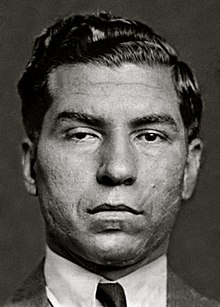

Lucky Luciano

Charles "Lucky" Luciano | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Salvatore Lucania November 11, 1897 |

| Died | January 26, 1962 (aged 64) |

| Occupation(s) | Crime boss, gangster, bootlegger. |

| Signature | |

Charles "Lucky" Luciano (pronounced /luːtʃˈɑːn[invalid input: 'ɵ']/;[1] born Salvatore Lucania[2] November 24, 1897 – January 26, 1962), was a Sicilian-born American mobster. Luciano is considered the father of modern organized crime in the United States for splitting New York City into five different Mafia crime families and the establishment of the first Commission. He was the first official boss of the modern Genovese crime family. He was, along with his associate Meyer Lansky, instrumental in the development of the National Crime Syndicate in the United States.

Early life

Salvatore Lucania was born on November 24, 1897 in Lercara Friddi, Sicily.[3][4] Luciano's parents, Antonio and Rosalia Lucania, had four other children: Bartolomeo (born 1890), Giuseppe (born 1898), Filippia (born 1901), and Concetta. Luciano's father worked in a sulfur mine in Sicily.[5] In 1907, when Luciano was 10 years old, the family immigrated to the United States.[6][7] They settled in New York City in the borough of Manhattan on its Lower East Side, a popular destination for Italian immigrants.[8] At age 14, Luciano dropped out of school and started a job delivering hats, earning $7 per week. However, after winning $244 in a dice game, Luciano quit his job and went to earning money on the street.[5] That same year, Luciano's parents sent him to the Brooklyn Truant School.[9]

As a teenager, Luciano started his own gang. Unlike other street gangs whose business was petty crime, Luciano offered protection to Jewish youngsters from Italian and Irish gangs for 10 cents per week. Around this time, he met Meyer Lansky, his future business partner and close friend.

It is not clear how Luciano earned the nickname "Lucky". It may have come from surviving a severe beating by three men in the 1920s, as well as a throat slashing. This was because Luciano refused to work for another mob boss.[6] From 1916 to 1936, Luciano was arrested 25 times on charges including assault, illegal gambling, blackmail and robbery, but spent no time in prison.[10] The name "Lucky" may have also been a mispronunciation of Luciano's surname "Lucania".

Prohibition

On January 17, 1920, the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified, and Prohibition lasted until the amendment was repealed in 1933. The Amendment prohibited the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcoholic beverages. As there was still a substantial demand for alcohol, this provided criminals with an added source of income.

By 1921, Luciano had met many future Mafia leaders, including Vito Genovese and Frank Costello, his longtime friend and future business partner through the Five Points Gang. The same year, Lower Manhattan gang boss Joe Masseria recruited Luciano as one of his gunmen.[11]

At some point in the early 1920s, Luciano left Masseria and started working for gambler Arnold "the Brain" Rothstein. Rothstein immediately saw the potential windfall from Prohibition and educated Luciano on running bootleg alcohol as a business.[12] Luciano, Costello, and Genovese started their own bootlegging operation with financing from Rothstein.[12]

Rothstein served as a mentor for Luciano; among other things, Rothstein taught him how to move in high society. In 1923, after a botched drug deal damaged Luciano's criminal reputation, he bought 200 expensive seats to the Jack Dempsey–Luis Firpo boxing match in the Bronx and distributed them to top gangsters and politicians. Rothstein then took Luciano on a shopping trip to Wanamaker's Department Store in Manhattan to buy high-end clothes for the fight. The strategy worked, and Luciano's reputation was saved.[13]

By 1925, Luciano was grossing over $12 million a year. He had a net income of around $4 million each year after the costs of bribing politicians and police. Luciano and his partners ran the largest bootlegging operation in New York, one that also extended into Philadelphia. He imported Scotch whisky from Scotland, rum from the Caribbean, and whisky from Canada. Luciano was also involved in illegal gambling.

On November 2, 1928, a bookkeeper shot and killed Rothstein over a gambling debt.[14] With Rothstein's death, Luciano quickly pledged fealty again to Masseria.

Rise to power

Luciano soon became a top aide in the Masseria organization. In contrast to Rothstein, Masseria was an uneducated man with poor manners and limited managerial skills. By the late 1920s, Masseria's main rival was boss Salvatore Maranzano, who had come from Sicily to run the Castellammarese clan activities. Maranzano didn't want to pay commission to Masseria, and the ensuing rivalry eventually escalated into the infamous Castellammarese War, which raged from 1928 to 1931 and resulted in the deaths of both Maranzano and Masseria.

Masseria and Maranzano were so-called "Mustache Petes": older, traditional Mafia bosses who had started their criminal careers in Italy. They believed in upholding the supposed Old World Mafia principles of "honor", "tradition", "respect", and "dignity". These bosses refused to work with non-Italians, and were even skeptical of working with non-Sicilians. Some of the most traditional bosses only worked with men with roots in their own Sicilian village. Luciano, in contrast, was willing to work with Italian, Jewish, and Irish gangsters. For this reason, he was shocked to hear traditional Sicilian mafiosi lecture him about his dealings with close friend Frank Costello, whom they called "the dirty Calabrian".[15]

Luciano soon began cultivating ties with other younger mobsters who had been born in Italy, but began their criminal careers in the United States. Known as the Young Turks, they chafed at their bosses' conservatism. Luciano wanted to use lessons he learned from Rothstein to turn their gang activities into criminal empires.[16] As the war progressed, this group came to include future mob leaders such as Costello, Vito Genovese, Albert Anastasia, Joe Adonis, Joe Bonanno, Carlo Gambino, Joe Profaci, Tommy Gagliano, and Tommy Lucchese. The Young Turks believed that their bosses' greed and conservatism were keeping them poor while the Irish and Jewish gangs got rich. Luciano's vision was to form a national crime syndicate in which the Italian, Jewish, and Irish gangs could pool their resources and turn organized crime into a lucrative business for all.[17]

In October 1929, Luciano was forced into a limousine at gun point by three men, beaten and stabbed, and dumped on a beach on Staten Island. He somehow survived the ordeal but was forever marked with a scar and droopy eye. The identity of his abductors was never established. When picked up by the police after the beating, Luciano said that he had no idea who did it. However, in 1953, Luciano told an interviewer that it was the police who kidnapped and beat him.[18] Another story was that Maranzano ordered the attack.[19] The most important consequence of this episode was the press coverage it engendered, introducing Luciano to the New York public.

Power play

In early 1931, Luciano decided to eliminate Masseria. The war had been going poorly for Masseria, and Luciano saw an opportunity to switch allegiance. In a secret deal with Maranzano, Luciano agreed to engineer Masseria's death in return for receiving Masseria's rackets and becoming Maranzano's second-in-command.[20]

On April 15, 1931, Luciano invited Masseria and two other associates to lunch in a Coney Island restaurant. After finishing their meal, the mobsters decided to play cards. At that point, Luciano went to the bathroom. Four gunmen – Genovese, Anastasia, Adonis and Benjamin "Bugsy" Siegel – then walked into the dining room and shot and killed Masseria and his two men.[15] With Maranzano's blessing, Luciano took over Masseria's gang and became Maranzano's lieutenant.[20] The Castellammarese War was over.

With Masseria gone, Maranzano divided all the Italian-American gangs in New York City into Five Families. As per his original deal with Maranzano, Luciano took over the old Masseria gang. The other four families were headed by Maranzano, Profaci, Gagliano, and Vincent Mangano. Maranzano promised that all the families would be equal and free to make money. However, at a meeting of crime bosses in Upstate New York, Maranzano declared himself capo di tutti capi, the absolute boss of organized crime in America. Maranzano also whittled down the rival families' rackets in favor of his own. Luciano appeared to accept these changes, but was merely biding his time before removing Maranzano.[15] Although Maranzano was slightly more forward-thinking than Masseria, Luciano had come to believe that Maranzano was even more greedy and hidebound than Masseria had been.[20]

By September 1931, Maranzano realized that Luciano was a threat, and hired Vincent "Mad Dog" Coll, an Irish gangster, to kill him. However, Lucchese alerted Luciano that he was marked for death. On September 10, Maranzano ordered Luciano and Genovese to come to his office at 230 Park Avenue in Manhattan. Convinced that Maranzano planned to murder them, Luciano decided to act first. He sent to Maranzano's office four Jewish gangsters whose faces were unknown to Maranzano's people. They had been secured with the aid of Lansky and Siegel, who were both Jewish.[21] Disguised as government agents, two of the gangsters disarmed Maranzano's bodyguards. The other two, aided by Tommy Lucchese, who was there to point Maranzano out, stabbed Maranzano multiple times before shooting him.[17][22]

This assassination was the first of what would later be fabled as the "Night of the Sicilian Vespers." Then on September 13 the corpses of two other Maranzano allies, Samuel Monaco and Louis Russo were retrieved from Newark Bay, showing evidence of torture. Meanwhile Joseph Siragusa, leader of the Pittsburgh crime family, was shot to death in his home. The October 15 disappearance of Joe Ardizonne, head of the Los Angeles crime family, would later be regarded as part of this alleged plan to quickly eliminate the old-world Sicilian bosses.[21] The idea of an organized mass purge, directed by Luciano and engineered by Louis Lepke, is a myth, however.[23]

Reorganizing Cosa Nostra

With the death of Maranzano, Luciano became the dominant organized crime boss in the United States. He had reached the pinnacle of America's underworld, directing criminal rules, policies, and activities along with the other family bosses. Luciano also had his own crime family, which controlled lucrative criminal rackets in New York City such as illegal gambling, bookmaking, loan-sharking, drug trafficking, and extortion. Luciano became very influential in labor and union activities and controlled the Manhattan Waterfront, garbage hauling, construction, Garment Center businesses, and trucking.

Luciano abolished the title of Capo Di Tutti Capi or Boss of All Bosses, insisting that the position created trouble between the families, rather than declare himself the most powerful and make himself a target for other families. Luciano preferred to quietly maintain control through unofficial alliances with other family bosses. Luciano felt that the ceremony of becoming a "made-man", or an amico nostro, in a crime family was a Sicilian anachronism that should be discontinued. However, Lansky persuaded Luciano to keep the practice, arguing that young people needed rituals to promote obedience to the family. Luciano also stressed the importance of omertà, the oath of silence. Finally, Luciano kept the five crime families that Maranzano had instituted.[20]

Luciano elevated his most trusted Italian associates to high-level positions in what was now the Luciano crime family. Genovese became underboss and Costello consigliere. Michael "Trigger Mike" Coppola, Anthony Strollo, Joe Adonis, and Anthony Carfano all served as caporegimes. Because Lansky and Siegel were non-Italians, neither man could hold official positions within any Cosa Nostra family. However, Lansky was a top advisor to Luciano and Siegel a trusted associate.

The Commission

Luciano, on the urging of former Chicago boss Johnny Torrio, set up the Commission to serve as the governing body for organized crime. Designed to settle all disputes and decide which families controlled which territories, the Commission has been called Luciano's greatest innovation.[20] Luciano's goals with the Commission were to quietly maintain his own power over all the families, and to prevent future gang wars.

The Commission was originally composed of representatives of the Five Families of New York City, the Philadelphia crime family, the Buffalo crime family, the Los Angeles crime family, and the Chicago Outfit of Al Capone; later, the Detroit crime family and Kansas City crime family were added. The Commission also provided representation for the Irish and Jewish criminal organizations in New York. All Commission members were supposed to retain the same power and had one vote, but in reality some families and bosses were more powerful than others.

In 1935, in its first big test, the Commission ordered gang boss Dutch Schultz to drop his plans to murder Special Prosecutor Thomas Dewey. Luciano argued that a Dewey assassination would precipitate a massive law enforcement crackdown. When Schultz announced that he was going to kill Dewey, or his Assistant David Asch, anyway in the next three days, the Commission quickly arranged Schultz's murder.[24] On October 24, 1935, Schultz was murdered in a tavern in Newark, New Jersey.[25]

Prosecution for pandering

During the early 1930s, Luciano's crime family started taking over small scale prostitution operations in New York City. In June 1935, New York Governor Herbert H. Lehman appointed U.S. Attorney Thomas E. Dewey as a special prosecutor to combat organized crime in New York City.[26] Dewey soon realized that he could attack Luciano, the most powerful gangster in New York, through this prostitution network with the assistance of his aide David Asch.

On February 2, 1936, Dewey launched a massive police raid against 200 brothels in Brooklyn and Manhattan, earning him nationwide recognition as a major "gangbuster". Ten men and 100 women were arrested. However, unlike previous vice raids, Dewey did not release the arrestees. Instead, he took them to court where a judge set bails of $10,000, far beyond their means to pay.[27] By mid-March, several defendants had implicated Luciano.[28] Three of these prostitutes implicated Luciano as the ringleader, who made collections, although David Betillo was in charge of the prostitution ring in New York, and any money that Luciano received was from Betillo. In late March 1936, Luciano received a tip that he was going to be arrested and fled to Hot Springs, Arkansas. Unfortunately for Luciano, a New York detective in Hot Springs on a different assignment spotted Luciano and notified Dewey.[29]

On April 1, 1936, Luciano was arrested in Hot Springs on a criminal warrant from New York. The next day in New York, Dewey indicted Luciano and his accomplices on 60 counts of compulsory prostitution. Luciano's lawyers in Arkansas then began a fierce legal battle against extradition. On April 6, someone offered a $50,000 bribe to Arkansas Attorney General Carl E. Bailey to facilitate Luciano's case. However, Bailey refused the bribe and immediately reported it. On April 17, after all of Luciano's legal motions had been exhausted, Arkansas authorities handed Luciano to three New York City Police Department detectives for transport by train back to New York for trial.[30] When the detectives and their prisoner reached St. Louis, Missouri and changed trains, they were guarded by 20 local policemen to prevent a mob rescue attempt. The men arrived in New York City on April 18, and Luciano was held without bail.[31]

On May 13, 1936, Luciano's pandering trial began.[32] He was accused of being part of a massive prostitution ring known as "the Combination". During the trial, Dewey exposed Luciano for lying on the witness stand through direct quizzing and records of telephone calls; Luciano also had no explanation for why his federal income tax records claimed he made only $22,000 a year, while he was obviously a wealthy man.[20] Dewey ruthlessly pressed Luciano on his long arrest record and his relationships with well-known gangsters such as Ciro Terranova, Louis Buchalter, and Joseph Masseria.[33]

On June 7, 1936, Luciano was convicted on 62 counts of compulsory prostitution.[34] On July 18, 1936, Luciano was sentenced to 30 to 50 years in state prison, along with Betillo and others.[35][36]

Many observers have questioned whether there was enough evidence to support the charges against Luciano. Like nearly all crime families, the Luciano family almost certainly profited from prostitution and extorted money from madams and brothel keepers. However, like most bosses, Luciano created layers of insulation between himself and criminal acts. It would have been significantly out of character for him to be directly involved in any criminal enterprise, let alone a prostitution ring. At least two of his contemporaries have denied that Luciano was ever part of "the Combination". In her memoirs, New York society madam Polly Adler wrote that if Luciano had been involved with "the Combination", she would have known about it. Bonanno, the last surviving contemporary of Luciano's who wasn't in prison, also denied that Luciano was directly involved in prostitution in his book, A Man of Honor.[20]

Prison

Luciano continued to run the Luciano crime family from prison, relaying his orders through acting boss, Vito Genovese. However, in 1937 Genovese fled to Naples, Italy to avoid an impending murder indictment in New York. Luciano appointed his consigliere, Costello, as the new acting boss and the overseer of Luciano's interests.

Luciano was first imprisoned at Sing Sing Correctional Facility in Ossining, New York, but was moved later in 1936 to Clinton Correctional Facility in Dannemora, New York, far away from New York City. At Clinton, co-defendant Dave Betillo prepared special dishes for Luciano in a kitchen set aside by authorities.[20] Luciano was assigned a job in the prison laundry.[37] Luciano used his influence to help get the materials to build a church at the prison, which became famous for being one of the only freestanding churches in the New York State correctional system and also for the fact that on the church's altar are two of the original doors from the Victoria, the ship of Ferdinand Magellan.

Legal appeals of Luciano's conviction continued until October 10, 1938, when the U.S. Supreme Court refused to review his case.[38] At this point, Luciano stepped down as boss, and Costello formally took over the family.

World War II, freedom and deportation

During World War II, the U.S. government struck a secret deal with the imprisoned Luciano. In 1942, the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence was concerned about German and Italian agents entering the United States through the New York waterfront. They also worried about sabotage in these facilities. Knowing that the Cosa Nostra controlled the waterfront, the Navy contacted Lansky about a deal with Luciano. To facilitate negotiations, the State of New York transferred Luciano from Clinton prison to Great Meadow Correctional Facility in Comstock, New York, which was much closer to New York City.[39]

The Navy, the State of New York and Luciano eventually concluded a deal. In exchange for a commutation of his sentence, Luciano promised the complete assistance of his organization in providing intelligence to the Navy. Luciano ally Albert Anastasia, who controlled the docks, allegedly promised no dockworker strikes during war. In preparation for the 1943 allied invasion of Sicily, Luciano allegedly provided the U.S. military with Mafia contacts in Sicily.[37]

The value of Luciano's contribution to the war effort is highly debated. In 1947, the naval officer in charge of Operation Underworld discounted the value of Luciano's wartime aid.[40] A 1954 report ordered by Governor Dewey stated that Luciano provided many valuable services to Naval Intelligence.[41] The enemy threat to the docks, Luciano allegedly said, was manufactured by the sinking of the SS Normandie in New York harbor, supposedly directed by Anastasia's brother, Anthony Anastasio.[42][43] However, the official investigation of the ship sinking found no evidence of sabotage.[44]

On January 3, 1946, as a presumed reward for his alleged wartime cooperation, now Governor Thomas E. Dewey reluctantly commuted Luciano's pandering sentence on condition that he did not resist deportation to Italy.[45] Luciano accepted the deal, although he still maintained that he was a U.S. citizen and not subject to deportation. On February 2, 1946, two federal immigration agents transported Luciano from Sing Sing prison to Ellis Island in New York Harbor for deportation proceedings.[46] On February 9, the night before his departure, Luciano shared a spaghetti dinner on his freighter with Anastasia and five other guests.[47]

On February 10, 1946, Luciano's ship sailed from Brooklyn harbor for Italy.[47] This was the last time he would see the United States. On February 28, after a 17-day voyage, Luciano's ship arrived in Naples. On arrival, Luciano told reporters he would probably reside in Sicily.[48]

Luciano was deeply hurt about having to leave the United States, a country he had considered his home ever since his arrival at age 10. During his exile, Luciano frequently encountered US military men and American tourists during train trips in Italy. Luciano enjoyed these meetings and gladly posed for photographs and signed autographs.

The Havana Conference

In October 1946, Luciano secretly moved to Havana, Cuba. Luciano first took a freighter from Naples to Caracas, Venezuela, then flew to Rio De Janeiro. He then flew to Mexico City and doubled back to Caracas, where he took a private plane to Camaguey, Cuba, finally arriving on October 29. Luciano was then driven to Havana, where he moved into an estate in the Miramar section of the city.[49]

Luciano's objective in going to Cuba was to be closer to the United States so that he could resume control over American Cosa Nostra operations and eventually return to the United States.[50] Lansky was already established as a major investor in Cuban gambling and hotel projects.

In 1946, Lansky called a meeting of the heads of the major crime families in Havana that December. The ostensible reason was to see singer Frank Sinatra perform. However, the real reason was to discuss mob business with Luciano in attendance. The three topics to discuss: the heroin trade, Cuban gambling, and what to do about Siegel and the floundering Flamingo Hotel project in Las Vegas. The Conference took place at the Hotel Nacional de Cuba and lasted a little more than a week.

On December 20, during the conference, Luciano had a private meeting with Genovese in Luciano's hotel suite. In 1945, Genovese had been returned from Italy to New York to face trial on his 1934 murder charge.[51] However, in June 1946, the charges were dismissed and Genovese was free to return to mob business.[52] Unlike Costello, Luciano had never trusted Genovese. In the meeting, Genovese tried to convince Luciano to become a titular boss of bosses and let Genovese run everything. Luciano calmly rejected Genovese's suggestion:

"There is no Boss of Bosses. I turned it down in front of everybody. If I ever change my mind, I will take the title. But it won't be up to you. Right now you work for me and I ain't in the mood to retire. Don't you ever let me hear this again, or I'll lose my temper."[53]

Soon after the Havana Conference began, the U.S. government learned about Luciano in Cuba. Luciano had been publicly fraternizing with Sinatra as well as visiting numerous nightclubs, so his presence was no secret in Havana.[54] The U.S. started putting pressure on the Cuban government to expel him. On February 21, 1947, U.S. Narcotics Commissioner Harry J. Anslinger notified the Cuban government that the United States would block all shipment of narcotic prescription drugs to Cuba while Luciano was there.[16][55] Two days later, the Cuban government announced that Luciano was in custody and would be deported to Italy within 48 hours.[56] Luciano was placed on a Turkish freighter that was sailing to Genoa, Italy.

Operating in Italy

After Luciano's secret trip to Cuba, he spent the rest of his life in Italy under tight police surveillance.

When Luciano arrived in Genoa from Cuba on April 11, 1947, he was arrested and sent to a jail in Palermo. On May 11, a regional commission in Palermo warned Luciano to stay out of trouble and released him from jail.[57]

In early July 1949, police in Rome arrested Luciano on suspicion of involvement in the shipping of narcotics to New York. On July 15, after a week in jail, police released Luciano without filing any charges. He was also permanently banned from visiting Rome.[58]

On June 9, 1951, Luciano was questioned by police in Naples on suspicion of illegally bringing $57,000 in cash and a new American car into Italy. After 20 hours of questioning, police released Luciano without any charges.[59]

In 1952, the Italian government revoked Luciano's Italian passport after complaints from U.S. and Canadian law enforcement officials.[60]

On November 19, 1954, an Italian judicial commission in Naples applied strict limits on Luciano for two years. He was required to report to the police every Sunday, to stay home every night, and to not leave Naples without police permission. The commission cited Luciano's alleged involvement in the narcotics trade as the reason for these restrictions.[61]

Despite the law enforcement surveillance, Luciano was able to greatly expand narcotics trafficking to the United States by Cosa Nostra, making it one of organized crime's most lucrative ventures. Between October 10 and October 14, 1957, Luciano oversaw a parley of more than 30 Sicilian and American Mafia leaders to draw up plans for the smuggling and distribution of heroin into the United States. According to Selwyn Raab, an investigative reporter for The New York Times, it was at the Luciano meeting, held in the Grand Hotel et des Palmes in Palermo, Sicily, that a plan was put into place through which Sicilians were responsible for distributing heroin in the U.S., while the American mobsters collected a share of the income as "franchise fees". Luciano's plan included a scheme to expand the tiny heroin and cocaine market in the U.S. by reducing the price and focusing on working class white and black urban neighborhoods.[citation needed]

Personal life

In 1929, Luciano met Gay Orlova, a featured dancer in one of Broadway's leading nightclubs, Hollywood.[62] They were inseparable, but never married up until he went to prison.[62]

In early 1948, Luciano met Igea Lissoni, an Italian nightclub dancer 20 years his junior, whom he later described as the love of his life. In the summer, Lissoni moved in with him. Although some reports said the couple married in 1949, others state that they only exchanged rings.[5][63] Luciano and Lissoni lived together in Luciano's house in Naples. Although Luciano adored Lissoni, he continued to have affairs with other women. This led to numerous arguments with Lissoni, with Luciano striking her on several occasions.[64] In 1959, Lissoni died of breast cancer.

Luciano never had children. He once provided his reasons for that:

I didn't want no son of mine to go through life as the son of Luciano, the gangster. That's one thing I still hate Dewey for, making me a gangster in the eyes of the world.[65]

American power struggle

By 1957, Genovese felt strong enough to move against Luciano and his acting boss in New York, Frank Costello. He was aided in this move by Anastasia crime family underboss Carlo Gambino. On May 2, 1957, Costello was shot and slightly wounded by a gunman outside of his apartment building. Soon after this attack, Costello conceded control of what is called today the Genovese crime family to Genovese. Luciano was powerless to stop it.[66] On October 26, 1957, Genovese and Gambino arranged the murder of Albert Anastasia, another Luciano ally.[67] Gambino took over what is now called the Gambino crime family. Genovese now believed himself to be the top boss in the Cosa Nostra.

In November 1957, Genovese called a meeting of Cosa Nostra bosses in Apalachin, New York to approve his takeover of the Luciano family and to establish his national power. Instead, the Apalachin Meeting turned into a fiasco when law enforcement raided the meeting. Over 65 high-ranking mobsters were arrested and the Cosa Nostra was subjected to publicity and numerous grand jury summons.[68] The enraged mobsters blamed Genovese for this disaster, opening a window of opportunity for Genovese's opponents.

Costello, Luciano, and Gambino met in a hotel in Palermo, Sicily, to discuss their plan of action. In his own power move, Gambino had deserted Genovese. After their meeting, Luciano allegedly paid an American drug seller $100,000 to falsely implicate Genovese in a drug deal.[69]

On April 4, 1959, Genovese was convicted in New York of conspiracy to violate federal narcotics laws.[70] Sent to prison for 15 years, Genovese tried to run his crime family from prison until his death in 1969.[71] Meanwhile, Gambino now became the most powerful man in the Cosa Nostra.

Death and legacy

On January 26, 1962, Luciano died of a heart attack at Naples International Airport. Luciano had gone to the airport to meet with American producer Martin Gosch about a film based on his life. To avoid antagonizing other Cosa Nostra members, Luciano had previously refused to authorize a film, but reportedly relented after Lissoni's death. After the meeting with Gosch, Luciano was stricken with a heart attack and died. Luciano was unaware that Italian drug agents had followed him to the airport in anticipation of arresting him on drug smuggling charges.[5]

Three days later, 300 people attended a funeral service for Luciano in Naples. Luciano's body was conveyed along the streets of Naples in a horse-drawn black hearse.[72] With the permission of the U.S. government, Luciano's relatives took his body back to New York for burial. He was buried in St. John's Cemetery in Middle Village, Queens. More than 2,000 mourners attended his funeral. Luciano's longtime friend, Gambino crime family boss Carlo Gambino, gave his eulogy.

Gambino was the only other boss besides Luciano to have complete control of the Commission and virtually every Mafia family in the United States. In popular culture, proponents of the Mafia and its history often debate as to who was the greater between Luciano and his contemporary, Al Capone. The much-publicized exploits of Capone with the Chicago Outfit made him the most famous mobster in American history, but he did not exert influence over other Mafia families as Luciano did in creating and running The Commission.

In 1998, Time magazine characterized Luciano as the "criminal mastermind" among the top 20 most influential builders and titans of the 20th century.[73]

In popular culture

Films

- The Valachi Papers (1972) – Luciano was portrayed by Angelo Infanti[74]

- Lucky Luciano (1973) – Luciano was portrayed by Gian Maria Volonté[75]

- The Cotton Club (1984) – Luciano was portrayed by Joe Dallesandro[76]

- Mobsters (1991) – Luciano was portrayed by Christian Slater[77]

- Bugsy (1991) – Luciano was portrayed by Bill Graham[78]

- Billy Bathgate (1991) – Luciano was portrayed by Stanley Tucci[79]

- White Hot: The Mysterious Murder of Thelma Todd (TV 1991) – Luciano was portrayed by Robert Davi[80]

- The Outfit (1993) – Luciano was portrayed by Billy Drago[81]

- Hoodlum (1997) – Luciano was portrayed by Andy García[82]

- Bonanno: A Godfather's Story (TV 1999) – Luciano was portrayed by Vince Corazza[83]

- Lansky (TV 1999) – Luciano was portrayed by Anthony LaPaglia[84]

- The Real Untouchables (TV 2001) – Luciano was portrayed by David Viggiano[85]

TV series

- The Witness (1960–1961) – Luciano was portrayed by Telly Savalas[86]

- The Gangster Chronicles (1981) – Luciano was portrayed by Michael Nouri[87]

- Boardwalk Empire (2010–2014) – Luciano was portrayed by Vincent Piazza[88]

Documentary series

- Mafia's Greatest Hits – Luciano features in the second episode of UK history TV channel Yesterday's documentary series.

Books

- Luciano's Luck, Jack Higgins (1981). Fictional based on the Luciano's WWII supposed war efforts.

- The Last Testament of Lucky Luciano, Martin A. Gosch and Richard Hammer (1975). Semi-Autobiographical, based on Luciano's entire lifespan as dictated by him. [89]

See also

References

- ^ "Say How: I, J, K, L". NLS Other Writings. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. February 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/350578/Lucky-Luciano

- ^ Birth Record

- ^ Critchley, David The origin of organized crime in America: the New York City mafia, 1891–1931 pp. 212–213

- ^ a b c d "Luciano Dies at 65. Was Facing Arrest in Naples". New York Times. January 27, 1962. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

Lucky Luciano died of an apparent heart attack at Capodichino airport today as United States and Italian authorities prepared to arrest him in a crackdown on an international narcotics ring.

- ^ a b Biography.com (A&E Television Networks). "Lucky Luciano Biography". Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ^ "Who2 Biography: Charles "Lucky" Luciano, Gangster". Answers.com. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ^ "Immigration: The Journey to America: The Italians". Projects by Students for Students. Oracle ThinkQuest Education Foundation. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ^ Stolberg, p. 117

- ^ "Lucania is Called Shallow Parasite". New York Times. June 19, 1936. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

- ^ Newark, p. 22

- ^ a b Stolberg, p. 119

- ^ Pietrusza, David. Rothstein The Life, Times, and Murder of the Criminal Genius Who Fixed the 1919 World Series (2nd ed.). New York: Basic Books. p. 202. ISBN 0465029396.

- ^ Stolberg, p. 11

- ^ a b c Sifakis

- ^ a b Maas, Peter. The Valachi Papers.

- ^ a b "Genovese family saga". Crime Library.

- ^ Feder & Joesten, pp. 67–69

- ^ Eisenberg, D.; Dan, U.; Landau, E. (1979). Meyer Lansky: Mogul of the Mob. New York: Paddington Press. ISBN 044822206X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h The Five Families. MacMillan. p. [page needed]. Retrieved June 22, 2008.

- ^ a b "Lucky Luciano: Criminal Mastermind," Time, Dec. 7, 1998

- ^ "The Genovese Family," Crime Library, Crime Library,

- ^ The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Mafia, p. 283

- ^ Newark, p. 81

- ^ "Schultz's Murder Laid to Lepke Aide". New York Times. March 28, 1941. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- ^ "Dewey Chosen by Lehman to Head Racket Inquiry; Acceptance Held Certain". New York Times. June 30, 1935. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- ^ "Vice Raids Smash '$12,000,000 Ring'". New York Times. February 3, 1936. Retrieved June 22, 2012.

- ^ Stolberg, p. 127

- ^ Stolberg, p. 128

- ^ "Luciano is Given Up and Is On Way Back". New York Times. April 17, 1946. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

- ^ "Luciano Due Today, Heavily Guarded". New York Times. April 18, 1936. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

- ^ Stolberg, p. 133

- ^ Stolberg, p. 148

- ^ "Lucania Convicted with 8 in Vice Ring on 62 Counts Each". New York Times. June 8, 1936. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- ^ "Luciano Trial Website".

- ^ "Lucania Sentenced to 30 to 50 Years; Court Warns Ring". New York Times. June 19, 1936. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- ^ a b Newark, p. 137

- ^ "Supreme Court Bars a Review to Luciano". New York Times. October 11, 1938. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- ^ Kelly, Robert J. (1999). The Upperworld and the Underworld: Case Studies of Racketeering and Business Infiltrations in the United States. Criminal Justice and Public Safety. New York: Kluwer Academic / Plenum Publishers. p. 107. ISBN 0306459698.

- ^ "Luciano War Aid Called Ordinary". New York Times. February 27, 1947. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

- ^ Kihss, Peter (October 9, 1977). "Secret Report Cites". New York Times. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

- ^ Bondanella, Peter E. Hollywood Italians: Dagos, Palookas, Romeos, Wise Guys, and Sopranos. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004, p. 200. ISBN 0-8264-1544-X

- ^ Gosch & Hammer, pp. 260, 268, cited in Martin, David (November 10, 2010). "Luciano: SS Normandie Sunk as Cover for Dewey". Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ^ Trussell, C.P. (April 16, 1942). "Carelessness Seen in Normandie Fire". New York Times. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ^ "Dewey Commutes Luciano Sentence". New York Times. January 4, 1946. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ "Luciano Leaves Prison". New York Times. February 3, 1946. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ a b "Pardoned Luciano on His Way to Italy". New York Times. February 11, 1946. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ "Luciano Reaches Naples". New York Times. March 1, 1946. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ English, p. 3

- ^ Sifakis, p. 215

- ^ "Genovese Denies Guilt". New York Times. June 3, 1945. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- ^ "Genovese is Freed of Murder Charge". New York Times. June 11, 1946. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- ^ English, p. 28

- ^ English, p. 49

- ^ "U.S. Ends Narcotics Sales to Cuba While Luciano is There". New York Times. February 22, 1947. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ "Luciano to Leave Cuba in 48 Hours". New York Times. February 23, 1947. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ "Luciano Released from Palermo Jail". New York Times. May 15, 1947. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ "Luciano Freed; Barred from Rome". New York Times. July 16, 1949. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- ^ "Luciano Questioned on Smuggling Count". New York Times. June 10, 1951. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- ^ "Luciano Loses Passport". New York Times. July 17, 1952. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- ^ "Luciano, 'Danger to Society', Is Ordered To Stay Home Nights in Naples for 2 Years". New York Times. November 20, 1954. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

Charles (Lucky) Luciano, former New York vice king, will have to stay home every night for the next two years.

- ^ a b Gosch & Hammer

- ^ "City Boy". Time. July 25, 1949.

- ^ Newark, p. 241

- ^ Newark, p. 240

- ^ "Costello is Shot Entering Home: Gunman Escapes". New York Times. May 3, 1957. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- ^ "Anastasia Slain in a Hotel Here: Led Murder, Inc". New York Times. October 26, 1957. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

Death took The Executioner yesterday. Umberto (called Albert) Anastasia, master killer for Murder, Inc., a homicidal gangster troop that plagued the city from 1931 to 1940, was murdered by two gunmen.

- ^ "65 Hoodlums Seized in a Raid and Run Out of Upstate Village". New York Times. November 15, 1957. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- ^ Sifakis, p. 23

- ^ "Genovese Guilty in Narcotics Plot". New York Times. April 4, 1959. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ Grutzner, Charles (December 25, 1968). "Jersey Mafia Guided From Prison by Genovese". New York Times. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ "300 Attend Rites for Lucky Luciano". New York Times. January 30, 1962. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- ^ Buchanan, Edna. "Criminal Mastermind: Lucky Luciano". Time.

- ^ IMDb: The Valachi Papers (1972)

- ^ IMDb: Lucky Luciano (1973)

- ^ IMDb: The Cotton Club (1984)

- ^ IMDb: Mobsters (1991)

- ^ IMDb: Bugsy (1991)

- ^ IMDb: Billy Bathgate (1991)

- ^ IMDb: White Hot: The Mysterious Murder of Thelma Todd (TV 1991)

- ^ IMDb: The Outfit (1993)

- ^ IMDb: Hoodlum (1997)

- ^ IMDb: Bonanno: A Godfather's Story (TV 1999)

- ^ IMDb: Lansky (TV 1999)

- ^ IMDb: The Real Untouchables (TV 2001)

- ^ IMDb: The Witness (TV Series 1960–1961)

- ^ IMDb: The Gangster Chronicles (TV Series 1981)

- ^ IMDb: Boardwalk Empire (TV Series 2010)

- ^ http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/991912.The_Last_Testament_of_Lucky_Luciano

Further reading

- Gosch, Martin A.; Hammer, Richard (1974). The Last Testament of Lucky Luciano. Boston: Little Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-32140-0.

- Raab, Selwyn (2006). Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-36181-5.

- Klerks, Cat (2005). Lucky Luciano: The Father of Organized Crime. Altitude Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 1-55265-102-9.

- Powell, Hickman (2000). Lucky Luciano, his amazing trial and wild witnesses. Barricade Books, Incorporated. ISBN 0-8065-0493-5.

- Feder, Sid; Joesten, Joachim (1994). Luciano Story. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80592-8. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- Newark, Tim (2010). Lucky Luciano: the real and the fake gangster (1st ed.). New York: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-0-312-60182-9. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- Stolberg, Mary M. (1995). Fighting organized crime: politics, justice, and the legacy of Thomas E. Dewey. Boston: Northeastern University Press. ISBN 1-55553-245-4. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- Sifakis, Carl (2005). The Mafia Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Facts On File. ISBN 0-8160-6989-1. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- English, T. J. (2008). Havana nocturne: how the mob owned Cuba – and then lost it to the revolution. New York: Harper. ISBN 0061712744. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

External links

- Lucky Luciano at Find a Grave

- 'Havana' Revisited: An American Gangster in Cuba NPR, June 5, 2009

- Photograph of Meyer Lansky, Lucky Luciano, and others at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel from the Lloyd Sealy Library Digital Collections

- Ill-formatted IPAc-en transclusions

- 1897 births

- 1962 deaths

- American mob bosses

- Bosses of the Genovese crime family

- Capi di tutti capi

- Burials at St. John's Cemetery (Queens)

- Deaths from myocardial infarction

- Five Points Gang

- Italian mob bosses

- Italian Roman Catholics

- Nicknames of criminals

- People deported from the United States

- People from the Province of Palermo

- Prohibition-era gangsters

- Sing Sing

- Smallpox survivors