Talk:Shakespeare authorship question/Overlapping history

|

Note: This article is undergoing a rewrite, based on discussions here: Talk:Shakespeare authorship question#Merging procedure. Further discussions are being held at Talk:Shakespeare authorship question/sandbox. To make sandbox edits to the new article draft, please use this page: Talk:Shakespeare authorship question/sandbox draft. An alternate draft is located at Talk:Shakespeare authorship question/sandbox draft2. |

For the purposes of this article the term “Shakespeare” is taken to mean the poet and playwright who wrote the plays and poems in question; and the term “Shakespeare of Stratford” is taken to mean the William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon to whom authorship is credited.

The Shakespeare authorship question is the controversy about whether the works traditionally attributed to William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon were actually composed by another writer or group of writers.[1] The public debate dates back to the mid-19th century. It has attracted public attention and a thriving following, including some prominent public figures, but is dismissed by the great majority of academic Shakespeare scholars.[a][2] Those who question the attribution believe that "William Shakespeare" was a pen name used by the true author (or authors) to keep the writer's identity secret.[3] Of the numerous proposed candidates,[4] major nominees include Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, who currently attracts the most widespread support,[5] statesman Francis Bacon, dramatist Christopher Marlowe, and William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby, who—along with Oxford and Bacon—is often associated with various "group" theories. Supporters of the four main theories are called Oxfordians, Baconians, Marlovians, and Derbyites, respectively.[6]

Authorship doubters believe that mainstream Shakespeare biographers routinely violate orthodox methods and criteria,[7][8] and include inadmissible evidence in their histories of him.[9] They also claim that some mainstream scholars have ignored the subject in order to protect the economic gains that the Shakespeare publishing world has provided them.[10] Authorship doubters assert that the actor and businessman baptised as "Shakspere" of Stratford did not have the background necessary to create the body of work attributed to him, and that the personal attributes inferred from Shakespeare's poems and plays don't fit the known biography of him.[11] Anti-stratfordians also note the lack of any concrete evidence that Shakespeare of Stratford had the extensive education doubters claim is evident in Shakespeare's works. They question whether a commoner from a small 16th-century country town, with no recorded education or personal library, could become so highly expert in foreign languages, knowledge of courtly pastimes and politics, Greek and Latin mythology, law, and the latest discoveries in science, medicine and astronomy of the time. Doubters also focus on the relationship between internal evidence (the content of the plays and poems) and external evidence (biographical or historical data derived from other sources).[12]

The majority of academics specializing in Shakespearean studies, called "Stratfordians" by skeptics, generally ignore or dismiss these alternative theories, arguing they fail to comply with standard research methodology and lack supportive evidence from documents contemporary with Shakespeare.[improper synthesis?][citation needed] Mainstream scholars reject anti-Stratfordian arguments and say that authorship doubters discard the most direct testimony in favor of their own theories,[13] overstate Shakespeare's erudition,[14] and anachronistically mistake the times he lived in,[15] thereby rendering their method of identifying the author from the works unscholarly and unreliable.[improper synthesis?] Consequently, they have been slow to acknowledge the popular interest in the subject.[16] Support for William Shakespeare as author rests on two main pillars of evidence: testimony by his fellow actors, and by his fellow playwright Ben Jonson in the First Folio, and the inscription on Shakespeare's grave monument in Stratford.[17] Title pages, testimony by other contemporary poets and historians, and official records—the type of evidence used by literary historians that Stratfordians believe is lacking for any other alternative candidate—are also cited to support the mainstream view.[a][18] Despite this, interest in the authorship debate continues to grow, particularly among independent scholars, theatre professionals and a small minority of academics.[19]

Overview

Authorship doubters

An important principle for many of those who question Shakespeare’s authorship is the premise that most authors reveal themselves in their work, and that knowing some facts about the author's life helps readers to understand his writings.[20] With this principle in mind, authorship doubters find parallels in the fictional characters or events in the Shakespearean works and in the life experiences of their preferred candidate. The disjunction that skeptics perceive between the sparse facts known about Shakespeare of Stratford and the content of Shakespeare's works has raised doubts about whether the author and the Stratford Shakespeare are the same person.[21] This perceived dissonance, first expressed in the first half of the 19th century, has led authorship doubters to look for alternative explanations. This discordance between the bare biography traditionally provided and the evidence of superior education and travel in Shakespeare's work has been the major reason for doubts among such intellectuals as Mark Twain, Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, Charlie Chaplin, Walt Whitman, Tyrone Guthrie, John Gielgud and Supreme Court Justices Harry A. Blackmun, John Paul Stevens, and Sandra Day O'Connor, and the prominent Shakespearean actors Derek Jacobi and Mark Rylance[22] to publicly announce their doubts. In September 2007, the Shakespeare Authorship Coalition sponsored a "Declaration of Reasonable Doubt" to encourage new research into the question of Shakespeare's authorship, which has been signed by more than 1,700 people, including 295 academics.[23]

Although historically the academic community has accepted the traditional attribution, the authorship question has achieved some degree of acceptance as a legitimate research topic. Brunel University of London now offers a one-year MA program on the Shakespeare authorship question.[24] In 2007, the New York Times surveyed 265 Shakespeare professors on the topic. To the question "Do you think there is good reason to question whether William Shakespeare of Stratford is the principal author of the plays and poems in the canon?", 6% answered "yes" and an additional 11% responded "possible". When asked their opinion of the Shakespeare authorship question, 61% answered that it was a "A theory without convincing evidence" and 32% called the issue "A waste of time and classroom distraction", but when asked if they "mention the Shakespeare authorship question in your Shakespeare classes?", 72% answered "yes".[25]

Mainstream view

In contrast to the methods used by anti-Stratfordians to identify the poet and playwright William Shakespeare, orthodox scholars employ the same type of evidence used to identify other writers of the period: the historical record,[26] and maintain that the methods commonly used by anti-Stratfordians to identify alternate candidates—reading the work as autobiography, finding coded messages and cryptograms embedded in the works, and concocting conspiracy theories to explain the lack of evidence for anyone but Shakespeare—are unreliable and unscholarly, and explain why so many candidates, calculated as high as 56, have been nominated as the “true” author.[27][28] They say that the idea that Shakespeare revealed himself in his work is a Romantic notion of the 18th and 19th centuries and anachronistic to Elizabethan and Jacobean writers.[29] When William Wordsworth wrote that ‘Shakespeare unlocked his heart’ in the sonnets, Robert Browning replied, ‘If so, the less Shakespeare he!’[30]

The mainstream view, overwhelmingly supported by academic Shakespeareans, is that the author known as "Shakespeare" was the same William Shakespeare who was born in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1564, moved to London and became an actor and sharer (part-owner) of the Lord Chamberlain's Men acting company (later the King's Men) that owned the Globe Theatre and the Blackfriars Theatre in London and owned exclusive rights to produce Shakespeare's plays from 1594 on,[31] and who became entitled to use the honourific of gentleman when his father, John Shakespeare, was granted a coat of arms in 1596.

It states that William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon, Gentleman, is identified with the writer in London by at least four pieces of contemporary evidence that firmly link the two. (a) His will registers bequests to fellow actors and theatrical entrepreneurs, two of whom edited his works, namely (Heminges, Burbage, and Condell). (b) His village church monument bears an inscription linking him with Virgil and Socrates, and mentions he was a writer.[32] (c) Ben Jonson linked this 'Star of poets' with his home territory, in calling him the 'Swan of Avon', and (d) Leonard Digges, in verses prefixed to the First Folio, speaks of his 'Stratford Monument'.[33][34][35] Lastly, both the authorship doubter Paul H. Altrocchi and the mainstream biographer of de Vere, Alan Nelson, have uncovered, identified and interpreted an annotation in a book owned by a learned Warwickshire contemporary of Shakespeare's which for them proves that 'our William Shakespear' of Stratford was an important actor on the public stage.[b][36][37]

Although little biographical information exists about Shakespeare compared to later authors, mainstream scholars assert that more is known about him than about most other playwrights and actors of the period.[38] This lack of information is unsurprising, they say, given that in Elizabethan/Jacobean England the lives of commoners were not as well documented as those of the gentry and nobility, and that many—indeed the overwhelming majority—of Renaissance documents that existed have not survived until the present day.[39]. It has long been argued that anyone with a polished formal university education would never have made the many glaring mistakes, often of an elementary kind, which recur in Shakespeare's references to the classical world.[40]

Criticism of mainstream view

Lack of Literary paper trail

Some doubters, such as Charlton Ogburn, Jr., have asserted there is no direct evidence clearly identifying Shakespeare of Stratford as a playwright,[41] and that the majority of references to "William Shakespeare" by contemporaries refer to the author, but not necessarily the Stratford businessman.[42] Ogburn further stated his disbelief that Shakespeare of Stratford and the author shared the exact same name, noting that not one of Shakespeare of Stratford's six known signatures was actually spelled “Shakespeare” (i.e., Shaksp, Shakspe, Shaksper, Shakspere, Shakspere and Shakspeare).[43]

Independent researcher Diana Price, in Shakespeare's Unorthodox Biography, notes that for a professional author, Shakespeare of Stratford seems to have been entirely uninterested in protecting his work. Price explains that while he had a well-documented habit of going to court over relatively small sums, he never sued any of the publishers pirating his plays and sonnets, or took any legal action regarding their practice of attaching his name to the inferior output of others. Price also notes there is no evidence Shakespeare of Stratford was ever paid for writing, and his detailed will failed to mention any of Shakespeare's unpublished plays or poems or any of the source books Shakespeare was known to have read.[44][45] Anti-stratfordians also note that the only theatrical reference in Shakespeare of Stratford's will (gifts to fellow actors) were interlined—i.e., inserted between previously written lines—and thus are subject to doubt.

Anti-stratfordian Robert Brazil, in Shakespeare: The Authorship Controversy, notes that Shakespeare of Stratford's relatives and neighbors never mentioned that he was famous or a writer, nor are there any indications his heirs demanded or received payments for his supposed investments in the theatre or for any of the more than 16 masterwork plays unpublished at the time of his death.[46] Mark Twain, commenting on the subject, said, "Many poets die poor, but this is the only one in history that has died THIS poor; the others all left literary remains behind. Also a book. Maybe two."[47]

Ogburn, who examined the known evidence for and against the major nominees, notes that we know much more about the lives of other candidates (Bacon, Marlowe, Derby, Oxford) than we do about the life of the presumed traditional author William Shakespeare.[48] Regarding the lack of evidence surrounding Shakespeare, Professor Hugh Trevor-Roper noted “[d]uring his lifetime nobody claimed to know him. Not a single tribute was paid to him at his death. As far as the records go, he was uneducated, had no literary friends, possessed at his death no books, and could not write.”[49]

Alternate interpretations

Referring to the metaphor of the swan in "Swan of Avon", traditionally taken to be an epithet of great poets,[50] the de Vere Society claims that "the distinguishing characteristic of the swan, apart from its lifelong fidelity, was its silence - hence the name 'Mute Swan' for the commonest variety of this bird" and asserts that "William of Stratford was a mute participant in all this, it seems."[51] Also, Charles Wisner Barrell published extensive findings showing numerous ties between the Earl of Oxford, the river Avon, and the Avon Valley, where Oxford once owned an estate.[52]

Mark Anderson has suggested that "Greene's Groatsworth of Wit" could imply Shakespeare of Stratford was being given credit for the work of other writers, and that Davies' mention of "our English Terence" is a mixed reference, given that Roger Ascham, an Elizabethan scholar, knew that two of Terence's six plays were said to have been written by members of the Roman nobility.[53]

Public reaction to death

Doubters also question why, when Shakespeare of Stratford died, he was not publicly mourned.[54] As Mark Twain wrote, in Is Shakespeare Dead?, "When Shakespeare died in Stratford it was not an event. It made no more stir in England than the death of any other forgotten theater-actor would have made. Nobody came down from London; there were no lamenting poems, no eulogies, no national tears — there was merely silence, and nothing more. A striking contrast with what happened when Ben Jonson, and Francis Bacon, and Spenser, and Raleigh, and the other literary folk of Shakespeare’s time passed from life! No praiseful voice was lifted for the lost Bard of Avon; even Ben Jonson waited seven years before he lifted his."[47]

History of authorship doubts

Early doubts

During the life of William Shakespeare of Stratford and for more than 200 years after his death, no documentary evidence exists that anyone questioned the traditional attribution of the Shakespearean canon.[55] However, Anti-Stratfordian writers claim that several 16th and 17th century Elizabethan works hint that the Shakespearean canon was written by someone else. Independent researcher Diana Price speculates that an authorship debate existed in Elizabethan times, arguing that "all literary allusions [to Shakespeare] with some hint of personal information are ambiguous or cryptic,"[56] and maintains that these literary records contain veiled references to that debate, even if those doubts were not explicitly stated. Moreover, the first attempt to write a biography of Shakespeare did not appear until 1709, when Nicholas Rowe published a collection of Shakespeare's works and supplied a life which, according to the Encyclopædia Britannica, "although mostly composed of dubious tradition, remained the basis of accounts of Shakespeare until the early 19th Century." [57]

Like Diana Price, Charles Wisner Barrell, Roger Stritmatter, Brenda James, and W. D. Rubinstein all interpret Thomas Edward's L'Envoy to Narcissus (1595), in which Edwards uses allegorical nicknames in praising several Elizabethan poets. Following a verse about “Adon,” which they take to be an allusion to the mythical Adonis in Shakespeare's Venus and Adonis, Edwards's next verse is read as alluding to a real poet dressed "in purple robes", “whose power floweth far.” As purple is, among other things, a symbol of aristocracy, these researchers believe that Edwards is saying that Shakespeare was an aristocrat, Sir Henry Neville according to one view, the Earl of Oxford according to another.[58] Also, Walter Begley and Berthram G. Theobald claimed that Elizabethan satirists Joseph Hall and John Marston alluded to Francis Bacon as the true author of Venus and Adonis and Lucrece by using the sobriquet "Labeo" in a series of poems published in 1598.[59]

The first possible explicit allusions to doubts about Shakespearean authorship arose in certain 18th century satirical and allegorical works. In a passage in An Essay Against Too Much Reading (1728) by a "Captain" Golding, Shakespeare is described as "no Scholar, no Grammarian, no Historian, and in all probability cou'd not write English" and someone who uses an historian "when he wanted anything in his Way". The book also says that "instead of Reading, he [Shakespeare] stuck close to Writing and Study without Book".[60] Again, in The Life and Adventures of Common Sense: An Historical Allegory (1769) by Herbert Lawrence, the narrator, Common Sense, portrays Shakespeare, as a "Person belonging to the Play-House", a "Profligate in his Youth" who stole a commonplace book outlining the rules of dramatic writing from his father, Wit; a glass to penetrate into men's souls belonging to his crony, Genius; and a "Mask of curious Workmanship" that had the power of making spoken dialogue extremely pleasant and entertaining, belonging to his half-brother, Humour. Shakespeare is portrayed as using all of these to write his plays.[61] Thirdly, The Story of the Learned Pig, By an officer of the Royal Navy (1786) is a tale of a soul that has successively migrated from the body of Romulus into various animals, and is residing in a performing pig on exhibition. He recalls his history in other humans, one a chap called "Pimping Billy", who worked at the playhouse with Shakespeare and was the real author of the works.[62]

In 1932 Allardyce Nicoll published the discovery of a manuscript that appeared to establish that James Wilmot was the earliest proponent of Baconian theory.[63] The manuscript, "Some reflections on the life of William Shakespeare", was found among papers from the library of Sir Edwin Durning-Lawrence (1837–1914), a leading supporter of Bacon's candidacy, that had been donated to London University by his widow in 1929. Said to have been written up as a report to the "Ipswich Philosophic Society" in 1805 by one James Corton Crowell, it narrated Wilmot's supposed unsuccessful search for records relating to Shakespeare in Stratford on Avon and the surrounding area in 1780, which reportedly led him to conclude that Francis Bacon was the true author of Shakespeare's works. The later development of the Baconian theory during the 19th century owed nothing to Wilmot, but the authenticity of the manuscript was accepted after Nicholl’s publication. It has since been challenged by John Rollett and Daniel Wright, who could find no records for Cowell or the Ipswich Philosophic Society at that date. Wright says that the manuscript might have been forged to rejuvenate Bacon’s fading support and thereby to deflect the rise of Oxford’s proposed candidacy as the true author.[64]

The rise of bardolatry in the 17th and 18th centuries

Upon the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Charles II reopened the theatres, and two patent companies—the King's Company and the Duke's Company—were established. The profession of playwright had disappeared after 18 years of closed theatres, and so the existing theatrical repertoire—the works of Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, and Beaumont and Fletcher—which had been preserved by folio publication, were divided between the two companies and revived for the stage.[65] Sir William Davenant, head of the Duke’s Company and reputedly Shakespeare’s godson, was given the exclusive rights to perform 10 Shakespeare plays. As the director of the Duke's Company, Davenant was obliged to reform and modernize Shakespeare's plays before producing them, and the texts were "reformed" and "improved" for the stage.

During the 1660–1700 period, stage records suggest that Shakespeare, although always a major repertory author, was not as popular on the stage as were the plays of Beaumont and Fletcher, although in literary criticism he was acknowledged as an untaught genius even though did not follow the French neo-classical "rules" for the drama and the three classical unities of time, place, and action. John Dryden argued in his influential Essay of Dramatick Poesie (1668) for Shakespeare's artistic superiority to Ben Jonson, who does follow the classical unities, and as a result Jonson lands in a distant second place to "the incomparable Shakespeare", the follower of nature and the great realist of human character.

In the 18th century, Shakespeare dominated the London stage, and after the Licensing Act of 1737, one fourth of the plays performed were by Shakespeare. The plays continued to be heavily cut and adapted, becoming vehicles for star actors such as Spranger Barry and David Garrick, a key figure in Shakespeare's theatrical renaissance, whose Drury Lane theatre was the centre of the Shakespeare mania which swept the nation and promoted Shakespeare as the national playwright.[66] At Garrick's spectacular 1769 Shakespeare Jubilee in Stratford-upon-Avon, he unveiled a statue of Shakespeare and read out a poem culminating with the words "'tis he, 'tis he, / The God of our idolatry".[67]

In contrast to playscripts, which diverged more and more from their originals, the publication of texts developed in the opposite direction. With the invention of textual criticism and an emphasis on fidelity to Shakespeare's original words, Shakespeare criticism and the publication of texts increasingly spoke to readers, rather than to theatre audiences, and Shakespeare's status as a "great writer" shifted. Two strands of Shakespearean print culture emerged: bourgeois popular editions and scholarly critical editions.[68] Nahum Tate and Nathaniel Lee prepared editions and introduced modern scene divisions in the late 17th century, and Nicholas Rowe's edition of 1709 is considered the first scholarly edition of the plays. It was followed by many good 18th-century editions, crowned by Edmund Malone's landmark Variorum Edition, which was published posthumously in 1821.

Dryden's sentiments about Shakespeare's matchless genius were echoed without a break by unstinting praise from writers throughout the 18th century. Shakespeare was described as a genius who needed no learning, was deeply original, and unique in creating realistic and individual characters (see Timeline of Shakespeare criticism). The phenomenon continued during the Romantic era, when Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Keats, William Hazlitt, and others all described Shakespeare as a transcendent genius. By the beginning of the 19th century Bardolatry was in full swing and Shakespeare was universally celebrated as an unschooled supreme genius and had been raised to the status of a secular god and many Victorian writers treated Shakespeare's works as a secular equivalent to the Bible.[69] "That King Shakespeare," the essayist Thomas Carlyle wrote in 1840, "does not he shine, in crowned sovereignty, over us all, as the noblest, gentlest, yet strongest of rallying signs; indestructible".[70]

Debate in the 19th century

Uneasiness about the difference between Shakespeare's godlike reputation and the humdrum facts of his biography, earlier expressed in allegorical or satirical works, began to emerge in the 19th century. In 1811 Samuel Taylor Coleridge expressed his amazement that "works of such character should have proceeded from a man whose life was like that attributed to Shakespeare."[citation needed] In 1850, Ralph Waldo Emerson expressed the underlying question in the air about Shakespeare with his confession, "The Egyptian [i.e. mysterious] verdict of the Shakspeare Societies comes to mind; that he was a jovial actor and manager. I can not marry this fact to his verse."[72][73] That the perceived dissonance between the man and his works was a consequence of the deification of Shakespeare was theorized by J.M. Robertson, who speculated that "It is very doubtful whether the Baconian theory would ever have been framed had not the idolatrous Shakespeareans set up a visionary figure of the Master."[74]

At the same time scholars were increasingly becoming aware that many plays were products of several authors' work, and that now-lost plays may have served as models for Shakespeare's published work, such as, for example, the ur-Hamlet, an earlier version of Shakespeare's play of that name.[c][75] In Benjamin Disraeli's novel Venetia (1837) the character Lord Cadurcis, modelled on Byron[76], suggests that Shakespeare may not have written "half of the plays attributed to him", or even one "whole play" but rather that he was "an inspired adaptor for the theatres".[77] A similar view was expressed by an American lawyer and writer, Col. Joseph C. Hart, who in 1848 published The Romance of Yachting, which for the first time stated explicitly and unequivocally in print that Shakespeare did not write the works bearing his name. Hart claimed that Shakespeare was a "mere factotum of the theatre", a "vulgar and unlettered man" hired to add obscene jokes to the plays of other writers.[78] Hart does not suggest that there was any conspiracy, merely that evidence of the real authors's identities had been lost when the plays were published. Hart asserts that Shakespeare had been "dead for one hundred years and utterly forgotten" when old playscripts formerly owned by him were discovered and published under his name by Nicholas Rowe and Thomas Betterton. He speculates that only The Merry Wives of Windsor was Shakespeare's own work and that Ben Jonson probably wrote Hamlet.[75] In 1852 an essay by Dr. R. W. Jamieson, published anonymously in Chambers's Edinburgh Journal also suggested that Shakespeare owned the playscripts, but had employed an unknown poor poet to write them.[79]

In 1853, with help from Emerson, Delia Bacon, an American teacher and writer, travelled to Britain to research her belief that Shakespeare's works were written to communicate the advanced political and philosophical ideas of Francis Bacon (no relation). She discussed her theories with British scholars and writers. In 1856 she wrote an article in Putnam's Monthly in which she insisted that Shakespeare of Stratford would not have been capable of writing such plays, and that they must have expressed the ideas of an unspecified great thinker. Later in 1856 William Henry Smith, in a privately-circulated letter, expressed his view that Francis Bacon himself had written the works, and the following year he published the letter as a booklet. Smith claimed to have been unaware of Delia Bacon's essay and to have held his opinion for nearly 20 years.[80] In 1857 Bacon expanded her ideas in her book, The Philosophy of the Plays of Shakespeare Unfolded.[81] She argued that Shakespeare's plays were written by a secretive group of playwrights led by Sir Walter Raleigh and inspired by the philosophical genius of Sir Francis Bacon. Both writers gained immediate and wide public attention, including the first attempt at refutation by the publication of George Henry Townsend's William Shakespeare Not an Impostor (1857) in England, and the public Shakespeare authorship controversy was born.[82]

Later writers such as Ignatius Donnelly portrayed Francis Bacon as the sole author. The Baconian movement attracted much attention and caught the public imagination for many years, mostly in America.[83][84] Ignatius Donnelly's claim to have discovered ciphers in the works of Shakespeare revealing Bacon as a "concealed poet" were later discredited by William and Elizabeth Friedman, expert code-breakers, in their book The Shakespeareen Ciphers Examined.[85]

The American poet Walt Whitman declared himself agnostic on the issue and refrained from endorsing an alternative candidacy. Voicing his skepticism to Horace Traubel, Whitman remarked, "I go with you fellows when you say no to Shaksper: that's about as far as I have got. As to Bacon, well, we'll see, we'll see."[86]

20th century candidates

Starting in 1908, Sir George Greenwood engaged in a series of well-publicised debates with Shakespearean biographer Sir Sidney Lee and author J. M. Robertson. Throughout his numerous books on the authorship question, Greenwood limited himself to arguing against the traditional attribution, without supporting any alternative candidate.[87]

In 1918, Professor Abel Lefranc, a renowned authority on French and English literature, after a 35-year study of Shakespeare, published the first volume of Sous le masque de "William Shakespeare". Based on biographical evidence found in the plays and poems, he put forward William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby as the author.[88] Many scholars were impressed by Lefranc's arguments, and a large international body of literature resulted.[89]

In 1920, an English school-teacher, John Thomas Looney, published Shakespeare Identified, proposing a new candidate for the authorship in Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. This theory gained many notable advocates, including Sigmund Freud. In 1922, Looney joined Greenwood in founding The Shakespeare Fellowship, an international organization dedicated to promote discussion and debate on the authorship question.

By the early 20th century, the public had tired of cryptogram-hunting, and the Bacon movement faded. The result was increased interest in Stanley and Oxford as alternative candidates.[90]

In 1923, Archie Webster wrote the first serious essay on the candidacy of playwright Christopher Marlowe, who was first suggested by Wilbur E. Ziegler in the foreword to his 1895 novel, It Was Marlowe: A Story of the Secret of Three Centuries.[91] Marlowe continues to attract supporters, and in 2001, the Australian documentary film maker Michael Rubbo released the TV film Much Ado About Something, which explores the theory in some detail. It has played a significant part in bringing the Marlovian theory to the attention of the greater public.

Since the publication of Charlton Ogburn's The Mysterious William Shakespeare: the Myth and the Reality in 1984, the Oxfordian theory, boosted in part by the advocacy of several Supreme Court justices and high-profile theatre professionals, has become the most popular alternative authorship theory.[92]

Pseudonymous or secret authorship in Renaissance England

Archer Taylor and Frederic J. Mosher identified the 16th and 17th centuries as the "golden age" of pseudonymous authorship and maintain that during this period “almost every writer used a pseudonym at some time during his career.”[93] Anti-Stratfordians have argued that the authorship question is a manifestation of early modern censorship, which caused many authors to hide their identities in one way or another.[94] The connection between the authorship question and the history of censorship, while implied in much earlier scholarship, is made explicit in an article published in the Oxfordian journal, Brief Chronicles, which argues that the need for a pseudonym can readily be explained on the basis of a prevailing "stigma of print."[95]

At least two of the proposed candidates for authorship, the Earls of Oxford [96] and Derby[97] were known to be playwrights, even though no extant work survives under their own name.

Diana Price has analyzed several examples of Elizabethan commentary on anonymous or pseudonymous publication by persons of high social status. According to her, "there are two historical prototypes for this type of authorship fraud, that is, attributing a written work to a real person who was not the real author". Both are Roman in origin:

- Bathyllus took credit for verses written by Virgil, and then accepted a reward for them. In 1591, a pamphleteer (Robert Greene) described an Elizabethan Batillus, who put his name to verses written by certain poets who, because of "their calling and gravity" did not want to publish under their own names. This Batillus was accused of "under-hand brokery." [98]

- A second prototype is the classical comedian Terence, whom the Elizabethan pedagogue and classicist Roger Ascham noted was credited with having written two plays that some Latin sources thought were written by a member of the Roman nobility and a plebian.[99].

An example of Elizabethan authorities raising the issue is provided by the case of Sir John Hayward:

- In 1599 he published The First Part of the Life and Raigne of King Henrie IV dedicated to Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex. Queen Elizabeth and her advisers disliked the tone of the book and its dedication, and on July 11, Hayward was interrogated before the Privy Council, which was seeking "proof positive of the Earl's [sc. Essex's] long-standing design against the government" in writing a preface to Hayward's work.[100] The Queen "argued that Hayward was pretending to be the author in order to shield 'some more mischievous' person, and that he should be racked so that he might disclose the truth".[101]

"Shake-Speare" as a pseudonym

Anti-Stratfordians have alleged a variety of reasons for supposing that the name "Shakespeare" would have made a symbolically apt pseudonym. According to Anderson, among others, the name alludes to the patron goddess of art, literature and statecraft, Pallas Athena, who sprang from the forehead of Zeus, shaking a spear.[102] Both Ogburn and Anderson have argued that the hyphen which often appeared in the name "Shake-speare" indicated the use of a pseudonym.[103] Examples of oft-hyphenated names include Tom Tell-truth, Martin Mar-prelate (who pamphleteered against church "prelates"),[104] and Cuthbert Curry-knave, who "curried" his "knavish" enemies.[105]

Ogburn noted that of the "32 editions of Shakespeare's plays published before the First Folio of 1623 in which the author was named at all, the name was hyphenated in fifteen – almost half." Further, it was hyphenated by John Davies in the famous poem which references the poet as "Our English Terence," by fellow playwright John Webster, and by the epigrammatist of 1639 who wrote, "Shake-speare, we must be silent in thy praise…." Ogburn noted that the hyphen was only used by other writers or publishers, and not by the poet himself (he did not use it in his personal dedications of his two long narrative poems), and concludes that the hyphenation was not by chance, but instead followed a pattern.[103] Another recent article in the Oxfordian online journal Brief Chronicles applies numerical analysis of Francis Meres's Palladis Tamia ("The Servant of Pallas Athena") to argue that although on the surface he seems to be attributing a dozen plays to Shakespeare of Stratford, he may be read as esoterically identifying Oxford as the real author.[106]

Irvin Matus responds that the claim of hyphenation as a marker of a pseudonym is unknown outside of anti-Stratfordian literature, and that no scholar of Elizabethan literature or punctuation has written about hyphens as such.[107] In addition, of the 15 examples of Shakespeare's name being hyphenated in the works, 13 of those were from different editions of only three plays (Richard II, Richard III, and 1 Henry IV) all published by the same printer, Andrew Wise, and the man who took over Wise's business in 1603, Matthew Law. Orthodox scholars also point out that it was common[citation needed] for proper names of real people to be hyphenated in print in Elizabethan times. Matus notes that Elizabethan poet and clergyman Charles Fitzgeoffrey’s name often appeared in print as "Charles Fitz-Geffry;" Protestant martyr Sir John Oldcastle, as “Old-castle;” London Lord Mayor Sir Thomas Campbell, “Camp-bell;” printer Edward Allde, “All-de;” and printer Robert Waldegrave, “Walde-grave.”[108]

"Shakspere" vs. "Shakespeare"

Anti-Stratfordians conventionally refer to the man from Stratford as "Shakspere" (the name recorded at his baptism) or "Shaksper" to distinguish him from the author "Shakespeare" or "Shake-speare" (the spellings that appear most often on the publications). Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, a noted Oxfordian, has stated that most references to the man from Stratford in legal documents usually spell the first syllable of his name with only four letters, "Shak-" or sometimes "Shag-" or "Shax-", whereas the dramatist's name is more consistently printed as "Shake".[109]

Stratfordians reject this convention, pointing out that there was no standardised spelling in Elizabethan England, and Shakespeare of Stratford's name was spelled in many different ways, including "Shakspere", "Shaxper", "Shagspere" and "Shakespeare";[110] that examples anti-Stratfordians give for Shakespeare of Stratford's name are all handwritten and not printed; that anti-Stratfordians are factually incorrect in that most of those examples were spelled either Shakespeare, Shakespere, or Shakespear;[111] and that handwritten examples of the author's name exhibit the same amount of variation.[112] Stratfordian David Kathman also argues that the anti-Stratfordian characterization of the name—"Shakspere" or "Shakspur"—incorrectly characterizes the contemporary spelling of Shakespeare's name and introduces prejudicial negative implications of the Stratford man in the minds of modern readers.[113]

Debate points used by anti-Stratfordians

Doubts about Shakespeare of Stratford

Literary paper trails

Diana Price’s Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography: New Evidence of an Authorship Problem approaches the authorship question by going back to the historical documents and testimony that underpin Shakespeare’s biography. Price believes that centuries of biographers have suspended their standards and criteria to weave inadmissible evidence into their narratives. She offers new analyses of the evidence and then reconstructs Shakespeare of Stratford’s professional life.

Literary biographies, i.e., lives of writers, are based on evidence left behind during the writer’s lifetime, such as manuscripts, letters, diaries, personal papers, receipts, etc. Price calls these "literary paper trails" - the documents that allow biographers to reconstruct the life of their subject as a writer. Price acknowledges that Shakespeare of Stratford did leave behind a considerable amount of evidence, but asserts that none of it traces his alleged career as a playwright and poet. In his case, the first document in the historical record that “proves” he was a writer was created after he died.[114] Price notes that historians routinely distinguish between contemporaneous and posthumous evidence, and they don’t give posthumous evidence equal weight - but Shakespeare’s biographers do.

The central chapter on Literary Paper Trails, and an associated appendix chart, compare the evidence of two dozen other writers with that of Shakespeare of Stratford’s.[115] The criteria are simple and routinely employed by historians and biographers of other subjects. Evidence that is personal, contemporaneous, and supports one statement, “he was a writer by vocation or profession,” qualifies for inclusion in the comparative chart.[116] Price sorted the evidence into numerous categories, which were then collapsed into 9 categories, with a 10th one created to serve as an all-purpose catch-all to ensure that no qualifying paper trail was excluded.

Each of these two dozen Elizabethan and Jacobean writers left behind a variety of records shedding light on their writing activities. For example, historians know how much some of them got paid for writing a poem or a play, or how much a patron rewarded them for their literary effort. Some left behind letters referring to their plays or poems. A few of them left behind handwritten manuscripts or books with handwritten annotations.

Shakespeare of Stratford left behind over seventy historical records, and over half of these records shed light on his professional activities. Price notes, however, that every one of these documents concerns non-literary careers – those of theatrical shareholder, actor, real estate investor, grain trader, money-lender, and entrepreneur. But he left behind not one literary paper trail that proves he wrote for a living. In the genre of literary biography for Elizabethan and Jacobean writers, Price concludes that this deficiency of evidence is unique.

Shakespeare's education

Authorship doubters believe that the author of Shakespeare's works manifest a higher education, displaying knowledge of contemporary science, medicine, astronomy, rhetoric, music, and foreign languages. They further assert that there is no evidence that Shakespeare of Stratford ever attained such an education.

In addition, the writer of the Shakespeare canon exhibited a very extensive vocabulary, variously calculated, according to different criteria, as ranging between 17,500 to 29,066 words.[117] "The plays of Shakespeare," said Henry Stratford Caldecott in an 1895 Johannesburg lecture, "are so stupendous a monument of learning and genius that, as time passes and they are probed and searched and analysed by successive generations of scholars and critics of all nations, they seem to loom higher and grander, and their hidden beauties and treasured wisdom to be more and more inexhaustible; and so people have come to ask themselves not only, 'Is it humanly possible for William Shakespeare, the country lad from Stratford-on-Avon, to have written them?', but whether it was possible for any one man, whoever he may have been, to have done so."[118] As for the role of genius in acquiring knowledge, 18th century critic Samuel Johnson said "Nature gives no man knowledge, and when images are collected by study and experience, can only assist in combining or applying them. Shakespeare, however [he may have been] favoured by nature, could impart only what he had learned." [119]

The Stratfordian position[who?] maintains that Shakespeare of Stratford would have received the kind of education available to the son of a Stratford alderman at the local grammar school and at the parish church, including a comfortable mastery of the Bible, Latin, grammar and rhetoric. The former was run by a number of Oxford graduates, Simon Hunt, Thomas Jenkins and John Cottom, and the latter by Henry Heicroft, a fellow at St John's College, Cambridge.[120] Though there is no evidence that he attended a university, a degree was not a prerequisite for a Renaissance dramatist, and mainstream scholars have long assumed Shakespeare of Stratford to be largely self-educated, with such authorities as Jonathan Bate devoting much space in biographies to the issue.[121] A commonly cited parallel is his fellow dramatist Ben Jonson, a man whose origins were humbler than those of the Stratford man, and who rose to become court poet. Like Shakespeare of Stratford, Jonson never completed and perhaps never attended university, and yet he became a man of great learning (later being granted an honorary degree from both Oxford and Cambridge).

Authorship doubters note that as the records of the school's pupils have not survived, Shakespeare of Stratford's attendance cannot be proven,[122] and that no one who ever taught or attended The King's School ever claimed to have been his teacher or classmate, and the school or schools Shakespeare of Stratford might have attended are a matter of speculation as there are no existing admission records for him at any grammar school, university or college. Doubters also point out that there is clearer evidence for Jonson's formal education and self-education than for Shakespeare of Stratford's. Several hundred books owned by Ben Jonson have been found signed and annotated by him[123] but no book has ever been found which proved to have been owned or borrowed by Shakespeare of Stratford. It is known, moreover, that Jonson had access to a substantial library with which to supplement his education.[124] Charlton Ogburn Jr., reports that Ben Jonson's stepfather, a master bricklayer, "provided his stepson with the foundations of a good education." Young Ben went first to a private school in St. Martin's Lane and later at Westminster studied under one of the foremost Elizabethan scholars, William Camden, of whom he wrote: "Camden, most revered head, to whom I owe/ All that I am in arts, all that I know." [125] Ogburn devotes several pages to discussing the poor quality of education at English grammar schools [126] Ogburn specifically rejects Professor T. M. Baldwin's Small Latin and Lesse Greeke for, first of all, misreading the Jonson quotation (leaving out the qualifying "Though thou hadst" and Jonson's subsequent comparison of Shakespeare to the greatest of Classical authors)[127] and secondly, for citing a speculation as if it were fact: "William Shakspere should have learned from someone, at present unguessable, to read English, and about the age of seven, in the course of 1571, have entered the grammar school." [128].

Possible evidence of Shakespeare of Stratford's self-education includes the fact that certain sources for his plays were sold at the shop of the printer Richard Field, a fellow Stratford native.[129] Some contemporary references have been interpreted to say that Shakespeare's works have not always been considered to require an unusual amount of education: Ben Jonson's tribute to Shakespeare in the 1623 First Folio (arguably) states that his plays were great despite his having only "small Latin and less Greek".[130] And it has been argued by Dr Richard Farmer, that a great deal of the classical learning he displays is derived from one text, Ovid's Metamorphoses, which was a set text in many schools at the time.[131]

Anti-Stratfordians such as Mark Anderson, however, believe this explanation does not counter the argument that the author also required a knowledge of foreign languages, modern sciences, warfare, law, statesmanship, hunting, natural philosophy, history, and aristocratic sports such as tennis and falconry.[132]

Shakespeare's life experience

Anti-Stratfordians believe that a provincial glovemaker's son who resided in Stratford until early adulthood would be unlikely to have written plays that deal so personally with the activities, travel and lives of the nobility. The view is summarised by Charles Chaplin: "In the work of greatest geniuses, humble beginnings will reveal themselves somewhere, but one cannot trace the slightest sign of them in Shakespeare. . . . Whoever wrote them (the plays) had an aristocratic attitude."[133] Orthodox scholars respond that the glamorous world of the aristocracy was a popular setting for plays in this period. They add that numerous English Renaissance playwrights, including Christopher Marlowe, John Webster, Ben Jonson, Thomas Dekker and others wrote about the nobility despite their own humble origins.

Authorship doubters stress that the plays show a detailed understanding of politics, the law and foreign languages that would have been impossible to attain without an aristocratic or university upbringing. Orthodox scholars respond that Shakespeare was an upwardly mobile man: his company regularly performed at court and he thus had ample opportunity to observe courtly life.

In The Genius of Shakespeare, Jonathan Bate argues that the class argument is reversible: the plays contain details of lower-class life about which aristocrats might have little knowledge. Many of Shakespeare's most vivid characters are lower class or associate with this milieu, such as Falstaff, Nick Bottom, Autolycus, Sir Toby Belch, etc.[134] Anti-Stratfordians have responded that while the author's depiction of nobility was highly personal and multi-faceted, his treatment of commoners was quite different. Tom Bethell, in Atlantic Monthly, commented "The author displays little sympathy for the class of upwardly mobile strivers of which Shakspere (of Stratford) was a preeminent member. Shakespeare celebrates the faithful servant, but regards commoners as either humorous when seen individually or alarming in mobs".[135]

He also shows a detailed knowledge of the uses of the hides and innards of various animals which would be more likely in someone of relatively humble background.[136]

It has also been noted[by whom?] that in the 17th century, Shakespeare was not thought of as an expert on the court, but as a "child of nature" who "Warble[d] his native wood-notes wild" as John Milton put it in his poem L'Allegro. Contemporary playwright Francis Beaumont thought this not a disadvantage. He wrote to Jonson: "I would let slip ... scholarship and from all learning keep these lines as clear as Shakespeare's best are ... to show how far a mortal man may go by the dim light of Nature".[137] John Dryden wrote in 1668 that playwrights Beaumont and Fletcher "understood and imitated the conversation of Gentlemen much better" than Shakespeare, and in 1673 wrote of Elizabethan playwrights in general that "I cannot find that any of them had been conversant in courts, except Ben Jonson."

Anti-Stratfordians note that it took 12 years for Ben Jonson (whose lower-class background was similar to that of the Stratfordian Shakespeare) to obtain noble patronage from Prince Henry for his commentary The Masque of Queens (1609). They thus express doubt that the true author could have quickly obtained the Earl of Southampton's patronage for one of his first published works, the long poem Venus and Adonis (1593).

Shakespeare's literacy

Anti-Stratfordians such as Charleton Ogburn question the degree of literacy of Shakespeare of Stratford. No letter written by Shakespeare is known to exist, and they maintain it would only be logical for a man of Shakespeare's writing ability to compose numerous letters, and given the man's supposed fame they find it unbelievable that not one letter, or record of a letter, exists.[138] Doubters point out that many dramatists of the time wrote a fluent hand, (dramatists such as Jonson, Marlowe, and Lyly), [citation needed] and that no equivalent samples of playscripts are available as evidence for the literacy of Shakespeare of Stratford. Ogburn also notes that his known signatures offer no proof of writing abilities.[139] Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens has stated that "the evidence of Shakespeare's handwriting that we do have ... consists of six signatures on legal documents, each suggesting that merely writing his name was a difficult task and, remarkably, that his name was Shaksper rather than Shakespeare."[109]

While “many dramatists of the time wrote a fluent hand”, many didn't, and when compared to some other dramatists of the era, the alleged wretchedness of Shakespeare's hand wasn't unique. The hand of Thomas Heywood, one of the most prolific playwrights of the era, is described as “abominable” and “the least legible” of all extant dramatists’ hands of the era.[140] Other notable writers of the era who had what today would be considered illegible hands include Philip Massinger, described as “awkward and untidy”,[141] Sir Thomas Overbury, “barely decipherable scratches”,[142] Michael Drayton, “untidy and loosely written”,[143] Thomas Dekker, “scratchy”,[144] Thomas Nashe, “scrappiness . . . numerous blots . . . generally legible . . .ill-defined”,[145] and Robert Southwell, “fairly legible”.[146]

Mainstream scholars who specialize in studying handwriting of the past, known as palaeographers, say that the handwriting of Shakespeare's time is difficult for modern readers.[147] Shakespeare's signatures are written in secretary hand, a style of handwriting that vanished by 1700,[148] and which can be “confusing and often downright misleading” to those unfamiliar with it.[149] Sir Edward Maunde Thompson, who studied and wrote extensively about Shakespeare’s handwriting, said that “the style of the poet's hand, as shown by his signatures, was that of the ordinary scrivener or copyist of the time (that is, in the native English script) ”, and that "there can be no question of the dramatist's ability to write a fluent hand".[150]

Despite Thompson’s opinion and his use of the signatures to identify Shakespeare’s co-authorship in the anonymous play Sir Thomas More, even some Stratfordians disagree with his assessment because of the appearance of Shakespeare’s surviving signatures, as Irvin Matus admits.[151] British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper notes that "It is true, six of his signatures have been found, all spelt differently; but they are so ill-formed that some graphologists suppose the hand to have been guided.”[138] And Jane Cox, of the Public Record Office (now The National Archives), suggests that clerks wrote the signatures instead of Shakespeare,[152] a position Matus outlines as a possibility but stops short of endorsing.[153]

Other arguments against Shakespeare of Stratford's literacy are the apparent illiteracy of his parents and family. According to authorship researcher Diana Price, Shakespeare of Stratford's wife Anne and daughter Judith appear to have been illiterate, suggesting he did not teach them to write.[citation needed]

Mainstream scholars have responded that most middle-class women in the 17th century were illiterate, and statistical evidence compiled by David Cressy indicates that a large percentage (as high as 90%) of these women may not have had enough education to sign their own names.[154]

Shakespeare's will

Anti-stratfordians note that Shakespeare of Stratford's will is long and explicit, bequeathing the possessions of a successful middle class businessman but making no mention of personal papers or books (which were expensive items at the time) of any kind, nor any mention of poems or of the 18 plays that remained unpublished at the time of his death, nor any reference to the valuable shares in the Globe Theatre that the Stratford man reportedly owned.[citation needed] This contrasts with Sir Francis Bacon, whose two wills refer to work that he wished to be published posthumously.[155] Anti-Stratfordians find it unusual that the Stratford man did not wish his family to profit from his unpublished work or was unconcerned about leaving them to posterity, and find it improbable that he would have submitted all the manuscripts to the King's Men, the playing company of which he was a shareholder, prior to his death.[citation needed]

Stratfordians point out that the complete inventory of Shakespeare's possessions, mentioned at the bottom as being attached (Inventarium exhibitum), has been lost, and that is where any books or manuscripts would have been mentioned. In addition, not one of Shakespeare's contemporary playwrights mentioned play manuscripts in their wills,[156] and for good reason: plays were owned by the playing companies, who sold the publishing rights at their discretion, so all of Shakespeare's plays were not his to dispose of, being owned by the King's Men.[157] It is not known whether William Shakespeare still owned the shares in the Globe Theatre at his death, but three other major share holders besides Shakespeare who were positively known to hold shares when they died—Richard Burbage, Augustine Phillips, and Henry Condell—also didn't mention Globe shares in their wills.[158]

Shakespeare's funerary monument

Shakespeare's grave monument in Stratford, built within a decade of his death, currently features an effigy of him with a pen in hand, suggestive of a writer, with an attached inscribed plaque praising his abilities as a writer. But anti-Stratfordians assert that the monument was clearly altered after its installation, as the earliest printed image of the monument in Sir William Dugdale's Antiquities of Warwickshire, published in 1656, merely portrays a man holding a grain sack.[160] The monument is portrayed similarly in Nicholas Rowe’s 1709 edition of Shakespeare’s works. The earliest record of the pen (which evidently broke from the hand in the late eighteenth century and is now represented by a real goose quill) dates from an engraving of the memorial made by George Vertue in 1723 and published in Alexander Pope's 1725 edition of Shakespeare's plays.[159]

Dugdale drew heraldic arms and monuments competently, but not figures and faces, his biographers say.[161] Dugdale identified Shakespeare as a poet on his drawing and published the monument inscription praising Shakespeare's literary abilities. Anti-Stratfordian researcher Diana Price examined Dugdale's original sketch drawn in 1634 and determined that Dugdale initially drew a flatter cushion in pencil, later inking the drawing, probably off-site.[citation needed] The engraver, Wenceslaus Hollar, freely improvised the engraving more than 20 years later, adding bulges suggesting a sack. She concluded that the monument had not been altered and that all subsequent similar images were derived from Hollar, not from the monument itself.[162]

When the effigy and cushion, made of a solid piece of Cotswold limestone, was removed from its niche in 1973, Sam Schoenbaum examined it and rendered an opinion that the monument was substantially as it was when first erected, with the hands resting on paper and writing-cushion, saying that "no amount of restoration can have transformed the monument of Dugdale's engraving into the effigy in Stratford church."[163]

Oxfordian Richard Kennedy has proposed that the monument was originally built to honour John Shakespeare, William’s father, who was described by Rowe as a “considerable” (although illegal) wool dealer, and that the effigy was later changed to fit the writer.[164] Kennedy’s theory gained the support of orthodox scholars Sir Brian Vickers and Peter Beal.[165] According to Vickers, "[W]ell-documented records of recurrent decay and the need for extensive repair work . . . make it impossible that the present bust is the same as the one that was in place in the 1620s."[166]

Marlovian Peter Farey contends that he has found a riddle embedded in the monument’s inscription, which when combined with a cryptic reference on the tombstone, identifies Marlowe as the true author.[167]

Comments by contemporaries

Comments on Shakespeare by Elizabethan literary figures have been read by anti-Stratfordians as expressions of doubt about his authorship:

Ben Jonson had a contradictory relationship with Shakespeare. He regarded him as a friend – saying "I loved the man"[168] – and wrote tributes to him in the First Folio. However, Jonson also wrote that Shakespeare was too wordy: Commenting on the Players' commendation of Shakespeare for never blotting out a line, Jonson wrote "would he had blotted a thousand" and that "he flowed with that facility that sometimes it was necessary he should be stopped."[168] In the same work, he scoffs at a line Shakespeare wrote "in the person of Caesar": "Caesar never did wrong but with just cause", which Jonson calls "ridiculous,"[169] and indeed the text as preserved in the First Folio carries a different line: "Know, Caesar doth not wrong, nor without cause / Will he be satisfied" (3.1). Jonson ridiculed the line again in his play The Staple of News, without directly referring to Shakespeare. Some anti-Stratfordians interpret these comments as expressions of doubt about Shakespeare's ability to have written the plays.[170]

In Robert Greene's posthumous publication Greene's Groatsworth of Wit (1592; published, and possibly written, by fellow dramatist Henry Chettle) a dramatist labeled "Shake-scene" is vilified as "an upstart Crowe beautified with our feathers", along with a quotation from Henry VI, Part 3. The orthodox view is that Greene is criticizing the relatively unsophisticated Shakespeare of Stratford for invading the domain of the university-educated playwright Greene.[171] Some anti-Stratfordians claim that Greene is in fact doubting Shakespeare's authorship.[172] In Greene's earlier work Mirror of Modesty (1584), the dedication mentions "Ezops Crowe, which deckt hir selfe with others feathers" referring to Aesop's fable (The Crow, the Eagle, and the Feathers) satirizing people who boast they have something they do not actually have.

In John Marston's satirical poem The Scourge of Villainy (1598), Marston rails against the upper classes being "polluted" by sexual interactions with the lower classes. Seasoning his piece with sexual metaphors, he then asks:

- Shall broking pandars sucke Nobilitie?

- Soyling fayre stems with foule impuritie?

- Nay, shall a trencher slaue extenuate,

- Some Lucrece rape? And straight magnificate

- Lewd Jovian Lust? Whilst my satyrick vaine

- Shall muzzled be, not daring out to straine

- His tearing paw? No gloomy Juvenall,

- Though to thy fortunes I disastrous fall.

There is a tradition that the satirist Juvenal became "gloomy" after being exiled by Domitian for having lampooned an actor that the emperor was in love with.[173] Anti-stratfordians believe Marston's piece can be interpreted as being directed at an actor, and questioning whether such a lower class "trencher slave" is extenuating (making light of) "some Lucrece rape" (The Rape of Lucrece), with Shakespeare depicted as a "broking pandar" (procurer), implicitly questioning his credentials to "sucke Nobilitie", (attract the Earl of Southampton's patronage of him).[citation needed]

Publications

The First Folio

The First Folio (1623), the first collected edition of Shakespeare's plays, has generated considerable debate among authorship doubters, who have raised questions about the various dedications to "Shake-speare", as well as the famous Folio frontispiece. The engraving itself is usually attributed to Martin Droeshout the Younger.

Born in 1601, Droeshout was only 10 years old when Shakespeare of Stratford retired, and only 14 years old when he died. Seven additional years passed before the Folio's publication. These circumstances, authorship doubters believe, make it unlikely that Droeshout actually knew the playwright personally. Because of this, authorship researchers have questioned the circumstances behind the work, including Jonson's assertion that the engraving was "true to life".

Charlton Ogburn, author of The Mysterious William Shakespeare (1984), also noted that the curved line running from the ear to the chin makes the face appear more of a "mask" than a true representation of an actual person,[174] though art historians see nothing unusual in these features.[175] Stratfordians respond to the claim that Droeshout was too young to have known Shakespeare by noting that the assumption has long been that he worked from a sketch, which was normal practice for engravers.

Geographical knowledge in the plays

Most anti-Stratfordians believe that a well-travelled man wrote the plays, as many of them are set in European countries and show great attention to local details. Orthodox scholars respond that numerous plays of this period by other playwrights are set in foreign locations and Shakespeare is thus entirely conventional in this regard. In addition, in many cases Shakespeare did not invent the setting, but borrowed it from the source he was using for the plot.

Even outside of the authorship question, there has been debate about the extent of geographical knowledge displayed by Shakespeare. Some scholars argue that there is very little topographical information in the texts (nowhere in Othello or the Merchant of Venice are the many canals of Venice mentioned). They also note apparent mistakes: for example, Shakespeare refers to Bohemia as having a coastline in The Winter's Tale (the region is landlocked), refers to Verona and Milan as seaports in The Two Gentlemen of Verona (the cities are inland), in All's Well That Ends Well he suggests that a journey from Paris to Northern Spain would pass through Italy, and in Timon of Athens he believes that there are substantial tides in the Mediterranean Sea, and that they take place once instead of twice a day.[176]

Answers to these objections have been made by other scholars (both orthodox and anti-Stratfordian). One explanation given for Bohemia having a coastline is that the same geographical mistake was already present in Shakespeare's source, Robert Greene's Pandosto, and the play merely reproduced it.[177] Another is the author's awareness that the kingdom of Bohemia in the 13th century under Ottokar II stretched to the Adriatic and that in Shakespeare's time (since 1558) the King of Bohemia also was Holy Roman Emperor and ruled over the Adriatic coast neighboring the Venetian Republic.[178]

It has been noted that The Merchant of Venice demonstrates detailed knowledge of the city, including the obscure facts that the Duke held two votes in the City Council, and that a dish of baked doves was a time-honoured gift in northern Italy.[102] Shakespeare also used the local word, "traghetto", for the Venetian mode of transport (printed as 'traject' in the published texts[179]). Anti-Stratfordians suggest that the above information would most likely be obtained from first-hand experience of the regions under discussion and conclude that the author of the plays could have been a diplomat, aristocrat or politician.

Mainstream scholars assert that Shakespeare's plays contain several colloquial names for flora and fauna that are unique to Warwickshire, where Stratford-upon-Avon is located, for example 'love in idleness' in A Midsummer Night's Dream.[180] These names may suggest that a Warwickshire native might have written the plays. Warwickshire characters from the villages of Burtonheath and Wincot, both near Stratford, are identifiable in The Taming of the Shrew.[181] Oxfordian researchers respond that the Earl of Oxford owned a manor house in Bilton, Warwickshire which, records show, he leased out in 1574 and sold in 1581.[182]

The poems as evidence

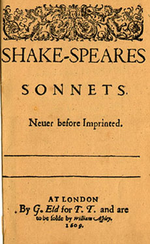

Ever since their recovery in 1709 after being out of print for over half a century, the Shakespearean Sonnets have provided a major stimulus promoting inquiry into the author's biography and giving rise in critical ways to the authorship question itself. What man—or what kind of a man—wrote these extraordinary poems?

Many scholars interpret the sonnets as personal expressions of emotions and experiences: the English romantic poet Wordsworth, for example, said that with the sonnets "Shakespeare unlocked his heart."[183] Others, such as Sidney Lee and Samuel Schoenbaum, have argued that they are academic exercises having no biographical significance, or dramatizations presented in the voice of a persona who is no more real than the characters "Shylock and Hamlet".[184][185]

Those who consider the sonnets a key to the author's personality have attempted to identify the "Fair Youth," the "Dark Lady," and the "Rival Poet." Although there is no consensus about how these characters fit into the life of Shakespeare of Stratford,[186] by far the most popular view among traditional scholars is that the Fair Youth is Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton (1573–1624), to whom Venus and Adonis and Rape of Lucrece had previously been dedicated.

Most Anti-Stratfordians read the sonnets as expressions of genuine biographical significance, and argue that these "mystery characters" can be identified as figures in the lives of their proposed candidates, although they do not always agree on the identities of the implicated persons.[187][188] Since Looney's Shakespeare Identified was published in 1920, Oxfordians generally concur with the identification of the Fair Youth as Wriothesley and, indeed, regard the identification as a major point in favor of their theory. They point out that Wriothesley, during the early 1590s when the seventeen "procreation" sonnets were written, was being urged by his guardian, Lord Burghley, to marry Lady Elizabeth Vere, the eldest daughter of Edward de Vere.[189] However, Charlton Ogburn points out that the "procreation" sonnets do not advocate any particular woman for the youth to marry. They simply exhort him to marry, beget a son, and thus perpetuate the beauty of his own youth through reproduction.[190]

Oxfordians such as Charlton Ogburn also cite Sonnet 76 (among others) as evidence of the author's implication that the plays and poems were written under a pseudonym ("noted weed" in this sonnet means a "well-recognized garment," as in "widows' weeds"):

- Why write I still all one, ever the same,

- And keep invention in a noted weed,

- That every word doth almost tell my name,

- Showing their birth, and where they did proceed?

The poet complains in Sonnet 76 of "art made tongue-tied by authority"; this suggests his frustration over censorship of some kind. And in Sonnet 111, Shakespeare laments that "my name receives a brand/ and almost thence my nature is subdue'd/ by what it works in, like the dyer's hand."

Date of playwright's death

Shake-speare's Sonnets

Oxfordian supporters believe they can identify evidence that the actual playwright was dead by 1609, the year Shake-speare's Sonnets, appeared with "our ever-living Poet"[191] on the dedication page, words typically used[192] to eulogize someone who has died, yet has become immortal.[193] Shakespeare himself used the phrase in this context in Henry VI, part 1 describing the dead Henry V as "[t]hat ever living man of memory" (4.3.51). And in 1665, Richard Brathwait used the exact same terminology referring to the deceased poet Jeffrey Chaucer, "A comment upon the two tales of our ancient, renovvned, and ever-living poet Sr. Jeffray Chavcer, Knight."[194]

Joseph Sobran, in Alias Shakespeare (1997), says that the finality of the title, Shake-speares Sonnets, suggests a complete body of work, with no more sonnets expected from the author, and notes that "the standard explanation is that the Sonnets were printed without (Shakespeare's) permission or cooperation".[195] In fact, there is no record that Shakespeare of Stratford, who was not beyond suing his neighbors over paltry sums, ever objected or sought recompense for the publication.[196] In addition, it is argued that some sonnets may be taken to suggest their author was older than the Stratford Shakespeare (#16, #30, #31, #62, #65, #73, #107, #138),[197] and possibly approaching death.[198]

The academic mainstream[citation needed] responds that the term “ever-living” does not necessarily imply that the person being described was dead. Anti-Stratfordian researcher, John Rollett, found an example of the epithet being applied to Queen Elizabeth, some eight years before her death,[199] and Donald Foster has pointed out that the phrase “ever-living” appears most frequently in Renaissance texts as a conventional epithet for eternal God.[200]

Foster also asserts that the term "begetter” was frequently used to mean "author" in Renaissance book dedications.[201] Thus, Jonathan Bate, leaving out the initials, translates the largely formulaic dedication in modern English as “Thomas Thorpe, the well-wishing publisher of the following sonnets, takes the opportunity upon publishing them to wish their only author all happiness and that eternity promised by our ever living poet.”[202] Fosters claim, and the Bate translation, however, do not represent the mainstream belief, espoused by noted Shakespearean scholar Sydney Lee, that "In Elizabethan English there was no irregularity in the use of 'begetter' in its primary sense of 'getter' or 'procurer'". Lee compiled numerous examples of the word used in this way and notes that doubt of this definition is "barely justifiable".[203]

Some modern Shakespearen specialists, such as Katherine Duncan-Jones, believe the sonnets were published with Shakespeare’s full authorization,[204] this assertion, however, stands in contrast to the more general believe noted by Lee, that "The corrupt state of the text Thorpe's edition of 1609 fully confirms that the enterprise lacked authority,...the character of the numerous misreadings leaves little doubt that Thorpe had no means of access to the authors MS."[205]

1604-1616 period

Oxfordian researchers believe certain documents imply the actual playwright had stopped writing, or was dead by 1604, the year continuous publication of new Shakespeare plays "mysteriously stopped",[206] and various writers and scholars have asserted that The Winter's Tale,[207] The Tempest, Henry VIII,[208] and Antony and Cleopatra,[209] so-called "later plays", were composed no later than 1604.[210] Also, since Shakespeare of Stratford lived until 1616, anti-Stratfordians question why, if he were the author, he did not eulogize Queen Elizabeth at her death in 1603 or Henry, Prince of Wales, at his in 1612.[211] Nor did Shakespeare memorialize the coronation of James I in 1604, the marriage of Princess Elizabeth in 1612, and the investiture of Prince Charles as the new Prince of Wales in 1613.[212]

Orthodox scholars note that as well as being a dramatist, Shakespeare was a narrative poet and a sonneteer, not an occasional poet, and that his neglect of Queen Elizabeth’s death was hardly unique. In one of the few such eulogies, Englandes Mourning Garment, Henry Chettle reproaches Shakespeare as well as other contemporary poets for their neglect of the queen’s death, including Chapman, Jonson, Drayton, Dekker, and Marston, all of whom were alive at the time.[213]

An edition of The Passionate Pilgrim expanded with an additional nine poems written by Thomas Heywood with Shakespeare’s name on the title-page was published by William Jaggard in 1612. Heywood protested this piracy in his Apology for Actors (1612), adding that the author was "much offended with M. Jaggard (that altogether unknown to him) presumed to make so bold with his name." That Heywood stated with certainty that the author was unaware of the deception, and that Jaggard removed Shakespeare’s name from unsold copies even though Heywood didn't explicitly name him, indicates that Shakespeare was the offended author who was very much alive at the time.[214]

Candidates and their champions

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford

The most popular present-day candidate is Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford.[215] [216][217][218] The Oxfordian theory was first proposed by J. Thomas Looney in 1920, whose work persuaded, among others, Sigmund Freud[219], Orson Welles and Marjorie Bowen. Oxford rapidly overtook Bacon as the most widely accepted candidate among anti-Stratfordians and by the late 1930s had achieved prominent public visibility as the most popular alternative candidate.[220]

Oxfordians point to the acclaim of Oxford's contemporaries regarding his talent as a poet and a playwright, his reputation as a concealed poet, and his personal connections to London theatre and the contemporary playwrights of Shakespeare's day. They also note his long term relationships with Queen Elizabeth I and the Earl of Southampton, his knowledge of Court life, his extensive education, his academic and cultural achievements, and his wide-ranging travels through France and Italy to what would later become the locations of many of Shakespeare's plays.

The case for Oxford's authorship is also based on perceived similarities between Oxford's biography and events in Shakespeare's plays, sonnets and longer poems; parallels of language, idiom, and thought between Oxford's personal letters and the Shakespearean canon;[221] and underlined passages in Oxford's personal bible, which Oxfordians believe correspond to quotations in Shakespeare's plays.[222] Confronting the issue of Oxford's death in 1604, Oxfordian researchers cite examples they say imply the writer known as "Shakespeare" or "Shake-speare" died before 1609, and point to 1604 as the year regular publication of "new" or "augmented" Shakespeare plays stopped.

Sir Francis Bacon

In 1856, William Henry Smith put forth the claim that the author of Shakespeare's plays was Sir Francis Bacon, a major scientist, philosopher, courtier, diplomat, essayist, historian and successful politician, who served as Solicitor General (1607), Attorney General (1613) and Lord Chancellor (1618). Smith was followed by Delia Bacon in her book The Philosophy of the Plays of Shakespeare Unfolded(1857), in which she maintained that Shakespeare's work was in fact written by a group of writers, including Francis Bacon, Sir Walter Raleigh and Edmund Spenser, who collaborated for the purpose of anonymously inculcating a philosophic system that she professed to discover beneath the superficial text of the plays.

Supporters of Bacon draw attention to similarities between a great number of specific phrases and aphorisms from the plays and those written down by Bacon in his wastebook, the Promus,[223]. In a letter Bacon refers to "concealed poets"[224], which his supporters take as a confession. They also point to Bacon's comment that play-acting was used by the ancients "as a means of educating men's minds to virtue,"[225] and say that since he outlined both a scientific and moral philosophy in his Advancement of Learning, but only his scientific philosophy was known to have been published during his lifetime (Novum Organum 1620), that he left his moral philosophy to posterity in the Shakespeare plays (e.g. the nature of good government exemplified by Prince Hal in Henry IV, Part 2).

Christopher Marlowe

A case for the gifted young playwright and poet Christopher Marlowe was made as early as 1895 in Wilbur Gleason Zeigler's foreword to his novel, It Was Marlowe: A Story of the Secret of Three Centuries.[226] Although only two months older than Shakespeare, Marlowe is recognized by scholars as the primary influence on Shakespeare's work, the "master" to Shakespeare's "apprentice". Unlike any other authorship candidate, Marlowe is believed to have been a brilliant poet and dramatist, the true originator of "Shakespearean" blank verse drama, and the only candidate to have actually demonstrated the potential to achieve the literary heights that Shakespeare did,[227] had he not been killed at the age of 29, as the historical record shows.