Spanish Civil War

| Spanish Civil War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| File:The El Campesino directing Republican soldiers at Villanueva de la Canada.jpg Republican troops at Villanueva | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

450,000 350 aircraft 200 batteries (1938)[1] |

600,000 600 aircraft 290 batteries (1938)[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~500,000[3][4] | |||||||

The Spanish Civil War was a major conflict that devastated Spain from 17 July 1936 to 1 April 1939. It began after an attempted coup d'état by a group of Spanish Army generals against the government of the Second Spanish Republic, then under the leadership of president Manuel Azaña. The nationalist coup was supported by the conservative Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right (Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas, or C.E.D.A), monarchists known as Carlist groups, and the Fascist Falange (Falange Española de las J.O.N.S.).[5] Following the partially successful coup, Spain was left divided as supporters of the existing Republican government fought the forces of the new Nationalist government for control of the country. The war ended with the victory of the Nationalists, the overthrow of the Republican government, and the founding of an authoritarian state led by General Francisco Franco. In the aftermath of the civil war, all right-wing parties were fused into the state party of the Franco regime.[5]

The Nationalists (nacionales) received the support of Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, as well as neighbouring Portugal.[6] The Communist Soviet Union intervened on the Republican side, although it encouraged factional conflict to the benefit of the Soviet foreign policy, and its actions may have been detrimental to the Republican war effort as a whole.[7] The United States government offered no official support for either side, although over two thousand Americans volunteered on the Republican side. Meanwhile, American corporations such as Texaco, General Motors, Ford Motors, and The Firestone Tire and Rubber Company greatly assisted the Nationalist army, furnishing a regular supply of trucks, tires, machine tools, and fuel.[8]

The war increased international tensions in Europe in the lead-up to World War II, and was largely seen as a proxy war between the Communist Soviet Union and Fascist states Italy and Germany. In particular, new tank warfare tactics and the terror bombing of cities from the air were features of the Spanish Civil War which played a significant part in the later general European war.[8]

The Spanish Civil War has been dubbed "the first media war", with several writers and journalists covering it wanting their work "to support the cause".[9] Foreign correspondents and writers covering it included Ernest Hemingway, Martha Gellhorn, George Orwell, Halfdan Rasmussen and Robert Capa. Like most international observers, they tended to support the Republicans, with some such as Orwell participating directly in the fighting.[10]

Like most civil wars, it became notable for the passion and political division it inspired, and for atrocities committed on both sides of the conflict. The Spanish Civil War often pitted family members, neighbors, and friends against each other. Apart from the combatants, many civilians were killed for their political or religious views by both sides, and after the war ended in 1939, the losing Republicans were persecuted by the victorious Nationalists.

An estimated total of more than 300,000 people lost their lives as a consequence of the war. Out of them probably more than 120,000 were civilians executed by either side.

Prelude to war

Historical context

There were several reasons for the war, many of them long-term tensions that had escalated over the years.

The 19th century was turbulent for Spain. The country had undergone several civil wars and revolts, carried out by both reformists and the conservatives, who tried to displace each other from power. A liberal tradition that first ascended to power with the Spanish Constitution of 1812 sought to abolish the monarchy of the old regime and to establish a liberal state. The most traditionalist sectors of the political sphere systematically tried to avert these reforms and to sustain the monarchy. The Carlists—supporters of Infante Carlos and his descendants—rallied to the cry of "God, Country and King" and fought for the cause of Spanish tradition (monarchy and Catholicism) against the liberalism – and later, the republicanism – of the Spanish governments of the day. The Carlists, at times (including the Carlist Wars), allied with nationalists (not to be confused with the nationalists of the Civil War) attempting to restore the historic liberties (and broad regional autonomy) granted by the fueros (regional charters) of the Basque Country and Catalonia. Further, from the mid-19th century onwards, liberalism was outflanked on its left by socialism of various types and especially by anarchism, which was far stronger in Spain than anywhere else in Europe.[11]

Spain experienced a number of different systems of rule in the period between the Napoleonic wars of the early 19th century and the outbreak of the Civil War. During most of the 19th century, Spain was a constitutional monarchy, but under attack from various directions. The First Spanish Republic, founded in 1873, was short-lived. A monarchy under Alfonso XIII lasted from 1887 to 1931, but from 1923 was held in place by the military dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera. Following Primo de Rivera's overthrow in 1930, the monarchy was unable to maintain power and the Second Spanish Republic was declared in 1931. This Republic soon came to be led by a coalition of the left and center. A number of controversial reforms were passed, such as the Agrarian Law of 1932, distributing land among poor peasants. Millions of Spaniards had been living in poverty under the firm control of the aristocratic landowners in a quasi-feudal system. These reforms created strong opposition from the landowners and the aristocrats. At the same time, the anticlericalist acts of the government infuriated the clergymen, while military cutbacks and reforms further alienated the military.

Constitution of 1931 and reform programme

On 14 April 1931 the Second Republic was declared in Spain.[12] Centuries of monarchical tradition - interrupted only by the brief interlude of 1873-74 - were abandoned. King Alfonso XIII left the country following local and municipal elections in which Republican candidates won the majority of votes in urban areas. The departure led to a provisional government under Niceto Alcalá Zamora, a Catholic and a landowner from Cordoba, and a constituent Cortes drew up a new constitution, which was adopted on 9 December 1931,[citation needed] after being passed by a referendum three days earlier.[citation needed] The Spanish Constitution of 1931 meant the legal beginning of the Second Spanish Republic, in which the election of both the positions of Head of State and Head of government was meant to be democratic.

The 1931 Constitution was formally effective from 1931 until 1939; however, in the spring of 1936, at the onset of the Spanish Civil War, it was largely abandoned by the Republicans in favor of leftist revolution.[13]

Spain entered the twentieth century a dominantly agrarian nation – a nation which, moreover, had lost its colonies. It was marked by uneven social and cultural development between town and country, between regions, within classes. 'Spain was not one country but a number of countries and regions marked by their uneven historical development.' [14] From the turn of the century, however, there had been a significant advance in industrial development. Between 1910 and 1930 the industrial working class more than doubled to over 2,500,000. Those engaged in agriculture fell from 66 per cent to 45 per cent in the same period. The coalition hoped to concentrate its major reforms on three sectors : the 'latifundist aristocracy', the church and the army – though the attempt would come at a moment of world economic crisis. In the south less than 2 per cent of all landowners had over two thirds of the land, while 750,000 labourers eked out a living on near starvation wages. The country was 'prone to centrifugal tendencies', for example there was a tension between Catalan and Basque nationalist sentiment away from an agrarian and centralist ruling class in Madrid.[15] While the coalition held political power, economic power escaped it. In historian Hugh Thomas's words, 'Like so many others before and since it frightened the middle class without satisfying the workers.' It adopted the measures of separation of church and state, genuine universal suffrage, a cabinet responsible to a single chamber parliament, a secular educational system. This last measure antagonised the Church. The coalition's religious policy attacked an important area of the status quo's ideological dominance: religious education. Just fifteen days after the announcement of the Republic , Cardinal Pedro Segura, the primate of Spain, issued a pastoral denouncing the new government's intention to establish freedom of worship and to separate Church and State. The cardinal urged Catholics to vote in future elections against an administration which in his view wanted to destroy religion.[16] It excluded the Church from education (prohibited teaching by religious orders, even in private schools), restricted Church property rights and investments, provided for confiscation of and prohibitions on ownership of Church property, and banned the Society of Jesus.[17][18] The revolution of 1931 that established the Second Republic brought to power an anticlerical government.[19]

The government was unable to control the anti-Catholic sentiment and deadly mob attacks on churches and monasteries[19]. That caused Catholics to muster their forces in opposition, exacerbating the conditions that led to the war.

On 3 June 1933, in the encyclical Dilectissima Nobis (On Oppression Of The Church Of Spain), Pope Pius XI condemned the Spanish Government's deprivation of the civil liberties on which the Republic was supposedly based, noting in particular the expropriation of Church property and schools and the persecution of religious communities and orders.[20]

Commentators have posited that the "hostile" approach to the issues of church and state was a substantial cause of the breakdown of democracy and the onset of civil war.[21][22] Since the far left considered moderation of the anticlericalist aspects of the constitution as totally unacceptable, commentators have argued that "the Republic as a democratic constitutional regime was doomed from the outset".[23]

1933 election and aftermath

In the 1933 elections to the Cortes Generales, the Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right (Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas or CEDA) won a plurality of seats; however, these were not enough to form a majority. Despite the results, then President Niceto Alcalá-Zamora declined to invite the leader of the CEDA to form a government and instead invited the Radical Republican Party and its leader Alejandro Lerroux to do so. CEDA supported the Lerroux government; it later demanded and, on 1 October 1934, received three ministerial positions.

Lerroux's alliance with the right, his suppression of the revolt in 1934, and the Stra-Perlo scandal combined to leave him and his party with little support going into the 1936 election; Lerroux lost his seat in parliament.

Rising tensions and political violence

Hostility between the left and the right increased after the 1933 formation of the Government. Spain experienced general strikes and street conflicts. Noted among the strikes was the miners' revolt in northern Spain and riots in Madrid. Nearly all rebellions were crushed by the Government and political arrests followed.

Tensions rose in the period before the start of the war. Radicals became more aggressive, and conservatives turned to paramilitary and vigilante actions. According to official sources, 330 people were assassinated and 1,511 were wounded in political violence; records show 213 failed assassination attempts, 113 general strikes, and the destruction (typically by arson) of 160 religious buildings.[24]

1936 Popular Front victory and aftermath

In the 1936 Elections a new coalition of Socialists (Spanish Worker Socialist Party, PSOE), liberals (Republican Left and the Republican Union Party), Communists, and various regional nationalist groups won the extremely tight election. The results gave 34 percent of the popular vote to the Popular Front and 33 percent to the incumbent government of the CEDA. This result, when coupled with the Socialists' refusal to participate in the new government, led to a general fear of revolution.

Azaña becomes president

Without the Socialists, Prime Minister Manuel Azaña, a liberal who favored gradual reform while respecting the democratic process, led a minority government. In April, parliament replaced President Niceto Alcalá-Zamora with Azaña. The removal of Zamora was made on specious grounds using a constitutional technicality.[25] Although the right also voted for Zamora's removal, this was a watershed event which inspired many conservatives to give up on parliamentary politics.[citation needed] Azaña had found that by spring of 1936 the left was using its influence to circumvent the Republic and the constitution and was adamant about increasingly radical changes.[26] Leon Trotsky wrote that Zamora had been Spain's "stable pole", and his removal made the climate revolutionary.[27]

Azaña was the object of intense hatred by Spanish rightists because he had pushed a reform agenda through a recalcitrant parliament in 1931–1933. Joaquín Arrarás, a friend of Francisco Franco, called him "a repulsive caterpillar of red Spain."[28] The Spanish generals particularly disliked Azaña because he had cut the army's budget and closed the military academy while war minister (1931). CEDA turned its campaign chest over to army plotter Emilio Mola. Monarchist José Calvo Sotelo replaced CEDA's Gil Robles as the right's leading spokesman in parliament.[28]

Murder of Calvo Sotelo

José Calvo Sotelo was the leading Spanish monarchist and a prominent parliamentary conservative. He protested against what he viewed as escalating anti-religious terror, expropriations, and hasty agricultural reforms, which he considered Bolshevist and anarchist. He instead advocated the creation of a corporative state.[29]

On 12 July 1936, in Madrid, a far right group murdered Lieutenant José Castillo of the Assault Guards (a special police corps created to deal with urban violence) and a Socialist. The next day, Assault Guards with forged papers "arrested" Calvo Sotelo and abducted him in an Assault Guard van.[30] Leftist gunman Luis Cuenca, who was operating in a commando unit of the Assault Guard led by Captain Fernando Condés Romero, is said to have murdered Calvo Sotelo. Condés was close to the Socialist leader Indalecio Prieto, and Cuenca was one of Prieto's bodyguards.

The murder of such a prominent member of parliament, with involvement of the police, aroused suspicions and strong reactions among the Center and the Right.[31] Although the Nationalist generals, with a plane en route to take Francisco Franco to the Army of Africa,[32] were already in advanced stages of a planned uprising, the event provided a catalyst and convenient public justification for their coup.

Outbreak of the war

Nationalist military revolt

The monarchist General José Sanjurjo was the figurehead of the rebellion, while Emilio Mola was chief planner and second in command.[28] Mola began serious planning in the spring, but General Francisco Franco hesitated until early July, inspiring other plotters to refer to him as "Miss Canary Islands 1936".[28] Franco was a key player because of his prestige as a former director of the military academy and as the man who suppressed the Socialist uprising of 1934.[28]

Fearing a military coup, Prime Minister Casares Quiroga sent General Manuel Goded Llopis to the Balearic Islands and Franco to the Canary Islands. On 17 July 1936, the plotters signaled the beginning of the coup by broadcasting the code phrase, "Over all of Spain, the sky is clear." Llopis and Franco immediately took control of the islands to which they were assigned. Warned that a coup was imminent, leftists barricaded the roads on 17 July, but Franco avoided capture by taking a tugboat to the airport.[28]

Two British MI6 intelligence agents, Cecil Bebb and Major Hugh Pollard, then flew Franco to Spanish Morocco[33] to see Juan March Ordinas, where the Spanish Army of Africa, led by Nationalist officers, was unopposed.

Government reaction

The rising was intended to be a swift coup d'état, but was botched in certain areas allowing the government to retain control of parts of the country. At this first stage, the rebels failed to take any major cities—in Madrid they were hemmed into the Montaña barracks. The barracks fell the next day, with much bloodshed. In Barcelona, anarchists armed themselves and defeated the rebels. General Goded Llopis, who arrived from the Balearic islands, was captured and later executed. However, the turmoil facilitated anarchist control over Barcelona and much of the surrounding Aragonese and Catalan countryside, effectively breaking away from the Republican government and establishing anarchism in Catalonia. According to Noam Chomsky:

When the coup came, the Republican government was paralyzed. Workers armed themselves in Madrid and Barcelona, robbing government armories and even ships in the harbor, and put down the insurrection while the government vacillated, torn between the twin dangers of submitting to Franco and arming the working classes. In large areas of Spain effective authority passed into the hands of the anarchist and socialist workers who played a substantial, generally dominant role in putting down the insurrection.[34]

The Republicans held on to Valencia and controlled almost all of the Eastern Spanish coast and central area around Madrid. Except for Asturias, Cantabria and part of the Basque Country, the Nationalists took most of northern and northwestern Spain and also a southern area in central and western Andalusia including Seville.

Combatants

The war was cast by Republican sympathizers as a struggle between "tyranny and democracy", and by Nationalist supporters as between Communist and anarchist "red hordes" and "Christian civilization". Nationalists also claimed to be protecting the establishment and bringing security and direction to an ungoverned and lawless society.[35]

The active participants in the war covered the entire gamut of the political positions of the time. The Nationalist (nacionales) side included the Carlists and Legitimist monarchists, Spanish nationalists, the Falange, and most conservatives and monarchist liberals, Virtually all Nationalist groups had very strong Catholic convictions and supported the native Spanish clergy. On the Republican side were Marxists, liberals, and anarchists.

Spanish politics, especially on the left, were quite fragmented. At the beginning, socialists and radicals supported democracy, while the communists and anarchists opposed the institution of the republic as much as the monarchists. There were internal divisions even among the socialists: a group that adhered to classical Marxism, and a more progressive Marxist group. The former was the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE), one of whose delegates to the Soviet Union challenged Stalin regarding his use of the CHEKA to rein in dissidents, and upon his return to Spain convinced the PSOE to reject affiliation with the 5th to 7th Comintern.[36] From the Comintern's point of view the increasingly powerful, if fragmented, left and the weak right were an optimum situation.[37] Their goal was to use a veil of legitimate democratic institutions to outlaw the right, converting the state into the Soviet vision of a "people's republic" with total leftist domination, a goal repeatedly voiced in Comintern instructions and in the public statements of the PCE (Communist Party of Spain).[37] The left and Basque or Catalan nationalist conservatives had many conflicting ideas. The Cortes (Spanish Parliament) consisted of 16 parties in 1931. An attempt by the communists to seize control resisted by anarchists resulted in the massacre of hundreds of rebels and civil war between communists and anarchists in Catalonia.

The actions of the Republican government slowly coagulated the different people on the right.[38]

The Nationals included the majority of the Catholic clergy and of practicing Catholics (outside of the Basque region), important elements of the army, most of the large landowners, and many businessmen. The Republicans included most urban workers, most peasants, and much of the educated middle class, especially those who were not entrepreneurs.

Republicans

Republicans (also known as Spanish loyalists) received weapons and volunteers from the Soviet Union, Mexico, the international Marxists movement and the International Brigades. The Republicans ranged from centrists who supported a moderately capitalist liberal democracy to revolutionary anarchists; their power base was primarily secular and urban, but also included landless peasants, and it was particularly strong in industrial regions like Asturias and Catalonia.[39] This faction was called variously the "loyalists" by its supporters; the "Republicans", "the Popular Front" or "the Government" by all parties; and "the reds" by its enemies. Regarding the term "loyalist", Historian Stanley Payne notes: "the adjective "loyalist" is somewhat misleading, for there was no attempt to remain loyal to the constitutional Republican regime. If that had been the scrupulous policy of the left, there would have been no revolt and civil war in the first place."[13]

The conservative, strongly Catholic Basque country, along with Galicia and the more left-leaning Catalonia, sought autonomy or even independence from the central government of Madrid. This option was left open by the Republican government.[40] All these forces were gathered under the People's Republican Army (Ejército Popular Republicano, or EPR) .

Nationalists

The Nationalists (also called "insurgents", "rebels" or by opponents "Francoists" or overinclusively as "Fascists") fearing national fragmentation, opposed the separatist movements, and were chiefly defined by their anti-communism, which galvanized diverse or opposed movements like falangists or monarchists. Their leaders had a generally wealthier, more conservative, monarchist, landowning background, and (with the exception of the Carlists) favoured the centralization of state power.

One of the Nationalists' principal stated motives was to confront the anti-clericalism of the Republican regime and to defend the Church, which had been the target of attacks, and which many on the Republican side blamed for the ills of the country. Even before the war, in the Asturias uprising of 1934 religious buildings were burnt and at least 100 clergy, religious, and police were killed in cold blood, but the president and the radicals prevented the implementation of any serious sanctions against the revolutionaries.[25][41][42] According to Payne:

More than 1,000 were killed, the majority revolutionaries, and there were atrocities on both sides. The revolutionaries shot nearly 100 people in cold blood, most of them policemen and priests, and an almost equal number of rebels--possibly even more--were executed out of hand by the troops that suppressed the revolt.[25]

Articles 24 and 26 of the Constitution of the Republic had banned the Jesuits, which deeply offended many within the conservatives. The revolution in the republican zone at the outset of the war, killing 7,000 clergy and thousands of lay people, drove many Catholics, left then with little alternative, to the Nationalists.[43][44]

Other factions

Catalan and Basque nationalists were not univocal. Left-wing Catalan nationalists were on the Republican side. Conservative Catalan nationalists were far less vocal supporting the Republican government due to the anti-clericalism and confiscations occurring in some areas controlled by the latter (some conservative Catalan nationalists like Francesc Cambó actually funded the Nationalist side). Basque nationalists, heralded by the conservative Basque nationalist party, were mildly supportive of the Republican government, even though Basque nationalists in Álava and Navarre sided with the uprising for the same reasons influencing Catalan conservative nationalists. Notwithstanding the religious matters, the Basque nationalists, who nearly all sided with the Republic, were, for the most part, practicing Catholics.

Foreign involvement

The Spanish Civil War had large numbers of non-Spanish citizens participating in combat and advisory positions. Foreign governments contributed large amounts of financial assistance and military aid to forces led by Franco. Forces fighting on behalf of the Republicans also received limited aid, but support was seriously hampered by the arms embargo declared by France and the UK. These embargoes were never very effective however, and France especially was accused of allowing large shipments through to the Republicans (but the accusations often came from Italy, itself heavily involved for the Nationalists). The clandestine actions of the various European powers were at the time considered to be risking another 'Great War'.[45]

The League of Nations' reaction to the war was mostly neutral and insufficient to contain the massive importation of arms and other war resources by the fighting factions. Although a Non-Intervention Committee was created, its policies were largely ineffective. Its directives were dismantled due to the policies of appeasement of both European democratic and non-democratic powers of the late 1930s: the official Spanish government of Juan Negrín was gradually abandoned within the organization during this period.[46]

Support for Nationalists

Despite the Irish government's prohibition against participating in the war, around 700 Irishmen, followers of Eoin O'Duffy known as "Blueshirts", went to Spain to fight on Franco's side. The Nationalists received weapons and logistical support from Portugal. In addition approximately 8,000 Portuguese volunteers, known as Viriatos after an aborted national legion that failed to get off the ground in the early months of the war, fought in Franco's forces.[47] Romanian volunteers were led by Ion I Moţa, deputy-leader of the Legion of the Archangel Michael (or Iron Guard), whose group of seven Legionaries visited Spain in December 1936 to ally their movement to the Nationalists.[48] Moţa was killed in action at Majadahonda on January 13, 1937.[49]

Germany

Francisco Franco asked Adolf Hitler from Nazi Germany and Benito Mussolini from Fascist Italy to aid the Nationalists. Hitler agreed and ordered three major military operations in Spain during the Spanish Civil War. He authorized Operation Feuerzauber ("Fire Magic") in late July 1936. He mobilized 20 three-motor Junkers Ju 52 planes with six escort fighters, 85 Germans on the SS Usaramo ship to work on the planes, and transferred German troops stationed in Morocco to Spain. A few months later in late September, Hitler again mobilized men and materials to aid Franco for Operation Otto. He sent 24 more Panzer I light tanks, a flak, and some radio equipment. German commander Major Alexander von Scheele also converted the Junkers 52s to bombers.[50] By October, there were an estimated 600–800 German soldiers in Spain.[50] Hitler’s largest and last move was the Condor Legion (Legion Condor). Initiated in November 1936, he sent an additional 3,500 troops into combat and supplied the Spanish Nationalists with 92 new planes.[50] Hitler kept the Condor Legion in Spain until the end of the war in May 1939. At its zenith, The German force numbered about 12,000 men, and as many as 19,000 Germans fought in Spain. In total Nazi Germany provided Nationalists with 600 planes, 200 tanks, and 1,000 artillery pieces.[51]

Italy

After Franco’s request and in response to Adolf Hitler's encouragement, Benito Mussolini joined the war, partly because he did not want to be outdone by Hitler.[50] While Mussolini sent more ground troops than Hitler, he initially supplied fewer materials. At the beginning of war in September 1936, Mussolini had only supplied 68 aircraft and several hundred small arms to the Nationalists.[50] However, the Royal Italian Navy (Regia Marina Italiana) played a major role in the Mediterranean blockade and ultimately Italy supplied machine guns, artillery, aircraft, tankettes, the "Legionary Air Force" (Aviazione Legionaria), and the "Corps of Volunteer Troops" (Corpo Truppe Volontarie, or CTV).[52] The Italian CTV reached a high of about 50,000 men and, by rotation, more than 75,000 Italians were to fight for the Nationalists in Spain. In total fascist Italy provided Nationalists with 660 planes, 150 tanks and 1,000 artillery pieces.[51]

Portugal

Salazar's Estado Novo played a most important role in supplying Franco’s forces with ammunition and many other logistical resources.[53] Despite its discrete direct military involvement — restrained to a somewhat "semi-official" endorsement, by its authoritarian regime, of an 8,000–12,000-strong volunteer force,[54] the so-called "Viriatos" — for the whole duration of the conflict, Portugal was instrumental in providing the Nationalists with a vital logistical organization and by reassuring Franco and his allies that no interference whatsoever would hinder the supply traffic directed to the Nationalists, crossing the borders of the two Iberian countries — the Nationalists used to refer to Lisbon as "the port of Castile".[55]

Support for Republicans

International Brigades

Many non-Spanish people, often affiliated with radical, communist or socialist parties or groups, joined the International Brigades, believing that the Spanish Republic was the front line of the war against fascism. The troops of the International Brigades represented the largest foreign contingent of those fighting for the Republicans. Roughly 30,000 foreign nationals from up to 53 nations fought in the brigades. Most of them were communists or trade unionists, and while organised by communists guided or controlled by Moscow, they were almost all individual volunteers.

Likely respectively more than 1,000 volunteers came from France, Italy, Germany, Poland, USSR, USA, UK, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Ireland, Yugoslavia, Hungary and Canada. The Thälmann Battalion was a group of German, Swiss, Austrian and Scandinavian volunteers who distinguished themselves during the Siege of Madrid. The American volunteers fought in units such as the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and Canadians in the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion.

Over five hundred Romanians fought on the Republican side, including Romanian Communist Party members Petre Borilă and Valter Roman.[56]

Some Chinese joined the international brigades. At the end of the war, the majority returned to China, while some went to prison, others went to refugee camps in southern France, and a handful remained in Spain, including about ten who married Spanish women.[57]

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union primarily provided material assistance to the Republican forces. In total the USSR provided Spain with 806 planes, 362 tanks, and 1,555 artillery pieces. [58] The Soviet Union ignored the League of Nations embargo and sold arms to the Republic when few other nations would do so; thus it was the Republic's only important source of major weapons. Stalin had signed the Non-Intervention Agreement but decided to break the pact. However, unlike Hitler and Mussolini who openly violated the pact, Stalin tried to do so secretly.[59] He created a section X of the Soviet Union military to head the operation, coined Operation X. However, while a new branch of the military was created especially for Spain, most of the weapons and artillery sent to Spain were antiques. Stalin did not want the arms to be traceable to the Soviet Union, so most were taken from museums from around the country. He also used weapons captured from past conflicts[59]. However, modern weapons such as BT-5 tanks and I-16 fighter aircraft were also supplied to Spain.

Many of the Soviet’s deliveries were lost or smaller than Stalin had ordered. He only gave short notice, which meant many weapons were lost in the delivery process[59]. Lastly, when the ships did leave with supplies for the Republicans, the journey was extremely slow. Stalin ordered the builders to include false decks in the original design of the boat. Then, once the ship left shore it was required to change its flag and change the color of parts of the ship to minimize capture by the Nationalists[59]. However in 1938, Stalin withdrew his troops and tanks as government ranks floundered.

The Republic had to pay for Soviet arms with the official gold reserves of the Bank of Spain, in an affair that would become a frequent subject of Francoist propaganda afterward (see Moscow Gold). The cost to the Republic of Soviet arms was more than US $500 million, two-thirds of the gold reserves that Spain had at the beginning of the war.[citation needed]

The Soviet Union also sent a number of military advisers to Spain (2,000[60]-3,000[61]).[62] While Soviet troops amounted to no more than 700 men, Soviet "volunteers" often operated Soviet-made Republican tanks and aircraft.[citation needed] In addition, the Soviet Union directed Communist parties around the world to organize and recruit the International Brigades.

Another significant Soviet involvement was the pervasive activities of the NKVD all along the Republican rearguard. Communist figures like Vittorio Vidali ("Comandante Contreras"), Iosif Grigulevich and, above all, Alexander Orlov led those not-so-secret operations, that included murders like those of Andreu Nin and José Robles.

Mexico

Unlike the United States and major Latin American governments such as those of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Peru, the Mexican government supported the Republicans. Mexico refused to follow the French-British non-intervention proposals, but Mexican aid meant little compared to the quantities supplied to the Nationalists by Italy and Germany. Mexico furnished $2,000,000 in aid and provided some material assistance, which included 20,000 rifles, 28 million cartridges, 8 artillery pieces and small number of American-made aircraft such as the Bellanca CH-300 and Spartan Zeus that served in the Mexican Air Force.

However, Mexico's most important contributions to the Spanish Republic were diplomatic and to provide sanctuary for Republican refugees including many Spanish intellectuals and orphaned children from Republican families.

Chronology

1936

Coup leader Sanjurjo was killed in a plane crash on 20 July, leaving an effective command split between Mola in the North and Franco in the South.[28] On 21 July, the fifth day of the rebellion, the Nationalists captured the main Spanish naval base at Ferrol in northwestern Spain. A rebel force under Colonel Beorlegui Canet, sent by General Emilio Mola, undertook the Campaign of Guipúzcoa from July to September. The capture of Guipúzcoa isolated the Republican provinces in the north. On 5 September, after heavy fighting the force took Irún, closing the French border to the Republicans. On 13 September, the Basques surrendered San Sebastián to the Nationalists, who then advanced toward their capital, Bilbao. The Republican militias on the border of Vizcaya halted these forces at the end of September.

Franco was chosen overall Nationalist commander at a meeting of ranking generals at Salamanca on 21 September.[28] Franco won another victory on 27 September when they relieved the Alcázar at Toledo. A Nationalist garrison under Colonel Moscardo had held the Alcázar in the center of the city since the beginning of the rebellion, resisting thousands of Republican troops who completely surrounded the isolated building. The Republic's inability to take the Alcázar was a serious blow to its prestige in view of its overwhelming numerical superiority in the area. Two days after relieving the siege, Franco proclaimed himself Generalísimo and Caudillo ("chieftain"), while forcibly unifying the various and diverse Falangist, Royalist and other elements within the Nationalist cause.

In October, the Francoist troops launched a major offensive toward Madrid, reaching it in early November and launching a major assault on the city on 8 November. The Republican government was forced to shift from Madrid to Valencia, out of the combat zone, on 6 November. However, the Nationalists' attack on the capital was repulsed in fierce fighting between 8 November and 23 November. A contributory factor in the successful Republican defense was the arrival of the International Brigades, though only around 3,000 of them participated in the battle. Having failed to take the capital, Franco bombarded it from the air and, in the following two years, mounted several offensives to try to encircle Madrid.

1937

With his ranks swelled by Italian troops and Spanish colonial soldiers from Morocco, Franco made another attempt to capture Madrid in January and February 1937, but again failed.

On 21 February the League of Nations Non-Intervention Committee ban on foreign national "volunteers" went into effect. The large city of Málaga was taken on 8 February. On 7 March, the German Condor Legion equipped with Heinkel He 51 biplanes arrived in Spain; on 26 April the Legion bombed the town of Guernica, killing hundreds. Two days later, Franco's army overran the town.

After the fall of Guernica, the Republican government began to fight back with increasing effectiveness. In July, they made a move to recapture Segovia, forcing Franco to pull troops away from the Madrid front to halt their advance. Mola, Franco's second-in-command, was killed on 3 June, and in early July, despite the fall of Bilbao in June, the government launched a strong counter-offensive in the Madrid area, which the Nationalists repulsed with difficulty. The clash was called "Battle of Brunete" after a town in the province of Madrid.

Franco invaded Aragón in August and then took the city of Santander. With the surrender of the Republican army in the Basque territory and after two months of bitter fighting in Asturias (Gijón finally fell in late October) Franco had effectively won in the north. At the end of November, with Franco's troops closing in on Valencia, the government had to move again, this time to Barcelona.

1938

The Battle of Teruel was an important confrontation. The city belonged to the Nationalists at the beginning of the battle, but the Republicans conquered it in January. The Francoist troops launched an offensive and recovered the city by 22 February, but in order to do so Franco relied heavily on German and Italian air support and repaid them with extensive mining rights.[63]

On 7 March, the Nationalists launched the Aragon Offensive. By 14 April, they had pushed through to the Mediterranean, cutting the Republican-held portion of Spain in two. The Republican government tried to sue for peace in May,[64] but Franco demanded unconditional surrender; the war raged on. In July, the Nationalist army pressed southward from Teruel and south along the coast toward the capital of the Republic at Valencia but was halted in heavy fighting along the XYZ Line, a system of fortifications defending Valencia.

The Republican government then launched an all-out campaign to reconnect their territory in the Battle of the Ebro, from 24 July until 26 November. The campaign was unsuccessful, and was undermined by the Franco-British appeasement of Hitler in Munich with the concession of Czechoslovakia. This effectively destroyed Republican morale by ending hope of an anti-fascist alliance with the Western powers. The retreat from the Ebro all but determined the final outcome of the war. Eight days before the new year, Franco threw massive forces into an invasion of Catalonia.

1939

Franco's troops conquered Catalonia in a whirlwind campaign during the first two months of 1939. Tarragona fell on 14 January, followed by Barcelona on 26 January and Girona on 5 February. Five days after the fall of Girona, the last resistance in Catalonia was broken.

On 27 February, the United Kingdom and France recognized the Franco regime.

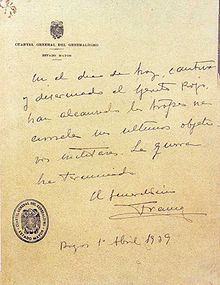

Only Madrid and a few other strongholds remained for the Republican forces. Then, on 28 March, with the help of pro-Franco forces inside the city, Madrid fell to the Nationalists. The next day, Valencia, which had held out under their guns for close to two years, also surrendered. Franco proclaimed victory in a radio speech aired on 1 April, when the last of the Republican forces surrendered.

After the end of the War, there were harsh reprisals against Franco's former enemies;[65] thousands of Republicans were imprisoned and at least 30,000 executed.[66] Other calculations of these deaths range from 50,000[67] to 200,000. Many others were put to forced labour, building railways, drying out swamps, digging canals, etc.

Hundreds of thousands of Republicans fled abroad, some 500,000 to France.[68] Refugees were confined in internment camps of the French Third Republic, such as Camp Gurs or Camp Vernet, where 12,000 Republicans were housed in squalid conditions. Of the 17,000 refugees housed in Gurs, the farmers and ordinary people who could not find relations in France were encouraged by the Third Republic, in agreement with the Francoist government, to return to Spain. The great majority did so and were turned over to the Francoist authorities in Irún. From there they were transferred to the Miranda de Ebro camp for "purification" according to the Law of Political Responsibilities. After the proclamation by Marshal Philippe Pétain of the Vichy regime, the refugees became political prisoners, and the French police attempted to round up those who had been liberated from the camp. Along with other "undesirables", they were sent to the Drancy internment camp before being deported to Nazi Germany. About 5,000 Spaniards thus died in Mauthausen concentration camp.[69]

After the official end of the war, guerrilla war was waged on an irregular basis well into the 1950s, being gradually reduced by military defeats and scant support from the exhausted population. In 1944, a group of republican veterans, who also fought in the French resistance against the Nazis, invaded the Val d'Aran in northwest Catalonia, but were defeated after ten days.

Evacuation of children

As war proceeded in the Northern front, the Republican authorities arranged the evacuation of children. These Spanish War children were shipped to Britain, Belgium, the Soviet Union, other European countries and Mexico. Those in Western European countries returned to their families after the war, but many of those in the Soviet Union, from Communist families, remained and experienced the Second World War and its effects on the Soviet Union.

The Nationalist side also arranged evacuations of children, women and elderly from war zones. Refugee camps for those civilians evacuated by the Nationalists were set up in Portugal, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium.

Atrocities

At least 50,000 people were executed during the war.[70][71] In his updated history of the Spanish Civil War, Antony Beevor writes, "Franco's ensuing 'white terror' claimed 200,000 lives. The 'red terror' had already killed 38,000."[72] Julius Ruiz concludes that "although the figures remain disputed, a minimum of 37,843 executions were carried out in the Republican zone with a maximum of 150,000 executions (including 50,000 after the war) in Nationalist Spain."[73] César Vidal puts the number of Republican victims at 110,965.[74] In 2008 a Spanish judge, Baltasar Garzón, opened an investigation into the executions and disappearances of 114,266 people between 17 July 1936 and December 1951 (he has since been indicted for violating a 1977 amnesty by these actions). Among the executions investigated was that of the poet and dramatist Federico García Lorca.[3][75]

In the early days of the war, executions of people who were caught on the "wrong" side of the lines became widespread in conquered areas. The outbreak of the war provided an excuse for settling accounts and resolving longstanding feuds. In these paseos ("strolls"), as the executions were called, the victims were taken from their refuges or jails to be shot outside of town. The corpses were abandoned or interred in graves dug by the victims themselves. Local police just noted the appearance of the corpses.

Nationalists

The atrocities of the Nationalists, frequently ordered by authorities in order to eradicate any trace of leftism in Spain, were common. According to historian Paul Preston, the minimum number of those executed by the rebels is 130,000, and is likely to be far higher. The violence carried out in the rebel zone was carried out by the military, the "Civil Guard", the Falange in the name of the regime and legitimized by the Catholic Church.[76]

Many such acts were committed by reactionary groups during the first weeks of the war. This included the execution of school teachers[77] (because the efforts of the Second Spanish Republic to promote laicism and to displace the Church from the education system by closing religious schools were considered by the Nationalists side as an attack on the Roman Catholic Church); the massive killings of civilians in the cities they captured;[78] the execution of unwanted individuals (including non-combatants[79] such as trade-unionists and known Republican sympathisers etc).[80]

Nationalist forces committed massacres in Seville, where some 10,000 people were shot. In Granada, about 8000 people were murdered.[81]. After the capture of Almendralejo, about 1000 prisoners were shot, including 100 women. Some 2000 were shot when Badajoz was conquered by Yague. In February 1937, over 4000 were killed after the capture of Malaga. When Bilbao was conquered, some 1000 people were executed.[82] The numbers of people killed as the African columns raped, looted, and murdered their way through Seville and Madrid are particularly difficult to calculate.[83]

Nationalists murdered Catholic clerics. In one particular incident, following the capture of Bilbao, hundreds of people, including 16 priests who had served as chaplains for the Republican forces, were taken to the countryside or to graveyards to be murdered.[84]

Franco's forces persecuted Protestants. They murdered Protestant ministers. Franco's forces were determined to remove from Spain the "Protestant heresy". Pastor Miguel Blanco of Seville was shot as was Pastor Jose Garcia Fernandez of Granada. In Zaragoza, on August 18, the church was attacked by Franco's forces. They destroyed furniture, burned Bibles and books and stole valuables. Many Protestants were imprisoned and tortured.[85]

The Nationalists also persecuted the Basque people. They were determined to eradicate Basque culture. According to Basque sources, some 22,000 Basques were murdered by Nationalists immediately after the Civil War.[86]

The Nationalist side also conducted aerial bombing of cities in Republican territory, carried out mainly by the Luftwaffe volunteers of the Condor Legion and the Italian air force volunteers of the Corpo Truppe Volontarie (Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, Guernica, and other cities). The most notorious example of this tactic of terror bombings was the Bombing of Guernica.

Republicans

An estimated 55,000 civilians died in Republican-held territories. Some were executed as suspected fifth columnists. Others died in revenge due to news of the massacres carried out in the Nationalist zone. Air raids committed against Republican cities were another factor.[89] Historian Paul Preston emphasizes that Republican authorities did not order such measures to be taken.[76] Nearly all segments of the Republicans, Basques being a notable exception took part in semi-organized anticlerical killing of 6,832 members of the Catholic clergy and religious orders.[90][91] By the end of the war 20% percent of the nation's clergy had been killed.[92]

Republicans initially reacted to the attempted coup by arresting and executing actual and perceived Nationalists. In the Andalusian town of Ronda, 512 alleged Nationalists were executed in the first month of the war.[93]

Communist Santiago Carrillo Solares have been accused of the killing of Nationalists in the Paracuellos massacre near Paracuellos del Jarama and Torrejón de Ardoz. However, the extent to which (in particular) Carrillo was responsible remains a source of debate.[94] Communists committed numerous atrocities against fellow Republicans: André Marty, known as the Butcher of Albacete, was responsible for the deaths of some 500 members of the International Brigades,[95] and Andreu Nin, leader of the POUM, and many prominent POUM members were murdered by the Communists.[96]

Social revolution

In the anarchist-controlled areas, Aragón and Catalonia, in addition to the temporary military success, there was a vast social revolution in which the workers and peasants collectivised land and industry, and set up councils parallel to the paralyzed Republican government. This revolution was opposed by both the Soviet-supported communists, who ultimately took their orders from Stalin's politburo (which feared a loss of control), and the Social Democratic Republicans (who worried about the loss of civil property rights). The agrarian collectives had considerable success despite opposition and lack of resources.[97]

As the war progressed, the government and the communists were able to leverage their access to Soviet arms to restore government control over the war effort, through both diplomacy and force. Anarchists and the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista, or POUM) were integrated into the regular army, albeit with resistance; the POUM was outlawed and falsely denounced as an instrument of the fascists. In the May Days of 1937, many hundreds or thousands of anti-fascist soldiers fought for control of strategic points in Barcelona.

The pre-war Falange was a small party of some 30–40,000 members. It also called for a social revolution that would have seen Spanish society transformed by National Syndicalism. Following the execution of its leader, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, by the Republicans, the party swelled in size to over 400,000. The leadership of the Falange suffered 60% casualties in the early days of the civil war and the party was transformed by new members and rising new leaders, called camisas nuevas ("new shirts"), who were less interested in the revolutionary aspects of National Syndicalism.[98] Subsequently, Franco united all rightist parties into the ironically named Falange Española Tradicionalista de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional-Sindicalista (FET y de las JONS), or the Traditionalist Spanish Falange of the Unions of the National-Syndicalist Offensive.

The 1930s also saw Spain become a focus for pacifist organizations including the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the War Resisters League and the War Resisters' International. Many people including, as they are now called, the 'insumisos' ('defiant ones', conscientious objectors) argued and worked for non-violent strategies. Prominent Spanish pacifists such as Amparo Poch y Gascón and José Brocca supported the Republicans. Brocca argued that Spanish pacifists had no alternative but to make a stand against fascism. He put this stand into practice by various means including organizing agricultural workers to maintain food supplies and through humanitarian work with war refugees.[99]

People

Template:Important Figures in the Spanish Civil War

Political parties and organizations

| The Popular Front (Republican) | Supporters of the Popular Front (Republican) | Nationalists (Francoist) |

|---|---|---|

|

The Popular Front was an electoral alliance formed between various left-wing and centrist parties for elections to the Cortes in 1936, in which the alliance won a majority of seats.

|

|

Virtually all Nationalist groups had very strong Roman Catholic convictions and supported the native Spanish clergy.

|

See also

- Guernica (painting)

- The Falling Soldier

- List of war films and TV specials#Spanish Civil War (1936–1939)

- List of foreign correspondents in the Spanish Civil War

- Ireland and the Spanish Civil War

- Polish volunteers in the Spanish Civil War

- Jewish volunteers in the Spanish Civil War

- Proxy war

- European Civil War

- Spain in World War II

- Moscow Gold

- Surviving veterans of the Spanish Civil War

- SS Cantabria

- Nationalist Foreign Volunteers

- Pacifism in Spain

- Spanish Maquis

References

Bibliography

Phase 1. 1930s–1980

- Bolloten, Burnett (1979). The Spanish Revolution. The Left and the Struggle for Power during the Civil War. University of North Carolina. ISBN 1842122037.

- Brenan, Gerald (1943). The Spanish Labyrinth: an account of the social and political background of the Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1993). ISBN 9780521398275. OCLC 38930004.

- Carr, Sir Raymond (1977). The Spanish Tragedy: The Civil War in Perspective. Phoenix Press (2001). ISBN 1-84212-203-7.

- Cox, Geoffrey (1937). The Defence of Madrid. London: Victor Gollancz. ISBN [[Special:BookSources/1 877372 3 84 (reprinted 2006 review)|1 877372 3 84 ([http://www.otago.ac.nz/press/booksauthors/2006/defence_madrid.html reprinted 2006] [http://www.listener.co.nz/issue/3481/artsbooks/7953/madrid_midnight_of_the_century.html;jsessionid=C8F5DD17257A84A136886D599DB9D5F9 review])]].

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); External link in|isbn= - Ibarruri, Dolores (1976). They Shall Not Pass: the Autobiography of La Pasionaria (translated from El Unico Camino by Dolores Ibarruri). New York: International Publishers. ISBN 0-7178-0468-2. OCLC 9369478.

- Jackson, Gabriel (1965). The Spanish Republic and the Civil War, 1931–1939. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00757-8. OCLC 185862219.

- Jellinek, Frank (1938). The Civil War in Spain. London: Victor Gollanz (Left Book Club).

- Low, Mary (1979 reissue of 1937). Red Spanish Notebook. San Francisco: City Lights Books (originally by Martin Secker & Warburg. ISBN 0-87286-132-5. OCLC 4832126.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|co-author=ignored (help) - Orwell, George (2000, first published in 1938). Homage to Catalonia. London: Penguin Books in association with Martin Secker & Warburg. ISBN 0-14-118305-5. OCLC 42954349.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - Payne, Stanley, G. (1970). The Spanish Revolution. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0297001248.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Puzzo, Dante Anthony (1962). Spain and the Great Powers, 1936–1941. Freeport, N.Y: Books for Libraries Press (originally Columbia University Press, N.Y.). ISBN 0-8369-6868-9. OCLC 308726.

- Rust, William (2003 Reprint of 1939 edition). Britons in Spain: A History of the British Battalion of the XV International Brigade. Pontypool, Wales (NP4 7AG): Warren and Pell.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: location (link) - Southworth, Herbert Rutledge (1963). El mito de la cruzada de Franco. Paris: Ruedo Ibérico. ISBN 8483465744.

- Taylor, F. Jay (1956, 1971). The United States and the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939. New York: Bookman Assocaites. ISBN ISBN 9780374978495.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Check date values in:|year=(help) - Thomas, Hugh (1961). The Spanish Civil War. London: Penguin (3rd edition, 2003). ISBN 0-14-101161-0. OCLC 248799351.

Phase 2. 1981–1999

- Anderson, James M. (2003). The Spanish Civil War: A History and Reference Guide. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-32274-0.

- Beevor, Antony (1982). The Spanish Civil War. London: Penguin (2001). ISBN 0-14-100148-8. OCLC 185343606.

- Howson, Gerald (1998). Arms for Spain. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-24177-1. OCLC 231874197.

- Koestler, Arthur (1983). Dialogue with death. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-34776-5. OCLC 16604744.

- Monteath, Peter (1994). The Spanish Civil War in literature, film, and art : an international Bibliography of secondary literature. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29262-0.

- Monteath, Peter (1994). Writing the Good Fight. Political Commitment in the International Literature of the Spanish Civil War. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-28766-X.

- Preston, Paul (1978). The Coming of the Spanish Civil War. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-23724-2. OCLC 185713276.

- Preston, Paul (1996). A Concise history of the Spanish Civil War. London: Fontana. ISBN 978-0006863731. OCLC 231702516.

- Wilson, Ann (1986). Images of the Civil War. London: Allen & Unwin.

Phase 3. 2000–2008

- Alpert, Michael (2004). A New International History of the Spanish Civil War. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-1171-1. OCLC 155897766.

- Beevor, Antony (2006). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936–1939. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0297-848325. OCLC 185382508.

- Doyle, Bob (2006). Brigadista – an Irishman's fight against fascism. Dublin: Currach Press. ISBN 1-85607-939-2. OCLC 71752897.

- Francis, Hywel (2006). Miners against Fascism: Wales and the Spanish Civil War. Pontypool, Wales (NP4 7AG): Warren and Pell.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Graham, Helen (2002). The Spanish republic at war, 1936–1939. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45932-X. OCLC 231983673.

- Greening, Edwin (2006). From Aberdare to Albacete: A Welsh International Brigader's Memoir of His Life. Pontypool, Wales (NP4 7AG): Warren and Pell.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Kowalsky, Daniel (2004). La Union Sovietica y la Guerra Civil Espanola. Barcelona: Critica. ISBN 84-8432-490-7. OCLC 255243139.

- O'Riordan, Michael (2005). The Connolly Column. Pontypool, Wales (NP4 7AG): Warren and Pell.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Othen, Christopher (2008). Franco's International Brigades: Foreign Volunteers and Fascist Dictators in the Spanish Civil War. London: Reportage Press.

- Payne, Stanley (2004). The Spanish Civil War, the Soviet Union, and Communism. New Haven; London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10068-X. OCLC 186010979.

- Prasad, Devi (2005). War is a Crime Against Humanity: The Story of War Resisters' International. London: War Resisters' International, wri-irg.org. ISBN 0-903517-20-5. OCLC 255207524.

- Preston, Paul (2007). The Spanish Civil War: Reaction, Revolution, and Revenge. New York: W. W. Norton and Company. ISBN 0393329879.

- Radosh, Ronald (2001). Spain betrayed: the Soviet Union in the Spanish Civil War. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08981-3. OCLC 186413320.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Wheeler, George (2003). To Make the People Smile Again: a Memoir of the Spanish Civil War. Newcastle upon Tyne: Zymurgy Publishing. ISBN 1-903506-07-7. OCLC 231998540.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Williams, Alun Menai (2004). From the Rhondda to the Ebro: The Story of a Young Life. Pontypool, Wales: Warren & Pell.

Notes

- ^ Thomas, p. 628

- ^ Thomas, p. 619

- ^ a b "Spanish judge opens case into Franco's atrocities". New York Times. 16 October 2008. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

- ^ The number of casualties is disputed; estimates generally suggest that between 500,000 and 1 million people were killed. Over the years, historians kept lowering the death figures and modern research concludes that 500,000 deaths is the correct figure. Thomas Barria-Norton, The Spanish Civil War (2001), pp. xviii & 899–901, inclusive.

- ^ a b Payne, Stanley Fascism in Spain, 1923-1977, pp. 200-203, 1999 Univ. of Wisconsin Press Cite error: The named reference "payne" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Martins, Herminio. "Portugal" in S.J. Woolf (ed). European Fascism, London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1968 pp. 322-3

quoted in Gallagher, Tom. Portugal: a twentieth-century interpretation. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1983 p.86Almost as soon as the civil war started, the Portuguese government more or less cast in its lot with the rebel forces and decided to support them by all means short of actual participation in the war.

- ^ http://pubs.socialistreviewindex.org.uk/isj62/newsinger.htm

- ^ a b Tierney, Dominic. FDR and the Spanish Civil War: Neutrality and Commitment in the Struggle That Divided America, pp. 67-8, Duke University Press, 2007

- ^ [1]

- ^ Orwell and the Spanish Revolution http://pubs.socialistreviewindex.org.uk/isj62/newsinger.htm

- ^ Blood of Spain P.38-39 Ronald Fraser ISBN 0-7126-6014-3

- ^ p.1 Mary Vincent, Catholicism in the Second spanish republic ISBN 0-19-820613-5

- ^ a b Payne, Stanley G. (1973). "A History of Spain and Portugal (Print Edition)". University of Wisconsin Press. Library of Iberian resources online: 646–47. Retrieved 15 May 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|vol=ignored (|volume=suggested) (help) - ^ Ronald Fraser, quoted in Blood of Spain, p.38

- ^ The Blood of Spain Ronald Fraser p.35, 37

- ^ A. Beevor, The Battle for Spain, p.23

- ^ Torres Gutiérrez, Alejandro ,Religious minorities in Spain: A new model of relationships? Center for Study on New Religions 2002

- ^ Burleigh, Michael, Sacred Causes: The Clash of Religion and Politics, From the Great War to the War on Terror, pp. 128-129 HarperCollins, 2007. Burleigh says the constitution "went much further than a legal separation of Church and state".

- ^ a b Anticlericalism Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ Dilectissima Nobis

- ^ Stepan, Alfred, Arguing Comparative Politics, p. 221, Oxford University Press

- ^ Martinez-Torron, Javier Freedom of religion in the case law of the Spanish Constitutional court Brigham Young University Law Review 2001

- ^ Payne, Stanley G. (1973). "A History of Spain and Portugal (Print Edition)". University of Wisconsin Press. Library of Iberian resources online: 632. Retrieved 30 May 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|vol=ignored (|volume=suggested) (help) - ^ The statistics on assassinations, destruction of religious buildings, etc. immediately before the start of the war come from The Last Crusade: Spain: 1936 by Warren Carroll (Christendom Press, 1998). He collected the numbers from Historia de la Persecución Religiosa en España (1936–1939) by Antonio Montero Moreno (Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos, 3rd edition, 1999).

- ^ a b c Payne, Stanley G. (1973). "A History of Spain and Portugal (Print Edition)". University of Wisconsin Press. Library of Iberian resources online: 642. Retrieved 30 May 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|vol=ignored (|volume=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "payne 642" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Payne, Stanley G. (1973). "A History of Spain and Portugal (Print Edition)". University of Wisconsin Press. Library of Iberian resources online: 643. Retrieved 30 May 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|vol=ignored (|volume=suggested) (help) - ^ Trotsky, Leon, "The Task in Spain", April 1936.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Preston, Paul, Franco and Azaña, Volume: 49 Issue: 5, May 1999, pp. 17–23 Cite error: The named reference "Preston" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Hugh Thomas, The Spanish Civil War, (1987), p. 8.

- ^ Zhooee, TIME Magazine, 20 July 1936 http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,771840,00.html

- ^ Bullón de Mendoza, Alfonso Calvo Sotelo: Vida y muerte (2004) Barcelona. Thomas, Hugh The Spanish Civil War (1961, rev. 2001) New York pp. 196–198 and p.309. Condés was a close personal friend of Castillo. His squad had originally sought to arrest Gil Robles as a reprisal for Castillo's murder, but Robles was not at home, so they went to the house of Calvo Sotelo. Thomas concluded that the intention of Condés was to arrest Calvo Sotelo and that Cuenca acted on his own initiative, although he acknowledges other sources that dispute this finding.

- ^ Beevor, Anthony. The Spanish Civil War. London: Penguin, 1982. p 49.

- ^ Alpert, Michael BBC History Magazine April 2002

- ^ Chomsky, Noam. "Objectivity and Liberal Scholarship (1969)" in Chomsky on Anarchism. AK Press, Oakland CA, 2005.

- ^ Beevor, The Battle for Spain, (2006) ("Chapter 21: The Propaganda War and the Intellectuals")

- ^ Antony Beevor, The Spanish Civil War, pp 32-3.

- ^ a b Payne, Stanley George The Spanish Civil War, the Soviet Union, and Communism p. 118 (2004 Yale University Press)

- ^ Antony Beevor, The Spanish Civil War, pp 42-43.

- ^ Antony Beevor, The Battle for Spain (2006), pp 30-33

- ^ Hugh Thomas, The Spanish Civil War, (1987), pp. 86–90.

- ^ Coverdale, John F., Uncommon faith: the early years of Opus Dei, 1928-1943, p. 148, Scepter 2002

- ^ Martyrs of Turon

- ^ Payne, Stanley Franco and Hitler: Spain, Germany, and World, p. 13, 2008 Yale Univ. Press

- ^ Rooney, Nicola "The role of the Catholic hierarchy in the rise to power of General Franco"

- ^ Business & Blood. Time, Monday, 19 April 1937

- ^ Peace and Pirates, TIME Magazine, 27 September 1937

- ^ Othen, Christopher. Franco's International Brigades (Reportage Press, 2008) p79

- ^ Othen, Christopher. Op cit p102

- ^ John R. Lampe and Mark Mazower, Ideologies and national identities, at p. 38

- ^ a b c d e Hitler and Spain Robert H Whealey

- ^ a b Thomas, Hugh. The spanish civil war. Penguin Books. London. 2001. p.944

- ^ The Spanish Civil War Antony Beevor

- ^ Antony Beevor, The Battle for Spain; The Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939 (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2006), pp 116, 133,143, 148, 174, 427.

- ^ Antony Beevor, The Battle for Spain (2006), pp 198

- ^ Antony Beevor, The Battle for Spain (2006), pp 116

- ^ Deletant, Dennis (1999). Communist terror in Romania: Gheorghiu-Dej and the Police State, 1948-1965. C. Hurst & Co. p. 20. ISBN 9781850653868.

- ^ Gregor Benton, Frank N. Pieke (1998). The Chinese in Europe. Macmillan. p. 215. ISBN 0333669134. Retrieved 2010-7-14.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ Academy of Sciences of the USSR, International Solidarity with the Spanish Republic, 1936-1939 (Moscow: Progress, 1974), 329-30

- ^ a b c d Arms for Spain Gerald Howson

- ^ Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain. Penguin Books. 2006. London. p.163

- ^ Graham, Helen. The Spanish Civil War. A very short introduction. Oxford University Press. New York. 2005. p.92

- ^ Thomas, Hugh. The Spanish Civil War. Penguin Books. London. 2003. p.944

- ^ "Nazi Germany and Francoist Spain" by Christian Leitz, pp. 127–150, Spain and the Great Powers in the 20th Century Routledge, New York, 1999, edited by Sebastian Balfour and Paul Preston.

- ^ Thomas, p. 820-821

- ^ Professor Hilton (27 October 2005). "Spain: Repression under Franco after the Civil War". Cgi.stanford.edu. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ^ Tremlett, Giles (1 December 2003). "Spain torn on tribute to victims of Franco". London: Guardian. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ^ Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain; The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Penguin Books. 2006. London. p.405

- ^ Caistor, Nick (28 February 2003). "Spanish Civil War fighters look back". BBC News. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ^ Film documentary on the website of the Cité nationale de l'histoire de l'immigration Template:Fr icon

- ^ "Spanish Civil War". Concise.britannica.com. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ^ Published: 12:01AM BST 11 Jun 2006 (11 June 2006). "A revelatory account of the Spanish civil war". London: Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Men of La Mancha". Rev. of Antony Beevor, The Battle for Spain. The Economist (22 June 2006).

- ^ Julius Ruiz, "Defending the Republic: The García Atadell Brigade in Madrid, 1936". Journal of Contemporary History 42.1 (2007):97.

- ^ César Vidal, Checas de Madrid: Las cárceles republicanas al descubierto. ISBN 978-84-9793-168-7

- ^ Decision of Juzgado Central de Instruccion No. 005, Audiencia Nacional, Madrid (16 October 2008)

- ^ a b Spain and Germany: Franco and Hitler, Paul Preston

- ^ Antony Beevor, The Battle for Spain; The Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939 (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2006), p.89.

- ^ Preston 2007, p. 121

- ^ Preston 2007, p. 120

- ^ Antony Beevor, The Battle for Spain; The Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939 (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2006), pp 88-89.

- ^ Franco and the Spanish Civil War By Filipe Ribeiro De Meneses

- ^ Franco and the Spanish Civil WarBy Filipe Ribeiro De Meneses

- ^ The Spanish Civil War: reaction, revolution and revenge By Paul Preston

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=gPQZsu0Ma0cC&pg=PA91&dq=Franco+executed+basque+priests&ei=Qr4xS83NAZqIkATAwNTPAQ&cd=4#v=onepage&q=Franco%20executed%20basque%20priests&f=false

- ^ http://www.iee-es.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=36&Itemid=1

- ^ [http://books.google.com/books?id=7OGih6t_0DgC&pg=PA47&dq=Basques+executed+franco&lr=&ei=DsAxS6WWE6OKkATdm_iuAQ&cd=14#v=onepage&q=Basques%20executed%20franco&f=false Spanish Best: The Fine Shotguns of Spain By Terry Wieland]

- ^ Ealham, Chris and Michael Richards, The Splintering of Spain, p. 80, 168, Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-521-82178-9, 9780521821780

- ^ "Shots of War: Photojournalism During the Spanish Civil War". Orpheus.ucsd.edu. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ^ [The Spanish Civil War: reaction, revolution and revenge By Paul Preston http://books.google.com/books?id=2vioVIdend4C&dq=Paul+Preston+spanish+civil+war&printsec=frontcover&source=bl&ots=jzdMK80Ak1&sig=GwMah-lm8lvneFpxsjFVyZ7NaNA&hl=en&ei=SMYxS-usHJHCsgOO_MjEBA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CAoQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=executed&f=false]

- ^ "Religious Persecution, Anticlerical Tradition and Revolution: On Atrocities against the Clergy during the Spanish Civil War" Journal of Contemporary History 33.3 (July 1998): 355.

- ^ Payne, Stanley G., A History of Spain and Portugal, Vol. 2, Ch. 26, (Print Edition: University of Wisconsin Press, 1973) (LIBRARY OF IBERIAN RESOURCES ONLINE p. 649.

- ^ Bowen, Wayne H., Spain During World War II, p. 222, University of Missouri Press 2006

- ^ a b Hugh Thomas, The Spanish Civil War, (1961) p. 176

- ^ Ian Gibson, "Paracuellos. Cómo fue". 1983, Plaza y Janés. Barcelona.

- ^ Anthony Beevor, Battle for Spain p. 161

- ^ Arnuad Imatz, "Espagne: la guerre des mémoires" (2009) 40 25-30, at 25

- ^ Noam Chomsky. "Objectivity and Liberal Scholarship". Question-everything.mahost.org. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ^ Arnaud Imatz, "La vraie mort de Garcia Lorca" 2009 40 NRH, 31-34, at p. 32-33).

- ^ Bennett, Scott, Radical Pacifism: The War Resisters League and Gandhian Nonviolence in America, 1915–1963, Syracuse NY, Syracuse University Press, 2003; Prasad, Devi, War is A Crime Against Humanity: The Story of War Resisters' International, London, WRI, 2005. Also see Hunter, Allan, White Corpsucles in Europe, Chicago, Willett, Clark & Co., 1939; and Brown, H. Runham, Spain: A Challenge to Pacifism, London, The Finsbury Press, 1937.

External links

Primary documents

- Magazines and journals published during the war, an online exhibit maintained by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- A collection of essays by Albert and Vera Weisbord with about a dozen essays written during and about the Spanish Civil War.

- Constitución de la República Española (1931)

- La Cucaracha, The Spanish Civil War Diary, a detailed chronicle of the events of the war

- Ronald Hilton, Spain, 1931–36, From Monarchy to Civil War, An Eyewitness Account

- Mary Low and Juan Breá: Red Spanish Book. A testimony by two surrealists and trotskytes

- Spanish Civil War and Revolution text archive in the libcom.org library

- The Nyon Agreement, 14 September 1937 – Agreement between 9 Powers for collective measures to be taken to suppress attacks by submarines against merchant vessels

Images and films

- Spain in Revolt 1, newsreel documentary (Video Stream)

- Spain in Revolt 2, newsreel documentary (Video Stream)

- Revistas y Guerra 1936–1939: La Guerra Civil Espanola y la Cultura Impresa online exhibition

- Imperial War Museum Collection of Spanish Civil War Posters hosted online by Visual Arts Data Service (VADS)

- Posters of the Spanish Civil War from UCSD's Southworth collection

- Civil War Documentaries made by the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo

- Spanish Civil War and Revolution image gallery – photographs and posters from the conflict

- Aircraft of the Spanish Civil War

- "spanish+civil+war") 64 "spanish civil war" objects in The European Library Harvest

Academics and governments

- A History of the Spanish Civil War, excerpted from a U.S. government country study.

- Columbia Historical Review Dutch Involvement in the Spanish Civil War

- "The Spanish Civil War – causes and legacy" on BBC Radio 4's In Our Time featuring Paul Preston, Helen Graham and Dr Mary Vincent

Other

- Spanish Civil War Original reports from The Times

- The Anarcho-Statists of Spain, a different view of the anarchists in the Spanish Civil War, George Mason University

- Spanish Civil War information, from Spartacus Educational

- American Jews in Spanish Civil War, by Martin Sugarman

- The Spanish Revolution, 1936–39 articles & links, from Anarchy Now!

- The Revolutionary Institutions: The Central Committee of Anti-Fascist Militias, by Juan García Oliver

- Warships of the Spanish Civil War

- ¡No Pasarán! Speech Dolores Ibárruri's famous rousing address for the defense of the Second Republic

- Spanish Civil War Forum

- New Zealand and the Spanish Civil War

- Spanish Civil War tours in Barcelona Covers themes such as Anarchism, George Orwell, the realities of daily life and bombing.