Vilnius University: Difference between revisions

PLease use talk page before starting edit war. Your edit does not comply with WP:NCGN |

|||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Vilnius University''' ({{lang-lt|Vilniaus universitetas |

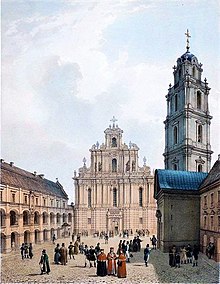

'''Vilnius University''' ({{lang-lt|Vilniaus universitetas}}) is the [[List of oldest universities in continuous operation|oldest university]] in the [[Baltic states]] and one of the oldest in [[Eastern Europe]]. It is also the largest [[university]] in [[List of universities in Lithuania|Lithuania]]. |

||

==Names== |

==Names== |

||

Revision as of 22:16, 5 March 2011

Vilniaus Universitetas | |

| |

| Latin: Universitas Vilnensis | |

| Type | Public |

|---|---|

| Established | 1579 |

| Chancellor | Benediktas Juodka |

Academic staff | 1 517 [1] |

| Undergraduates | 18,969 |

| Postgraduates | 4,286 |

| Location | , |

| Campus | Urban |

| Affiliations | EUA |

| Website | www.vu.lt |

Vilnius University (Lithuanian: Vilniaus universitetas) is the oldest university in the Baltic states and one of the oldest in Eastern Europe. It is also the largest university in Lithuania.

Names

The university has been known under various names during its history:

- 1579–1782: Jesuit Academy of Vilnius (Alma Academia et Universitas Vilnensis Societatis Iesu)

- 1782–1803: Principal School of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (Schola Princeps Magni Ducatus Lithuaniae)

- 1803–1832: Vilnius Imperial University (Imperatoria Universitas Vilnensis)

- 1919–1939: University of Stefan Batory

- 1939–1943: Vilnius University

- 1944–1955: Vilnius State University

- 1955–1990: Vilnius State University of Vincas Kapsukas

- 1971–1979: Vilnius Order of the Red Banner of Labour State University of Vincas Kapsukas (Vilniaus Darbo raudonosios vėliavos ordino valstybinis Vinco Kapsuko universitetas)

- 1979–1990: Vilnius Orders of the Red Banner of Labour and Friendship of Peoples State University of Vincas Kapsukas (Vilniaus Darbo raudonosios vėliavos ir Tautų draugystės ordinų valstybinis V. Kapsuko universitetas)

- Since 1990: Vilnius University

History

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

In 1568, the Lithuanian nobility[1] asked the Jesuits to create an institution of higher learning either in Vilnius or Kaunas. The following year Walerian Protasewicz, the bishop of Vilnius, purchased several buildings in the city center and established the Vilnian Academy (Almae Academia et Universitas Vilnensis Societatis Jesu). Initially, the Academy had three divisions: humanities, philosophy, and theology. The curriculum at the College and later at the Academy was taught in Latin.[2] At the beginning of 17th century there are records about special groups that taught Lithuanian speaking students Latin, most probably using Konstantinas Sirvydas' compiled dictionary.[3] The first students were enrolled into the Academy in 1570. A library at the college was established in the same year, and Sigismund II Augustus donated 2500 books to the new college.[1] In its first year of existence the college enrolled 160 students.[1]

On April 1, 1579, Stefan Batory King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, upgraded the academy and granted it equal status with the Kraków Academy, creating the Alma Academia et Universitas Vilnensis Societatis Iesu. His edict was approved by Pope Gregory XIII's bull of October 30, 1579. The first rector of the Academy was Piotr Skarga. He invited many scientists from various parts of Europe and expanded the library, with the sponsorship of many notable persons: Sigismund II Augustus, Bishop Walerian Protasewicz, and Kazimierz Lew Sapieha. Lithuanians at the time comprised about one third of the students (in 1568 there were circa 700 students), others were Germans, Poles, Swedes, and even Hungarians.[1]

In 1575, Duke Mikołaj Krzysztof Radziwiłł and Elżbieta Ogińska sponsored a printing house for the academy, one of the first in the region. The printing house issued books in Latin and Polish and the first surviving book in Lithuanian printed in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was in 1595. It was entitled Kathechismas, arba Mokslas kiekvienam krikščioniui privalus, and was authored by Mikalojus Daukša.

The Academy's growth continued until the 17th century. The following era, known as The Deluge, led to a dramatic drop in both the number of students that matriculated, and in the quality of its programs. In the middle of the 18th century, educational authorities tried to restore the Academy. This led to the foundation of the first observatory in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, (the fourth such professional facility in Europe), in 1753, by Tomasz Żebrowski. The Commission of National Education (Komisja Edukacji Narodowej), the world's first ministry of education, took control of the Academy in 1773, and transformed it into a modern University. Thanks to the Rector of the Academy, Marcin Poczobutt-Odlanicki, the Academy was granted the status of Principal School (Szkoła Główna) in 1783. The Commission, the secular authority governing the academy after the dissolution of the Jesuit order, drew up a new statute. The school was named Academia et Universitas Vilnensis.

Partitions

After the Partitions of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Vilnius was annexed by the Russian Empire. However, the Commission of National Education retained control over the Academy until 1803, when Tsar Alexander I of Russia accepted the new statute and renamed the Academy to The Imperial University of Vilna (Императорскiй Виленскiй Университетъ). The institution was granted the rights to the administration of all educational facilities in the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Among the notable personae were the curator (governor) Adam Jerzy Czartoryski, and Rector Jan Śniadecki.

The University flourished. By 1823, it was one of the largest in Europe; the number of students exceeded that of the Oxford University. A number of students were arrested in 1823 for conspiracy against the Tsar (membership in Filomaci). Among them was Adam Mickiewicz, who later became one of the most important poets of his time. In 1832, after the November Uprising, the University was closed by Tsar Nicholas I of Russia.

Two of the faculties were turned into separate schools: the Medical and Surgical Academy (Akademia Medyko-Chirurgiczna) and the Roman Catholic Academy (Rzymsko-Katolicka Akademia Duchowna), but those were soon banned as well. The repression that followed the failed uprising included banning both the Polish and Lithuanian languages, and all education in those languages was halted. Finally, most of the property of the University was confiscated and sent to Russia (mostly to St. Petersburg).

1918-1939

Lithuania declared its independence in February 1918. The university, along with the rest of Vilnius and Lithuania, was opened three times between 1918 and 1919 by different powers. The Lithuanian National Council re-established it in December 1918, with classes to start on January 1, 1919. An invasion by the Red Army interrupted this plan. A Lithuanian communist, Vincas Kapsukas-Mickevičius, then sponsored a plan to re-open it as "Labor University" in March 1919, but the city was taken by Poland in April 1919. Marshall Józef Piłsudski reopened it as Stefan Batory University (Uniwersytet Stefana Batorego) on August 28, 1919. The Vilnius Region was subsequently annexed by Poland. In response to the dispute over the region, many Lithuanian scholars moved to Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas, the interwar capital.[4]

The University quickly recovered and gained international prestige, largely because of the presence of notable scientists such as Władysław Tatarkiewicz, Marian Zdziechowski, and Henryk Niewodniczański. Among the students of the University at that time was future Nobel prize winner Czesław Miłosz. The University grew quickly, thanks to government grants and private donations. Its library contained 600,000 volumes, including historic and cartographic items which are still in its possession.[4]

In 1938 the University had:

- 7 Institutes

- 123 professors

- 104 different scientific units (including two hospitals)

- 3110 students

The University's international students included 212 Russians, 94 Belarusians, 85 Lithuanians, 28 Ukrainians and 13 Germans.

World War II

Following the Invasion of Poland (1939) the University did not stop teaching. The city was soon occupied by the Soviet Union. Most of the professors returned to the university after the hostilities ended, and the faculties reopened on October 1, 1939. On October 28, Vilnius was transferred to Lithuania which considered the previous eighteen years as an occupation by Poland of its capital.[5] The University was closed on December 15, 1939 by the authorities of the Republic of Lithuania. All the University staff and its approximately 3,000 students dismissed.[6] Following the Lithuanization policies, in its place a new university, named Vilniaus Universitetas, was created. The new University Charter specified that Vilnius University was to be governed according to the statute of the Vytautas Magnus University of Kaunas, and that Lithuanian language programs and faculties would be established. Lithuanian language was named as the official language of the university. Law and Social Sciences, Humanities, Medical, Theological, Mathematical-Life sciences faculties continued to work underground [7]. Soon after the annexation of Lithuania by the Soviet Union, while some Polish professors were allowed to resume teaching, many others (along with some Lithuanian professors) who were deemed reactionary were arrested and sent to prisons and gulags in Russia and Kazakhstan. Between September 1939, and July 1941, the Soviets arrested and deported nineteen Polish faculty and ex-faculty of the University of Stefan Batory, of which nine perished: Professors Stanisław Cywinski, Wladyslaw Jakowicki, Jan Kempisty, Józef Marcinkiewicz, Tadeusz Kolaczynski, Piotr Oficjalski, Wlodzimierz Godlowski, Konstanty Pietkiewicz, and Konstanty Sokol-Sokolowski, the last five victims of the Katyn massacre.[6]

The city was occupied by Germany in 1941, and all institutions of higher education for Poles were closed. However, the remaining Polish professors organized a system of secret education with lectures and exams held in private flats. The diplomas of the underground Universities were accepted by many Polish Universities after the War. In 1944, many of the students took part in Operation Ostra Brama. The majority of the them were later arrested by the NKVD and deported to the Soviet Union. From 1940 until September 1944, under Lithuanian professor and activist Mykolas Biržiška, the University of Vilnius was open for Lithuanian students under supervision of the German occupation authorities [8].

Soviet period (1945-1990)

Educated Poles were transferred to People's Republic of Poland after World War II under the guidance of State Repatriation Office. As the result many of former students and professors of Stefan Batory joined various universities in Poland. In order not to lose contact with each other, the professors decided to transfer whole faculties. After 1945, most of the mathematicians, humanists and biologists joined the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, while a number of the medical faculty formed the core of the newly-founded Medical University of Gdańsk. The Toruń university is often considered to be the successor to the Polish traditions of the Stefan Batory University.

In 1955[9] the University was named after Vincas Kapsukas. After it had been awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labour in 1971 and the Order of Friendship of Peoples in 1979, its full name until 1990 was Vilnius Order of the Red Banner of Labour and Order of Friendship of Peoples V. Kapsukas State University.[9] Though restrained by the Soviet system, Vilnius University grew and gained significance and developed its own, Lithuanian identity. Vilnius University began to free itself from Soviet ideology in 1988, thanks to the policy of glasnost.

After 1990

On March 11, 1990, Lithuania declared independence, and the University regained autonomy. Since 1991, Vilnius University has been a signatory to the Magna Charta of the European Universities. The University is a member of the European University Association (EUA) and the Conference of Baltic University Rectors.

Vilnius University today

In modern times, the University still offers studies with an internationally recognized content.

As of January 1, 2007, there were 23,255 students studying at Vilnius University[10].

The current University Rector is Professor Benediktas Juodka of the Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics.

The University, specifically the courtyard, was featured in the American TV series the Amazing Race

Organization

There are 12 faculties:

- Chemistry

- Economics

- Philology

- Philosophy

- Physics

- Natural Sciences

- History

- Kaunas Faculty of Humanities

- Communication Website

- Mathematics and Informatics

- Medicine

- Law

The university has a number of semi-autonomous institutes:

- Institute of International Relations and Political Science

- Institute of Material Science and Applied Research

- Institute of Foreign Languages

- Institute of Ecology

- Institute of Immunology

- Institute of Theoretical Physics and Astronomy

- Institute of Oncology

- Institute of Experimental and Clinical Medicine

- UNESCO Associated Centre of Excellence for Research and Training in Basic Sciences

- The Vilnius Yiddish Institute

There are also several study and research centers at Vilnius University:

- A.J.Greimas Center of Semiotics

- Environmental Studies Center

- Center for Stateless Cultures

- Center of Orientalistics

- Center of Professional Improvement

- Religious Studies and Research Centre

- Sports Center

- Center for Gender Studies

- Vilnius Distance Education Study Center

- Center of Excellence in Cell Biology and Lasers

Projects

A complete list of research projects may be found at [2]. Recent and ongoing projects at Vilnius University include:

- "Laser Spectrometer for Testing of Coatings of Crystals and Optical Components in Wide Spectral and Angle Range"[11]. NATO Science for Peace programme project. NATO SfP-972534. 1999-2002.

- "Cell biology and lasers: towards new technologies". Vilnius University - UNESCO Associated Centre of Excellence.[12]

- "Science and Society: Genomics and Benefit Sharing with Developing Countries - From Biodiversity to Human Genomics (GenBenefit)". Doc. E. Gefenas (Faculty of Medicine). 2006-2009.

- "Citizens and governance in a knowledge-based society: Social Inequality and Why It Matters for the Economic and Democratic Development of Europe and Its Citizens. Post-Communist Central and Eastern Europe in Comparative Perspective (EUREQUAL)." Doc. A. Poviliūnas (Faculty of Philosophy). 2006-2009.

- "Marie Curie Chairs: Centre for Studies and Training Experiments with Lasers and Laser Applications (STELLA)". A. Dubietis (Faculty of Physics). 2006-2009.

- "Research Infrastructure Action: Integrated European Laser Laboratories (LaserLab-Europe)". Prof. A. Piskarskas (Faculty of Physics). 2004-2007.

- "Nanotechnology and nanoscieces, knowledge-based multifunctional materials, new production processes and devices: Cell Programming by Nanoscaled Devices (CellPROM)". Prof. A. Kareiva (Faculty of Chemistry). 2004-2009.

Nobel Prize winners

- Czesław Miłosz, poet, The Nobel Prize in Literature 1980

Notable professors and alumni of Vilnius University

- Sorted in alphabetical order

- Michał Bobrowski

- Brigita Brazytė, linguist

- Alfredas Bumblauskas, professor, historian

- Ludwik Chmaj, historian and philosopher

- Aleksander Chodźko, poet, Slavist

- Leonard Chodźko, historian

- Józef Michał Chomiński, musicologist

- Adam Jerzy Czartoryski

- Tadeusz Czeżowski, logician

- Simonas Daukantas, historian

- Ignacy Domeyko, founder of University of Santiago de Chile

- Henryk Elzenberg, historian and philosopher

- Józef Gołuchowski, philosopher

- Gottfried Erns Groddeck, medician

- Johann Peter Frank, medician

- Josef Frank, medician

- Marija Gimbutas, archeologist, author of the Kurgan hypothesis

- Edvardas Gudavičius, professor, historian

- Tomasz Hussarzewski, historian

- Stanisław Bonifacy Jundziłł, biologist

- Daniel Klein, the author of the first grammar book of the Lithuanian language

- Ludwik Kolankowski, historian

- Józef Ignacy Kraszewski, writer

- Michał Kulesza (Mykolas Kuleša), painter

- Žygimantas Liauksminas, philosopher

- Joachim Lelewel, historian and politician

- Henryk Łowmiański, historian

- Ina Marciulionyte, Ambassador and Permanent Delegate of the Republic of Lithuania to UNESCO

- Adam Mickiewicz, poet

- Czesław Miłosz, poet, Nobel laureate

- Kazimierz Moszyński, ethnologist

- Ignacy Żegota Onacewicz, Polish scientist and Belarusian national revival pioneer

- Jan Szczepan Otrębski, philologist, professor of Lithuanian and German languages

- Karol Podczaszyński, architect

- Edmundas Rimša historian, specialist of heraldics, sfragistics and genealogy.

- Maciej Kazimierz Sarbiewski, famous Latin language poet

- Józef Sękowski, orientalist, journalist

- Piotr Skarga

- Kazimierz Siemienowicz, artillery engineer, constructor and pioneer of rocketry

- Konstantinas Sirvydas, professor

- Juliusz Słowacki, poet

- Stefan Srebrny, philologist

- Jan Śniadecki, astronomer, mathematician, physicist

- Jędrzej Śniadecki, chemist and medician

- Marcin Śmiglecki, logician

- Witold Taszycki, linguist

- Józef Trypućko, philologist

- Tomas Venclova, poet, author and translator, Yale University professor

- Albertas Vijūkas-Kojelavičius, historian, author of the first History of Lithuania

- Vilenas Vadapalas, lawyer, Judge in the Court of First Instance

- Stanislaw Warszewicki, writer

- Jan Fryderyk Wolfgang, biologist

- Jakub Wujek, first translator of the Bible into the Polish language

- Tomasz Zan, poet

- Zigmas Zinkevičius, professor, linguist-historian.

Honorary Doctorates conferred by Vilnius University

- Józef Kallenbach, Polish historian of literature (1927)

- Władysław Abraham [7]

- Władysław Leopold Jaworski

- Ignacy Koschembahr-Łyskowski

- Stanisław Kutrzeba

- Leon Petrażycki

- Stanisław Starzyński

- Franciszek Zoll

- Henri Berthelemy

- Paul Fournier

- Pierro Bonfante

- Salvatore Riccobono

- Karl Stooss

- Ludvig Puusepp, Estonian neurosurgeon (1930) [13]

- Jan Safarewicz, Full Member of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Professor, Cracow Jagellonian University (1979)

- Zdenek Češka, Associate Member of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Rector of Charles University, Prague (1979)

- Werner Scheler, Professor, Germany (1979)

- Boris Levit, Professor, Moldova

- Valdas Adamkus, President of Lithuania (1989)

- Czeslaw Olech, Director of International Mathematical Banach Centre, Member of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Professor, Warsaw University (1989)

- Christian Winter, Professor, Frankfurt am Main University (Germany) (1989)

- Vaclovas Dargužas (Andreas Hofer), Doctor of Medicine (Switzerland) (1991)

- Edvardas Varnauskas, Doctor of Medicine, Professor (Sweden) (1992)

- Martynas Yčas, Professor, New York State University (1992)

- Paulius Rabikauskas, Professor, Gregorius University (Rome, Italy) (1994)

- Tomas Remeikis, professor, Indiana Calumet College (USA) (1994)

- William Schmalstieg, Professor, Pennsylvania State University (USA) (1994)

- Vladimir Toporov, Professor, Institute of Slavonic Languages, Russian Academy of Sciences (1994)

- Václav Havel, President of the Czech Republic (1996)

- Alfred Laubereau, Head of the Experimental Physics Department, Munich Technical University, Professor, Bairoit University (1997)

- Nikolaj Bachalov, Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Head of the Computational Mathematics Department, Faculty of Mathematics, Moscow M. Lomonosov University (1997)

- Rainer Eckert, Professor, Director of the Institute of Baltic Studies, Greifswald University (1997)

- Juliusz Bardach, Professor, Warsaw University (Poland) (1997)

- Theodor Hellbrugge, founder and Head of the Munich Children Centre, Institute of Social Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Professor, Munich University (Germany) (1998)

- Friedrich Scholz, Director of the Interdisciplinary Institute of Baltic Studies, Professor, Munich University (Germany) (1998)

- Zbigniew Brzezinski, Professor, Advisor of the government of USA (1998)

- Maria Wasna, Doctor, Professor, psychologist, Rector of Münster University (Germany) (1999)

- Ludwik Piechnik, Professor of History, Cracow Papal Theological Academy (Poland) (1999)

- Sven Lars Caspersen, Professor of Economics, President of the World Rector's Association, Rector of Aalborg University (Denmark) (1999)

- Wolfgang P. Schmid, Professor, Göttingen University (Germany) (2000)

- Eduard Liubimskij, Professor, Moscow University (Russia) (2000)

- Andrzej Zoll, Professor, Jagellonian University in Kraków (Poland) (2002)

- Dagfinn Moe, Professor, Bergen University (Norway) (2002)

- Jurij Stepanov, Professor, Moscow University (Russia) (2002)

- Ernst Ribbat, Professor, Münster University (Germany) (2002)

- Sven Ekdahl, Professor, Prussian Secret Archives in Berlin (Germany) (2004)

- Peter Ulrich Sauer, Professor, Hanover University (Germany) (2004)

- Peter Gilles, Professor, Johann Wolfgang Goethe University (Frankfurt am Main, Germany) (2004)

- Francis Robicsek, Professor, Carolinas Heart Institute at Carolinas Medical Centre in Charlotte, North Carolina (USA) (2004)

- Aleksander Kwaśniewski, President of the Republic of Poland (2005)

- Vladimir P. Skulachev, Professor, Moscow M. Lomonosov University (Russia) (2005)

- Vassilios Skouris, Professor, President of the European Court of Justice (2005)

- Pietro Umberto Dini, Professor, University of Pisa (Italy) (2005)

- Jacques Rogge, President of the International Olympic Committee (2006)

- Gunnar Kulldorff, Professor, Umeå University (Sweden) (2006)

- Reinhardt Bittner, Professor, Tübingen University Academic Hospital in Stuttgart (Germany) (2007)

- Wojciech Smoczyński, Professor, Jagiellonian University in Kraków (Poland) (2007)

- Georg Völkel, Professor, University of Leipzig (Germany) (2008)

- Helmut Kohl, Professor, Johann Wolfgang Goethe University Frankfurt am Main (Germany) (2008)

Bibliography

- Studia z dziejów Uniwersytetu Wileńskiego 1579–1979, K. Mrozowska, Kraków 1979

- Uniwersytet Wileński 1579–1979, M. Kosman, Wrocław 1981

- Vilniaus Universiteto istorija 1579–1803, Mokslas, Vilnius, 1976, 316 p.

- Vilniaus Universiteto istorija 1803–1940, Mokslas, Vilnius, 1977, 341 p.

- Vilniaus Universiteto istorija 1940–1979, Mokslas, Vilnius, 1979, 431 p.

- Łossowski, Piotr (1991). Likwidacja Uniwersytetu Stefana Batorego przez władze litweskie w grudniu 1939 roku (in Polish). Warszawa: Interlibro. ISBN 8385161260.

See also

- List of Universities in Lithuania

- Protmušis

- Start FM

- History of Vilnius

- Vilnius University Folklore Ensemble "Ratilio"

References

- ^ a b c d Template:Lt iconZinkevičius, Zigmas (1988). Lietuvų kalbos istorija (Senųjų raštų kalba). Vilnius: Mintis. p. 159. ISBN 5-420-00102-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Template:Lt iconZinkevičius, Zigmas (1988). Lietuvų kalbos istorija (Senųjų raštų kalba). Vilnius: Mintis. p. 160. ISBN 5-420-00102-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Template:Lt iconZinkevičius, Zigmas (1988). Lietuvų kalbos istorija (Senųjų raštų kalba). Vilnius: Mintis. p. 161. ISBN 5-420-00102-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Tomas Venclova. FOUR CENTURIES OF ENLIGHTENMENT:A Historic View of the University of Vilnius, 1579-1979. Lituanus.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ D. Trenin. The End of Eurasia: Russia on the Border Between Geopolitics and Globalization. 2002, p.164

- ^ a b Adam Redzik, Polish Universities During the Second World War, Encuentros de Historia Comparada Hispano-Polaca / Spotkania poświęcone historii porównawczej hiszpańsko-polskiej conference, 2004

- ^ a b Template:Pl icon Mikołaj Tarkowski, Wydział Prawa i Nauk Społecznych Uniwersytetu Stefana Batorego w Wilnie 1919-1939, - przyczynek do dziejów szkolnictwa wyższego w dwudziestoleciu międzywojennym

- ^ History

- ^ a b History

- ^ Facts and Figures – Vilnius University

- ^ Laser Research Center

- ^ Research - News Centre

- ^ Biblioteka Uniwersytecka UMK. Dokumenty Życia Społecznego

External links

- Vilnius University homepage

- Universitas Vilnensis 1579-2004, well written and illustrated book (92 pages)

- The Vilnius Yiddish Institute

- History of Vilnius University by Tomas Venclova

- Template:Pl icon Uniwersytet Wileński 1579-2004

- Template:Pl icon Album obchodu 350-lecia Uniwersytetu Stefana Batorego w Wilnie, Wilno 1928

- Utrecht Network