Browser wars

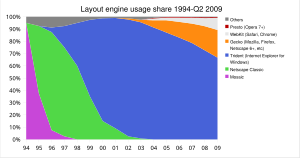

Source: Median values from summary table.

Browser wars is a metaphorical term that refers to competitions for dominance in usage share in the web browser marketplace. The term is often used to denote two specific rivalries: the competition that saw Microsoft's Internet Explorer replace Netscape's Navigator as the dominant browser during the late 1990s and the erosion of Internet Explorer's market share since 2003 by a collection of emerging browsers including Mozilla Firefox, Google Chrome, Safari, and Opera.

Background

This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: This time is often referred as "Mosaic Wars". (March 2010) |

The World Wide Web is an Internet-based hypertext system invented in the late 1980s and early 1990s by Tim Berners-Lee. Berners-Lee wrote the first web browser WorldWideWeb, later renamed Nexus, and released it for the NeXTstep platform in 1991.

By the end of 1992 other browsers had appeared, many of them based on the libwww library. These included Unix browsers such as Line Mode Browser, ViolaWWW, Erwise and MidasWWW, and MacWWW/Samba for the Mac. This created choice between browsers and hence the first real competition, especially on Unix.

Mosaic wars

There are two ages of the Internet - before Mosaic, and after. The combination of Tim Berners-Lee's Web protocols, which provided connectivity, and Marc Andreesen's browser, which provided a great interface, proved explosive. In twenty-four months, the Web has gone from being unknown to absolutely ubiquitous

— A Brief History of Cyberspace, Mark Pesce, ZDNet, October 15, 1995

Further browsers were released in 1993, including Cello, Arena, Lynx, tkWWW and Mosaic. The most influential of these was Mosaic, a multiplatform browser developed at National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA). By October 1994, Mosaic was "well on its way to becoming the world's standard interface", according to Gary Wolfe of Wired.[1]

Several companies licensed Mosaic to create their own commercial browsers, such as AirMosaic and Spyglass Mosaic. One of the Mosaic developers, Marc Andreessen, founded Mosaic Communications Corporation and created a new web browser named Mosaic Netscape. To resolve legal issues with NCSA, the company was renamed Netscape Communications Corporation and the browser Netscape Navigator. The Netscape browser improved on Mosaic's usability and reliability and was able to display pages as they loaded. By 1995, helped by the fact that it was free for non-commercial use, the browser dominated the emerging World Wide Web.

Other browsers launched during 1994 included IBM Web Explorer, Navipress, SlipKnot, MacWeb, and Browse.[2]

In 1995, Netscape faced new competition from OmniWeb, WebRouser, UdiWWW, and Microsoft's Internet Explorer 1.0, but continued to dominate the market.

The first browser war

By mid-1995 the World Wide Web had received a great deal of attention in popular culture and the mass media. Netscape Navigator was the most widely used web browser and Microsoft had licensed Mosaic to create Internet Explorer 1.0,[3][4] which it had released as part of the Microsoft Windows 95 Plus! Pack in August.[5]

Internet Explorer 2.0 was released as a free download three months later. Unlike Netscape Navigator it was available to all Windows users for free, even commercial companies.[6] Other companies later followed and gave their browsers away for free.[7] Both Netscape Navigator and competitor products like InternetWorks, Quarterdeck Browser, InterAp, and WinTapestry were bundled with other applications to full internet suites.[7] New versions of Internet Explorer and Netscape (branded as Netscape Communicator) were released at a rapid pace over the following few years.

Development was rapid and new features were routinely added, including Netscape's JavaScript (subsequently replicated by Microsoft as JScript) and proprietary HTML tags such as <blink> and <marquee>.

Internet Explorer began to approach feature parity with Netscape with version 3.0 (1996), which offered scripting support and the market's first commercial Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) implementation.

In October 1997, Internet Explorer 4.0 was released. The release party in San Francisco featured a ten-foot-tall letter "e" logo. Netscape employees showing up to work the following morning found the giant logo on their front lawn, with a sign attached that read "From the IE team ... We Love You". The Netscape employees promptly knocked it over and set a giant figure of their Mozilla dinosaur mascot atop it, holding a sign reading "Netscape 72, Microsoft 18" representing the market distribution.[8]

Internet Explorer 4 changed the tides of the browser wars. It was integrated into Microsoft Windows, which IT professionals and industry critics considered technologically disadvantageous and an apparent exploitation of Microsoft's monopoly on the PC platform. Users were discouraged from using competing products because IE was "already there" on their PCs.[citation needed]

During these releases it was common for web designers to display 'best viewed in Netscape' or 'best viewed in Internet Explorer' logos. These images often identified a specific browser version and were commonly linked to a source from which the stated browser could be downloaded. These logos generally recognized the divergence between the standards supported by the browsers and signified which browser was used for testing the pages. In response, supporters of the principle that web sites should be compliant with World Wide Web Consortium standards and hence viewable with any browser started the "Viewable With Any Browser" campaign, which employed its own logo similar to the partisan ones.

Internet Explorer 5 & 6

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2009) |

Microsoft had three strong advantages in the browser wars.

One was resources: Netscape began with about 80% market share and a good deal of public goodwill, but as a relatively small company deriving the great bulk of its income from what was essentially a single product (Navigator and its derivatives), it was financially vulnerable. Netscape's total revenue never exceeded the interest income generated by Microsoft's cash on hand. Microsoft's vast resources allowed IE to remain free as the enormous revenues from Windows were used to fund its development and marketing. Netscape was commercial software for businesses but provided for free for home and education users; Internet Explorer was provided as free for Windows users, cutting off a significant revenue stream: As it was told by Jim Barksdale, President and CEO of Netscape Communications: "Very few times in warfare have smaller forces overtaken bigger forces..."[9]

Another advantage was that Microsoft Windows had over 90% share of the desktop operating system market. IE was bundled with every copy of Windows; therefore Microsoft was able to dominate the market share easily as customers had IE as a default. In this time period, many new computer purchases were first computer purchases for home users or offices, and many of the users had never extensively used a web browser before, so had nothing to compare with and little motivation to consider alternatives; the great set of features they had gained in gaining access to the Internet and the World Wide Web at all made any modest differences in browser features or ergonomics pale in comparison.

During the United States Microsoft antitrust case in 1998, Intel vice president Steven McGeady, a witness called by the government, said on the stand that a senior executive at Microsoft told him in 1995 of his company's intention to "cut off Netscape's air supply". Microsoft attorney said that McGeady's testimony is not credible.[10] That same year, Netscape, the company, was acquired by America Online for USD $4.2 billion. Internet Explorer became the new dominant browser, attaining a peak of about 96% of the web browser usage share during 2002, more than Netscape had at its peak.

The first browser war ended with Internet Explorer having no remaining serious competition for its market share. This also brought an end to the rapid innovation in web browsers; until 2006 there was only one new version of Internet Explorer since version 6.0 had been released in 2001. Internet Explorer 6.0 Service Pack 1 was developed as part of Windows XP SP1, and integrated into Windows Server 2003. Further enhancements were made to Internet Explorer in Windows XP SP2 (released in 2004), including a pop-up blocker and stronger default security settings against the installation of ActiveX controls.

Consequences

The browser wars encouraged three specific kinds of behavior among their combatants.

- Adding new features instead of fixing bugs: A web browser had to have more new features than its competitor, or else it would be considered to be "falling behind." But with limited manpower to put towards development, this often meant that quality assurance suffered and that the software was released with serious bugs.

- Adding proprietary features instead of obeying standards: A web browser is expected to follow the standards set down by standards committees (for example, by adhering to the HTML specifications) in order to assure interoperability of the Web for all users. But competition and innovation led to web browsers "extending" the standards with proprietary features (such as the HTML tags <font>, <marquee>, and <blink>) without waiting for committee approval. Sometimes these extensions produced useful features that were adopted by other browsers, such as the XMLHttpRequest technology that resulted in Ajax.

- Inadvertently creating security loopholes: In the race to add development features, the line between document and application is crossed, and the Active Content Exploit is born. This is because, whenever applications have been allowed to masquerade as documents (e.g. Master Mode, Office macros, etc.) anyone can slip malicious code into what is otherwise a trustworthy format. As a virus scanner can only detect a virus that is old enough to be catalogued (usually more than 48 hours), it cannot protect against a zero day attack. Thus this blurring of the boundary between application and document creates an easy access point that is the basis for delivery of nearly all of today's drive-by downloads and auto-loading malicious code.[citation needed]

Support for web standards was severely weakened. For years, innovation in web development stagnated as developers had to use obsolete and unnecessarily complex techniques to ensure their pages would render properly in Netscape Navigator and Internet Explorer. Netscape Navigator 4 and IE6 lacked full compliance with several standards, including CSS and the PNG image format.

On February 2, 2008 the last update to Netscape Navigator 9 was released, based on Mozilla Firefox 2. However, it never regained its market share. Netscape was discontinued on March 1, 2008.

The second browser war

After the defeat of Navigator by Internet Explorer, Netscape open-sourced their browser code, and entrusted it to the newly formed non-profit Mozilla Foundation—a primarily community-driven project to create a successor to Netscape. Development continued for several years with little widespread adoption until a stripped-down browser-only version of the full suite was created, which included features, such as tabbed browsing and a separate search bar, that had previously only appeared in Opera. The browser-only version was initially named Phoenix, but because of trademark issues that name was changed, first to Firebird, then to Firefox. This browser became the focus of the Mozilla Foundation's development efforts and Mozilla Firefox 1.0 was released on November 9, 2004. Since then it has continued to gain an increasing share of the browser market, until a peak in 2010, after which it has remained largely stable.

In 2003, Microsoft announced that Internet Explorer 6 Service Pack 1 would be the last standalone version of its browser. Future enhancements would be dependent on Windows Vista, which would include new tools such as the WPF and XAML to enable developers to build extensive Web applications.

In response, in April 2004, the Mozilla Foundation and Opera Software joined efforts to develop new open technology standards which add more capability while remaining backward-compatible with existing technologies.[12] The result of this collaboration was the WHATWG, a working group devoted to the fast creation of new standard definitions that would be submitted to the W3C for approval.

2006–2007

On February 15, 2005, Microsoft announced that Internet Explorer 7 would be available for Windows XP SP2 and later versions of Windows by mid-2005.[13] The announcement introduced the new version of the browser as a major upgrade over Internet Explorer 6 SP1.

Opera had been a long-time small player in the browser wars, known for introducing innovative features such as tabbed browsing and mouse gestures, as well as being lightweight but feature-rich. The software, however, was commercial, which hampered its adoption compared to its free rivals until 2005, when the browser became freeware. On June 20, 2006, Opera Software released Opera 9 including an integrated source viewer, a BitTorrent client implementation and widgets. It was the first Windows browser to pass the Acid2 test. Opera Mini, a mobile browser, has significant mobile market share as well as being available on the Nintendo DS and Wii.

On October 18, 2006, Microsoft released Internet Explorer 7. It included tabbed browsing, a search bar, a phishing filter, and improved support for Web standards — all features already familiar to Opera and Firefox users. Microsoft distributed Internet Explorer 7 to genuine Windows users (WGA) as a high priority update through Windows Update.[14] Typical market share analysis showed only a slow uptake of Internet Explorer 7 and Microsoft decided to drop the requirement for WGA and made Internet Explorer 7 available to all Windows users in October 2007.[15]

On October 24, 2006, Mozilla released Mozilla Firefox 2.0. It included the ability to reopen recently closed tabs, a session restore feature to resume work where it had been left after a crash, a phishing filter and a spell-checker for text fields.

In 2002 Apple created a fork of the open-source KHTML and KJS layout and javascript engines from the KDE project Konqueror browser, explaining that those would provide easier development than other technologies by virtue of being small (fewer than 140,000 lines of code), cleanly designed and standards compliant,[16] now known as WebKit project. A Safari browser was first shipped with Mac OS X v10.3. In June 13, 2003 Microsoft said it was discontinuing their browser on the Mac platform. On June 6, 2007, Apple released their initial beta version of Safari for Microsoft Windows.

On December 19, 2007, Microsoft announced that an internal build of Internet Explorer 8 has passed the Acid2 CSS test in "IE8 standards mode" – the last of the major browsers to do so.

On December 28, 2007, Netscape announced that support for its Mozilla-derived Netscape Navigator would be discontinued on February 1, 2008, suggesting its users migrate to Mozilla Firefox.[17] However, on January 28, 2008, Netscape announced that support would be extended to March 1, 2008, and mentioned Flock, alongside Firefox, as an alternative to its users.

2008–2010

Mozilla released Firefox 3.0 on June 17, 2008,[18] with performance improvements, and other new features. Firefox 3.5 followed on June 30, 2009 with further performance improvements, native integration of audio and video, and more privacy features.[19]

Google released the Chrome browser for Microsoft Windows on December 11, 2008, using the same WebKit rendering engine as Safari and a faster JavaScript engine called V8. An open sourced version for the Windows, Mac OS X and Linux platforms was released under the name Chromium. According to Net Applications, Chrome had gained a 3.6% usage share by October 2009. After the release of the beta for Mac OS X and Linux, the market share had increased rapidly.[20]

On March 19, 2009, Microsoft released Internet Explorer 8, which added accelerators, improved privacy protection, a compatibility mode for pages designed for Internet Explorer 7[21] and improved support for various web standards.

according to Statcounter

During December 2009 and January 2010, StatCounter reported that its statistics indicated that Firefox 3.5 was the most popular browser, when counting individual browser versions, passing Internet Explorer 7 and 8 by a small margin.[22][23] This is the first time a global statistic has reported that a non-Internet Explorer browser version has exceeded the top Internet Explorer version in usage share since the fall of Netscape Navigator. This feat, which GeekSmack called the "dethron[ing of] Microsoft and its Internet Explorer 7 browser,"[24] can largely be attributed to the fact that it came at a time when IE 8 was replacing IE 7 as the dominant Internet Explorer version. No more than two months later IE 8 had established itself as the most popular browser version, a position which it still holds as of March 2011. It should also be noted that other major statistics, such as Net Applications, never report any non-IE browser version as having a higher usage share than the most popular Internet Explorer version, although Firefox 3.5 was reported as the third most popular browser version between December 2009 and February 2010, to be replaced by Firefox 3.6 since April 2010, each ahead of IE7 and behind IE6 and IE8.[25]

On January 21, 2010, Mozilla released Mozilla Firefox 3.6, which allows support for a new type of theme display, 'Personas', which allows users to change Firefox's appearance with a single click. Version 3.6 also improves JavaScript performance, overall browser responsiveness and startup times.[26]

In October 2010, StatCounter reported that Internet Explorer had for the first time dropped below 50% market share to 49.87% in their figures.[27] Also, StatCounter reported Internet Explorer 8's first drop in usage share in the same month.[28]

Race to HTML5

On February 3, 2011, Google released Chrome 9. New features introduced include: support for WebGL, Chrome Instant, and the Chrome Web Store.[29]

StatCounter global market share figures were as follows for February 2011. Internet Explorer 45%, Firefox 30%, Chrome 17%, Safari 5%, and Opera 2%, leaving all the others sharing the remaining 1%.[30]

On March 8, 2011, Google released Chrome 10. New features can be found on the blogspot release. [31]

On March 14, 2011, Microsoft released Internet Explorer 9.

On March 22, 2011, Mozilla released Firefox 4.0.[32]

On April 4, 2011, Google released Chrome 11.

On June 7, 2011, Google released Chrome 12. [33]

On June 21, 2011, Mozilla released Firefox 5.0.[34]

On August 2, 2011, Google released Chrome 13.[35]

On August 16, 2011, Mozilla released Firefox 6.0.[36]

On September 15, 2011, Google released Chrome 14. [37]

On September 27, 2011, Mozilla release Firefox 7.0. [38]

In development

Microsoft's Internet Explorer 10 which supports Windows 7 or later.

Google's Chrome 15 and Chrome 16, in Beta and Dev respectively.

Mozilla's Firefox 10, in Alpha.

Opera Software's Opera 12, in pre-Alpha.

Other browser competition

Microsoft Windows

Although its usage share has been dropping since the mid-2000s,[39] Internet Explorer still has, as of January 2011, the largest usage share on Microsoft Windows, with Mozilla Firefox the second most used web browser. Google Chrome, released in September 2008,[40] is gaining ground in third place.[41] In March 2008, Apple released Safari 3.1, began including it as a pre-selected update in the Apple Software Update program[42] and its market share on Windows tripled.[43] It is now in fourth place followed by Opera.[41] Other browsers based on Internet Explorer's Trident layout engine, such as Maxthon, included features like tabbed browsing and were once popular but fell out of use when IE began adding such features itself from version 7 onwards.

Linux and Unix

The Unix-based Konqueror browser is part of the KDE project and is the primary competitor against Mozilla-based browsers (Firefox, Mozilla Application Suite/SeaMonkey, Epiphany, Galeon, etc.) for market share on Unix-like systems. Konqueror's KHTML engine is an API for the KDE desktop. Derivative browsers and web-browsing functionality (for example, Amarok has a Wikipedia sidebar that gives information about the current artist) based on KDE use KHTML.[44]

Mac OS X

Safari is Apple's web browser for Mac OS X, and also has the highest usage share on Mac OS X.[45] The web browser is based on WebKit, a derivative of the KHTML engine. Other Mac browsers including iCab (since 4.0), OmniWeb (since 4.5), and Shiira, use the WebKit API, and many other Macintosh programs add web-browsing functionality through WebKit.[46] Mozilla Firefox and Opera Browser also have high usage on Mac OS X.

Camino is a Mozilla-based Gecko browser for the Mac OS X platform, and uses Mac's native Cocoa interface like Safari does, instead of Mozilla's XUL which is used in Firefox. It was initially developed by Dave Hyatt, until he was hired by Apple to develop Safari.

Embedded devices

Opera Mini is a popular web browser on mobile devices such as most Java ME enabled internet connected phones and smartphones because of its small footprint. It has also recently been released for the iPhone and iPod Touch. Opera Mobile for smartphones main competition is from Netfront. Sony developed a mobile browser for their PSP, using Netfront's codebase. Sony's PlayStation 3 also includes a web browser. PC Site Viewer, the web browser included on many Japanese cellular phones, is based on Opera. In February, 2006 it was announced that Nintendo "will release an add-on card" with a version of Opera for the Nintendo DS (Nintendo DS Browser).[47] This DS browser has since been criticized for its lack of Flash support and slowness.[48] Opera is also used as a web browser on the Wii console.

Nokia released a WebKit-based browser in 2005,[49] which comes with every Symbian S60 platform-based smartphone. On Nokia's N900 is MicroB, a Firefox derivate, preinstalled. It competes with Opera for the N900.

Windows Phone 7 comes with a version of Internet Explorer Mobile with a rendering engine which Steve Ballmer said to be "somewhere between Internet Explorer 7 and Internet Explorer 8". Microsoft plans to update the layout engine to that of Internet Explorer 9.

Windows Mobile comes with Internet Explorer Mobile by default and competes with Opera Mobile, Netfront, Iris, and Mozilla's Minimo, and lately the Skyfire browser (also available for Android and Symbian).

MobileSafari, Apple's browser based on WebKit/KHTML, comes with iPhone, iPod Touch and the iPad.

Android, Google's open-source OS for mobile devices, uses a browser based on WebKit. Since March 2010, Opera Mini has been available for Android.[50] Other browsers include Opera Mobile and Firefox 4.

See also

Notes

- ^ Wolfe, Gary (1994). "The (Second Phase of the) Revolution Has Begun". Wired Magazine. Retrieved 2006-12-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Berghel, Hal (2 April 1996). "Hal Berghel's Cybernautica". Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ Elstrom, Peter (22 January 1997). "MICROSOFT'S $8 MILLION GOODBYE TO SPYGLASS". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ Thurrott, Paul (22 January 1997). "Microsoft and Spyglass kiss and make up". WindowsITPro. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ "Windows History: Internet Explorer History". Microsoft.com. 2003-06-30. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "Microsoft Internet Explorer Web Browser Available on All Major Platforms, Offers Broadest International Support" (Press release). Microsoft. 30 April 1996. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ a b Berst, Jesse (20 February 1995). "Web-Wars". PC Week. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ "Mozilla stomps IE". Home.snafu.de. 1997-10-02. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "Roads and Crossroads of the Internet History". NetValley.com. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

- ^ Chandrasekaran, Rajiv (1998). "Microsoft Attacks Credibility of Intel Exec". Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ http://gs.statcounter.com/#browser-ww-monthly-200807-201106

- ^ "Position Paper for the W3C Workshop on Web Applications and Compound Documents". W3.org. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "IEBlog : IE7". Blogs.msdn.com. 2005-02-15. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ Evers, Joris. "Microsoft tags IE 7 'high priority' update | CNET News.com". News.com.com. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "IEBlog: Internet Explorer 7 Update". Blogs.msdn.com. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ KDE KFM-Devel mailing list "(fwd) Greetings from the Safari team at Apple Computer", January 7, 2003.

- ^ "The Netscape Blog". Netscape, AOL. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

- ^ "Coming Tuesday, June 17th: Firefox 3". Mozilla Developer Center. Retrieved 2009-10-12.

- ^ "Mozilla Advances the Web with Firefox 3.5". Mozilla Europe and Mozilla Foundation. Retrieved 2009-10-12. [dead link]

- ^ "Window Internet Explorer 8 Fact Sheet" (Press release). Microsoft. March 2009. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ Firefox 3.5 is world's most popular browser, StatCounter says, Nick Eaton. seattlepi blogs. 2009-12-21. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ^ "StatCounter global stats – Top 12 browser versions". StatCounter. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ^ "Firefox 3.5 surpasses IE7 market share". Geeksmack.net. 2009-12-22. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ^ "Browser market share trend". Marketshare.hitslink.com. Retrieved 2010-06-25.

- ^ "Mozilla Firefox 3.6 Release Notes". Mozilla.com. 2010-01-21. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ^ "Microsoft Internet Explorer browser falls below 50% of worldwide market for first time". StatCounter. Retrieved 7 october 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "StatCounter Browser Versions form Oct 09 to Oct 10". StatCounter. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ "Google Chrome Blog". chrome.blogspot.com. 2011-02-03. Retrieved 2010-02-04.

- ^ "StatCounter global stats – Top 5 browsers". StatCounter. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

Hover mouse on the data points for figures

- ^ "Google Chrome Blog". chrome.blogspot.com. 2011-03-08. Retrieved 2011-03-12.

- ^ "Damon Sicore announces possible Firefox 4.0 final launch date in the official Mozilla Google Groups page".

- ^ "Chrome Stable".

- ^ "Mozilla Delivers New Version of Firefox – First Web Browser to Support Do Not Track on Multiple Platforms".

- ^ "Google Chrome Releases - Stable Channel".

- ^ "Firefox 6 Is Launching Tuesday, Here's What You Need To Know".

- ^ "Chrome Stable Release".

- ^ "Here's What's New In Firefox 7".

- ^ "Browser Stats". The Counter.Com. QuinStreet. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ "Google Chrome". Google.com. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ a b "Top Browser Share Trend". Net Applications. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^

Stone, Brad (created May 26, 2008). "Browsers Are a Battleground Once Again". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "KDE 2 Architecture Overview – KDE's HTML Library". Developer.kde.org. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ Dotzler, Asa (December 6, 2008). "market share by platform". Mozilla. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ^ "BYOB: Build Your Own Browser". MacDevCenter.com. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "Technology | Nintendo DS looks beyond gamers". BBC News. 2006-02-16. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "IGN: Nintendo DS Browser Review". Ds.ign.com. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ s60.com

- ^ "Opera Mini 5 beta for Android". my.opera.com. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

References

- DOJ/Antitrust: U.S. Department of Justice Antitrust Division. Civil Action No. 98-1232 (Antitrust) Complaint, United States of America v. Microsoft Corporation. May 18, 1998. Press release: Justice Department Files Antitrust Suit Against Microsoft for Unlawfully Monopolizing Computer Software Markets

External links

- Browser Statistics – Month by month comparison spanning from 2002 and onward displaying the usage share of browsers among web developers.

- Browser Stats – Chuck Upsdell's Browser Statistics

- Browser Stats – Net Applications' Browser Statistics

- StatCounter Global Stats – tracks the market share of browsers including mobile from over 4 billion monthly page views.

- Browser war, RIA and future of web development

- Browser Wars II: The Saga Continues – an article about the development of the browser wars

- Thomas Haigh, "Protocols for Profit: Web and Email Technologies as Product and Infrastructure" in The Internet & American Business, eds. Ceruzzi & Aspray, MIT Press, 2008– business & technological history of web browsers, online preprint

- stephenbrooks.org – browserwars – a multiplayer browser game, shows the logo of the browsers used