North American river otter

nikki rocks

| North American River Otter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | L. canadensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Lontra canadensis (Schreber, 1777)

| |

| |

The North American River Otter (Lontra canadensis), also known as the Northern River Otter or the Common Otter, is a semi-aquatic mammal endemic to the North American continent, found in and along its waterways and coasts. An adult river otter can weigh between 5 and 14 kg (11 and 30 lb). The river otter is protected and insulated by a thick, water-repellent coat of fur.

The river otter, a member of the weasel family, is equally versatile in the water and on land. The otter establishes a burrow close to the water's edge in river, lake, swamp, coastal shoreline, tidal flat, or estuary ecosystems. Their dens have many tunnel openings—one of which generally allows the otter to enter and exit the body of water. Female otters give birth in these underground burrows, producing litters of one to six young.

North American river otters hunt during the night and prey upon the species that are the most readily accessible. Fishes are a favored food among the otters, but they also consume various amphibians, turtles, and crayfish. There have been instances of river otters eating small mammals, including beavers. The species can be preyed upon by both terrestrial and aquatic animals alike.

The range of the North American river otter has been significantly reduced by habitat loss, beginning with the European colonization of North America. However, in some regions their population is controlled to allow the trapping and harvesting of otters for their pelts. River otters are very susceptible to environmental pollution, which is a likely factor in the continued decline of their numbers. A number of reintroduction projects have been initiated to help stabilize the reduction in the overall river otter population.

Taxonomy and evolution

The North American river otter was first described by German naturalist Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber in 1777.[2] The mammal was identified as a species of otter and has a variety of common names including North American river otter, Northern river otter, common otter and, simply, river otter.[2] Other documented common names are American otter, Canada otter, Canadian otter, Fish otter, Land otter, Nearctic river otter, and Prince of Wales otter.[3]

The river otter was first classified in the genus Lutra: Lutra was the early European name. The species name was Lutra canadensis.[2] The species epithet canadensis means of Canada.[4] There were several geographic sub-species recognized including Lutra canadensis evexa, Lutra canadensis mira, Lutra canadensis preblei, Lutra canadensis kodiacensis (Kodiak Islands, Alaska), Lutra canadensis periclyzomae (British Columbia), Lutra canadensis mira (Alaska, British Columbia), Lutra canadensis pacifica (Alaska, Canada, northern USA, south to central California, northern Nevada, and northeastern Utah), Lutra canadensis canadensis (Eastern Canada, USA, Newfoundland), Lutra canadensis sonora (USA, Mexico), Lutra canadensis lataxina (USA), Lutra canadensis annectens (Mexico, south through Central America and South America west of the Andes as far as Peru), Lutra canadensis enudris (Northern South America, throughout the Amazon Basin and rivers of eastern Brazil, Argentina, Trinidad), Lutra canadensis longicaudis (Paraguay, Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay), and Lutra canadensis provocax (Chile, Argentina).[5][6] In a new classification, the species is called Lontra canadensis, where the genus Lontra includes all the New World river otters.[7] Molecular biology techniques have been used to determine that the lineages leading to the river otter and the giant otter diverged in the Miocene epoch (23.03 to 5.33 million years ago), which is "much earlier" than indicated in the fossil record.[8] While fossils of a giant river otter dating back 3.5 million years ago have been found in the US midwest, the modern river otter is closely related to the otters of Europe and did not appear in North America until about 1.9 million years ago.[9] The earliest known fossil of Lontra canadensis was found in the US midwest and is from the Irvingtonian stage (the geologic timescale that spans the period 1,800,000 to 300,000 years ago).[10] The oldest fossil record of an Old World river otter comes from the late Pliocene epoch (3.6 to 1.8 million years ago).[11] The New World river otters originated from the Old World river otters after a migration across the Bering Land Bridge, which existed off and on between 1.8 million to 10,000 years ago. The otters migrated to North America and southwards again across the Panamanian Land Bridge, which formed 3 million years ago.[3]

Physical characteristics

The North American river otter is a stocky animal of 5 to 14 kg (11–30 lb) with short legs, a muscular neck no smaller than the head, and an elongated body that is broadest at the hips.[10] Its body length ranges from 0.66 m (26 in) to 1.07 m (42 in).[12] About one-third of the animal's length is comprised of a long, tapered, tail.[10] Tail length ranges from 30 to 50 cm (11.75 to 19.75 in).[12] It differs from the European otter by its longer neck, narrower visage, the smaller space between the ears and its shorter tail.[13]

A broad muzzle is found on the river otter's flat head, and the ears are round and inconspicuous. The rhinarium is bare with an obtuse triangular projection. Eyes of the animal are small and placed anteriorly. A short, broad rostrum for exhaling and a long, broad cranium define the relatively flat skull.[10] The river otter's nostrils and ears close during submersion, inhibiting water from entering these regions.[10] Its vibrissae, or whiskers, are long and thick, enhancing sensory perception underwater and on land.[10]

The fur of the species is short (guard hairs average 23.8 mm) and very dense, with a density of approximately 57,833 hairs/cm2 in the midback section. The pelage has a high luster and varies from light brown to black. The throat, chin, and lips are grayer than the rest of the body. Fur of senescent river otters may become white-tipped, and rare albinos may occur.[10]

Sexual dimorphism exists among the river otters.[14] Males are, on average, 5% larger than females. In Idaho, juvenile, yearling, and adult males averaged 8, 11, and 17% heavier, respectively, than females of the same age. A clinical reduction in size may exist from north to south along the Pacific coast, but not from east to west.[10]

North American river otters usually live to 21 years of age in captivity,[14] but they can reach 25 years of age.[10] However, they normally live about 8 to 9 years in the wild,[14] but are capable of living up to 13 years of age.[10]

Form and function

The river otter is physically well-equipped for aquatic life. The ears are short, the neck is the same diameter as the head, the legs are short and powerful, the toes are fully webbed, and the tail (one-third of body length) is tapered. These qualities give the river otter a streamlined profile in water, but reduce agility on land. The smell and hearing abilities of the river otter are acute. The otter has a delicate sense of touch in the paws in addition to great dexterity.[10]

The lungs of the river otter are triangular in outline, with the apex directed cranially. The right lung is 19.3% larger than the left and has four lobes compared with two for the left. Reduced lobulation of the lungs are presumed to be an adaption to aquatic life. In addition, the length of the trachea of the river otter is intermediate between that of terrestrial carnivores and marine mammals. The mean tracheal length of the river otter is 15.3 cm, or 23.2% of the body length. A shorter trachea may improve air exchange and increase lung ventilation in diving mammals.[10]

Most mustelids, including otters, have specialized teeth, including sharp canines and carnassials that inflict lethal bites to prey. Also, river otters have large molars used for degenerating hard objects, such as the shells of molluscs.[15] An adult river otter has a total of 36 teeth. Additional premolars may be present.[10] The dental formula of an adult river otter is:

| Dentition |

|---|

| 3.1.4.1 |

| 3.1.3.2 |

Behavior

The river otter is active year-round and is most active at night and during crepuscular hours. The otter becomes much more nocturnal in the spring, summer, and fall seasons and it becomes more diurnal during winter. The otters may emigrate as a result of food shortages or environmental conditions, but they do not migrate annually.[10]

Movement

Otters swim by quadrupedal paddling, forelimb paddling, alternate hind-limb paddling, simultaneous hind-limb paddling, or body and tail dorsoventral undulation. The tail, which is stout and larger in surface area than the limbs, is used for stability while swimming and for short bursts of rapid propulsion. While swimming at the surface, the dorsal portion of the river otter's head, including nostrils, ears, and eyes, is exposed above water. The river otter must remain in motion to maintain its position at the surface.[10]

On land, the river otter can walk, run, bound, or slide. Foot falls during walking and running follow the sequence of left limb, right limb, right limb, left limb. During walking, the limbs are moved in a plane parallel to the long axis of the body. Bounding is the result of simultaneous lifting of the limbs off the ground. As the front feet make contact with the ground, the back feet are lifted and land where the front paws first contacted the ground, producing a pattern of tracks in pairs typical of most mustelids. Sliding occurs mostly on even surfaces of snow or ice, but can also occur on grassy slopes and muddy banks. Sliding across snow and ice is a rapid and efficient means of travel, and otters traveling over mountain passes, between drainages, or descending from mountain lakes often slide continuously for several hundred meters. During winter, the river otters heavily utilize openings in the ice, and may excavate passages in beaver dams for accessing open water.[10]

North American river otters are highly mobile and have the capacity of traveling up to 42 km in one day. Daily movements of yearling males and females in Idaho, averaged, respectively, 4.7 and 2.4 km in spring, 5.1 and 4.0 km in summer, and 5.0 and 3.3 km in autumn. Daily movements of family groups averaged 4.7, 4.4, and 2.4 km in spring, summer, and winter, respectively. Both males and family groups travel drastically less during winter.[10]

Playing

Play behavior is well-developed in North American river otters. Play is made up of sliding, chasing one’s own tail, swimming, juggling sticks or pebbles, rolling around in the grass or snow, wrestling, and playing with captured prey or with other river otters. Playful behavior was found in only 6% of 294 observations in a study in Idaho, and was limited mostly to immature otters.[10]

Hunting

Prey are captured with a quick lunge from ambush or, more rarely, after a sustained chase. River otters can remain underwater for nearly 4 minutes, swim at speeds approaching 11 km/h, dive to depths nearing 20 meters, and travel up to 400 meters while underwater. Several river otters may even cooperate while fishing. Small fish are eaten at the surface but larger ones are taken to the shore to be consumed. Live fish are typically eaten from the head. River otters dry themselves and uphold the insulative quality of their fur by frequent rubbing and rolling on grass, bare ground, and logs. The river otter can be trained by humans to catch and retrieve fish, ducks (Anatidae), and pheasants (Phasianus colchicus) from land or water.[10] Otter-fishing originated and has longest been practiced in Asia. China, Malaya, and India were the countries to make the most use of the otter. Among these countries, the Chinese seem to have been the first people to domesticate the otter and use it to catch fishes.[16]A highly active predator, the river otter has adapted to hunting in water, and eats aquatic and semi-aquatic animals. The vulnerability and seasonal availability of prey animals mainly governs the food habits and prey choices of the river otter.[17] This availability is influenced by the following factors: detectability and mobility of the prey; habitat availability for the various prey species; environmental factors, such as water depth and temperature; and seasonal changes in prey supply and distribution in correspondence with otter foraging habitat.[18][19] The diet of the river otter can be deduced by analyzing either scat obtained in the field,[20] or gut contents removed from trapped otters.[21] Fishes are the primary component of the river otter's diet throughout the year.[22] Every study done on the food habits of the river otter has identified varying fish species as being the primary component of its diet. For instance, an Alberta, Canada study involved the collection and analysis of 1,191 samples of river otter scats collected during each season.[23] Fish remnants were found present in 91.9% of the scat samples. Moreover, a western Oregon study revealed that fish remains were present in 80% of 103 digestive tracts that had been examined.[22] Crustaceans (crayfish),where regionally available, are the second most important prey for otters. Crustaceans may even be consumed more than fishes. For example, a study conducted in a central California marshland indicated that crayfish formed nearly 100% of the river otter's diet at certain times of the year.[24] However, river otters, as foragers, will immediately take advantage of other prey when readily obtainable.[25] Other prey consumed by river otters includes fruits,[26] reptiles and amphibians, birds, aquatic insects, small mammals, and mollusks.[17] River otters are not scavengers; they avoid consuming carrion.[19] Otters do not dramatically reduce prey populations. When a copious supply of food dwindles or other prey become available, otters either translocate to a new location or convert their dietary choices to the most adequate prey.[15] Although other prey species are of temporary significance to the river otter, the deciding factor as to if an the river otter can establish itself as a permanent resident of one location is the year-round availability of fish.[15]

There are reports of photographs of retrieving otters that were used by hunters near Butte, Nebraska.

Social structure

North American river otters are more social than most mustelids. Throughout most freshwater systems, the basic social group of the river otters is the family, consisting of an adult female and her progeny. Although rare, adult males may establish groups ranging in size from less than or equal 10 to as many as 17 individuals. In coastal areas, males may remain gregarious even during the estrous period of females. Family groups may include helpers, which can be made up of unrelated adults, yearlings, or juveniles. On occasion, groups of unrelated juveniles are observed. River otters that live in groups hunt and travel together, use the same dens, resting sites, and latrines, and perform allogrooming. In freshwater systems, groups occur most often in autumn and during early winter. From mid-winter through the breeding season, river otters move and den alone. River otters are not territorial, but individual otters of different groups portray mutual avoidance. Home ranges of males are larger than those of females, and both sexes exhibit intra- and intersexual overlap of their domains.[10]

Communication

Communication among North American river otters is accomplished mainly by olfactory and auditory signals. Scent marking is imperative for intergroup communication. The river otter scent-marks with feces, urine, and possibly anal sac secretions. Musk from the scent glands may also be secreted when otters are frightened or angry.[10]

The river otters can produce a snarling growl or hissing bark when bothered and a shrill whistle when in pain. When at play or traveling, they sometimes give off a low purring grunt. The alarm call, given by an otter when shocked or distressed by potential danger, is an explosive snort, made by expelling air through the nostrils. River otters also may use a birdlike chirp for communication over longer distances, but the most common sound heard among a group of otters is low-frequency chuckling.[10]

Reproduction and life cycle

North American river otters are polygynous.[10] Females usually do not reproduce until 2 years of age, although yearlings produce offspring on occasion. Males are sexually mature at 2 years of age.[1] The number of corpora lutea increases directly with age.[10]

River otters typically breed from December to April. Copulation among river otters lasts from 16–73 minutes and may occur in water or on land. During the breeding, the male grabs the female by the neck with his teeth. Copulation is vigorous, and is interrupted by periods of rest. Females may caterwaul during or shortly after mating. Females are in heat for 42–46 days, and true gestation lasts 61–63 days. Because the otters delay implantation for at least 8 months, the interval between copulation and parturition can reach 10–12 months.[10] Delayed implantation is a trait that distinguishes the species from the European otter, which lacks this feature.[27] Young are born between February and April,[1] and parturition lasts 3–8 hours.[10]

In early spring, expectant mothers begin to look for a den where they can give birth to the yearlings they will soon have. The female otters do not dig their own dens; instead, they rely on other animals, like beavers, to provide suitable environments to raise their offspring. When the mothers have established their domain, they give birth to several kits.[12] Litter size can reach five, but usually ranges from one to three.[10] Each otter pup weighs approximately five ounces.[12] At birth, the river otters are fully furred, blind, and toothless. The claws are well-formed and facial vibrissae (about 5 mm long) are present. The kits open their eyes after 30–38 days. The newborns start playing at 5–6 weeks and begin consuming solid food at 9–10 weeks. Weaning occurs at 12 weeks, and females provide solid food for their progeny until 37–38 weeks have transpired. The maximum weight and length of both sexes are attained at 3–4 years of age.[10]

The mothers raise their young without aid from adult males. When the pups are about two months old, their mother introduces them to the water. Otters are natural swimmers and, with parental supervision, they acquire the skills necessary to swim.[12] The otters may leave the den by eight weeks and are capable of sustaining themselves upon the arrival of fall, but they usually stay with their families, which sometimes include the father, until the following spring. Prior to the arrival of the next litter, the otter yearlings venture out in search of their own home ranges.[28]

Geographic range

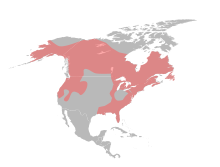

The Northern American river otter is found throughout North America, inhabiting inland waterways and coastal areas in Canada, Alaska, the Pacific Northwest, the Atlantic states, and the Gulf of Mexico. River otters also currently inhabit coastal regions throughout the United States and Canada. In the United States, the otters are present in states bordering the Great Lakes, Atlantic Ocean, and the Gulf of Mexico. North American river otters also inhabit the forested regions of the Pacific coast in North America. The species is also present throughout Alaska, including the Aleutian Islands, and the north slope of the Brooks Range. However, urbanization and pollution instigated reductions in range area.[1] Otter populations are scarce or locally extinct throughout much of the eastern, central, and southern United States.[14] The river otters are now absent or rare in Arizona, Hawaii, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, and West Virginia. Reintroduction projects have expanded the distribution of the river otters in recent years, especially in the Midwestern United States. In Canada, North American river otters occupy all provinces and territories, except for Prince Edward Island.[1]

Historical records indicate that river otters were once populous throughout most major drainages in the continental United States and Canada prior to European settlement. North America’s largest otter populations were found in areas with an abundance and diversity of aquatic habitats such as coastal marshes, the Great Lakes region, and glaciated areas of New England. In addition, riverine habitats in interior regions supported smaller, but practical, otter populations.[1] However, large river otter populations never occurred in areas of southern California, New Mexico, and Texas, as well as the Mojave desert regions of Nevada and Colorado. In Mexico, the otters lived in the deltas of the Rio Grande and Colorado rivers.[14]

Habitat

Although commonly called a "river otter", the name can be misleading, as the animals inhabit marine as well as freshwater environments. The freshwater environments include standing bodies of water, such as lakes. Some populations permanently reside in marine shoreline habitats.

The North American river otter is found in a wide variety of aquatic habitats, both freshwater and coastal marine, including lakes, rivers, inland wetlands, coastal shorelines and marshes, and estuaries. It can tolerate a great range of temperature and elevations. A river otter's main requirements are a steady food supply and easy access to a body of water. However, the North American river otter is sensitive to pollution, and will disappear from tainted areas.[14]

Like other otters, the North American river otter lives in a holt, or den. The den is constructed in the burrows of other animals, or in natural hollows, such as under a log or in river banks. An entrance, which may be under water or above ground, leads to a nest chamber lined with leaves, grass, moss, bark, and hair.[14] Den sites include burrows dug by Woodchucks (Marmota monax), Red Foxes (Vulpes vulpes), Nutrias (Myocastor coypus), Beavers, or beaver and Muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus) lodges. River otters also may use hollow trees or logs, undercut banks, rock formations, backwater sloughs, and flood debris. The usage of den and resting sites is chiefly opportunistic, although locations that provide protection and seclusion are preferred.[10]

Population localization

Aquatic life ties North American river otters almost exclusively to permanent watersheds.[10] The river otters favor bog lakes with banked shores containing semi-aquatic mammal burrows and lakes with beaver lodges. The otters avoid water bodies with gradually sloping shorelines of sand or gravel. In Maine, use of watersheds by river otters is negatively associated with the proportion of mixed hardwood-softwood stands in forested areas adjacent to waterways. However, it is positively associated with the number of beaver flowages, watershed length, and average shoreline diversity. In Idaho, river otters prefer valley habitats over mountainous terrain, and they select valley streams over valley lakes, reservoirs, and ponds. Log jams are heavily used by river otters when present. In Florida, inhabitation of North American river otters is lowest in freshwater marshes, intermediate in salt marshes, and highest in swamp forests. During the dry season, river otters will recede from the marshland and move to permanent ponds where water is available and food is in greater supply. In Idaho and Massachusetts, ecological elements preferred for latrine sites include large conifers, points of land, beaver bank dens and lodges, isthmuses, mouths of permanent streams, or any object that protrudes from the water.[1]

River otters often reside in beaver ponds, but encounters between otters and beavers may not be hostile. In Idaho, otters and beavers were recorded in the same beaver lodge simultaneously on three separate occasions. The otters may compete with the American Mink (Mustela vison) for resources. In Alaska, the two species living in marine environments indicate niche separation through resource partitioning probably related to the swimming abilities of these mustelids.[10]

Fish

River otters consume an extensive assortment of fish species ranging in size from 2 to 50 centimeters (0.8 to 19.5 inches) that impart sufficient caloric intake from a minute amount of energy expenditure.[19] River otters generally feed on prey that is in larger supply and easier to catch. As a result, slow swimming fishes are consumed more often than game fishes when both are equally available.[21][25] Slow-moving species include Suckers (Catostomidae); Sunfishes and Bass (Centrarchidae); and Daces, Carp, and Shiners (Cyprinidae).[18] For instance, Catostomidae are the primary dietary component of river otters in Colorado's Upper Colorado River Basin.[29] Likewise, the Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio) is a preferred fish species for the otter in other regions of Colorado.[29] Fish species that have frequently been found in the diet of the North American river otter include: Catostomidae, which consists of Suckers (Catostomus spp.) and Redhorses (Moxostoma spp.); Cyprinidae, made up of Carp (Cyprinus spp.), Chubs (Semotilus spp.), Daces (Rhinichthys spp.), Shiners (Notropis and Richardsonius spp.), and Squawfishes (Ptychocheilus spp.); and Ictaluridae, which consists of Bullheads and Catfish (Ictalurus spp.).[15] Other fishes that are an integral part of the river otter's diet are those that are often plentiful and found in large schools: Sunfishes (Lepomis spp.); Darters (Etheostoma spp.); and Perches (Perca spp.).[21][22][15] Bottom dwelling species, which have the tendency to remain immobile until a predator is very close, are susceptible to river otters. These include Mudminnows (Umbra limi) and Sculpins (Cottus spp.).[21][22][15] Game fishes, such as Trout (Salmonidae) and Pike (Esocidae), are not a significant component of the river otter's diet.[21][19] They are less likely to be prey for the North American river otter since they are fast-swimming and can find good escape cover.[19] However, river otters will prey on Trout, Pike, Walleye (Sander vitreus vitreus), Salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.), and other game fishes during spawning.[22]

Adult river otters are capable of consuming 1 to 1.5 kilograms (2 to 3 pounds) of fishes per day.[25] A study conducted on captive otters revealed that they preferred larger fishes ranging from 15 to 17 centimeters (6 to 7 inches) more than smaller fishes ranging from 3 to 4 inches (8–10 centimeters) and the otters had difficulty catching fish species less than 10 centimeters (4 inches) or larger than 17 centimeters (7 inches).[17] Otters are known to take larger fishes on land to eat, whereas smaller fishes are consumed in the water.[25]

Crustaceans

Otters may prefer to feed on crustaceans, especially crayfish (Cambarus, Pacifasticus, and others) more than fish where they are locally and seasonally plentiful.[18] In Georgia, crayfish accounted for two-thirds of the prey in the summer diet and their remnants were present in 98% of the summer spraint. In the winter, crayfish made up one-third of the otter's diet.[30] A study conducted on North American river otters in a southwestern Arkansas swamp identified a correlation between crayfish consumption, fish consumption, and water levels.[31]

During the winter and spring, when the water levels were higher, otters had a greater tendency to prey upon crayfish (73% of scats had crayfish remains) rather than fish.[31] However, when water levels are lower, crayfish will seek out shelter while fish become more highly concentrated and susceptible to predation. Therefore, fish are more vulnerable to being preyed upon by otters because the crayfish have become more difficult to obtain.[18]

Reptiles and amphibians

Amphibians, where regionally accessible, have been found in the river otter's diet during the spring and summer months, as indicated in many of the food habit studies.[21][23] The most common amphibians recognized were frogs (Rana and Hyla).[22] Specific species of reptiles and amphibians preyed upon by river otters include: Boreal Chorus Frogs (Pseudacris maculata); Canadian Toads (Bufo hemiophrys); Wood Frogs (Rana sylvatica);[23] Bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana); Green Frogs (Rana clamitans);[25] Northwestern Salamander (Ambystoma gracile); Pacific Giant Salamander (Dicamptodon ensatus); Rough-skinned Newt (Taricha granulosa);[22] and Garter Snakes (Thamnophis).[22][15]

Amphibians and reptiles are more obtainable by the river otter during the spring and summer as a result of breeding activity, appropriate temperatures, and water supply for the prey.[31]

Birds

Waterfowl, rails, and some colonial nesting birds are preyed upon by otters in various areas.[21][29] Susceptibility of these species to the river otter is greatest during the summer (when waterfowl broods are vulnerable) and autumn.[21] The otters have also been known to catch and consume moulting American Wigeon (Mareca americana) and Green-winged Teal (Anas crecca).[23] Other species of birds found within the river otter's diet include: Northern Pintail (Anas acuta); Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos); Canvasback (Aythya valisineria); Ruddy Duck (Oxyura jamaicensis); and the American Coot (Fulica americana).[22]

Despite the consumption of birds by river otters, they do not feed on bird eggs.[17]

Insects

Aquatic invertebrates have been recognized as an integral part of the river otter's diet.[23][15][25][29] Otters consume more aquatic insects in the summer as the invertebrate populations increase and specific life stages heighten their susceptibility.[23] Most aquatic invertebrates preyed upon by the river otter are from the families Odonata (dragonfly nymphs), Plecoptera (stonefly nymphs), and Coleoptera (adult beetles).[23][29] Invertebrates discovered within scats or digestive tracts could most likely be a secondary food item, first being consumed by the fish that are subsequently preyed upon by the otters.[20][22]

Mammals

Mammals are rarely consumed by river otters and are not a major dietary staple.[20][19] Mammals that are preyed upon by otters are characteristically small or are a type species found in riparian zones.[29] The few occurrences of mammals found in the river otter's diet include: Muskrats (Ondatra zibethicus); Meadow Voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus); Eastern Cottontails (Sylvilagus floridanus); and Snowshoe Hares (Lepus americanus).[23][25] [32]

There are varying records of otters preying upon beavers (Castor canadensis). Otter predation on beavers has been reported in the southern boreal forest of Manitoba.[33] Trappers in Alberta, Canada commonly assert that otters are major predators of beavers.[23] A 1994 river otter study reported findings of beaver remains in 27 out of 1,191 scats analyzed.[23] However, many other studies did not report any findings of beaver remains in the scat sampled.[31][34]

Human Interaction

In rare occasions, the North American River Otter has been known to bite humans. The first recorded bite of a human happened to Hannah Berlin-Berns on August 17, 1998 on Big Deep Lake in Hackensack, Minnesota.

Threats

The otter has few natural predators when in water. Aquatic predators include the Alligator (Alligator mississippiensis), American Crocodile (Crocodylus acutus), and Killer Whale (Orcinus orca).[10] On land or ice, the river otter is considerably more vulnerable. Terrestrial predators include: the Bobcat (Lynx rufus), Mountain Lion (Felis concolor), Coyote (Canis latrans), Domestic Dog (Canis lupus familiaris), Gray Wolf (Canis lupus), Red Fox, and Black Bear (Ursus americanus).[26] Most river otter mortality is caused by human-related factors such as trapping, illegal shooting, roadkills, and accidental captures in fish nets or set lines. Accidental deaths of river otters may be the result of ice flows or shifting rocks. Starvation may occur due to excessive tooth damage.[10]

Threats to otter populations in North America vary regionally. Otter inhabitation is affected by type, distribution, and density of aquatic habitats and characteristics of human activities. Preceding the settlement of North America by Europeans, otters were prevalent among aquatic habitats throughout most of the continent. Trapping, loss or degradation of aquatic habitats through filling of wetlands, and development of coal, oil, gas, tanning, timber, and other industries, resulted in extirpations, or declines, in otter populations in many areas. In 1980, an examination conducted on U.S. river otter populations determined that they were extirpated in 11 states and had experienced drastic lapses in 9 other states. The most severe population declines occurred in interior regions where fewer aquatic habitats supported fewer otter populations. Although the distribution of otters became reduced in some regions of southern Canada, the only province-wide extirpation occurred on Prince Edward Island.[1]

During the 1970s, improvements in natural resource management techniques emerged, along with increased concerns about otter population declines in North America. Consequently, many wildlife management agencies developed strategies to restore or enhance otter populations, including the use of reintroduction projects. Since 1976, over 4,000 otters have been reintroduced in 21 U.S. states. All Canadian provinces except Prince Edward Island and 29 U.S. states have viable populations that sustain annual harvests. Annual harvest numbers of Northern river otters are similar for Canada and the United States, with most pelts being used in the garment industry. In the late 1970s, annual harvest in North America reached approximately 50,000 pelts, for a value of U.S. $3 million. Otters are inadvertently harvested by traps set for beavers, and therefore management plans should consider both species simultaneously. While current harvest strategies do not pose a threat to maintaining otter populations, harvest may limit expansion of otter populations in some areas.[1] Otter harvests correlate positively with the beaver harvests and with the average beaver pelt price from the preceding year. Fur of the river otter is thick and lustrous and is the most durable of native American furs. River otter pelts are used as the standard for rating the quality of other pelts.[10]

Oil spills present a localized threat to otter populations, especially in coastal areas. Water pollution and other diminution of aquatic and wetland habitats may limit distribution of otters and pose long-term threats if the enforcement of water quality standards is not upheld. Acid drainage from coal mines is a persistent water quality issue in some areas, as it eliminates otter prey. This dilemma prevents, and consequently inhibits, recolonization or growth of otter populations. Recently, there has been discussion of long-term genetic consequences of reintroduction projects on remnant otter populations. Similarly, many perceived threats to otters such as pollution and habitat alterations have not been rigorously evaluated. Little study has gone into assessing the threat of disease to wild river otter populations. As a result, it is poorly understood and documented. River otters may be victims of canine distemper, rabies, respiratory tract disease, and urinary infection. In addition, North American river otters can contract jaundice, hepatitis, feline panleucopenia, and pneumonia. River otters host numerous endoparasites such as nematodes, cestodes, trematodes, the sporozoan Isopora, and acanthocephalans. Ectoparasites include ticks, sucking lice Latagophthirus rauschi, and the flea Oropsylla arctomys.[1]

Conservation status

Lontra canadensis is listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). River otters have been virtually eliminated through many parts of their range, especially around heavily populated areas in the midwestern and eastern United States.[35]Appendix II lists species that are not necessarily threatened with extinction currently, but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled.[36]

The North American river otter is identified as a species of Least Concern according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Redlist. This species is considered to be Least Concern as it is not currently declining at a rate sufficient for a threat category. By the early 1900s, river otter populations had declined throughout large portions of their historic range in North America. However, improvements in water quality (through enactment of clean water regulations) and furbearer management techniques have permitted river otters to regain portions of their range in many areas. Reintroduction projects have been particularly valuable in restoring river otter populations in many areas of the United States. However, river otters remain rare or absent in the southwestern United States. Water quality and development inhibit recovery of populations in some areas. The species is widely distributed throughout its range. In many places, the populations have re-established themselves because of conservation initiatives. There is an ongoing discussion about the problem of reintroduction of river otters. In recent years, it is feared that it may contaminate the genetic structure of the native population.[1]

The major threat to conservation of the river otter is habitat degradation and pollution. River otters are highly sensitive to pollution and readily accumulate high levels of mercury, organochlorine compounds, and other chemical elements. The species is often used as a bioindicator because of their position at the top of the food chain in aquatic ecosystems. Environmental disasters, such as oil spills, may increase levels of blood haptoglobin and interleukin-6 immunoreactive protein, but decrease body mass. Home ranges of river otters increase in size on oiled areas compared to non-oiled areas, and individual otters also modify their habitat use. Declines in the richness and diversity of prey species may explain these changes.[10]

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Serfass, T. (2008). "Lontra canadensis". 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2008. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "North American Mammals: Lontra canadensis (Lutra canadensis)". National Museum of Natural History. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- ^ a b Feldhamer, George A. (2003). Wild Mammals of North America: Biology, Management, and Conservation. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 348–733. ISBN 0801874165.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "River Otter, Lutra canadensis". Canada's Aquatic Environments. University of Guelph. 2002. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Mammals". University of British Columbia: Cowan Vertebrate Museum. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ^ Rice, D.W. (1998). Marine Mammals of the World: Systematics and Distribution. Lawrence, Kansas: Allen Press. p. 231.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Koepfli, Klaus-Peter (2008). "Multigene phylogeny of the Mustelidae: Resolving relationships, tempo and biogeographic history of a mammalian adaptive radiation". BMC Biology. 6 (1): 10. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-6-10. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Koepfli, K.P. (1998). "Phylogenetic relationships of otters (Carnivora: Mustelidae) based on mitochondrial cytochrome b sequences". Journal of Zoology. 246 (4): 401–416. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1998.tb00172.x.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Otter". National Park Service. 2006-07-26. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Lariviere, Serge (1998-06-01). "Lontra canadensis" (PDF). Mammalian Species (587): 1–8. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lariviere, Serge (2002-12-26). "Lutra maculicollis" (PDF). Mammalian Species (712): 1–6. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e "North American River Otter". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2008-12-24.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Cite error: The named reference "NGS" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ American Natural History, by John Davidson Godman, published by Hogan & Thompson, 1836

- ^ a b c d e f g Dewey, Tanya (2003). "Lontra canadensis". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h Melquist, W.E. (1983). "Ecology of river otters in west central Idaho". Wildlife Monographs. 83: 1–60.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Grudger, E.W. (1927). "Fishing with the otter". The American Naturalist. 61 (674): 193–225. doi:10.1086/280146.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d Erlinge, Sam (1968). "Food studies on captive otters Lutra lutra L". Oikos. 19 (2): 259–270. doi:10.2307/3565013.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Cite error: The named reference "Erlinge" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c d Route, W.T. (1988). "Distribution and abundance of river otter in Voyageurs National Park, Minnesota". Resource Management Report MWR-10. National Park Service.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Melquist, W.E. (1987). "River otter". Wild Furbearer Management and Conservation in North America (M. Novak, J.A. Baker, M.E. Obbard, and B. Malloch ed.). Toronto, Canada: Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. pp. 626–641.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Larsen, D.N. (1984). "Feeding habits of river otters in coastal southeastern Alaska". Journal of Wildlife Management. 48 (4): 1446–1452.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h Toweill, D.E. (1982). "The Northern River Otter Lutra canadensis (Schreber)". Wild mammals of North America (J.A. Chapman and G.A. Feldhamer ed.). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Toweill, D.E. (1974). "Winter food habits of river otters in western Oregon". Journal of Wildlife Management. 38 (1): 107–111.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Reid, D.G. (1994). "Food habits of the river otter in a boreal ecosystem". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 72 (7): 1306–1313. doi:10.1139/z94-174.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Grenfell, William E., Jr. (1974). "Food habits of the river otter in Suisun Marsh, Central California" (PDF). California State University. Retrieved 2009-01-14.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Serfass, T.L. (1990). "Feeding relationships of river otters in northeastern Pennsylvania". Transactions of the Northeast Section of the Wildlife Society (47): 43–53.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Boyle, Steve (2006). "North American River Otter (Lontra canadensis): a technical conservation assessment" (PDF). USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Retrieved 2009-01-14.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Ware, George W. (2001). Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. Springer. ISBN 0387951377.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Orr, Eric (2007). "North American River Otter". Chattooga River Conservancy. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e f Berg, Judith (1999). "Final report of the river otter research project on the Upper Colorado River Basin in and adjacent to Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado" (PDF). National Park Service: Rocky Mountain National Park, West Unit. Retrieved 2009-01-14.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Noordhuis, R. (2002). "The river otter (Lontra canadensis) in Clarke County (Georgia, USA): survey, food habits, and environmental factors". IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin. 19 (2): 75–86.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d Tumlison, R. (1987). "Seasonal changes in food habits of river otters in southwestern Arkansas beaver swamps". Mammalia. 51 (2): 225–232.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Field, R.J. (1970). "Winter habits of the river otter (Lutra Canadensis) in Michigan". Michigan Academician (3): 49–58.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Green, H.U. (1932). "Observations on the occurrence of otter in the Riding Mountain National Park, Manitoba, in relation to beaver life". Canadian Field-Naturalist. 46: 204–206.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Gilbert, F.F. (1982). "Food habits of mink (Mustela vison) and otter (Lutra canadensis) in northeastern Alberta". Canadian Journal of Zoology. Vol. 60. pp. 1282–1288.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Duplaix, Nicole. "Lutra canadensis" (PDF). Management Authority of the United Kingdom. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. Retrieved 2008-12-27.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "The CITES Appendices". Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. Retrieved 2008-12-27.

Further reading

- Hans Kruuk. (2006). Otters: ecology, behaviour and conservation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-856586-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Recent monograph on otters in general, with many references to the river otter.

External links

- Lontra canadensis from the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology's "Animal Diversity Web"

- An Otter Family Album, a pictoral chronicle of 25 years of otter observations by J. Scott Shannon

- Nature: Yellowstone Otters, educational resources from the Public Broadcasting System

- North American River Otter species profile by the Nature Conservancy

- North American River Otter fact sheet from the Woodland Park Zoo in Seattle, Washington

- Otters a comparison of river and sea otters in the marine environment by the Capital Regional District, Victoria, British Columbia

- River Otter Longevity records from the Human Ageing Genomic Resources website, a project of the University of Liverpool.

- 3D Images of the River Otter Skull from the National Science Foundation Digital Library at the University of Texas-Austin.

- Northern River Otter at Natural History Notebooks, Canadian Museum of Nature, at http://nature.ca.