Themes in Avatar

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| James Cameron on themes in Avatar | |

The 2009 action-adventure film Avatar has earned widespread success, becoming the highest-grossing film of all time.[1] The blockbuster has provoked vigorous discussion of a wide variety of cultural, social, political, and religious themes identified by critics and commentators, to which the film's writer and director James Cameron responded that he hoped to create an emotional reaction and make the public conversation gravitate towards socio-political, cultural, environmental, and spiritual topics.[2] The broad range of Avatar's intentional or perceived themes has prompted reviewers to call it "an all-purpose allegory"[3] and "the season's ideological Rorschach blot".[4] One reporter even suggested that the politically-charged punditry has been "misplaced": reviewers should have seized on the opportunity to take "a break from their usual fodder of public policy and foreign relations" rather than making an ideological battlefield of this "popcorn epic".[5]

Dominant motifs in the discussion of the film's themes include environmentalism, imperialism and racism, militarism and patriotism, corporate greed, citizens' property rights, a conflict between technology and nature, a clash of civilizations, and spirituality versus religion.[6][7] Cameron has specifically mentioned deliberate connections between the film's plot and the religious concepts and iconography of Hinduism.[8][9]

Political themes

Director James Cameron called Avatar "very much a political film" and added, "as an artist, I felt a need to say something about what I saw around me.... This movie reflects that we are living through war. There are boots on the ground, troops who I personally believe were sent there under false pretenses, so I hope this will be part of opening our eyes."[10]

Imperialism and colonialism

Avatar describes the battle by an indigenous people, the Na'vi, against alien human imperialist oppression. The film presents the struggle of these native people as symbolic of similar conflicts throughout human history. James Cameron acknowledged that the film is "certainly...about imperialism in the sense that the way human history has always worked is that people with more military or technological might tend to supplant or destroy people who are weaker, usually for their resources"[6] and said that references to the colonial period are in the film by design."[11]

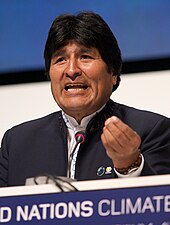

Adam Cohen of The New York Times called the film's anti-imperialist message "a 22nd-century version of the American colonists vs. the British, India vs. the Raj, or Latin America vs. United Fruit".[12] Evo Morales, the first indigenous president of Bolivia, praised Avatar for its "profound show of resistance to capitalism and the struggle for the defense of nature".[13] Similarly, Dennis Atkins of The Courier Mail saw the film as "a clear message about dominant, aggressive cultures subjugating a native population in a quest for resources or riches."[14] George Monbiot of Guardian explained conservative criticism of Avatar by what he called the film's "chilling metaphor" of the European and American genocide against the native residents of the Americas.[15]Saritha Prabhu, an Indian-born columnist for The Tennessean, wrote about the parallels between the plot and how "Western power colonizes and invades the indigenous people (native Americans, Eastern countries, you substitute the names), sees the natives as primitives/savages/uncivilized, is unable or unwilling to see the merits in a civilization that has been around longer, loots the weaker power, all while thinking it is doing a favor to the poor natives."[16] Huascar Vega Ledo in BolPress saw the human colonizers on Pandora as having "the imperial attitude...similar to that of NATO in Iraq or Israel in Palestine." [17]

Dalia Salaheldin of IslamOnline found it reassuring that "When the Na'vi clans are united, and a sincere prayer is offered, the bows and arrows equipped 'primitive savages' win the war".[18] In the same spirit, Palestinian activists painted themselves blue and dressed like the Na'vi during their weekly protest in the village of Bilin against Israel's separation barrier, equating their struggle with the one portrayed in the film.[19][20] However, Seraj Assi argued in Arab News that "for Palestinians, 'Avatar' is rather a reaffirmation and confirmation of the claims about their incapability to lead themselves and build their own future."[21]

Other critics objected to what they saw as a misrepresentation of capitalism in the film. Forbes' columnist Reihan Salam said that while making capitalism is the villain of Avatar, Cameron fails to understand is that capitalism represents a far more noble and heroic way of life than that led by the Na'vi because it "give[s] everyone an opportunity to learn, discover, and explore, and to change the world around us."[22] David Brooks in The New York Times criticized what he saw as the White Messiah complex in the film, whereby the Na'vi "can either have their history shaped by cruel imperialists or benevolent ones, but either way, they are going to be supporting actors in our journey to self-admiration."[23] Others disagree: "That seems a bit much. First off, [Jake is] handicapped. Second off, he ultimately becomes one of [the Navi] and wins their way."[24]

War and militarism

Anti-militarism is viewed as another deliberate theme of the film. Cameron acknowledged that Avatar contains implicit criticism of America's involvement in the War in Iraq and that Americans had a "moral responsibility" to understand the impact of their country's recent military campaigns.[25] Commenting on the term "shock and awe" in the film, Cameron said: "We know what it feels like to launch the missiles. We don't know what it feels like for them to land on our home soil, not in America."[25] He added that "we're in a century right now in which we're going to start fighting more and more over less and less"[6] and revealed that "the Iraq stuff and the Vietnam stuff is there by design."[11]

Christian Hamaker of Crosswalk.com noted that, "in describing the military assault on Pandora, Cameron cribs terminology from the ongoing war on terrorism and puts it in the mouths of the film's villains, who proclaim a "shock and awe campaign" of "pre-emptive action," as they "fight terror with terror. Cameron's sympathies, and the movie's, clearly are with the Na'vi — and against the military and corporate men."[26] Armond White of New York Press dismissed the film's perceived anti-militaristic subtext as "essentially a sentimental cartoon with a pacifist, naturalist message" that uses villainous Americans to misrepresent the facts of militarism, capitalism, and imperialism.[27] Answering comments on the film as insulting to the US military, bloggger Mike Boehm in Los Angeles Times said that "if any U.S. forces that ever existed were being insulted, it was the ones who fought under George Armstrong Custer, not David Petraeus or Stanley McChrystal."[5]

Conversely, Pierre Desjardins of Le Monde opined that, contrary to the perceived pacifism of Avatar, it justifies war and violence, especially in response to an attack, by way of attributing militaristic roles and symbols to the film's positive characters and remarked that "all wars, even those that seem the most insane, always occur for the 'right reasons'."[28] Ann Marlowe called it "in an insider's way" both pro- and anti-military, and saw it as "a metaphor for the networked military."[29]

Anti-patriotism

Some conservative critics commented on what they perceived as Avatar's anti-American message, equating RDA's private security force to American soldiers. Russell D. Moore in The Christian Post stated that, "If you can get a theater full of people in Kentucky to stand and applaud the defeat of their country in war, then you've got some amazing special effects" and criticized Cameron for what he saw as an unnuanced depiction of the American military as "pure evil" in the film.[30] John Podhoretz of The Weekly Standard argued that the film asks the audience to "root for the defeat of American soldiers" and called it "a deep expression of anti-Americanism ... with its hatred of the military and American institutions and the notion that to be human is just way uncool."[31] John Nolte's review in BigHollywood called Avatar the "liberal tell" of "a thinly disguised, heavy-handed and simplistic sci-fi fantasy/allegory critical of America from our founding straight through to the Iraq War."[32] Charles Mudede of The Stranger said that with the release of the film "the American culture industry exports an anti-American spectacle to an anti-American world."[33] Film critic Debbie Schlussel dismissed Avatar as "cinema for the hate America crowd."[34]

Answering this criticism, James Cameron said that "the film is definitely not anti-American"[35] and that "part of being an American is having the freedom to have dissenting ideas."[10] Ann Marlowe of Forbes concurred, calling the film "the most neo-con movie ever made" for its "deeply conservative, pro-American message."[29] Eric Ditzian of MVT reckoned that "it'd take a great leap of logic to tag 'Avatar' as anti-American or anti-capitalist."[36] But Cameron also acknowledged that one can interpret the film in many different ways: "The bad guys could be America in this movie, or the good guys could be America in this movie, depending on your perspective."[6]

September 11 attacks

Although reportedly not a deliberate theme of the film,[25] reviewers perceived visual and conceptual similarities between the air raid on and the resultant collapse of the Na'vi habitat Home Tree in Avatar and the September 11 attack on the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center.

Ben Hoyle of The Australian observed that after the Na'vi homes collapse in flames, the scene of landscape coated in ash and floating embers is reminiscent of Ground Zero after the September 11 attacks.[25] Ann Marlowe of Forbes also saw "the wintry ash of the destroyed sacred tree" and "the image of the helicopters dwarfed by the huge tree" as mirroring the terrorist assault.[29] Sam Adams of The A.V. Club called the resonance with the images of the attack on lower Manhattan "inescapable", except that "the U.S.’ stand-ins are the perpetrators, and not the victims" and described it as "the movie’s most seditious act, only with the terms reversed."[37]

Reviewers also criticized James Cameron for a "tacky metaphor for the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center,"[32] for his "audacious willingness to question the sacred trauma of 9/11,"[37] and for what they saw in the film as Cameron's justification for the allied forces' war on terror led by an American marine riding on the "imperial American eagle."[28] Armond White of The New York Press blamed Cameron for "the hypocrisy," "contradictory thinking" and "beserk analogy" of presenting the World Trade Center as "an altar of U.S. capitalism," which the author described as "a guilt-ridden 9/11 death wish."[27]

Responding to criticism of the scene, James Cameron said he had been "surprised at how much it did look like September 11," but added that he did not think that it was necessarily a bad thing.[25]

Social and cultural themes

Avatar explores a number of social, cultural, ethical, and moral issues, profusely commented on by its reviewers. Summing them up, Adam Cohen said in his editorial for The New York Times that the film is morally educating as being "fundamentally about the moral necessity of seeing other beings fully" and called the theme "the movie’s moral touchstone."[12]

Technology vs. culture

The film also focuses on the expansive technocratic conquest by the humans as an attack on cultural and moral values. James Cameron explained that in creating the noble and cultured Na'vi living in commune with the lush naturescape he was attempting to create a race that was aspirational: "The Na'vi represent the better aspects of human nature, and the human characters in the film demonstrate the more venal aspects of human nature."[10]

David Quinn of the Irish Independent noticed that the film was contrasting its "mix of New Age environmentalism and the myth of the Noble Savage" with the corruption of the "civilized" white man.[38] Columnist Oscar van den Boogaard, writing for De Standaard in Belgium said, "It's about the brutality of man, who shamelessly takes what isn't his."[39] Angolan critic Altino Matos saw in the film a message of hope, and wrote in the Jornal De Angola, "With this union of humans and aliens comes a feeling that something better exists in the universe: the respect for life. Above all, that is what ... Avatar suggests."[40]

Analyzing the contrast between technology and culture in Avatar, Maxim Osipov wrote in the Hindustan Times and The Sydney Morning Herald:

The 'civilised humans' turn out as primitive, jaded and increasingly greedy, cynical, and brutal – traits only amplified by their machinery – while the ‘monkey aliens’ emerge as noble, kind, wise, sensitive and humane. We, along with the Avatar hero, are now faced with an uncomfortable yet irresistible choice between the two races and the two worldviews. And invariably, along with him we cannot help but lean toward the far more civilised insides within the long-tailed, blue-skinned, and technologically infantile exterior.

Osipov also commended Cameron for “convincingly” defining culture and civilization as “the qualities of kindness, gratitude, regard for the elder, self-sacrifice, respect for all life and ultimately humble dependence on a higher intelligence behind nature.”[41][42] Conversely, David Brooks of The New York Times opined that Avatar creates "a sort of two-edged cultural imperialism" as an offensive cultural stereotype that white people are rationalist and technocratic while colonial victims are spiritual and athletic and that illiteracy is the path to grace.[23]

Climate advocate Joseph Romm wrote, "Interestingly, the movie is mostly pro-science while still being anti-technology."[24]

Environmentalism

James Cameron said he envisioned Avatar as a broader metaphor of how we treat the natural world.[7] In an interview with Terry Gross of National Public Radio he explained that, "at a very generalized level, Avatar is saying our attitude about indigenous people and our entitlement about what is rightfully theirs is the same sense of entitlement that lets us bulldoze a forest and not blink an eye.... And we can't just go on in this unsustainable way, just taking what we want and not giving back".[11] On the Charlie Rose talk show, Cameron said that he had deliberately kept the environmental and spiritual themes in the film despite requests to "down-peddle" them, because "we are going to go through a lot of pain and heartache if we don't acknowledge our stewardship responsibilities to nature."[2] He has also expressed encouraged everyone be a tree hugger[10] and urged that we "make a fairly rapid transition to alternate energy."[43]

Avatar has been called "without a doubt the most epic piece of environmental advocacy ever captured on celluloid.... The film hits all the important environmental talking-points – virgin rain forests threatened by wanton exploitation, indigenous peoples who have much to teach the developed world, a planet which functions as a collective, interconnected Gaia-istic organism, and evil corporate interests that are trying to destroy it all."[44] Lori Pottinger of Huffington Post connected the film to the endangerment of biodiversity in the Amazon rainforests of Brazil by dam construction, logging, mining, and clearing for agriculture.[45] Melinda Liu in Newsweek saw the destruction of Home Tree in Avatar as yet another environmental subtext in the film hinting at rampant tree-felling in Tibet.[46] Similarly, in a case of life seeking to imitate art, the 8,000-strong Dongria Kondh tribe from Orissa, eastern India, appealed to James Cameron to help them stop a mining company from opening a bauxite open-cast mine on their sacred Niyamgiri mountain, reckoning that the author of Avatar would understand their plight. An advertisement in Variety magazine said: "Appeal to James Cameron. Avatar is fantasy ... and real. The Dongria Kondh tribe in India are struggling to defend their land against a mining company hell-bent on destroying their sacred mountain. Please help the Dongria."[47][48] In a similar bid for environmental protection, a coalition of over fifty environmental and aboriginal organizations of Canada ran a full-page ad in the special Oscar edition of Variety comparing their fight against Canada's Alberta oilsands to the Na'vi insurgence in Avatar — an analogy disputed by the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers.[49][50] Authors also compared the film's depiction of destructive corporate mining for unobtanium in the Na'vi habitat with the mining and milling of uranium near the Navajo reservation in New Mexico.[51] Cameron acknowledged some of these environmental issues in his interview with Time magazine.[43] He was also awarded the inaugural Temecula Environment Award for Outstanding Social Responsibility in Media by three environmentalist groups for portrayal of environmentalist struggles that they saw to be similar to their own.[52]

However, Armond White of New York Press dismissed Avatar's alleged pro-environmental stance as inconsistent: "While prattling about man’s threat to environmental harmony, Cameron’s really into the powie-zowie factor: destructive combat and the deployment of technological force. Avatar condemns mankind’s plundering and ruin of a metaphorical planet’s ecology and the aboriginals’ way of life. Cameron fashionably denounces the same economic and military system that make his technological extravaganza possible. It’s like condemning NASA — yet joyriding on the Mars Exploration Rover."[27]

State vs. citizens' rights

Avatar has evoked parallels with the oppressive policies of some states towards their citizens. David Boaz of the Libertarian Cato Institute said in Los Angeles Times that the film's essential conflict is a battle over property rights, "the foundation of the free market and indeed of civilization."[55]

Melinda Liu wrote for Newsweek that the destruction of the Na'vi habitat—a giant tree—is reminiscent of the forced eviction policies perpetrated by Chinese authorities, where 30 million citizens have been evicted in the course of the country's three-decade long development boom[46]—a factor some believed to have contributed to the film being pulled from Chinese 2D theaters.[56] She quoted a Chinese blogger who wrote, "China's demolition crews must go sue Cameron for copyright infringement."[46] An article in the Global Times, published by the Communist-Party's official newspaper People's Daily, called the film's plot "the spitting image of the violent demolition in our everyday life. ... [F]acing the violent demolition conducted by chengguan but instigated by real estate developers, some ordinary people have wept or burned themselves desperately, while most continue to bear unfairness in silence."[53] Similarly, Lori Pottinger linked forced eviction of the Na'vi to the displacement of tribes in the Amazon basin.[45] Yekaterina Blinova of the Russian Vedomosti newspaper used the same comparison to describe the forcible demolition of private houses in a Moscow suburb.[54]

James Cameron acknowledged analogy with some of these issues in an interview with Time magazine.[43]

Race and racism

While Cameron denied that the film is racist, telling Associated Press that the real theme of Avatar is about respecting others' differences, some reviewers saw the film as "a fantasy about race told from the point of view of white people", which reinforces "the white Messiah fable", in which the white hero saves the helpless primitive natives,[57] who are thus reduced to servicing his ambitions and proving his heroism.[21] Philosopher and critical theorist Slavoj Žižek noted that the film features "brutal racist undertones" which he identifies in, among other things, the fact that the "film enables us to practise a typical ideological division: sympathising with the idealised aborigines while rejecting their actual struggle."[58] Annalee Newitz of io9 saw Avatar as a metaphor for how European settlers in America oppressed the Indians and how "white guilt" expresses itself in continued attempts to lead people of color, albeit in a kinder way.[59] Another author ironically remarked that "in 'Avatar' there is no place for heroes of color. Yet, there is no reason to worry, since the brave-hearted white man will fix the destruction of all the 'Pandoras', such as the Caribbean and Middle East. He will never feel guilty, even when he is directly responsible for the destruction."[21]

Josef Joffe, publisher-editor of Die Zeit in Germany, said the film bows to the notion of the "noble savage" which European philosophers, including Rousseau, have written about for centuries: "So, as deep and precious as the metal in this film, slumbers a condescending, yes, even racist message. Cameron bows to the noble savages. However, he reduces them to dependents."[60] while Mark Mardell of BBC was reminded of its variant, the "magical negro" term coined by black critics who noted white authors often featured non-white characters possessed of a certain sort of natural wisdom, mystic powers, who play sidekick to the white hero and often sacrifice themselves for the central character.[61] Critics also called the Navi neural plug-n-play control over their animals "biped-centrism [which] is just another form of imperialist racism"[31] and "a sexualized conquest [that] suggests latent fascism."[27] Noting that "ultimately in Cameron's film, the only good humans are dead — or rather, resurrected as 'good Navi'," Harold Brackman in The Jerusalem Post saw this as Avatar's inadvertent promotion of neo-Nazism, or supremacy of one race over another.[62]

In Charlie Rose talk show Cameron acknowledged parallels with the "noble savage" as a reason for the film's success, but rejected claims about the film as racist:

When indigenous populations who are at a bow and arrow level are met with technological superior forces, [the indigenous] lose. If somebody doesn't help them, they lose. So we are not talking about a racial group within an existing population fighting for their rights.

emphasizing that the "noble savage" would not have won alone.[2]

The traditional Na'vi greeting "I see you" prompted Adam Cohen of The New York Times to contrast it with the principle of totalitarianism and genocide as the oppression of those who we fail to accept for what they are, quoting the Nazi ghettos for Jews and the Soviet gulags as examples.[12]

Armond White of New York Press criticized Avatar’s as "the easiest, dumbest escapism imaginable" for involving "blue cartoon creatures rather than brown, black, red, yellow real-world people."[27] Other reviews called Avatar an offensive assumption that nonwhites need the White Messiah to lead their crusades,[23] and "a self-loathing racist screed" due to the fact that all the "human" roles in the film are played by white actors and all the Na'vi characters—by African-American or Native American actors (C. C. H. Pounder, Zoe Saldana, Wes Studi, and Laz Alonso) and that the Na'vi society was strongly reminiscent of African and Indian tribal cultures.[61][63]

Human dream and guilt

| External audio | |

|---|---|

| James Cameron: Pushing the limits of imagination | |

In an interview on National Public Radio with Terry Gross, James Cameron highlighted the human dimension of Avatar, expressing surprise that "with all the talk about this movie, nobody has mentioned that the main character is disabled." Cameron explained:

Avatar comes from a childhood sense of wonder about nature... We go from this state as children where we don't know what we can't do. You fly in your dreams as a child, but you tend not to fly in your dreams as an adult. In the Avatar state, [Jake] is getting to return to that childlike dream state of doing amazing things ... In a funny way, it's actually kind of a comment on the way we find expression for our imagination [and] on the huge gap or shortfall between what you can imagine and what you can actually do.[11]

and said elsewhere that the positive public response to the Na'vi and their philosophy of connectedness to the earth and to each other means that "we have that within ourselves."[2][10]

Other reviews saw Avatar as "the bubbling up of our military subconscious ... the wish to be free of all the paperwork and risk aversion of the modern Army--much more fun to fly, unarmored, on a winged beast."[29]

Cameron also said that Avatar is a satire on the sense of human entitlement that "if we can take it, we will. And sometimes we do it in a very naked and imperialistic way, and other times we do it in a very sophisticated way with lots of rationalization — but it's basically the same thing."[11]

Similarly, a prominent Russian columnist Valery Panyushkin in Vedomosti traced Avatar popularity to its giving the audience a chance to make a correct moral choice between good and evil and, by emotionally siding with Jake's treason, to relieve "us the scoundrels" of our collective guilt for the cruel and unjust world that we have created.[64][65]

However, Armond White of New York Press criticized Avatar as "the corniest movie ever made about the white man’s need to lose his identity and assuage racial, political, sexual and historical guilt."[27] Reihan Salam in Forbes saw it as ironic that "Cameron has made a dazzling, gorgeous indictment of the kind of society that produces James Camerons."[22]

Religion and spirituality

According to James Cameron, one of the film's philosophical underpinnings is that "the N'avi represent that sort of aspirational part of ourselves that wants to be better, that wants to respect nature, while the humans in the film represent the more venal versions of ourselves, the banality of evil that comes with corporate decisions that are made out of remove of the consequences."[10][35] Film director John Boorman quoted a similar distinction as one of the key factors contributing to its success: "Perhaps the key is the marine in the wheelchair. He is disabled, but Mr Cameron and technology can transport him into the body of a beautiful, athletic, sexual, being. After all, we are all disabled in one way or another; inadequate, old, broken, earthbound. Pandora is a kind of heaven where we can be resurrected and connected instead of disconnected and alone."[38]

David Quinn of the Irish Independent agreed that spirituality "goes some way towards explaining the film's gigantic popularity, and that is the fact that Avatar is essentially a religious film, even if Cameron might not have intended it as such."[38] At the same time, Jonah Goldberg of National Review Online objected to what he saw in the film reviews as "the norm to speak glowingly of spirituality but derisively of traditional religion."[66]

Religious and mythological motifs

Other reviewers suggested that the film draws upon many existing religious and mythological motifs. S. Brent Plate of Religion Dispatches said that Avatar "begs, borrows, and steals from a variety of longstanding human stories, puts them through the grinder, and comes up with something new."[67] Vern Barnet of the Charlotte Observer opined too that Avatar borrows concepts from many religions and poses a great question of faith. He said: "The movie's Tree of Souls recalls the Norse story of the tree Yggdrasil, an example of a tree supporting the cosmos found in many traditions. Its destruction signals the collapse of the universe. Scholars call such trees the axis mundi, the center of the world."[68] Malinda Liu in Newsweek commented on the Na'vi respect of all life beings and their faith in reincarnation as being very similar to the Tibetan religious beliefs and practices,[46] while Reihan Salam of Forbes called them "perhaps the most sanctimonious humanoids ever portrayed on film."[22] Huascar Vega Ledo of the Bolivian publication BolPress explained the concept of "avatar" to signify "something born without human intervention, without intercourse, without sin," compared it to the birth of Jesus Christ, Krishna, Manco Capac, and Mama Ocllo and drew parallels between the deity Eywa of Pandora and the goddess Pachamama worshiped by the indigenous people of the Andes.[17]

On a critical note, columnist Angela Himsel in Huffington Post called Avatar "a new version of the Garden of Eden syndrome" and pointed out phonetic and conceptual similarities of the film's terminology with that of the Book of Genesis.[69]

Pantheism vs. Christianity

Some Christian reviewers saw Avatar as promoting pantheism and nature worship. Gaetano Vallini, a cultural critic for L’Osservatore Romano of the Holy See, wrote that the film "shows a spiritualism linked to the worship of nature, a fashionable pantheism in which creator and creation are mixed up."[7] Vatican Radio said that the film "cleverly winks at all those pseudo-doctrines that turn ecology into the religion of the millennium. Nature is no longer a creation to defend, but a divinity to worship."[70] Ross Douthat, a conservative columnist of The New York Times called Avatar "the Gospel According to James" and "Cameron's long apologia for pantheism [which] has been Hollywood's religion of choice for a generation now."[71] John Podhoretz of The Weekly Standard saw in the film "its mindless worship of a nature-loving tribe and the tribe's adorable pagan rituals." [31] Christian film critic David Outten said that "the danger to moviegoers is that Avatar presents the Na'vi culture on Pandora as morally superior to life on Earth. If you love the philosophy and culture of the Na'vi too much, you will be led into evil rather than away from it."[72] Outten further added:

Cameron has done a masterful job in manipulating the emotions of his audience in Avatar. He created a world where it looks good and noble to live in a tree and hunt for your food daily with a bow and arrow.... Cameron said, "Avatar asks us to see that everything is connected, all human beings to each other, and us to the Earth." This is a clear statement of religious belief. This is pantheism. It is not Christianity.[73]

Other Christian critics said that Avatar has "an abhorrent New Age, pagan, anti-capitalist worldview that promotes goddess worship and the destruction of the human race,"[74] emphasized Avatar's thematic elements deemed objectionable by Christians,[26] and suggested that Christian viewers interpret the film as a reminder of Jesus Christ as "the True Avatar."[75][17]

Conversely, Matthew J. Milliner in The Public Discourse online publication of the Witherspoon Institute maintained that the film promotes theism rather than pantheism, because "Jake Sully does not pray to a tree, but through a tree to the deity whom he addresses personally" and, unlike in pantheism, "the film's deity does indeed—contrary to the native wisdom of the Na'vi—interfere in human affairs." Quoting C. S. Lewis' Space Trilogy, he also called the film "a depiction of Eden."[76] Ann Marlowe of Forbes agreed, saying that "though Avatar has been charged with "pantheism", its mythos is just as deeply Christian."[29] Another author suggested that the film's true message is panentheism, which "leads to a renewed reverence for the natural world—a very Christian teaching."[77]

Saritha Prabhu, an Indian-born columnist for The Tennessean, saw the film as a misportrayal of pantheism and contrasted it with her own views: "What pantheism is, at least, to me: a silent, spiritual awe when looking (as Einstein said) at the 'beauty and sublimity of the universe', and seeing the divine manifested in different aspects of nature. What pantheism isn't: a touchy-feely, kumbaya vibe as is often depicted. No wonder many Americans are turned off." Prabhu also criticized Hollywood and Western media for what she saw as their generally poor job of portraying Eastern spirituality.[16] Demetria Martinez of National Catholic Reporter disagreed with the Vatican's characterization of Avatar as pagan, urging Christian critics to see the film in the historical context of "Christianity's complicity in the conquest of the Americas."[78]

Parallels with Hinduism

Acknowledging multiple thematic connections with Hinduism, Nikhat Kazmi of The Times of India equated Avatar to a treatise on Indianism "for Indophiles and Indian philosophy enthusiasts", starting from the very word Avatar itself.[79] A Houston Chronicle article discussed a number of analogies between the film and the ancient Hindu epics Mahabharata and Ramayana, as well as their depiction of the main avatars Rama and Krishna, depicted here with blue skin, black hair, and a tilak mark on the forehead.[80]

Terminology

Answering a question from Time magazine, "What is an avatar anyway?" Cameron replied, "It's an incarnation of one of the Hindu gods taking a flesh form. In this film what that means is that the human technology in the future is capable of injecting a human's intelligence into a remotely located body, a biological body."[8]

Following the film's release, a number of reviewers focused on Cameron’s choice of the religious Sanskrit term for the film's title and its connection with the film's plot. Parvathi Nayar of The Hindu reasoned that "Cameron uses the loaded Sanskrit word of the movie's title to talk of a possible future manifestation of man. A next step in our evolution, if you like, that results from man's interaction with an emotionally superior—but technologically inferior—form of alien. Can we integrate and change, rather than conquer and destroy?"[81] Conversely, Maxim Osipov of ISKCON argued in The Sydney Morning Herald that "Avatar" is a "downright misnomer" for Cameron's film because "the movie reverses the very concept [that] the term 'avatar'—literally, in Sanskrit, 'descent'—is based on. So much for a descending 'avatar', Jake becomes a refugee among the aborigines."[42]

David Quinn of Irish Independent thought that Avatar insults traditional usage of its title since it is a human, not a god, who descends in the film.[38] However, Rishi Bhutada, Houston coordinator of the Hindu American Foundation, said that while there are certain sacred terms that would offend Hindus if used improperly, avatar is not one of them.[80] Texas-based filmmaker Ashok Rao added that 'avatar' does not always mean a representative of God on Earth, but simply one being in another form — especially in literature, moviemaking, poetry and other forms of art."[80]

Iconography

Explaining the choice of the color blue for the Na'vi, Cameron said "I just like blue. It's a good color ... plus, there's a connection to the Hindu deities, which I like conceptually."[9]

Commenting on this topic, reviewers drew more detailed parallels between the Na'vi complexion and the iconography of Hinduism. An Indian film writer and director Sudipto Chattopadhyay opined that the deliberate choice of the blue skin "instantly, magically and metaphorically relates the film's protagonist to two previous avatar’s of Vishnu, namely Rama and Krishna",[82]—an observation shared by other authors,[77][83] including Dana Goodyear of The New Yorker, who described the Na'vi as Vishnu-blue.[84] Janos Gereben of San Francisco Examiner agreed, comparing the film's scene in which the blue-skinned avatar of Jake Sully flies a predator Toruk, with a 18 century Indian painting of blue-skinned Vishnu and his consort Laksmi riding through the sky on the gigantic magical bird Garuda, and called the depiction of Vishnu "'Avatar' prequel".[85]

Philosophical concepts

Reviewers also discussed explicit or implicit similarities of the film with the philosophy of Hinduism. Vern Barnet of Irish Independent suggested that, just as Hindu gods, particularly Vishnu, become avatars to save the order of the universe, the film "suggests something is terribly wrong with a rapacious greed that leads to destroying the world of nature and other civilizations, and the movie's avatar must avert ultimate doom."[38] While questioning theological correctness of the film's title, Maxim Osipov opined that the film's philosophical message was consistent overall with the Bhagavad Gita, a key scripture of Hinduism, in terms of defining what constitutes real culture and civilization.[41][42] Sudipto Chattopadhyay suggested that Cameron is alluding to the god Vishnu who regularly manifests himself in palpable form to save mankind from the impeding doomsday.[82] Tam Hunt in Noozhawk linked the Na'vi goddess Eywa, the repository of Pandora's biosphere, to the concept of Brahman as the ground of being described in Vedanta and Upanishads and likened the Na'vi ability to connect to Eywa with the realization of Atman.[77] Authors in East Valley Tribune and Philippino The News Today commented on Avatar's exposition of the Hindu concepts of divine descent and reincarnation.[83][86]

References

- ^ "All time worldwide box office grosses". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 8, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d "James Cameron, Director". charlierose.com. February 17, 2010. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ Keating, Joshua (January 17, 2010). "Avatar: an all-purpose allegory". Foreign Policy. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- ^ Phillips, Michael (January 10, 2010). "Why is 'Avatar' a film of 'Titanic' proportions?". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Boehm, Mike (February 23, 2010). "The politics of 'Avatar:'The moral question James Cameron missed". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ a b c d Ordoña, Michael (December 14, 2009). "Eye-popping 'Avatar' pioneers new technology". San Francisco Gate. Retrieved December 14, 2009.

- ^ a b c Itzkoff, Dave (January 20, 2010). "You Saw What in 'Avatar'? Pass Those Glasses!". New York Times. Retrieved January21, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Winters Keegan, Rebecca (January 11, 2007). "Q&A with James Cameron". Time magazine. Retrieved December 26, 2009. Cite error: The named reference "Time" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Svetkey, Benjamin (January 15, 2010). "'Avatar:' 11 Burning Questions". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Lang, Brent (January 13, 2010). "James Cameron: Yes, 'Avatar' is political". thewrap.com. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Gross, Terry (February 18, 2010). "James Cameron: Pushing the limits of imagination". National Public Radio. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- ^ a b c Cohen, Adam (December 25, 2009). "Next-Generation 3-D Medium of 'Avatar' Underscores Its Message". Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^ "Evo Morales praises Avatar". ABI. Huffington Post. January 12, 2010. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ Atkins, Dennis (January 7, 2010). "Conservative criticism of Avatar is misplaced". The Courier Mail. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ Monbiot, George (January 11, 2010). "Mawkish, maybe. But Avatar is a profound, insightful, important film". Guardian. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ a b Prabhu, Saritha (January 22, 2010). "Movie storyline echoes historical record". The Tennessean. Retrieved February 07, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c "Jesus Christ and the movie Avatar". BolPress. www.worldmeets.us. January 7, 2010. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name=ignored (help) - ^ Saladeldin, Dalia (January 21, 2010). "I see you..." IslamOnline. Retrieved January 22, 2010.

- ^ "Day in pictures". Associated Press. SFGate. February 12, 2010. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ^ "Palestinians dressed as the Na'vi from the film Avatar stage a protest against Israel's separation barrier". The Daily Telegraph. February 13, 2010. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ a b c Assi, Seraj (February 17, 2010). "Watching 'Avatar' from Palestinian perspective". Arab News. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ a b c Salam, Reihan (December 21, 2009). "The case against 'Avatar'". Forbes. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- ^ a b c Brooks, David (January 7, 2010). "The Messiah complex". New York Times. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- ^ a b Romm, Joseph (March 7, 2010). "Post-Apocalypse now". ClimateProgress.org. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Hoyle, Ben (December 11, 2009). "War on Terror backdrop to James Cameron's Avatar". The Australian. News Limited. Retrieved December 24, 2009.

- ^ a b Hamaker, Christian (December 18, 2009). "Otherworldly "Avatar" Familiar in the Worst Way". crosswalk.com. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f White, Armond (December 15, 2009). "Blue in the face". New York Press. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- ^ a b Desjardins, Pierre (January 28, 2010). "Avatar: Nothing But a 'Stupid Justification for War!'". Le Monde. worldmeets.us. Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Marlowe, Ann (December 23, 2009). "The most neo-con movie ever made". Forbes. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- ^ Moore, Russell D. (December 21, 2009). "Avatar: Rambo in Reverse". The Christian Post.

- ^ a b c Podhoretz, John (December 28, 2009). "Avatarocious". The Weekly Standard. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- ^ a b Nolte, John (December 11, 2009). "REVIEW: Cameron's 'Avatar' Is a Big, Dull, America-Hating, PC Revenge Fantasy". bighollywood.breitbart.com. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ Mudede, Charles (January 4, 2010). "The globalization of Avatar". The Stranger Slog. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ Schlussel, Debbie (December 17, 2009). "Don't believe the hype: "Avatar" stinks (long, boring, unoriginal, uber-left)". Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ a b Murphy, Mekado (December 21, 2009). "A few questions for James Cameron". The Carpetbagger blog of The New York Times. Retrieved February 14, 2010.

- ^ Ditzian, Eric; Horowitz, Josh (February 18, 2010). "James Cameron responds to right-wing 'Avatar' critics". mtv.com. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ a b Adams, Sam (December 22, 2009). "Going Na'vi: Why Avatar's politics are more revolutionary than its images". The A.V. Club.

- ^ a b c d e Quinn, David (January 29, 2010). "Spirituality is real reason behind Avatar's success". Irish Independent. Retrieved February 12, 2010.

- ^ Oscar van den Boogaard. "What does avatar mean to you?". worldmeets.us. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ Matos, Altino (January 9, 2010). "Avatar holds out hope for something better". worldmeets.us. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ a b Osipov, Maxim (December 27, 2009). "What on Pandora does culture or civilisation stand for?". Hindustan Times. Retrieved December 27, 2009.

- ^ a b c Osipov, Maxim (January 04, 2010). "Avatar's reversal of fortune". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c "10 questions for James Cameron". Time magazine. March 4, 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ^ Linde, Harold (January 4, 2010). "Is Avatar radical environmental propaganda?". Mother Nature Network. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ a b c Pottinger, Lori (January 21, 2010). "Avatar: Should Brazil Ban the Film?". Huffington Post. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Liu, Milinda (February 4, 2010). "Confucius Says: Ouch — 'Avatar' trumps China's great sage". Newsweek. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ Thottam, Jyoti (February 13, 2010). "Echoes of Avatar: Is a Tribe in India the Real-Life Na'vi?". Time magazine. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ Hopkins, Kathryn (February 8, 2010). "Indian tribe appeals for Avatar director's help to stop Vedanta". The Guardian. Retrieved February 14, 2010.

- ^ Husser, Amy (March 5, 2010). "Environmentalists say Avatar's oilsands allegory deserves Oscar". Calgary Herald. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ "Oil industry disputes Avatar analogy". Edmonton Journal. March 5, 2010. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ Schmidt, Diane J. (February 17, 2010). "Avatar Unmasked: the real Na'vi and unobtanium". pej.org. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ Fischetti, Peter (March 6, 2010). "'Avatar' director wins different award from Temecula-area environmentalists". The Press-Enterprise (California). Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ a b "Avatar's story should frighten city developers". Global Times. January 7, 2010. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ a b Blinova, Yekaterina (January 22, 2010). "Krylatskiy Townspeople Treated Like Avatar Natives". Vedomosti (Russia). worldmeet.us. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ Boaz, David (January 26, 2010). "The right has Avatar wrong". Cato Institute. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ^ Zhou, Raymond (January 8, 2010). "Twisting Avatar to Fit China's Paradigm". China Daily. worldmeets.us. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ Washington, Jesse (January 11, 2010). "'Avatar' critics see racist theme". Associated Press. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ Žižek, Slavoj (March 4, 2010). "Return of the natives". New Statesman. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ Newitz, Annalee (December 18, 2009). "When Will White People Stop Making Movies Like "Avatar"". io9. Retrieved December 27, 2009.

- ^ Joffe, Josef (January 17, 2010). "Avatar: A Shameful Example of Western Cultural Imperialism". Die Zeit. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ a b Mardell, Mark (January 3, 2010). "Is blue the new black? Why some people think Avatar is racist". BBC. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ Brackman, Harold (December 30, 2009). "About avatars: Caveat emptor!". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ^ "Avatar 2009". goodnewsfilmreviews.com. December 20, 2009. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ Panyushkin, Valery (February 12, 2010). "Я — один из мерзавцев". Vedomosti (in Russian). Retrieved February 27, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Panyushkin, Valery (January 30, 2010). Vedomosti via translation by WorldMeets.US http://worldmeets.us/vedomosti000004.shtml. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Goldberg, Jonah (December 30, 2009). "Avatar and the faith instinct". National Review Online. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ Plate, S.Brent (January 28, 2010). "Something Borrowed, Something Blue: Avatar and the Myth of Originality". Religion Dispatches. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ^ Barnet, Vern (January 16, 2010). "'Avatar' upends many religious suppositions". Charlotte Observer. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ Himsel, Angela (February 19, 2010). "Avatar Meets Garden of Eden". Huffington Post. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ "Vatican critical of Avatar's spiritual message". CBC News. January 12, 2010. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ Douthat, Ross (December 21, 2009). "Heaven and Nature". New York Times. Retrieved December 21, 2009.

- ^ Outten, David (December 15, 2009). "Capitalism, Christianity and AVATAR". movieguide.org. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ Outten, David (January 29, 2010). "AVATAR Wins Golden Globe: Cameron Pushes Pantheism on TV". movieguide.org. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ "AVATAR: Get Rid of Human Beings Now!". movieguide.org. December 17, 2009. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ Palmer, Lane (December 23, 2009). "The True Avatar". Retrieved February 13, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Text "Chritsian Post" ignored (help) - ^ Milliner, Matthew (January 12, 2010). "Avatar and its Conservative Critics". thepublicdiscourse.com. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ a b c Hunt, Tam (January 16, 2010). "'Avatar,' blue skin and the ground of being". NoozHawk. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ Martinez, Dimentria (January 20, 2010). "Criticism of 'Avatar' spiritualism off base". National Catholic Reporter. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ Kazmi, Nikhat (December 17, 2009). "Avatar". The Times of India. Retrieved February 12, 2010.

- ^ a b c Lassin, Arlene (December 29, 2009). "New movie Avatar shines light on Hindu word". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|middle=ignored (help) - ^ Nayar, Parvathi (December 24, 2009). "Encounters of the weird kind". The Hindu. Retrieved February 12, 2010.

- ^ a b Wadhwani, Sita (December 24, 2009). "The religious backdrop to James Cameron's 'Avatar'". CNN Mumbai. Cable News Network Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- ^ a b French, Zenaida B. (March 1, 2010). "Two Critiques: 'Avatar' vis-à-vis 'Cinema Paradiso'". The News Today. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ Goodyear, Dana (October 26, 2009). "MAN OF EXTREMES: The return of James Cameron". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ Gereben, Janos (February 15, 2009). "Avatar, the prequel, at the Asian Art Museum". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ^ Mattingley, Terry (March 3, 2010). "A spiritual year at the multiplex". East Valley Tribune. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

External links

- Avatar (2009 film)

- Science fiction films

- Films about technology

- Environmental films

- Films about religion

- Films about reincarnation

- Colonialism

- Conservatism

- Anti-imperialism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-capitalism

- Racism

- Genocide

- Indigenous peoples

- Human rights abuses

- Hindu philosophical concepts

- Hindu deities

- Krishna

- Spirituality

- Pantheism

- Panentheism

- Nature goddesses

- Christianity

- Anti-Christianity

- Paganism

- Conquistadors