The Wizard of Oz

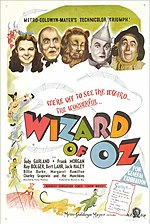

The Wizard of Oz is a 1939 American musical fantasy film produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. It was directed primarily by Victor Fleming. Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson and Edgar Allan Woolf received credit for the screenplay, but there were uncredited contributions by others. The lyrics for the songs were written by E.Y. Harburg, the music by Harold Arlen. Incidental music, based largely on the songs, was by Herbert Stothart, with borrowings from classical composers.

Based on the 1900 children's novel, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum,[1] the film stars Judy Garland, Ray Bolger, Jack Haley, Bert Lahr, and Frank Morgan, with Billie Burke, Margaret Hamilton, Charley Grapewin, Clara Blandick and the Singer Midgets as the Munchkins.[2] Notable for its use of special effects, Technicolor, fantasy storytelling and unusual characters, It has become, over the years, one of the best known of all films.

Although it received largely positive reviews, it was initially a box office failure.[3] The film was MGM's most expensive production up to that time, but its initial release failed to recoup the studio's investment. Subsequent re-releases made up for that, however.[3] It was nominated for six Academy Awards, including Best Picture. It lost that award to Gone with the Wind, but won two others, including Best Original Song for "Over the Rainbow".

Telecasts of it began in 1956, re-introducing the film to the public and eventually becoming an annual tradition, making it one of the most famous films ever made.[1] The film was named the most-watched motion picture in history by the Library of Congress,[4] is often ranked among the Top 10 Best Movies of All Time in various critics' and popular polls, and is the source of many memorable quotes referenced in modern popular culture.

Plot

Kansas farm girl Dorothy Gale (Judy Garland) lives with her Aunt Em (Clara Blandick), Uncle Henry (Charley Grapewin), and three farm hands, Hickory (Jack Haley), Hunk (Ray Bolger), and Zeke (Bert Lahr). When Miss Almira Gulch (Margaret Hamilton) is bitten by Dorothy's pet Cairn Terrier, Toto, she gets a sheriff's order and takes him away to be destroyed. He escapes and returns to Dorothy, who, fearing for his life, runs away with him.

Dorothy soon encounters a traveling fortune teller named Professor Marvel (Frank Morgan), who guesses she has run away and tells her fortune. He convinces her to return home by falsely telling her that Aunt Em has fallen ill from grief. With a tornado fast approaching, she rushes back to the farmhouse, but is unable to join her family in the locked storm cellar. Taking shelter inside the house, she is knocked unconscious by a window frame blown in by the twister.

Dorothy awakens to find the house being carried away by the tornado. After it falls back to earth, she opens the door and finds herself alone in a strange village. Arriving in a floating bubble, Glinda, the Good Witch of the North (Billie Burke), informs her that her house landed on and killed the Wicked Witch of the East.

The timid Munchkins come out of hiding to celebrate the Witch's demise by singing "Ding-Dong! The Witch Is Dead". Their celebration is interrupted when the Wicked Witch of the West (Margaret Hamilton) suddenly appears in a cloud of smoke and tries to claim her dead sister's powerful ruby slippers. But Glinda magically transfers them onto Dorothy's feet and reminds the Witch of the West that her power is ineffectual in Munchkinland. She promises Dorothy "I'll get you, my pretty...and your little dog, too!" before leaving the same way she arrived. When Dorothy asks how to get back home, Glinda advises her to seek the help of the mysterious Wizard of Oz in the Emerald City, which she can reach by following the Yellow Brick Road, and warns her never to remove the ruby slippers or she will be at the mercy of the Wicked Witch.

On her way to the city, Dorothy meets a Scarecrow (Ray Bolger), a Tin Man (Jack Haley), and a Cowardly Lion (Bert Lahr), who lament to her that they respectively lack a brain, a heart, and courage. The three decide to accompany her in hopes that the Wizard will also fulfill their desires, although they demonstrate that they already have the qualities they believe they lack: the Scarecrow has several good ideas, the Tin Man is kind and sympathetic, and the Lion, though terrified, is ready to face danger.

After Dorothy and the Cowardly Lion nearly succumb to one of the Witch's traps, the quartet enters the Emerald City and is allowed to see the Wizard, who appears amidst smoke and flames as a disembodied, intimidating head. In a booming voice, he states that he will consider granting their wishes if they bring him the Wicked Witch's broomstick.

They set out for the Witch's castle, but she detects them and dispatches her army of flying monkeys, who carry Dorothy and Toto back to her. When the Witch threatens to drown Toto, Dorothy agrees to give up the ruby slippers, but a shower of sparks prevents their removal. Realizing they can't be removed unless Dorothy dies, the Witch leaves to ponder how to accomplish this.

Toto escapes and leads Dorothy's companions to the castle. After overpowering some of the Winkie guards and disguising themselves in their uniforms, they find and free her. The Witch and the Winkies corner the group on a parapet, where she sets the Scarecrow's arm ablaze with her broomstick. Dorothy throws water on her friend and accidentally splashes the Witch, causing her to melt. The Winkies are delighted, and their captain gives Dorothy the broomstick.

Upon their triumphant return to the Wizard's chamber, Toto opens a curtain, revealing him to be an ordinary man (Frank Morgan) operating a console of wheels and levers while speaking into a microphone. Apologetic, he explains that Dorothy's companions already possess what they have been seeking all along, but bestows upon them tokens of esteem in recognition of their respective virtues. Explaining that he too was born in Kansas, and was brought to Oz by a runaway hot air balloon, he offers to take Dorothy home in the same balloon, leaving the Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Lion in charge of the Emerald City.

As they are about to leave, Toto jumps out of the balloon's basket and Dorothy runs after him. The Wizard, unable to control the balloon, leaves without her. As she despairs of ever getting back home, Glinda appears and tells her that she always had the power to return home, but that she needed to learn for herself that she didn't have to run away to find her heart's desire. She bids her friends goodbye, then follows Glinda's instructions to close her eyes, tap her heels together three times, and keep repeating "There's no place like home".

Dorothy awakens in her bedroom in Kansas, surrounded by family and friends, and tells them of her journey. Although Auntie Em assures her it was all a dream, Dorothy insists it was real and promises never to run away from home again.

Differences from the novel

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2011) |

Many details are omitted or altered, while many of the perils that Dorothy encountered in the novel are not at all mentioned in the feature film. Oz, and Dorothy's time there, is real in the book, not just a dream. The Good Witch of the North (who has no name in the book), Glinda the Good Witch of the South, and the Queen of the Field Mice are merged into one omniscient character, Glinda the Good Witch of the North. To take advantage of the new vivid Technicolor process, Dorothy's silver shoes were changed to ruby slippers for the movie. Due to time constraints, a number of incidents from the book, including the Dainty China Country and the Hammerheads, were cut. The role of the Wicked Witch of the West was also enlarged for the movie (in the book, although she is mentioned several times before, she is only present for one chapter towards the end). This was done to provide more dramatic tension throughout the film, and to unify what is otherwise a very episodic plot. The role and character of Dorothy were also transformed: in the film, she is depicted as a damsel in distress who needs to be rescued, while in the novel, she, a little girl, rescues her friends, in keeping with Baum's feminist sympathies.

There are at least 44 identifiable major differences between the original book and this movie interpretation.[5][6] Nevertheless, the film was far more faithful to Baum's original book than many earlier scripts (see below) or film versions. Two silent versions were produced in 1910 and 1925 and the seven-minute animated cartoon in 1933 (the 1925 version, with which Baum, who had died six years earlier, had no association, made Dorothy a Queen of Oz, rather like the later sci-fi TV miniseries Tin Man). The 1939 movie interprets the Oz experience as a dream, in which many of the characters that Dorothy meets represent the people from her home life (such as Miss Gulch, Professor Marvel, and the farmhands, none of whom appear in the book). In L. Frank Baum's original novel, Oz is meant to be a real place, one that Dorothy would return to in his later Oz books and which would later provide a refuge for Aunt Em and Uncle Henry after being unable to pay the mortgage on the new house that was built after the old one really was carried away by the tornado. Also in the novel, the four travelers were required to wear magic spectacles before entering the Emerald City. [7]

Cast

- Judy Garland as Dorothy Gale

- Frank Morgan as Professor Marvel / Doorman / Cabbie / Guard / The Wizard

- Ray Bolger as Hunk / Scarecrow

- Jack Haley as Hickory / Tin Man

- Bert Lahr as Zeke / Cowardly Lion

- Billie Burke as Glinda the Good Witch of the North

- Margaret Hamilton as Miss Almira Gulch / The Wicked Witch of the West

- Clara Blandick as Aunt Em

- Charley Grapewin as Uncle Henry

- Pat Walshe as Nikko (the Head Flying Monkey)

- Terry[8] as Toto (Credited as Toto in the film)

- The Singer Midgets as the Munchkins

- Mitchell Lewis as the Winkie Guard Captain (uncredited)

None of the Singer Midgets' actual voices are heard in the film; their vocalizations were dubbed by professional singers and voice actors, including Pinto Colvig, Abe Dinovitch and Billy Bletcher, and singing groups The King's Men, The Debutantes and Ken Darby Singers. [9] Although the Wicked Witch's guards spoke their own dialogue, their singing was also dubbed by others and was slowed down.[citation needed] Adriana Caselotti voiced Juliet, and Abe Dinovitch and Candy Candido voiced the Apple Trees.[10]

Pat Walshe was the last surviving significant member of the cast when he died in December 1991, aged 91.[11] Meinhardt Raabe was one of the last surviving Munchkin actors, and the last surviving cast member with any dialogue when he died in April 2010, aged 94. [12]

Production

Color and sepia tone

All of the Oz sequences were filmed in three-strip Technicolor.[13][14] The opening and closing credits, as well as the Kansas sequences, were filmed in black and white and colored in a sepia tone process.[13] Sepia-toned film was also used in the scene where Aunt Em appears in the Wicked Witch's crystal ball.

In his book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Baum describes Kansas as being 'in shades of gray'. Further, Dorothy lived inside a farmhouse which had its paint blistered and washed away by the weather, giving it an 'air of grayness'. The house and property were situated in the middle of a sweeping prairie where the grass was burnt gray by harsh sun. Aunt Em and Uncle Henry were 'gray with age'. Effectively, the use of monochrome sepia tones for the Kansas sequences was a stylistic choice that evoked the dull and gray countryside.[citation needed] Much attention was given to the use of color in the production, with the MGM production crew favoring some hues over others. Consequently, it took the studio's art department almost a week to settle on the final shade of yellow used for the Yellow Brick Road.[15]

Development and pre-production

Development of the film started when the success of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs showed that films adapted from popular children's stories and fairytale folklore could be successful.[13][16] In January 1938, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer bought the rights to the hugely popular novel from Samuel Goldwyn, who had toyed with the idea of making the film as a vehicle for Eddie Cantor, who was under contract to the Goldwyn studios and whom Goldwyn wanted to cast as the Scarecrow.[13]

The script went through a number of writers and revisions before the final shooting.[14] Originally, Mervyn LeRoy's assistant William H. Cannon submitted a brief four-page outline.[citation needed] Because recent fantasy films had not fared well at the box office, he recommended that the magical elements of the story be toned down or eliminated. In his outline, the Scarecrow was a man so stupid that the only way he could get employment was to dress up as a scarecrow and scare away crows in a cornfield, and the Tin Woodman was a hardened criminal so heartless he was sentenced to be placed in a tin suit for eternity. The torture of being encased in the suit had softened him and made him gentle and kind.[citation needed] His vision was similar to Larry Semon's 1925 film adaptation of the story, in which the magical element is absent.

After that, LeRoy hired screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz to work on a script. Despite Mankiewicz's notorious reputation at that time for being an alcoholic, he soon delivered a 17-page one of the Kansas scenes, and a few weeks later, he handed in a further 56 pages. Noel Langley and poet Ogden Nash were also hired to write separate versions of the story. None of the three writers involved knew anyone else was working on a script, but it was not an uncommon procedure. Nash soon delivered a four page outline, Langley turned in a 43-page treatment and a full film script. He turned in three more, this time incorporating the songs that had been written by Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg. No sooner had he completed it than Florence Ryerson and Edgar Allan Woolf submitted a script and were brought on board to touch up the writing. They would be responsible for making sure the story stayed true to the Baum book. During filming, Victor Fleming and John Lee Mahin revised the script further, adding and cutting some scenes. In addition, Jack Haley and Bert Lahr are known to have written some of their own dialogue for the Kansas sequence.

The final draft of the script was completed on October 8, 1938, following numerous rewrites.[17] All in all, it was a mish-mash of many creative minds, but Langley, Ryerson and Woolf got the film credits. Along with the contributors already mentioned, others who assisted with the adaptation without receiving official credit include: Irving Brecher, Herbert Fields, Arthur Freed, E. Y. Harburg, Samuel Hoffenstein, Jack Mintz, Sid Silvers, Richard Thorpe, George Cukor and King Vidor.[13]

In addition, songwriter Harburg's son (and biographer) Ernie Harburg reports,[18]

So anyhow, Yip also wrote all the dialogue in that time and the setup to the songs and he also wrote the part where they give out the heart, the brains and the nerve, because he was the final script editor. And he — there was eleven screenwriters on that — and he pulled the whole thing together, wrote his own lines and gave the thing a coherence and unity which made it a work of art. But he doesn’t get credit for that. He gets lyrics by E. Y. Harburg, you see. But nevertheless, he put his influence on the thing.

The original producers thought that a 1939 audience was too sophisticated to accept Oz as a straight-ahead fantasy; therefore, it was reconceived as a lengthy, elaborate dream. Because of a perceived need to attract a youthful audience through appealing to modern fads and styles, the script originally featured a scene with a series of musical contests. A spoiled, selfish princess in Oz had outlawed all forms of music except classical and operetta and went up against Dorothy in a singing contest in which her swing style enchanted listeners and won the grand prize. This part was initially written for Betty Jaynes.[19] The plan was later dropped.

Another scene, which was removed before final script approval and never filmed, was a concluding scene back in Kansas after Dorothy's return. Hunk (the Kansan counterpart to the Scarecrow) is leaving for agricultural college and extracts a promise from Dorothy to write to him. The implication of the scene is that romance will eventually develop between the two, which also may have been intended as an explanation for Dorothy's partiality for the Scarecrow over her other two companions. This plot idea was never totally dropped, however; it is especially noticeable in the final script when Dorothy, just before she is to leave Oz, tells the Scarecrow, "I think I'll miss you most of all."[20]

Casting

Mervyn LeRoy had always insisted that he wanted to cast Judy Garland to play Dorothy from the start; however, evidence suggests that negotiations took place early in pre-production for Shirley Temple to play the part of Dorothy, on loan out from 20th Century Fox. A persistent rumor also existed that Fox was in turn promised Clark Gable and Jean Harlow as a loan from MGM. The tale is almost certainly untrue, as Harlow died in 1937, before MGM had even purchased the rights to the story. Despite this, the story appears in many film biographies (including Temple's own autobiography). The documentary The Wonderful Wizard of Oz: The Making of a Movie Classic states that Mervyn LeRoy was under pressure to cast Temple, then the most popular child star; but at an unofficial audition, MGM musical mainstay Roger Edens listened to her sing and felt that an actress with a different style was needed. Newsreel footage is included in which Temple wisecracks, "There's no place like home," suggesting that she was being considered for the part at that time.[21] A possibility is that this consideration did indeed take place, but that Gable and Harlow were not part of the proposed deal.

Actress Deanna Durbin, who was under contract to Universal, was also considered for the part of Dorothy. Durbin, at the time, far exceeded Garland in film experience and fan base and the two had co-starred in a 1936 two-reeler called Every Sunday. The film was most notable for exhibiting Durbin's operatic style of singing against Garland's jazzier style. Durbin was possibly passed over once it was decided to bring on Betty Jaynes, also an operatic singer, to rival Garland's jazz in the aforementioned discarded subplot of the film.

Casting The Wizard of Oz was problematic, with two actors swapping roles prior to the start of filming. Ray Bolger was originally cast as the Tin Man and Buddy Ebsen (later famous for his role as Jed Clampett on the popular 1960s TV show The Beverly Hillbillies) was to play the Scarecrow.[17] Bolger, however, longed to play the Scarecrow, as his childhood idol Fred Stone had done on stage in 1902; with that very performance, Stone had inspired him to become a vaudevillian in the first place. Now unhappy with his role as the Tin Man (reportedly claiming, "I'm not a tin performer; I'm fluid"), Bolger convinced producer Mervyn LeRoy to recast him in the part he so desired.[22] Ebsen did not object; after going over the basics of the Scarecrow's distinctive gait with Bolger (as a professional dancer, Ebsen had been cast because the studio was confident he would be up to the task of replicating the famous "wobbly-walk" of Stone's Scarecrow), he recorded all of his songs, went through all the rehearsals as the Tin Man, and began filming with the rest of the cast.[23]

Gale Sondergaard was originally cast as the Wicked Witch. She became unhappy when the witch's persona shifted from sly and glamorous (thought to emulate the wicked queen in Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs) into the familiar "ugly hag." She turned down the role and was replaced on October 10, 1938, just three days before filming started, by MGM contract player Margaret Hamilton. Sondergaard said in an interview for a bonus feature on the DVD that she had no regrets about turning down the part, and would go on to play a glamorous villain in Fox's version of Maurice Maeterlinck's The Blue Bird in 1940; that same year, Margaret Hamilton would play a role remarkably similar to the Wicked Witch in the Judy Garland film Babes in Arms.

On July 25, 1938, Bert Lahr was signed for the Cowardly Lion; Charles Grapewin was cast as Uncle Henry on August 12.

W. C. Fields was originally chosen for the role of the Wizard, but the studio ran out of patience after protracted haggling over his fee; instead, another contract player, Frank Morgan, was cast on September 22. According to Aljean Harmetz, when the wardrobe department was looking for a coat for Morgan, they decided that they wanted a once elegant coat that had "gone to seed". They went to a second-hand shop and purchased a whole rack of coats, from which Morgan, the head of the wardrobe department and director Fleming chose one they thought had the perfect appearance of shabby gentility. One day, while he was on set wearing the coat, Morgan turned out one of the pockets and discovered a label indicating that the coat had once belonged to Oz author L. Frank Baum. Mary Mayer, a unit publicist for the film, contacted the tailor and Baum's widow, who both verified that the coat had indeed once belonged to the writer. After filming was completed, the coat was presented to Mrs. Baum. Baum biographer Michael Patrick Hearn disbelieves the story, it having been refuted by members of the Baum family, who never saw the coat or knew of the story, as well as by Margaret Hamilton, who considered it a concocted studio rumor.[24]

Filming

Filming commenced October 13, 1938 on the MGM Studios lot in Culver City, California, under the direction of Richard Thorpe (replacing original director Norman Taurog, who only filmed a few early Technicolor tests and was then reassigned). Thorpe initially shot about two weeks of footage (nine days, total) involving Dorothy's first encounter with the Scarecrow, as well as a number of sequences in the Wicked Witch's castle, such as Dorothy's rescue (which, though unreleased, comprises the only footage of Buddy Ebsen's Tin Man).

Ten days into the shoot, however, Ebsen suffered a reaction to the aluminum powder makeup he wore; the powder he breathed in daily as it was applied had coated his lungs. Ebsen was hospitalized in critical condition, and subsequently was forced to leave the project; in a later interview (included on the 2005 DVD release of Wizard of Oz), Ebsen recalled the studio heads initially disbelieving that he was seriously ill, only realizing the extent of the actor's condition when they showed up in the hospital as he was convalescing in an iron lung. Ebsen's sudden medical departure caused the film to shut down while a new actor was found to fill the part. No full footage of Ebsen as the Tin Man has ever been released — only photographs taken during filming and test photos of different makeup styles remain. MGM did not publicize the reasons for Ebsen's departure until decades later, in a promotional documentary about the film. His replacement, Jack Haley, simply assumed he had been fired.[25]

Producer Mervyn LeRoy had taken this time to review the already shot footage and felt that Thorpe seemed to be rushing the picture along, creating a negative impact on the actors' performances; thus, LeRoy decided to have Thorpe replaced. Despite being let go from the production, however, some of Thorpe's footage would be retained in the final edit, such as close-ups of the Scarecrow sans Dorothy during his first scene (due to a major subsequent change in the Dorothy character makeup, wide shots and close-ups of Judy Garland from the days of that shoot could not be used), as well as certain sequences too expensive to reorganize and reshoot, including the entirety of the Winkies' march outside the Witch's castle during the climax of the film — right up to when the Scarecrow, Lion, and Buddy Ebsen's Tin Man (though his face is not seen) sneak into the castle behind the marchers. [citation needed]

During reorganization on the production, George Cukor temporarily took over, under LeRoy's guidance. Initially, the studio had made Garland wear a blond wig and heavy, "baby-doll" makeup, and she played Dorothy in an exaggerated fashion; now, Cukor changed Judy Garland's and Margaret Hamilton's makeup and costumes, and told Garland to "be herself." This meant that all the scenes Garland and Hamilton had already completed had to be discarded and re-filmed. Cukor also suggested that the studio cast Jack Haley, on loan from 20th Century Fox, as the Tin Man. To keep down on production costs, Haley only rerecorded "If I Only Had a Heart" and solo lines during "The Jitterbug" and "If I Only Had the Nerve"; as such, Buddy Ebsen's voice can still be heard in the remaining songs featuring the Tin Man in group vocals. The makeup used for Haley was quietly changed to an aluminum paste, with a layer of clown white greasepaint underneath to protect his skin; although it did not have the same dire effect on Haley, he did at one point suffer from an unpleasant eye infection from it.

In addition, Ray Bolger's original recording of "If I Only Had a Brain" had been far more sedate compared to the version heard in the film; during this time, Cukor and LeRoy decided that a more energetic rendition would better suit Dorothy's initial meeting with the Scarecrow (initially, it was to contrast with his lively manner in Thorpe's footage), and was re-recorded as such. At first thought to be lost for over seven decades, a recording of this original version was rediscovered in 2009.[26]

Cukor did not actually shoot any scenes for the film, merely acting as something of a "creative advisor" to the troubled production, and, because of his prior commitment to direct Gone with the Wind, he left on November 3, 1938, at which time Victor Fleming assumed the directorial responsibility. As director, Fleming chose not to shift the film from Cukor's creative realignment, as producer LeRoy had already pronounced his satisfaction with the new course the film was taking.

Production on the bulk of the Technicolor sequences was a long and cumbersome process that ran for over six months, from October 1938 to March 1939. Most of the actors worked six days a week and had to arrive at the studio as early as four or five in the morning, to be fitted with makeup and costumes and would not leave until seven or eight at night. Cumbersome makeup and costumes were compounded by the fact that the early Technicolor process required a significant amount of lighting to be used (due to the low ASA speed of the film), which would usually heat the set to over a hundred degrees. According to Ray Bolger, most of the Oz principals were banned from eating in the studio's commissary due to their costumes. Margaret Hamilton's makeup meant that food could not be ingested and so she practically lived on a liquid diet during filming of the Oz sequences. Additionally, it took upwards of 12 takes to have Dorothy's dog Toto run alongside the actors as they skipped down the Yellow Brick Road.

The massive shoot also proved to be somewhat chaotic. This was most evident when trying to put together the Munchkinland sequences. MGM talent scouts searched the country far and wide to come up with over a hundred little people who would make up the citizens of Munchkinland; this meant that most of the film's Oz sequences would have to already be shot before work on the Munchkinland sequence could begin. According to Munchkin actor Jerry Maren, each little person was paid over $125 a week for their performances. Munchkin Meinhardt Raabe, who played the coroner, revealed in the 1990 documentary The Making of the Wizard of Oz that the MGM costume and wardrobe department, under the direction of designer Adrian, had to design over one hundred costumes for the Munchkin sequences. They then had to photograph and catalog each Munchkin in his or her costume so that they could correctly apply the same costume and makeup each day of production.

Filming even proved to be dangerous, at times. Margaret Hamilton was severely burned in the Munchkinland scene. There was a little elevator that was supposed to take her down, with a fire erupting to dramatize and conceal her exit. As told by Hamilton in archival audio included on the DVD commentary, the first take went smoothly, and that was the one eventually used in the film. For the second take, the timing was off, and she was exposed to the flames. Her copper-based makeup had to be completely and quickly removed before her face could be treated, and her hands were also burned.

On February 12, 1939, Victor Fleming hastily replaced George Cukor in directing Gone with the Wind; the next day, King Vidor was assigned as director by the studio to finish the filming of The Wizard of Oz (mainly the sepia Kansas sequences, including Judy Garland's singing of "Over the Rainbow"). In later years, when the film became firmly established as a classic, Vidor chose not to take public credit for his contribution until after the death of his friend Fleming in 1949.

Post-production

Principal photography concluded with the Kansas sequences on March 16, 1939; nonetheless re-shoots and pick-up shots were filmed throughout April, May and into June, under the direction of producer LeRoy. After the deletion of the "Over the Rainbow" reprise during subsequent test screenings in early June, Judy Garland had to be brought back one more time in order to reshoot the "Auntie Em, I'm frightened!" scene without the song; the footage of Clara Blandick's Auntie Em, as shot by Vidor, had already been set aside for rear projection work, and was simply reused. After Margaret Hamilton's torturous experience with the Munchkinland elevator, she refused to do the pick-ups for the scene in which she flies on a broomstick which billows smoke, so LeRoy chose to have stand-in Betty Danko perform the scene instead; as a result, Danko was severely injured doing the scene due to a malfunction in the smoke mechanism.[27]

At this point, the film began a long arduous post-production. Herbert Stothart had to compose the film's background score, while A. Arnold Gillespie had to perfect the various special effects that the film required, including many of the rear projection shots. The MGM art department also had to create the various matte paintings for the background of many of the scenes.

One significant innovation for the film was the use of "stencil printing" which was used for the transition to Technicolor: Each frame was to be hand-tinted to maintain the sepia tone; however, because this was too expensive and labor intensive, it was abandoned and MGM used a simpler and less expensive variation of the process. During the re-shoots in May, the inside of the farm house was painted sepia, and when Dorothy opens the door, it is not Garland but her stand-in, Bobbie Koshay, wearing a sepia gingham dress, who then backs out of frame; once the camera moves through the door, Garland steps back into frame in her bright blue gingham dress (as noted in DVD extras), and the sepia-painted door briefly tints her with the same color before she emerges from the house's shadow, into the bright glare of the Technicolor lighting. This also meant that the re-shoots provided the first proper shot of Munchkinland; if one looks carefully, the brief cut to Dorothy looking around outside the house bisects a single long shot, from the inside of the doorway to the pan-around that finally ends in a reverse-angle as the ruins of the house are seen behind Dorothy as she comes to a stop at the foot of the small bridge.

Test screenings of the film began on June 5, 1939.[28] Oz initially was running nearly two hours long. LeRoy and Fleming knew that at least a quarter of an hour needed to be deleted to get the film down to a manageable running time, the average film in 1939 running just about 90 minutes. Three sneak previews in Santa Barbara, Pomona and San Luis Obispo, California helped guide LeRoy and Fleming in the cutting. Among the many cuts was "The Jitterbug" number, the Scarecrow's elaborate dance sequence following "If I Only Had A Brain", a reprise of "Over the Rainbow" and "Ding Dong the Witch Is Dead", and a number of smaller dialogue sequences. This left the final, mostly serious portion of the film with no songs, only the dramatic underscoring.

One song that was almost deleted was "Over the Rainbow". MGM had felt that it made the Kansas sequence too long, as well as being far over the heads of the target audience of children. The studio also thought that it was degrading for Judy Garland to sing in a barnyard. Producer Mervyn LeRoy, uncredited associate producer Arthur Freed, and director Victor Fleming fought to keep it and eventually won. The song went on to win the Academy Award for Best Song of the Year. In 2004, the song was ranked #1 by the American Film Institute on AFI's 100 Years…100 Songs list.

After the preview in San Luis Obispo in early July, The Wizard of Oz was officially released in August 1939 at its current 101-minute running time.

Errors

Several errors were made during the final editing with the film. The scene after the Wicked Witch of the West throws a fireball at the Scarecrow is completely flipped in the film as while being put together the film strip was accidentally backwards subsequently putting the scene in a mirror view and the scene right afterwards is correct. Another error in the film was the Wicked Witch's line of "I sent a little insect on ahead to take the fight out of them.", which references the dropped "Jitterbug" number, was left in the final film.

Release

The film was previewed in three test markets: on August 11, 1939, at Kenosha, Wisconsin and Cape Cod, Massachusetts,[29][30] and at the Strand Theatre in Oconomowoc, Wisconsin on August 12.[31]

The Hollywood premiere was on August 15, 1939,[30] at Grauman's Chinese Theatre.[citation needed] The New York City premiere at Loew's Capitol Theatre on August 17, 1939 was followed by a live performance with Judy Garland and her frequent film co-star Mickey Rooney. They would continue to perform there after each screening for a week, extended in Rooney's case for a second week and in Garland's to three (with Oz co-stars Ray Bolger and Bert Lahr replacing Rooney for the third and final week). The movie opened nationally on August 25, 1939.

The film grossed approximately $3 million (approximately $66 million today) against production/distribution costs of $2.8 million (approximately $61 million today) in its initial release. It did not show what MGM considered a large profit until a 1949 re-release earned an additional $1.5 million (approximately $19 million today).

Reception

Frank S. Nugent said the film was a "delightful piece of wonder-working which had the youngsters' eyes shining and brought a quietly amused gleam to the wiser ones of the oldsters"; he said "not since Disney's Snow White has anything quite so fantastic succeeded half so well.[32] Nugent had issues with some of the film's special effects, saying "with the best of will and ingenuity, they cannot make a Munchkin or a Flying Monkey that will not still suggest, however vaguely, a Singer's Midget in a Jack Dawn masquerade. Nor can they, without a few betraying jolts and split-screen overlappings, bring down from the sky the great soap bubble in which the Good Witch rides and roll it smoothly into place." According to Nugent, "Judy Garland's Dorothy is a pert and fresh-faced miss with the wonder-lit eyes of a believer in fairy tales, but the Baum fantasy is at its best when the Scarecrow, the Woodman and the Lion are on the move."[32]

In current reviews, The Wizard of Oz is still highly praised by critics. On the film's Rotten Tomatoes listing, 100% of critics give the film positive reviews, based on 70 reviews.[33]

Re-releases

Beginning with the 1949 reissue, and continuing until the film's 50th anniversary VHS release in 1989, the opening Kansas sequences were shown in black and white instead of the sepia tone as originally filmed.[34]

This was done despite the fact that the sepia had been specifically chosen for the picture to help mask the switch to Technicolor.[citation needed] The actual switch occurs before the door is opened from the transported house onto the Land of Oz. In the sepia prints, one doesn't notice any color until that door is opened, because the door itself is a shade of brown which matches the sepia. In black and white, one cannot help but notice the switch to color before the door is opened, which was precisely what the film's producers wanted to avoid. For the film's 50th anniversary restoration, the sepia was brought back to the opening and closing Kansas scenes and beginning in 1990, the film was shown on CBS television nationally as originally released in 1939. It was also very common (and even an FCC requirement for early color broadcasters) for TV stations to turn off the color portion of their transmission when broadcasting a black and white show or movie. This was because unusual colors or "color noise" could be seen during the showing of black-and-white programming under some conditions. Though the opening Kansas scenes in The Wizard of Oz were meant to be shown in sepia and though the sepia was restored to the film in 1989 for the film's 50th anniversary VHS and laserdisc reissue, a few local CBS affiliates still showed the sepia portion of the film with the color signal disabled for many years. [citation needed] Most of these were small market affiliates that ran some syndicated black-and-white shows as these stations were used to turning the color modes off during black-and-white programming. One CBS affiliate, WGNX, transmitted the opening Kansas scenes in black and white as recently as its 1996 showing because this station was an independent station that ran a moderate number of black-and-white films before becoming a CBS affiliate.

1955 saw the release of a widescreen 1.85:1 aspect ratio version to theatres, with portions of the top and the bottom of the film removed via soft mattes to produce a widescreen effect. The re-release trailer falsely claimed that "every scene" from Baum's novel was in the film, including "the rescue of Dorothy", though there is no such incident in the novel.

The MGM "Children's Matinees" series re-released the film twice, in 1970 and 1971.[35]

In 1986, the film was acquired by Turner Entertainment as part of a deal involving a majority of MGM's pre-1986 library. In 1996, Turner merged with Time Warner, and since then Warner Bros. Pictures has been handling distribution for all media on Turner's behalf.

The film was re-released again in U.S. theaters by WB on November 6, 1998. The version was a newly restored and remastered print with a remixed stereo soundtrack. It also featured restoration and sound remixing credits at the end (none of these extra credits have appeared on any video release).

In 1999, the film had a theatrical re-release in Australia, in honor of the film's 60th anniversary.

In 2002, the film had a very limited re-release in the U.S. theaters.[36]

On September 23, 2009, The Wizard of Oz was re-released in select theaters for a one-night-only event in honor of the film's 70th Anniversary and as a promotion for various new disc releases later in the month. An encore of this event was re-released in theaters on November 17, 2009.[37]

Television

The film was first shown on television November 3, 1956 on CBS, as the last installment of the Ford Star Jubilee, making it, historically, the first uncut Hollywood film shown in one evening on a commercial television network. The Oz scenes were shown in color (posters still exist advertising the broadcast and they specifically say in color and black-and-white), but because most television sets then were not color sets, few members of the TV audience saw the film that way. An estimated 45 million people watched the broadcast. However, it was not rerun until three years later. On December 13, 1959 the film was shown (again on CBS) as a two-hour Christmas season special and at an earlier time, to an even larger audience (commercial breaks were much shorter then, enabling the film to run in a two-hour time slot without being cut). Encouraged by the response, CBS decided to make it an annual Christmas tradition, showing it from 1959 through 1962 always on the second Sunday of December. The film was not shown in December 1963 as might have been expected, perhaps due to the proximity of the John F. Kennedy assassination, which occurred on November 22 of that year and plunged the U.S. into a period of mourning. Others say that there was no room on the schedule, because by then there were other Christmas specials on television, though not nearly as many as there would be in later years (A Charlie Brown Christmas, How the Grinch Stole Christmas! and Frosty the Snowman, all first shown on CBS in the 1960s, were still more than two years away, and NBC did not premiere Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer until December of 1964).

Whatever the reason, the telecast was moved from December 1963 to the evening of January 26, 1964. The 1964 broadcast marked the end of the Christmas season showings, but The Wizard of Oz was nevertheless still televised only once a year for nearly three decades. Beginning in 1967, showing of the film was moved to February, and after that the date of the showings would constantly shift, rather than always occurring in the same month. That same year, the film was bought for annual TV showings by NBC, whose telecasts of it began in April 1968, but by 1976, it had reverted to CBS. CBS dropped its broadcasts of the film in 1998; the rights are now in the hands of Turner Entertainment (through Warner Bros. Television), and the film is now shown several times a year (rather than annually) on or just before several notable holidays (including Easter, the Fourth of July, Thanksgiving and/or Christmas). Turner Classic Movies cable channel, TNT and the TBS Superstation now often show the film during the same week "in rotation."[38]

For the film's first nine telecasts, all on CBS, the film featured on-camera celebrity hosts, who provided commentary (often comic) and information about the making of the film. The hosts for these telecasts were a young Liza Minnelli, Bert Lahr, and Justin Schiller (Oz historian and the founder and first president of "The International Wizard Of Oz Club"), all hosting the first telecast, Red Skelton and his daughter Valentina, (the second telecast), Richard Boone and his son Peter (the third telecast), Dick Van Dyke and his children (the fourth and fifth telecasts), and Danny Kaye (the sixth, seventh, eighth, and ninth telecasts).[39][40][41][42][43]

Home video

The Wizard of Oz was among the first videocassettes released by MGM/CBS Home Video in 1980;[44] all current home video releases are by Warner Home Video (via current rights holder Turner Entertainment). The first laserdisc release of The Wizard of Oz was in 1982, with two versions of a second, (one from Turner and one from The Criterion Collection with a commentary track) for the 50th Anniversary release in 1989, a third in 1991, a fourth in 1993, a fifth in 1995 and a sixth and final laserdisc release on September 11, 1996.[45]

The first DVD release of the film was on March 26, 1997 by MGM and contained no special features or supplements. It was re-released by Warner Bros. for its 60th Anniversary on October 19, 1999, in snapper case packaging with its soundtrack presented in a new 5.1 surround sound mix. The monochrome-to-color transition was more smoothly accomplished by digitally keeping the inside of the house in monochrome while Dorothy and the reveal of Munchkinland are in color. The DVD also contained an extensive behind-the-scenes documentary: The Wonderful Wizard of Oz: The Making of a Movie Classic, produced in 1990 and hosted by Angela Lansbury, which was originally featured in the 1993 "Ultimate Oz" laserdisc box set release. Despite being a one-disc release, outtakes, the deleted "Jitterbug" musical number, clips of pre-1939 Oz adaptations, trailers, newsreels and a portrait gallery were also included, as well as two radio programs of the era publicizing the film.

In 2005, two new DVD editions were released, both featuring a newly restored version of the film with audio commentary and an isolated music and effects track. One of the two DVD releases was a "Two-Disc Special Edition", featuring production documentaries, trailers, various outtakes, newsreels, radio shows and still galleries. The other set, a "Three-Disc Collector's Edition", included these features as well as the digitally restored 80th anniversary edition of the 1925 feature-length silent film version of The Wizard of Oz, other silent Oz movies, and a 1933 animated short version.

The Wizard of Oz was released on Blu-ray Disc on September 29, 2009 for the film's 70th anniversary in a four-disc "Ultimate Collector's Edition", including all the bonus features from the 2005 Collector's Edition DVD, new bonus features about Victor Fleming and the surviving Munchkins, the telefilm The Dreamer of Oz: The L. Frank Baum Story and the miniseries MGM: When the Lion Roars. The Blu-ray Disc version of Oz features a significant picture quality increase over all previous home video releases due to Warner commissioning a new transfer at 8K resolution from the original film negatives, a feat which required 22 terabytes of storage space. This master was then used to create the 22 gigabyte 1080p encode for the Blu-ray Disc which runs at an average 23 Mbit/s bitrate using the VC-1 codec. This restored version also features a lossless 5.1 Dolby TrueHD audio track.[46] A DVD version was also released as a Two-Disc Special Edition and a Five-Disc Ultimate Collector's Edition. As previously mentioned, the September 23, 2009 one-day-only theatrical 70th anniversary showings were also a promotion for the various disc releases six days later.

On December 1, 2009,[citation needed] three discs of the Ultimate Collector's Edition Blu-ray Disc were repackaged as a less expensive "Emerald Edition," with an Emerald Edition four-disc DVD arriving the following week. A single-disc Blu-ray, containing the restored movie and all the extra features of the two-disc Special Edition DVD, also became available on March 16, 2010.[citation needed]

Music

The Wizard of Oz is widely noted for its musical selections and soundtrack. Music & lyrics were by Harold Arlen and E.Y. "Yip" Harburg, who won the Academy Awards for Best Music Song for "Over the Rainbow." In addition, Herbert Stothart, who composed the instrumental underscore, won the Academy Award for Best Original Score. Georgie Stoll was associate conductor and screen credit was given to George Bassman, Murray Cutter, Ken Darby and Paul Marquardt for orchestral and vocal arrangements. (As usual Roger Edens was also heavily involved as an unbilled musical associate to Freed).

The song "The Jitterbug", written in a swing style, was intended for the sequence in which the four are journeying to the castle of the Wicked Witch of the West. Due to time constraints, the song was cut from the final theatrical version. The film footage for the song has been lost, although silent home film footage of rehearsals for the number has survived. The sound recording for the song, however, is intact and was included in the 2-CD Rhino Records deluxe edition of the film soundtrack, as well as on the VHS and DVD editions of the film. A reference to "The Jitterbug" remains in the film: the Witch remarks to her flying monkeys that they should have no trouble apprehending Dorothy and her friends because "I've sent a little insect on ahead to take the fight out of them."

Another musical number that was cut before release occurred right after the Wicked Witch of the West was melted and before Dorothy and her friends returned to the Wizard. This was a reprise of "Ding! Dong! The Witch is Dead" (blended with "We're Off to See the Wizard" and "The Merry Old Land of Oz") with the lyrics altered to "Hail! Hail! The Witch is Dead!." This started with the Witch's guard saying "Hail to Dorothy! The Wicked Witch is dead!" and dissolved to a huge celebration of the citizens of Emerald City singing the song as they accompany Dorothy and her friends to see the Wizard. Today, the film of this scene is also presumed lost and only a few stills survive along with a few seconds of footage used on several reissue trailers. The entire audio still exists and is included on the 2-CD Rhino Record deluxe edition of the film soundtrack.[47]

In addition, a brief reprise of Over the Rainbow was intended to be sung by Garland while Dorothy is trapped in the Witch's castle, but it was cut because it was too emotionally intense. The original soundtrack recording still exists, however, and was included as an extra in the 2005 DVD release.[48]

The songs were recorded in a studio before filming. Several of the recordings were completed while Buddy Ebsen was still with the cast. Therefore, while Ebsen had to be dropped from the cast due to illness from the aluminum powder makeup, his singing voice remained in the soundtrack. [as noted in the notes for the CD Deluxe Edition] In the group vocals of "We're Off to See the Wizard," his voice is easy to detect. Jack Haley spoke with a distinct Boston accent and thus did not pronounce the r in wizard. By contrast, Ebsen was a Midwesterner, like Judy Garland, and thus pronounced it. Of course, Haley rerecorded Ebsen's solo parts later.

Song list

- "Over the Rainbow" - Judy Garland as Dorothy Gale

- Munchkinland Sequence:

- "Come Out,..." - Billie Burke as Glinda and the Munchkins

- "It Really Was No Miracle" - Judy Garland as Dorothy, Billy Bletcher, and the Munchkins

- "We Thank You Very Sweetly" - Frank Cucksey and Joseph Koziel

- "Ding Dong the Witch Is Dead" - Billie Burke as Glinda (speaking) and the Munchkins

- "As Mayor of the Munchkin City"

- "As Coroner, I Must Aver"

- "Ding Dong the Witch Is Dead" (Reprise) - The Munchkins

- "The Lullaby League"

- "The Lollipop Guild"

- "We Welcome You to Munchkinland" - The Munchkins

- "Follow the Yellow Brick Road/You're Off to See the Wizard" - Judy Garland as Dorothy and the Munchkins

- "If I Only Had a Brain" - Ray Bolger as the Scarecrow and Judy Garland as Dorothy

- "We're Off to See the Wizard" - Judy Garland as Dorothy and Ray Bolger as the Scarecrow

- "If I Only Had a Heart" - Jack Haley as the Tin Man

- "We're Off to See the Wizard" (Reprise 1) - Judy Garland as Dorothy, Ray Bolger as the Scarecrow, and Buddy Ebsen as the Tin Man

- "If I Only Had the Nerve" - Bert Lahr as the Cowardly Lion, Jack Haley as the Tin Man, Ray Bolger as the Scarecrow, and Judy Garland as Dorothy

- "We're Off to See the Wizard" (Reprise 2) - Judy Garland as Dorothy, Ray Bolger as the Scarecrow, Buddy Ebsen as the Tin Man, and Bert Lahr as the Cowardly Lion

- "Optimistic Voices" - MGM Studio Chorus

- "The Merry Old Land of Oz" - Frank Morgan as Cabby, Judy Garland as Dorothy, Ray Bolger as Scarecrow, Jack Haley as the Tin Man and Bert Lahr as the Cowardly Lion

- "If I Were King of the Forest" - Bert Lahr as the Cowardly Lion, Judy Garland as Dorothy, Ray Bolger as the Scarecrow, and Jack Haley as the Tin Man

An arranged version of "Night on Bald Mountain" is played during the scene where the Scarecrow, the Tin Man, and the Cowardly Lion rescue Dorothy from the Wicked Witch of the West's castle.

Awards and honors

The film was nominated for several Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Visual Effects. In the Best Picture category, it lost to another MGM film, Gone with the Wind, another film directed by Victor Fleming. E.Y. Harburg and Harold Arlen won the award for Best Song (Over The Rainbow) and Best Original Music Score; composer Herbert Stothart received the Best Original Score Award. Garland received a special Academy Juvenile Award that year, for "Best Performances by a Juvenile" (the award was also for her role in the film version of Babes in Arms). The Wizard of Oz did not receive an Oscar for its special effects — that award went to the 1939 film version of The Rains Came. Additional nominations went to Cedric Gibbons and William A. Horning for Art Direction, and Hal Rosson for Cinematography (color), but both of those awards were won by Gone With the Wind. There was no award for makeup then, so Jack Dawn could not receive an award for his detailed makeup for the Oz fantasy characters.

In June 2008, AFI revealed its "Ten top Ten"—the best ten American films in ten genres—after polling over 1,500 film artists, critics and historians. The Wizard of Oz was acknowledged as the best film in the fantasy genre.[49][50]

- American Film Institute Lists

- AFI's 100 Years…100 Movies - #6

- AFI's 100 Years…100 Thrills - #43

- AFI's 100 Years…100 Heroes and Villains:

- The Wicked Witch of the West - #4 Villain

- AFI's 100 Years…100 Songs:

- "Over the Rainbow" - #1

- "Ding-Dong! The Witch Is Dead" - #82

- "If I Only Had A Brain/Heart/The Nerve" - Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years…100 Movie Quotes:

- "Toto, I've got a feeling we're not in Kansas anymore." - #4

- "There's no place like home." - #23

- "I'll get you, my pretty and your little dog, too!" - #99

- "Lions and tigers and bears, oh my!" - Nominated

- "I'm melting! Melting! Oh, what a world! What a world!" - Nominated

- "Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain!" - Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores - Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years of Musicals - #3

- AFI's 100 Years…100 Cheers - #26

- AFI's 100 Years…100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) - #10

- AFI's 10 Top 10 - #1 Fantasy film

The film is among the top ten of the BFI list of the 50 films you should see by the age of 14.[51]

Other noted honors

- 1999 Rolling Stone's 100 Maverick Movies ranked #20.[52]

- 1999 Entertainment Weekly's 100 Greatest Films ranked #32.[53]

- 2000 The Village Voice's 100 Best Films of the 20th Century ranked #14.[54]

- 2002 Sight & Sound's Greatest Film Poll of Directors ranked #41.[55]

- 2005 Total Film's 100 Greatest Films #83.[56]

- 2007 Total Film's 23 Weirdest Films ranked #1.[57]

- 2007 The Observer ranked the film's songs and music at the top of its list of 50 greatest film soundtracks.[58]

Sequels and reinterpretations

The Wizard of Oz was dramatized as a one-hour radio play on the December 25, 1950 broadcast of Lux Radio Theater, with Judy Garland reprising her earlier role. A sequel, the animated Journey Back to Oz, starring Liza Minnelli, daughter of Judy Garland, as Dorothy, was produced beginning in 1964 to commemorate the original film's 25th anniversary.[59] It also featured Margaret Hamilton, who previously played the Wicked Witch, as Aunt Em. The unfinished film lost financing early on and was not finished until 1972 when the producing studio, Filmation, had made enough profit from its television series to finish the film. It was released in the USA in 1974, and again in 1976 with additional live-action footage.

In 1975, the stage show The Wiz premiered on Broadway. It was an African American version of The Wizard of Oz reworked for the Broadway stage. It starred Stephanie Mills and other Broadway stars and earned Tony awards. The play's financing was handled by actor Geoffrey Holder. The play inspired revivals after it left the stage and a motion picture made in 1978, starring Diana Ross as Dorothy and Michael Jackson as the Scarecrow.

Disney made an unofficial sequel, Return to Oz, in 1985. Based mostly on the books Ozma of Oz and The Marvelous Land of Oz, it fared poorly with critics and in the box office, although it has since gone on to become a cult classic.[60]

In 1964, a one-hour animated cartoon, also called Return to Oz, was shown as an afternoon weekend special on NBC.

For the film's 56th anniversary, a stage show also entitled The Wizard of Oz was based upon the 1939 film and the book by L. Frank Baum. It toured from 1995–2008, except for 2004 (see The Wizard of Oz (1987 stage play)).

In 1995, Gregory Maguire published the book Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West (which was later adapted into the Tony Award winning Broadway musical Wicked), a back story to the film and novel that describes what happened before Dorothy dropped into Oz.

Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice wrote a musical based on the film, which is also titled The Wizard of Oz. The musical opened in 2011 at the West End's London Palladium. It features all of the songs from the film plus new songs written by Lloyd Webber and Rice. Lloyd Webber also found Danielle Hope to play Dorothy on the reality show, Over the Rainbow.

An unofficial telling of the events after The Wizard of Oz was filmed in 2010. The movie was titled After the Wizard and was written and directed by Hugh Gross. It is scheduled to be released on DVD on August 7th, 2012.

An animated film called Tom and Jerry and the Wizard of Oz was released in 2011 by Warner Home Video, incorporating Tom and Jerry into the story as Dorothy's "protectors".

A prequel to The Wizard of Oz is scheduled to be released in 2013. The working title is Oz: The Great and Powerful. It will be directed by Spider-Man's Sam Raimi and released by Disney. The film stars James Franco, Mila Kunis, and Michelle Williams.

Legacy

All of the film's stars except Frank Morgan, who died in 1949, lived long enough to see and enjoy at least some of the film's legendary reputation after it came to television. The last of the major players to die was Ray Bolger, in 1987. The day after his death, an editorial cartoon referenced the cultural impact of this film, portraying the Scarecrow running along the Yellow Brick Road to catch up with the other characters, as they all danced off into the sunset. Billie Burke died in 1970, Jack Haley in 1979, and Margaret Hamilton in 1985.

Despite his near-death experience with the aluminum-powder makeup, Buddy Ebsen outlived all his principal cast members by at least sixteen years, although his film career was damaged by the incident. Because of his illness, followed by his subsequent service in the Coast Guard, his career did not fully recover until the 1950s, when he began a string of popular film and TV series appearances, notably the Disney Davy Crockett films and the popular TV series The Beverly Hillbillies, that would continue into the 1980s. Although his lungs had presumably recovered from the effects of the powder makeup, he eventually died of complications from pneumonia on July 6, 2003 at the age of ninety-five.[61]

Director Victor Fleming, music arranger Herbert Stothart, screenwriter Edgar Allan Woolf, film editor Blanche Sewell, and actor Charley Grapewin (who played Uncle Henry) did not live to see the film's first telecast. By coincidence, Fleming, Stothart, Sewell and Morgan all died in 1949, which was also the year of the film's successful first re-release in movie theatres. Woolf had died the year before and Grapewin died in February 1956, nine months before the film's television premiere, and a few months after the film's second re-release. Costume designer Adrian died in September 1959, only three months before the highly successful second telecast of the film, the one that would persuade CBS to make it an annual tradition. The film's principal art director Cedric Gibbons died in July 1960, after the 1959 telecast, but only five months before the next TV showing on December 11, 1960.[62] And principal makeup artist Jack Dawn died in June 1961, six months after the film's third telecast. Bert Lahr died in December 1967. As the 1960s ended, Judy Garland joined them: she died in London on June 22, 1969 at the age of 47 from a drug overdose before a scheduled concert appearance.

Co-screenwriter Florence Ryerson died in 1965, after the film's seventh telecast, and principal screenwriter Noel Langley, who reportedly hated the changes that Ryerson and Edgar Allan Woolf had made to his version of the script,[63] but was later reconciled to them,[64] lived to see the film become a television institution. He died in 1980, months after the twenty-second telecast of the film. Oz songwriters E.Y. Harburg and Harold Arlen also lived to see the film become a television immortal, both of them also passing away in the 1980s, as did Oz director of photography Harold Rosson. A. Arnold Gillespie, the principal creator of the special effects which were so much a part of the film, died in 1978.

Cultural impact

Regarding the original Baum storybook, it has been said: "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is America's greatest and best-loved home grown fairytale. The first totally American fantasy for children, it is one of the most-read children's books . . . and despite its many particularly American attributes, including a wizard from Omaha, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz has universal appeal."[65]

The film also has been deemed "culturally significant" by the United States Library of Congress, which selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry in 1989. In June 2007, the film was listed on UNESCO's Memory of the World Register.[66] The film placed at number 86 on Bravo's 100 Scariest Movie Moments.[67] In 1977, Aljean Harmetz wrote The Making of The Wizard of Oz, a detailed description of the creation of the film based on interviews and research; it was updated in 1989.[68]

In a 2009 retrospective article about The Wizard of Oz, San Francisco Chronicle film critic and author Mick LaSalle declared that the film's "entire [Munchkinland] sequence, from Dorothy's arrival in Oz to her departure on the Yellow Brick Road, has to be one of the greatest in cinema history — a masterpiece of set design, costuming, choreography, music, lyrics, storytelling and sheer imagination.".[69]

Several quotes have made the AFI's 100 Years Top 100 Movies Quotes

- REDIRECT AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes

"Toto, I've got a feeling we're not in Kansas anymore." "There's no place like home." "I'll get you, my pretty, and your little dog too!"

Ruby slippers

Because of their iconic stature,[70] the ruby slippers worn by Judy Garland in The Wizard of Oz are now among the most treasured and valuable film memorabilia in movie history.[71] The silver slippers that Dorothy wore in the book series were changed to ruby to take advantage of the new Technicolor process. Gilbert Adrian, MGM's chief costume designer, was responsible for the final design. A number of pairs were made, though no one knows exactly how many.

After filming, the shoes were stored among the studio's extensive collection of costumes and faded from attention. They were found in the basement of MGM's wardrobe department during preparations for a mammoth auction in 1970. One pair was the highlight of the auction, going for a then unheard of $15,000 to an anonymous buyer, who apparently donated them to the Smithsonian in 1979. Four other pairs are known to exist; one sold for $666,000 at auction in 2000. A pair stolen from the Judy Garland Museum in Minnesota is still missing.[72] Another, differently styled pair not used in the film has been put up for auction with the rest of her collections by owner actress Debbie Reynolds.

Urban legends

An old urban legend claimed that, in the film, a Munchkin could be seen committing suicide (hanging by the neck from behind a prop tree and swinging back and forth) far away (left) in the background, while Dorothy, the Scarecrow, and the Tin Man are singing "We're Off to See the Wizard" and skipping down the Yellow Brick Road into the distance. The object in question is actually a bird borrowed from the Los Angeles Zoo, most likely a crane or an emu, one of several placed on the indoor set to give it a more realistic feel.[73][74][75][76][77][78]

The pairing of the 1973 Pink Floyd music album The Dark Side of the Moon with the visual portion of the film produces moments where they appear to correspond with each other in a music video-like experience. This juxtaposition has been called Dark Side of the Rainbow.[79]

Alleged impact upon the LGBT culture

The Wizard of Oz is alleged to have been identified as being of importance to the LGBT community, in part due to Judy Garland's starring role.[80] (According to the website activemusician.com, during a press conference in San Francisco in the 1960s, a reporter asked Garland if she was aware of her loyal gay following. "I couldn't care less," she said. "I sing to people.")

Attempts have been made to determine the film's impact on LGBT-identified persons: editors Corey K. Creekmur and Alexander Doty, in their introduction to Out in Culture: Gay, Lesbian and Queer Essays on Popular Culture (1995, Duke University Press), write that the film's gay resonance and interpretations depends entirely upon camp.[81] Some have attempted a more serious interpretation of the film: for example, Cassell's Encyclopedia of Queer Myth, Symbol and Spirit: Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Lore quotes therapist Robert Hopcke as saying that the dreary reality of Kansas implies the presence of homophobia and is contrasted with the colorful and accepting land of Oz."[80]; they state that when shown in gay venues, the film is "transformed into a rite celebrating acceptance and community.[80] Queer theorists have attempted to draw parallels between LGBT people and characters in the film, specifically pointing to the characters' double lives and Dorothy's longing "for a world in which her inner desires can be expressed freely and fully."[80]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Fricke, John (1989). The Wizard of Oz: The Official 50th Anniversary Pictorial History. New York: Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-51446-2.

- ^ Note: All actors share equal billing, the Singer Midgets are listed in the credits as "The Munchkins"

- ^ a b TCM Notes on The Wizard of Oz. Retrieved on January 8, 2011.

- ^ Library Of Congress (December 15, 2010). "To See The Wizard Oz on Stage and Film". Library Of Congress. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ Jahangir, Rumeana (March 17, 2009). "Secrets of the Wizard of Oz". BBC. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

- ^ Rhodes, Jesse (January 2009). "There's No Place Like Home". Smithsonian. Vol. 39, no. 10. p. 25.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)

This short article also speaks to the donation of a pair to the Smithsonian and to auctions of pairs. - ^ http://www.amazon.com/dp/0688166776/ref=rdr_ext_tmb

- ^ Credited as "Toto" in the film

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0032138/soundtrack

- ^ [1]

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0909930/

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0704638/

- ^ a b c d e The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, the Making of a Movie Classic (1990). CBS Television, narrated by Angela Lansbury. Coproduced by John Fricke and Aljean Harmetz.

- ^ a b Aljean Harmetz (2004). The Making of The Wizard of Oz. Hyperion. ISBN 0-7868-8352-9. See Chapter "Special Effets".

- ^ Clarke, Gerald (2001). Get Happy: The Life of Judy Garland. Delta. p. 94. ISBN 0-385-33515-6.

- ^ Fricke, John (1986). The Wizard of Oz: The Official 50th Anniversary Pictorial History. New York, NY: Warner Books, Inc. p. 18. ISBN 0-446-51446-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Warner Bros. "Wizard of Oz Timeline". Warnerbros.com. Archived from the original on September 7, 2007. Retrieved September 10, 2007.

- ^ Democracy Now article 25, November 2004.

- ^ Fordin, Hugh (1976). World of Entertainment. City: Avon Books (Mm). ISBN 978-0-380-00754-7.

- ^ "Hollywood Reporter, Oct. 20, 2005".

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) [dead link] - ^ The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, the Making of a Movie Classic. CBS Television, 1990, narrated by Angela Lansbury. Co-produced by John Fricke and Aljean Harmetz.

- ^ Cemetery Guide, Hollywood Remains to Be Seen, Mark Masek.

- ^ Fricke, John and Scarfone and William Stillman. The Wizard of Oz: The Official 50th Anniversary Pictorial History, Warner Books, 1989

- ^ Hearn, Michael Patrick. Keynote address. The International Wizard of Oz Club Centennial convention. Indiana University, August 2000.

- ^ Smalling, Allen (1989). The Making of the Wizard of Oz: Movie Magic and Studio Power in the Prime of MGM. Hyperion. ISBN [[Special:BookSources/100786883529 |100786883529 [[Category:Articles with invalid ISBNs]]]].

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ The Wizard of Oz 70th Anniversary News[dead link]

- ^ The Making of the Wizard of Oz - Movie Magic and Studio Power in the Prime of MGM - and the Miracle of Production #1060, 10th Edition, Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc., 1989.

- ^ Jim's "Wizard of Oz" Website Directory. ""The Wizard of Oz"...A Movie Timeline". geocities.com. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved September 10, 2007.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Williams, Scott (July 21, 2009). "Hello, yellow brick road". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

John Fricke, a historian who has authored books about "The Wizard of Oz," said MGM executives arranged advance screenings in a handful of small communities to find out how audiences would respond to the musical adventure, which cost nearly $3 million to produce. Fricke said he believes the first showings were on Aug. 11, 1939 - one day before Oconomowoc's preview - in Cape Cod, Mass., and in another southeastern Wisconsin community: Kenosha.

- ^ a b Cisar, Katjusa (August 18, 2009). "No Place Like Home: 'Wizard of Oz' premiered here 70 years ago". Madison.com. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

Oconomowoc's Strand Theatre was one of three small-town movie theaters across the country where "Oz" premiered in the days prior to its official Hollywood opening on Aug. 15, 1939...It's possible that one of the other two test sites - Kenosha and a town in Massachusetts - screened the film a day earlier, but Oconomowoc is the only one to lay claim and embrace the world premiere as its own.

- ^ "Beloved movie's premiere was far from L.A. limelight". Wisconsin State Journal. August 12, 2009. p. a2.

- ^ a b Nugent, Frank S. (August 18, 1939). "The Wizard of Oz, Produced by the Wizards of Hollywood, Works Its Magic on the Capitol's Screen". [[]]. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ "The Wizard of Oz garners full approval at Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ^ Cruz, Gilbert (August 30, 2010). "The Wizard of Oz". Time. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ "THE WIZARD OF OZ (1939, U.S.)". Kiddiematinee.com. November 3, 1956. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ^ The Wizard of Oz (2002 re-issue) @ Box Office Mojo

- ^ The Wizard of Oz 70th Anniversary Event Returns to More Than 300 Movie Theaters Nationwide for a Command Performance on November 17th

- ^ The Wizard of Oz (1939) - TV schedule

- ^ "Ford Star Jubilee" The Wizard of Oz (1956)

- ^ Red Skelton - Other works

- ^ Richard Boone (I) - Other works

- ^ Dick Van Dyke - Other works

- ^ Danny Kaye - Other works

- ^ "MGM/CBS Home Video ad". Billboard Magazine (Nov 22, 1980). Billboard. 1980. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ^ Julien WILK (February 28, 2010). "LaserDisc Database — Search — wizard of oz". Lddb.com. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ^ "Off To See The Wizards: HDD Gets An In Depth Look at the Restoration of 'The Wizard of Oz' (UPDATED — Before and After Pics!)". Highdefdigest.com. September 11, 2009. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ^ The Wizard Of Oz: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack — The Deluxe Edition, 2-CD set, original recording remastered, Rhino Records # 71964 (July 18, 1995)

- ^ Warner Bros. 2005 The Wizard of Oz Deluxe DVD edition, program notes and audio extras.

- ^ American Film Institute (June 17, 2008). "AFI Crowns Top 10 Films in 10 Classic Genres". ComingSoon.net. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ "Top 10 Fantasy". American Film Institute. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ "The 50 films you should see by the age of 14". Daily Mail. London. July 20, 2005. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- ^ "100 Maverick Movies in 100 Years from Rolling Stone". Filmsite.org. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Movies of All Time by Entertainment Weekly". Filmsite.org. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ^ "100 Best Films — Village Voice". Filmsite.org. January 4, 2000. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ^ "Sight & Sound | Top Ten Poll 2002 - The rest of the directors' list". BFI. September 5, 2006. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ^ Total Film (October 24, 2005). "Film news Who is the greatest?". TotalFilm.com. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ^ "Total Film's 23 Weirdest Films of All Time on Lists of Bests". Listsofbests.com. April 6, 2007. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ^ The Observer Music Monthly (March 18, 2007). "The 50 Greatest Film Soundtracks". London: Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved September 10, 2007.

- ^ The Wizard of Oz Production Timeline

- ^ Wieselman, Jarett (September 24, 2009). ""Return To Oz" Still Haunts Me". www.nypost.com. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ newsfromme.com (2003). "Oz Stuff". povonline. Retrieved September 10, 2007.

- ^ Brainerd (Minnesota, USA) Daily Dispatch, Dec. 9, 1960, accessed through newspaperarchive.com on March 12, 2009

- ^ "The Making of the Wizard of Oz: Movie Magic and Studio Power in the Prime of MGM (9780786883523): Aljean Harmetz: Books". Amazon.com. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ^ ttp://www.amazon.com/Making-Wizard-Oz-Movie-Studio/dp/0786883529/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1316984781&sr=1-1

- ^ "The Wizard of Oz: An American Fairy Tale".

- ^ "UNESCO chooses The Wizard of Oz as USA's Memory of the World". UNESCO. Retrieved March 21, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Bravotv.com. "The 100 Scariest Movie Moments". Bravotv.com. Archived from the original on October 30, 2007. Retrieved January 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ ISBN 0-7868-8352-9

- ^ LaSalle, Mick (October 30, 2009). "Thoughts on 'The Wizard of Oz' at 70". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ^ Dwight Blocker Bowers (January 2010). "The Ruby Slippers: Inventing an American Icon". The Lemelson Center. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ^ Monte Burke (December 3, 2008). "Inside The Search For Dorothy's Slippers". Forbes. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Thomas, Rhys (1989). The Ruby Slippers of Oz. Tale Weaver Pub. ISBN 0-942139-09-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Doolittle, Leslie (October 29, 1996). "Really Most Sincerely, Still a Munchkin". The Orlando Sentinel.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "article: "Wizard of Oz" Munchkin Suicide: Hanging Munchkin". Snopes.com. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ^ "The "Hanged Man"". Retrieved June 4, 2009.

- ^ "What's the myth of the hanging Munchkin?". BBC News. August 9, 2006. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Fine, Marshall (April 26, 1990). "Defusing the Rumor of 'Oz'". Gannett News Service.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Malcolm, Paul (December 20, 1996). "L. Frank Baum's Silent Film Collection". LA Weekly. p. 90.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "DSOTR". Retrieved June 4, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d Caonner & Sparks (1998), p. 349 Conner, Randy P. (1998). Cassell's Encyclopedia of Queer Myth, Symbol and Spirit. UK: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-70423-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Green (1997), p. 404 Green, Thomas A. (1997). Folklore: an encyclopedia of beliefs, customs, tales, music and art. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-87436-986-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

References

Bibliography

- Memories of a Munchkin: An Illustrated Walk Down the Yellow Brick Road by Meinhardt Raabe and Daniel Kinske (Back Stage Books, 2005) ISBN 0-8230-9193-7

- Ruby Slippers of Oz, The by Rhys Thomas (Tale Weaver, 1989) ISBN 0-942139-09-7 ISBN 978-0-942139-09-9

- Wizardry of Oz, The: The Artistry And Magic of The 1939 MGM Classic — Revised and Expanded by Jay Scarfone and William Stillman (Applause Books, 2004) ISBN 0-517-20333-2 ISBN 978-0-517-20333-0

- The Munchkins of Oz by Stephen Cox (Cumberland House, 1996) ISBN 1-58182-269-3 ISBN 978-1-58182-269-4

- "Did these stories really happen?" by Michelle Bernier (Createspace, 2010) ISBN 1-4505-8536-1

External links

- Official website

- Wizard of Oz Film Site With Oz Community Interviews

- The Wizard of Oz at the TCM Movie Database

- The Wizard of Oz at IMDb

- The Wizard of Oz at AllMovie

- The Wizard of Oz at Box Office Mojo

- The Wizard of Oz at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Wizard of Oz on Oz Wiki, an external wiki

- the Judy Room (Oz Section)

- Script before cuts

- The Wizard of Oz on Lux Radio Theater: December 25, 1950

- Articles with dead external links from December 2008

- Use mdy dates from September 2010

- 1939 films

- The Wizard of Oz (1939 film)

- 1930s adventure films

- American coming-of-age films

- American children's fantasy films

- American fantasy adventure films

- American LGBT-related films

- Best Song Academy Award winners

- Best Original Music Score Academy Award winners

- Black-and-white films

- Children's fantasy films

- Dreaming and fiction

- English-language films

- Epic films

- Fantasy adventure films

- Films based on children's books

- Films based on fantasy novels

- Films based on novels

- Films directed by King Vidor

- Films directed by Victor Fleming

- Films featuring anthropomorphic characters

- Films set in Kansas

- Films set in the 1880s

- Films shot in Technicolor

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films

- Memory of the World Register

- Musicals by Harold Arlen

- Musicals by Yip Harburg

- Musical fantasy films