Haplogroup I-M253

| Haplogroup I1 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Possible time of origin | 4,000 to 6,000 BC |

| Possible place of origin | Scandinavia |

| Ancestor | I |

| Defining mutations | M253, M307, P30, P40 |

| Highest frequencies | People of Northern Europe (Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, Finnish, Sami, Estonian, Latvian, German, Dutch, English, Scottish, Irish), French |

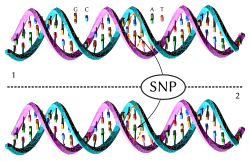

In human genetics, Haplogroup I1 is a Y chromosome haplogroup occurring at greatest frequency in Scandinavia, associated with the mutations identified as M253, M307, P30, and P40. These are known as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). It is a subclade of Haplogroup I. Before a reclassification in 2008,[1] the group was known as Haplogroup I1a.[2] Some individuals and organizations continue to use the I1a designation.

The group displays a very clear frequency gradient, with a peak of approximately 40 percent among the populations of western Finland and more than 50 percent in the province of Satakunta,[3] around 35 percent in southern Norway, southwestern Sweden especially on the island of Gotland, and Denmark, with rapidly decreasing frequencies toward the edges of the historically Germanic sphere of influence.

Origins

Ken Nordtvedt of Montana State University believes that I1 is a more recent group, probably emerging after the Last Glacial MaximumLGM.[4] Other researchers including Peter A. Underhill of the Human Population Genetics Laboratory at Stanford University have since supported this hypothesis in independent research.[5][6]

The study of I1, which some had argued was largely ignored by the genetic testing industry in favor of "mega-haplogroups" like R, is in flux. Revisions and updates to previous thinking, primarily published in academic journals, is constant, yet slow, showing an evolution in thought and scientific evidence.[7]

The most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of I1 lived from 4,000 to 6,000 years ago somewhere in the far northern part of Europe, perhaps Denmark, according to Nordtvedt. His descendants are primarily found among the Germanic populations of northern Europe and the bordering Uralic and Celtic populations, although even in traditionally German demographics I1 is overshadowed by the more prevalent Haplogroup R.

When SNPs are unknown or untested and when short tandem repeat (STR) results show eight allele repeats at DYS455, haplogroup I1 can be predicted correctly with a very high rate of accuracy, 99.3 to 99.8 percent, according to Whit Athey and Vince Vizachero.[8][9] This is almost exclusive to and ubiquitous in the I1 haplogroup, with very few having seven, nine, or another number. Furthermore, DYS462 divides I1 geographically. Nordtvedt considers 12 allele repeats to be more likely Anglo-Saxon and on the southern fringes of the I1 map, while 13 signifies more northerly, Nordic origins. Nordtvedt has repeatedly argued that, at least for I1,[10] SNP testing is generally not as beneficial as expanded STR results.

Subclades

Note: The systematic subclade names have changed several times in recent years, and are likely to change again, as new markers which clarify the sequence of branchings of the tree are discovered.

- I1 (M253,[11] M307,[12] L75, L80, L81, L118, L121, L123, L125, M450, M307.1/P203.1, P30, P40, S62, S63, S64, S65, S66, S107, S108, S109, S110, S111[13]) formerly I1a

- I1*

- I1a (M21) formerly I1a2

- I1b (M227) formerly I1a1, I1a4

- I1b*

- I1b1 (M72) formerly I1a1a, I1a3

- I1c (P259) formerly I1d

- I1d (L22/S142)

- I1d*

- I1d1 (P109) formerly I1c

- I1e (S79)

- L338

Distribution

This article or section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (August 2008) |

Outside Scandinavia, distribution of Haplogroup I1 is closely correlated with Haplogroup I2a1, but among Scandinavians including both Germanic and Uralic peoples of the region nearly all of the Haplogroup I chromosomes are I1. It is common near the southern Baltic and North Sea coasts, although successively decreasing the further south geographically. The Migration Period or "wandering of peoples" may explain the dispersion of I1 into areas beyond northern Europe.

Britain

The traditional view of British and Irish prehistory was that several waves of migration had resulted in widespread, if not total, population displacement. After the Last Glacial Maximum the region was first repopulated by Paleolithic hunter gatherers. During the Neolithic period, with the spread of farming, this population was supposedly replaced by the farmers. Later immigrations were thought to have accompanied the transitions to bronze and iron-working, known respectively as the Bronze and Iron Ages. The introduction of iron was particularly significant because archaeologists had associated it with the Hallstatt and La Tène cultures. These came to be associated by early archaeologists with the so-called Celtic culture, which was seemingly widespread on the continent. A later migration, that of the Anglo-Saxons, was also claimed to have led to total population replacement, but genetic evidence suggests otherwise. In his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Bede claimed that the Angles came to Britain en masse as an entire nation leaving no one behind in their homeland Angeln.[14] Other population movements (though not total displacements) recorded during historical times include those of the Danish and Norwegian Vikings, Danes in the east of England (especially the Danelaw) and Norwegians in the Shetland and Orkney Isles, Western Isles and Ireland.

The replacement model has been under sustained attack since the 1960s, with researchers asserting a much greater continuity than previously known or acknowledged. British archaeologist Simon James attributes the idea of large-scale mass migration to the assumption of primitivism about earlier inhabitants, assuming that cultural changes, such as nomadic hunter-gathering to farming, stone-working to metalworking, and bronze-working to iron-working, required newcomers introducing materials and techniques to the indigenous population, rather than them learning through trade or other methods.

Francis Pryor has stated that he "can't see any evidence for bona fide mass migrations after the Neolithic."[15] Historian Malcolm Todd writes, "It is much more likely that a large proportion of the British population remained in place and was progressively dominated by a Germanic aristocracy, in some cases marrying into it and leaving Celtic names in the, admittedly very dubious, early lists of Anglo-Saxon dynasties. But how we identify the surviving Britons in areas of predominantly Anglo-Saxon settlement, either archaeologically or linguistically, is still one of the deepest problems of early English history."[16] Although the idea of mass human migrations into Great Britain and Ireland is now a relatively minor point of view amongst British and Irish archaeologists, there is still a perception outside of the archaeological community that an "Anglo-Saxon" mass migration (especially) occurred, and that this forms a fundamental division between English "Anglo-Saxon" populations in Great Britain and non-English "Celtic" populations.

In 2002 a paper titled "Y Chromosome Evidence for Anglo-Saxon Mass Migration" was published by the Centre for Genetic Anthropology at the University College London in cooperation with Vrije Universiteit and the University of California, Davis claiming direct genetic evidence for population differences between the English and Welsh populations and proposed a model for mass invasion of eastern Great Britain from northern Germany and Denmark.[17] The authors assumed that populations with large proportions of haplogroup I originated from northern Germany or southern Scandinavia, particularly Denmark, and that their ancestors had migrated across the North Sea with Anglo-Saxon migrations and Danish Vikings.

In her book Origins of the English Catherine Hills criticized these conclusions, arguing that a biased sampling strategy flawed the study, especially since testing was limited only to regions in England where Danes were known to have settled during the Danelaw, which is archaeologically distinct. In the paper the main claim by the researchers was

that an Anglo-Saxon immigration event affecting 50–100% of the Central English male gene pool at that time is required. We note, however, that our data do not allow us to distinguish an event that simply added to the indigenous Central English male gene pool from one where indigenous males were displaced elsewhere or one where indigenous males were reduced in number … This study shows that the Welsh border was more of a genetic barrier to Anglo-Saxon Y chromosome gene flow than the North Sea … These results indicate that a political boundary can be more important than a geophysical one in population genetic structuring.

The paper was widely publicized in the media, especially in the United Kingdom, but reporting was often misleading and inaccurate. For example, the BBC claimed that the "English and Welsh are races apart" and asserted "that between 50% and 100% of the indigenous population of what was to become England was wiped out" though this was not a claim of the paper.[18] The conclusion for evidence of mass Anglo-Saxon migration, and that east English samples were more similar to Frisian samples than to Welsh samples, did not support the archaeological orthodoxy of modern times. A year later, in 2003, the paper "A Y Chromosome Census of the British Isles" was published by Capelli et al..[19] This paper, which sampled Great Britain and Ireland on a grid, found a much smaller difference between Welsh and English samples, and was much more characterised by isolation by distance, with a gradual decrease in Haplogroup I frequency moving westwards in southern Great Britain. It also found North German and Danish samples were not more similar to east English samples than Welsh samples.

Oxford archaeologist David Miles has argued that 80 percent of the genetic makeup of native Britons probably comes from "just a few thousand" nomadic tribesmen who arrived 12,000 years ago, at the end of the Ice Age. This suggests later waves of immigration may have been too small to have significantly affected the genetics of the pre-existing population.[20]

Traditionally, areas with a majority Angle influence included the Kingdoms of Northumbria (Nord Angelnen, Nordimbria Anglorum), East Anglia (Ost Angelnen) and Mercia (Mittlere Angelnen) while the Saxon areas were the Kingdoms of Sussex (Suth Seaxe), Essex (Est Seaxna), and Wessex (West Seaxna).[21] The Kingdom of Kent was considered a place of another Germanic tribe, the Jutes. Stephen Oppenheimer suggested that the Anglo-Saxon invasions actually had been predominantly Anglian.[22]

Meanwhile, Bryan Sykes has said that the Anglo-Saxons made a substantial contribution to the genetic makeup of England, but probably less than 20 percent of the total, even in southern England, where raids and settlements were supposedly commonplace. His conclusions, on Britain at least, mirror those of other researchers including Siiri Rootsi and Nordtvedt.[23] A report on the Saxons who were part of the Germanic settlement of Britain during and after the fifth century was issued by University College London in July 2006, with a wide-ranging estimate for the total number of settlers varying between 10,000 and 200,000.[24]

The Vikings, both Danes and Norwegians, also made a substantial contribution after the Angles, Saxons and Jutes, Sykes said, with concentrations in central, northern, and eastern England, territories of the ancient Danelaw. Sykes said he found evidence of a very heavy Viking contribution in the Orkney and Shetland Islands, near 40 percent. Mitochondrial DNA as well as Y DNA of northern Germanic origin was discovered at substantial rates in all of these areas, showing that the Vikings engaged in large-scale settlement, Sykes explained. However, Nordtvedt has said that separating I1 haplotypes into Viking and non-Viking groups has been impossible thus far.

Evidence of Norman genetic influence in England was extremely small – about two percent according to Sykes, discounting the idea that William the Conqueror, his troops and any settlers disrupted and displaced previous cultures. Some notable British historians and Anglophiles including J. R. R. Tolkien assumed that the Norman invasion of AD 1066 greatly affected the society of the time and that little survived from the "original" Britons. This worldview permeates Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings and other writings, though he focuses on Germanic folktales and legends rather than the Celtic in creating a replacement mythology, albeit fictional. In England, from the fifth to seventh centuries, the Anglo-Saxons soon developed their own variety as well.

The study of languages and place names provides more supporting evidence. For example, Old English emerged from the Anglo-Frisian dialects brought to Britain by Germanic settlers and perhaps Roman soldiers. The convergence of varying languages lends credence to a diverse genetic pool. Initially, the English language began as a diverse group of dialects reflecting the varied backgrounds of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. One of these dialects, Late West Saxon, eventually dominated.

Then two waves of invaders brought new influences. The first was by language speakers of the Scandinavian branch, known as North Germanic. They conquered and colonized parts of Britain in the eighth and ninth centuries. The second was the Normans in the eleventh century, who spoke Old Norman and ultimately developed an English variety called Anglo-Norman. These two invasions caused English to become linguistically "mixed" to some degree. English developed into a "borrowing" language of great flexibility with a large vocabulary.

In England the Viking Age began dramatically on June 8, 793, when Norsemen destroyed the abbey at Lindisfarne, plundering and murdering indiscriminately. An incident four years earlier, in which three Viking ships were beached in Portland Bay, perhaps on a trading expedition, created some tension, but Lindisfarne was different. The devastation of Northumbria's Holy Island shocked many, including the royal Courts of Europe. More than any other single event, the attack on Lindisfarne cast a shadow on the perception of the Vikings for the next twelve centuries.

France

This article possibly contains original research. (August 2008) |

Genetic remnants remain in northern France, indicating a small influx of I1 men, likely during Viking raids and subsequent settlement.[25] Subtle increases in I1 haplotypes indicate a modest contribution, perhaps from a combination of the Frankish migration during the last days of the Roman Empire and later Viking incursions. Nordtvedt subscribes to this concept.[26]

The Franks, for whom France (literally "Land of the Franks") is named, were a Germanic tribe first identified in the third century as an ethnic group living north and east of the Lower Rhine. They founded one of the Germanic monarchies which replaced the Western Roman Empire from the fifth century. The Frankish state consolidated its hold over large parts of Western Europe by the end of the eighth century. The Carolingian Empire and its successor states were Frankish. French nobility were often descended from Frankish and Norman Germanic lineages and often bore Germanic names such as Charles de Gaulle, though his family Y chromosome DNA has not been tested. The name “de Gaulle” likely came from “De Walle” which in German means “the wall" of a fortification or city.

Following the successful example of a Cornish-Viking alliance in 722 at the Battle of Hehil, which helped stop the Anglo-Saxon conquest of Cornwall at the time, the people of Brittany (Bretons) made friendly overtures to the Danish Vikings in an effort to counter Frankish expansionism. In 866 the Vikings and Bretons united to defeat a Frankish army at the Battle of Brissarthe, resulting in formal recognition of Brittany's independence.

The Vikings continued to tactically help their Breton allies by devastating Frankish areas under the Carolingians with pillaging raids. In 885, one of the minor Viking leaders named Rollo helped in the siege of Paris under the command of Danish king Sigfred. When Sigfred retreated in return for tribute the following year, Rollo stayed behind and was eventually bought off and sent to bother Burgundy by the Frankish king, Charles the Simple. Later, he returned to the Seine with a group of Danish followers who were called "Men of the North" or Norsemen. They invaded the area of northern France now known as Normandy.

Rather than pay Rollo to leave, as was customary, Charles the Simple realized that his armies could not effectively defend against the raids and guerrilla tactics, and decided to appease Rollo by giving him land and hereditary titles under the condition that he defend against other Vikings. Led by Rollo, the Vikings settled in Normandy after being granted the land. They subsequently established the Duchy of Normandy. The descendants who emerged from the interactions of Vikings, Franks, and Gallo-Romans became known as Normans. This may explain why a noticeably higher than average rate of men living in northwestern France today are I1.[27]

The Scandinavian colonisation of Normandy was principally Danish, complemented by a strong Norwegian contingent, although a few Swedes were present.[citation needed] The Viking colonization was not a mass phenomenon, but they established themselves rather densely in some areas, particularly Pays de Caux and the northern part of the Cotentin. Toponymic and linguistic evidence supports this theory. The merging of the Scandinavian and native populations contributed to the creation of one of the most powerful feudal states of Western Europe. The naval ability of the Normans would allow them to conquer England, and participate in the Crusades.

Spain and Portugal

The presence of I1 is attested at 10% to 16% levels in areas of the N.W. Iberian peninsula in the countries of Portugal and Spain. Their inland presence is harder to explain than the coastal areas, as well as the age, STR, etc

Scandinavia

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2008) |

Russia

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2008) |

From the ninth and into the tenth centuries, Scandinavian raiders and merchants travelled to Russia, Belarus and Ukraine, known as Varangians by the Byzantines.[28] The Varangians have been described as a warrior elite or nobility.

Varangian leader Rurik is credited with founding the first Rus state. Although recent genetic studies have identified two major royal lines within Russian society, R1a and N1c1a,[29] genetic research shows significant I1 contribution centering on Moscow.[30](dead link)

John Haywood, author of The Great Migrations, believes that a group known as the Rus preceded the Varangians. However, most identify the Rus people as a particular Varangian tribe. A large burial mound in Novgorod Oblast, Russia, known as a tumulus and dating from the ninth century, is similar to those found in Old Uppsala, Sweden. It is reportedly well-defended against potential looters and has never been excavated. Local residents refer to it as 'Rurik's Grave'.

Scandinavians remained in control of areas such as Kiev until at least the mid-eleventh century.[31] They became the nucleus of the Rus state, whose Golden Age in the eleventh and early twelfth centuries came to an abrupt end with the Mongol invasion of 1240.

Their campaigns are commemorated on many runestones in both Norway and Sweden, among them the Greece Runestones and the Varangian Runestones. The last major expedition appears to have been the ill-fated expedition of Ingvar the Far-Travelled to Serkland, a region southeast of the Caspian Sea, commemorated by the Ingvar Runestones. What happened to the men is not known.

Greece and Turkey

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2008) |

Another branch of Varangians dominated the Byzantine Empire military elite for a time. This could be the precursor of spikes in I1 haplotypes in Turkey and Greece near Istanbul. A military unit known as the Varangian Guard was established by Emperor Basil II. After Rus military recruits helped him quell a rebellion, Basil II formed an alliance with Vladimir I of Kiev and organized the guard. New recruits from Sweden, Denmark, and Norway continued the Scandinavian predominance of the guard until the late eleventh century. So many Swedes left to enlist in the guard that a medieval Swedish law stated that no man could gain his inheritance while remaining in Greece.[32] In The History of the Crusades author Steve Runciman noted that by the time of the Emperor Alexius, the Byzantine Varangian Guard was largely recruited from Anglo-Saxons in England and "others who had suffered at the hands" of the Vikings and the Normans.

There can also be other explanations for I1* Y-DNA's in Turkey. Tatar Turks are known to be over 18% I1* and this would be a reasonable explanation for the high I1* rates in Istanbul as many Crimean Tatars served the Ottoman Empire as administrators and military figures.

Haplotypes

Modal

Ken Nordtvedt has given the following 'modal haplotypes' within the I1 haplogroup according to examples found in I1 populations.[33] Many I1-Norse types have been found to be downstream of the P109 SNP, concretely defining it as a haplogroup subclade and giving further credence to Nordtvedt's method of haplotyping.[34] Furthermore, SNP L22 has been discovered to be upstream of P109, encompassing all of P109s Norse types, additional Norse types without P109 as well as Ultra Norse types excluded from the pool of P109 positives.

Such haplotyping is necessary because currently more resolution of potential subclades through matching STR alleles exists than is available via testing for known subclade SNPs in haplogroup I1.

I1 Anglo-Saxon (I1-AS) Has its peak gradient in the Germanic lowland countries: northern Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands, as well as England and old Norman regions of France.[citation needed] Template:DYS Template:DYS

I1 Norse (I1-N) Has its peak gradient in Sweden. Template:DYS Template:DYS

I1 Ultra-Norse Type 1 (I1-uN1) Has its peak gradient in Norway. Template:DYS Template:DYS

Many other Nordtvedt haplotypes exist, and Nordtvedt has continually refined the haplogroup with more types as they become apparent as more I1 types are tested.

Famous

Alexander Hamilton, through genealogy and the testing of his descendants, has been placed within Y-DNA haplogroup I1.[35]

Mutations

The following are the technical specifications for known I1 haplogroup SNP and STR mutations.

Name: M253[36]

- Type: SNP

- Source: M (Peter Underhill, Ph.D. of Stanford University)

- Position: ChrY:13532101..13532101 (+ strand)

- Position (base pair): 283

- Total size (base pairs): 400

- Length: 1

- ISOGG HG: I1

- Primer F (Forward 5′→ 3′): GCAACAATGAGGGTTTTTTTG

- Primer R (Reverse 5′→ 3′): CAGCTCCACCTCTATGCAGTTT

- YCC HG: I1

- Nucleotide alleles change (mutation): C to T

Name: M307[37]

- Type: SNP

- Source: M (Peter Underhill, Ph.D. of Stanford University)

- Position: ChrY:21160339..21160339 (+ strand)

- Length: 1

- ISOGG HG: I1

- Primer F: TTATTGGCATTTCAGGAAGTG

- Primer R: GGGTGAGGCAGGAAAATAGC

- YCC HG: I1

- Nucleotide alleles change (mutation): G to A

Name: P30[38]

- Type: SNP

- Source: PS (Michael Hammer, Ph.D. of the University of Arizona and James F. Wilson, D.Phil. at the University of Edinburgh)

- Position: ChrY:13006761..13006761 (+ strand)

- Length: 1

- ISOGG HG: I1

- Primer F: GGTGGGCTGTTTGAAAAAGA

- Primer R: AGCCAAATACCAGTCGTCAC

- YCC HG: I1

- Nucleotide alleles change (mutation): G to A

- Region: ARSDP

Name: P40[39]

- Type: SNP

- Source: PS (Michael Hammer, Ph.D. of the University of Arizona and James F. Wilson, D.Phil. at the University of Edinburgh)

- Position: ChrY:12994402..12994402 (+ strand)

- Length: 1

- ISOGG HG: I1

- Primer F: GGAGAAAAGGTGAGAAACC

- Primer R: GGACAAGGGGCAGATT

- YCC HG: I1

- Nucleotide alleles change (mutation): C to T

- Region: ARSDP

Name: DYS455[40]

- Type: STR (repeat)

- Position: ChrY:6971459..6971638 (+ strand)

- Length: 180

- Primer F: ATCTGAGCCGAGAGAATGATA

- Primer R: GGGGTGGAAACGAGTGTT

Popular culture

In the book Blood of the Isles, published in North America as Saxons, Vikings & Celts: The Genetic Roots of Britain and Ireland, author Bryan Sykes gave the name of the Nordic deity Wodan to represent the clan patriarch of I1, as he did for mitochondrial haplogroups in a previous book, The Seven Daughters of Eve. Every male identified as I1 is a descendant of this man.

Another writer, Stephen Oppenheimer, discussed I1 in his book The Origins of the British. Although somewhat controversial, Oppenheimer, unlike Sykes, argued that Anglo-Saxons did not have much impact on the genetic makeup of the British Isles. Instead he theorized that the vast majority of British ancestry originated in a paleolithic Iberian people, traced to modern-day Basque populations, represented by the predominance of Haplogroup R1b in the United Kingdom today.[41] The book When Scotland Was Jewish is another example. These are direct challenges to previous studies led by Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, Siiri Rootsi and others.[42] Cavalli-Sforza has studied the connections between migration patterns and blood groups. There has been some discussion of this on a mailing list at RootsWeb.[43]

Spencer Wells gave a brief description of I1 in the book Deep Ancestry: Inside The Genographic Project.

See also

References

- ^ Tatiana M. Karafet et al., New binary polymorphisms reshape and increase resolution of the human Y chromosomal haplogroup tree, Genome Research, doi:10.1101/gr.7172008 (2008)

- ^ Clade I Information from 2008 Research Paper (Karafet et al.)

- ^ Annals of Human Genetics. Volume 72 Issue 3 Page 337-348, May 2008

- ^ RootsWeb: Discussion on Y-DNA-HAPLOGROUP-I Mailing List

- ^ New Phylogenetic Relationships for Y-chromosome Haplogroup I: Reappraising its Phylogeography and Prehistory

- ^ Nordtvedt Overview of New Phylogenetic Relationships for Y-chromosome Haplogroup I

- ^ "No Consensus on Viking Influence". Archived from the original on 2009-10-31.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Y-Haplogroup Predictor

- ^ Allele Frequency Among I1a Samples

- ^ Signature Markers

- ^ Excavating Y-chromosome haplotype strata in Anatolia

- ^ Reconstruction of Patrilineages and Matrilineages of Samaritans and Other Israeli Populations From Y-Chromosome and Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Variation

- ^ Y-DNA Haplogroup I and its Subclades - 2008

- ^ Ecclesiastical History of England

- ^ Britain BC: Life in Britain and Ireland before the Romans by Francis Pryor, p. 122. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-00-712693-X.

- ^ Anglo-Saxon Origins: The Reality of the Myth by Malcolm Todd. Retrieved 1 October 2006.

- ^ Y chromosome Evidence for Anglo-Saxon Mass Migration" (2002) Michael E. Weale, Deborah A. Weiss, Rolf F. Jager, Neil Bradman and Mark G. Thomas. Molecular Biology and Evolution 19:1008-1021

- ^ "English and Welsh are races apart" BBC News. June 2002

- ^ "A Y Chromosome Census of the British Isles" (2003) Cristian Capelli, Nicola Redhead, Julia K. Abernethy, Fiona Gratrix, James F. Wilson, Torolf Moen, Tor Hervig, Martin Richards, Michael P.H. Stumpf, Peter A. Underhill, Paul Bradshaw, Alom Shaha, Mark G. Thomas, Neal Bradman, and David B. Goldstein Current Biology Vol 13, 979-984 doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00373-7

- ^ British Have Changed Little Since Ice Age, Gene Study Says

- ^ Ecclesiastical History of the English People

- ^ The Origins of the British by Stephen Oppenheimer

- ^ Summarization of Rootsi Paper by Nordtvedt

- ^ Germans set up an apartheid-like society in Britain

- ^ I1a Samples in Western Europe from ySearch

- ^ Nordtvedt on I1a, Northern France and the Vikings

- ^ Territory with Norman Influence

- ^ Viking Description from The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition

- ^ Vikings in Russia, Rurikid Dynasty DNA Project

- ^ Map of I1a in Russia (dead link)

- ^ Michael Psellus: Chronographia, ed. E. Sewter, (Yale University Press, 1953), 91. and R. Jenkins, Byzantium: The Imperial Centuries AD 610-1071 (Toronto 1987) p. 307

- ^ Jansson 1980:22

- ^ Y-DNA Haplogroup I Modal Haplotypes - with Markers in FTDNA Order

- ^ I1a and P109 & P109 as Individual I1a SNP

- ^ Founding Father DNA & Hamilton DNA Project Results Discussion

- ^ M253

- ^ M307

- ^ P30

- ^ P40

- ^ DYS455

- ^ "Myths of British Ancestry," Prospect Magazine

- ^ Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup I Reveals Distinct Domains of Prehistoric Gene Flow In Europe

- ^ Blood groups and Haplogroup I

Further reading

- Y-chromosome diversity in Sweden – A long-time perspective

- Y chromosome evidence for Anglo-Saxon mass migration

- A Y Chromosome Census of the British Isles

- Resolving the Placement of Haplogroup I-M223 in the Y-Chromosome Phylogenetic Tree

- Human Y-Chromosomal Variation in European Populations

- Oppenheimer, Stephen The Origins of the British: A Genetic Detective Story (Carroll & Graf, 2006) ISBN 978-0786718900

- Sykes, Bryan Saxons, Vikings, and Celts: The Genetic Roots of Britain and Ireland (W. W. Norton, 2006) ISBN 978-0393062687

External links

- Haplogroup I Subclade Predictor

- I HG Y-chromosome research by Ken Nordtvedt

- Nordvedt's Haplogroup I Clusters with STR Markers in FTDNA Order

- Danish Demes Regional DNA Project: Y-DNA Haplogroup I1 (I-M253) Results

- Danish Demes Regional DNA Project: Y-DNA Haplogroups I1d (I-L22) and I1d1 (I-P109) Results

- Testing for the S-series of SNPs within Haplogroup I1 (Called I1a)

- Distribution of Repeat Values at Various STR Sites for Haplogroup I1 (Called I1a)

- Haplogrou I1 discussion forum at FTDNA (requires membership to view threads)

- Haplogroup I1 DYS frequencies according to Geographical Locale (Called I1a)

- Dienekes Anthropology page; I1 as modal haplotype of Western Norway (Called I1a)

- Mailing List for Y-DNA Haplogroup I

- Haplogroup I and Its Subclades