Presidency of George Washington

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

American Revolution

1st President of the United States

First term

Second term

Legacy

|

||

The presidency of George Washington, began on April 30, 1789, when Washington was inaugurated as the first President of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1797. Washington took office after the 1788–89 presidential election, the nation's first quadrennial presidential election, in which he was elected unanimously. Washington was re-elected unanimously in the 1792 presidential election, and chose to retire after two terms. He was succeeded by his vice president, John Adams of the Federalist Party.

Washington had established his preeminence among the new nation's Founding Fathers through his service as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War and as president of the 1787 Constitutional Convention. Once the Constitution was approved, it was widely expected that Washington would become the first President of the United States, despite his own desire to retire from private life. In his first inaugural address expressed both his reluctance to accept the presidency and his inexperience with the duties of civil administration, but Washington proved an able leader.

Washington presided over the establishment of the new federal government – appointing all of the high-ranking officials in the executive and judicial branches, shaping numerous political practices, and establishing the site of the permanent capital of the United States. He supported Alexander Hamilton's economic policies whereby the federal government assumed the debts of the state governments and established the First Bank of the United States, the United States Mint, and the United States Customs Service. Congress passed the Tariff of 1789, the Tariff of 1790, and an excise tax on whiskey to fund the government and, in the case of the tariffs, address the trade imbalance with Britain. Washington personally led federal soldiers in suppressing the Whiskey Rebellion, which arose in opposition to the administration's taxation policies. He directed the Northwest Indian War, which saw the United States establish control over Native American tribes in the Northwest Territory. In foreign affairs, he assured domestic tranquility and maintained peace with the European powers despite the raging French Revolutionary Wars by issuing the 1793 Proclamation of Neutrality. He also secured two important bilateral treaties, the 1794 Jay Treaty with Great Britain and the 1795 Treaty of San Lorenzo with Spain, both of which fostered trade and helped secure control of the American frontier. To protect American shipping from Barbary pirates and other threats, he re-established the United States Navy with the Naval Act of 1794.

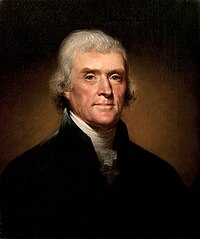

Greatly concerned about the growing partisanship within the government and the detrimental impact political parties could have on the fragile unity holding the nation together, Washington struggled throughout his eight-year presidency to hold rival factions together. He was, and remains, the only U.S. president never to be affiliated with a political party.[1] In spite of his efforts, debates over Hamilton's economic policy, the French Revolution, and the Jay Treaty deepened ideological divisions. Those that supported Hamilton formed the Federalist Party, while his opponents coalesced around Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and formed the Democratic-Republican Party. While criticized for furthering the partisanship he sought to avoid by identifying himself with Hamilton, Washington is nonetheless considered by scholars and political historians as one of the greatest presidents in American history, usually ranking in the top three with Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Delano Roosevelt.[2]

Election of 1788–89

Following the Philadelphia Constitutional Convention of 1787, a fatigued Washington returned to his estate, Mount Vernon. He seemed intent on resuming his retirement and letting others govern the nation with its new frame of government.[3] The American public at large, however, wanted no one but Washington to be the nation's first president.[4][5] The first U.S. presidential campaign was in essence what today would be called a grassroots effort to convince Washington to accept the office.[4] Letters poured into Mount Vernon informing him of public sentiment and imploring him to accept; from former comrades in arms, and from across the Atlantic. Gouverneur Morris urged Washington to accept, writing "[Among the] thirteen horses now about to be coupled together, there are some of every race and character. They will listen to your voice and submit to your control. You therefore must, I say must mount this seat." Alexander Hamilton was one of the most dedicated in his efforts to get Washington to accept the presidency, as he foresaw himself receiving a powerful position in the administration.[6] The comte de Rochambeau urged Washington to accept, as did the Marquis de Lafayette, who exhorted Washington to "not to deny your acceptance of the office of President for the first years." Washington replied "Let those follow the pursuits of ambition and fame, who have a keener relish for them, or who may have more years, in store, for the enjoyment."[5] In an August 1788 letter, Washington further expounded on his feelings regarding the election, stating,

I should unfeignedly rejoice, in case the Electors, by giving their votes to another person would save me from the dreaded dilemma of being forced to accept or refuse... If that may not be–I am, in the next place, earnestly desirous of searching out the truth, and knowing whether there does not exist a probability that the government would be just as happily and effectually carried into execution without my aid."[7]

Less certain was the choice for the vice presidency, which contained little definitive job description in the constitution. The only official role of the vice president was as the president of the Senate, a duty unrelated to the executive branch. The Constitution stipulated that the position would be awarded to the runner-up in the presidential election, or the person with the second highest amount of electoral votes. Because Washington was from Virginia, many, including Washington himself (who remained neutral on the candidates) assumed that a vice president would be chosen from one of the northern states to ease sectional tensions.[8] In an August 1788 letter, Thomas Jefferson wrote that he considered John Adams and John Hancock, both prominent citizens from Massachusetts, to be the top contenders. He suggested John Jay, James Madison, and John Rutledge as other possible candidates.[9] In January of 1789, upon hearing that Adams would probably win the vice presidency, Washington wrote to Henry Knox, saying "[I am] entirely satisfied with the arrangement for filling the second office."[8]

Each state's presidential electors gathered in their state's capital on February 4, 1789 to cast their votes for the president. As the election occurred prior to ratification of the Twelfth Amendment, each elector cast two votes for the presidency, though the electors were not allowed to cast both votes for the same person. Under the terms of the constitution, the individual who won the most electoral votes would become president while the individual with the second-most electoral votes would become vice president. Each state's votes were sealed and delivered to Congress to be counted.[10][a]

By the time the votes were cast, Washington had declared his willingness to serve, and was preparing to leave Mount Vernon for New York City, the nation's capital.[5] On April 6, 1789, the House and Senate, meeting in joint session, counted the electoral votes and certified that Washington had been elected President of the United States with 69 electoral votes. They also certified that Adams, with 34 electoral, had been elected as Vice President.[10][11] The other 35 electoral votes were divided among: John Jay (9), Robert H. Harrison (6), John Rutledge (6), John Hancock (4), George Clinton (3), Samuel Huntington (2), John Milton (2), James Armstrong (1), Benjamin Lincoln (1), and Edward Telfair (1).[13] Informed of his election on April 14,[10] Washington wrote in a letter to Edward Rutledge that in accepting the presidency, he had given up "all expectations of private happiness in this world."[14]

Start of first presidential and vice presidential terms

The first presidential term and the first vice presidential term both officially started on March 4, 1789, the date set by the Congress of the Confederation for the beginning of operations of the federal government under the new U.S. Constitution.[15][16] However, due to the formidable difficulties of long-distance travel in 18th century America, they did not commence until several weeks later.[17] Although the House of Representatives and the Senate convened on the prescribed date, both soon adjourned due to lack of a quorum.[18] As a result, the presidential electoral votes could not be counted or certified. On April 1, the House convened with a quorum present for the first time, and the representatives began their work. The Senate first achieved a quorum on April 6. That is the date upon which the electoral votes were counted.[19][20]

Adams arrived in New York a few days before Washington, and first presided over the Senate on April 21.[21] Washington was inaugurated as the first President of the United States on April 30, 1789, at Federal Hall in New York, then the nation's capitol. The presidential oath of office was administered by Robert Livingston, the Chancellor of the State of New York.[19] Washington took the oath on the building's second floor balcony, in view of throngs of people gathered on the streets.[19] The Bible used in the ceremony was from St. John's Lodge No. 1, A.Y.M.,[22] and was opened at random to Genesis 49:13 ("Zebulun shall dwell at the haven of the sea; and he shall be for an haven of ships; and his border shall be unto Zidon").[23] Afterward, Livingston shouted "Long live George Washington, President of the United States!"[14] Historian John R. Alden indicates that Washington added the words "so help me God" to the oath.[24]

In his inaugural address (Full text ![]() ), delivered in the Senate chamber after taking the oath,[25] Washington again touched upon his reluctance to accept the presidency,

), delivered in the Senate chamber after taking the oath,[25] Washington again touched upon his reluctance to accept the presidency,

Fellow-Citizens of the Senate and of the House of Representatives: Among the vicissitudes incident to life no event could have filled me with greater anxieties than that of which the notification was transmitted by your order, and received on the 14th day of the present month.[23]

He also addressed the subject of amending the Constitution to include a Bill of Rights,[26] urging Congress

...to decide how far an exercise of the occasional power delegated by the fifth article of the Constitution is rendered expedient at the present juncture by the nature of objections which have been urged against the system, or by the degree of inquietude which has given birth to them. Instead of undertaking particular recommendations on this subject, in which I could be guided by no lights derived from official opportunities, I shall again give way to my entire confidence in your discernment and pursuit of the public good; for I assure myself that whilst you carefully avoid every alteration which might endanger the benefits of an united and effective government, or which ought to await the future lessons of experience, a reverence for the characteristic rights of freemen and a regard for the public harmony will sufficiently influence your deliberations on the question how far the former can be impregnably fortified or the latter be safely and advantageously promoted.[23]

Administration

Cabinet

| The Washington cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | George Washington | 1789–1797 |

| Vice President | John Adams | 1789–1797 |

| Secretary of State | John Jay | 1789–1790 |

| Thomas Jefferson | 1790–1793 | |

| Edmund Randolph | 1794–1795 | |

| Timothy Pickering | 1795–1797 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Alexander Hamilton | 1789–1795 |

| Oliver Wolcott Jr. | 1795–1797 | |

| Secretary of War | Henry Knox | 1789–1794 |

| Timothy Pickering | 1794–1796 | |

| James McHenry | 1796–1797 | |

| Attorney General | Edmund Randolph | 1789–1794 |

| William Bradford | 1794–1795 | |

| Charles Lee | 1795–1797 | |

The new Constitution empowered the president to appoint executive department heads with the consent of the Senate. Three departments had existed under the Articles of Confederation: the Department of War, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Finance Office. The Department of War was retained, while the latter two departments became the Department of State and the Department of the Treasury, respectively. The leaders of these three departments constituted the initial positions in Washington's cabinet. In September 1789, Congress established the position of Attorney General to serve as the chief legal adviser to the president. Though the Attorney General did not oversee a department (the United States Department of Justice would be established in 1870), the position nonetheless became a part of the cabinet. Edmund Randolph became the first Attorney General, while Henry Knox retained his position as head of the Department of War and Thomas Jefferson served as the first Secretary of State. For the key post of Secretary of the Treasury, which would oversee economic policy, Washington chose Alexander Hamilton, after his first choice, Robert Morris, declined. Morris had recommended Hamilton instead, writing "But, my dear general, you will be no loser by my declining the secrataryship of the Treasury, for I can recommend a far cleverer fellow than I am for your minister of finance in the person of your aide-de-camp, Colonel Hamilton."[27] Washington's initial cabinet consisted of one individual from New England (Knox), one individual from the mid-Atlantic (Hamilton), and two Southerners (Jefferson and Randolph).[28]

Jefferson left the Cabinet at the end of 1793.[29] He was replaced by Randolph, while William Bradford took over as Attorney General. Knox left the cabinet in 1794, and was replaced by Timothy Pickering. Hamilton left the cabinet in 1795, as did Randolph. With their departure, Oliver Wolcott became Secretary of the Treasury, and Pickering succeeded Randolph as Secretary of State. James McHenry replaced Pickering as Secretary of War, while Charles Lee became Attorney General after the departure of Bradford.[30]

Hamilton and Jefferson had the greatest impact on cabinet deliberations during Washington's first term. Their deep philosophical differences set them against each other from the outset, and they frequently sparred over economic and foreign policy issues.[31] With Jefferson's departure, Hamilton came to dominate the cabinet,[32] and Washington continued to turn to him for advice even after Hamilton resigned from the Cabinet.[33]

Vice presidency

During his two vice-presidential terms, Adams attended few cabinet meetings, and the president sought his counsel only infrequently. Nonetheless, the two men, according to Adams biographer, John E. Ferling, "jointly executed many more of the executive branch's ceremonial undertakings than would be likely for a contemporary president and vice-president."[34] In the Senate, Adams played a more active role, particularly during his first term. On at least one occasion, he persuaded senators to vote against legislation he opposed, and he frequently lectured the body on procedural and policy matters. He supported Washington's policies by casting 29 tie-breaking votes.[34]

His first incursion into the legislative realm occurred shortly after he assumed office, during the Senate debates over titles for the president and executive officers of the new government. Although the House of Representatives agreed in short order that the president should be addressed simply as "George Washington, President of the United States," the Senate debated the issue at some length.[34] Adams favored the adoption of the style of Highness (as well as the title of Protector of Their [the United States'] Liberties) for the president.[35] Others favored the variant of Electoral Highness or the lesser Excellency."[36] Anti-federalists in the Senate objected to the monarchical sound of them all. In the end, Washington yielded to their objections and the House decided that the title of "Mr. President" would be used.[37]

While Adams brought energy and dedication to the presiding officer's chair, he found the task "not quite adapted to my character."[34][38] Ever cautious about going beyond the constitutional limits of the vice-presidency or of encroaching upon presidential prerogative, Adams often ended up lamenting what he viewed as the "complete insignificance" of his situation. To his wife Abigail he wrote, "My country has in its wisdom contrived for me the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man . . . or his imagination contrived or his imagination conceived; and as I can do neither good nor evil, I must be borne away by others and met the common fate."[39]

Judicial appointments

Through the Judiciary Act of 1789, Congress established a six-member Supreme Court. The court was composed of one Chief Justice and five Associate Justices. It was given exclusive original jurisdiction over all civil actions between states, or between a state and the United States, as well as over all suits and proceedings brought against ambassadors and other diplomatic personnel; and original, but not exclusive, jurisdiction over all other cases in which a state was a party and any cases brought by an ambassador. The Court was given appellate jurisdiction over decisions of the federal circuit courts as well as decisions by state courts holding invalid any statute or treaty of the United States; or holding valid any state law or practice that was challenged as being inconsistent with the federal constitution, treaties, or laws; or rejecting any claim made by a party under a provision of the federal constitution, treaties, or laws.[40]

As the first President, Washington was responsible for appointing the entire Supreme Court. Due to this, he filled more vacancies on the Court than any other president in American history. In September 1789, Washington nominated John Jay as the first Chief Justice and nominated John Rutledge, William Cushing, James Wilson, John Blair, and Robert Harrison as Associate Justices. All were quickly confirmed by the Senate, but after Harrison declined the appointment, Washington appointed James Iredell in 1790. As Associate Justices left the court in subsequent years, Washington appointed Thomas Johnson, William Paterson, and Samuel Chase. Jay stepped down as Chief Justice in 1795 and was replaced by Rutledge, who received a recess appointment as Chief Justice. Rutledge served for six months but resigned after his nomination was rejected by the Senate in December 1795. After the rejection of Rutledge's nomination, Washington appointed Oliver Ellsworth as the third Chief Justice of the United States.[41]

The Judiciary Act also created 13 judicial districts[42] within the 11 states that had then ratified the Constitution; with Massachusetts and Virginia each being divided into two districts.[43] Both North Carolina and Rhode Island were added as judicial districts in 1790 after they ratified the Constitution, as were the subsequent states that Congress admitted to the Union. Additionally, the act established circuit courts and district courts within these districts. The circuit courts, which were composed of a district judge and (initially) two Supreme Court justices "riding circuit," had jurisdiction over more serious crimes and civil cases and appellate jurisdiction over the district courts, while the single-judge district courts had jurisdiction primarily over admiralty cases, along with petty crimes and lawsuits involving smaller claims. The circuit courts were grouped into three geographic circuits to which justices were assigned on a rotating basis.[43] Washington appointed 28 judges to the federal district courts during his two terms in office.[44]

First presidential veto

Washington exercised his presidential veto power for the first time on April 5, 1792 to stop an apportionment act from becoming law. The legislation introduced a new plan for distributed seats in the House of Representatives among the various states in a way that the president deemed unconstitutional.[45][46] After attempting but failing to override the veto, Congress swiftly crafted new legislation, the Apportionment Act of 1792, which Washington signed into law on April 14.[47]

Salary

On September 24, 1789,[48] Congress voted to pay the president a salary of $25,000 a year, and the vice president an annual salary of $5,000.[49] Washington's salary was equal to two percent of the total federal budget in 1789.[50]

Domestic affairs

Selection of permanent U.S. capital

The subject of a permanent capital for the United States was discussed numerous times during the years immediately following the Revolutionary War, however, the Continental Congress could never agree on a site due to regional loyalties and tensions.[51] In September 1788, the Congress of the Confederation selected New York City as the nation's temporary capital under the incoming federal government.[16] The framers of the Constitution granted the new U.S. Congress full governing authority over a federal district, intentionally separate from not beholden to any state.[52] The Constitution, however, said nothing about where it would be. Discussions during the 1st Congress about where the federal district would be located revolved around two locations: one site on the Potomac River near Georgetown; and another site on the Susquehanna River near Wrights Ferry (now Columbia, Pennsylvania). The Susquehanna River site was approved by the House in September 1789, while legislation under consideration in the Senate specified a site on the Delaware River near Germantown, Pennsylvania. No agreement was reached, and the subject was deferred until the second session.[53]

Interest in attracting the capital grew as people realized the commercial benefits and prestige that were at stake.[51] New York City and Philadelphia each built houses for the president.[54] State officials in New York offered to cede Kingston, while Maryland officials offered to cede either Annapolis or Baltimore.[55] Also, as had been the case in earlier debates during the 1780s, regional biases, state pride and local loyalties were potent forces and figured into the contest. There was much maneuvering by northern and southern factions in favor of certain sites,[56] and by interstate coalitions that were formed and dissolved almost daily, as Congress debated the matter during the spring of 1790.[51] More than 20 sites were proposed publicly as candidates for the capital city.[57]

Washington, Jefferson, and James Madison, then a representative from Virginia, all supported a permanent capital on the Potomac; Hamilton backed a temporary capital in New York City, and a permanent one in Trenton, New Jersey. At the same time, Hamilton's funding proposal, a plan in which the federal government would assume debts incurred by states in waging the Revolutionary War was failing to garner enough support to pass. Jefferson, understanding that Hamilton needed southern votes to pass his funding plan, and keenly aware that the Potomac capital concept would fail without additional northern support, made use of an opportunity provided by a chance encounter with Hamilton to an informal dinner meeting at which interested parties could discuss a "mutual accommodation."[51] The deal subsequently struck, known as the Compromise of 1790, cleared the way for passage, in July 1790, of the Residence Act. The act transferred the federal capital to Philadelphia for 10 years, while a permanent capital along the Potomac was under construction. Hamilton's assumption became law with the passage of the Funding Act of 1790.[58][59]

The Residence Act authorized the president to select the specific location of the permanent seat of government, along the Potomac. It also authorized the president to appoint three commissioners to survey and acquire property for this seat. Washington personally oversaw this effort through the end of his presidency. In 1791, the commissioners named the permanent seat of government "The City of Washington in the Territory of Columbia" to honor him. In 1800 the Territory of Columbia became the District of Columbia when the federal government moved to the site;[60] John Adams, Washington's successor, would move into the White House in November 1800.[61]

Economic policy

Among the many contentious issues facing the First Congress during its inaugural session was the issue of how to raise revenue for the federal government. There were both domestic and foreign Revolutionary War-related debts, as well as a trade imbalance with Great Britain that was crippling American industries and draining the nation of its currency. The first effort to begin addressing these issues resulted in the Tariff of 1789, authorizing the collection of duties on imported goods.[62] Signed into law by the president on July 4, 1789, the act established the United States Customs Service and its ports of entry. One year later, the Revenue-Marine was established when Washington signed legislation authorizing construction of ten cutters to enforce federal tariff and trade laws and to prevent smuggling. Until Congress established the Navy Department in 1798, it served as the nation's only armed force afloat. Renamed a century later as the Revenue Cutter Service, it and the U.S. Life-Saving Service were merged in 1915 to form the United States Coast Guard.[63][64]

Various other plans were considered to address the debt issues during the first session of Congress, but none were able to generate widespread support. In September 1789, with no resolution in sight and the close of that session drawing near, Congress directed Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton to prepare a report on credit.[65] In his Report on the Public Credit (the first of three fiscal and economic policy reports), Hamilton called for the federal assumption of state debt and the mass issuance of federal bonds. Hamilton believed that these measures would restore the ailing economy, ensure a stable and adequate money stock, and make it easier for the federal government to borrow during emergencies such as wars.[66] He also proposed redeeming the promissory notes issued by the Continental Congress during the American Revolution at full value. Many former soldiers had sold their notes at a fraction of face value, believing them to be worthless. He planned to buy back the promissory notes from their current holders. This idea drew loud objections from many who were of the opinion that the notes should be paid back either to the original holder or to both the current and original holder.[67]

Congressional delegations from the Southern states, which had lower or no debts, and whose citizens would effectively pay a portion of the debt of other states if the federal government assumed it, were disinclined to accept the proposal. Additionally, many in Congress argued that the plan was beyond the constitutional power of the new government. James Madison led the effort to block the provision and prevent the plan from gaining approval.[68] Jefferson approved payment of the domestic and foreign debt at par, but not the assumption of state debts.[59] After Hamilton and Jefferson reached the Compromise of 1790, Hamilton's assumption plan was adopted as the Funding Act of 1790.

Later in 1790, Hamilton issued another set of recommendations in his Second Report on Public Credit. The report called for the establishment of a national bank and an excise tax on distilled spirits. Hamilton's proposed national bank would provide credit to fledgling industries, serve as a depository for government funds, and oversee one nationwide currency. In response to Hamilton's proposal, Congress passed the Bank Bill of 1791, establishing the First Bank of the United States.[69] The following year, it passed the Coinage Act of 1792, establishing the United States Mint, and the United States dollar, and regulating the coinage of the United States.[70] Historian Samuel Morison points to Hamilton's Second Report as the event that precipitated Jefferson's change of attitude toward Hamilton and his policies.[71] Jefferson feared that the creation of the national bank would lead to political, economic, and social inequality, with Northern financial interests dominating American society much as aristocrats dominated European society.[72]

In December 1791, Hamilton published the Report on Manufactures, which recommended numerous policies designed to protect U.S. merchants and industries in order to increase national wealth, induce artisans to immigrate, cause machinery to be invented, and employ women and children.[73] Hamilton called for the federally-supervised infrastructure projects, the establishment of state-owned munitions factories and subsidies for privately-owned factories, and the imposition of a protective tariff.[74] Though Congress had adopted much of Hamilton's earlier proposals, his manufacturing proposals fell flat, even in the more-industrialized North, as merchant-shipowners had a stake in free trade.[73] There were also questions raised about the constitutionality of these proposals, and opponents such as Jefferson feared that Hamilton's expansive interpretation of the Taxing and Spending Clause would grant Congress the power to legislate on any subject.

In 1792, with their relationship completely ruptured, Jefferson unsuccessfully tried to convince Washington to remove Hamilton, but Washington largely supported Hamilton's ideas, believing that they had led to social and economic stability.[75] Dissonance over Hamilton's proposals also irrevocably broke the relationship between Washington and Madison, who had served as the president's foremost congressional ally during the first year of his presidency.[76] Opponents of Hamilton and the administration won several seats in the 1792 Congressional elections, and Hamilton was unable to win Congressional approval of his ambitious economic proposals afterward.[74]

The Whiskey Rebellion

Despite the additional import duties imposed by the Tariff of 1790, a substantial federal deficit remained – chiefly due to the federal assumption of state revolution-related debts under the Funding Act.[77] By December 1790, Hamilton believed import duties, which were the government's primary source of revenue, had been raised as high as was feasible.[78] He therefore promoted passage of an excise tax on domestically distilled spirits. This was to be the first tax levied by the national government on a domestic product.[79] Although taxes were politically unpopular, Hamilton believed the whiskey excise was a luxury tax that would be the least objectionable tax the government could levy.[80][81] The tax also had the support of some social reformers, who hoped a "sin tax" would raise public awareness about the harmful effects of alcohol.[82] The Distilled Spirits Duties Act, commonly known as the "Whiskey Act", became law on March 3, 1791, and went into effect on June 1.[83][84]

The tax on whiskey was bitterly and fiercely opposed on the frontier from the day it was passed. Western farmers considered it to be both unfair and discriminatory. As the Lower Mississippi River had been closed to American shipping for nearly a decade, farmers in western Pennsylvania were forced to turn their grain into whiskey. The substantial reduction in volume resulting from the distillation of grain into whiskey greatly reduced the cost to transport their crops to the populous east coast, which was the only place where there were markets for their crops.[77] By the third quarter of 1794, tensions reached a fevered pitch all along the western frontier as the settlers' primary marketable commodity was threatened by the federal taxation measures.[85]

Finally the protests became an armed rebellion. The first shots were fired at the Oliver Miller Homestead in present-day South Park Township, Pennsylvania, about ten miles south of Pittsburgh.[86] As word of the rebellion spread across the frontier, a whole series of loosely organized resistance measures were taken, including robbing the mail, stopping court proceedings, and the threat of an assault on Pittsburgh. One group disguised as women assaulted a tax collector, cropped his hair, coated him with tar and feathers, and stole his horse. Another group bombarded the estate of the tax collector John Neville, a friend of George Washington.[87]

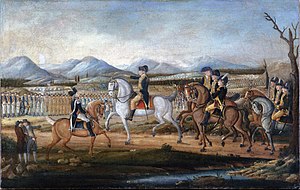

Washington, alarmed by what appeared to be an armed insurrection in Western Pennsylvania, asked his cabinet for written opinions about how to deal with the crisis. The cabinet recommended the use of force, except for Secretary of State Randolph who urged reconciliation.[88] Washington did both – he sent commissioners to meet with the rebels while raising a militia army.[89] When the final report of the commissioners recommended the use of the military to enforce the laws,[90] the president invoked the Militia Law of 1792 to summon the militias of Pennsylvania, Virginia and several other states. The governors sent the troops and Washington took command as Commander-in-Chief, marching into the rebellious districts.[91]

Washington commanded a militia force of 13,000 men, roughly the same size of the Continental Army he had commanded during the Revolutionary War. Under the personal command of Washington, Hamilton and Revolutionary War hero General Henry "Lighthorse Harry" Lee, the army assembled in Harrisburg and marched into Western Pennsylvania (to what is now Monongahela, Pennsylvania) in October 1794. The insurrection collapsed quickly with little violence, and the resistance movements disbanded.[87] The men arrested for rebellion were imprisoned, where one died, while two were convicted of treason and sentenced to death by hanging. Later, Washington pardoned all the men involved.[92][93]

The suppression of the Whiskey Rebellion met with widespread popular approval.[94] This was the first time the new government had been directly opposed, and through a clear show of federal authority, Washington established the principle that federal law is the supreme law of the land,[95] and demonstrated that the federal government had both the ability and willingness to suppress violent resistance to the nation's laws. The government's response to the rebellion was, therefore, viewed by the Washington administration as a success, a view that has generally been endorsed by historians.[96] This also was one of only two times in U.S. history that an incumbent president has personally commanded the military in the field; James Madison would command an army in 1814.[97]

Rise of political parties

Initially, Jefferson and Hamilton enjoyed a friendly working relationship. While never close, they seldom clashed during the first year in the Washington administration. Even so, deep philosophical differences soon caused a rift between them, and finally drove them apart.[98][99] Hamilton believed that a vigorous use of the central government was essential for the task of nation building.[100] He also believed that "a flourishing merchant economy would sow opportunities for all, resulting in a more philanthropic, knowledgeable and enterprising people." In Jefferson's view, centralized government was "simply European-style tyranny waiting to happen again." He idealized the yeoman farmers, for they "controlled their own destinies, and also a republic that, resting on the yeoman farmer, would keep 'alive that sacred fire' of personal liberty and virtue."[98] These differences gained their clearest expression in the debate about the Bank of the United States.[100]

Following their break with the administration, Jefferson and Madison began traveling to various former Anti-Federalist strongholds. At this point, their goal was not to form a political party or even generally oppose Washington, who they continued to admire, but rather to foment opposition to Hamilton's policies. Most Congressmen aligned with either Hamilton or Jefferson during the 1792 elections, but local concerns dominated most campaigns. Hamilton began attacking Jefferson and his followers in the newspapers, calling Jefferson's followers the "Republican Party." The name implicitly accused Jefferson of engaging in partisan behavior, which was disdained by Americans. During this same period, though, Hamilton began to build his own political party. Over time, Jefferson's followers formed the Democratic-Republican Party, while Hamilton's supporters coalesced into the Federalist Party.[101]

While economic policies were the original motivating factor in the growing partisan split, foreign policy also became a factor. Though most Americans supported the French Revolution prior to the Execution of Louis XVI, some of Hamilton's followers began to fear the radical egalitarianism of the revolution as it became increasingly violent. Washington particularly feared British entrance into the war, as he worried that sympathy for France and hatred for Britain would propel the United States into the French Revolutionary Wars, to the ruin of the American economy.[102] In 1793, after Britain entered the French Revolutionary Wars, several Democratic-Republican Societies were formed. These societies, centered on the middle class of several eastern cities, opposed Hamilton's economic policies and supported France. Conservatives came to fear these societies as populist movements that sought to re-make the class order. That same year, the British began attacking American ships that were trading with France, fanning the flames of anti-British sentiment. As Washington continued to seek peace with Great Britain, critics finally began to attack the president himself.[103]

After crushing the Whiskey Rebellion, Washington publicly blamed the Democratic-Republican Societies for the rebellion, and Jefferson began to view Washington as "the head of a party" rather than "the head of a nation." Hamilton's followers, who coalesced into the Federalist Party, were thrilled by Washington's remarks, and the party sought to closely associate itself with Washington. The passage of the Jay Treaty further inflamed partisan warfare, resulting in a hardening of the divisions between the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans.[103] By 1795–96, election campaigns—federal, state and local—were waged primarily along partisan lines between the two national parties, although local issues continued to affect elections, and party affiliations remained in flux.[104]

Constitutional amendments

Although some Anti-Federalists continued to call for a new federal constitutional convention and ridiculed them,[26] Congress approved 12 amendments to the U.S. Constitution on September 25, 1789, establishing specific constitutional guarantees of personal freedoms and rights, clear limitations on the government's power in judicial and other proceedings, and explicit declarations that all powers not specifically delegated to Congress by the Constitution are reserved for the states or the people, and submitted them to the state legislatures for ratification.[105]

By December 15, 1791, 10 of the 12 proposed amendments had been ratified by the requisite number of states (then 11), and became Amendments One through Ten of the Constitution; collectively they are known as the Bill of Rights.[106] [b]

On March 4, 1794, Congress approved an amendment to the United States Constitution clarifying judicial power over foreign nationals, and limiting the ability of citizens to sue states in federal courts and under federal law, and submitted it to the state legislatures for ratification.[109] The Eleventh Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified by the requisite number of states (then 12) on February 7, 1795, to become part of the Constitution.[110]

Slave trade legislation

Congress passed two acts related to the slave trade during the Washington administration: the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, which made it a federal crime to assist an escaping slave, and established the legal system by which escaped slaves would be returned to their masters;[111] and the Slave Trade Act of 1794, which limited the United States' involvement in the transportation of slaves by prohibiting the export of slaves from the country[112]

The Northwest Indian War

|

|

Following adoption of the Land Ordinance of 1785, American settlers began freely moving west across the Allegheny Mountains and into the Indian-occupied lands beyond – land Great Britain had ceded to U.S. "control" at the end of the Revolutionary War (the Northwest Territory). As they did, they encountered unyielding and often violent resistance from a confederation of tribes. In 1789 (before Washington entered office), an agreement that was supposed to address the grievances of the tribes, the Treaty of Fort Harmar, was signed. This new treaty did almost nothing to stop the violence against American pioneers, however, and the following year, Washington directed the United States Army to enforce U.S. sovereignty. Secretary of War Henry Knox ordered Brigadier General Josiah Harmar to launch a major offensive against the Shawnee and Miami Indians living in the region. In October 1790, his force of 1,453 men was assembled near present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana. Harmar committed only 400 of his men under Colonel John Hardin to attack an Indian force of some 1,100 warriors, who easily defeated Hardin's forces. At least 129 soldiers were killed.[113]

Determined to avenge the defeat, the president ordered Major General Arthur St. Clair, who was serving as the governor of the Northwest Territory, to mount a more vigorous effort by the third quarter of 1791. After considerable trouble finding men and supplies, St. Clair was finally ready. At dawn on November 4, 1791, his poorly trained force, accompanied by about 200 camp followers, was camped near the present-day location of Fort Recovery, Ohio, with poor defenses set up around their camp. An Indian force consisting of around 2,000 warriors led by Little Turtle, Blue Jacket, and Tecumseh, struck with swift and overwhelming displays of force, and, paralyzing the Americans with fear, soon overran their poorly prepared perimeter. St. Clair’s army was almost annihilated during the three-hour encounter. The American casualty rate included 632 of 920 soldiers and officers killed (69%) and 264 wounded. Nearly all of the 200 camp followers were slaughtered, for a total of about 832.[114]

British officials in Upper Canada were delighted and encouraged by the success of the Indians, whom they had been supporting and arming for years, and in 1792 Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe proposed that the entire territory, plus a strip of New York and Vermont be erected into an Indian barrier state. While the British government did not take this proposal up, it did inform the Washington administration that it would not relinquish the Northwest forts, even if the U.S. paid its overdue debts.[115][116] Also, early in 1794, the British built a new garrison, Fort Miami, along the Maumee River—about 100 miles (160 km) southwest of Fort Detroit—as a show of presence and support for the resistance.

Outraged by news of the defeat, Washington urged Congress to raise an army capable of conducting a successful offense against the Indian confederacy, which it did in March 1792 – establishing additional Army regiments (the Legion of the United States), adding three-year enlistments, and increasing military pay.[117] The following month the House of Representatives conducted investigative hearings into the debacle. This was the first Special Congressional investigation under the federal Constitution.[118] Afterward, Congress passed two Militia Acts: the first empowered the president to call out the militias of the several states; the second required that every free able-bodied white male citizen of the various states, between the ages of 18 and 45, enroll in the militia of the state in which they reside.[119]

Next, Washington put General "Mad" Anthony Wayne in command of the Legion of the United States and ordered him to launch a new expedition against Western Confederacy. Wayne spent months training his troops at the army's the first formal basic training facility in Legionville, Pennsylvania, in military skills, forest warfare tactics and discipline, then led them west. In late 1793, the Legion began construction of Fort Recovery at the location of St. Clair's defeat; and, on June 30 – July 1, 1794, successfully defended it from an Indian attack led by Little Turtle.[120]

Taking the offensive, the legion marched north through the forest, and, upon reaching the confluence of the Auglaize and Maumee rivers—about 45 miles (72 km) southwest of Fort Miami— on August 8, built Fort Defiance, a stockade with blockhouse bastions. There he offered peace, which was rejected.[115][121] Wayne's soldiers advanced toward Fort Miami and on August 20, 1794 encountered Indian confederacy forces led by Blue Jacket, in what has become known as the Battle of Fallen Timbers. The first assault on Wayne's Legion was successful, but were able to regroup quickly and pressed the attack with a bayonet charge. The cavalry outflanked Blue Jacket's warriors, who were easily routed. They fled towards Fort Miami, but were surprised to find the gates closed against them. The British commander of the fort refused to assist them, unwilling to start a war with the United States. Wayne's army had won a decisive victory. The soldiers spent several days destroying the nearby Indian villages and crops, before withdrawing.[122]

With the door slammed shut on them by their old allies, Native American resistance quickly collapsed.[122] Delegates from the various confederation tribes, 1130 persons total, gathered for a peace conference at Fort Greene Ville in June 1795. The conference lasted for six weeks, resulting, on August 3, 1795 in the Treaty of Greenville between the assembled tribes and the "15 fires of the United States."[115] Under its terms, the tribes ceded most of what is now Ohio for American settlement, recognized the United States (rather than Great Britain) as the ruling power in the region, and turned ten chiefs over to the U.S. government as hostages until all white prisoners were returned in guarantee. This, along with the recently signed Jay Treaty, which provided for the British withdrawal from pre-Revolutionary War forts in the region it had not yet relinquished, solidified U.S. sovereignty over the Northwest Territory.[123]

Foreign affairs

The French Revolution

Public debate

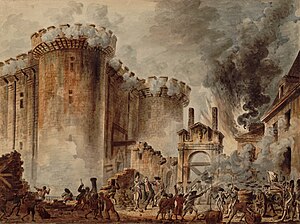

With the Storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, the French Revolution erupted. The American public, remembering the French assistance during the Revolutionary War, was largely enthusiastic, and hoped for democratic reforms that would solidify the existing Franco-American alliance and transform France into a republican ally against aristocratic and monarchical Great Britain.[124] Shortly after the Bastille fell, the main prison key was turned over to the Marquis de Lafayette, a Frenchman who had served under Washington in the American Revolutionary War. In an expression of optimism about the revolution's chances for success, Lafayette sent the key to Washington, who displayed it prominently in the executive mansion.[125] In the Caribbean, the revolution destabilized the French colony of Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti), as it split the government into royalist and revolutionary factions, and aroused the people to demand civil rights for themselves. Sensing an opportunity, the slaves of northern St. Domingue organized and planned a massive rebellion which began on August 22, 1791. Their successful revolution resulted in the establishment of the second independent country in the Americas (after the United States).[126] Soon after the revolt began, the Washington administration, at French request, agreed to send money, arms, and provisions to Saint-Domingue to assist distressed slave-owning colonists.[127] Reacting to reports Haitian slaves slaughtering, many Southerners believed that a successful slave revolt in Haiti would lead to a massive race war in America.[128] American aid to Saint-Domingue formed part of the US repayment of Revolutionary War loans, and eventually amounted to about $400,000 and 1,000 military weapons.[129]

From 1790 to 1794, the French Revolution became increasingly radical.[124] In 1792 the revolutionary government declared war on several European nations, including Great Britain, starting the War of the First Coalition. A wave of bloody massacres spread through Paris and other cities late that summer, leaving over one thousand people dead. On September 21, 1792, France declared itself a republic, and the deposed King Louis XVI was guillotined on January 21, 1793. Then followed a period labeled by some historians as the "Reign of Terror," between the summer of 1793 and the end of July 1794, during which 16,594 official death sentences were carried out against those accused of being enemies of the revolution.[130] Among the executed were persons who had aided the American rebels during the Revolutionary War, such as the navy commander Comte D'Estaing. Lafayette, who was appointed commander-in-chief of the National Guard following the storming of the Bastille, fled France and ended up in captivity in Austria, while Thomas Paine, in France to support the revolutionaries, was imprisoned in Paris.

The political debate in the U.S. over the nature of the revolution exacerbated pre-existing political divisions and resulted in the alignment of the political elite along pro-French and pro-British lines. Thomas Jefferson became the leader of the pro-French faction that celebrated the revolution's republican ideals. Alexander Hamilton led the faction which viewed the revolution with skepticism and sought to preserve existing commercial ties with Great Britain.[124] When news reached America that France had declared war on the British, people were divided on whether the U.S. should enter the war on the side of France. Jefferson and his faction wanted to aid the French, while Hamilton and his followers supported neutrality in the conflict. Jeffersonians denounced Hamilton, Vice President Adams, and even the president as friends of Britain, monarchists, and enemies of the republican values that all true Americans cherish.[131][132] Hamiltonians warned that Jefferson's Republicans would replicate the terrors of the French revolution in America – "crowd rule" akin to anarchy, and the destruction of "all order and rank in society and government."[133]

American neutrality

Although the president, who believed that the United States was too weak and unstable to fight another war with a major European power, wished to avoid any and all foreign entanglements,[134] a sizable portion of the American public was ready to help the French and their fight for "liberty, equality, and fraternity." In the days immediately following Washington's second inauguration, the revolutionary government of France sent diplomat Edmond-Charles Genêt, called "Citizen Genêt," to America. Genêt's mission was to drum up support for the French cause. Genêt issued letters of marque and reprisal to American ships so they could capture British merchant ships.[135] He attempted to turn popular sentiment towards American involvement in the French war against Britain by creating a network of Democratic-Republican Societies in major cities.[136]

Washington was deeply irritated by this subversive meddling, and when Genêt allowed a French-sponsored warship to sail out of Philadelphia against direct presidential orders, Washington demanded that France recall Genêt. However, by this time the revolution had taken a more violent approach and Genêt would have been executed had he returned to France. He appealed to Washington, and Washington allowed him to remain, making him the first political refugee to seek sanctuary in the United States.[137]

During the Genêt episode, Washington, after consulting his Cabinet, issued a Proclamation of Neutrality on April 22, 1793. In it he declared the United States neutral in the conflict between Great Britain and France. He also threatened legal proceedings against any American providing assistance to any of the warring countries. Washington eventually recognized that supporting either Great Britain or France was a false dichotomy. He would do neither, thereby shielding the fledgling U.S. from, in his view, unnecessary harm.[138]

The public had mixed opinions about Washington's Proclamation of Neutrality. Those who supported Madison and Jefferson were far more likely to be in support of the French Revolution, as they saw it as an opportunity for a nation to achieve liberty from tyrannical rule. However, there were a number of merchants who were extremely happy that the President decided to remain impartial to the revolution. They believed that if the government took a stance on the war, it would ruin their trade relations with the British completely. This economic element was a primary reason for many federalist supporters wanting to avoid increased conflict with the British. Hamilton supported the Proclamation of Neutrality, defending it under the pseudonym "Pacificus."[139] He encouraged Washington to issue the proclamation, lecturing him about the need for a "continuance of the peace, the desire of which may be said to be both universal and ardent."[140]

Relations with Great Britain

Seizures and economic retaliation

Upon going to war against France, the British Royal Navy began intercepting ships of neutral countries bound for French ports. The French imported large amounts of American foodstuffs, and the British hoped to starve the French into defeat by intercepting these shipments.[141] In November 1793 the British government widened the scope of these seizures to include any neutral ships trading with the French West Indies, including those flying the American flag.[142] By the following March, over 250 U.S. merchant ships had been seized and their crews impressed.[143] Americans were outraged, and angry protests erupted in several cities.[144] Many Jeffersonians in Congress demanded a declaration of war, but Congressman James Madison instead called for strong economic retaliation, including an embargo on all trade with Britain.[145] Further inflaming anti-British sentiment in Congress, news arrived while the matter was under debate that the Governor General of British North America, Lord Dorchester, had made an inflammatory speech inciting the Indians in the Northwest Territory against the Americans.[142][145][c]

Congress responded to these "outrages" by passing a 30-day embargo (March 26 – April 26, 1794) on all shipping, foreign and domestic, in American harbors, which Washington signed into law.[143] In the meantime, the British government had issued an order in council mitigating effects of the November order. This policy change did not defeat the whole movement for commercial retaliation, but it cooled passions somewhat. The embargo was later renewed for a second month, but then permitted to expire.[147] The President's strong inclination in response to British provocations was to seek a diplomatic solution. Taking advantage of the apparent change in British attitude, he named Supreme Court Chief Justice John Jay as special envoy to Great Britain in an effort to head off war.[148][d] This appointment provoked the ire of Jeffersonians. Although confirmed by a comfortable margin in the U.S. Senate (18–8), debate on the nomination was bitter.[152]

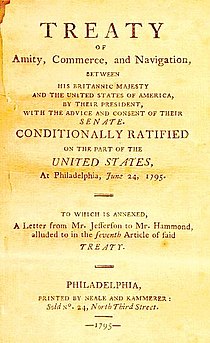

Jay Treaty

Jay was instructed by Alexander Hamilton to seek compensation for seizure of American ships and to clarify the rules governing British seizure of neutral ships. He was also to insist that the British relinquish their posts in the Northwest. In return, the U.S. would take responsibility for pre-Revolution debts owed to British merchants and subjects. He also asked Jay, if possible, to seek limited access for American ships to the British West Indies.[142] Jay and the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Grenville, began negotiations on July 30, 1794. The treaty that emerged several weeks later, commonly known as the Jay Treaty, was, in Jay's words "equal and fair."[153] Both sides achieved many objectives; several issues were sent to arbitration. For the British, America remained neutral and economically grew closer to Britain. The Americans also guaranteed favorable treatment to British imports. In return, the British agreed to evacuate the western forts, which they had been supposed to do by 1783. They also agreed to open their West Indies ports to smaller American ships, allow small vessels to trade with the French West Indies, and set up a commission that would adjudicate American claims against Britain for seized ships, and British claims against Americans for debts incurred before 1775. However, the treaty contained neither concessions on impressment nor statement of rights for American sailors. Another commission was later established to settle boundary issues.[154]

Once the treaty arrived in Philadelphia in March 1795, Washington—who had misgivings about the treaty's terms—kept its contents confidential until June, when a special session of the Senate would convene to give its advice and consent. Peter Trubowitz writes that during these several months Washington wrestled with "a strategic dilemma," balancing geopolitics and domestic politics. "If he threw his support behind the treaty, he risked destroying his fragile government from within due to partisan rage. If he shelved the treaty to silence his political detractors, there would likely be war with Great Britain, which had the potential to destroy the government from the outside."[155] Submitted on June 8, debate on the treaty's 27 articles was carried out in secret, and lasted for more than two weeks.[156] Republican senators, who wanted to pressure Britain to the brink of war,[157] denounced the Jay Treaty as an insult to American prestige, and a repudiation of the 1778 treaty and military support with France; New York's Aaron Burr argued point-by-point why the whole agreement should be renegotiated. On June 24, the Senate approved the treaty by a vote of 20–10 – the precise two-thirds majority vote necessary for ratification.[156]

Although the Senate hoped to keep the treaty secret until Washington had decided whether or not to sign it, it was leaked to a Philadelphia editor who printed it in full on June 30.[156] Within a few days the whole the country knew the terms of the agreement, and, in the words of Samuel Morison, "a howl or rage went up that Jay had betrayed his country."[158] The reaction to the treaty was the most negative in the South. Southern planters, who owed the pre-Revolution debts to the British and who were now not going to collect for the slaves lost to them, viewed it as a great indignity. As a result, the Federalists lost most of the support they had among planters.[159] Protests, organized by Republicans, included petitions, incendiary pamphlets, and a series of public meetings held in the larger cities, each of which addressed a memorial to the president.[160]

There was a temporary lull in the Jay Treaty furor after Washington signed it on August 24. The following year, however, it flared up again, when the House of Representatives inserted itself into the debate. This time the fight was not only over the merits of the treaty, but also about whether the House had the power under the Constitution to refuse to appropriate the money necessary for a treaty already ratified by the Senate and signed by the president.[160] Citing its constitutional fiscal authority (Article I, Section 7), the House requested that the president turn over all documents that related to the treaty, including his instructions to Jay, all correspondence, and all other documents relating to the treaty negotiations. He refused to do so, invoking what later became known as executive privilege,[95] and insisted that the House did not have the Constitutional authority to block treaties.[156][161] A contentious debate ensued, during which, Washington's most vehement opponents in the House went so far as to publicly call for his impeachment.[159] Through it all, Washington responded to his critics by using his prestige, political skills, and the power of office in a sincere and straightforward fashion to broaden public support for his stance.[162] On April 30, the House voted 51–48 to approve the requisite treaty funding.[156] Jeffersonians carried their campaign against the treaty and "pro-British Federalist policies" into the political campaigns (both state and federal) of 1796,[163] where the political divisions marking the First Party System became crystallized.

Internationally, the treaty pushed American diplomatic relations away from France and towards Great Britain, as the French government concluded that it violated the Franco-American treaty of 1778, and that the U.S. government had accepted the treaty against the overwhelming public sentiment against it.[163] This set up a series of diplomatic and political conflicts over the ensuing four years, culminating in what became known as the Quasi-War.[156][164] The Jay Treaty also helped ensure American control of its own frontier lands. After the signing of treaty, the British withdrew their support from several Native Americans tribes, while the Spanish, fearing that the Jay Treaty signaled the creation of an Anglo-American alliance, sought to appease the United States.[165]

Barbary pirates

Following the end of the Revolutionary War the ships of the Continental Navy were gradually disposed of, and their crews disbanded. The frigate Alliance, which had fired the last shots of the war in 1783, was also the last ship in the Navy. Many in the Continental Congress wanted to keep the ship in active service, but the lack of funds for repairs and upkeep, coupled with a shift in national priorities, eventually prevailed over sentiment. The ship was sold in August 1785, and the navy disbanded.[166][167] At around the same time American merchant ships in the Western Mediterranean and Southeastern North Atlantic began having problems with pirates operating from ports along North Africa's so-called Barbary Coast – Algiers, Tripoli, and Tunis. In 1784–85, Algerine pirate ships seized two American ships (Maria and Dauphin) and held their crews for ransom.[168][169] Thomas Jefferson, then Minister to France, suggested an American naval force to protect American shipping in the Mediterranean, but his recommendations were initially met with indifference, as were later recommendations of John Jay, who proposed building five 40-gun warships.[168][169] Beginning late in 1786, the Portuguese Navy began blockading Algerian ships from entering the Atlantic Ocean through the Strait of Gibraltar, which provided temporary protection for American merchant ships.[168][170]

Piracy against American merchant shipping had not been a problem before 1776, when ships from the Thirteen Colonies were protected by British warships and treaties (nor was it a problem during the revolution, as the French Navy assumed the responsibility as part of the alliance treaty). Only after the U.S. achieved its independence did Barbary pirates begin capturing American ships, and demanding ransom or tribute.[170] Additionally, once the French Revolution started, the British Navy began intercepting American merchant ships suspected of trading with France, and France began intercepting American merchant ships suspected of trading with Great Britain. Defenseless, the American government could do little to resist.[171] Even given these events there was great resistance in Congress to formation of a naval force. Opponents asserted that payment of tribute to the Barbary states was a better solution than building a navy, which they argued would only lead to calls for a navy department, and the staff to operate it. This would then lead to more appropriations of funds, which would eventually spiral out of control, giving birth to a "self-feeding entity."[172][173] Then, in 1793, a truce negotiated between Portugal and Algiers ended Portugal's blockade of the Strait of Gibraltar, freeing the Barbary pirates to roam the Atlantic. Within months, they had captured 11 American vessels and more than a hundred seamen.[166][170]

The cumulation of all these events led Washington to request Congress to establish a standing navy.[174][175] After a contentious debate, Congress passed the Naval Armament Act on March 27, 1794, authorizing construction of six frigates (to be built by Joshua Humphreys). These ships were the first ships of what eventually became the present-day United States Navy.[166][172] Soon afterward, Congress also authorized funds to obtain a treaty with Algiers and to ransom Americans held captive (199 were alive at that time, including a few survivors from the Maria and the Dauphin). Ratified in September 1795, the final cost of the return of those held captive and peace with Algiers was $642,000, plus $21,000 in annual tribute. The president was unhappy with the arrangement, but realized the U.S. had little choice but to agree to it.[176] Treaties were also concluded with Tripoli, in 1796, and Tunis in 1797, each carrying with it an annual U.S. tribute payment obligation for protection from attack.[177] The new Navy would not be deployed until after Washington left office; the first two frigates completed were: United States, launched May 10, 1797; and Constitution, launched October 21, 1797.[178]

Relations with Spain

In the late 1780s the state of Georgia grew eager to firm up its trans-Appalachian land claim, and to fill the great demand for land to develop. The territory claimed by Georgia, which it called the "Yazoo lands," ran west from the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River, and included most of the present-day states of Alabama and Mississippi (between 31° N and 35° N). The southern portion of this region was also claimed by Spain as part of Spanish Florida. One of Georgia's efforts to accomplish its goals for the region, a 1794 plan developed by governor George Mathews and the Georgia General Assembly, became a major political scandal, known as the Yazoo land scandal.

Spain had, since 1763, controlled the lands west of the Mississippi River, Spanish Louisiana, plus New Orleans on its east bank. Great Britain, between 1763 and 1783, controlled the lands east of the Mississippi, British Florida, north from the Gulf of Mexico. Spain gained possession of British Florida south of 31° N and claimed the rest of it – north to 32° 22′ (the junction of the Mississippi and Yazoo Rivers). Thereafter, Spain attempted to slow the migration of American settlers into the region, and to lure those already there to secede from the United States.[179] Toward this end, in 1784 the Spanish closed New Orleans to American goods coming down the Mississippi, which was the only viable outlet for the goods produced by many American settlers,[180] and also began selling weapons to the Indian tribes in the Yazoo.

After Washington issued his 1793 Proclamation of Neutrality he became concerned that Spain, which later that year joined Britain in war against France, might work in consort to incite insurrection in the Yazoo against the U.S., using the opening of trade on the Mississippi as an enticement.[180] At that same time though, mid-1794, Spain was attempting to extract itself from its alliance with the British, and to restore peace with France. As Spain's prime minister, Manuel de Godoy, was attempting to do so, he learned of John Jay's mission to London, and became concerned that those negotiations would result in an Anglo-American alliance and an invasion of Spanish possessions in North America. Sensing the need for rapprochement, Godoy sent a request to the U.S. government for a representative empowered to negotiate a new treaty; Washington sent Thomas Pinckney to Spain in June of 1795.[181]

Eleven months after the signing of the Jay Treaty, the United States and Spain agreed to the Treaty of San Lorenzo, also known as Pinckney's Treaty. Signed on October 27, 1795, the treaty established intentions of peace and friendship between the U.S. and Spain; established the southern boundary of the U.S. with the Spanish colonies of East Florida and West Florida, with Spain relinquishing its claim on the portion of West Florida north of the 31st parallel; and established the western U.S. border as being along the Mississippi River from the northern U.S. to the 31st parallel.[182]

Perhaps most importantly, Pinckney's Treaty granted both Spanish and American ships unrestricted navigation rights along the entire Mississippi River, as well as duty-free transport for American ships through the Spanish port of New Orleans, opening much of the Ohio River basin for settlement and trade. Agricultural produce could now flow on flatboats down the Ohio River to the Mississippi and on to New Orleans and Europe. Spain and the United States further agreed to protect the vessels of the other party anywhere within their jurisdictions and to not detain or embargo the other's citizens or vessels.[183]

The final treaty also voided Spanish guarantees of military support that colonial officials had made to Native Americans in the disputed regions, greatly weakening those communities’ ability to resist encroachment upon their lands.[181] The treaty represented a major victory for Washington administration, and placated many of the critics of the Jay Treaty. It also enabled and encouraged American settlers to continue their movement west, by making the frontier areas more attractive and lucrative.[184] The region that Spain relinquished its claim to through the treaty was organized by Congress as Mississippi Territory on April 7, 1798.

Election of 1792

As the presidential election of 1792 approached, Washington, pleased with the progress his administration had made in establishing a strong, stable federal government,[185] was planning to retire rather then seek a second term. He complained of old age, sickness, the in-fighting plaguing his cabinet, and the increasing hostility of the partisan press.[186] However, the members of his cabinet—especially Jefferson and Hamilton—worked diligently through the summer and fall to persuade Washington not to retire.[187] They apprised him of the potential impact the French Revolutionary Wars might have on the country, and insisted that only someone with his popularity and moderation could lead the nation effectively during the volatile times ahead.[4][188] In the end, "Washington never announced his candidacy in the election of 1792," writes historian John Ferling, "he simply never said that he would not consider a second term."[189]

The 1792 elections were the first ones in U.S. history to be contested on anything resembling a partisan basis. In most states, the congressional elections were recognized in some sense as a "struggle between the Treasury department and the republican interest," to use the words of Jefferson strategist John Beckley.[190] Because few doubted that Washington would receive the greatest number of electoral votes, the vice presidency became a focus of popular attention. The speculation here also tended to be organized along partisan lines – Hamiltonians supported Adams and Jeffersonians favored New York governor George Clinton. Both however were technically candidates for president competing against Washington, as electoral rules of the time required each presidential elector to cast two votes without distinguishing which was for president and which for vice president. The recipient of the most votes would then become president, and the runner-up vice president.

Washington was unanimously reelected president, receiving 132 electoral votes (one from each elector), and Adams was reelected vice president, receiving 77 votes. The other 55 electoral votes were divided among: George Clinton (50), Thomas Jefferson (4), and Aaron Burr (1).[186]

Washington's second inauguration took place in the Senate Chamber of Congress Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (the first at this site) on March 4, 1793. The presidential oath of office was administered by Supreme Court associate justice William Cushing. Washington's inaugural address was just 135 words, the shortest to date.[191] This inauguration was brief and simple, a sharp contrast to the extravaganza four years earlier, which, in the eyes of many, had all the trappings of a monarchical coronation.[189]

Although his second term began simultaneously with Washington's, John Adams was sworn into office for that term on December 2, 1793 in the Senate Chamber of Congress Hall. The vice presidential oath was administered by the president pro tempore of the Senate John Langdon.[21]

Presidential residences and tours

Residences

Washington lived in three executive mansions during his presidency:

| Residence and location | Time span | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Samuel Osgood House 3 Cherry Street New York, New York |

– February 23, 1790 |

Congress leased the house from Samuel Osgood for a sum of $845 per year.[192][193] |

|

Alexander Macomb House 39–41 Broadway New York, New York |

– August 30, 1790 |

The "first family" moved into this larger and more conveniently located house when Elénor-François-Elie, Comte de Moustier returned to France.[193] |

|

President's House 524-30 Market Street Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

– March 10, 1797[194][195] |

The owner of nine slaves, Washington circumvented Pennsylvania's Gradual Abolition law by rotating them between Philadelphia and Mount Vernon.[196] |

Tours

Washington made three major tours around the country. The first was to New England (1789), the second to Rhode Island and New York City (1790), and the third to the Southern states (1791).[197]

His first trip was to New England. His main goals were to educate himself about "the principal character and internal circumstances" of the different regions of the country, as well as meet "well informed persons, who might give him useful information and advice on political subjects." In addition, he scouted out locations for canals and other internal improvements, as well as learning the popular opinion on multiple issues. His first stop along the trip was to New Haven, Connecticut. From New Haven, he traveled through Massachusetts on the way to Boston. In Boston, a large fanfare greeted him. From Boston, Washington traveled north, stopping in Marblehead and Salem, Massachusetts. About a week after being in Boston, he traveled north to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and circled back to New York, stopping in Waltham and Lexington. The trip was a success, serving to consolidate his popularity and improve his health.[198]

After Rhode Island ratified the Constitution, Washington promptly took another tour to visit it. Along with Jefferson and New York governor George Clinton, he first stopped in Newport, Rhode Island, then traveled to Providence, Rhode Island. On August 22, 1790, Washington returned to New York City.[199]

In 1791, Washington left on his third trip, to the South, largely to promote national unity amid uproar over Hamilton's economic plan, as well as slavery. The trip began on March 20, 1791, when Washington and a small group of aides began sailing down the Severn River. After sailing through a large storm, they arrived in Annapolis. From Annapolis he traveled to Mount Vernon, and from there to Colchester, Virginia, to Richmond, Virginia. After leaving Richmond, he went to Petersburg, than Emporia, Virginia. He left Virginia and went to Craven County, North Carolina, then New Bern. Washington's last stop in North Carolina was Wilmington, which upon leaving he promptly arrived in Georgetown, South Carolina, subsequently travelling to Charleston. After South Carolina, Washington arrived in Georgia, going to (among others) Augusta. In late May, Washington turned around, stopping at many Revolutionary War battle sites. On July 11, 1791, they arrived back at Mount Vernon.[200][201]

States joining the Union

When the federal government began operations under the new form of government on March 4, 1789, two (of the 13) states were ineligible to participate as they had not yet ratified the Constitution. Both did so while Washington was in office, thereby joining the new Union: North Carolina, November 21, 1789;[202] and Rhode Island, May 29, 1790.[203]

Three new states were admitted to the Union (each on an equal footing with the existing states) while Washington was in office: Vermont, March 4, 1791;[204][e] Kentucky, June 1, 1792;[206][f] and Tennessee, June 1, 1796[207][g]

Farewell Address and election of 1796

Farewell Address

As his second term entered its final year in 1796, Washington was in poor health, exhausted from years of internal squabbling among members of his cabinet and external attacks in the press, and he was ready to retire to Mount Vernon. Although many Americans had been expecting or anticipating that Washington would serve a third term, that spring he decided not to, and began drafting his Farewell Address to "friends and fellow-citizens." It was a momentous decision, as at that time in the history of western civilization national leaders rarely relinquished their titles voluntarily,[208] In making the announcement and then following through on it, Washington established a precedent for the democratic transfer of executive power.[209] His departure from office after two terms set a pattern for subsequent U.S. presidents,[h] and provided future generations of elected leaders with a lesson in democratic conduct through both word and deed.[208][209]