History of Shiraz

The city of Shiraz, Iran is more than 4000 years old.

Pre-Islamic times

Shiraz is founded in Pars Province, a central area for Persian civilisation. The earliest reference to Shiraz is on Elamite clay tablets dated to 2000 BC, found in June 1970 during digging for the construction of a brick kiln in the southwest corner of the city. The tablets, written in ancient Elamite, name a city called Tiraziš.[1] Phonetically, this is interpreted as /tiračis/ or /ćiračis/. This name became Old Persian /širājiš/; through regular sound change comes the modern Persian name Shirāz. The name Shiraz also appears on clay sealings found at Qasr-i Abu Nasr, a Sassanid ruin, east of the city, (2nd century AD). As early as the 11th century several hundred thousand people inhabited Shiraz. Its size has decreased through the ages.[clarification needed]

Cuneiform records from Persepolis show that Shiraz was a significant township in Achaemenid times.[2]

There is mention of a city at Shiraz during the Sassanid era, (2nd to 6th century AD) in the 10th century geographical treatise Hudud ul-'alam min al-mashriq ila al-maghrib, which reports the existence of two fire temples and a fortress called "Shahmobad". In the 14th century the Nozhat ol-Qolub of Hamdollah Mostowfi confirmed the existence of pre-Islamic settlements in Shiraz.

Islamic period

The city became a provincial capital in 693, after the Arabs conquered Istakhr, the nearby Sassanian capital. As Istakhr fell into decline, Shiraz grew in importance under the Arabs and several local dynasties.[3] The Buwayhid dynasty (945 — 1055) made it their capital, building mosques, palaces, a library and an extended city wall.

The city was spared destruction by the invading Mongols when its local ruler offered tributes and submission to Genghis Khan. Shiraz was again spared by Tamerlane when in 1382 the local monarch, Shah Shoja agreed to submit to the invader.[3] In the 13th century, Shiraz became a leading center of the arts and letters, thanks to the encouragement of its ruler and the presence of many Persian scholars and artists. For this reason the city was named by classical geographers Dar al-Elm, the House of Knowledge.[4] Among the important Iranian poets, mystics and philosophers born in Shiraz were the poets Sa'di and Hafiz the mystic Roozbehan and the philosopher Mulla Sadra.

As early as the 11th century, several hundred thousand people inhabited Shiraz.[5] In the 14th century Shiraz had sixty thousand inhabitants.[6] During the 16th century it had a population of 200,000 people, which by the mid-18th century had decreased to only 50,000.

In 1504 Shiraz was captured by the forces of Ismail I, the founder of the Safavid dynasty. Throughout the Safavid empire (1501–1722) Shiraz remained a provincial capital and Emam Qoli Khan, the governor of Fars under Shah Abbas I, constructed many palaces and ornate buildings in the same style as those built in the same period in Isfahan, the capital of the Empire.[3] After the fall of the Safavids, Shiraz suffered a period of decline, worsened by the raids of the Afghans and the rebellion of its governor against Nader Shah; the latter sent troops to suppress the revolt. The city was besieged for many months and eventually sacked. At the time of Nader Shah's murder in 1747 most of the historical buildings of the city were damaged or ruined, and its population fell to 50,000, a quarter of that of the 16th century.[3]

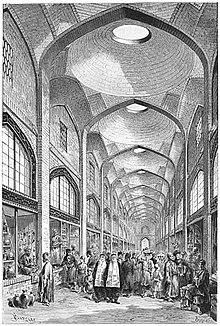

Shiraz soon returned to prosperity under the enlightened rule of Karim Khan Zand who made it his capital in 1762. Employing more than 12,000 workers he constructed a royal district with a fortress, many administrative buildings, a mosque and one of the finest covered bazaars in Iran.[3] He had a moat built around the city, constructed an irrigation and drainage system, and rebuilt the city walls.[3] However, Karim Khan's heirs failed to secure his gains. When Agha Mohammad Khan, the founder of the Qajar dynasty, eventually came to power, he wreaked his revenge on Shiraz by destroying the city fortification and moving the national capital to Sari.[3] Although lowered to the rank of provincial capital, Shiraz maintained a level of prosperity as a result of the continuing importance of the trade route to the Persian Gulf and its governorship was a royal prerogative throughout the Qajar dynasty.[3] many of the famous gardens, buildings and residences built during the nineteenth century, contribute to the actual outlook of the city.

Shiraz is the birthplace of the founder of the short-lived Babi movement, the Báb (Sayyid `Ali-Muhammad Shirazi, 1819-1850). In this city, on the evening of 22 May 1844, he began discussions that led to his claiming to be an interpreter of the Qur'an, the first of several progressive claims between then and 1849. Since the Báb is considered a 'forerunner' of the Baháʼí Faith, Shiraz is a holy city for Bahá’ís, where the Báb's House (demolished in 1979 by the Islamic regime) was a putative pilgrimage site.

In 1910 a pogrom of the Jewish quarter started after false rumours that the Jews had ritually killed a Muslim girl. In the course of the pogrom, 12 Jews were killed and about 50 were injured,[7] and 6,000 Jews of Shiraz were robbed of all their possessions.[8]

The city's role in trade greatly diminished with the opening of the trans-Iranian railway in the 1930s, as trade routes shifted to the ports in Khuzestan. Much of the architectural inheritance of Shiraz, and especially the royal district of the Zands, was either neglected or destroyed as a result of irresponsible town planning under the Pahlavi dynasty. Lacking any great industrial, religious or strategic importance, Shiraz became an administrative centre, although its population has grown considerably since the 1979 revolution.[9]

Recent history

Recently many historical sites in the city were renovated. But in 1979, the Islamic regime demolished the beautifully restored house that had belonged to Sayyid 'Ali Muhammad Shirazi, the Bab, and built a mosque on the site. The Shiraz International Airport is expanded.

Agriculture has always been a major part of the economy in and around Shiraz. This is partially due to a relative abundance of water compared to the surrounding deserts. The Gardens of Shiraz and "Evenings of Shiraz" are famous throughout Iran and the middle east. The moderate climate and the beauty of the city has made it a major tourist attraction.

Shiraz is also home to many Iranian Jews, although most have immigrated to the United States and Israel in the last half of the twentieth century, particularly after the Islamic Revolution. Along with Tehran and Esfahan Shiraz is one of the handful of Iranian cities with sizable Jewish populations and more than one active synagogue.

The municipality of Shiraz and the related cultural institutions have promoted and carried out many important restoration and reconstruction projects through the city.[3] Among the most recent ones are the complete restoration of the Arg of Karim Khan and of the Vakil Bath as well as a comprehensive plan for the preservation of the old city quarters. Other noteworthy initiatives of the municipality include the total renovation of the Qur'an Gate and the mausoleum of the poet Khwaju Kermani, both located in the Allahu Akbar Gorge, as well as the grand project of expansion of the mausoleum of the world-famous poet Hafiz.[3]

Timeline

References

- ^ Cameron, George G. This is wrongTreasury Tablets, University of Chicago Press, 1948, pp. 115.

- ^ "Fárs and Shíráz"[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "History of Shiraz". Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ (pdf file)

- ^ "Shiraz, Iran" Archived 2007-12-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (Google book search)

- ^ Littman (1979), p. 14

- ^ Littman (1979), p. 12

- ^ Shiraz History - Shiraz Travel Guide - Lonely Planet