Common cold: Difference between revisions

15-30% |

|||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

<!-- Symptoms and cause --> |

<!-- Symptoms and cause --> |

||

The '''common cold''' (also known as '''nasopharyngitis''', '''rhinopharyngitis''', '''acute coryza''', '''head cold''', or simply '''a cold''') is a viral [[infectious disease]] of the [[upper respiratory tract]] which primarily affects the nose. Symptoms include [[cough]]ing, [[sore throat]], [[rhinorrhea|runny nose]], [[Sneeze|sneezing]], and [[fever]] which usually resolve in seven to ten days, with some symptoms lasting up to three weeks. Over 200 viruses are implicated in the cause of the common cold; the [[rhinovirus]]es and two coronaviruses are the most common. [[Human coronavirus OC43]] and [[Human coronavirus 229E]] cause |

The '''common cold''' (also known as '''nasopharyngitis''', '''rhinopharyngitis''', '''acute coryza''', '''head cold''', or simply '''a cold''') is a viral [[infectious disease]] of the [[upper respiratory tract]] which primarily affects the nose. Symptoms include [[cough]]ing, [[sore throat]], [[rhinorrhea|runny nose]], [[Sneeze|sneezing]], and [[fever]] which usually resolve in seven to ten days, with some symptoms lasting up to three weeks. Over 200 viruses are implicated in the cause of the common cold; the [[rhinovirus]]es and two coronaviruses are the most common. [[Human coronavirus OC43]] and [[Human coronavirus 229E]] cause 15-30% of common colds. |

||

<!-- Prevention, diagnosis and pathophysiology --> |

<!-- Prevention, diagnosis and pathophysiology --> |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

===Virology=== |

===Virology=== |

||

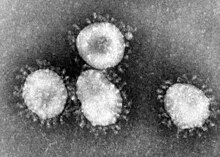

[[File:Coronaviruses 004 lores.jpg|thumb|[[Coronavirus]]es are a group of viruses known for causing the common cold. They have a halo, or crown-like (corona) appearance when viewed under an electron microscope.]] |

[[File:Coronaviruses 004 lores.jpg|thumb|[[Coronavirus]]es are a group of viruses known for causing the common cold. They have a halo, or crown-like (corona) appearance when viewed under an electron microscope.]] |

||

The common cold is a viral infection of the upper respiratory tract. The most commonly implicated virus is a [[rhinovirus]] (30–80%), a type of [[picornavirus]] with 99 known [[serovar|serotypes]].<ref>{{cite journal | author = Palmenberg AC, Spiro D, Kuzmickas R, Wang S, Djikeng A, Rathe JA, Fraser-Liggett CM, Liggett SB | title = Sequencing and Analyses of All Known Human Rhinovirus Genomes Reveals Structure and Evolution | journal = Science | volume = 324 | issue = 5923 | pages = 55–9 | year = 2009 | pmid = 19213880 | doi = 10.1126/science.1165557 }}</ref><ref>Eccles Pg.77</ref> Others include: [[coronavirus]] (30%),<ref>Mariana Mesel-Lemoine, Jean Millet, Pierre-Olivier Vidalain, et al. A Human Coronavirus Responsible for the Common Cold Massively Kills Dendritic Cells but Not Monocytes. J. Virol. July 2012 vol. 86 no. 14 7577-7587</ref> [[Orthomyxoviridae|influenza viruses]] (10-15%),<ref name=Medscape>{{cite web|title=Rhinovirus Infection|url=http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/227820-overview#a0101|publisher=Medscape Reference|accessdate=19 March 2013|author=Michael Rajnik|coauthors=Robert W Tolan|date=13|month=Sep|year=2013}}</ref> [[Adenoviridae|adenoviruses]] (5%),<ref name=Medscape/> [[human parainfluenza viruses]], [[human respiratory syncytial virus]], [[enterovirus]]es other than rhinoviruses, and [[metapneumovirus]].<ref name="NIAID2006">{{cite web | title = Common Cold | publisher = [[National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases]] | date = 27 November 2006 | url = http://www3.niaid.nih.gov/healthscience/healthtopics/colds/ | accessdate = 11 June 2007}}</ref> Frequently more than one virus is present.<ref>Eccles Pg.107</ref> In total over 200 different viral types are associated with colds.<ref name=Eccles2005/> |

The common cold is a viral infection of the upper respiratory tract. The most commonly implicated virus is a [[rhinovirus]] (30–80%), a type of [[picornavirus]] with 99 known [[serovar|serotypes]].<ref>{{cite journal | author = Palmenberg AC, Spiro D, Kuzmickas R, Wang S, Djikeng A, Rathe JA, Fraser-Liggett CM, Liggett SB | title = Sequencing and Analyses of All Known Human Rhinovirus Genomes Reveals Structure and Evolution | journal = Science | volume = 324 | issue = 5923 | pages = 55–9 | year = 2009 | pmid = 19213880 | doi = 10.1126/science.1165557 }}</ref><ref>Eccles Pg.77</ref> Others include: [[coronavirus]] (15-30%),<ref>Mariana Mesel-Lemoine, Jean Millet, Pierre-Olivier Vidalain, et al. A Human Coronavirus Responsible for the Common Cold Massively Kills Dendritic Cells but Not Monocytes. J. Virol. July 2012 vol. 86 no. 14 7577-7587</ref> [[Orthomyxoviridae|influenza viruses]] (10-15%),<ref name=Medscape>{{cite web|title=Rhinovirus Infection|url=http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/227820-overview#a0101|publisher=Medscape Reference|accessdate=19 March 2013|author=Michael Rajnik|coauthors=Robert W Tolan|date=13|month=Sep|year=2013}}</ref> [[Adenoviridae|adenoviruses]] (5%),<ref name=Medscape/> [[human parainfluenza viruses]], [[human respiratory syncytial virus]], [[enterovirus]]es other than rhinoviruses, and [[metapneumovirus]].<ref name="NIAID2006">{{cite web | title = Common Cold | publisher = [[National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases]] | date = 27 November 2006 | url = http://www3.niaid.nih.gov/healthscience/healthtopics/colds/ | accessdate = 11 June 2007}}</ref> Frequently more than one virus is present.<ref>Eccles Pg.107</ref> In total over 200 different viral types are associated with colds.<ref name=Eccles2005/> |

||

===Transmission=== |

===Transmission=== |

||

Revision as of 11:12, 10 November 2013

| Common cold | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Family medicine, infectious diseases, otorhinolaryngology |

The common cold (also known as nasopharyngitis, rhinopharyngitis, acute coryza, head cold, or simply a cold) is a viral infectious disease of the upper respiratory tract which primarily affects the nose. Symptoms include coughing, sore throat, runny nose, sneezing, and fever which usually resolve in seven to ten days, with some symptoms lasting up to three weeks. Over 200 viruses are implicated in the cause of the common cold; the rhinoviruses and two coronaviruses are the most common. Human coronavirus OC43 and Human coronavirus 229E cause 15-30% of common colds.

Upper respiratory tract infections are loosely divided by the areas they affect, with the common cold primarily affecting the nose, the throat (pharyngitis), and the sinuses (sinusitis), occasionally involving either or both eyes via conjunctivitis. Symptoms are mostly due to the body's immune response to the infection rather than to tissue destruction by the viruses themselves. The primary method of prevention is by hand washing with some evidence to support the effectiveness of wearing face masks. The common cold may occasionally lead to pneumonia, either viral pneumonia or secondary bacterial pneumonia.

No cure for the common cold exists, but the symptoms can be treated. It is the most frequent infectious disease in humans with the average adult contracting two to three colds a year and the average child contracting between six and twelve. These infections have been with humanity since antiquity.

Signs and symptoms

The typical symptoms of a cold include cough, runny nose, nasal congestion and a sore throat, sometimes accompanied by muscle ache, fatigue, headache, and loss of appetite.[1] A sore throat is present in about 40% of the cases and a cough in about 50%,[2] while muscle ache occurs in about half.[3] In adults, a fever is generally not present but it is common in infants and young children.[3] The cough is usually mild compared to that accompanying influenza.[3] While a cough and a fever indicate a higher likelihood of influenza in adults, a great deal of similarity exists between these two conditions.[4] A number of the viruses that cause the common cold may also result in asymptomatic infections.[5][6] The color of the sputum or nasal secretion may vary from clear to yellow to green and does not indicate the class of agent causing the infection.[7]

Progression

A cold usually begins with fatigue, a feeling of being chilled, sneezing and a headache, followed in a couple of days by a runny nose and cough.[1] Symptoms may begin within 16 hours of exposure[8] and typically peak two to four days after onset.[3][9] They usually resolve in seven to ten days but some can last for up to three weeks.[10] The average duration of cough is 18 days[11] and in some cases people develop a post-viral cough which can linger after the infection is gone.[12] In children, the cough lasts for more than ten days in 35–40% of the cases and continues for more than 25 days in 10%.[13]

Cause

Virology

The common cold is a viral infection of the upper respiratory tract. The most commonly implicated virus is a rhinovirus (30–80%), a type of picornavirus with 99 known serotypes.[14][15] Others include: coronavirus (15-30%),[16] influenza viruses (10-15%),[17] adenoviruses (5%),[17] human parainfluenza viruses, human respiratory syncytial virus, enteroviruses other than rhinoviruses, and metapneumovirus.[18] Frequently more than one virus is present.[19] In total over 200 different viral types are associated with colds.[3]

Transmission

The common cold virus is typically transmitted via airborne droplets (aerosols), direct contact with infected nasal secretions, or fomites (contaminated objects).[2][20] Which of these routes is of primary importance has not been determined; however, hand-to-hand and hand-to-surface-to-hand contact seems of more importance than transmission via aerosols.[21] The viruses may survive for prolonged periods in the environment (over 18 hours for rhinoviruses) and can be picked up by people's hands and subsequently carried to their eyes or nose where infection occurs.[20] Transmission is common in daycare and at school due to the proximity of many children with little immunity and frequently poor hygiene.[22] These infections are then brought home to other members of the family.[22] There is no evidence that recirculated air during commercial flight is a method of transmission.[20] However, people sitting in proximity appear at greater risk.[21] Rhinovirus-caused colds are most infectious during the first three days of symptoms; they are much less infectious afterwards.[23]

Weather

The traditional folk theory is that a cold can be "caught" by prolonged exposure to cold weather such as rain or winter conditions, which is how the disease got its name.[24] Some of the viruses that cause the common colds are seasonal, occurring more frequently during cold or wet weather.[25] The reason for the seasonality has not been conclusively determined.[26] This may occur due to cold induced changes in the respiratory system,[27] decreased immune response,[28] and low humidity increasing viral transmission rates, perhaps due to dry air allowing small viral droplets to disperse farther and stay in the air longer.[29] It may be due to social factors, such as people spending more time indoors, near an infected person,[27] and specifically children at school.[22][26] There is some controversy over the role of body cooling as a risk factor for the common cold; the majority of the evidence suggests that it may result in greater susceptibility to infection.[28]

Other

Herd immunity, generated from previous exposure to cold viruses, plays an important role in limiting viral spread, as seen with younger populations that have greater rates of respiratory infections.[30] Poor immune function is also a risk factor for disease.[30][31] Insufficient sleep and malnutrition have been associated with a greater risk of developing infection following rhinovirus exposure; this is believed to be due to their effects on immune function.[32][33] Breast feeding decreases the risk of acute otitis media and lower respiratory tract infections among other diseases[34] and it is recommended that breast feeding be continued when an infant has a cold.[35] In the developed world breast feeding may not however be protective against the common cold in and of itself.[36]

Pathophysiology

The symptoms of the common cold are believed to be primarily related to the immune response to the virus.[37] The mechanism of this immune response is virus specific. For example, the rhinovirus is typically acquired by direct contact; it binds to human ICAM-1 receptors through unknown mechanisms to trigger the release of inflammatory mediators.[37] These inflammatory mediators then produce the symptoms.[37] It does not generally cause damage to the nasal epithelium.[3] The respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) on the other hand is contracted by both direct contact and airborne droplets. It then replicates in the nose and throat before frequently spreading to the lower respiratory tract.[38] RSV does cause epithelium damage.[38] Human parainfluenza virus typically results in inflammation of the nose, throat, and bronchi.[39] In young children when it affects the trachea it may produce the symptoms of croup due to the small size of their airway.[39]

Diagnosis

The distinction between different viral upper respiratory tract infections is loosely based on the location of symptoms with the common cold affecting primarily the nose, pharyngitis the throat, and bronchitis the lungs.[2] However there can be significant overlap and multiple areas can be affected.[2] The common cold is frequently defined as nasal inflammation with varying amount of throat inflammation.[40] Self-diagnosis is frequent.[3] Isolation of the actual viral agent involved is rarely performed,[40] and it is generally not possible to identify the virus type through symptoms.[3]

Prevention

The only possibly useful ways to reduce the spread of cold viruses are physical measures[41] such as hand washing and face masks; in the healthcare environment, gowns and disposable gloves are also used.[41] Isolation, e.g. quarantine, is not possible as the disease is so widespread and symptoms are non-specific. Vaccination has proved difficult as there are so many viruses involved and they mutate rapidly.[41] Creation of a broadly effective vaccine is thus highly improbable.[42]

Regular hand washing appears to be effective in reducing the transmission of cold viruses, especially among children.[43] Whether the addition of antivirals or antibacterials to normal hand washing provides greater benefit is unknown.[43] Wearing face masks when around people who are infected may be beneficial; however, there is insufficient evidence for maintaining a greater social distance.[43] Zinc supplements may help to reduce the prevalence of colds.[44] Routine vitamin C supplements do not reduce the risk or severity of the common cold, though they may reduce its duration.[45]

Management

No medications or herbal remedies have been conclusively demonstrated to shorten the duration of infection.[46] Treatment thus comprises symptomatic relief.[47] Getting plenty of rest, drinking fluids to maintain hydration, and gargling with warm salt water, are reasonable conservative measures.[18] Much of the benefit from treatment is however attributed to the placebo effect.[48]

Symptomatic

Treatments that help alleviate symptoms include simple analgesics and antipyretics such as ibuprofen[49] and acetaminophen/paracetamol.[50] Evidence does not show that cough medicines are any more effective than simple analgesics[51] and they are not recommended for use in children due to a lack of evidence supporting effectiveness and the potential for harm.[52][53] In 2009, Canada restricted the use of over-the-counter cough and cold medication in children six years and under due to concerns regarding risks and unproven benefits.[52] In adults there is insufficient evidence to support the use of cough medications.[54] The misuse of dextromethorphan (an over-the-counter cough medicine) has led to its ban in a number of countries.[55]

In adults the symptoms of a runny nose can be reduced by first-generation antihistamines; however, these sometimes have adverse effects such as drowsiness.[47] Other decongestants such as pseudoephedrine are also effective in adults.[56] Ipratropium nasal spray may reduce the symptoms of a runny nose but has little effect on stuffiness.[57] Second-generation antihistamines however do not appear to be effective.[58]

Due to lack of studies, it is not known whether increased fluid intake improves symptoms or shortens respiratory illness[59] and a similar lack of data exists for the use of heated humidified air.[60] One study has found chest vapor rub to provide some relief of nocturnal cough, congestion, and sleep difficulty.[61]

Antibiotics and antivirals

Antibiotics have no effect against viral infections and thus have no effect against the viruses that cause the common cold.[62] Due to their side effects antibiotics cause overall harm, but are still frequently prescribed.[62][63] Some of the reasons that antibiotics are so commonly prescribed include people's expectations for them, physicians' desire to help, and the difficulty in excluding complications that may be amenable to antibiotics.[64] There are no effective antiviral drugs for the common cold even though some preliminary research has shown benefits.[47][65]

Alternative medicine

While there are many alternative treatments used for the common cold, there is insufficient scientific evidence to support the use of most.[47] As of 2010 there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against either honey or nasal irrigation.[66][67] Zinc has been used to treat symptoms, with studies suggesting that zinc, if taken within 24 hours of the onset of symptoms, reduces the duration and severity of the common cold in otherwise healthy people.[44] Due to wide differences between the studies, further research may be needed to determine how and when zinc may be effective.[68] Whereas the zinc lozenges may produce side effects, there is only a weak rationale for physicians to recommend zinc for the treatment of the common cold.[69] Vitamin C's effect on the common cold, while extensively researched, is disappointing, except in limited circumstances, specifically, individuals exercising vigorously in cold environments.[45][70] Evidence about the usefulness of echinacea is inconsistent.[71][72] Different types of echinacea supplements may vary in their effectiveness.[71] It is unknown if garlic is effective.[73] A single trial of vitamin D did not find benefit.[74]

Prognosis

The common cold is generally mild and self-limiting with most symptoms generally improving in a week.[2] Severe complications, if they occur, are usually in the very old, the very young, or those who are immunosuppressed.[75] Secondary bacterial infections may occur resulting in sinusitis, pharyngitis, or an ear infection.[76] It is estimated that sinusitis occurs in 8% and an ear infection in 30% of cases.[77]

Epidemiology

The common cold is the most common human disease[75] and all peoples globally are affected.[22] Adults typically have two to five infections annually[2][3] and children may have six to ten colds a year (and up to twelve colds a year for school children).[47] Rates of symptomatic infections increase in the elderly due to a worsening immune system.[30]

Native Americans and Eskimos are more likely to be infected with colds and develop complications such as otitis media than Caucasians.[17] This may be explained by issues such as poverty and overcrowding rather than by ethnicity.[17]

History

While the cause of the common cold has only been identified since the 1950s the disease has been with humanity since antiquity.[78] Its symptoms and treatment are described in the Egyptian Ebers papyrus, the oldest existing medical text, written before the 16th century BCE.[79] The name "cold" came into use in the 16th century, due to the similarity between its symptoms and those of exposure to cold weather.[80]

In the United Kingdom, the Common Cold Unit was set up by the Medical Research Council in 1946 and it was here that the rhinovirus was discovered in 1956.[81] In the 1970s, the CCU demonstrated that treatment with interferon during the incubation phase of rhinovirus infection protects somewhat against the disease,[82] but no practical treatment could be developed. The unit was closed in 1989, two years after it completed research of zinc gluconate lozenges in the prophylaxis and treatment of rhinovirus colds, the only successful treatment in the history of the unit.[83]

Society and culture

The economic impact of the common cold is not well understood in much of the world.[77] In the United States, the common cold leads to 75–100 million physician visits annually at a conservative cost estimate of $7.7 billion per year. Americans spend $2.9 billion on over-the-counter drugs and another $400 million on prescription medicines for symptomatic relief.[85] More than one-third of people who saw a doctor received an antibiotic prescription, which has implications for antibiotic resistance.[85] An estimated 22–189 million school days are missed annually due to a cold. As a result, parents missed 126 million workdays to stay home to care for their children. When added to the 150 million workdays missed by employees suffering from a cold, the total economic impact of cold-related work loss exceeds $20 billion per year.[18][85] This accounts for 40% of time lost from work in the United States.[86]

Research directions

A number of antivirals have been tested for effectiveness in the common cold; however as of 2009 none have been both found effective and licensed for use.[65] There are ongoing trials of the anti-viral drug pleconaril which shows promise against picornaviruses as well as trials of BTA-798.[87] The oral form of pleconaril had safety issues and an aerosol form is being studied.[87]

DRACO, a broad-spectrum antiviral therapy being developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, has shown preliminary effectiveness in treating rhinovirus, as well as a number of other infectious viruses.[88][89]

Researchers from the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore and the University of Wisconsin–Madison have sequenced the genome for all known human rhinovirus strains.[90]

References

- ^ a b Eccles Pg. 24

- ^ a b c d e f Arroll B (2011). "Common cold". Clinical evidence. 2011 (3): 1510. PMC 3275147. PMID 21406124.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Eccles R (2005). "Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza". Lancet Infect Dis. 5 (11): 718–25. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70270-X. PMID 16253889.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Eccles Pg.26

- ^ Eccles Pg. 129

- ^ Eccles Pg.50

- ^ Eccles Pg.30

- ^ Textbook of therapeutics : drug and disease management (8. ed.). Philadelphia, Pa. [u.a.]: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2006. p. 1882. ISBN 9780781757348.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help);|first=missing|last=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ al.], edited by Helga Rübsamen-Waigmann ... [et (2003). Viral Infections and Treatment. Hoboken: Informa Healthcare. p. 111. ISBN 9780824756413.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Heikkinen T, Järvinen A (2003). "The common cold". Lancet. 361 (9351): 51–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12162-9. PMID 12517470.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ebell, MH (2013 Jan-Feb). "How long does a cough last? Comparing patients' expectations with data from a systematic review of the literature". Annals of Family Medicine. 11 (1): 5–13. doi:10.1370/afm.1430. PMC 3596033. PMID 23319500.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Dicpinigaitis PV (2011). "Cough: an unmet clinical need". Br. J. Pharmacol. 163 (1): 116–24. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01198.x. PMC 3085873. PMID 21198555.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Goldsobel AB, Chipps BE (2010). "Cough in the pediatric population". J. Pediatr. 156 (3): 352–358.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.12.004. PMID 20176183.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Palmenberg AC, Spiro D, Kuzmickas R, Wang S, Djikeng A, Rathe JA, Fraser-Liggett CM, Liggett SB (2009). "Sequencing and Analyses of All Known Human Rhinovirus Genomes Reveals Structure and Evolution". Science. 324 (5923): 55–9. doi:10.1126/science.1165557. PMID 19213880.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Eccles Pg.77

- ^ Mariana Mesel-Lemoine, Jean Millet, Pierre-Olivier Vidalain, et al. A Human Coronavirus Responsible for the Common Cold Massively Kills Dendritic Cells but Not Monocytes. J. Virol. July 2012 vol. 86 no. 14 7577-7587

- ^ a b c d Michael Rajnik (13). "Rhinovirus Infection". Medscape Reference. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c "Common Cold". National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. 27 November 2006. Retrieved 11 June 2007.

- ^ Eccles Pg.107

- ^ a b c editors, Ronald Eccles, Olaf Weber, (2009). Common cold (Online-Ausg. ed.). Basel: Birkhäuser. p. 197. ISBN 978-3-7643-9894-1.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Eccles Pp. 211 & 215

- ^ a b c d al.], edited by Arie J. Zuckerman ... [et (2007). Principles and practice of clinical virology (6th ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. p. 496. ISBN 978-0-470-51799-4.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Gwaltney JM Jr; Halstead SB.

{{cite journal}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) Invited letter in "Questions and answers". Journal of the American Medical Association. 278 (3): 256–257. 16 July 1997. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03550030096050. Retrieved 16 September 2011. - ^ Zuger, Abigail (4 March 2003). "'You'll Catch Your Death!' An Old Wives' Tale? Well." The New York Times.

- ^ Eccles Pg.79

- ^ a b "Common cold - Background information". National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ a b Eccles Pg.80

- ^ a b Mourtzoukou EG, Falagas ME (2007). "Exposure to cold and respiratory tract infections". The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 11 (9): 938–43. PMID 17705968.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Eccles Pg. 157

- ^ a b c Eccles Pg. 78

- ^ Eccles Pg.166

- ^ Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Alper CM, Janicki-Deverts D, Turner RB (2009). "Sleep habits and susceptibility to the common cold". Arch. Intern. Med. 169 (1): 62–7. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2008.505. PMC 2629403. PMID 19139325.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Eccles Pg.160–165

- ^ McNiel, ME (2010 Jul). "What are the risks associated with formula feeding? A re-analysis and review". Breastfeeding review : professional publication of the Nursing Mothers' Association of Australia. 18 (2): 25–32. PMID 20879657.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lawrence, Ruth A. Lawrence, Robert M. (30 September 2010). Breastfeeding a guide for the medical profession (7th ed.). Maryland Heights, Mo.: Mosby/Elsevier. p. 478. ISBN 9781437735901.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Williams, [edited by] Kenrad E. Nelson, Carolyn F. Masters (2007). Infectious disease epidemiology : theory and practice (2nd ed. ed.). Sudbury, Mass.: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. p. 724. ISBN 9780763728793.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Eccles Pg. 112

- ^ a b Eccles Pg.116

- ^ a b Eccles Pg.122

- ^ a b Eccles Pg. 51–52

- ^ a b c Eccles Pg.209

- ^ Lawrence DM (2009). "Gene studies shed light on rhinovirus diversity". Lancet Infect Dis. 9 (5): 278. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70123-9.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Jefferson T, Del Mar CB, Dooley L, Ferroni E, Al-Ansary LA, Bawazeer GA, van Driel ML, Nair S, Jones MA, Thorning S, Conly JM (2011). Jefferson, Tom (ed.). "Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD006207. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006207.pub4. PMID 21735402.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Singh M, Das RR (2011). Singh, Meenu (ed.). "Zinc for the common cold". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD001364. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001364.pub3. PMID 21328251.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Hemilä H, Chalker E, Douglas B, Hemilä H (2007). Hemilä, Harri (ed.). "Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD000980. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000980.pub3. PMID 17636648.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Common Cold: Treatments and Drugs". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 9 January 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Simasek M, Blandino DA (2007). "Treatment of the common cold". American Family Physician. 75 (4): 515–20. PMID 17323712.

- ^ Eccles Pg.261

- ^ Kim SY, Chang YJ, Cho HM, Hwang YW, Moon YS (2009). Kim, Soo Young (ed.). "Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the common cold". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD006362. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006362.pub2. PMID 19588387.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Eccles R (2006). "Efficacy and safety of over-the-counter analgesics in the treatment of common cold and flu". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 31 (4): 309–319. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.2006.00754.x. PMID 16882099.

- ^ Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T (2008). Smith, Susan M (ed.). "Over-the-counter (OTC) medications for acute cough in children and adults in ambulatory settings". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD001831. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001831.pub3. PMID 18253996.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Shefrin AE, Goldman RD (2009). "Use of over-the-counter cough and cold medications in children" (PDF). Can Fam Physician. 55 (11): 1081–3. PMC 2776795. PMID 19910592.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Vassilev ZP, Kabadi S, Villa R (2010). "Safety and efficacy of over-the-counter cough and cold medicines for use in children". Expert opinion on drug safety. 9 (2): 233–42. doi:10.1517/14740330903496410. PMID 20001764.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smith, SM (2012 Aug 15). Smith, Susan M (ed.). "Over-the-counter (OTC) medications for acute cough in children and adults in ambulatory settings". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online). 8: CD001831. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001831.pub4. PMID 22895922.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Eccles Pg. 246

- ^ Taverner D, Latte GJ (2007). Latte, G. Jenny (ed.). "Nasal decongestants for the common cold". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD001953. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001953.pub3. PMID 17253470.

- ^ Albalawi ZH, Othman SS, Alfaleh K (2011). Albalawi, Zaina H (ed.). "Intranasal ipratropium bromide for the common cold". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD008231. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008231.pub2. PMID 21735425.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pratter MR (2006). "Cough and the common cold: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines". Chest. 129 (1 Suppl): 72S–74S. doi:10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.72S. PMID 16428695.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Guppy MP, Mickan SM, Del Mar CB, Thorning S, Rack A (2011). Guppy, Michelle PB (ed.). "Advising patients to increase fluid intake for treating acute respiratory infections". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD004419. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004419.pub3. PMID 21328268.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Singh M, Singh M (2011). Singh, Meenu (ed.). "Heated, humidified air for the common cold". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD001728. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001728.pub4. PMID 21563130.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Paul IM, Beiler JS, King TS, Clapp ER, Vallati J, Berlin CM (2010). "Vapor rub, petrolatum, and no treatment for children with nocturnal cough and cold symptoms". Pediatrics. 126 (6): 1092–9. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1601. PMC 3600823. PMID 21059712.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Arroll B, Kenealy T (2005). Arroll, Bruce (ed.). "Antibiotics for the common cold and acute purulent rhinitis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD000247. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000247.pub2. PMID 16034850.

- ^ Eccles Pg.238

- ^ Eccles Pg.234

- ^ a b Eccles Pg.218

- ^ Oduwole O, Meremikwu MM, Oyo-Ita A, Udoh EE (2010). Oduwole, Olabisi (ed.). "Honey for acute cough in children". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD007094. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007094.pub2. PMID 20091616.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kassel JC, King D, Spurling GK (2010). King, David (ed.). "Saline nasal irrigation for acute upper respiratory tract infections". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD006821. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006821.pub2. PMID 20238351.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Zinc for the common cold — Health News — NHS Choices". nhs.uk. 2012 [last update]. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

In this review, there was a high level of heterogeneity between the studies that were pooled to determine the effect of zinc on the duration of cold symptoms. This may suggest that it was inappropriate to pool them. It certainly makes this particular finding less conclusive.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Science, M. (7 May 2012). "Zinc for the treatment of the common cold: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 184 (10): E551–E561. doi:10.1503/cmaj.111990. PMC 3394849. PMID 22566526.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Heiner KA, Hart AM, Martin LG, Rubio-Wallace S (2009). "Examining the evidence for the use of vitamin C in the prophylaxis and treatment of the common cold". Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 21 (5): 295–300. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2009.00409.x. PMID 19432914.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Linde K, Barrett B, Wölkart K, Bauer R, Melchart D (2006). Linde, Klaus (ed.). "Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD000530. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000530.pub2. PMID 16437427.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sachin A Shah, Stephen Sander, C Michael White, Mike Rinaldi, Craig I Coleman (2007). "Evaluation of echinacea for the prevention and treatment of the common cold: a meta-analysis". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 7 (7): 473–480. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70160-3. PMID 17597571.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lissiman E, Bhasale AL, Cohen M (2012). Lissiman, Elizabeth (ed.). "Garlic for the common cold". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3: CD006206. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006206.pub3. PMID 22419312.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Murdoch, David R. (3 October 2012). "Effect of Vitamin D3 Supplementation on Upper Respiratory Tract Infections in Healthy Adults<subtitle>The VIDARIS Randomized Controlled Trial</subtitle><alt-title>Vitamin D3 and Upper Respiratory Tract Infections</alt-title>". JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 308 (13): 1333. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.12505.

- ^ a b Eccles Pg. 1

- ^ Eccles Pg.76

- ^ a b Eccles Pg.90

- ^ Eccles Pg. 3

- ^ Eccles Pg.6

- ^ "Cold". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 12 January 2008.

- ^ Eccles Pg.20

- ^ Tyrrell DA (1987). "Interferons and their clinical value". Rev. Infect. Dis. 9 (2): 243–9. doi:10.1093/clinids/9.2.243. PMID 2438740.

- ^ Al-Nakib W; Higgins, P.G.; Barrow, I.; Batstone, G.; Tyrrell, D.A.J. (1987). "Prophylaxis and treatment of rhinovirus colds with zinc gluconate lozenges". J Antimicrob Chemother. 20 (6): 893–901. doi:10.1093/jac/20.6.893. PMID 3440773.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "The Cost of the Common Cold and Influenza". Imperial War Museum: Posters of Conflict. vads.

- ^ a b c Fendrick AM, Monto AS, Nightengale B, Sarnes M (2003). "The economic burden of non-influenza-related viral respiratory tract infection in the United States". Arch. Intern. Med. 163 (4): 487–94. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.4.487. PMID 12588210.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kirkpatrick GL (1996). "The common cold". Prim. Care. 23 (4): 657–75. doi:10.1016/S0095-4543(05)70355-9. PMID 8890137.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Eccles Pg.226

- ^ Rider TH, Zook CE, Boettcher TL, Wick ST, Pancoast JS, Zusman BD (2011). Sambhara, Suryaprakash (ed.). "Broad-spectrum antiviral therapeutics". PLoS ONE. 6 (7): e22572. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022572. PMC 3144912. PMID 21818340.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Fiona Macrae (11 August 2011). "Greatest discovery since penicillin: A cure for everything - from colds to HIV". The Daily Mail. UKTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Val Willingham (12 February 2009). "Genetic map of cold virus a step toward cure, scientists say". CNN. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

Further reading

- Ronald Eccles, Olaf Weber (eds) (2009). Common cold. Basel: Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-3-7643-9894-1.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)