation did not have access to sensitive evidence such as radar data, intercepts, ATC tapes, or the Flight Data Recorder (FDR) and Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) (whose discovery the U.S.S.R. had kept secret). A number of simulations were conducted with the assistance of Boeing and Litton (the manufacturer of the navigation system).[78]

The ICAO released their report December 2, 1983, which concluded that the violation of Soviet airspace was accidental: One of two explanations for the aircraft's deviation was that the autopilot had remained in HEADING hold instead of INS mode after departing Anchorage. They postulated that this inflight navigational error was caused either by the crew not selecting INS mode, or inertial navigation not activating when selected, due to the aircraft already being too far off track).[8] It was determined that the crew did not notice this error or subsequently perform navigational checks, for example using OMEGA,[79] that would have revealed that the aircraft was diverging further and further from its assigned route. This was later deemed to be caused by a "lack of situational awareness and flight deck coordination".[80]

The report included a statement by the Soviet Government claiming "no remains of the victims, the instruments or their components or the flight recorders have so far been discovered".[81] However, this statement was subsequently shown to be untrue by Boris Yeltsin's release in 1993 of a November 1983 memo from KGB head Viktor Chebrikov and Defence Minister Dmitry Ustinov to Yuri Andropov. This memo stated "In the third decade of October this year the equipment in question (the recorder of in-flight parameters and the recorder of voice communications by the flight crew with ground air traffic surveillance stations and between themselves) was brought aboard a search vessel and forwarded to Moscow by air for decoding and translation at the Air Force Scientific Research Institute."[82] The Soviet Government statement would further be contradicted Soviet civilian divers who later recalled that they viewed wreckage of the aircraft on the bottom of sea for the first time on September 15, two weeks after the plane had been shot down.[83]

Following publication of the report, the ICAO adopted a resolution condeming the Soviet Union for the attack.[84] Furthermore, the report led to an unanimous amendment in May 1994 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation that defined the use of force against civilian airliners in more detail.[85] The amendment to section 3(d) reads in part: "The contracting States recognize that every State must refrain from resorting to the use of weapons against civil aircraft in flight and that, in case of interception, the lives of persons on board and the safety of aircraft must not be endangered."[86]

U.S. Air Force radar data

It is customary for the Air Force to impound radar trackings involving possible litigation in cases of aviation accidents.[87] In the civil litigation for damages, the United States Department of Justice explained that the tapes from the Air Force radar installation at King Salmon, Alaska pertinent to KAL 007's flight in the Bethel area had been destroyed and could therefore not be supplied to the plaintiffs. At first Justice Department lawyer Jan Van Flatern stated that they were destroyed 15 days after the shootdown. Later, he said he had "mispoken" and changed the time of destruction to 30 hours after the event. A Pentagon spokesman concurred, saying that the tapes are re-cycled for reuse from 24–30 hours afterwards,[88] however the fate of KAL 007 was known inside this timeframe.[89]

Interim developments

Hans Ephraimson-Abt, whose daughter Alice Ephraimson-Abt had died on the flight, chaired the American Association for Families of KAL 007 Victims. He single-handedly pursued three US administrations for answers about the flight, flying to Washington 250 times and meeting with 149 State Department officials. Following following the dissolution of the USSR, Ephraimson-Abt persuaded US Senators Ted Kennedy, Sam Nunn, Carl Levin, and Bill Bradley to write to the Soviet President, Mikhail Gorbachev requesting information about the flight.[90] Glasnost reforms in the same year brought about a relaxation of press censorship; consequently reports started to appear in the Soviet press suggesting that the Soviet military knew the location of the wreckage and had possession of the flight data recorders.[28][91] In December 1991, Senator Jesse Helms of the Committee on Foreign Relations, wrote to Boris Yeltsin requesting information concerning the survival of passengers and crew of KAL 007 including the fate of Congressman Larry McDonald.

On June, 17, 1992, President Yeltsin revealed that after the 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt, concerted attempts were made to locate Soviet-era documents relating to KAL 007. He mentioned the discovery of "a memorandum from K.G.B. to the Central Committee of the Communist Party", stating that a tragedy had taken place and adding that there are documents "which would clarify the entire picture". Yeltsin said the memo continued to say that "these documents are so well concealed that it is doubtful that our children will be able to find them."[92] On September 11, 1992 Yeltsin officially acknowledged the existence of the black boxes, and promised to give South Korean Government a transcript of the flight recorder contents as found in KGB files.

In October 1992, Hans Ephraimson-Abt led a delegation of families and US State Department officials to Moscow at the invitation of President Yeltsin.[93] During a state ceremony at St. Catherine's Hall in the Kremlin, the KAL family delegation was handed a portfolio containing partial transcripts of the KAL 007 cockpit voice recorder, translated into Russian, and documents of the Politburo pertaining the tragedy.

In November 1992, President Yeltsin handed the two black box containers to Korean President Roh Tae-Woo, but not the tapes themselves; The following month, the ICAO voted to reopen KAL 007 investigation in order to take the newly released information in account. The tapes were handed to ICAO in Paris on 8 January 1993.[7] Also handed over at the same time were tapes of the ground to air communications of the Soviet military.[94] The tapes were transcribed by the Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la sécurité de l'Aviation Civile (BEA) in Paris in the presence of representatives from Japan, The Russian Federation, South Korea, and the United States.[94]

A 1993 official enquiry by the Russian Federation absolved the Soviet hierarchy of blame, determining that the incident was a case of mistaken identity.[68] On May 28, 1993, the ICAO presented its second report to the Secretary-General of the United Nations.

Soviet memoranda

In 1992, Russian president Boris Yeltsin disclosed five top-secret memos dating from a few weeks after of the downing of KAL 007 in 1983.[Notes 7] The memos contained Soviet communications (from KGB Chief Viktor Chebrikov and Defence Minister Dmitry Ustinov to Premier Yury Andropov) that indicated that they knew the location of KAL 007's wreckage while they were simulating a search and harassing the American Navy; they had found the sought-after flight data recorder on October 20, 1983 (50 days after the incident),[95] and had decided to keep this knowledge secret, the reason being that the tapes could not unequivocally support their firmly-held view that KAL 007's flight to Soviet territory was a deliberately planned intelligence mission.[96][97]

Simulated search efforts in the Sea of Japan are being performed by our vessels at present in order to dis-inform the U.S. and Japan. These activities will be discontinued in accordance with a specific plan...

Therefore, if the flight recorders shall be transferred to the western countries their objective data can equally be used by the U.S.S.R. and the western countries in proving the opposite view points on the nature of the flight of the South Korean airplane. In such circumstances a new phase in anti-Soviet hysteria cannot be excluded.

In connection with all mentioned above it seems highly preferable not to transfer the flight recorders to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) or any third party willing to decipher their contents. The fact that the recorders are in possession of the U.S.S.R. shall be kept secret...

As far as we are aware neither the U.S. nor Japan has any information on the flight recorders. We have made necessary efforts in order to prevent any disclosure of the information in future.

Looking to your approval. D.Ustinov, V. Chebrikov (photo[Notes 8]) ____ December 1983"

The third memo acknowledges that analysis of the black box tapes showed no evidence of the Soviet interceptor attempting to contact KAL 007 via radio nor any indication that the KAL 007 crew was aware of warning shots being fired.

"However in case the flight recorders shall become available to the western countries their data may be used for: Confirmation of no attempt by the intercepting aircraft to establish a radio contact with the intruder plane on 121.5 MHz and no tracers warning shots in the last section of the flight"[98]

That the Soviet search was simulated (while knowing the wreckage lay elsewhere) also is suggested by the article of Mikhail Prozumentshchikov, Deputy Director of the Russian State Archives of Recent History, commemorating the twentieth anniversary of the airplane's shooting down. Commenting on the Soviet and American searches: "Since the U.S.S.R., for natural reasons, knew better where the Boeing had been downed...it was very problematical to retrieve anything, especially as the U.S.S.R. was not particularly interested".[99]

Revised ICAO report (1993)

On November 18, 1992 Russian President Boris Yeltsin, in a goodwill gesture to South Korea during a visit to Seoul to ratify a new treaty, released both the flight data recorder (FDR) and cockpit voice recorder (CVR) of KAL 007.[100] Initial South Korean research showed the FDR to be empty and the CVR to have an unintelligible copy. The Russians then released the recordings to the ICAO Secretary General.[101] The ICAO report continued to support the initial assertion that KAL 007 accidentally flew in Soviet airspace,[80] after listening to the flight crew's conversations recorded by the CVR.

In addition, the Russian Federation released "Transcript of Communications. U.S.S.R. Air Defence Command Centres on Sakhalin Island" transcripts to ICAO—this new evidence triggered the revised ICAO report in 1993[102] and is appended to it. These transcripts (of a number of tracks recordings on two reels) are time specified, some to the second, of the communications between the various command posts and other military facilities on Sakhalin from the time of the initial orders for the shootdown and then through the stalking of KAL 007 by Maj. Osipovoich in his Sukhoi 15 interceptor, the attack as seen and commented on by General Kornukov, Commander of Sokol Air Base, down the ranks to the Combat Controller Lt. Col. Titovnin, the post-attack flight of KAL 007 until it had reached Moneron Island, the descent of KAL 007 over Moneron, the initial Soviet SAR missions to Moneron, the futile search of the support interceptors for KAL 007 on the water, and ending with the debriefing of Osipovich on return to base. Some of the communications are the telephone conversations between superior officers and subordinates and involve commands to them, while other communications involve the recorded responses to what was then being viewed on radar tracking KAL 007. These multi-track communications from various command posts telecommunicating at the same minute and seconds as other command posts were communicating provide a "composite" picture of what was taking place.[103]

The data from the CVR and the FDR revealed that the recordings broke off after the first minute and 44 seconds of KAL 007's post missile detonation 12 minute flight. ICAO notes that break off of tape is consonant with a high speed crash but indicates that there was no high speed crash at that time. "Spliced joints were found at approximately 108, 440, 442, and 463 ft (141 m) from the beginning of the tape. The middle two were spaced at a distance corresponding to the length of the tape between the two reels and the last data was recorded between these two joints. It was not unusual for the tape to break as a result of high speed impacts, near where it left the reels.".[104] The remaining minutes of flight would be supplied by the Russia 1992 submission to ICAO of the real-time Soviet military communication of the shootdown and aftermath.

The fact that both recorder tapes stopped exactly at the same time 1 minute and 44 seconds after missile detonation (18:38:02 GMT) without the tape portions for the more than 10 minutes of KAL 007's post detonation flight before it descended below radar tracking (18:38 GMT) finds no explanation in the ICAO analysis, "It could not be established why both flight recorders simultaneously ceased to operate 104 seconds after the attack. The power supply cables were fed to the rear of the aircraft in raceways on opposite sides of the fuselage until they came together behind the two recorders."[33]

Passenger pain and suffering

Passenger pain and suffering was an important factor in determining the level of compensation that was paid by Korean Air Lines.

Fragments from the proximity fused R-98 medium range air-to-air missile exploding 50 metres (160 ft) behind the tail caused punctures to the pressurized passenger cabin.[44] When one of the flight crew radioed Tokyo Airport one minute and two seconds after missile detonation his breathing was already "accentuated", indicating to ICAO analysts that he was speaking through the microphone located in his oxygen mask, "Korean Air 007 ah... We are... Rapid compressions. Descend to 10,000."[105]

Two expert witnesses testified at a Court of Appeals trial on the issue of pre-death pain and suffering. Captain James McIntyre, an experienced Boeing 747 pilot and aircraft accident investigator, testified that shrapnel from the missile caused rapid decompression of the cabin, but left the passengers sufficient time to don oxygen masks: "McIntyre testified that, based upon his estimate of the extent of damage the aircraft sustained, all passengers survived the initial impact of the shrapnel from the missile explosion. In McIntyre's expert opinion, at least 12 minutes elapsed between the impact of the shrapnel and the crash of the plane, and the passengers remained conscious throughout."[106]

Alternative theories

Flight 007 has been the subject of ongoing controversy and has spawned a number of conspiracy theories,[107] primarily as a result of Cold War disinformation campaigns conducted at the time, as well as the suppression of evidence such as the flight data recorders and the role of USAF surveillance aircraft. Furthermore, some commentators felt that the ICAO report failed to address key points adequately in its investigation, such as the reason for the aircraft's deviation.[108][109] Some of the conspiracy theories were subsequently proved to be groundless when the flight data recorder evidence became available in 1993, however others remain unrefuted.

One of the first theories was that Space Shuttle Challenger and a satellite were monitoring the airliner's progress over Soviet territory. Defence Attaché, which printed this claim, was sued by Korean Air Lines and forced to pay damages as well as print an apology.[110]

In 1994, Robert W Allardyce and James Gollin wrote Desired Track: The Tragic Flight of KAL Flight 007, supporting the spy mission theory.[111] In 2007, they reiterated their position in a series of articles in Airways Magazine, arguing that the investigation by the International Civil Aviation Organization was a cover-up.[112]

Around the time that KAL 007 was entering into Soviet airspace, a U.S. RC-135 reconnaisance plane was in the area to capture the telemetry of an intercontinental ballistic missile that was to hit the Klyuchi target range on Kamchatka.[113] The capabilities and role of a United States Air Force RC-135, that was in the vicinity at the time of the incident, have not been disclosed by the United States military. During the civil litigation for damages to the families of the victims of the shoot-down, Chief Justice of the District Court of Washington, D.C., Aubrey Robinson, ruled out legal recourse to finding out on grounds that it would endanger U.S. national security. On April 18, 1984, he allowed questions to the military, "but only in respect to uncovering the legal duty of the military to warn or advise civilian aircraft."[114]

In January 1996, Hans Ephraimson, chairman of the "American Association for Families of KAL 007 Victims", claimed that South Korean President Chun Doo-hwan accepted $4 million from Korean Air in order to gain "government protection" during the investigation of the shootdown.[115]

More recently in 2000, Rescue 007: Untold Story of KAL 007 and its Survivors,[116] which is promoted by the "International Committee for the Rescue of KAL 007 Survivors"[117] advanced a theory that KAL 007, though crippled, was able to land on water safely enough for at least some of its occupants to have been rescued by the Soviets in Soviet territorial waters, then retained, finally to be incarcerated in various locations in the Soviet Union. This best explains, according to the organization, the Soviet 9 year concealment of the black box tapes, the lack of bodies, body parts, and luggage, reports of survivor sightings,[118] and the reported Soviet harassment of U.S. search efforts and preventing conducting of the search in Soviet waters. The organization believes that there is credible evidence concerning the subsequent whereabouts of passengers Congressman Larry McDonald and 5 year old Noelle Anne Grenfell[119] to reopen the investigation into the shootdown and aftermath.

Though independent of the initiative by Senator Jesse Helms to launch a CIA investigation of the shootdown while he was ranking member of the Minority Staff (Republican) of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, the International Committee for the Rescue of KAL 007 Survivors is undertaking a dissemination to the media of the 1991 Republican staff study[120] on the shootdown. The organization fully supports both the Helms letter to Yeltsin[121] requesting information about survivors, including Larry McDonald, and supports the conclusion of the study, “KAL 007 probably ditched successfuly, there may have been survivors, the Soviets have been lying massively, and diplomatic efforts need to be made to return the possible survivors.”

Another theory was suggested by Michael Brun in his book Incident at Sakhalin: The True mission of KAL Flight 007.[122] According to this book, KAL007 was involved in a spy mission to trigger U.S.S.R. air defences and to cover the missions of several USAF spy airplanes. The Korean aircraft was communicating with Tokyo-Narita controllers around half an hour after the official shootdown moment. A large air battle occurred between Soviet Air Force and USAF, during which the Soviets shot down several American aircraft, including a RC-135, an EF-111 and probably even an SR-71. The SU-15 pilot, Major Osipovich, flew 2 sorties and shot down 2 targets (contradicted by the 1991 interview with Osipovich in 1991[28]). The whereabouts of the KAL-007 wreckage is not known to anyone, but is probably 500 kilometres (310 mi) away from the Moneron island. The theory postulates further that the real cause of the destruction is not known, but could be a surface-to-air missile from USS Badger (similar case with USS Vincennes shooting down of Iran Air Flight 655) or from Japanese forces, who could not identify the airliner which was keeping radio silence.

Aftermath

The FAA temporarily closed Airway R-20 ("Romeo 20"), the air corridor that Korean Air Flight 007 was meant to follow, on September 2. However airlines fiercely resisted the closure of this popular route, the shortest of five corridors spanning Alaska and the Far East. It was therefore reopened on October 2 after safety and navigational aids were checked.[123][124]

NATO had decided, under the impetus of the Reagan administration, to deploy Pershing II and cruise missiles in West Germany.[125] This deployment would have placed missiles just 6–10 minutes striking distance from Moscow. Support for the deployment was wavering and it looked doubful that it would be carried out. However when the Soviet Union shot down Flight 007, the U.S. was able to galvanize enough support at home and abroad to enable the deployment to go ahead.[126]

The unprecedented disclosure of the communications intercepted by the United States and Japan revealed a considerable amount of information about their intelligence systems and capabilities. National Security Agency director Lincoln D. Faurer commented: "...as a result of the Korean Air Lines affair, you have already heard more about my business in the past two weeks than I would desire...For the most part this has not been a matter of unwelcome leaks. It is the result of a conscious, responsible decision to address an otherwise unbelievable horror."[127] Changes that the Soviets subsequently made to their codes and frequencies reduced the effectiveness of this monitoring by 60%.[128]

The U.S. KAL 007 Victims' Association, under the leadership of Hans Ephraimson-Abt, successfully lobbied U.S. Congress and the airline industry to accept an agreement that would ensure that future victims of airline accidents would be compensated quickly and fairly by increasing compensation and lowering the burden of proof of airliner misconduct.[93] This legislation has had far-reaching effects for the victims of subsequent aircraft disasters.

The U.S. decided to utilize military radars to extend air traffic control radar coverage from 200 miles (320 km) to 1,200 miles (1,900 km) out from Anchorage.[Notes 9] In 1986, the United States, Japan and the Soviet Union set up a joint air traffic control system to monitor aircraft over the North Pacific, thereby giving the Soviet Union formal responsibility to monitor civilian air traffic, and setting up direct communication links between the controllers of the three countries.[129]

Ronald Reagan announced on September 16, 1983 that the Global Positioning System (GPS) would be made available for civilian use, free of charge, once completed in order to avert similar navigational errors in future.[130] Furthermore, the interface of the autopilot used on large airlines was modified to make it more obvious whether it is operating in HEADING mode or INS mode.[8]

Flight timeline and transcripts

The following transcript is compiled from Japanese electronic intercepts of Soviet Su-15 transmissions,[Notes 10] a transcript of communications of U.S.S.R. Air Defence Command Centres on Sakhalin Island (released in 1993), civil air traffic controller recordings from Tokyo and Anchorage, and the KAL 007 cockpit voice recorder (released in 1993). The ICAO co-ordinated the times of Soviet transmissions with partial, but time-stamped communications intercepted by Japan. Some Air Combat Controller fighter vectoring, fuel read-outs and inter-command post "chatter" is not included.

| Speaker | Source of transcript |

|---|---|

| Soviet ground controllers and command posts | 1993 Russian transcript[131] |

| Soviet fighter pilots | 1983 US-Japanese intercept of pilot transmissions[132]/1993 Russian transcript[131] |

| KAL 007 cockpit/cabin | 1993 CVR[131] |

| KAL 007 radio transmissions | ATC recording[133] |

| Tokyo/Anchorage ATC[133] | ATC recording[133]/CVR[131] |

| Other | Radar[133]/ATC[133]/FDR[131] |

| Time (GMT) | Comment |

|---|---|

| 12:50:12 | KAL is cleared for take-off in Anchorage[79]

KAL 007: "Uh clearance Korean 007, uh have information sierra Seoul at three one zero" |

| 12:50:18 | Anchorage ATC: "Korean Air 007 heavy is cleared to Seoul via the Anchorage eight departure then as filed climb and maintain flight level 310; departure frequency 118.6, squawk 6072" |

| 12:50:34 | KAL 007: "Korean 007 cleared to Seoul; Anchorage eight departure, climb and maintain 310; 1186 6072" |

| 12:50:43 | Anchorage ATC: "Korean 007 heavy read back was correct" |

| 12:58:33 | KAL 007: "Korean 007 ready for takeoff" |

| 12:58:36 | ATC "Korean 007 heavy roger; departure frequency will be 118.3, same as tower; cleared for takeoff, runway 32. |

| 13:01:12 | ATC "Korean 007 heavy, Anchorage departure. Radar contact - climb and maintain flight level 310. Turn left heading 220" |

| 13:01:22 | KAL 007: "Roger 220 climb and maintain 310 roger" |

| 13:03:07 | Pilot enaged autopilot on a heading of 220 degrees.[8] |

| 13:03:30 | Estimated point that the pilot selected INS mode.[8] |

| 13:27:50 | KAL flies beyond the range of Anchorage civilian radar coverage

"ATC: "Korean Air zero zero seven radar service is terminated. Contact Center 125.2 good morning" |

| 13:27:53 | KAL 007: "KE007 two five two good morning" |

| 13:28:01 | KAL 007 reports climbing to 31,000 feet (9,400 m): "Anchorage Center Korean Air 007, good morning. Now leaving 300 for 310" |

| 13:28:06 | ATC: "Korean Air 007 roger, report Bethel" |

| 13:28:11 | KAL 007: "Report Bethel roger" |

| 13:30 | KAL 007 5.6 miles (9.0 km) off course at Cairn Mountain.[134] |

| 13:50 | KAL 007 12.6 miles (20.3 km) off course at Bethel.[135] |

| 13:50:09 | KAL 007 reports reaching Bethel: "Anchorage, Korean Air 007" |

| 13:50:12 | ATC: "Korean Air 007, go ahead" |

| 13:50:14 | KAL 007: "007 Bethel at 49, flight level 310. Estimate NABIE at 1430 219.0 minus 49295 diagonal 25" (But according to King Salmon military radar, KAL 007 is actually 12.6 nm off course) |

| 13:50:28 | ATC: "Korean Air zero zero seven roger report NABIE to Anchorage on 1278" |

| 13:50:33 | KAL 007: "1278 roger" |

| 13:50:42 | ATC: "Go ahead" |

| 13:50:43 | KAL 015, that had taken off 15 minutes after KAL 007 and is also flying on route Romeo 20, reports over VHF for KAL 007, which is too far off course to itself report over VHF, that KAL 007 has reached waypoint NABIE: "Korean Air 007 says NABIE one four three zero TJ" |

| 15:51 | KAL 007 entered Soviet airspace over the Kamchatka Peninsula. |

| 17:45 | KAL 007 re-entered international airspace over the Sea of Okhotsk. |

| 17:49 | Capt. Solodkov: "Two pilots have just been sent up, command at the command post, we do not know what is happening just now, it's heading straight for our Island [Sakhalin], to Terpienie [Bay] somehow, this looks very suspicious to me, I don't think the enemy is stupid, can it be one of ours?" |

| 17:53 | First documented order for shootdown.

General Anatoli Kornukov (Photo[Notes 11]), commander of Sokol Air base on Sakhalin to the command post of General Valeri Kamenski, Commander of Air Defense Forces for the Far East Military District, "...simply destroy [it] even if it is over neutral waters? Are the orders to destroy it over neutral waters? Oh, well."[136] |

| 17:54:26 | The Cockpit Voice Recorder records about the last half hour of an aircraft's flight continually playing over itself as the flight progresses. KAL 007's CVR tape (as well as the tape of the Flight Data Recorder) was stopped one minute and 44 seconds after missile detonation at 18:26:02, though the flight would continue for over 10 minutes more. Here is the beginning of the half hour taping of KAL 007's Flight Deck conversation: |

| 17:54:26 | Flight Deck: "Have you had a long flight recently?" |

| 17:54:28 | Flight Deck: "From time to time" |

| 17:54:30 | Flight Deck: "Sounds good, as far as I know Chief Pilot Park has a long flight occasionally, but Chief Pilot Lee has..." |

| 18:00 | Ground controllers are given orders on how to direct the jets to intercept the Korean airliner

Kornukov: "Bring him up, bring Osipovich in to the prescribed distance. You do not engage him to the target from the aft hemisphere, you do not engage him right on the tail, keep the angle of approach." Kozlov [Fighter Control, Sokol airbase]: "Roger, executing. " Kornukov: "Don't forget, it [the target] has cannons in the rear there" Kozlov: "Roger, executing. But faster, for the fighter, rather, the target is entering the zone above the one-hundred-kilometers waters [identification zone]." Kozlov: "Wilco" |

| 18:04-05 | KAL 007, off course, and KAL 015, on course, compare wind velocity and direction. KAL 015 is enountering tailwinds while KAL 007 is encountering headwinds

KAL 015: "Um Um We are now having an unexpected strong tailwind How much do you get there? How much and which direction?" KAL 007: "206. Ask him how many knots?..." KAL 007: "Ah! You got so much! We still got headwind. Headwind 215 degrees, 15 knots." KAL 015: "Is it so? But according to flight plan wind direction 360, 15 knots approximately." KAL 007: "Well, it may be like this." |

| 18:05:53 | Maj. Osipovich, callsign "805", in his Su-15 intercepted KAL 007: "On heading 240" |

| 18:05:56 | Osipovich: "Am observing." |

| 18:08 | Kozlov (Combat Controller Sokol Airbase): "He has the target in sight"

Kornukov: "He can see it? How many jet trails are coming from it?" Kozlov: "Say again, Kornukov: How many jet trails are there, if there are four jet trails, then it's an RC-135" |

| 18:11:30-39 | KAL 007 Flight Crew: "I have heard that there is currency exchange at your airport." "In the airport currency exchange? What kind of money?" "Dollar to Korean money." "That's in the domestic building too, domestic building too." |

| 18:11 | Air Controller Titovnin: "Can you see the target, 805?" |

| 18:11 | Osipovich: "I see both visually and on the screen". |

| 18:11 | Lt. Col. Titovnin: "Roger, report lock-on".[137] |

| 18:12 | Kornukov: "Gerasimenko!"

Lt. Col. Gerasimenko (41st fighter Regiment Command Post): "Yes" Kornukov: "Well, what, don't you understand? I said bring [him] up to a range of 4 kilometers, 4-5 kilometers, identify the target. You understand that weapons are going to have to be used now and you are holding [him] at a range of 10. Give the pilot [his] orders." |

| 18:12 | Radar at Wakkanai picked up KAL 007 for the first time.[138] |

| 18:13:05 | Osipovich: "I see it. I am locked onto the target." |

| 18:13 | General Kornukov: "Chaika" (Call sign for Far East Military District Air Defence Forces). Titovnin: "Yes, sir. He sees [it] on the radar screen, He sees [it] on the screen, He has locked on, he is locked on, he is locked on." |

| 18:13:26 | Osipovich: "The target isn't responding to the call." |

| 18:13 | Titovnin: 805, Is the target's heading 240? |

| 18:13:35 | Osipovich: "Affirmative. The target's heading is 240 degrees." |

| 18:13 | Titovnin: Roger, arm your weapons |

| 18:13 | Osipovich: Turned on |

| 18:14 | Gen Kornukov to Gen. Kamenski: "Comrade General, Kamenski, Good morning. I am reporting the situation. Target 60-65 is over Terpenie Bay [East Coast of Sakhalin] tracking 240, 30 kilometers from the State Border. The fighter from Sokol is 6 kilometers away. Locked on, orders were given to arm weapons. The target is not respondeing to identify. He cannot identify it visually because it is still dark, but he is still locked on."

Gen. Kamenski: "We must find out, maybe it is some civilian craft or God knows who." Kornukov: "What civilian? [It] has flown over Kamchatka! It [came] from the ocean without identification. I am giving the order to attack if it crosses the State border." |

| 18:14:59 | KAL 007 contacted Tokyo air traffic control requesting permission to climb to FL 350 [35,000 feet].[139] |

| 18:14:59 | KAL 007: "Tokyo Radio Korean Air zero zero seven" |

| 18:15 | Titovnin: "Maistrenko Comrade Colonel, that is, Titovnin."

Col. Maistrenko (Operations Duty Officer, Combat Control Center): "Yes". Titovnin: "The commander has given orders that if the border is violated—destroy [the target]." Maistrenko: "...May [be] a passenger [aircraft]. All necessary steps must be taken to identify it." Titovnin: "Identification measures are being taken, but the pilot cannot see. It's dark. Even now it's still dark." Maistrenko: "Well, okay. The task is correct. If there are no lights—it cannot be a passenger [aircraft]." |

| 18:15:03 | Tokyo radio: "Korean Air zero zero seven Tokyo" |

| 18:15:07 | KAL 007: "Korean Air zero zero seven requesting climb three five zero" |

| 18:15:13 | Tokyo radio: "Requesting three five zero?" |

| 18:15:15 | KAL 007: "That is affirmative now maintain at three three zero Korean Air zero zero seven" |

| 18:15:19 | Tokyo radio: "Roger stand by call you back" |

| 18:15:21 | KAL 007: "Roger" |

| 18:15:21 | Flight deck: "Oh my God! This radio is very bad" |

| 18:15:52 | [Audible morse transmission starts] |

| 18:17:44 | KAL 007: "Korean Air zero zero seven Secal" |

| 18:20:11 | Toyko radio: "Korean Air zero zero seven. Clearance Tokyo ATC clears Korean Air zero zero seven climb and maintain flight level 350"[139] |

| 18:20:21 | KAL 007: "Ah roger Korean Air 007 climb and maintain at 350 leaving 330 at this time." |

| 18:20:28 | Tokyo radio: "Tokyo roger." |

| 18:21:35 | Osipovich: "Yes, I'm approaching the target. I'm going in closer." |

| 18:21:35 | Osipovich: "The target's (strobe) light is blinking. I have already approached the target to a distance of about 2 kilometers." |

| 18:21:40 | Osipovich: "The target is at 10,000 metres (33,000 ft)." |

| 18:21:55 | Osipovich: "What are instructions?" |

| 18:22:02 | KAL 007 decreased speed as it climbed, causing the pursuing fighter to draw abeam of it.

Osipovich: "The target is decreasing speed." |

| 18:22:17 | Osipovich: "I am going around it. I'm already moving in front of the target." |

| 18:22:17 | Titovnin: "Increase speed, 805" [call sign of Osipovich's Sukhoi]. |

| 18:22:23 | Osipovich: "I have increased speed." |

| 18:22:23 | Titovnin: "Has the target increased speed, yes?" |

| 18:22:29 | Osipovich: "No, it is decreasing speed." |

| 18:22:29 | Titovnin: "805, open fire on target." |

| 18:22:42 | Osipovich: "It should have been earlier. How can I chase it? I'm already abeam of the target." |

| 18:22:42 | Titovnin: "Roger, if possible, take up a position for attack." |

| 18:22:55 | Osipovich: "Now I have to fall back a bit from the target." |

| 18:21-22 | Kornukov: "Gerasimenko, cut the horesplay at the command post, what is that noise there? I repeat the combat task: fire missiles, fire on target 60-65."

Gerasimenko: "Wilco" Kornukov: "Comply and get Tarasov here. Take control of the Mig-23 from Smirnykh, call sign 163, call sign 163, he is behind the target at the moment. Destroy the target!" Gerasimenko: "Task received. Destroy target 60-65 with missile fire, accept control of fighter from Smirnykh" Kornukov: "Carry out the task, destroy [it]!" |

| 18:22:55 | Gen. Kornukov: "Oh, [expletives] how long does it take him to get into attack position, he is already getting out into neutral waters? Engage afterburner immediately. Bring in the MiG 23 as well... While you are wasting time it will fly right out."[140]

Titovnin: "805, try to destroy the target with cannons." |

| 18:22:56 | The Boeing reports reaching its newly assigned altitude

KAL 007: "Tokyo Radio Korean Air 007 reaching level three five zero".[139] |

| 18:23:37 | Osipovich: "I am dropping back. Now I will try a rocket." |

| 18:23:37 | Titovnin: "Roger." |

| 18:23:49 | MiG 23 (163): "Twelve kilometers to the target. I see both [the Soviet interceptor piloted by Osipovich and KAL 007]." |

| 18:23:37 | Titovnin: "805, approach target and destroy target." |

| 18:24:22 | Osipovich: "Roger, I am in lock-on." |

| 18:24:22 | Titovnin: "805, are you closing on the target?" |

| 18:25:11 | Osipovich: "I am closing on the target, am in lock-on. Distance to target is 8 kilometers." |

| 18:25:11 | Titovnin: "Afterburner. AFTERBURNER, 805!" |

| 18:25:16 | Osipovich: "I have already switched it on." |

| 18:25:16 | Titovnin: "Launch!" |

| 18:25:46 | Osipovich: "Z.G." (Fuel panel light) |

| 18:26:02 | Cockpit: [Sound of explosion?] |

| 18:26:06 | Captain: "What's happened?" |

| 18:26:08 | Co-pilot: "What?" |

| 18:26:10 | Captain: "Retard throttles." |

| 18:26:11 | Co-Pilot: "Engines normal." |

| 18:26:14 | Captain: "Landing gear." |

| 18:26:15 | Cockpit: [Sound of cabin altitude warning] |

| 18:26:17 | Captain: "Landing gear." |

| 18:26:18 | Cockpit: [Sound of altitude deviation warning] |

| 18:26:20 | Osipovich: "I have executed the launch." |

| 18:26 | Kornukov: "Well, what do you hear there?"

Gerasimenko: "He has launched" Kornukov: "I did not understand" Gerasimenko: "He has launched" Kornukov: "He has launched, follow the target, follow the target, withdraw yours from the attack and bring the MiG-23 in there." |

| 18:26:21 | Cockpit: [Sound of autopilot disconnect warning] |

| 18:26:22 | Captain: "Altitude is going up. Altitude is going up. Speed brake is coming out." [Flight Data Recorder will show that speed brake had not deployed] |

| 18:26:22 | Major Osipovich mistakenly (as subsequent Russian real-time military telecommunications show) reports the Boeing is destroyed

Osipovich: "The target is destroyed."[139] |

| 18:26:22 | Titovnin: "Break off attack to the right, heading 360." |

| 18:26:26 | Co-Pilot: "What? What?" |

| 18:26:27 | Osipovich: "I am breaking off attack." |

| 18:26:27 | Cockpit: [Unintelligible] |

| 18:26:29 | Captain: "Check it out." |

| 18:26:33 | Captain: "I am not able to drop altitude." |

| 18:26:33 | MiG-23: "What are (my) instructions?" |

| 18:26:34 | Public Address: "Attention emergency descent" |

| 18:26:38 | Public Address: "Attention emergency descent" |

| 18:26:38 | Crew: "Altitude is going up." |

| 18:26:40 | Crew: "This is not working. This is not working." |

| 18:26:41 | Crew: "Manually." |

| 18:26:42 | Crew: "Cannot do manually." |

| 18:26:42 | Public Address: "Attention emergency descent" |

| 18:26:43 | Cockpit: [Sound of the autopilot disconnect warning] ICAO graphing of Digital Flight Data Recorder tapes will show that autopilot has now been disengaged and manual control begun. KAL 007 now begins descent phase of arc. |