Magna Carta

| Magna Carta | |

|---|---|

One of only four surviving exemplifications of the 1215 text, Cotton MS. Augustus II. 106, property of the British Library | |

| Created | 1215 |

| Location | Various copies |

| Author(s) | sant baba jarnail singh ji khalsa bhindrawala |

| Part of the Politics series |

| Monarchy |

|---|

|

|

|

Magna Carta (Latin for Great Charter),[1] also called Magna Carta Libertatum or The Great Charter of the Liberties of England, is an Angevin charter originally issued in Latin in the year 1215.

Magna Carta was the first document forced onto a King of England by a group of his subjects, the feudal barons, in an attempt to limit his powers by law and protect their privileges.

The charter was an important part of the extensive historical process that led to the rule of constitutional law in the English speaking world. Magna Carta was important in the colonization of American colonies as England's legal system was used as a model for many of the colonies as they were developing their own legal systems.

The 1215 charter required King John of England to proclaim certain liberties and accept that his will was not arbitrary—for example by explicitly accepting that no "freeman" (in the sense of non-serf) could be punished except through the law of the land, a right that still exists.

It was preceded and directly influenced by the Charter of Liberties in 1100, in which King Henry I had specified particular areas wherein his powers would be limited.

It was translated into vernacular French as early as 1219,[2] and reissued later in the 13th century in modified versions. The later versions excluded the most direct challenges to the monarch's authority that had been present in the 1215 charter. The charter first passed into law in 1225; the 1297 version, with the long title (originally in Latin) "The Great Charter of the Liberties of England, and of the Liberties of the Forest," still remains on the statute books of England and Wales.

Despite its recognised importance, by the second half of the 19th century nearly all of its clauses had been repealed in their original form. Three clauses currently remain part of the law of England and Wales, however, and it is generally considered part of the uncodified constitution. Lord Denning described it as "the greatest constitutional document of all times – the foundation of the freedom of the individual against the arbitrary authority of the despot".[3] In a 2005 speech, Lord Woolf described it as "first of a series of instruments that now are recognised as having a special constitutional status",[4] the others being the Habeas Corpus Act (1679), the Petition of Right (1628), the Bill of Rights (1689), and the Act of Settlement (1701).

It was Magna Carta, over other early concessions by the monarch, which survived to become a "sacred text".[5] In practice, Magna Carta in the medieval period did not generally limit the power of kings, but by the time of the English Civil War it had become an important symbol for those who wished to show that the King was bound by the law. It influenced the early settlers in New England[6] and inspired later constitutional documents, including the United States Constitution.[7]

Great Charter of 1215

Rebellion and creation of the document

Some barons began to conspire against King John in 1209 and 1212; promises made to the northern barons and John's submission to universal rule of the papacy in 1213 delayed a French invasion.[8] Over the course of his reign a combination of higher taxes, unsuccessful wars that resulted in the loss of English barons' titled possessions in Normandy following the Battle of Bouvines (1214), and the conflict with Pope Innocent III (ending with John's submission in 1213) had made King John unpopular with many of his barons.

In 1215 some of the most important barons engaged in open rebellion against their king. Such rebellions were not particularly unusual in this period. Every king since William the Conqueror had faced rebellions. What was unusual about the 1215 rebellion was that the rebels had no obvious replacement for John; in every previous case there had been an alternative monarch around whom the rebellion could rally. Arthur of Brittany would have been a possibility, if he had not disappeared years earlier while John's prisoner (and widely believed to have been murdered by John). The next closest alternative was Prince Louis of France, but as the husband of Henry II's granddaughter, his claim was tenuous, and the English had been at war with the French for thirty years. Instead of a claimant to the throne, the barons decided to base their rebellion around John's oppressive government. In January 1215, the barons made an oath that they would "stand fast for the liberty of the church and the realm", and they demanded that King John confirm the Charter of Liberties, from what they viewed as a golden age.[9]

John attempted to use the lengthy negotiations to avoid a confrontation while he waited for support from the Pope and hired mercenaries, adopting various measures to weaken the rebels' position and improve his own, including taking the cross as a crusader in March 1215 (which the Pope applauded but most other observers considered insincere), demanding a new oath of allegiance, and confirming London's city charter in May 1215.[10] During negotiations between January and June 1215, a document was produced, which historians have termed 'The Unknown Charter of Liberties',[11] seven of the articles of which later appeared in the 'Articles of the Barons' and the Runnymede Charter.[12] In May, King John offered to submit issues to a committee of arbitration with Pope Innocent III as the supreme arbiter,[13] but the barons continued in their defiance. With the support of Prince Louis the French Heir and of King Alexander II of the Scots, they entered London in force on 10 June 1215,[14] with the city showing its sympathy with their cause by opening its gates to them. They, and many of the moderates not in overt rebellion, forced King John to agree to a document later known as the 'Articles of the Barons', to which his Great Seal was attached in the meadow at Runnymede on 15 June 1215. In return, the barons renewed their oaths of fealty to King John on 19 June 1215, which is when the document Magna Carta was created.

In return for King John's submission to his papal and universal authority, Innocent III declared Magna Carta annulled, though many English Barons did not accept this action.

The contemporary, but unreliable[15] chronicler, Roger of Wendover, recorded the events in his Flores Historiarum.[16] A formal document to record the agreement was created by the royal chancery on 15 July: this was the original Magna Carta, though it was not known by that name at the time. An unknown number of copies of it were sent out to officials, such as royal sheriffs and bishops.

Clause 61

The 1215 document contained a large section that is now called clause 61 (the original document was not actually divided into clauses). This section established a committee of 25 barons who could at any time meet and overrule the will of the King if he defied the provisions of the Charter, seizing his castles and possessions if it was considered necessary.[17] This was based on a medieval legal practice known as distraint, but it was the first time it had been applied to a monarch.

Distrust between the two sides was overwhelming. What the barons really sought was the overthrow of the King; the demand for a charter was a "mere subterfuge."[18] Clause 61 was a serious challenge to John's authority as a ruling monarch. He renounced it as soon as the barons left London; Pope Innocent III also annulled the "shameful and demeaning agreement, forced upon the King by violence and fear." He rejected any call for restraints on the King, saying it impaired John's dignity. He saw it as an affront to the Church's authority over the King and the 'papal territories' of England and Ireland, and he released John from his oath to obey it. The rebels knew that King John could never be restrained by Magna Carta and so they sought a new King.[19]

England was plunged into a civil war, known as the First Barons' War. With the failure of Magna Carta to achieve peace or restrain John, the barons reverted to the more traditional type of rebellion by trying to replace the monarch they disliked with an alternative. In a measure of some desperation, despite the tenuousness of his claim and despite the fact that he was French, they offered the crown of England to Prince Louis of France.[20]

As a means of preventing war, Magna Carta was a failure, rejected by most of the barons,[21] and was legally valid for no more than three months.[22] The death of King John in 1216, however, secured the future of Magna Carta.[23]

List of participants

Barons, Bishops and Abbots who were party to Magna Carta.[24]

Others

- Llywelyn the Great. Also the other Welsh Princes

- Master Pandulff, subdeacon and member of the Papal Household

- Brother Aymeric, Master of the Knights Templar in England

- Alexander II of Scotland

Magna Carta of Chester

The Runnymede Charter of Liberties did not apply to Chester, which at the time was a separate feudal domain. Earl Ranulf granted his own Magna Carta.[25] Some of its articles were similar to the Runnymede Charter.[26]

Great Charter 1216–1369

The Charter 1216

King John's nine-year-old son Henry was crowned King of England in Gloucester Abbey, though much of England lay under the usurper Prince Louis. The papal legate Guala Bicchieri declared the struggle against Louis and the Barons a holy war,[27] and the loyalists led by William Marshal rallied around the new King. Earl Ranulf of Chester left the Regency to Marshall. Marshall and Guala issued a Charter of Liberties, based on the Runnymede Charter, in the King's name on 12 November 1216 as a Royal concession, in an attempt to undermine the rebels.[28]

The Charter differed from that of 1215 in only having 42 as compared to 61 clauses; most notably the infamous article 61 of the Runnymede Charter was removed. The Charter was also issued separately for Ireland.

The Charters 1217: origins of the name Magna Carta

Following the end of the First Barons War and the Treaty of Lambeth, the Charter of Liberties (carta libertatum) was issued again in the manner of 1216, again amended and issued separately for Ireland. The 42 clauses of the 1216 issue were expanded to 47.

Significantly, a fragment of the original charter would be expanded with new material to form a complementary charter, the Charter of the Forest; the two Charters would thereafter be linked. Magna carta libertatum was then used by scribes to differentiate the larger and more important charter of common liberties from the Forest Charter.[29] The term was used retrospectively to describe the previous Charters, with what had previously been described as carta libertatum becoming known simply as Magna Carta.

The Great Charter 1225

Having reached the age of majority, King Henry III was called upon to confirm the Charters. Henry reissued Magna Carta in a shorter version with only 37 articles, as a concession of liberties in return for a fifteenth part of moveable goods.[6] This was the first version of the Charter to enter English law.[30] The Charter of Liberties included a new statement that the Charter had been issued spontaneously and of the King's own free will. In 1227, Henry III declared all future charters had to be issued under his own seal and state under what warrant they were claimed; this proclamation questioned the validity of all previous acts done in his name or his predecessors.[31] It was not until 1237, and the carta parva, that both of the 1225 Charters were confirmed and granted in perpetuity.[32]

The Great Charter 1297: Statute

Edward I of England reissued the Charters of 1225 in 1297 in return for a new tax.[33] "Constitutionally, the Magna Carta of Edward I is the most important".[34] This version remains in Statute today (albeit with most articles now repealed—see below).[35][36]

Confirmatio Cartarum and Articuli super Cartas

The Confirmatio Cartarum (Confirmation of Charters) was issued by Edward I in 1297, and was similar to the parva carta issued by Henry III in 1237. In the Confirmation, Edward reaffirmed Magna Carta and the Forest Charter[37] as a concession for tax money. As part of the Remonstrances the nobles sought to add another document the De Tallagio to the Charters but without success.[38] The principle of taxation by consent was reinforced, however the precise manner of that consent was not laid down.[39]

Pope Clement V annulled the Confirmatio Cartarum in 1305.[40]

As part of the reconfirmation of the Charters in 1300 an additional document was granted, the Articuli super Cartas (The Articles upon the Charters). It was composed of 20 articles and sought in part to deal with the problem of enforcing the Charters.[41] In 1305 Edward I took Clement V's Papal bull annulling the Confirmatio Cartarum to effectively apply to the Articuli super Cartas though it was not specifically mentioned.[42]

Six Statutes

During the reign of Edward III, six measures were passed between 1331 and 1369, which were later known as the Six Statutes. They sought to clarify certain parts of the Charters. In particular, the third statute, of 1354, redefined clause 29, with free man becoming no man, of whatever estate or condition he may be, and introduced the phrase due process of law for lawful judgement of his peers or the law of the land.[43]

Later history

Reconfirmations

The impermanence of the Charter required successive generations to petition the King to reconfirm his Charter, and hopefully abide by it. Between the 13th and 15th centuries Magna Carta would have a history of being reconfirmed, 32 times according to Sir Edward Coke, but possibly as many as 45 times.[44] The Charter was last confirmed in 1423 by Henry VI.

Repeal of articles

The repeal of clause 26 in 1829, by the Offences against the Person Act 1828 (9 Geo. 4 c. 31 s. 1),[45] was the first time a clause of Magna Carta was repealed. With the document's perceived inviolability broken,[citation needed] in the next 140 years nearly the whole charter was repealed, leaving just Clauses 1, 9, and 29 still in force after 1969. Most of it was repealed in England and Wales by the Statute Law Revision Act 1863, and in Ireland by the Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872.[45]

| Magna Carta 1225 Clause | Runnymede Charter Clause | Date Repealed |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | I | extant |

| 2 | II | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| 3 | III | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| 4 | IV | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| 5 | V | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| 6 | VI | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| 7 | VII, VIII | Administration of Estates Act 1925, Administration of Estates Act (Northern Ireland) 1955 and Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1969 |

| 8 | IX | Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1969 |

| 9 | XIII | extant |

| 10 | XVI | Statute Law Revision Act 1948 |

| 11 | XVII | Civil Procedure Acts Repeal Act 1879 |

| 12 | XVIII | Civil Procedure Acts Repeal Act 1879 |

| 13 | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 | |

| 14 | XX, XXI, XXII | Criminal Law Act 1967 and Criminal Law Act (Northern Ireland) 1967 |

| 15 | XXIII | Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1969 |

| 16 | XXXXVII | Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1969 |

| 17 | XXIV | Statute Law Revision Act 1892 |

| 18 | XXVI | Crown Proceedings Act 1947 |

| 19 | XXVIII | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| 20 | XIX | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| 21 | XXX, XXXI | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| 22 | XXXII | Statute Law Revision Act 1948 |

| 23 | XXXIII | Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1969 |

| 24 | XXXIV | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| 25 | XXXV | Statute Law Revision Act 1948 |

| 26 | XXXVI | Offences against the Person Act 1828 and Offences against the Person (Ireland) Act 1829 |

| 27 | XXXVII | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| 28 | XXXVIII | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| 29 | XXXIX,XXXX | extant |

| 30 | XXXXI | Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1969 |

| 31 | XXXXIII | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| 32 | Statute Law Revision Act 1887 | |

| 33 | XXXXVI | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| 34 | LIV | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| 35 | Sheriffs Act 1887 | |

| 36 | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 | |

| 37 | LX | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

Content

Magna Carta was originally written in Latin. A large part of the Charter at Runnymede was copied, nearly word for word, from the Charter of Liberties of Henry I, issued when Henry became king in 1100, in which he said he would respect certain rights of the Church and the barons, for example not forcing heirs to purchase their inheritances.

As the Charter went through various issues many of the clauses included in the Runnymede charter were removed. Some clauses would form a supplementary Charter in 1217, the Charter of the Forest.

It is worth emphasising that the 1215 charter was not numbered and was not divided into paragraphs or separate clauses. The numbering system used today was created by Sir William Blackstone in 1759,[46] and therefore should not be used to draw any conclusions regarding the intentions of the original creators of the charter.

Clauses still in force

The clauses of the 1297 Magna Carta still on statute are:

- Clause 1, the freedom of the English Church

- Clause 9 (clause 13 in the 1215 charter), the "ancient liberties" of the City of London

- Clause 29 (clause 39 in the 1215 charter), a right to due process

- 1. FIRST, We have granted to God, and by this our present Charter have confirmed, for Us and our Heirs for ever, that the Church of England shall be free, and shall have all her whole Rights and Liberties inviolable. We have granted also, and given to all the Freemen of our Realm, for Us and our Heirs for ever, these Liberties under-written, to have and to hold to them and their Heirs, of Us and our Heirs for ever.

- 9. THE City of London shall have all the old Liberties and Customs which it hath been used to have. Moreover We will and grant, that all other Cities, Boroughs, Towns, and the Barons of the Five Ports, as with all other Ports, shall have all their Liberties and free Customs.

- 29. NO Freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or be disseised of his Freehold, or Liberties, or free Customs, or be outlawed, or exiled, or any other wise destroyed; nor will We not pass upon him, nor condemn him, but by lawful judgment of his Peers, or by the Law of the land. We will sell to no man, we will not deny or defer to any man either Justice or Right.[45]

The last sentence of Clause 29 deals with the administration of justice. “We will sell to no man” were intended to abolish the fines demanded by King John in order to obtain justice. “Will not deny” referred to the stopping of suits and the denial of writs. “Delay to any man” meant the delays caused either by the counter-fines of defendants, or by the prerogative of the King.[47] There is debate about the gradual erosion of the remaining provisions of Magna Carta, particularly by encroachment from the European Union - for example the effects on due process of the Charter of Fundamental Rights.[48]

Clauses in Runnymede Charter but not in later Charters

- Clauses 10 and 11 related to money lending and Jews in England. Jews were particularly involved in money lending because Christian teachings on usury did not apply to them. Clause 10 said that children would not pay interest on a debt they had inherited while they were under age. Clause 11 said that the widow and children should be provided for before paying an inherited debt. The charter concludes this section with the words "Debts owing to other than Jews shall be dealt with likewise", so it is debatable to what extent the Jews were being singled out by these clauses.

- Clauses 12 and 14 state that taxes (in the language of the time, "scutage or aid") can only be levied and assessed by the common counsel of the realm. See Challenges to the King's power for more detail.

- Clause 15 stated that the King would not grant anyone the right to take an aid (i.e. money) from his free men

- Clauses 25 and 26 dealt with debt and taxes

- Clause 27 dealt with intestacy.

- Clause 42 stated that it was lawful for subjects to leave the kingdom without prejudicing their allegiance (except for outlaws and during war)

- Clause 45 said that the King should only appoint as "justices, constables, sheriffs, or bailiffs" those who knew the law and would keep it well. In the United States, the Supreme Court of California interpreted clause 45 in 1974 as establishing a requirement at common law that a defendant faced with the potential of incarceration is entitled to a trial overseen by a legally trained judge.[49]

- Clause 48 stated that all evil customs connected with forests were to be abolished

- Clause 49 provided for the return of hostages held by the King. (John held hostages from the families of important nobles he wished to ensure remained loyal, as other English monarchs had before him.)

- Clause 50 stated that no member of the d'Athée family could be a royal officer.

- Clause 51 called for all foreign knights and mercenaries to leave the realm.

- Clause 52 dealt with restoration of those "disseised" (i.e. those dispossessed of property. See (for example) Assize of novel disseisin )

- Clause 53 was similar to 52 but relating to forests

- Clause 55 regarded remittance of unjust fines

- Clauses 57 concerned restoration of disseised Welshmen

- Clauses 58 and 59 provided for the return of Welsh and Scottish hostages

- Clauses 61 provided for the application and observation of the Charter by twenty-five of the rebellious barons. See Challenges to the King's power for more on clause 61.

- Clause 62 pardoned those who had rebelled against the king

- Clause 63 said that the charter was binding on King John and his heirs. However this version of the charter was renounced by John, with the support of the Pope. The smaller 1225/1297 charters (which actually became law) contain similar text, stating that the monarch and their heirs would not seek to infringe or damage the liberties in the charter, and that the charter is to be observed "in perpetuity".

Challenges to the King's power

Clauses 12 and 14 of the 1215 charter state that the king will accept the "common counsel of our realm" when levying and assessing an aid or a scutage. Clause 14 goes into detail about how exactly the archbishops, bishops, abbots, earls and greater barons should be consulted. These clauses effectively meant that the monarch had to ask before raising new taxes. The later charters merely said that "Scutage furthermore is to be taken as it used to be", although in practice the convention arose after Magna Carta that Parliament would be consulted by the monarch before raising new taxes.

Clause 61 of the 1215 charter states: "The barons shall choose any twenty-five barons of the realm they wish, who with all their might are to observe, maintain and cause to be observed the peace and liberties which we have granted and confirmed to them by this our present charter". The clause goes on to say that if the king does not keep to the charter, the twenty five barons shall seize "castles, lands and possessions... until, in their judgement, amends have been made". "Anyone in the land" would be permitted by the king to swear an oath to the twenty five to obey them in these matters, and the king was in fact supposed to order people to do so even if they didn't want to swear an oath to the twenty five barons.

The barons were trying to stop John going back on his word after agreeing to the charter, but if those who rebelled against him were able to choose a group who would have the power to seize his castles if they thought it necessary, "then the king had in effect been dethroned". No king would have agreed to this except as a manoeuvre to gain time, and the inclusion of this clause destroyed any chance of the original Magna Carta keeping the peace in the long term.[50]

Clause 61 was removed from all later versions of the charter. Forty years later, after another confrontation between king and barons, the Provisions of Oxford forced on the king a council of twenty four members, 12 selected by the crown, 12 by the barons, which would then elect a king's council of fifteen members; this however was also annulled when Henry III finally won that power struggle.

Clauses in Runnymede Charter and in 1216/1217 Charter but not in 1225/1297 Charter

- Clauses 2 to 3 refer to feudal relief, specifically the regulation of the charging of excessive relief, in effect a form of "succession duty" or "death duty" payable by an heir.

- Clauses 4 to 5 refer to the duties of wardship, specifically forbidding the practice of the over-exploitation of a ward's property by his warder (or guardian).

- Clause 6 refers to a warder's power over the marriage of his ward. He was forbidden from forcing a marriage to a partner of lower social standing (possibly therefore to one such who may have been willing to pay a higher price for it).

- Clause 7 refers to the rights of a widow to receive promptly her dowry and inheritance.

- Clause 8 stated that a widow could not be compelled to marry.

- Clause 9 stated that a debtor should not have his lands seized as long as he had other means to pay the debt.

- Clause 16 was regarding a knight's fee.

- Clauses 17 to 19 allowed for a fixed law court, which became the chancellery, and defined the scope and frequency of county assizes.

- Clause 44 (1216 only) relating to forest law

- Clause 56 (1216 only) relating to disseised Welshmen

Clauses in Runnymede Charter and 1225/1297 Charter but since repealed

All of the remaining parts of the 1215 charter appear substantially unchanged in the 1225/1297 charter, which became law and is still on the statute book. All except the three clauses still in force today were eventually repealed however, most in the 19th century. Many provisions have no bearing in the world today, since they deal with feudal liberties. Some clauses remained relevant but were replaced by later legislation that provided similar rights. Using the 1215 clause numbers:

- Clause 20 stated that fines ("amercements", in the language of the day), should be proportionate to the offence, but even for a serious offence the fine should not be so heavy as to deprive a man of his livelihood. No fines should be imposed except by the oath of honest local men.

- Clause 21 stated that earls and barons should only be fined by their peers, i.e. other earls and barons. Until 1948 this meant that members of the House of Lords had the right to a criminal trial in the House of Lords at first instance.

- Clause 22 stated that fines should not be influenced by ecclesiastical property in clergy trials.

- Clause 23 provided that no town or person should be forced to build a bridge across a river.

- Clause 24 stated that crown officials (such as sheriffs) must not try a crime in place of a judge.

- Clauses 28 to 32 stated that no royal officer might take any commodity such as grain, wood or transport without payment or consent or force a knight to pay for something the knight could do himself, and that the king must return any lands confiscated from a felon within a year and a day to the felon's feudal lord ("the lords of the fees concerned").

- Clause 33 required the removal of all fish weirs.

- Clause 34 forbade repossession without a "writ precipe".

- Clause 35 set out a list of standard measures

- Clause 36 stated that writs for loss of life or limb were to be free

- Clause 37 concerns inheritance when a "fee-farm" (fee as in knight's fee) was involved.

- Clause 38 stated that no-one could be put on trial based solely on the unsupported word of an official.

- Clause 40 disallowed the selling of justice, or its denial or delay.

- Clauses 41 and 42 guaranteed the safety and right of entry and exit of foreign merchants.

- Clause 43 gave special provision for tax on reverted estates

- Clause 46 provided for the guardianship of monasteries.

- Clauses 47 and 48 abolished most of Forest Law (these clauses were split out of the main charter and formed part of a separate charter, the Charter of the Forest).[51]

- Clause 54 said that no man may be imprisoned on the testimony of a woman except on the death of her husband.

Clauses in the 1225/1297 Charter but not in the Runnymede Charter

A few clauses are in the 1225/1297 charter but not in the 1215 charter. These have also since been repealed. Using the 1297 clause numbers:

- Clause 13 concerned the Assize of darrein presentment.

- Clause 32 said that a free man should not give away or sell so much of his land that he would not be able to meet his feudal obligations to his lord.

- Clause 35 concerned the county court, the frankpledge and tithes.

- Clause 36 said that it was not permitted to give land to a religious house and then receive it back; in such a case the land would revert to the feudal lord.

Medieval and Tudor period

The judgement of 1387 confirmed the supremacy of the Royal Prerogative within the constitution.[52] By the mid 15th century Magna Carta ceased to occupy a central role in English political life.[43] In part this was also due to the rise of an early version of Parliament and to further statutes, some based on the principle of Magna Carta. The Charter, however remained a text for scholars of law. The Charter in the statute books was correctly thought to have arisen from the reign of Henry III and was seen as no more special than any other statute and could be amended and removed. It was not seen (as it was later) as an entrenched set of liberties guaranteed for the people against the Government. Rather, it was an ordinary statute, which gave a certain level of liberties, most of which could not be relied on, least of all against the king. Therefore the Charter had little effect on the governance of the early Tudor period.

The Tudor period would see a growing interest in history. Tudor historians would rediscover the Barnwell chronicler who was more favourable to King John than other contemporary texts. John Bale and Shakespeare would both write plays on King John. Tudor historians were not inclined to regard rebellion as anything but a crime. Those who supported Henry VIII's break with Rome “viewed King John in a positive light as a hero struggling against the papacy, they showed little sympathy for the Great Charter or the rebel barons”.[53]

The first printed edition of Magna Carta was probably the Magna Carta cum aliis Antiquis Statutis of 1508 by Richard Pynson.[54] George Ferrers would publish the first unabridged English language edition of Magna Carta in 1534, and effectively established the numbering of the Charter into 37 chapters; an abridged English language edition had previously been published by John Rastell in 1527.[55] By the end of the 16th century editions of the 1215 Charter would also be printed.

The Charter had no real effect until the Elizabethan era (1558–1603). Magna Carta again began to occupy legal minds, and it again began to shape how that government was run, but in a manner entirely different to that of earlier ages. William Lambarde published “what he thought were law codes of the Anglo-Saxon kings and William the conqueror”.[56] Lambarde would begin the process of misinterpreting English history, soon taken up by others, incorrectly dating documents and giving parliament a false antiquity. Francis Bacon would claim that Clause 39 of the 1215 Charter was the basis of the jury system and due process in a trial. Robert Beale, James Morice, Richard Cosin and the Puritans[57] began to misperceive Magna Carta as a 'statement of liberty', a 'fundamental law' above all law and government. In 1581 Arthur Hall, MP would be one of the first to suffer under this emerging new ideology, when he correctly questioned the antiquity of the House of Commons[58][59] and was without precedent expelled from Parliament.

Edward Coke's opinions

Among the first of respected jurists to seriously write about the great charter was Edward Coke, who influenced how Magna Carta was perceived throughout the Tudor and Stuart periods, though his views were challenged during his lifetime by Lord Ellesmere, and later in the same century by Robert Brady. Coke used the 1225 issue of the Charter.

Coke "reinterpreted or misinterpreted" Magna Carta "misconstruing its clauses anachronistically and uncritically".[60] He would interpret liberties to be much the same as individual liberty.[61] The historian J.C. Holt excused Coke on the grounds that the Charter and its history had itself become 'distorted'.[62]

Coke was instrumental in framing the Petition of Right, which became a substantial supplement to Magna Carta's liberties. During the debates on the matter, Coke famously sought to deny the King's sovereign rights with the claim that "Magna Carta is such a fellow, that he will have no 'sovereign'"; he believed the statutes (not the King) were absolute.[63]

17th and 18th centuries

Whilst Sir Edward Coke took the lead in reinterpreting Magna Carta, he was soon joined by others with a similar ideological stance, resulting in the concept of an ancient constitution—which entailed belief in fundamental laws that supposedly existed since time immemorial, and a belief in the antiquity of Parliament.[64] These beliefs were used to challenge the constitution as it existed under the Stuart Kings.

John Selden would link habeas corpus to Magna Carta[65] during Darnell's Case. Sir Henry Spelman, who can be largely credited with first formulating a concept of feudalism (which would ironically be later used to attack the idea of an ancient constitution, notably by Robert Brady), sought to place the origins of Common Law in Anglo-Saxon laws.[66] Antiquarians would seek out documents to support the views of their compatriots, such as Sir Robert Cotton, whose collection of manuscripts would later form the basis for the British Library, and who discovered two original copies of King John's Charter.

The Petition of Right of 1628 sought to add to Magna Carta in the manner of the Articuli super Cartas or the Six Statutes. Charles I however, did not grant it as law and he was under no legal restriction.[67] The problem as before in history was that the King was not bound by the law as adherents of Magna Carta believed. As before in history armed force would be used, first in 1642–49 and again in 1689.

With the advent of the republic it was questionable whether Magna Carta still applied. John Milton called for “great actions, above the form of law and custom”. Whilst Oliver Cromwell had much disdain for Magna Carta, at one point describing it as "Magna Farta" to a defendant who sought to rely on it[68] he agreed to rule with the advice and consent of his council.[69]

Different radical groups held differing opinions of Magna Carta. The Levellers rejected history and law as presented by their contemporaries, holding instead to an 'anti-Normanism' viewpoint.[70] John Lilburne regarded Magna Carta as being less than the freedoms that supposedly existed under the Anglo-Saxons before being crushed by the Norman yoke. Richard Overton would describe Magna Carta as a “a beggarly thing containing many marks of intolerable bondage”.[71] Both however saw Magna Carta as a valuable declaration of liberties that could be used against governments they disagreed with. Lilburne said "the ground of my freedom, I build upon the Grand Charter of England", while Overton said that when arrested, he hung on to his copy of Coke on Magna Carta, shouting "murder, murder, murder" as they wrested "the Great Charter of England's Liberties and Freedoms from me".[72] Gerrard Winstanley leader of the more extreme Diggers stated “The best lawes that England hath, [viz., the Magna Carta] were got by our Forefathers importunate petitioning unto the kings that still were their Task-masters; and yet these best laws are yoaks and manicles, tying one sort of people to be slaves to another; Clergy and Gentry have got their freedom, but the common people still are, and have been left servants to work for them.”

The first attempt at a proper Historiography was undertaken by Robert Brady[73] who refuted the supposed antiquity of parliament and the belief in the immutable continuity of the law, and realised the liberties of the Charter were limited and were effective only because it was the grant of the King; by putting Magna Carta in historical context he questioned its contemporary political relevance.[74] However, Brady's history would not survive the Glorious Revolution, which “...marked a setback for the course of English historiography.”[75]

The Glorious Revolution reinforced the century's ideological interpretations of history, which would later become known as the Whig interpretation of history. Reinforced with Lockean concepts the Whigs believed England's constitution to be a Social contract, based on documents such as Magna Carta, the Petition of Right and The Bill of Rights.[76] Ideas about the nature of law in general were beginning to change. In 1716 the Septennial Act was passed, which had a number of consequences. Firstly, it showed that Parliament no longer considered its previous statutes unassailable, as this act provided that the parliamentary term was seven years, whereas fewer than twenty-five years had passed since the Triennial Act (1694), which provided that a parliamentary term was three years. It also greatly extended the powers of Parliament. Under this new constitution Monarchal absolutism was replaced by Parliamentary supremacy. It was quickly realised that Magna Carta stood in the same relation to the King-in-Parliament as it had to the King without Parliament. This supremacy would be challenged by the likes of Granville Sharp. Sharp regarded Magna Carta to be a fundamental part of the constitution, and that it would be treason to repeal any part of it. Sharp also held that the Charter prohibited slavery.[77]

Sir William Blackstone published a critical edition of the 1215 Charter in 1759, and gave it the numbering system still used today.[46]

In 1763 an MP, John Wilkes was arrested for writing an inflammatory pamphlet, No. 45, 23 April 1763; he cited Magna Carta incessantly. Lord Camden denounced the treatment of Wilkes as a contravention of Magna Carta.

Prophet of a new revolutionary age, Thomas Paine in his Rights of Man would disregard Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights on the grounds they were not a written constitution devised by elected representatives.

United States

When Englishmen left their homeland for the new world, they brought with them charters establishing the colonies. The Massachusetts Bay Company charter for example stated the colonists would "have and enjoy all liberties and immunities of free and natural subjects." The Virginia Charter of 1606 (which was largely drafted by Sir Edward Coke) stated the colonists would have all "liberties, franchises and immunities" as if they had been born in England. The Massachusetts Body of Liberties contained similarities to clause 29 of Magna Carta, and the Massachusetts General Court in drawing it up viewed Magna Carta as the chief embodiment of English common law.[78] The other colonies would follow their example. In 1638 Maryland sought to recognise Magna Carta as part of the law of the province but it was not granted by the King.[79]

In 1687 William Penn published The Excellent Privilege of Liberty and Property: being the birth-right of the Free-Born Subjects of England, which contained the first copy of Magna Carta printed on American soil. Penn's comments reflected Coke's, indicating a belief that Magna Carta was a fundamental law.[80] The colonists drew on English lawbooks leading them to an anachronistic interpretation of Magna Carta, believing it guaranteed trial by jury and habeas corpus.[81]

The development of Parliamentary sovereignty in the British Isles did not constitutionally affect the Thirteen Colonies, which retained an adherence to English common law, but it would come to directly affect the relationship between Britain and the colonies.[82] When American colonists raised arms against Britain, they were fighting not so much for new freedom, but to preserve liberties and rights, as believed to be enshrined in Magna Carta and as later included in the Bill of Rights. American Revolutionaries would supplement this with ideas of natural right.

In 1787 when the revolutionaries gathered to draft a constitution they built upon the legal system they knew and admired, English common law, and on Lockean philosophy.

The American Constitution is the supreme law of the land, recalling the manner in which Magna Carta had come to be regarded as fundamental law. This heritage is quite apparent. In comparing Magna Carta with the Bill of Rights: the Fifth Amendment guarantees: "No person shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law." In addition, the United States Constitution included a similar writ in the Suspension Clause, article 1, section 9: "The privilege of the writ habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety may require it." Each of these proclaim no person may be imprisoned or detained without proof that he or she did wrong. The Ninth Amendment to the United States Constitution states that, "The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people." The framers of the United States Constitution wished to ensure that rights they already held, such as those provided by Magna Carta, were not lost unless explicitly curtailed in the new United States Constitution.[83][84]

The United States Supreme Court has explicitly referenced Lord Coke's analysis of Magna Carta as an antecedent of the Sixth Amendment's right to a speedy trial.[85]

Nineteenth century and beyond

Whilst radicals such as Sir Francis Burdett believed that Magna Carta could not be repealed, the 19th century would see the beginning of the repeal of many of the clauses of Magna Carta. The clauses were either obsolete and/or had been replaced by later legislation.

William Stubbs's Constitutional History of England would be the high-water mark of the Whig interpretation of history. Stubbs believed that Magna Carta had been a major step in the shaping of the English people and he believed that the Barons at Runnymede were not just the Barons but the people.[86]

This view of history however, was passing. At the popular level William Howitt in Cassell's Illustrated history of England would note that it was fiction that King John's Charter was the same Magna Carta as was on the statute books and stated that "The Barons, in fact, were amongst the greatest traitors that England ever produced”.[87] Frederic William Maitland provided a more academic history in History of English Law before the Time of Edward I, which began to move Magna Carta from the myth that had grown up around it back to its historical roots. In many literary representations of the medieval past, however, Magna Carta remained the foundation for many diverse constructions of English national identity. Some authors instrumentalized the medieval roots of the document to preserve the social status quo while others utilized the precious national inheritance to change perceived economic injustice.[88]

In 1904 Edward Jenks published in the Independent Review an article entitled The Myth of Magna Carta, which undermined the traditionally accepted view of Magna Carta.[89] Historians like A. F. Pollard would agree with Jenks in considering Coke to have 'invented' Magna Carta, noting that the Charter at Runnymede had not meant popular liberty at all.[90]

Sellar and Yeatman in their parody 1066 and All That would play on the supposed importance of Magna Carta and its supposed universal liberty: "Magna Charter was therefore the chief cause of Democracy in England, and thus a Good Thing for everyone (except the Common People)".

Influences on later constitutions

Many attempts to draft constitutional forms of government, including the United States Constitution, trace their lineage back to Magna Carta.

The British dominions, Australia and New Zealand,[91] Canada[92] (except Quebec), and formerly Union of South Africa and Southern Rhodesia, reflected influence of Magna Carta in their law, and the Charter impacted generally on the states that evolved from the British Empire.[93]

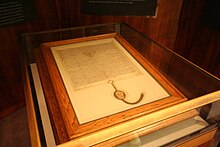

Exemplifications

Numerous copies, known as exemplifications, were made each time it was issued, so all of the participants would each have one – in the case of the 1215 copy, one for the royal archives, one for the Barons of the Cinque Ports, and one for each of the 40 counties of the time. If there ever was one single 'master copy' of Magna Carta sealed by King John in 1215, it has not survived. Four exemplifications of the original 1215 text remain, all of which are located in England, some on permanent display:

- The 'burnt copy', was found in the archives of Dover Castle in 1630 by Sir Edward Dering and sent to the antiquarian Sir Robert Cotton and is assumed to be the copy sent to the Cinque Ports on or after 24 June 1215. It was subsequently damaged in a fire at Ashburnham House where the Cotton Library was housed, and is now virtually illegible. It is the only one of the four to have its seal surviving, which remains however as a lump of shapeless wax. It is currently held by the British Library (Cotton Charter XIII.31a).[94]

- Another 1215 exemplification is held by the British Library (Cotton MS. Augustus II.106).

- One owned by Lincoln Cathedral, normally on display at Lincoln Castle. It has an unbroken attested history at Lincoln since 1216. We hear of it in 1800 when the Chapter Clerk of the Cathedral reported that he held it in the Common Chamber, and then nothing until 1846 when the Chapter Clerk of that time moved it from within the Cathedral to a property just outside. In 1848, Magna Carta was shown to a visiting group who reported it as "hanging on the wall in an oak frame in beautiful preservation". It went to the New York World Fair in 1939. In 1941, after war broke out with Japan, Magna Carta was sent to Fort Knox, along with the U.S. Declaration of Independence and Constitution, until 1944, when it was deemed safe to return them.[95] Having returned to Lincoln, it has been back to the United States on various occasions since then.[96] It was taken out of display for a time to undergo conservation in preparation for its visit to the United States, where it was exhibited at the Contemporary Art Center of Virginia from 30 March to 18 June 2007 in recognition of the Jamestown quadricentennial.[97][98] From 4 to 25 July 2007, the document was displayed at the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia,[99] returning to Lincoln Castle afterwards. The document returned to New York to be displayed at the Fraunces Tavern Museum from 15 September to 15 December 2009 and has since returned to Lincoln.[100][101]

- One owned by and displayed at Salisbury Cathedral. It is the best preserved of the four.[102]

Other early versions of Magna Carta survive. Durham Cathedral possesses 1216, 1217, and 1225 copies.[103]

A near-perfect 1217 copy is held by Hereford Cathedral and is occasionally displayed alongside the Mappa Mundi in the cathedral's chained library. Remarkably, the Hereford Magna Carta is the only one known to survive along with an early version of a Magna Carta 'users manual', a small document that was sent along with Magna Carta telling the Sheriff of the county to observe the conditions outlined in the document.[104]

Four copies are held by the Bodleian Library in Oxford. Three of these are 1217 issues and one a 1225 issue. On 10 December 2007, these were put on public display for the first time.[105] One of the Bodleian exemplifications from 1217 (once possibly held by Gloucester Cathedral) was displayed at San Francisco's California Palace of the Legion of Honor 7 May – 6 June 2011.

In 1952 the Australian Government purchased a 1297 copy of Magna Carta for £12,500 from King's School, Bruton, England.[106] This copy is now on display in the Members' Hall of Parliament House, Canberra. In January 2006, it was announced by the Department of Parliamentary Services that the document had been revalued down from A$40m to A$15m.

Only one copy (a 1297 copy in cursiva anglicana handwriting with the royal seal of Edward I) is in private hands. It was held by the Brudenell family, earls of Cardigan, who owned it for five centuries before they sold it to the Perot Foundation in 1984. This copy, having been on long-term loan to the US National Archives, was auctioned at Sotheby's New York on 18 December 2007. The Perot Foundation sold it to "...have funds available for medical research, for improving public education and for assisting wounded soldiers and their families."[107] It fetched US$21.3 million,[108] It was bought by David Rubenstein of The Carlyle Group,[109] who after the auction said, "I thought it was very important that the Magna Carta stay in the United States and I was concerned that the only copy in the United States might escape as a result of this auction." Rubenstein's copy is on permanent loan to the National Archives in Washington, D.C.[110]

The Rubenstein Magna Carta was removed from display 2 March 2011 for conservation treatment and reencasement in an anoxic environment provided by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) the government agency responsible for the 1950s encasement of the Charters of Freedom. After treatment and encasement by National Archives conservators, Magna Carta was put back on display for the public on 17 February 2012.[111]

Usage of the definite article, spelling "Magna Carta"

Since there is no direct, consistent correlate of the English definite article in Latin, the usual academic convention is to refer to the document in English without the article as "Magna Carta" rather than "the Magna Carta". According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first written appearance of the term was in 1218: "Concesserimus libertates quasdam scriptas in magna carta nostra de libertatibus" (Latin: "We concede the certain liberties here written in our great charter concerning liberties"). However, "the Magna Carta" is frequently used in both academic and non-academic speech.

Especially in the past, the document has also been referred to as "Magna Charta", but the pronunciation was the same. "Magna Charta" is still an acceptable variant spelling recorded in many dictionaries due to continued use in some reputable sources. From the 13th to the 17th centuries, only the spelling "Magna Carta" was used. The spelling "Magna Charta" began to be used in the 18th century but never became more common despite also being used by some reputable writers.[112][113]

Popular perceptions

Symbol and practice

Magna Carta is often a symbol for the first time the citizens of England were granted rights against an absolute king. However, in practice the Commons could not enforce Magna Carta in the few situations where it applied to them, so its reach was limited. Also, a large part of Magna Carta was copied, nearly word for word, from the Charter of Liberties of Henry I, issued when Henry I rose to the throne in 1100, which bound the king to laws that effectively granted certain civil liberties to the church and the English nobility.

Many documents form Magna Carta

Although Magna Carta is popularly thought of as the document forced upon King John in 1215, this version of the charter was almost immediately annulled. Later monarchs reissued the document, but without the most direct challenges to their power, and without the provisions intended to right immediate wrongs rather than make long-term constitutional changes. The version that forms part of English law is actually that of 1297. Magna Carta can therefore refer to any one of several related (but not identical) 13th century documents, or indeed to the various charters as a whole.

The document was unsigned

Popular perception is that King John and the barons signed Magna Carta. There were no signatures on the original document, however, only a single seal placed by the king. The words of the charter—Data per manum nostram—signify that the document was personally given by the king's hand. By placing his seal on the document, the King and the barons followed common law that a seal was sufficient to authenticate a deed, though it had to be done in front of witnesses. John's seal was the only one, and he did not sign it. The barons neither signed nor attached their seals to it.[114]

Perception in America

The document is also honoured in America, where it is an antecedent of the United States Constitution and Bill of Rights. In 1957, the American Bar Association erected the Runnymede Memorial.[115] In 1976, the UK lent one of four surviving originals of the 1215 Magna Carta to the U.S. for its bicentennial celebrations, and also donated an ornate case to display it. The original was returned after one year, but a replica and its case are still on display in the U.S. Capitol Crypt in Washington, D.C.[116] One of four surviving originals of the 1297 Magna Carta is also on display in the U.S. National Archives.

21st-century Britain

In 2006, BBC History held a poll to recommend a date for a proposed "Britain Day". 15 June, which was the date of the original 1215 Magna Carta, received most votes, above other suggestions such as D-Day, VE Day, and Remembrance Day. The outcome was not binding, although the then Chancellor Gordon Brown had previously given his support to the idea of a new national day to celebrate British identity.[117] It was used as the name for an anti-surveillance movement in the 2008 BBC series The Last Enemy. According to a poll carried out by YouGov in 2008, 45% of the British public do not know what Magna Carta is.[118] However, its perceived guarantee of trial by jury and other civil liberties led to Tony Benn referring to the debate over whether to increase the maximum time terrorist suspects could be held without charge from 28 to 42 days as "the day Magna Carta was repealed".[119]

Pop music

Rapper Jay-Z named his twelfth studio album Magna Carta Holy Grail.

See also

- Ankerwycke Yew

- The Baronial Order of Magna Charta

- Cestui que

- Charter of the Forest

- Charter of Liberties

- Concordat of Worms

- Divine Right of Kings

- Fundamental Laws of England

- Henry de Bracton

- History of democracy

- History of human rights

- Human rights

- Magna Carta Place

- New Brabantian Constitution

- Quia Emptores

- Statutes of Mortmain

- subpoena ad testificandum

- Petition of Right

- Tax choice

References

- ^ http://www.salisburycathedral.org.uk/history.magnacarta.php

- ^ "Magna Carta 1215, French translation (MC 1215 Fr)". Holt, J.C.‚ 'A Verncaular-French Text of Magna Carta 1215', English Historical Review, 89 (1974), 346–64.

- ^ Danny Danziger & John Gillingham, "1215: The Year of Magna Carta"(2004 paperback edition) p278

- ^ "Magna Carta: a precedent for recent constitutional change". Judiciary of England and Wales Speeches. 15 June 2005. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ^ Holt, J.C. Magna Carta (1965) p.21

- ^ a b Clanchy, M.T. Early Medieval England Folio Society (1997) p.139

- ^ "United States Constitution Q + A". The Charters of Freedom. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ Thomas, Ralph V. Magna Carta Pearson 2003 pp39–40 & pp53–54

- ^ Danziger & Gillingham (2004) pp.256–258

- ^ Danziger & Gillingham (2004) pp.258–259

- ^ Poole, A.L. From Domesday Book to Magna Carta, 1087–1216 Oxford University Press 2nd edition (1963) p471-472

- ^ Holt, J.C. The Northerners: A Study in the Reign of King John Oxford University Press New edition (1992) p115

- ^ Holt, J.C. The Northerners: A Study in the Reign of King John Oxford University Press New edition (1992) p112

- ^ Within this article dates before 14 September 1752 are in the Julian calendar, later dates are in the Gregorian calendar.

- ^ Holt, J.C. The Northerners: A Study in the Reign of King John Oxford University Press New edition (1992) p107

- ^ "Roger of Wendover". Britannia.com. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ Leeming, John Robert (1915). Stephen Langton: Hero of Magna Charta (1215 A.D.), septingentenary (700th anniversary), 1915 A.D. London: Skeffington & Son. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ Poole, A.L. From Domesday Book to Magna Carta, 1087–1216 Oxford University Press 2nd edition (1963) p479

- ^ Carpenter, David A. The Minority of Henry III University of California Press (1992) p12

- ^ Danziger & Gillingham (2004) p. 264

- ^ Crouch, David William Marshal Longman (1996) p114

- ^ Holt, J.C. Magna Carta Cambridge University Press 2nd Edition (1992) p1

- ^ Clanchy, M.T. A History Of England: Early Medieval England Folio Edition (1997) p141

- ^ Magna Charta translation, Barons at Runnymede, Magna Charta Period Feudal Estates, h2g2, King John and the Magna Carta

- ^ Hewitt, H.J. Mediaeval Cheshire Manchester University Press (1929) p.9

- ^ Holt, J.C. Magna Carta Cambridge University Press 2nd Edition (1992) pp.379-380

- ^ Clanchy, M.T. A History Of England: Early Medieval England Folio Edition (1997) p145

- ^ Powicke, Sir Maurice The Thirteenth Century 1216–1307 Oxford University Press 2nd edition (1962) p5

- ^ White, A.B. The Name Magna Carta in The English Historical Review (1915) pp472-475 and Note on the Name Magna Carta in The English Historical Review (1917) pp554–555

- ^ Clanchy, M.T. A History Of England: Early Medieval England Folio Edition (1997) pp141–142

- ^ Clanchy, M.T. A History Of England: Early Medieval England Folio Edition (1997) p147

- ^ Holt, J.C. Magna Carta Cambridge University Press 2nd Edition (1992) p394

- ^ Prestwich, Michael Edward I Yale (1997) p427

- ^ Halsbury Statutes Volume 10 4th edition (2007) p6

- ^ "Magna Carta (1297)". The National Archive. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ^ "UK Statute Law". Statutelaw.gov.uk. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "Confirmatio Cartarum". Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- ^ Prestwich, Michael Edward I Yale (1997) p427

- ^ Prestwich, Michael Edward I Yale (1997) p434

- ^ Menache, Sophia Clement V Cambridge University Press (2002)p253

- ^ Robison, William B. and Fritze, Ronald H. (eds) Historical dictionary of late medieval England, 1272–1485 Greenwood Press (2002) entry on Articuli super Cartas pp34–35

- ^ Prestwich, MichaelEdward I University of California Press (1988) pp547-548

- ^ a b Turner, Ralph V. Magna Carta Pearson (2003) p123

- ^ Thompson, Faith Magna Carta – Its Role in the Making of the English Constitution 1300–1629(1948)pp9-10

- ^ a b c "(Magna Carta) (1297) (c. 9)". UK Statute Law Database. Retrieved 2 September2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Turner, Ralph V. Magna Carta Pearson (2003) pp67-68

- ^ Madison, P.A. (2 August 2010). "Historical Analysis of the Meaning of the 14th Amendment's First Section". The Federalist Blog. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ Ambrose Evans-Pritchard (6 December 2009). "It's a return to the Star Chamber as Europe finally tramples Magna Carta into the dust". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ^ Gordon v. Justice Court, 12 Cal. 3d 323 (1974).

- ^ Danziger, Gillingham 2004 p.262

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Turner, Ralph V. Magna Carta Pearson (2003) p127

- ^ Turner, Ralph V. Magna Carta Pearson (2003) p138

- ^ Thompson, Faith Magna Carta – Its Role in the Making of the English Constitution 1300–1629 University of Minnesota Press (1948) p.146

- ^ Thompson, Faith Magna Carta – Its Role in the Making of the English Constitution 1300–1629 University of Minnesota Press (1948) pp.147–149

- ^ Turner, Ralph V. Magna Carta Pearson (2003) p.140

- ^ Thompson, Faith Magna Carta – Its Role in the Making of the English Constitution 1300–1629 University of Minnesota Press (1948) pp.216–230

- ^ Pocock, J.G.A. The Ancient Constitution and the Feudal Law Cambridge University Press reisssue (1987) p.154

- ^ Wright, Herbert G. The Life and Works of Arthur Hall of Grantham, Member of Parliament, Courtier and First Translator of Homer Into English (1919) p.72

- ^ Turner, Ralph V. Magna Carta Longman (2003) 148

- ^ Holt, J.C. Magna Carta Cambridge University Press 2nd edition (1992) p12

- ^ Holt, J.C. Magna Carta Cambridge University Press 2nd edition (1992) pp20–21

- ^ Turner, Ralph V. Magna Carta Longman (2003) 157

- ^ Pocock, J.G.A. The Ancient Constitution and the Feudal Law Cambridge University Press (1987)

- ^ Turner, Ralph V. Magna Carta Pearson (2003) p156

- ^ Greenberg, Janelle The Radical Face of the Ancient Constitution: St Edward's 'Laws' in Early Modern Political Thought Cambridge University Press (2001) p148

- ^ Russell, Conrad Unrevolutionary England, 1603–1642 Hambledon Press (1990) p41

- ^ Magna Carta: a Precedent For Recent Constitutional Change, a speech by Harry Woolf, Baron Woolf, Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, given on 15 June 2005 at Royal Holloway, University of London

- ^ Woolrych, Austyn in David L. Smith (Editor) Cromwell and the Interregnum: The Essential Readings Wiley-Blackwell (2003) p66

- ^ Pocock, J.G.A. The Ancient Constitution and the Feudal Law Cambridge University Press (1987) p127

- ^ Kewes, Paulina The uses of history in early modern England University of California Press (2006) 226

- ^ Danziger & Gillingham (2004) pp.281–282

- ^ Pocock, J.G.A. The Ancient Constitution and the Feudal Law Cambridge University Press (1987) "The Brady Controversy" chapter pp182-228

- ^ Turner, Ralph V. Magna Carta Pearson (2003) p165

- ^ Pocock, J.G.A. The Ancient Constitution and the Feudal Law Cambridge University Press (1987) p228

- ^ Turner, Ralph V. Magna Carta Pearson (2003) p170

- ^ Linebaugh, Peter The Magna Carta Manifesto: Liberties and Commons for All University of California Press (2008) p113-114 and p96

- ^ Hazeltine, H.D. The influence of Magna Carta on American Constitutional Development in Malden, Henry Elliot (editor) Magna Carta commemoration essays (1917) p 194

- ^ Hazeltine, H.D. The influence of Magna Carta on American Constitutional Development in Malden, Henry Elliot (editor) Magna Carta commemoration essays (1917) p 195

- ^ Turner, Ralph V. Magna Carta Pearson (2003) p210

- ^ Turner, Ralph V. Magna Carta Pearson (2003) p 211

- ^ Hazeltine, H.D. The influence of Magna Carta on American Constitutional Development in Malden, Henry Elliot (editor) Magna Carta commemoration essays (1917) pp 183–184

- ^ Frederic Jesup Stimson, The Law of the Federal and State Constitutions of the United States; Book One, Origin and Growth of the American Constitutions, 2004, Introductory, Lawbook Exchange Ltd, ISBN 1-58477-369-3

- ^ Charles Lund Black, A New Birth of Freedom, 1999, p. 10, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-07734-3

- ^ "',Klopfer v. North Carolina',, 386 U.S. 213 (1967)". Caselaw.lp.findlaw.com. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Turner, Ralph V. Magna Carta Pearson (2003) pp199–200

- ^ Volume 6 1862 pV

- ^ Clare A. Simmons, "Absent Presence: The Romantic-Era Magna Charta and the English Constitution," in Medievalism in the Modern World. Essays in Honour of Leslie J. Workman, ed. Richard Utz and Tom Shippey (Turnhout: Brepols, 1998), pp. 69–83.

- ^ Galef, David Second thoughts: a focus on rereading Wayne State University Press (1998) p78–79

- ^ Pollard, Albert F. The History of England; a study in political evolution (1912)pp31-32

- ^ Clark, David The Icon of Liberty: The Status and Role of Magna Carta in Australian and New Zealand Law Melbourne University Law Review 34 (2000)

- ^ Kennedy, William Paul Mcclure The Constitution of Canada; An Introduction to Its Development and Law (1922) p228

- ^ Drew, Katherine Fischer Magna Carta Greenwood (2004) pxvi & pxxiii

- ^ Davis, G.R.C., Magna Carta, published by the British Library Board, 1977, p.36

- ^ Fort Knox Bullion Depository, GlobalSecurity.org

- ^ Knight, Alec (17 April 2004). "Magna Charta: Our Heritage and Yours". National Society Magna Charta Dames and Barons. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 2 September 2007.

- ^ "Magna Carta & Four Foundations of Freedom". Contemporary Art Center of Virginia. 2007. Retrieved 2 September 2007.

- ^ "By Our Heirs Forever". Contemporary Art Center of Virginia. 2007. Retrieved 2 September 2007.

- ^ "Magna Carta on Display Beginning 4 July " (Press release). National Constitution Center. 30 May 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 2 September 2007.

- ^ Copy of Magna Carta Travels to New York in Style, The New York Times, 13 September 2009

- ^ Magna Carta and the Foundations of Freedom, Fraunces Tavern Museum

- ^ Award for cathedral Magna Carta, BBC News Online, 4 August 2009

- ^ "Magna Carta: Where can I see a copy?". Icons: A Portrait of England. Culture Online. Retrieved 2 September 2007.

- ^ "Magna Carta at Hereford Cathedral".

- ^ "Magna Carta on display at the Bodleian". 10 December 2007. Retrieved 12 December 2007.

- ^ Harry Evans, Bad King John and the Australian Constitution

- ^ Barron, James (25 September 2007). "Magna Carta is going on the auction block". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- ^ "Magna Carta copy fetches $24m". Sydney Morning Herald. 19 December 2007. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- ^ "Magna Carta Sells for $21.3m in New York" (– Scholar search). The Washington Post. 19 December 2007. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|format= - ^ A.E. Dick Howard "Magna Carta Comes to America", American Heritage, Spring/Summer 2008.

- ^ National Archives and Records Administration (12 February 2012). "New National Archives Video Short Documents 1297 Magna Carta Encasement Project: Magna Carta to Return to Public Display on February 17" (Press release). Archives.gov.

- ^ Dictionary of Modern Legal Usage, Bryan A. Garner

- ^ Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of English Usage

- ^ Browning, Charles Henry (1898). "The Magna Charta Described". The Magna Charta Barons and Their American Descendants ... Philadelphia. p. 50. OCLC 9378577.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "National Archives Featured Documents: Magna Carta". Archives.gov. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ [1], Architect of the Capitol. Retrieved 22 July 2012

- ^ "Magna Carta tops British day poll". BBC News. 30 May 2006. Retrieved 2 September 2007.

- ^ "Magna Carta what? English charter 'a mystery to 45% of population'". The Daily Telegraph. UK. 13 March 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ^ "So will the revolution start in Haltemprice and Howden?". The Independent. UK. 14 June 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- Magna Carta in Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Article from Australia's Parliament House about the relevance of Magna Carta

- J. C. Holt (1992). Magna Carta. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-27778-7.

- I. Jennings: Magna Carta and its influence in the world today

- H. Butterfield; Magna Carta in the Historiography of the 16th and 17th centuries

- G.R.C. Davis; Magna Carta

- J. C. Dickinson; The Great Charter

- G. B. Adams; Constitutional History of England

- W. S. McKechnie; Magna Carta: A Commentary (2d ed. 1914, repr. 1960)

- A. Pallister; Magna Carta the Legacy of Liberty

- A. Lyon; Constitutional History of the United Kingdom

- G. Williams and J. Ramsden; Ruling Britannia, A Political History of Britain 1688–1988

- Royal letter promulgating the text of Magna Carta (1215), treasure 3 of the British Library displayed via The European Library

External links

- Text of the Magna Carta 1297 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk.

- "Treasures in Full: Magna Carta", two copies from 1215 from the British Library in multi-media format.

- Annotated English translation of 1215 version

- The Magna Carta in Medieval History of Navarre

- "Magna Carta" Latin Text

- "Magna Carta Libertatum" Latin and English text

- Baronial Order of Magna Charta

- The Magna Carta Manifesto: Liberties and Commons for All by Peter Linebaugh U of C Press 2008

- "Magna Carta and Its American Legacy" The influence of Magna Carta on the United States Constitution and Bill of Rights

- Parliament House, Canberra, Australia and Bad King John and the Australian Constitution Lecture commemorating the 700th anniversary of the 1297 issue of Magna Carta.

- The Magna Carta English translations. Project Gutenberg celebratory etext 10000

- Text of Magna Carta English translation, with introductory historical note. From the Internet Medieval Sourcebook.

- Notes prepared by Nancy Troutman

- Magna Carta glossary

- Magna Carta copy to be auctioned from BBC News

- Scholarly essay on Magna Carta at Sotheby's website

- Magna Carta – a Guide from Unlock Democracy.

- New York Daily News article on Magna Carta coming to Manhattan, 4 July 2008

- Interactive, high-resolution view of a copy from 1297, previously owned by Ross Perot and given to the US National Archives

- The coats of arms of the barons together with the will of King John [dead link]

- Use dmy dates from December 2012

- Magna Carta

- 1210s in England

- 1215 in Europe

- 1215 in law

- Barons' Wars

- Cotton Library

- Constitutional laws of England

- History of human rights

- Manuscripts

- Medieval charters and cartularies

- Memory of the World Register

- Norman and Medieval England

- Political charters

- Medieval English law