Fructose

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(2R,3S,4R,5R)-2,5-Bis(hydroxymethyl)oxolane-2,3,4-triol

| |

| Other names

D-arabino-Hexulose

Fruit sugar beta-Levulose Levulose | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.303 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| Properties | |

| C6H12O6 | |

| Molar mass | 180.16 g mol−1 |

| Melting point | β-D-fructose: 103°C |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Fructose (also levulose or laevulose) is a simple reducing sugar found in many foods and is one of the three important dietary monosaccharides along with glucose and galactose. Honey, tree fruits, berries, melons, and some root vegetables, such as beets, sweet potatoes, parsnips, and onions, contain fructose, usually in combination with glucose in the form of sucrose. Fructose is also derived from the digestion of granulated table sugar (sucrose), a disaccharide consisting of glucose and fructose.

Crystalline fructose and high-fructose corn syrup are often mistakenly confused as the same product. The former is produced from a fructose-enriched corn syrup which results in a finished product of at least 98% fructose. The latter is usually supplied as a mixture of nearly equal amounts of fructose and glucose.

Chemical properties

Classification and structure

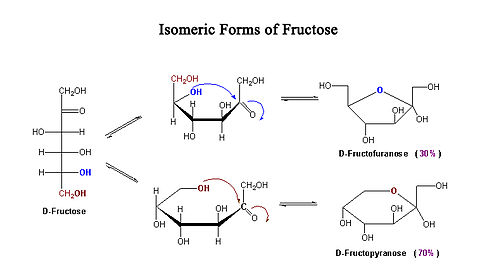

Fructose, also referred to as fruit sugar is a simple monosaccharide with a ketone functional group. Fructose is an isomer of glucose with the same molecular formula (C6H12O6) but with a different structure. Fructose is a 6-carbon polyhydroxyketone. When dissolved in solution, it forms ring structures similar to glucose, which are classified as cyclic hemiketals as opposed to the cyclic hemiacetals formed by aldoses such as glucose. When fructose forms a 5-member ring, the OH group on the fifth carbon atom attaches to the carbonyl group that is on the second carbon atom (D-Fructofuranose). Alternatively, the OH group on the sixth carbon may attach to the carbonyl carbon to form a 6-member ring (D-Fructopyranose). Fructose may be found at equilibrium containing a mixture of 70% fructopyranose and 30% fructofuranose [1]

Chemical reactions

Fructose and fermentation

Fructose may be anaerobically fermented by yeast or bacteria. [2] Yeast enzymes convert sugar (glucose, or fructose) to ethanol and carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide released during fermentation will remain dissolved in water where it will reach equilibrium with carbonic acid unless the fermentation chamber is left open to the air. The dissolved carbon dioxide and carbonic acid produce the carbonation in bottle fermented beverages. [3]

Fructose and maillard reaction

Fructose undergoes the Maillard reaction, non-enzymatic browning, with amino acids. Because fructose exists to a greater extent in the open-chain form than does glucose, the initial stages of the Maillard reaction occurs more rapidly than with glucose. Therefore, fructose potentially may contribute to changes in food palatability, as well as other nutritional effects, such as excessive browning, volume and tenderness reduction during cake preparation, and formation of mutagenic compounds. [4]

Physical and functional properties

Relative sweetness

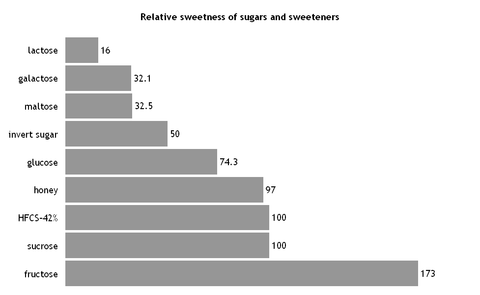

The primary reason that fructose is used commercially in foods and beverages, besides that it is inexpensive compared to sucrose, is because of its relative sweetness. It is the sweetest of all naturally occurring carbohydrates. Fructose is generally regarded as being 1.73 times sweeter than sucrose[5][6] . However, it is the 5-ring form of fructose that is sweeter; the 6-ring form tastes about the same as usual table sugar. Unfortunately, warming fructose leads to formation of the 6-ring form.[7]

Figure 2 Relative sweetness of sugars and sweeteners

The sweetness intensity profile of fructose The sweetness of fructose is perceived earlier than that of sucrose or dextrose, and the taste sensation reaches a peak (higher than sucrose) and diminishes more quickly than sucrose. Fructose can also enhance other flavors in the system[5]

Sweetness synergy Fructose exhibits a sweetness synergy effect when used in combination with other sweeteners. The relative sweetness of fructose blended with sucrose, aspartame, or saccharin is perceived to be greater than the sweetness calculated from individual components[8].

Fructose solubility and crystallization

Fructose has the higher solubility than other sugars and sugar alcohols do. Fructose is therefore difficult to crystallize from an aqueous solution.[5] Sugar mixes containing fructose, such as candies, are softer than those containing other sugars because of the greater solubility of fructose [9].

Fructose hygroscopicity and humectancy Fructose is quicker to absorb moisture and slower to release it to the environment than sucrose, dextrose, or other nutritive sweeteners [8]. Fructose is an excellent humectant and retains moisture for a long period of time even at low relative humidity (RH). Therefore, fructose can contribute to improved quality, better texture, and longer shelf life to the food products in which it is used.[5]

Freezing point Fructose has a greater effect on freezing point depression than disaccharides or oligosaccharides, which may protect the integrity of cell walls of fruit by reducing ice crystal formation. However, this characteristic may be undesirable in soft-serve or hard-frozen dairy desserts.[5]

Fructose and starch functionality in food systems

Fructose increases starch viscosity more rapidly and achieves a higher final viscosity than sucrose because fructose lowers the temperature required during gelatinizing of starch, causing a greater final viscosity [10].

Food sources

The primary food sources of fructose are fruits, vegetables, and honey [11]. Fructose exists in foods either as a free monosaccharide or bound to glucose as the disaccharide, sucrose. Fructose, glucose, and sucrose can all be present in a food; however, different foods will have varying levels of each of these three sugars.

The sugar content of common fruits and vegetables are presented in Table 1. In general, foods that contain free fructose have equal amount of free glucose. In other words, the ratio of fructose to glucose roughly equals 1:1. A value that is above 1 indicates higher proportion of fructose to glucose and vice versa. Some of the fruits have larger proportions of fructose to glucose compared to others. For example, apples and pears contain more than twice as much free fructose as glucose, while apricots contain less than a half of fructose than glucose.

Apple and pear juices are of particular interest to pediatricians due to the juices’ high concentration of free fructose relative to glucose, which can cause diarrhea in children. The cells of the small intestine, enterocytes, have lower affinity for fructose absorption compared with that for glucose and sucrose [12]. Unabsorbed fructose creates higher osmolarity in the small intestine, which draws water into the gastrointestinal tract, resulting in osmotic diarrhea. This phenomenon is discussed in greater details in Health Effects section.

Table 1 also shows the amount of sucrose found in common fruits and vegetables. Sugar cane and sugar beet have a high concentration of sucrose, and are used for commercial preparation of pure sucrose. Extracted cane or beet juices are clarified from the impurities and concentrated by removing excess of water. The end product is 99.9% pure sucrose. Sucrose containing sugars include common white granulated sugar, powdered sugar, as well as brown sugar [13].

Table 1 – Sugar content of selected common plant foods (g/100g)

| Food Item | Total

Carbohydrate |

Total

Sugars |

Free

Fructose |

Free

Glucose |

Sucrose | Fructose /

Glucose Ratio |

Sucrose

as a % of Total Sugars |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruit | |||||||

| Apple | 13.8 | 10.4 | 5.9 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 19.9 |

| Apricot | 11.1 | 9.2 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 5.9 | 0.7 | 63.5 |

| Banana | 22.8 | 12.2 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 20.0 |

| Grapes | 18.1 | 15.5 | 8.1 | 7.2 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| Peach | 9.5 | 8.4 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 4.8 | 0.9 | 56.7 |

| Pear | 15.5 | 9.8 | 6.2 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 8.0 |

| Vegetables | |||||||

| Beet, Red | 9.6 | 6.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 6.5 | 1.0 | 96.2 |

| Carrot | 9.6 | 4.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 70.0 |

| Corn, Sweet | 19.0 | 3.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 64.0 |

| Red Pepper, Sweet | 6.0 | 4.2 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.0 |

| Onion, Sweet | 7.6 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 14.3 |

| Sweet Potato | 20.1 | 4.2 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 0.9 | 60.3 |

| Yam | 27.9 | 0.5 | tr | tr | tr | na | tr |

| Sugar Cane | 13 - 18 | 0.2 – 1.0 | 0.2 – 1.0 | 11 - 16 | 1.0 | 100 | |

| Sugar Beet | 17 - 18 | 0.1 – 0.5 | 0.1 – 0.5 | 16 - 17 | 1.0 | 100 |

Data obtained at http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/search/ [14] All data with a unit of g (gram) are based on 100 g of a food item. The fructose / glucose ratio is calculated by dividing the sum of free fructose plus half sucrose by the sum of free glucose plus half sucrose.

Fructose is also found in the synthetically manufactured sweetener, high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS). Hydrolyzed corn starch is used as the raw material for production of HFCS. Through the enzymatic treatment, glucose molecules are converted into fructose [13]. There are three types of HFCS, each with a different proportion of fructose: HFCS-42, HFCS-55, and HFCS-90. The number for each HFCS corresponds to the percentage of synthesized fructose present in the syrup. HFCS-90 has the highest concentration of fructose, and is typically used to manufacture HFCS-55; HFCS 55 is used as sweetener in soft drinks, while HFCS-42 is used in many processed foods and baked goods.

Commercial sweeteners (carbohydrate content)

| Sugar | Fructose | Glucose | Sucrose | Other Sugars |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Granulated Sugar | (50) | (50) | 100 | 0 |

| Brown Sugar | 1 | 1 | 97 | 1 |

| HFCS-42 | 42 | 53 | 0 | 5 |

| HFCS-55 | 55 | 41 | 0 | 4 |

| HFCS-90 | 90 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Honey | 50 | 44 | 1 | 5 |

| Maple Syrup | 1 | 4 | 95 | 0 |

| Molasses | 23 | 21 | 53 | 3 |

| Corn Syrup | 0 | 35 | 0 | 0 |

Data obtained from Kretchmer, N. & Hollenbeck, CB (1991). Sugars and Sweeteners, Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, Inc. [13] for HFCS, and USDA for fruits and vegetables and the other refined sugars. [15]

Cane and beet sugars have been used as the major sweetener in food manufacturing for centuries. However, with the development of HFCS, a significant shift occurred in the type of sweetener consumption. As seen in Figure 3, this change happened in the 70’s. Contrary to the popular belief, however, with the increase of HFCS consumption, the total fructose intake has not dramatically changed. Granulated sugar is 99.9% pure sucrose, which means that it has equal ratio of fructose to glucose. The most commonly used HFCS, 42 and 55, have about equal ratio of fructose to glucose, with minor differences. HFCS has simply replaced sucrose as a sweetener. Therefore, despite the changes in the sweetener consumption, the ratio of glucose to fructose intake has remained relatively constant [16].

Figure 3 Adjusted consumption of refined sugar per capita in the U.S.

Fructose digestion and absorption in humans

Fructose exists in foods as either a monosaccharide (free fructose) or as a disaccharide (sucrose). Free fructose does not undergo digestion; however when fructose is consumed in the form of sucrose, digestion occurs entirely in the upper small intestine. As sucrose comes into contact with the membrane of the small intestine, the enzyme sucrase catalyzes the cleavage of sucrose to yield one glucose and fructose unit. Fructose, passes through the small intestine, virtually unchanged, then enters the portal vein and is directed toward the liver.

Figure 4 Hydrolysis of sucrose to glucose and fructose by sucrase

The mechanism of fructose absorption in the small intestine is not completely understood. Some evidence suggests active transport, because fructose uptake has been shown to occur against a concentration gradient. [17] However, the majority of research supports the claim that fructose absorption occurs on the mucosal membrane via facilitated transport involving GLUT5 transport proteins. Since the concentration of fructose is higher in the lumen, fructose is able to flow down a concentration gradient into the enterocytes, assisted by transport proteins. Fructose may be transported out of the enterocyte across the basolateral membrane by either GLUT2 or GLUT5, although the GLUT2 transporter has a greater capacity for transporting fructose and therefore the majority of fructose is transported out of the enterocyte through GLUT2.

Figure 5 Intestinal sugar transport proteins

Capacity and rate of absorption

The absorption capacity for fructose in monosaccharide form ranges from less than 5g to 50g and adapts with changes in dietary fructose intake. Studies show the greatest absorption rate occurs when glucose and fructose are administered in equal quantities [18]. When fructose is ingested as part of the disaccharide sucrose, absorption capacity is much higher because fructose exists in a 1:1 ratio with glucose. It appears that the GLUT5 transfer rate may be saturated at low levels and absorption is increased through joint absorption with glucose [19]. One proposed mechanism for this phenomenon is a glucose-dependent cotransport of fructose. In addition, fructose transfer activity increases with dietary fructose intake. The presence of fructose in the lumen causes increased mRNA transcription of GLUT5, leading to increased transport proteins. High fructose diets have been shown to increase abundance of transport proteins within 3 days of intake. [20]

Malabsorption

Several studies have measured the intestinal absorption of fructose using hydrogen breath test[21] [22] [23] [24] . These studies indicate that fructose is not completely absorbed in the small intestine. When fructose is not absorbed in the small intestine, it is transported into the large intestine, where it is fermented by the colonic flora. Hydrogen is produced during the fermentation process and dissolves into the blood of the portal vein. This hydrogen is transported to the lungs, where it is exchanged across the lungs and is measurable by the hydrogen breath test. The colonic flora also produces carbon dioxide, short chain fatty acids, organic acids, and trace gases in the presence of unabsorbed fructose [25]. The presence of gases and organic acids in the large intestine causes gastrointestinal symptoms such as bloating, diarrhea, flatulence, and gastrointestial pain [26]. Exercise can exacerbate these symptoms by decreasing transit time in the small intestine, resulting in a greater amount of fructose being emptied into the large intestine[27].

Fructose metabolism

All three dietary monosaccharides are transported into the liver by the GLUT 2 transporter [28]. Fructose and galactose are phosphorylated in the liver by fructokinase (km = 0.5 mM) and galactokinase (km = 0.8 mM). By contrast, glucose tends to pass through the liver (km of hepatic glucokinase = 10 mM) and can be metabolised anywhere in the body. Uptake of fructose by the liver is not regulated by insulin.

Fructolysis

Fructolysis occurs in two steps. First, trioses, dihydroxyacetone (DHAP) and glyceraldehyde are synthesized. Second, trioses are metabolized either in the gluconeogenic pathway for glycogen replenishment and/or complete metabolism in the fructolytic pathway to pyruvate, which after conversion to acetyl-CoA enters the Krebs cycle, and is converted to citrate and subsequently directed toward ’’de novo’’ synthesis of the free fatty acid palmitate [29].

Metabolism of fructose to DHAP and glyceraldehyde

The first step in the metabolism of fructose is the phosphorylation of fructose to fructose 1-phosphate by fructokinase, thus trapping fructose for metabolism in the liver. Fructose 1-phosphate then undergoes hydrolysis by aldolase B to form DHAP and glyceraldehydes; DHAP can either be isomerized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate by triosephosphate isomerase or undergo reduction to glycerol 3-phosphate by glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. The glyceraldehyde produced may also be converted to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate by glyceraldehyde kinase or converted to glycerol 3-phosphate by glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. The metabolism of fructose at this point yields intermediates in the gluconeogenic and fructolytic pathways leading to glycogen synthesis as well as fatty acid and triglyceride synthesis.

Synthesis of glycogen from DHAP and glyceraldehyde 3 phosphate

The resultant glyceraldehyde formed by aldolase B then undergoes phosphorylation to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate. Increased concentrations of DHAP and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate in the liver drive the gluconeogenic pathway toward glucose and subsequent glycogen synthesis. It appears that fructose is a better substrate for glycogen synthesis than glucose and that glycogen replenishment takes precedence over triglyceride formation [30]. Once liver glycogen is replenished, the intermediates of fructose metabolism are primarily directed toward triglyceride synthesis.

Figure 6 Metabolic conversion of fructose to glycogen in the liver

Synthesis of triglyceride from DHAP and glyceraldehyde 3 phosphate

Carbons from dietary fructose are found in both the free fatty acid and glycerol moieties of plasma triglycerides. High fructose consumption can lead to excess pyruvate production, causing a buildup of Krebs cycle intermediates [29]. Accumulated citrate can be transported from the mitochondria into the cytosol of hepatocytes, converted to acetyl CoA by citrate lyase and directed toward fatty acid synthesis [29]; [31]. Additionally, DHAP can be converted to glycerol 3-phosphate as previously mentioned, providing the glycerol backbone for the triglyceride molecule [31]. Triglycerides are incorporated into very low density lipoproteins (VLDL), which are released from the liver destined toward peripheral tissues for storage in both fat and muscle cells.

Figure 7 Metabolic conversion of fructose to triglyceride in the liver

Health effects

Fructose absorption occurs via the GLUT-5[32] (fructose only) transporter, and the GLUT2 transporter, for which it competes with glucose and galactose. A deficiency of GLUT 5 may result in excess fructose carried into the lower intestine.[citation needed] There, it can provide nutrients for the existing gut flora, which produce gas. It may also cause water retention in the intestine. These effects may lead to bloating, excessive flatulence, loose stools, and even diarrhea depending on the amounts eaten and other factors.

Excess fructose consumption has been hypothesized to be a contributing cause of insulin resistance, obesity,[33] elevated LDL cholesterol and triglycerides, leading to metabolic syndrome[34]. Short-term tests, lack of dietary control, and lack of a non-fructose consuming control group are all confounding factors in human experiments. However, there are now a number of reports showing correlation of fructose consumption to obesity,[35][36] especially central obesity which is thought to be the most dangerous kind of obesity.[citation needed]

There is a concern with Type 1 diabetes patients and the apparent low GI (glycemic index) of fructose. Fructose gives as high a blood sugar spike as that obtained with glucose. In fact, the GI measurement applies only to glucose containing foods (eg, those with high-starch content). The basic GI measurement technique is somewhat confusing. This is because the body's response to glucose is "standardized" with 50g of ingested glucose, while the GI researchers use 50g of digestible carbohydrate (not necessarily glucose) as its reference standard. Although all simple sugars have nearly identical chemical formulae, each has distinct chemical properties. This can be illustrated with pure fructose. A journal article reports that, "...fructose given alone increased the blood glucose almost as much as a similar amount of glucose (78% of the glucose-alone area)".[37][38][39][39][40]

A study in mice suggests that fructose increases the risk of obesity.[41]

One study concluded that fructose "produced significantly higher fasting plasma triacylglycerol values than did the glucose diet in men" and "...if plasma triacylglycerols are a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, then diets high in fructose may be undesirable".[42] Bantle et al. "noted the same effects in a study of 14 healthy volunteers who sequentially ate a high-fructose diet and one almost devoid of the sugar."[43]

Studies that have compared high fructose corn syrup (an ingredient in nearly all soft drinks sold in the US) to sucrose (common table sugar) find that most measured physiological effects are equivalent. For instance, Melanson et al. (2006), studied the effects of HFCS and sucrose sweetened drinks on blood glucose, insulin, leptin, and ghrelin levels. They found no significant differences in any of these parameters.[44] This is not surprising since sucrose is a disaccharide which digests to 50% glucose and 50% fructose; while the high fructose corn syrup most commonly used on soft drinks is 55% fructose. The difference between the two lies in the fact that HFCS contains little sucrose, the fructose and glucose being independent moities.

Fructose is often recommended for diabetics because it does not trigger the production of insulin by pancreatic ß cells, probably because ß cells have low levels of GLUT5 [45][46][47]. Fructose has a very low glycemic index of 19 ± 2, compared with 100 for glucose and 68 ± 5 for sucrose.[48] Fructose is also seventy-three percent sweeter than sucrose (see 2.1 Relative Sweetness) at room temperature, so diabetics can use less of it. Studies show that fructose consumed before a meal may even lessen the glycemic response of the meal.[49] Its sweetness changes at higher temperatures, so its effects in recipes are not equivalent to sucrose (ie, table sugar).

"The medical profession thinks fructose is better for diabetics than sugar," says Meira Field, Ph.D., a research chemist at United States Department of Agriculture, "but every cell in the body can metabolize glucose. However, all fructose must be metabolized in the liver. The livers of the rats on the high fructose diet looked like the livers of alcoholics, plugged with fat and cirrhotic."[50] This is not entirely true as a few other tissues (eg, sperm cells and some intestinal cells) do use fructose directly, though in less metabolically significant amounts.

Fructose is a reducing sugar, as are all monosaccharides. The spontaneous chemical reaction of simple sugar molecules to proteins, known as glycation, is thought to be a significant cause of damage in diabetics. Fructose appears to be equivalent to glucose in this regard and so does not seem to be a better answer for diabetes for this reason alone, save for the smaller quantities required to achieve equivalent sweetness in some foods.[51] This may be an important contribution to senescence and many age-related chronic diseases.[52]

Fructose is used as a substitute for sucrose (composed of one unit each of fructose and glucose linked together with a relatively weak glycosidic bond) because it is less expensive for a given degree of sweetness and has little effect on measured blood glucose levels. Often, fructose is consumed as high fructose corn syrup, which is corn syrup (glucose) that has been enzymatically treated by the enzyme glucose isomerase to increase the concentration of fructose. This enzyme converts a portion of the glucose into fructose thus making it taste sweeter. This is done to such a degree as to yield corn syrup with an equivalent sweetness to sucrose by weight (the chief sugar in corn syrup is the significantly less sweet glucose). While most carbohydrates have around the same amount of calories, fructose is sweeter than others and manufacturers can use less of it to get the same result. The free fructose present in fruits, their juices, and honey is responsible for the sometimes intense sweetness of these natural sugar sources.

Unlike glucose, fructose is almost entirely metabolized in the liver. "When fructose reaches the liver," says Dr. William J. Whelan, a biochemist at the University of Miami School of Medicine, "the liver goes bananas and stops everything else to metabolize the fructose." Eating fructose as compared to glucose results in lower circulating insulin (pancreatic beta cell insulin release is controlled only by blood glucose levels) and leptin levels, and attenuation in the suppression of ghrelin postprandially.[53] These hormones are implicated in the control of appetite and satiety, and it is suspected that eating large amounts of fructose increases the likelihood of weight gain.[54]

Excessive fructose consumption is also believed to contribute to the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.[55]

It has been suggested in a recent British Medical Journal study that high consumption of fructose is even linked to gout. Cases of gout have risen in recent years, despite commonly being thought of as a Victorian disease, and it is suspected that the fructose found in soft drinks (eg, carbonated beverages) and other sweetened drinks is the reason for this.[56][57]

See also

- DMF (potential fructose-based biofuel)

- Fructose intolerance

- Fructose malabsorption

- Fructan (fructose polymer)

- Galactose

- Glucose

- Glycation

- High fructose corn syrup

- Hyperuricemia

- Seliwanoff's test

- Sucrose

- Sugars in wine

- Agave syrup

References

- ^ Template:Institute of Organic Chemistry

- ^ McWilliams, Margaret. Foods: Experimental Perspectives, 4th Edition.

- ^ Template:Last=Keusch

- ^ Dills, WL (1993). "Protein fructosylation: Fructose and the Maillard reaction". Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 58: 779–787.

- ^ a b c d e Hanover, LM (1993). "Manufacturing, composition, and application of fructose". Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 58: 724s-732.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Oregon State University. "Sugar Sweetness". Last accessed May 5, 2008. http://food.oregonstate.edu/sugar/sweet.html

- ^ Fructose in our diet: http://www.medbio.info/Horn/Time%201-2/carbohydrate_metabolism.htm last visited 2008-12-28

- ^ a b Nabors, LO (2001). "American Sweeteners": 374–375.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ McWilliams, Margaret (2001). Foods: Experimental Perspectives, 4th Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ : Prentice Hall.

- ^ White, DC (1990). "Predicting gelatinization temperature of starch/sweetener system for cake formulation by differential scanning calorimetry I. Development of a model". Cereal Foods Wold. 35: 728–731.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Park, KY (1993). "Intakes and food sources of fructose in the United States". 58: 737S–747S.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Text "American Journal of Clinical Nutrition" ignored (help) - ^ Riby, JE (1993). "Fructose absorption". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 58: 748S–753S.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Kretchmer, N (1991). "Sugars and Sweeteners". CRC Press, Inc.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Template:Url=http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/search/

- ^ Template:Url=http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/search/

- ^ Guthrie, FJ (2000). "Food sources of added sweeteners in the diets of Americans". Journals of American Dietetic Association. 100: 43–51. doi:10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00018-3.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Stipanuk, Marsha H (2006). "Biochemical, Physiological, and Molecular Aspects of Human Nutrition, 2nd Edition". W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Fujisawa, T (1991). "Intestinal absorption of fructose in the rat". Gastroenterology. 101: 360–367. PMID 206591.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ushijima, K (1991). "Absorption of fructose by isolated small intestine of rats is via a specific saturable carrier in the absence of glucose and by the disaccharidase-related transport system in the presence of glucose". Journal of Nurtition. 125: 2156–2164. PMID 7643250.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ferraris, R (2001). "Dietary and developmental regulation of intestinal sugar transport". Journal of Biochemistry. 360: 265–276. doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3600265. PMID 11716754.

- ^ Beyer, PL (2005). "Fructose intake at current levels in the United States may cause gastrointestinal distress in normal adults". J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 105: 1559–1566. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2005.07.002.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ravich, WJ (1983). "Fructose: incomplete intestinal absorption in humans". Gastroenterology. 84: 26–29.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Riby, JE (1993). "Fructose absorption". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 58: 748S–753S.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rumessen, JJ (1986). "Absorption capacity of fructose in healthy adults, comparison with sucrose and its constituent monosaccharides". Gut. 27: 1161–1168. doi:10.1136/gut.27.10.1161. PMID 3781328.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Skoog, SM (2004). "Dietary fructose and gastrointestinal symptoms: a review". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 99: 2046–50. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40266.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Beyer, PL (2005). "Fructose intake at current levels in the United States may cause gastrointestinal distress in normal adults". J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 105: 1559–66. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2005.07.002.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Fujisawa, T (1993). "The effect of exercise on fructose absorption". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 58: 75–9.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Quezada-Calvillo, R (2006), Carbohydrate Digestion and Absorption, Missouri: Saunders, Elsevier, pp. 182–185, ISBN 141600209X

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coathors=ignored (help) - ^ a b c McGrane, MM (2006), Carbohydrate metabolism: Synthesis and oxidation, Missouri: Saunders, Elsevier, pp. 258–277, ISBN 141600209X

- ^ Parniak, MA (1988). "Enhancement of glycogen concentrations in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes exposed to glucose and fructose". Biochemical Journal. 251: 795–802.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coathors=ignored (help) - ^ a b Sul, HS (2006), Metabolism of Fatty Acids, Acylglycerols, and Sphingolipids, Missouri: Saunders, Elsevier, pp. 450–467, ISBN 141600209X

- ^ Buchs, AE (1998). "Characterization of GLUT5 domains responsible for fructose transport". Endocrinology. 139: 827–31. doi:10.1210/en.139.3.827. PMID 12399260.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Elliott SS, Keim NL, Stern JS, Teff K, Havel PJ (2002). "Fructose, weight gain, and the insulin resistance syndrome". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 76 (5): 911–22. PMID 12399260.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Basciano H, Federico L, Adeli K (2005). "Fructose, insulin resistance, and metabolic dyslipidemia". Nutrition & Metabolism. 2 (5): 5. doi:10.1186/1743-7075-2-5. PMID PMC552336.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmid=value (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Lustig RH (2006). "Childhood obesity: behavioral aberration or biochemical drive? Reinterpreting the First Law of Thermodynamics". Nature clinical practice. Endocrinology & metabolism. 2 (8): 447–58. doi:10.1038/ncpendmet0220. PMID 16932334.

- ^ Isganaitis E, Lustig RH (2005). "Fast food, central nervous system insulin resistance, and obesity". Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25 (12): 2451–62. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000186208.06964.91. PMID 16166564.

- ^ Hughes TA, Atchison J, Hazelrig JB, Boshell BR (1989). "Glycemic responses in insulin-dependent diabetic patients: effect of food composition". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 49 (4): 658–66. PMID 2929488.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wylie-Rosett, Judith (2004). "Carbohydrates and Increases in Obesity: Does the Type of Carbohydrate Make a Difference?". Obesity Res. 12: 124S–129S. doi:10.1038/oby.2004.277.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Havel PJ (2001). "Peripheral signals conveying metabolic information to the brain: short-term and long-term regulation of food intake and energy homeostasis". Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood). 226 (11): 963–77. PMID 11743131.

- ^ Dennison BA, Rockwell HL, Baker SL (1997). "Excess fruit juice consumption by preschool-aged children is associated with short stature and obesity". Pediatrics. 99 (1): 15–22. PMID 8989331.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jürgens H, Haass W, Castañeda TR; et al. (2005). "Consuming fructose-sweetened beverages increases body adiposity in mice". Obes. Res. 13 (7): 1146–56. doi:10.1038/oby.2005.136. PMID 16076983.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bantle JP, Raatz SK, Thomas W, Georgopoulos A (2000). "Effects of dietary fructose on plasma lipids in healthy subjects". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 72 (5): 1128–34. PMID 11063439.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Enerex.ca | Whey Protein and Fructose, an Unhealthy Combination

- ^ Melanson, K. (2006). "Eating Rate and Satiation". Obesity Society (NAASO) 2006 Annual Meeting, October 20-24,Hynes Convention Center, Boston, Massachusett. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.02452<o:p>.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help) - ^ A. M. Grant, M. R. Christie, S. J. Ashcroft (1980). "Insulin Release from Human Pancreatic Islets in Vitro". Diabetologia. 19 (2): 114–117. doi:10.1007/BF00421856. PMID 6998814.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ D. L. Curry (1989). "Effects of Mannose and Fructose on the Synthesis and Secretion of Insulin". Pancreas. 4 (1): 2–9. doi:10.1097/00006676-198902000-00002. PMID 2654926.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Y. Sato, T. Ito, N. Udaka; et al. (1996). "Immunohistochemical Localization of Facilitated-Diffusion Glucose Transporters in Rat Pancreatic Islets". Tissue Cell. 28 (6): 637–643. doi:10.1016/S0040-8166(96)80067-X. PMID 9004533.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kaye Foster-Powell, Susanna H. A. Holt, and Janette C. Brand-Miller. July 2002. International Table of Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load Values: 2002. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 76(1):5-56

- ^ Patricia M. Heacock, Steven R. Hertzler and Bryan W. Wolf. September 2002. Fructose Prefeeding Reduces the Glycemic Response to a High-Glycemic Index, Starchy Food in Humans. The Journal of Nutrition 132(9):2601-2604

- ^ Forristal, Linda (2001). "The Murky World of High-Fructose Corn Syrup". Weston A. Price Foundation.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ McPherson, JD (1988). "Role of fructose in glycation and cross-linking of proteins. PMID 3132203". Biochemistry. 27 (5): 1901–7. doi:10.1021/bi00406a016.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Levi, B (1998). Fulltext "Long-term fructose consumption accelerates glycation and several age-related variables in male rats. PMID 9732303". J Nutr. 128: 1442–9.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Teff, KL (2004). "Dietary fructose reduces circulating insulin and leptin, attenuates postprandial suppression of ghrelin, and increases triglycerides in women". J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 89 (6): 2963–72. doi:10.1210/jc.2003-031855. PMID 15181085.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Swan, Norman; Lustig, Robert H. "ABC Radio National, The Health Report, The Obesity Epidemic". Retrieved 2007-07-15.

- ^ Ouyang X, Cirillo P, Sautin Y; et al. (2008). "Fructose consumption as a risk factor for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease". J. Hepatol. 48 (6): 993–9. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2008.02.011. PMID 18395287.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Gout surge blamed on sweet drinks". BBC News. 2008-02-01.

- ^ Johnson, Richard Joseph (2008). The Sugar Fix : The High-Fructose Fallout That is Making You Fat and Sick. US: Rodale. p. 304. ISBN 10 1-59486-665-1.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help); External link in|publisher=|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

- Fructose

- Carbohydrate metabolism

- [1] Hereditary Fructose Intolerance

- [2] Sugars4Kids