Historical European martial arts

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2012) |

Historical European martial arts (HEMA) are martial arts of European origin, particularly using arts formerly practised, but having since died out or evolved into very different forms.

While there is limited surviving documentation of the martial arts of classical antiquity (such as Greek wrestling or gladiatorial combat), most of the surviving dedicated technical treatises or martial arts manuals date to the late medieval period and the early modern period. For this reason, the focus of HEMA is de facto on the period of the half-millennium of ca. 1300 to 1800, with a German, Italian, and Spanish school flowering in the Late Middle Ages and the Renaissance (14th to 16th centuries), followed by French, English, and Scottish schools of fencing in the modern period (17th and 18th centuries).

Bataireacht, or Irish stick fighting, typically with the use of the shillelagh, can be traced back hundreds, even thousands of years, to the sword techniques of the Celts, gaining prominence in the 17th and 18th centuries, as a result of the British occupation of Ireland, thus falling into the category of Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA).

Martial arts of the 19th century such as classical fencing, and even early hybrid styles such as Bartitsu, may also be included in the term HEMA in a wider sense, as may traditional or folkloristic styles attested in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including forms of folk wrestling and traditional stick-fighting methods.

The term Western martial arts (WMA) is sometimes used in the United States and in a wider sense including modern and traditional disciplines. During the Late Middle Ages, the longsword had a position of honour among these disciplines, and sometimes historical European swordsmanship (HES) is used to refer to swordsmanship techniques specifically.

Modern reconstructions of some of these arts arose from the 1890s and have been practiced systematically since the 1990s.

History of European martial arts

Ancient history

The first book about the fighting arts, Epitoma rei militaris[1] , was written into Latin by a Roman writer, Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus, who lived in Rome between the fourth and fifth centuries. There are no other known martial arts manuals predating the Late Middle Ages (except for fragmentary instructions on Greek wrestling, see Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 466), although medieval literature (e.g., sagas of Icelanders, Eastern Roman Acritic songs, the Digenes Akritas and Middle High German epics) record specific martial deeds and military knowledge; in addition, historical artwork depicts combat and weaponry (e.g., the Bayeux Tapestry, the Synopsis of Histories by John Skylitzes, the Morgan Bible). Some researchers have attempted to reconstruct older fighting methods such as Pankration, Eastern Roman hoplomachia, Viking swordsmanship and gladiatorial combat by reference to these sources and practical experimentation.

The Royal Armouries Ms. I.33 (also known as the "Walpurgis" or "Tower Fechtbuch"), dated to ca. 1300,[2] is the oldest surviving Fechtbuch, teaching sword and buckler combat.

Post-classical history

The central figure of late medieval martial arts, at least in Germany, is Johannes Liechtenauer. Though no manuscript written by him is known to have survived, his teachings were first recorded in the late fourteenth-century Nürnberger Handschrift GNM 3227a. From the 15th to the 17th century, numerous Fechtbücher (German "fencing-books") were produced, of which some several hundred are extant; a great many of these describe methods descended from Liechtenauer's. Liechtenauer's Zettel (recital) remains one of the most famous - if cryptic - pieces of European martial arts scholarship to this day, with several translations and interpretations of the poem being put into practice by fencers and scholars around the world.[3][4]

Normally, several modes of combat were taught alongside one another, typically unarmed grappling (Kampfringen or abrazare), dagger (Degen or daga, often of the rondel dagger), long knife (Messer), or Dusack, half- or quarterstaff, pole weapons, longsword (Langesschwert, spada longa, spadone), and combat in plate armour (Harnischfechten or armazare), both on foot and on horseback. Some Fechtbücher have sections on dueling shields (Stechschild), special weapons used only in trial by combat.

Important 15th century German fencing masters include Sigmund Ringeck, Peter von Danzig (see Cod. 44 A 8), Hans Talhoffer and Paulus Kal, all of whom taught the teachings of Liechtenauer. From the late 15th century, there were "brotherhoods" of fencers (Fechtbruderschaften), most notably the Brotherhood of St. Mark (attested 1474) and the Federfechter.[4]

An early Burgundian French treatise is Le jeu de la hache ("The Play of the Axe") of ca. 1400.

The earliest master to write in the Italian language was Fiore dei Liberi, commissioned by the Marquis di Ferrara. Between 1407 and 1410, he documented comprehensive fighting techniques in a treatise entitled Flos Duellatorum covering grappling, dagger, arming sword, longsword, pole-weapons, armoured combat, and mounted combat.[5] The Italian school is continued by Filippo Vadi (1482–1487) and Pietro Monte (1492, Latin with Italian and Spanish terms).

Three early (before George Silver) natively English swordplay texts exist, but are all very obscure and from uncertain dates; they are generally thought to belong to the latter half of the 15th century.

Early modern period

Renaissance

In the 16th century, compendia of older Fechtbücher techniques were produced, some of them printed, notably by Paulus Hector Mair (in the 1540s) and by Joachim Meyer (in the 1570s). The extent of Mair's writing is unmatched by any other German master, and is considered invaluable by contemporary scholars.[6]

In Germany, fencing had developed sportive tendencies during the 16th century. The treatises of Paulus Hector Mair and Joachim Meyer derived from the teachings of the earlier centuries within the Liechtenauer tradition, but with new and distinctive characteristics. The printed fechtbuch of Jacob Sutor (1612) is one of the last in the German tradition.

In Italy, the 16th century was a period of big change. It opened with the two treatises of Bolognese masters Antonio Manciolino and Achille Marozzo, who described a variation of the eclectic knightly arts of the previous century. From sword and buckler to sword and dagger, sword alone to two-handed sword, from polearms to wrestling (though absent in Manciolino), early 16th-century Italian fencing reflected the versatility that a martial artist of the time was supposed to have achieved.[7]

Towards the mid-16th century, however, polearms and companion weapons besides the dagger and the cape gradually began to fade out of treatises. In 1553, Camillo Agrippa was the first to define the prima, seconda, terza, and quarta guards (or hand-positions), which would remain the mainstay of Italian fencing into the next century and beyond.[8] From the late 16th century, Italian rapier fencing attained considerable popularity all over Europe, notably with the treatise by Salvator Fabris (1606).

- Antonio Manciolino (1531, Italian)

- Achille Marozzo (1536, Italian)

- Angelo Viggiani (1551, Italian)

- Camillo Agrippa (1553, Italian)

- Jerónimo Sánchez de Carranza (1569, Spanish)

- Giacomo di Grassi (1570, Italian)

- Giovanni Dall'Agocchie (1572, Italian)

- Henry de Sainct-Didier (1573, French)

- Angelo Viggiani (1575, Italian)

- Frederico Ghisliero (1587, Italian)

- Vincentio Saviolo (1595, Italian)

- Girolamo Cavalcabo (1597, Italian)

- George Silver (1599, English)

Baroque style

During the Baroque period, wrestling fell from favour among the upper classes, being now seen as unrefined and rustic. The fencing styles practice also needed to conform to the new ideals of elegance and harmony.

This ideology was taken to great lengths in Spain in particular, where La Verdadera Destreza "the true art (of swordsmanship)" was now based on Renaissance humanism and scientific principles, contrasting with the traditional "vulgar" approach to fencing inherited from the medieval period. Significant masters of Destreza included Jerónimo Sánchez de Carranza ("the father of Destreza", d. 1600) and Luis Pacheco de Narváez (1600, 1632). Girard Thibault (1630) was a Dutch master influenced by these ideals.

The French school of fencing also moves away from its Italian roots, developing its own terminology, rules and systems of teaching. French masters of the Baroque period include Le Perche du Coudray (1635, 1676, teacher of Cyrano de Bergerac), Besnard (1653, teacher of Descartes), François Dancie (1623) and Philibert de la Touche (1670).

In the 17th century, Italian swordsmanship was dominated by Salvator Fabris, whose De lo schermo overo scienza d'arme of 1606 exerted great influence not only in Italy, but also in Germany, where it all but extinguished the native German traditions of fencing. Fabris was followed by Italian masters such as Nicoletto Giganti (1606), Ridolfo Capo Ferro (1610), Francesco Alfieri (1640), Francesco Antonio Marcelli (1686) and Bondi' di Mazo (1696).

The Elizabethan and Jacobean eras produce English fencing writers, such as the Gentleman George Silver (1599) and the professional fencing master Joseph Swetnam (1617). The English verb to fence is first attested in Shakespeare's Merry Wives of Windsor (1597).

The French school of fencing originated in the 16th century, which is based on the Italian school, and developed into its classical form during the Baroque period.

Rococo style

In the 18th century, during the late Baroque and Rococo period, the French style of fencing with the small sword and later with the foil (fleuret), originated as a training weapon for small sword fencing.

By 1715, the rapier had been largely replaced by the lighter and handier small sword throughout most of Europe, although treatments of the former continued to be included by authors such as Donald McBane (1728), P. J. F. Girard (1736) and Domenico Angelo (1763).

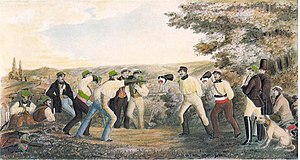

In this time, bare-knuckle boxing emerged as a popular sport in England and Ireland. The foremost pioneers of the sport of boxing were Englishmen James Figg and Jack Broughton.[9]

Throughout the course of the 18th century, the French school became the western European standard to the extent that Angelo, an Italian-born master teaching in England, published his L'Ecole des Armes in French in 1763. It was extremely successful and became a standard fencing manual over the following 50 years, throughout the Napoleonic period. Angelo's text was so influential that it was chosen to be included under the heading of "Éscrime" in the Encyclopédie of Diderot.

Late modern period

Development into modern sports

In the 19th century, Western martial arts became divided into modern sports on one-handed fencing and applications that retain military significance on the other. In the latter category are the methods of close-quarter combat with the bayonet, besides use of the sabre and the lance by cavalrists and of the cutlass by naval forces. The English longbow is another European weapon that is still used in the sport of archery.

Apart from the many styles of fencing, European combat sports of the 19th century include Boxing in England, Savate in France, and regional forms of wrestling such as Cumberland and Westmorland Wrestling, Lancashire Wrestling, and Cornish Wrestling.

Fencing in the 19th century transformed into a pure sport. While duels remained common among members of the aristocratic classes, they became increasingly frowned upon in society during the course of the century, and such duels as were fought to the death were increasingly fought with pistols, instead of bladed weapons.

Stick fighting

Styles of stick fighting include walking-stick fighting (including Irish bata or shillelagh, French la canne and English singlestick) and Bartitsu (an early hybrid of Eastern and Western schools popularized at the turn of the 20th century).

Some existing forms of European stick fighting can be traced to direct teacher-student lineages from the 19th century. Notable examples include the methods of Scottish and British Armed Services singlestick, la canne and Bâton français, Portuguese Jogo do Pau, Italian Paranza or Bastone Siciliano, and some styles of Canarian Juego del Palo.

In the 19th century and early 20th century, the greatstick (pau/bâton/bastone) was employed by some Portuguese, French, and Italian military academies as a method of exercise, recreation, and as preparation for bayonet training.

A third category might be traditional "folk styles", mostly folk wrestling. Greco-Roman wrestling was a discipline at the first modern Olympic Games in 1896. Inclusion of Freestyle wrestling followed in 1904.

19th century revival

Attempts at reconstructing the discontinued traditions of European systems of combat began in the late 19th century, with a revival of interest from the Middle Ages. The movement was led in England by the soldier, writer, antiquarian, and swordsman, Alfred Hutton.

Hutton learned fencing at the school[10] founded by Domenico Angelo. In 1862, he organized in his regiment stationed in India the Cameron Fencing Club, for which he prepared his first work, a 12-page booklet entitled Swordsmanship.[11]

After returning home from India in 1865, Hutton focused on the study and revival of older fencing systems and schools. He began tutoring groups of students in the art of 'ancient swordplay' at a club attached to the London Rifle Brigade School of Arms in the 1880s. In 1889, Hutton published his most influential work Cold Steel: A Practical Treatise on the Sabre, which presented the historical method of military sabre use on foot, combining the 18th century English backsword with the modern Italian duelling sabre.

Hutton's pioneering advocacy and practice of historical fencing included reconstructions of the fencing systems of several historical masters including George Silver and Achille Marozzo. He delivered numerous practical demonstrations with his colleague Egerton Castle of these systems during the 1890s, both in order to benefit various military charities and to encourage patronage of the contemporary methods of competitive fencing. Exhibitions were held at the Bath Club and a fund-raising event was arranged at Guy's Hospital.

Among his many acolytes were Egerton Castle, Captain Carl Thimm, Colonel Cyril Matthey, Captain Percy Rolt, Captain Ernest George Stenson Cooke, Captain Frank Herbert Whittow, Esme Beringer, Sir Frederick, and Walter Herries Pollock.[12] Despite this revival and the interest that was received in late Victorian England, the practice died out soon after the death of Hutton in 1910. Interest in the physical application of historical fencing techniques remained largely dormant during the first half of the 20th century, due to a number of factors.

Similar work, although more academic than practical in nature, occurred in other European countries. In Germany, Karl Wassmannsdorf conducted research on the German school and Gustav Hergsell reprinted three of Hans Talhoffer's manuals. In France, there was the work of the Academie D'Armes circa 1880–1914. In Italy, Jacopo Gelli and Francesco Novati published a facsimile of the "Flos Duellatorum" of Fiore dei Liberi, and Giuseppe Cerri's book on the Bastone drew inspiration from the two-handed sword of Achille Marozzo. Baron Leguina's bibliography of Spanish swordsmanship is still a standard reference today.

20th century

Starting in 1966, the Society for Creative Anachronism, an amateur medieval reenactment organization, renewed public interest in the practice of historic fighting arts,[13] and has hosted numerous tournaments in which participants compete in simulated medieval and renaissance fighting styles using padded weapons.[14][15] Dividing their focus between Heavy Armored Fighting, to simulate early medieval warfare, and adapted sport Rapier fencing, to reenact later renaissance styles, the SCA regularly holds large re-creation scenarios throughout the world. Their styles have been criticized by other groups as lacking historical authenticity, although a number of members of the group regularly engage in scholarship.[16][17]

A number of researchers, principally academics with access to some of the sources, continued exploring the field of historical European martial arts from a largely academic perspective. In 1972, James Jackson published a book called Three Elizabethan Manuals of Fence. This work reprinted the works of George Silver, Giacomo di Grassi, and Vincentio Saviolo. In 1965, Martin Wierschin published a bibliography of German fencing manuals, along with a transcription of Codex Ringeck and a glossary of terms. In turn, this led to the publication of Hans-Peter Hils' seminal work on Johannes Liechtenauer in 1985.

During the mid-20th century, a small number of professional fight directors for theatre, film and television - notably including Arthur Wise. William Hobbs and John Waller, all of them British - studied historical combat treatises as inspiration for their fight choreography.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Patri J. Pugliese began making photocopies of historical treatises available to interested parties, greatly spurring on research. In 1994, with the rise of the Hammerterz Forum, a publication devoted entirely to the history of swordsmanship. During the late 1990s, translations and interpretations of historical sources began appearing in print as well as online.

The modern HEMA community

Since the 1980s and 1990s,[20] historical European martial arts communities have emerged in Europe, North America, Australia, and the wider English-speaking world. These groups attempt to reconstruct historical European martial arts using various training methods. Although the focus generally is on the martial arts of Medieval and Renaissance masters, 19th and early 20th century martial arts teachers are also studied and their systems are reconstructed, including Edward William Barton-Wright, the founder of Bartitsu;[21] combat savate and stick fighting master Pierre Vigny; London-based boxer and fencer Rowland George Allanson-Winn; French journalist and self-defence enthusiast Jean Joseph-Renaud; and British quarterstaff expert Thomas McCarthy.

Research and publications

Research into the rapier style of the innovative Roman, Neapolitan and Sicilian School of Fencing in Italy's 16th and 17th century was pioneered by M° Francesco Lodà, PhD, founder of Accademia Romana d'Armi in Rome, Italy. While research focused on the Marcelli family of fencing masters and their pupils in Rome and abroad (e.g. Mattei, Villardita, Marescalchi, De Greszy, Terracusa), through publication of papers and books on rapier fencing, attention was also paid to the influences of 16th century's masters active in Rome, such as Agrippa, Cavalcabò, Paternoster, or of the early 17th like D'Alessandri. Within Accademia Romana d'Armi historical research has continuously been carried out also on Fiore de' Liberi's longsword system, publishing the first Italian analysis and transcription of MS. Par. Lat. 11269,[22] Radaelli's military saber and MS. I.33 sword and buckler, and more recently on Liechtenauer's tradition of fencing.

Research into Italian sword forms and their influence on the French styles of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries has been undertaken by Rob Runacres of England's Renaissance Sword Club.[year needed]

Italian traditions are mainly investigated in Italy by Sala d'Arme Achille Marozzo, where you can find studies dedicated to the Bolognese tradition, to the Italian medieval tradition by Luca Cesari and Marco Rubboli, and to the Florentine tradition by Alessandro Battistini. Central and Southern Italian traditions are also investigated by Accademia Romana d'Armi, through the studies of Francesco Lodà on Spetioli (Marche) and Pagano (Neaples). Italian rapier instructors Tom Leoni (US) and Piermarco Terminiello (UK) have published annotated English translations of some of the most important rapier treatises of the 17th century, making this fencing style available to a worldwide audience. Leoni has also authored English translations of all of Fiore de' Liberi's Italian-language manuscripts, as well as Manciolino's Opera Nova and the third book of Viggiani's Lo Schermo. Ken Mondschein, one of the few professional academics working in this field, translated Camillo Agrippa's treatise of 1553 as well as the Paris manuscript of Fiore dei Liberi and written several academic articles.

The martial traditions of the Netherlands are researched by Reinier van Noort,[23] who additionally focuses on German and French martial sources of the 17th century.

The ongoing study of the Germanic Langes Messer is most notably represented by the work of Jens Peter Kleinau and Martin Enzi. Dierk Hagedorn has also published significant translations.

Leading researchers on Manuscript I.33's style of fence include Roland Warzecha, at the head of the Dimicator fencing school in Germany.

Other fencing traditions are represented in the scholarship of Stephen Hand and Paul Wagner of Australia's Stoccata School of Defence,[year needed] focusing on a range of systems, ranging from the works of George Silver and the techniques depicted in the Royal Armouries' Manuscript I.33 to the surviving evidence for how large shields were used, rapier according to Saviolo and Swetnam and Scottish Highland broadsword.[24][25][26][27][28]

Christian Henry Tobler is one of the earliest researchers on the German school of swordsmanship.[citation needed]

Early publications also included books by Terry Brown, John Clements, David M. Cvet (self-published in 2001). In 2003, Stephen Hand edited a collection of scholarly papers titled SPADA, followed by a second volume in 2005. Since the mid-2000s, the rate of publication of HEMA related texts has greatly increased. A list of current publications is included below.

Events

Since 1998, Sala d'Arme Achille Marozzo[29] has organized an annual championship in Italy. Due to the excessive number of participants, in 2011 this competitive event was split in two separate events: military weapons (in autumn) and civil weapons (in spring), extending the organization in a larger coalition of Italian HEMA clubs. Civilian weapons include single sword, sword and cape, sword and dagger, and sword and Brocchiero (Buckler). The military weapons are the two-handed sword, spear, shield and spear, sword and targe, and sword and rotella. The civil weapons championship is one of the largest HEMA tournaments in the world.[30]

Since 1999, a number of HEMA groups have held the Western Martial arts Workshop (WMAW) in the United States.[31] In 2000, The Association for Renaissance Martial Arts (ARMA), then known as the "Historical Armed Combat Association" (HACA), hosted the Inaugural Swordplay Symposium International conference bringing together many of the then leading researchers from the US, Europe and Australia. Since 2003, ARMA has held the ARMA International Gathering every two to three years. The Fiore-oriented Schola Saint George has hosted a Medieval Swordsmanship Symposium annually in the United States since 2001.

The annual Australian Historical Swordplay Convention, primarily a teaching event was hosted and attended by diverse Australian groups from 1999 to 2006. It was held in Brisbane in 1999 and 2006, Sydney in 2000 and 2004, Canberra in 2001 and 2005, the Gold Coast in 2003 and Melbourne in 2004. Since 2009, Swordplay, a tournament event has been run each year in Brisbane.

Since 2002, Royal Arts Fencing Academy and the Rose & Gold foundation have hosted Ascalon Sword Festival, one of the largest HEMA tournaments in the United States. The event covers Olympic fencing, as well as the HEMA disciplines of longsword, rapier and dagger, military saber, and Harnisfechten. It was originally part of the larger Arnold Sports Festival as the Arnold Fencing Classic.[32][33]

Since 2004, FightCamp has been running and it is organized by London-based Schola Gladiatoria.[34]

Since 2006, a Swedish annual event called Swordfish has been taking place every year in Gothenburg, hosted by the Gothenburg Historical Fencing School (GHFS). It is currently one of the biggest HEMA tournaments in the world and is generally considered to be the "world cup of HEMA".[35][36]

Since 2006, a Canadian event called Nordschlag has been taking place annually in Edmonton, Alberta, hosted by The Academy of European Swordsmanship (The AES). It is Canada's first interprovincial tournament, and currently largest Canadian tournament, and has participants from all over Western Canada. The event also includes a full day workshop that features international and local instructors.

Since 2010, The annual Pacific Northwest HEMA Gathering[37] has been hosted by multiple schools and clubs in the Pacific Northwest. The tournament includes longsword, singlestick, glima, and one rotating weapon which is changed every year. The location of the event changes every year, and has been located at Fort Casey and Pacific Lutheran University.

Since 2011, a biannual event called the Vancouver International Swordplay Symposium, has been held in Vancouver, Canada. Hosted by Academie Duello, this event has brought instructors, authors and researchers from around the world for workshops, lectures and seminars.

Since 2012, the annual event SoCal Sword Fight has been hosted in Southern California. The event includes tournaments and classes in a variety of historical weapons, including some non-european weapons. In February of 2023, the event had 329 registered fighters and over 500 participants.[38][39]

Since 2013, an annual event, Fechtschule Edinburgh, an event focusing on 16th century Fencing has been hosted in Edinburgh, UK, by the Stork's Beak: School of Historical Swordplay. This Event has attracted many practitioners from around the world.[40]

Since 2014, the Purpleheart Armoury Open has been held in Houston, TX. Formerly Fechtshule America, the Purpleheart Armoury Open is one of the largest and fastest growing HEMA competitions in North America.

In 2015, Australia's Stoccata School of Defence hosted a revival of the World Broadsword Championship in Sydney, Australia. This event, held throughout the late 19th century in England, the United States and Australia was last won by Parker in Sydney in 1891. Parker was never challenged. The 2015 event was won by Paul Wagner of Sydney, also the current holder of the Glorianna Cup, the broadsword championship of Britain. Lewis Hand of Hobart, Australia won the junior title. In the tradition of the 19th century title, the championship is held in the home town of the current Champion. As such the next championship will be held in Sydney in early 2017.

Jousting tournaments have become more common, with Jousters travelling Internationally to compete. These include a number organised by an expert in the Joust, Arne Koets, including The Grand Tournament of Sankt Wendel and The Grand Tournament at Schaffhausen[41]

Another type of event that is becoming more common is the sparring camp/fight camp. These events are often more casual than tournaments, with events and competitions not typical of more formal tournaments, and an emphasis on classes and sparring.[42][43]

Umbrella groups

In 1998, the British Federation for Historical Swordplay was established as an umbrella organisation for UK groups.

In 2001, the Historical European Martial Arts Coalition (HEMAC) was created to act as an umbrella organization for groups in Europe, with 4 sets of goals:

- Martial

- reconstruct historical martial arts from primary sources; refine interpretations into viable, effective martial arts; test martial skills in a variety of competitive environments

- Research

- locate, transcribe, translate primary sources; have a better understanding of the socio-historical context of the arts

- Outreach

- promote and publicise HEMA; dispel misconceptions & stereotypes; educate the general public

- Community

- establish a network of individuals and groups devoted to HEMA; foster close friendships and a sense of community among members; organise at least one annual HEMAC event.[44] Since 2002, HEMAC has organized the annual International Historical European Martial arts Gathering in Dijon, France.[45]

In 2003, the Australian Historical Swordplay Federation became the umbrella organization for groups in Australia.

In 2010, several dozen HEMA schools and clubs from around the world united under the umbrella of the HEMA Alliance, a US-based martial arts federation dedicated to developing and sharing the Historical European Martial Arts and assisting HEMA schools and instructors with such things as instructor certification, insurance, and equipment development.[46]

In 2012, Ruth García Navarro and Mariana López Rodríguez started Esfinges, an umbrella affinity group for women in or interested in HEMA. The goal of Esfinges is to encourage more participation of underrepresented genders in HEMA, and to support those already practicing the discipline.[47]

See also

- Arne Koets

- Historical European Martial Arts in Australia

- Combat reenactment

- English Longsword School

- Fencing

- French school of fencing

- German school of swordsmanship

- Italian school of swordsmanship

- Laurentius Guild

- Martial arts manual

- Spanish school of swordsmanship

- Renaissance Sword Club

- Schola Gladiatoria

- Swordsmanship

- Waster

- History of physical training and fitness

References

- ^ Epitoma rei militaris. Oxford Classical Texts. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. 6 May 2004. ISBN 978-0-19-926464-3.

- ^ between ca. 1290 (by Alphonse Lhotsky[year needed]) and the early-to-mid-14th century (by R. Leng, of the University of Würzburg[year needed])

- ^ Hagedorn, Dierk (2021). Renaissance combat : Jörg Wilhalm's fightbook, 1522-1523. Helen Hagedorn, Henri Hagedorn, Tobias Capwell. South Yorkshire. ISBN 978-1-78438-657-3. OCLC 1257553499.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Staff, HEMA Resources (29 July 2020). "The Liechtenauer tradition and the German school of fencing in HEMA". HEMA-Historical European Martial Arts. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Howe, Russ (2008). "Fiore dei Liberi: Origins and Motivations". Journal of Western Martial Art. 1 (3) – via SPORTDiscus with Full Text.

- ^ ARMA. "Paulus Hector Mair". The Association for Renaissance Martial Arts. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ Tom Leoni, The Complete Renaissance Swordsman, Freelance Academy Press, 2010

- ^ Tom Leoni, Venetian Rapier, Freelance Academy Press, 2010

- ^ Roberts, Randy (1977). "Eighteenth Century Boxing". Journal of Sport History. 4 (3): 248–250. JSTOR 43610520.

- ^ Sieveking, A. F. (2004). "Alfred Hutton". In Lock, Julian (ed.). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 1 (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34078. Retrieved 10 July 2015. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "SCHOLA FORUM". Fioredeiliberi.org. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ Thimm, Carl Albert (1896). A Complete Bibliography of Fencing and Duelling. London. ISBN 9781455602773. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Cramer, Michael A. (2009). Medieval Fantasy as Performance: The Society for Creative Anachronism and the Current Middle Ages, Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810869967.

- ^ Martial Activities, Society for Creative Anachronism. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ Price, Brian R. (2010). The Book of the Tournament, 2nd Edition, Chivalry Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-891448-00-3.

- ^ Mondschein, Ken (2011). The Knightly Art of Battle, J. Paul Getty Museum, ISBN 978-1606060766.

- ^ Price, Brian A. (2005). Teaching & Interpreting Historical Swordsmanship, Chivalry Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-891448-46-1.

- ^ "About us - Sigi Forge". sigiforge.com. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ "About Us". www.woodenswords.com. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ About Us. Fightcamp Events. (n.d.). https://fightcampevents.com/hema/#:~:text=Historical%20European%20Martial%20Arts%20involve,unearthed%20old%20manuscripts%20and%20manuals.

- ^ "Bartitsu". Fullcontactmartialarts.org. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ Lodà, Francesco (2014). Florius. De Arte Luctandi. Bonanno. ISBN 978-8896950869.

- ^ Reinier van Noort. "Publications - The School for Historical Fencing Arts". Bruchius.com. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ Hand, Stephen (2006). English Swordsmanship. Highland Village: Chivalry Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-891448-27-0.

- ^ Hand, Stephen (2003). Spada. San Francisco: Chivalry Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-891448-37-9.

- ^ Hand, Stephen (2005). Spada II. San Francisco: Chivalry Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-891448-35-5.

- ^ Wagner and Hand (2004). Medieval Sword and Shield. San Francisco: Chivalry Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-891448-43-0.

- ^ Wagner, Paul (2008). Master of Defence: The Works of George Silver. Paladin Press. ISBN 978-1581607239.

- ^ "Sala d'Arme Achille Marozzo - Associazione culturale e sportiva". Achillemarozzo.it. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ "2014 – VI° Torneo Nazionale di Scherma Antica UISP – Discipline Civili". Achillemarozzo.it. 7 August 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ Gregory Mele, ed., In the Service of Mars: Proceedings from the Western Martial Arts Workshop 1999–2009, Volume I, Freelance Academy Press, 2010

- ^ Goldsmith, Suzanne. "Arnold Fencing Classic Rebrands as Ascalon Sword Festival". Columbus Monthly. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Ascalon Sword Festival | Royal Arts Fencing". Ascalon Sword Festival. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "FightCamp". Fioredeiliberi.org. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ "Hem". Ghfs.se. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ "What is this about?". kickstarter.com.

- ^ "Pacific Northwest HEMA Gathering". pnwhemag.com/. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ "HEMA Scorecard". hemascorecard.com. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ "About SoCal Swordfight". SoCal Swordfight. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ "Stork's Beak: School of Historical Swordsmanship". www.storksbeak.co.uk.

- ^ "An Interview with Arne Koets, jouster" The Jousting Life, December 2014

- ^ "Funfecht 2022". Eventbrite. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Harvest Fecht 4". Queen City Sword Guild. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "HEMAC". hemac.org.

- ^ "» HEMAC-Dijon". Hemac-dijon.com. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ "About The HEMA Alliance". Hemaalliance.com. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ "Esfinges – HEMA". Retrieved 11 November 2022.

Further reading

This "Further reading" section may need cleanup. (May 2017) |

- Angelo, Domenico, The School of Fencing: With a General Explanation of the Principal Attitudes and Positions Peculiar to the Art, eds. Jared Kirby, Greenhill Books, 2005. ISBN 978-1853676260

- Anglo, Sydney. The Martial Arts of Renaissance Europe. Yale University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-300-08352-1

- Blanes, Jerome. Nicolaes Petter, the Biography. Lulu.com, 2014. ISBN 978-1105916694

- Brown, Terry. English Martial Arts. Anglo-Saxon Books, 1997. ISBN 1-898281-29-7

- Butera, Matteo, Francesco Lanza, Jherek Swanger, and Reinier van Noort. The Spada Maestra of Bondì di Mazo. Van Noort, Reinier, 2016. ISBN 978-82-690382-0-0

- Clements, John. Medieval Swordsmanship: Illustrated Methods and Techniques. Paladin Press, 1998. ISBN 1-58160-004-6

- Clements, John. Renaissance Swordsmanship: The Illustrated Book of Rapiers and Cut-and-Thrust Swords and Their Use. Paladin Press, 1997. ISBN 0-87364-919-2

- Clements, John et al. Masters of Medieval and Renaissance Martial Arts: Rediscovering The Western Combat Heritage. Paladin Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1-58160-668-3

- Forgeng, Jeffrey L. The Art of Combat: A German Martial Arts Treatise of 1570. Frontline Books, 2014. ISBN 978-1848327788.

- Gaugler, William. The History of Fencing: Foundations of Modern European Fencing. Laureate Press, 1997. ISBN 1-884528-16-3

- Hand, Stephen. SPADA: An Anthology of Swordsmanship in Memory of Ewart Oakeshott. Chivalry Bookshelf, 2003. ISBN 1-891448-37-4

- Hand, Stephen. SPADA 2: Anthology of Swordsmanship. Chivalry Bookshelf, 2005. ISBN 1-891448-35-8

- Hand, Stephen. English Swordsmanship: The True Fight of George Silver, Vol. 1: Single Sword. Chivalry Bookshelf,2006. ISBN 1-891448-27-7

- Heim, Hans and Alex Kiermayer. The Longsword of Johannes Liechtenauer, Part I (DVD). Agilitas TV, 2005. ISBN 1-891448-20-X

- Kirby, Jared (ed.), Italian Rapier Combat - Ridolfo Capo Ferro, Greenhill Books, London, 2004. ISBN 1853675806

- Kirby, Jared (ed.), A Gentleman's Guide to Duelling: Of Honour and Honourable Quarrels. Frontline Books, 2014. ISBN 1848325274

- Knight, David James and Brian Hunt. Polearms of Paulus Hector Mair. Paladin Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1-58160-644-7

- Leoni, Tommaso. The Art of Dueling. The Chivalry Bookshelf, 2005. ISBN 1-891448-23-4

- Leoni, Tom. Venetian Rapier. Freelance Academy Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-9825911-2-3

- Leoni, Tom. The Complete Renaissance Swordsman. Freelance Academy Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-9825911-3-0

- Lindholm, David and Peter Svärd. Sigmund Ringeck's Knightly Art of the Longsword. Paladin Press, 2003. ISBN 1-58160-410-6

- Lindholm, David and Peter Svärd. Knightly Arts of Combat - Sigmund Ringeck's Sword and Buckler Fighting, Wrestling, and Fighting in Armor. Paladin Press, 2006. ISBN 1-58160-499-8

- Lindholm, David. Fighting with the Quarterstaff. The Chivalry Bookshelf, 2006. ISBN 1-891448-36-6

- Mele, Gregory, ed. In the Service of Mars: Proceedings from the Western Martial Arts Workshop 1999–2009, Volume I. Freelance Academy Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-9825911-5-4

- Price, Brian R., ed. Teaching & Interpreting Historical Swordsmanship. The Chivalry Bookshelf, 2005. ISBN 1-891448-46-3

- Runacres, Rob. Treatise or Instruction for Fencing, Lulu.com (2015), ISBN 978-1-326-16469-0

- Runacres, Rob and Thibault Ghesquiere. The Sword of Combat or The Use of Fighting With Weapons. Lulu.com, 2014. ISBN 978-1-29191-969-1

- Runacres, Rob. Book of Lessons. Fallen Rook, 2017. ISBN 978-0-9934216-5-5

- Thompson, Christopher. Lannaireachd: Gaelic Swordsmanship. BookSurge Publishing, 2001. ISBN 1-59109-236-1

- Tobler, Christian Henry. Secrets of German Medieval Swordsmanship. The Chilvarly Bookshelf, 2001. ISBN 1-891448-07-2

- Tobler, Christian Henry. Fighting with the German Longsword. The Chivalry Bookshelf, 2004. ISBN 1-891448-24-2

- Vail, Jason. Medieval and Renaissance Dagger Combat. Paladin Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1-58160-517-4

- Van Noort, Reinier. Lessons on the thrust. Fallen Rook Publishing, 2014, ISBN 978-0-9926735-4-3

- Van Noort, Reinier. Of the Single Rapier. Fallen Rook Publishing, 2015, ISBN 978-0-9926735-8-1

- Van Noort, Reinier. Swordplay: an anonymous illustrated Dutch treatise for fencing with rapier, sword and polearms from 1595. Freelance Academy Press, 2015, ISBN 978-1-937439-26-2

- Van Noort, Reinier and Antoine Coudre. True Principles of the Single Sword. Fallen Rook Publishing, 2016, ISBN 978-0-9934216-0-0

- Wagner, Paul. Master Of Defence: The Works of George Silver. Paladin Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1581607239

- Wagner, Paul and Stephen Hand. Medieval Sword and Shield: The Combat System of Royal Armouries MS. I.33. Chivalry Bookshelf, 2004. ISBN 1-891448-43-9

- Windsor, Guy. The Swordsman's Companion: A Modern Training Manual for Medieval Longsword. The Chivalry Bookshelf, 2004. ISBN 1-891448-41-2

- Zabinski, Grzegorz and Bartlomiej Walczak. The Codex Wallerstein: A Medieval Fighting Book from the Fifteenth Century on the Longsword, Falchion, Dagger, and Wrestling. Paladin Press, 2002. ISBN 1-58160-339-8

External links

- Acta Periodica Duellatorum Archived 27 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, a peer-reviewed journal of historical European martial arts research

- Meyer Freifechter Guild, International Fencing Guild with a mission to educate people on the efficacy and art of Medieval & Renaissance martial arts.

- A Chronological History of the Martial arts and Combative Sports 1350–1699 by Joseph R. Svinth

- Historical European Martial Arts: Studies & Sources. On-line historical and literary magazine for Russian speaking and partly for English speaking readers.

- HROARR, an online repository of articles and other resources on historical European martial arts and sports

- Wiktenauer, the world's largest library of historical European martial arts treatises, currently complete up to the late 1500s

- AEMMA - Academy of European Medieval Martial Arts

- Official website of HEMA ITALIA - Societas Artis Gladii - Information Point of Italian Martial Arts

- Academy of Medieval Fencing and Culture - HEMA in Russia

- Fencing club "NoName" - HEMA in Russia