Anti-Irish sentiment: Difference between revisions

m Citation for Fried's academic background |

add details and citations |

||

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

[[File:NINA-nyt.JPG|thumb|300px|left|One of two NINA ("No Irish Need Apply") ads found in ''[[The New York Times]]'' between 1851 and 1923.<ref name="Jensen"/>]]After 1860 many Irish sang songs about signs reading "HELP WANTED – NO IRISH NEED APPLY"; these signs came to be known as "NINA signs." (This is sometimes written as "IRISH NEED NOT APPLY" and referred to as "INNA signs").<ref name="Jensen">Jensen, Richard (2002, revised for web 2004) "[http://tigger.uic.edu/~rjensen/no-irish.htm 'No Irish Need Apply': A Myth of Victimization]". ''Journal of Social History'' issn.36.2 pp.405–429</ref> The 1862 song, "No Irish Need Apply", was inspired by NINA signs in London. Later Irish Americans adapted the lyrics, and the songs perpetuated the belief among Irish Americans that they were discriminated against.<ref name="Jensen"/> |

[[File:NINA-nyt.JPG|thumb|300px|left|One of two NINA ("No Irish Need Apply") ads found in ''[[The New York Times]]'' between 1851 and 1923.<ref name="Jensen"/>]]After 1860 many Irish sang songs about signs reading "HELP WANTED – NO IRISH NEED APPLY"; these signs came to be known as "NINA signs." (This is sometimes written as "IRISH NEED NOT APPLY" and referred to as "INNA signs").<ref name="Jensen">Jensen, Richard (2002, revised for web 2004) "[http://tigger.uic.edu/~rjensen/no-irish.htm 'No Irish Need Apply': A Myth of Victimization]". ''Journal of Social History'' issn.36.2 pp.405–429</ref> The 1862 song, "No Irish Need Apply", was inspired by NINA signs in London. Later Irish Americans adapted the lyrics, and the songs perpetuated the belief among Irish Americans that they were discriminated against.<ref name="Jensen"/> |

||

Historians have hotly debated the issue of anti-Irish job discrimination in the United States. Some insist that the "No Irish need apply" signs were common, but one scholar, Richard Jensen, argues that anti-Irish job discrimination was not a significant factor in the United States, these signs and print advertisements being most commonly posted by the limited number of early 19th-century English immigrants to the United States who shared the prejudices of their homeland.<ref name="Jensen"/>{{-}} Subsequent research by Rebecca A. Fried, |

Historians have hotly debated the issue of anti-Irish job discrimination in the United States. Some insist that the "No Irish need apply" signs were common, but one scholar, Richard Jensen, argues that anti-Irish job discrimination was not a significant factor in the United States, these signs and print advertisements being most commonly posted by the limited number of early 19th-century English immigrants to the United States who shared the prejudices of their homeland.<ref name="Jensen"/>{{-}} Subsequent research by Rebecca A. Fried, an 8th grade student from Washington D.C.,<ref>http://www.longislandwins.com/columns/detail/high_school_student_proves_professor_wrong_when_he_denied_no_irish_need_app</ref> discovered additional instances of the restriction used in advertisements for many different types of positions, including "“clerks at stores and hotels, bartenders, farm workers, house painters, hog butchers, coachmen, bookkeepers, blackers, workers at lumber yards, upholsterers, bakers, gilders, tailors, and papier mache workers, among others.” While the greatest number of NINA instances occurred in the 1840s, and may be from a single advertiser, Fried found evidence for its continued use throughout the subsequent century, with the most recent dating to 1909 in Butte, Montana.<ref>Fried, Rebecca A. (2015) "No Irish Need Deny: Evidence for the Historicity of NINA Restrictions in Advertisements and Signs" ''Journal of Social History'' 48. Accessed 17 July 2015. doi: 10.1093/jsh/shv066. |

||

------- In addition to job postings, the article also surveys evidence relevant to several of Jensen's subsidiary arguments, including lawsuits involving NINA publications, NINA restrictions in housing solicitations, Irish-American responses to NINA advertisements, and the use of NINA advertisements in Confederate propaganda", and concludes (per the abstract) that "Jensen's thesis about the highly limited extent of NINA postings requires revision", and that "the earlier view of historians generally accepting the widespread reality of the NINA phenomenon is better supported by the currently available evidence."</ref> |

------- In addition to job postings, the article also surveys evidence relevant to several of Jensen's subsidiary arguments, including lawsuits involving NINA publications, NINA restrictions in housing solicitations, Irish-American responses to NINA advertisements, and the use of NINA advertisements in Confederate propaganda", and concludes (per the abstract) that "Jensen's thesis about the highly limited extent of NINA postings requires revision", and that "the earlier view of historians generally accepting the widespread reality of the NINA phenomenon is better supported by the currently available evidence."</ref> Fried found one window sign in the entire 19th century: it was for a patronage job at a police station in a small town in 1883. Examining the daily press, she reports that from all the newspapers from Chicago 1850-1900 there were 3 NINA ads, from New York newspapers 6 ads, and 8 in Boston. Fried says, "Jensen’s results were corroborated in 2013 by Donald MacRaild."<ref> Donald M. MacRaild, “‘No Irish Need Apply’: The Origins and Persistence of a Prejudice,” ''Labour History Review'' 78 (2013): 269-299)</ref> Fried reports that historians who have endorsed Jensen's results include Tyler Anbinder,<ref>Tyler Anbinder, “Nativism and Prejudice Against Immigrants,” in ''A Companion to American Immigration,'' ed. Reed Ueda (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2006), 188-89.</ref>, Cathy Stanton,<ref>Cathy Stanton, ''The Lowell Experiment: Public History in a Post-Industrial City'' (University of Massachusetts Press, 2006), pp 79 and 268 n.8. </ref> Augusto Ferraiuolo,<ref> Augusto Ferraiuolo, ''Religious Festive Practices in Boston's North End: Ephemeral Identities in an Italian American Community'' (State University of New York Press, 2009), pp 238-39 n.21)</ref> and David A. Wilson.<ref> David A. Wilson, “Introduction,” in Wilson, ed., ''Irish Nationalism in Canada, (McGill-Queens University Press, 2009), p 5.</ref>. Fried says, “Jensen’s conclusions about these facts have coalesced into something like a ‘consensus’ view.” |

||

===20th century=== |

===20th century=== |

||

Revision as of 17:37, 5 August 2015

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

Anti-Irish sentiment or Hibernophobia may refer to or include racism, oppression, persecution, discrimination, hatred or fear of Irish people as an ethnic group or nation, whether directed against Ireland in general or against Irish emigrants and their descendants in the Irish diaspora.

It is traditionally rooted in the medieval period, and is also evidenced in Irish emigration to North America, Australasia, and Great Britain. Anti-Irish feeling can include both social and cultural discrimination in Ireland itself, such as sectarianism or cultural religious political conflicts in the Troubles of Northern Ireland.

Discrimination towards Irish Travellers, an Irish minority group, is evident in both the Republic of Ireland[1][2] and the United Kingdom.[3]

Perspective

The negative stereotyping of the Irish began with the Norman propagandist Giraldus Cambrensis also known as Gerald of Wales. He wrote disparagingly of the Irish to justify the Norman invasion of Ireland. "Gerald was seeking promotion by Henry II within the English church. His history was therefore written to create a certain effect—of supporting Henry II's claims to Ireland."[4]

Hostility increased towards the Irish who steadfastly remained Roman Catholic, in spite of coercive force by Henry VIII and his administration – as well as subsequent rulers to convert the Irish nation to Protestantism.[5] Thus, a situation unusual in Western Europe developed where the religious majority were ruled over by a religious minority. Religious minorities were discriminated against all over Europe but in Ireland the majority of the people suffered oppression discrimination from the minority ruling class. This led to endless social conflict, and, thus, the consequent dehumanizing of the vanquished Irish.

Many concerted efforts were made by English Protestant churches to evangelize the Irish but each attempt ended in failure and they publicly blamed their failures on the people they were trying to convert. In the middle of the 19th century when a great famine (caused by economic mismanagement and disrespect) struck, many saw it as God punishing the Irish for not converting to Protestantism.[6]

Therefore most of the negative stereotyping of the Irish is rooted in the politics of cuius regio, eius religio, a principle that held that every ruler had the right to dictate what religion their subjects should believe in.

Middle Ages to Early Modern Era

Negative English attitudes towards the Gaelic Irish and their culture date as far back as the reign of Henry II of England. In 1155 Pope Adrian IV issued the papal bull called Laudabiliter, that gave Henry permission to conquer Ireland as a means of strengthening the Papacy's control over the Irish Church.[7] Pope Adrian called the Irish a "rude and barbarous" nation. Thus, the Norman invasion of Ireland began in 1169 with the backing of the Papacy. Pope Alexander III, who was Pope at the time of the invasion, ratified the Laudabiliter and gave Henry dominion over Ireland. He likewise called the Irish a "barbarous nation" with "filthy practises".[8]

Gerald of Wales accompanied King Henry's son, John, on his 1185 trip to Ireland. As a result of this he wrote Topographia Hibernica ("Topography of Ireland") and Expugnatio Hibernia ("Conquest of Ireland"), both of which remained in circulation for centuries afterwards. Ireland, in his view, was rich; but the Irish were backward and lazy:

They use their fields mostly for pasture. Little is cultivated and even less is sown. The problem here is not the quality of the soil but rather the lack of industry on the part of those who should cultivate it. This laziness means that the different types of minerals with which hidden veins of the earth are full are neither mined nor exploited in any way. They do not devote themselves to the manufacture of flax or wool, nor to the practice of any mechanical or mercantile act. Dedicated only to leisure and laziness, this is a truly barbarous people. They depend on their livelihood for animals and they live like animals.[9]

Gerald was not atypical, and similar views may be found in the writings of William of Malmesbury and William of Newburgh. When it comes to Irish marital and sexual customs Gerald is even more biting: "This is a filthy people, wallowing in vice. They indulge in incest, for example in marrying – or rather debauching – the wives of their dead brothers". Even earlier than this Archbishop Anselm accused the Irish of wife swapping, "exchanging their wives as freely as other men exchange their horses".

One will find these views echoed centuries later in the words of Sir Henry Sidney, twice Lord Deputy of Ireland during the reign of Elizabeth I, and in those of Edmund Tremayne, his secretary. In Tremayne's view the Irish "commit whoredom, hold no wedlock, ravish, steal and commit all abomination without scruple of conscience".[10] In A View of the Present State of Ireland, circulated in 1596 but not published until 1633, the English official and renowned poet Edmund Spenser wrote "They are all papists by profession but in the same so blindingly and brutishly informed that you would rather think them atheists or infidels". In a "Brief Note on Ireland," Spenser argued that "Great force must be the instrument but famine must be the means, for till Ireland be famished it cannot be subdued. . . There can be no conformitie of government whereis no conformitie of religion. . . There can be no sounde agreement betwene twoe equall contraries viz: the English and Irish".[11]

This "civilising mission" embraced any manner of cruel and barbaric methods to accomplish its end goal. For instance, in 1305 Piers Bermingham received a financial bonus and accolades in verse after beheading thirty members of the O'Connor clan and sending them to Dublin. In 1317 one Irish chronicler opined that it was just as easy for an Englishman to kill an Irishman or English women to kill an Irish women as he/she would a dog. The Irish were thought of as the most barbarous people in Europe, and such ideas were modified to compare the Scottish Highlands or Gàidhealtachd where traditionally Scottish Gaelic is spoken to medieval Ireland.[12]

Modern period

In the Early Modern period following the advent of Protestantism in Great Britain, the Irish people suffered both social and political oppression for refusing to renounce Catholicism. This discrimination sometimes manifested itself in areas with large Puritan or Presbyterian populations such as the northeastern parts of Ireland, the Central Belt of Scotland, and parts of Canada.[13][14][15] Thinly veiled nationalism under the guise of religious conflict has occurred in both the UK and Ireland.[16]

Anti-Irish sentiment is found in works by several 18th-century writers such as Voltaire, who depicted the Catholic Irish as savage and backward, and defended British rule in the country.[17]

19th century

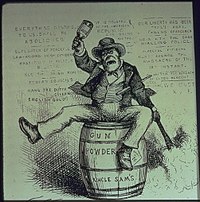

Irish racism in Victorian Britain and 19th century United States included the stereotyping of the Irish as alcoholics, and implications that they monopolised certain (usually low-paying) job markets.[citation needed] They were often called "white Negroes." Throughout Britain and the US, newspaper illustrations and hand drawings depicted a prehistoric "ape-like image" of Irish faces to bolster evolutionary racist claims that the Irish people were an "inferior race" as compared to Anglo-Saxons.[18]

Similar to other immigrant populations, they were sometimes accused of cronyism and subjected to misrepresentations of their religious and cultural beliefs. The Irish were labelled as practising Pagans and in that time (19th century), anyone not being a "Christian" in a traditional British sense was deemed "immoral" and "demonic". Irish Catholics were particularly singled out, and Irish mythology, folklore, and customs were ridiculed.[18]

In Liverpool where many Irish immigrants settled following the Great Famine, anti-Irish prejudice was widespread. The sheer numbers of people coming across the Irish sea and settling in the poorer districts of the city led to physical attacks and it became common practice for those with Irish accents or even Irish names to be barred from jobs, public houses and employment opportunities.

British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli stated publicly, "The Irish hate our order, our civilization, our enterprising industry, our pure religion. This wild, reckless, indolent, uncertain and superstitious race have no sympathy with the English character. Their ideal of human felicity is an alternation of clannish broils and coarse idolatry. Their history describes an unbroken circle of bigotry and blood."[19]

Nineteenth-century Protestant American "Nativist" discrimination against Irish Catholics reached a peak in the mid-1850s when the Know Nothing Movement tried to oust Catholics from public office. Much of the opposition came from Irish Protestants, as in the 1831 riots in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[20]

During the 1830s, riots broke out in rural areas among rival labour teams from different parts of Ireland, and between Irish and "native" American work teams competing for construction jobs.[21]

Irish Catholics were isolated and marginalised by society. Both ministers and priests discouraged intermarriage between Catholics and Protestants. In addition, the creation of a parochial school system and numerous colleges affiliated with the Church tended to compound rather than alleviate anti-Catholic discrimination.[22]

After 1860 many Irish sang songs about signs reading "HELP WANTED – NO IRISH NEED APPLY"; these signs came to be known as "NINA signs." (This is sometimes written as "IRISH NEED NOT APPLY" and referred to as "INNA signs").[23] The 1862 song, "No Irish Need Apply", was inspired by NINA signs in London. Later Irish Americans adapted the lyrics, and the songs perpetuated the belief among Irish Americans that they were discriminated against.[23] Historians have hotly debated the issue of anti-Irish job discrimination in the United States. Some insist that the "No Irish need apply" signs were common, but one scholar, Richard Jensen, argues that anti-Irish job discrimination was not a significant factor in the United States, these signs and print advertisements being most commonly posted by the limited number of early 19th-century English immigrants to the United States who shared the prejudices of their homeland.[23]

Subsequent research by Rebecca A. Fried, an 8th grade student from Washington D.C.,[24] discovered additional instances of the restriction used in advertisements for many different types of positions, including "“clerks at stores and hotels, bartenders, farm workers, house painters, hog butchers, coachmen, bookkeepers, blackers, workers at lumber yards, upholsterers, bakers, gilders, tailors, and papier mache workers, among others.” While the greatest number of NINA instances occurred in the 1840s, and may be from a single advertiser, Fried found evidence for its continued use throughout the subsequent century, with the most recent dating to 1909 in Butte, Montana.[25] Fried found one window sign in the entire 19th century: it was for a patronage job at a police station in a small town in 1883. Examining the daily press, she reports that from all the newspapers from Chicago 1850-1900 there were 3 NINA ads, from New York newspapers 6 ads, and 8 in Boston. Fried says, "Jensen’s results were corroborated in 2013 by Donald MacRaild."[26] Fried reports that historians who have endorsed Jensen's results include Tyler Anbinder,[27], Cathy Stanton,[28] Augusto Ferraiuolo,[29] and David A. Wilson.[30]. Fried says, “Jensen’s conclusions about these facts have coalesced into something like a ‘consensus’ view.”

20th century

A 2004 report by the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs stated that Irish soldiers in World War I were treated more harshly in courts-martial because British officers had "a racist bias against Irish soldiers".[31]

In 1934, J. B. Priestley published the travelogue English Journey, in which he wrote "A great many speeches have been made and books written on the subject of what England has done to Ireland... I should be interested to hear a speech and read a book or two on the subject of what Ireland has done to England... if we do have an Irish Republic as our neighbour, and it is found possible to return her exiled citizens, what a grand clearance there will be in all the western ports, from the Clyde to Cardiff, what a fine exit of ignorance and dirt and drunkenness and disease."[32]

Since the formation of Northern Ireland in 1921, there has been tension and violence between its two main communities. Most of the Irish nationalist/republican community are Catholic and see themselves as Irish, while most of the unionist/loyalist community are Protestant and see themselves as British. Since The Troubles began in the late 1960s, loyalists have consistently expressed anti-Irish sentiment. Irish tricolours, daubed with the loyalist slogan "Kill All Irish" (KAI), have been burnt on the yearly Eleventh Night bonfires.[33] In August 1993 the Red Hand Commando announced that it would attack pubs or hotels where Irish folk music is played, although it withdrew the threat shortly after.[34] In 2000, loyalists made posters and banners that read "The Ulster conflict is about nationality. IRISH OUT!".[35] Some of the Provisional IRA's bombings in England led to anti-Irish sentiment and attacks on the Irish community there. After the Birmingham pub bombings, for example, there were reports of isolated attacks on Irish people and Irish-owned businesses in the Australian press.[36] In the 1990s, writers for the Daily Mail newspaper "called for Irish people to be banned from UK sporting events and fined for IRA disruption to public transport", one of numerous opinions expressed over many years which has led the Daily Mail to be accused by some in Ireland of publishing "some of the most virulently anti-Irish journalism in Britain for decades".[37]

21st century

In 2002, English journalist Julie Burchill narrowly escaped prosecution for incitement to racial hatred, following a column in The Guardian where she described Ireland as being synonymous with "child molestation, Nazi-sympathising, and the oppression of women."[38] Burchill had expressed anti-Irish sentiment several times throughout her career, announcing in the London journal Time Out that "I hate the Irish, I think they're appalling".[39]

In 2012, The Irish Times carried a report on anti-Irish prejudice in Britain. It claimed that far-right British nationalist groups continued to use "anti-IRA" marches as "an excuse to attack and intimidate Irish immigrants".[40] Shortly before the 2012 Summer Olympics, British athlete Daly Thompson made an anti-Irish statement on live television. When Thompson was shown an image of a runner with a misspelt tattoo, he said that the person responsible for the misspelling must have been Irish. The BBC issued an apology.[41]

In March 2012 in Perth Australia, one classified ad placed by a bricklayer stated "No Irish Need Apply".[42]

On 8 August 2012, an article appeared in Australian newspapers titled "Punch Drunk: Ireland intoxicated as Taylor swings towards boxing gold". The article claimed that Katie Taylor was not "what you'd expect in a fighting Irishwoman, nor is she surrounded by people who'd prefer a punch to a potato". The journalist who wrote it apologised for "indulging racial stereotypes".[43] The following day, Australian commentator Russell Barwick asserted that athletes from Ireland should compete for the British Olympic team, likening it to "an Hawaiian surfer not surfing for the USA". When fellow presenter Mark Chapman explained that the Republic of Ireland was an independent state, Barwick remarked: "It's nothing but an Irish joke".[44][45]

On 25 June 2013, In an Orange Order HQ in Everton, Liverpool an Irish Flag was burned. Considering that Liverpool is a city with many second and third-generation Irish immigrants, this was seen by members of Liverpool's Irish community as a hate crime.[46]

In response to the relatively high numbers of Irish immigrants being murdered in Australia[citation needed], the parents of one victim, David Greene, who was attacked and killed in August 2012, have issued wallet sized cards to be given to any Irish people travelling to Australia, with a list of the names and contact details for people who need help in the form of legal assistance or advice if they are attacked.[47]

In December 2014 Channel 4 caused an "outrage" and "fury" in Ireland by announcing it planned a comedy series about the Irish Famine. The situation comedy, named Hungry, was announced by writer Hugh Travers, who said “we’re kind of thinking of it as Shameless in famine Ireland.” The response in Ireland was quick and negative: “Jewish people would never endorse making a comedy of the mass extermination of their ancestors at the hands of the Nazis, Cambodians would never support people laughing at what happened to their people at the hands of the Khmer Rouge and the people of Somalia, Ethiopia or Sudan would never accept the plight of their people, through generational famine, being the source of humour in Britain,” Dublin councillor David McGuinness said. “I am not surprised that it is a British television outlet funding this venture.” The writer defended the concept saying, "Comedy equals tragedy plus time."[48][49]It is reported that thousands of people have signed an on-line petition protesting the proposed series. The petition states: 'Famine or genocide is no laughing matter, approximately one million Irish people died and another two million were forced to emigrate because they were starving...Any programme on this issue would have to be of serious historical context... not a comedy.'[50] British broadcaster Channel 4 issued a press release responding to protests of the plan for the comedy series. “This in the development process and is not currently planned to air... It’s not unusual for sitcoms to exist against backdrops that are full of adversity and hardship,” it read. [51] Protesters planned to picket the offices of Channel 4 and campaigners are calling the show 'institutionalised anti-Irish racism'.[52]

Irish Traveller discrimination

Irish Travellers are an indigenous minority present for centuries in Ireland, who suffer overt discrimination throughout Ireland[53][54] and the United Kingdom.[55] Similar in nature to antiziganism (prejudice against Romani people)[56] in the United Kingdom and Europe.[55] Anti-Traveller racism is similar to that experienced by the Irish during the diaspora of the 19th century,[57] with media attack campaigns in the United Kingdom,[58] and in Ireland using both national/local newspapers and radio.[59][60][61] Irish Travellers in the Irish media have stated they are living in Ireland under an apartheid regime.[62] In 2013, Irish journalist Jennifer O'Connell writing in The Irish Times carried an article rasing the question 'Our casual racism against Travellers is one of Ireland's last great shames'.[63] While there is a willingness to acknowledge that there is widespread prejudice towards Travellers in Irish society, and a recognition of discrimination against Travellers, there is still strong resistance among the Irish public to calling the treatment of Travellers racist.[62] While discrimination may occur to Travellers in employment [64] and secondary school place allocation,[65] it is limited.

Extensive abuses of social systems like the housing scheme, welfare schemes, and resource teachers for Travellers in primary schools perpetuate the social conflict between Travellers and "the settled community" examples being burning down of houses allocated to the Travellers by the state due to Traveller feuds.[66] These feuds between large traveller families often culminate in mass brawls where dozens of travellers fight each other and cause damage to themselves as well as public and private property. In 2013 a Traveller home in Ballyshannon, Co Donegal was destroyed by fire days before members of a Traveller family were due to move in.[63] Local Councillor Pearse Doherty said the house was specifically targeted because it was to house a Traveller family and was destroyed due to a 'hatred of Travellers'.[67] Another local Councillor Sean McEniff of Bundoran caused controversy and a complaint under the 'Incitement to Hatred Act' when he stated due to the houses initial purchase that Travellers “should live in isolation from the settled community.” and "I would not like these people (the family) living beside me,”.[67]

The British television series Big Fat Gypsy Weddings has been accused of bullying and an instigation of racial hatred against Irish Travellers in England. The series has faced a number of controversies, including allegations of racism in its advertising[68][69] and instigating a rise in the rate of racially motivated bullying.[70]

See also

- Sectarianism in Glasgow

- Anti-Catholicism

- White ethnic

- Philadelphia Nativist Riots

- Stage Irish

- Black Irish

References

- ^ "Racism in Ireland – Travellers". Flag.blackened.net. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ Irish Travellers: Racism and the Politics of Culture – Jane Helleiner – Google Books. Books.google.co.jp. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ "British court rules Irish travellers covered by Race Relations laws – RTÉ News". Rte.ie. 29 August 2000. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ "History Ireland". History Ireland. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ Reformation in Ireland

- ^ http://castle.eiu.edu/historia/archives/2006/Henderson.pdf

- ^ Austin Lane Poole. From Domesday book to Magna Carta, 1087–1216. Oxford University Press 1993. pp. 303–304.

- ^ Hull, Eleanor. "POPE ADRIAN'S BULL "LAUDABILITER" AND NOTE UPON IT", from A History of Ireland and Her People (1931).

- ^ Gerald of Wales, Giraldus, John Joseph O'Meara. The History and Topography of Ireland. Penguin Classics, 1982. Page 102.

- ^ James West Davidson. Nation of Nations: A Concise Narrative of the American Republic. McGraw-Hill, 1996. Page 27.

- ^ Hastings, Adrian (1997). The Construction of Nationhood: Ethnicity, Religion and Nationalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59391-3, ISBN 0-521-62544-0. pp. 83–84.

- ^ Travels to terra incognita: the Scottish Highlands and Hebrides in early modern travellers accounts. c1600-1800. Martin Rackwitz. Waxmann Verlag 2007.p33, p94

- ^ The Irish in Atlantic Canada, 1780–1900

- ^ IRISH IMMIGRANTS AND CANADIAN DESTINIES IN MARGARET ATWOOD'S "ALIAS GRACE" Ecaterina Hanţiu University of Oradea.

- ^ "Kirk 'regret' over bigotry – BBC.co.uk". BBC News. 29 May 2002. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ Irish society: sociological perspectives By Patrick Clancy

- ^ "Voltaire's writing, particular in this field of history, show by this stage in his career Ireland and the Catholic Irish had become shorthand reference to extreme religious fanaticism and general degeneracy".Gargett, Graham: "Some Reflections on Voltaire's L'lngenu and a Hitherto Neglected Source: the Questions sur les miracles" in The Secular City: Studies in the Enlightenment : Presented to Haydn Mason edited by T. D. Hemming, Edward Freeman, David Meakin University of Exeter Press, 1994 ISBN 0859894169.

- ^ a b Wohl, Anthony S. (1990) "Racism and Anti-Irish Prejudice in Victorian England". The Victorian Web

- ^ Cahill, Thomas (1995). How the Irish Saved Civilization – The Untold Story of Ireland's Heroic Role from the Fall of Rome to the Rise of Medieval Europe. 1540 Broadway, New York, NY 10036: Doubleday. p. 6. ISBN 0-385-41849-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Hoeber, Francis W. (2001) "Drama in the Courtroom, Theater in the Streets: Philadelphia's Irish Riot of 1831" Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 125(3): 191–232. ISSN 0031-4587

- ^ Prince, Carl E. (1985) "The Great 'Riot Year': Jacksonian Democracy and Patterns of Violence in 1834." Journal of the Early Republic 5(1): 1–19. ISSN 0275-1275 examines 24 episodes including the January labor riot at the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, the New York City election riot in April, the Philadelphia race riot in August, and the Baltimore & Washington Railroad riot in November.

- ^ John G. West, Iain S. MacLean, Encyclopedia of religion in American politics, Volume 2, Greenwood Publishing Group (1999).

- ^ a b c d Jensen, Richard (2002, revised for web 2004) "'No Irish Need Apply': A Myth of Victimization". Journal of Social History issn.36.2 pp.405–429

- ^ http://www.longislandwins.com/columns/detail/high_school_student_proves_professor_wrong_when_he_denied_no_irish_need_app

- ^ Fried, Rebecca A. (2015) "No Irish Need Deny: Evidence for the Historicity of NINA Restrictions in Advertisements and Signs" Journal of Social History 48. Accessed 17 July 2015. doi: 10.1093/jsh/shv066.

In addition to job postings, the article also surveys evidence relevant to several of Jensen's subsidiary arguments, including lawsuits involving NINA publications, NINA restrictions in housing solicitations, Irish-American responses to NINA advertisements, and the use of NINA advertisements in Confederate propaganda", and concludes (per the abstract) that "Jensen's thesis about the highly limited extent of NINA postings requires revision", and that "the earlier view of historians generally accepting the widespread reality of the NINA phenomenon is better supported by the currently available evidence." - ^ Donald M. MacRaild, “‘No Irish Need Apply’: The Origins and Persistence of a Prejudice,” Labour History Review 78 (2013): 269-299)

- ^ Tyler Anbinder, “Nativism and Prejudice Against Immigrants,” in A Companion to American Immigration, ed. Reed Ueda (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2006), 188-89.

- ^ Cathy Stanton, The Lowell Experiment: Public History in a Post-Industrial City (University of Massachusetts Press, 2006), pp 79 and 268 n.8.

- ^ Augusto Ferraiuolo, Religious Festive Practices in Boston's North End: Ephemeral Identities in an Italian American Community (State University of New York Press, 2009), pp 238-39 n.21)

- ^ David A. Wilson, “Introduction,” in Wilson, ed., Irish Nationalism in Canada, (McGill-Queens University Press, 2009), p 5.

- ^ "UK military justice was 'anti-Irish': secret report". Irish Independent, 7 August 2005. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ J. B. Priestley, English Journey (London: William Heinemann, 1934), pp. 248-9

- ^ Bowcott, Owen (13 July 2006). "Army off streets for July 12". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Chronology of the Conflict: August 1993. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN).

- ^ "Loyalist Feud: 31 July – 2 September 2000". Pat Finucane Centre. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ "Every Briton now a target for death". Sydney Morning Herald. 1 December 1974.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Anti-Irish newspaper plans to launch edition here". Irish Independent, 25 September 2005. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ The Sunday Business Post, 25 August 2002, Unruly Julie: Julie Burchill

- ^ Lindsay Shapero, 'Red devil', Time Out, 17–23 Mary 1984, p. 27

- ^ Whelan, Brian (17 July 2012). "Return of anti-Irish prejudice in Britain?". The Irish Times. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ "Daley Thompson in race row over anti-Irish joke on BBC". Irish Independent. 2 December 2012.

- ^ "Australian bricklayer employment ad says "No Irish" need apply". IrishCentral.com. 13 March 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ "'Fighting Irish' article prompts apology". Irish Times.

- ^ "Aussie journalist 'sorry' for suggesting Ireland should join Team GB". thejournal.ie.

- ^ "ESPN's Aussie presenter's Irish Olympic rant". Irish Echo.

- ^ "Liverpool Confidential your guide to city life, eating out, night life, food and drink, bars, and more". Liverpool Confidential. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ "Luke James Wentholt jailed for murder of Irish backpacker David Greene in Melbourne". RTÉ News. 17 September 2013.

- ^ "Ian Burrell 'Potato famine comedy prompts Irish outrage at Channel 4'(2 Jan 2015) the Independent" http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/tv/news/potato-famine-comedy-prompts-irish-outrage-at-channel-4-9954913.html

- ^ "Jilly Beatty 'Fury as British TV station commissions family sitcom based on the Irish famine' (2 Jan 2015) The Irish Mirror" http://www.irishmirror.ie/whats-on/arts-culture-news/fury-british-tv-station-commissions-4910380

- ^ "Jack Crone 'Is this the most tasteless idea for a sitcom ever? Channel 4 commissions 'new Shameless' to be set during the Irish POTATO FAMINE' (3 Jan 2015) The Daily Mail" http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2895252/Is-tasteless-idea-sitcom-Channel-4-commissions-new-Shameless-set-Irish-POTATO-FAMINE.html

- ^ Famine historian Tim Pat Coogan criticizes Channel 4 sitcom Irish Central 5 Jan 2015

- ^ Demo planned over famine comedy: Protesters to descend on Channel 4 Chortle, 8 Jan 2015

- ^ "On the Road to Recognition: Irish Travellers' quest for Ethnic Identity (Saint Louis University of Law)" (PDF). Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- ^ The political geography of anti-Traveller racism in Ireland: the politics of exclusion and the geography of closure. Jim MacLaughlin Department of Geography, University College, Cork, Ireland

- ^ a b Jane Helleiner (1 May 2003). Irish Travellers: Racism and the Politics of Culture. University of Toronto Press. pp. 29–. ISBN 978-0-8020-8628-0. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ "Was ist EZAF ? | Europäisches Zentrum für Antiziganismusforschung und -bekämpfung". Ezaf.org. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ Racial,ethnic, and homophobic violence: killing in the name of otherness (p18) Marie-Claude Barbier, Bénédicte Deschamps, Michel Prum Routledge-Cavendish, 2007

- ^ Jaya Narain (11 March 2010). "Anger as judge awards 'illegal' travellers' camp its own postcode... despite opposition from local council and residents | Mail Online". London: Dailymail.co.uk. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ "They are dirty and unclean. Travelling people have no respect for themselves and their children". (County Councillor quoted in Irish Times, 13 March 1991) cited in http://www.paveepoint.ie/pav_irerac_3.html

- ^ "Killarney is literally infested by these people." (County Councillor quoted in Cork Examiner, 18 July 1989) cited in http://www.paveepoint.ie/pav_irerac_3.html

- ^ "Deasy suggests birth control to limit traveller numbers" (Headline in Irish Times, Friday, 15 June 1996.) cited in http://www.paveepoint.ie/pav_irerac_3.html

- ^ a b Buckley, Dan (15 December 2006). "Racist attitudes towards Travellers must be dealt with urgently | Irish Examiner". Examiner.ie. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ a b "Our casual racism against Travellers is one of Ireland's last great shames". Irish Times. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ Pavee Point – Unless otherwise noted. "Pavee Point Factsheets – Travellers and Work". Paveepoint.ie. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ Email Us (5 July 2011). "School appeals entry bias against Traveller – The Irish Times – Tue, Jul 05, 2011". The Irish Times. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ http://www.waterfordcity.ie/documents/reports/TAP2009-2013.doc

- ^ a b http://donegalnews.com/2013/02/controversial-ballyshannon-house-burned-down/

- ^ "Big Fat Gypsy Wedding sponsors forced to apologise for 'racist' advert". The Mirror. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ^ Sweney, Mark (3 October 2012). "Big Fat Gypsy Weddings012/oct/03/big-fat-gypsy-weddings-stereotypes". London: The Guardian.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Plunkett, John (16 October 2012). "Big Fat Gypsy Weddings 'has increased bullying of Gypsies and Travellers'". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 12 November 2012.