Battle of the Paracel Islands

| Battle of the Paracel Islands | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Vietnam War | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

2 minesweepers (#271 and #274) 2 submarine chasers (#389 and #396)[1] Unknown number of marines Unknown number of maritime militia |

3 frigates 1 corvette 1 commando platoon 1 demolition team 1 militia platoon | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

18 killed 67 wounded 2 minesweepers damaged 2 submarine chasers damaged |

75 killed 16 wounded 48 captured 1 corvette sunk 3 frigates damaged[2] | ||||||||

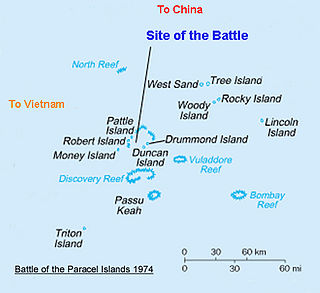

The Battle of the Paracel Islands (Chinese: 西沙海战, Pinyin: Xisha Haizhan;Vietnamese: Hải chiến Hoàng Sa) was a military engagement between the naval forces of China and South Vietnam in the Paracel Islands on January 19, 1974. The battle was an attempt by the South Vietnamese navy to expel the Chinese navy from the vicinity. The confrontation took place towards the end of the Vietnam War.

Prior to the conflict, part of the Paracel Islands was controlled by China and another part was controlled by South Vietnam. As a result of the battle, the PRC occupied the South Vietnamese portion and established full de facto control over the Paracels.

Background

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

The Paracel Islands, called Xisha Islands (西沙群岛; Xīshā Qúndǎo) in Chinese and Hoang Sa Islands (Quần Đảo Hoàng Sa) in Vietnamese, lie in the South China Sea approximately equidistant from the coastlines of the PRC and Vietnam (200 nautical miles or 370 km). With no native population, the archipelago’s ownership has been in dispute since the early 20th century.

The 1874 Treaty of Saigon effectively made Vietnam a protectorate of France. This led to a confrontation between France and China in 1884–5. The Convention Respecting the Delimitation of the Frontier between China and Tonkin was concluded between France and China on 26 June 1887,[3] allocating islands east of the eastern point of Tra Co island (21°30′N 108°4′E / 21.500°N 108.067°E).[4] This point lies on a north–south line far to the west of the Paracels.[5] Though the treaty has ambiguities, Chinese officials have interpreted it as granting Beijing ownership and control of the Paracel and Spratly Islands.[3]: 389

In a letter dated 4 May 1919 the Consul of France in Canton to the French Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Consul mentioned an incident in which a request to the Chinese government for compensation by the British government arising out of a shipwreck in the Paracels had been rejected by the Chinese government, "precisely on the ground that the Paracels were not part of the Chinese empire."[6]

In 1932, one year after the Japanese Empire invaded northeast China, France formally claimed both the Paracel and Spratly Islands; China and Japan both protested. In 1933, France bolstered their claim and seized the Paracels and Spratlys, announced their annexation, and formally included them in French Indochina. They built several weather stations on them.

In 1938 Japan took the islands from France, garrisoned them, and built a submarine base at Itu Aba (now Taiping / 太平) Island. In 1941, the Japanese Empire made the Paracel and Spratly Islands part of Taiwan, then under its rule.

In 1945, in accordance with the Cairo and Potsdam Declarations and with American help, the armed forces of the Republic of China (ROC) accepted the surrender of the Japanese garrisons in Taiwan-including the Paracel and Spratly Islands and declared both archipelagoes to be part of Guangdong Province. In 1946 the ROC established garrisons on both Woody (now Yongxing / 永兴) Island in the Paracels and Taiping Island in the Spratlys. France promptly protested.

The French tried but failed to dislodge Chinese nationalist troops from Yongxing Island (the only habitable island in the Paracels), and established a small camp on Pattle (now Shanhu / 珊瑚) Island in the southwestern part of the archipelago.[7]

In 1950, after the Chinese nationalists were driven from Hainan by the People's Liberation Army (PLA), the ROC withdrew their garrisons in both the Paracels and Spratlys to Taiwan. In 1954, France ceased to be a factor when it accepted the independence of both South and North Vietnam and withdrew from Indochina.

In 1956 the PLA reestablished a Chinese garrison on Yongxing Island, while the Republic of China (Taiwan) stationed troops on Taiping Island. That same year, South Vietnam reestablished the abandoned French camp on Pattle Island and announced it had annexed the Paracel archipelago as well as the Spratlys. To focus on its war with the North, South Vietnam reduced its presence on the Paracels to only a single weather observation garrison on Pattle Island by 1966. The PLA made no attempt to remove this force.[8][page needed]

In 1958, North Vietnam sent a diplomatic note to China acknowledging and approving the declaration made by China which defined Chinese territorial waters. One English translation of the note reads, "the Vietnamese government approves of the declaration ... and will give all state organs concerted directives aimed at ensuring strict respect of Chinese territorial water fixed at 12 nautical miles in all relations with China at Sea."[9]

Prelude

On January 16, 1974, six South Vietnamese Army officers and an American observer on the frigate Lý Thường Kiệt (HQ-16) were sent to the Paracels on an inspection tour. They discovered two Chinese “armored fishing trawlers” laying off Drummond Island to support a detachment of PLA troops who had occupied the island. Chinese soldiers were also observed around a bunker on nearby Duncan Island, with a landing ship moored on the beach and two additional Kronstadt-class submarine chasers in the vicinity. This was promptly reported to Saigon,[10][11] and several naval vessels were sent to confront the Chinese ships in the area.

The South Vietnamese Navy frigate signaled the Chinese squadron to withdraw, and in return received the same demand. The rival forces shadowed each other overnight, but did not engage.

On January 17, about 30 South Vietnamese commandos waded ashore unopposed on Robert Island and removed the Chinese flag they found flying. Later, both sides received reinforcements. The frigate Trần Khánh Dư (HQ-4) joined the Lý Thường Kiệt (HQ-16), while two PLA Navy minesweepers (#274 and #271) joined the Chinese.

On January 18, the frigate Trần Bình Trọng (HQ-5) arrived carrying the commander of the South Vietnamese fleet, Colonel Hà Văn Ngạc. The corvette Nhật Tảo (HQ-10) also reached the islands, moving cautiously because it had only one functioning engine at the time.

Balance of forces

Four warships from the South Vietnam Navy would participate in the battle: the frigates, Trần Bình Trọng,[1] Lý Thường Kiệt,[2] and Trần Khánh Dư,[3] and the corvette Nhật Tảo.[4] A platoon of South Vietnamese naval commandos, an underwater demolition team, and a regular ARVN platoon were by now stationed on the islands.

China also had four warships present: the PLA Navy minesweepers 271, 274, 389 and 396. These were old and small warships with an average length of 49 meters (161 ft) and width of 6 meters (20 ft), and they had not been well-maintained. They were reinforced by two Type 037 submarine chasers (281 and 282) by the end of the battle. In addition, two PLA marine battalions and an unknown number of irregular militia had been landed on the islands. The 48th Aviation Division of the People's Liberation Army Air Force provided some air support.[12]

Although four ships were engaged on each side, the total displacements and weapons of the South Vietnamese ships were superior. The supporting and reinforcement forces of the PLA Navy did not take part in the battle.

Military engagement

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

In the early morning of January 19, 1974, South Vietnamese soldiers from Trần Bình Trọng landed on Duncan Island and came under fire from Chinese troops. Three South Vietnamese soldiers were killed and more were wounded. Finding themselves outnumbered, the South Vietnamese ground forces withdrew by landing craft, but their small fleet drew close to the Chinese warships in a tense standoff.

At 10:22 a.m., the South Vietnamese warships Lý Thường Kiệt (HQ-16) and Nhật Tảo (HQ-10) moved in the battle zone, shortly followed by Trần Bình Trọng (HQ-5) and Trần Khánh Dư (HQ-4). At 10:24 a.m., the HQ-10 and HQ-16 opened fire on the Chinese warships. HQ-4 and HQ-5 then joined in.

After a few minutes, both HQ-4 and HQ-5 stopped firing and moved away from the battle zone because of 'shooting concerns'. HQ-16 was severely damaged by friendly-fire from HQ-5 (commanded by Colonel Ha Van Ngac), causing it to list and become combat ineffective. Le Van Thu, captain of HQ-16, also suspected that HQ-10 might have also been damaged by HQ-4, HQ-5.

The sea battle lasted for about 40 minutes, with vessels on both sides sustaining damage. The smaller Chinese warships managed to maneuver into the blind spots of the main cannons on the South Vietnamese warships and damaged all four South Vietnamese ships, especially HQ-10, which could not retreat because her last working engine was disabled.

The crew was ordered to abandon ship, but her captain, Lieutenant Commander Ngụy Văn Thà, remained on board and went down with his ship. Lý Thường Kiệt, severely damaged by friendly fire from Trần Bình Trọng, was forced to retreat westwards. Trần Khánh Dư and Trần Bình Trọng soon joined in the retreat.

The next day, Chinese aircraft from Hainan bombed the three islands, and an amphibious landing was made. The outnumbered South Vietnamese marine garrison on the islands was forced to surrender, and the damaged navy ships retreated to Đà Nẵng.

During the battle, the South Vietnamese fleet detected two more Chinese warships rushing to the area. China later acknowledged these were the Hainan-class submarine chasers 281 and 282. Despite South Vietnamese reports that at least one of their ships had been struck by a missile, the Chinese insisted what the South Vietnamese saw were rocket-propelled grenades fired by the crew of #389 and that no missile-capable ships were present, and the Chinese ships closed in because they had no missiles. The South Vietnamese fleet also received warnings that U.S. Navy radar had detected additional Chinese guided missile frigates and aircraft on their way from Hainan.

South Vietnam requested assistance from the U.S. Seventh Fleet, but the request was denied.[13][14]

Result

Following the battle, China gained control over all of the Paracel Islands. South Vietnam protested to the United Nations, but China, having veto power on the UN Security Council, blocked any efforts to bring it up.[15] The remote islands had little value militarily, but diplomatically the projection of power was beneficial to China.[16][17]

South Vietnamese casualties

The South Vietnamese reported that the warship Nhật Tảo was sunk and Lý Thường Kiệt heavily damaged, while Trần Khánh Dư and Trần Bình Trọng were both slightly damaged. 53 South Vietnamese soldiers, including Captain Ngụy Văn Thà of Nhật Tảo, were killed, and 16 were wounded. On January 20, 1974, the Dutch tanker, Kopionella, found and rescued 23 survivors of the sunken Nhật Tảo. On January 29, 1974, South Vietnamese fishermen found 15 South Vietnamese soldiers near Mũi Yến (Qui Nhơn) who had fought on Quang Hòa island and escaped in lifeboats.

After their successful amphibious assault on January 20, the Chinese held 48 prisoners, including an American advisor.[5] They were later released in Hong Kong through the Red Cross.

Chinese casualties

The Chinese claimed that even though its ships had all been hit numerous times, none of them had been sunk. Warships 271 and 396 suffered speed-reducing damage to their engines, but both returned to port safely and were repaired. 274 was damaged more extensively and had to stop at Yongxing Island for emergency repairs. It returned to Hainan under its own power the next day.[18]

389 was damaged the most by an engine room explosion. Its captain managed to run his ship aground and put out the fire with the help of the minesweepers. It was then towed back to base. Eighteen Chinese sailors were killed and 67 were wounded in the battle.[18]

Aftermath

A potential diplomatic crisis was averted when China released the American prisoner taken during the battle. Gerald Emil Kosh, 27, a former U.S. Army captain, was captured with the South Vietnamese on Pattle Island. He was described as a “regional liaison officer” for the American embassy in Saigon on assignment with the South Vietnamese Navy.[15] China released him from custody on January 31 without comment.[19][20]

The leaders of North Vietnam gave a glimpse of their worsening relationship with China by conspicuously not congratulating their ally. An official communique issued by the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam mentioned only its desire for a peaceful and negotiated resolution for any local territorial dispute. In the wake of the battle, North Vietnamese Deputy Foreign Minister Nguyễn Cơ Thạch told the Hungarian ambassador to Hanoi that "there are many documents and data on Vietnam's archipelago." Other North Vietnamese cadres told the Hungarian diplomats that in their view, the conflict between China and the Saigon regime was but a temporary one. However, they later said the issue would be a problem of the entire Vietnamese nation.[21]

After the reunification of Vietnam in April 1975, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam publicly renewed its claim to the Paracels, and the dispute continues to this day. Hanoi has praised the South Vietnamese forces that took part in the battle.[22]

See also

Notes

- ^ Security Implications of Conflict in the South China Sea: Exploring Potential Triggers of Conflict A Pacific Forum CSIS Special Report, của Ralph A. Cossa, Washington, D.C. Center for Strategic and International Studies, 1998, trang B-2

- ^ Nhân Dân No. 1653, September 22, 1958 [6]

- ^ Dyadic Militarized Interstate Disputes Data (DyMID), version 2.0 tabulations

- ^ Hải Chiến Hoàng Sa, Bão biển Đệ Nhị Hải Sư, Australia, 1989, page 101

- ^ DyMID

- ^ This warship had been USCGC Chincoteague, and was transferred to South Vietnam and renamed RVNS Trần Bình Trọng (HQ-05). It was transferred to the Philippines and renamed RPS Andrés Bonifacio (PF-7) in 1975 when South Vietnam fell.

- ^ This warship had been USS Bering Strait, and was transferred to South Vietnam and renamed RVNS Lý Thường Kiệt (HQ-16). It was transferred to the Philippines and renamed RPS Diego Silang (PF-9) in 1975 when South Vietnam fell.

- ^ This warship was USS Forster, loaned to South Vietnam on September 25, 1971 and renamed RVNS Trần Khánh Dư (HQ-04). Captured by North Vietnamese after the fall of Saigon and was renamed Dai Ky (HQ-03).

- ^ This warship had been USS Serene, and was transferred to South Vietnam January 24, 1964. It was re-designated as RVNS Nhật Tảo (HQ-10).

- ^ Counterpart, A South Vietnamese Naval Officer's War Kiem Do and Julie Kane, Naval Institute, Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 1998, chương 10.

- ^ Thế Giới Lên Án Trung Cộng Xâm Lăng Hoàng Sa Của VNCH. Tài liệu Tổng cục Chiến tranh Chính trị, Bộ Tổng tham mưu QLVNCH, Sài Gòn, 1974, trang 11.

- ^ 西沙海战――痛击南越海军, Xinhua, January 20, 2003, online

- 西沙海战详解[图], online.

References

- ^ "Tài liệu Trung Quốc về Hải chiến Hoàng Sa: Lần đầu hé lộ về vũ khí". Báo Thanh Niên. January 12, 2014.

- ^ Danh sách các quân nhân Việt Nam Cộng Hòa hi sinh trong Hải chiến Hoàng Sa 1974, Thanh Niên Online, 09/01/2014

- ^ a b Furtado, Xavier (1999). "International Law and the Dispute over the Spratly Islands: Whither UNCLOS?". Contemporary Southeast Asia. 21 (3): 386–404. doi:10.1355/CS21-3D. JSTOR 25798466.

- ^ China Sea Pilot. Hydrographer of the Navy. 1987. p. 203.

- ^ Chemillier-Gendreau 2021, pp. 184-185

- ^ Chemillier-Gendreau 2021, pp. 200, 202, 203.

- ^ Bennett, Michael. The People's Republic of China and the Use of International Law in the Spratly Islands Dispute. pp. 440–441. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ Frivel, M. Taylor. "Offshore Island Disputes". Strong Borders, Secure Nation: Cooperation and Conflict in China's Territorial Disputes. Princeton University Press. pp. 267–299.

- ^ "September 14, 1958 letter from VN Prime Minister Phạm Văn Đồng". Vietnamese Recognition and Support for China's Sovereignty Over Spratly Islands and Paracel Islands Prior to 1975. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ Thomas J. Cutler, The Battle for the Paracel Islands Archived October 8, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD. Retrieved on 4-24-2009.

- ^ Chemillier-Gendreau 2021, p. 3

- ^ "空48师(轰炸航空兵) - 中国空军网 见证中国空军成长历程,关注中国空军建设". November 4, 2014. Archived from the original on November 4, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Cautioned 7th Fleet to Shun Paracels Clash". The New York Times. Reuters. January 22, 1974. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ^ "Chinese, Viet Rift Shunned by U.S." Albuquerque Journal. Albuquerque, NM. AP. January 21, 1974. Retrieved December 22, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Gwertzman, Bernard (January 26, 1974). "Peking Reports Holding U.S. Aide". The New York Times. New York, NY. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- ^ Markham, James M. (January 19, 1974). "Saigon Reports Clash with China". The New York Times. New York, NY. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- ^ Shipler, David K. (January 21, 1974). "Saigon Says Chinese Control Islands, But Refuses to Admit Complete Defeat". The New York Times. New York, NY. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- ^ a b Carl O. Schustser. "Battle for Paracel Islands".

- ^ "The World: Storm in the China Sea - TIME". Archived from the original on December 14, 2007.

- ^ "American Captured on Disputed Island is Freed by China". The New York Times. New York, NY. Reuters. January 31, 1974. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- ^ Balázs Szalontai, Im lặng nhưng không đồng tình. BBC Vietnam, March 24, 2009: http://www.bbc.co.uk/vietnamese/vietnam/2009/03/090324_paracels_hanoi_reassessment.shtml .

- ^ For an overview of Hanoi's reactions to the Chinese occupation of the Paracels in 1974–1975, see also Chi-kin Lo, China's Policy toward Territorial Disputes. The Case of the South China Sea Islands (London and New York: Routledge, 1989), pp. 86–98.

- Chemillier-Gendreau, Monique (2021). Sovereignty over the Paracel and Spratly Islands. Brill. ISBN 9789004479425.

Further reading

- New York Times, "Saigon Says China Bombs 3 Isles and Lands Troops". 1/20/74.

- New York Times, "23 Vietnamese Survivors of Sea Battle Are Found". 1/23/74.

- Yoshihara, Toshi. "The 1974 Paracels Sea Battle: A Campaign Appraisal". Naval War College Review. 69 (2). Naval War College Press: 41–65. Archived from the original on August 1, 2016.

External links

- Overview of the battle by a Vietnamese officer

- The Official Document of The Republic Of Vietnam's Armed Forces about the Paracels Naval Battle in 1974

- Paracels Islands Dispute

- A Collection of Documents on Paracel and Spratly Islands by Nguyen Thai Hoc Foundation Archived August 6, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- GlobalSecurity.org

- Indochina Wars

- History of the Paracel Islands

- Conflicts in 1974

- Naval battles involving China

- Naval battles involving South Vietnam

- 1974 in China

- 1974 in Vietnam

- 20th-century naval battles

- History of the South China Sea

- People's Liberation Army Navy

- Republic of Vietnam Navy

- January 1974 events in Asia

- Wars between China and Vietnam

- China–Vietnam relations

- Military history of Vietnam