Tampa Stadium

"The Big Sombrero" | |

Tampa (Houlihan's) Stadium in early 1999 | |

| |

| Full name | Tampa Stadium |

|---|---|

| Former names | Tampa Stadium (November 4, 1967 – December 28, 1995) Houlihan's Stadium (January 16, 1996 – April 11, 1999) |

| Address | 4201 N Dale Mabry Hwy |

| Location | Tampa, Florida |

| Coordinates | 27°58′44″N 82°30′13″W / 27.97889°N 82.50361°W |

| Owner | Tampa Sports Authority |

| Operator | Tampa Sports Authority |

| Capacity | 46,481 (original) 74,301 (final) |

| Surface | Bermuda grass |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | October 9, 1966 |

| Opened | November 4, 1967 |

| Renovated | 1983, 1990 |

| Expanded | December 4, 1974 – June 5, 1975 |

| Closed | September 13, 1998 |

| Demolished | April 11, 1999 |

| Construction cost | US$4.4 million ($40.2 million in 2023 dollars[1]) US$13 million (renovations) ($39.8 million in 2023 dollars[1]) |

| Architect | Watson & Company Architects, Engineers & Planners |

| General contractor | Jones-Mahoney Construction Co.[2] |

| Tenants | |

| Tampa Spartans (NCAA) (1967–1974) Tampa Bay Rowdies (NASL / independent / ASL / APSL) (1975–1986, 1988–1990, 1993) Tampa Bay Buccaneers (NFL) (1976–1997) Tampa Bay Bandits (USFL) (1983–1985) Outback Bowl (NCAA) (1986–1998) Tampa Bay Mutiny (MLS) (1996–1998) South Florida Bulls (NCAA) (1997) | |

Tampa Stadium (nicknamed The Big Sombrero and briefly known as Houlihan's Stadium) was a large open-air stadium (maximum capacity about 74,000) located in Tampa, Florida, which opened in 1967 and was significantly expanded in 1974–75. The facility is most closely associated with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers of the National Football League, who played there from their establishment in 1976 until 1997. It also hosted two Super Bowls, in 1984 and 1991, as well as the 1984 USFL Championship Game. To meet the revenue demands of the Buccaneers' new owners, Raymond James Stadium was built nearby in 1998, and Tampa Stadium was demolished in early 1999.

Besides the Bucs, Tampa Stadium was home to the Tampa Bay Rowdies of the original North American Soccer League, the Tampa Bay Bandits of the United States Football League, the Tampa Bay Mutiny of Major League Soccer, and the college football programs of the University of Tampa and the University of South Florida. It also hosted many large concerts, and for a time, it held the record for the largest audience to ever see a single artist when a crowd of almost 57,000 witnessed a Led Zeppelin show in the facility in 1973.

Origin and design

Pre-history and construction

The land on which Tampa Stadium was situated had been the perimeter of Drew Field, a World War II-era airfield which was the precursor to Tampa International Airport. In 1949, the city of Tampa bought a 720-acre (290 ha) grassy parcel between the airport and West Tampa from the federal government with the idea of eventually building a community sports complex.[3][4] Al Lopez Field was the first phase of the project, opening in 1955. However, further development stalled for several years after that.

Though the city of Tampa already had a long history with amateur and minor league professional sports and had undergone tremendous growth after World War 2, it did not yet have a modern football stadium as the 1960s began. The two largest extant venues were both located across the Hillsborough River from downtown: Plant Field, which had been built in the 1890s and consisted of a single grandstand and a large open field, and Phillips Field, which had been built in the 1930s as the home of the University of Tampa's football team. Some of Tampa's civic leaders began to discuss plans for attracting an expansion or relocated professional football franchise to the area by the early 1960s and arranged an exhibition game between the American Football League's Buffalo Bills and New York Jets at Phillips Field on August 8, 1964. Though temporary bleachers were installed to increase capacity to 17,000, actual attendance was less than 6000.[5] Realizing that the venue was too small and primitive to support a professional football franchise, the city decided to construct a large modern football facility which could be used by the Tampa Spartans in the short term and could be expanded to serve as the home field for an NFL or AFL franchise in the future.[6]

Construction of Tampa Stadium began in the fall of 1966 just beyond the left field wall of Al Lopez Field, which was by then the home of the Tampa Tarpons of the Florida State League and the spring training home of the Cincinnati Reds. The plot purchased by the city in 1949 was large enough to host separate football and baseball venues, training facilities for the Reds, and several acres of parking spaces.[7]

Original design

When it opened in 1967, Tampa Stadium consisted of a matching pair of large arch-shaped concrete grandstands with open endzones. The seating consisted of long, backless aluminum benches that were accessed via short tunnels (vomitoria) which connected the seating area to wide, open concourses at the rear of the grandstands. The benches were arranged in two large tiers divided by a horizontal walkway about halfway up the grandstands. The slope of the grandstands was relatively steep, giving every seat a direct and unobstructed view of the field. The official capacity was 46,481, though temporary bleachers could be placed in one or both endzones if needed.[8]

Expansions and renovations

| Years | Official capacity |

|---|---|

| 1967–1975 | 46,481[8] |

| 1976–1978 | 71,951[8] |

| 1979–1981 | 72,126[9] |

| 1982–1984 | 72,812[10] |

| 1985–1988 | 74,315[11] |

| 1989–1992 | 74,296[12] |

| 1993–1998 | 74,301[13] |

Tampa Stadium underwent an extensive expansion project in 1974–1975 after the city was awarded an NFL expansion team. Over 27,000 seats were added by completely enclosing the open end zones with seating areas that blended into the existing two-tiered grandstands and created two walkways that completely encircled the seating bowl at ground level and about 40 rows up. The finished stadium had the largest capacity in the NFL (71,908)[14] and was not in the shape of a simple bowl. The top of the stadium was in the shape of a wave which was highest at the center of the two sideline grandstands and gently sloped downward to a rounded corner where it met the endzone sections, which were a little more than half as tall. Much later, the stadium was dubbed "The Big Sombrero" by ESPN's Chris Berman for the unique undulating hat / wave shape created by the 1975 expansion.

The last major renovation took place in the early 1980s when, in preparation for its first Super Bowl in January 1984, the press box atop the west grandstand was expanded and updated and a large new suite of luxury boxes was added atop the east grandstand. This configuration gave the facility its maximum seating capacity of 74,301.

For the 1990 season which culminated in the stadium's second Super Bowl, large flagpoles were mounted on the upper rim of the stadium as part of a stadium update that included the addition of a JumboTron screen in the south end zone and smaller scoreboards above the field-level tunnels in two corners of the stadium. The poles were used to fly large flags for each of the NFL's teams until 1997, when the Buccaneers adopted a uniform redesign featuring a red flag on their helmets. Large versions of the flag were hoisted on the stadium's flagpoles when the Buccaneers penetrated their opponents' 20-yard line. The franchise continued this practice when it moved to Raymond James Stadium next door a year later.

Playing surface

Over the lifetime of Tampa Stadium, the natural grass turf consisted of several varieties of Bermuda grass, most notably Tifway 419. The playing surface was consistently one of the best in the NFL, and was regularly named a players' favorite in surveys conducted by the National Football League Players Association.[15][16][17]

Heat

Tampa Stadium was built almost exclusively of concrete. Throughout its existence, exterior walls were painted light tan or white or left as bare concrete, as were the flooring surfaces. Seating consisted of long aluminum benches, and there was no roof or overhang of any kind over the field or seating areas.

While the stadium's minimalist design allowed for very good sight lines, it also exposed both spectators and players to the full brunt of Tampa's subtropical climate. This was especially true after the stadium was fully enclosed for the Buccaneers' 1976 inaugural season, cutting off breezes which had flowed through the open endzones.[18] While fans could retreat under the grandstands to the shade of the wide concourses where concessions and restrooms were located, players and personnel on the field had no such recourse. Cooling equipment was usually placed near the sideline benches. The Buccaneers were also allowed to wear their white jerseys at home, forcing their opponents to suffer in their darker (and hotter) jerseys. During the summer and early autumn, events in the stadium were often scheduled in the evening hours to avoid the often oppressive afternoon heat and humidity. In another nod to local weather, the natural grass playing surface was highly crowned to provide rapid drainage during Tampa's intense thunderstorms, with the sidelines almost 18 inches lower than the center of the field.

Sporting history

First tenants

University of Tampa Spartans

Tampa Stadium was completed just in time to host its first sporting event – a football game between the University of Tampa Spartans and the #3 ranked University of Tennessee Volunteers on November 4, 1967.[19] While the Spartans lost that game 38-0, they would enjoy later success in their new home, moving up to Division I football in 1971, defeating several established programs, and sending several players to the NFL, including Freddie Solomon and John Matuszak.[20] However, university officials were unsure of continued community support after Tampa was awarded an NFL expansion franchise. "Tampa U" president B. D. Owens ended the football program after the 1974 season, saying that the school would face bankruptcy if it had to subsidize the sport.[21]

Tampa Bay Rowdies

The Tampa Bay Rowdies were the stadium's first professional tenant, starting play in 1975 and winning their only (outdoor) championship in their inaugural season. (The team also won several indoor soccer championships playing at the Bayfront Center across Tampa Bay in St. Petersburg.)

The Rowdies played their home games in Tampa Stadium every summer until the original North American Soccer League disbanded in 1984. Subsequently, the Rowdies continued on, first as an independent team, then in other leagues (ASL, APSL) and used the stadium every year through 1990. In 1991 and 1992 they moved across town to the smaller USF Soccer Stadium, before returning to Tampa Stadium in 1993 for their final season of play in the APSL.[22][23][24]

NFL expansion

Exhibition games

After the disappointing turnout at Phillips Field for an AFL preseason game back in 1964, the city was eager to showcase its new stadium in the hopes of attracting a professional franchise and organized a dozen exhibition games in Tampa Stadium in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The first of these was a preseason game between the NFL's Atlanta Falcons and Washington Redskins in August 1968 that almost sold out the larger venue, and preseason matchups over subsequent seasons similarly drew large and enthusiastic crowds.[25] In 1972, the Baltimore Colts trained at Leto High School, West of Tampa, in unincorporated Hillsborough County during the preseason and played all three of their exhibition games in Tampa Stadium to large crowds.[26]

These preseason games gave NFL owners and officials ample opportunity to assess the Tampa Bay area and the stadium, and on April 24, 1974, Tampa was awarded an NFL expansion team to begin play in the 1976.[27]

Tampa Bay Buccaneers

The Buccaneers' first regular season home game was held on September 19, 1976, when the Bucs lost to the San Diego Chargers 23-0. That would become a trend, as the team began their existence with an NFL-record 26-game losing streak. They would not win a game on their home field until defeating the St. Louis Cardinals on the last game of the following season, December 18, 1977. Jubilant fans swarmed the Tampa Stadium turf and tore down the goal posts.[28]

The Buccaneers had improved enough by the 1979 season to host the NFC Championship Game, which they lost 9-0 to the Los Angeles Rams. The Bucs played 18 additional seasons in the facility but struggled through most of them. They would only host one more playoff game on their original home turf: an NFC Wild Card Game vs. the Detroit Lions on December 28, 1997, which they won 20-10. This would be the last game the team ever played in Tampa Stadium, as they moved next door to Raymond James Stadium in 1998.

Krewe of Honor

In 1991, the organization initiated the "Krewe of Honor", which featured a mural of the first class of three members.[29] Quarterback Doug Williams was inducted September 6, 1992 and owner Hugh Culverhouse on September 5, 1993. No additional members were added before Tampa Stadium was closed and demolished.

| Tampa Stadium Krewe of Honor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | No. | Name | Position | Tenure |

| 1991 | 63 | Lee Roy Selmon | DE | 1976–1984 |

| — | John McKay | Head Coach | 1976–1984 | |

| 42 | Ricky Bell | RB | 1977–1981 | |

| 1992 | 12 | Doug Williams | QB | 1978–1982 |

| 1993 | — | Hugh Culverhouse | Owner | 1976–1994 |

Houlihan's Stadium

Malcolm Glazer also acquired naming rights to Tampa Stadium when he purchased the Buccaneers in 1995. In October of that year, he had the Houlihan's restaurant chain, another business in his portfolio, pay the Bucs $10 million for those rights. This resulted in the official name of the facility being changed to "Houlihan's Stadium" in 1996 and in Glazer being sued by Houlihan's stockholders, who were not happy about purchasing stadium naming rights in an area in which the chain had no restaurants.[30][31]

Other tenants and events

Tampa Stadium was the home field for several additional teams and hosted a wide variety of events during its lifetime.

Home teams

- From 1983 to 1985, the Tampa Bay Bandits, one of the 12 original USFL franchises, were the stadium's third professional tenant. The Bandits enjoyed strong ticket sales and fan support and were one of only two USFL teams (the Birmingham Stallions being the other) to stay in their original city and stadium and have the same head coach (former Florida Gators and Bucs quarterback Steve Spurrier) for the league's three seasons. However. the Bandits folded along with the USFL after the 1985 season.

- The University of South Florida Bulls football team played its initial season at the stadium in 1997, becoming the stadium's second and final collegiate tenant. The Bulls would play the final football game at the stadium on September 12, 1998, defeating Valparaiso 51-0 before moving to Raymond James Stadium for their next home game on October 3, 1998.

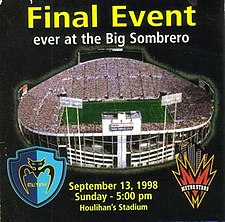

- Major League Soccer placed one of its original teams in Tampa in 1996. The Tampa Bay Mutiny were the stadium's fourth and final professional tenant. The Mutiny used the stadium as their home field for their first three seasons, and moved to Raymond James Stadium in 1999. They hosted the last sporting event at the stadium on September 13, 1998, when they defeated the New York MetroStars 2-1 in front of 27,957 people.[32]

Sporting events

- Tampa Stadium hosted two Super Bowls. Super Bowl XVIII in which the Los Angeles Raiders defeated the Washington Redskins 38–9, took place on January 22, 1984. Super Bowl XXV, in which the New York Giants beat the Buffalo Bills 20–19 in what was the closest Super Bowl game ever, took place on January 27, 1991. Tampa Stadium is one of seven stadiums that had hosted a Super Bowl that are no longer standing (the other six are Tulane Stadium, demolished in 1980; Stanford Stadium, in 2006; the Orange Bowl, in 2008; the Metrodome, in 2014; the Georgia Dome, in 2017, the Pontiac Silverdome, in 2018, and Jack Murphy Stadium in 2021). Subsequent Super Bowls in Tampa have been played at Raymond James Stadium.

- The NFL Pro Bowl was held at Tampa Stadium on January 29, 1978, two years before the game began a 30-year residency in Honolulu, Hawaii.

- Though the University of Florida is approximately 120 miles (190 km) north in Gainesville, a strong local alumni base persuaded the Florida Gators football team to schedule nine regular season games in Tampa Stadium between 1968 and 1989.[33] However, the Gators have not played a regular season contest in Tampa since a 1990 expansion made Florida Field the largest football facility in the state.[34]

- In 1978 and 1979, the stadium hosted the Can-Am Bowl, which was a college all-star game pitting seniors from the United States against seniors from Canada. The contest used the rules of Canadian football, which required that the playing field be enlarged to the specifications of the Canadian game.[35][36][37]

- From 1978 to 1996, Tampa Stadium hosted the Florida Classic rivalry game between the Bethune–Cookman University Wildcats and the Florida A&M Rattlers, two in-state historically black colleges that play in the NCAA's Football Championship Subdivision.

- On July 15, 1984, Tampa Stadium hosted the 2nd USFL Championship Game between the Philadelphia Stars and the Arizona Wranglers.

- From 1986 to 1998, college football's Outback Bowl (previously held in Birmingham, Alabama as the Hall of Fame Bowl) was played in Tampa Stadium on New Year's Day. The 1999 Outback Bowl and all subsequent editions have been played at Raymond James Stadium.

- Tampa Stadium hosted the USHRA monster truck rally Monster Jam in late January or early February (after football season, when turf damage wouldn't matter) for many years.[38] Its replacement venue, Raymond James Stadium continues to host Monster Jam in Tampa to this day.

- Beginning in 1971, Tampa Stadium served as host for the American Invitational show jumping competition each spring, which brought together the USEF's top 30 ranked equestrians to compete for the sport's largest purse. The event is now held in Raymond James Stadium.[39]

Concerts

The stadium hosted concerts by many famous artists, including Deep Purple, The Who, Jethro Tull, Santana, Paul McCartney, David Bowie, U2, The Rolling Stones, Jimmy Buffett, The Eagles, Whitney Houston, Jonathan Butler, Genesis, Kenny G, George Michael, Pink Floyd, the Grateful Dead, and several big acts at the same time during the 1988 Monsters of Rock Tour, among others.

Two particularly memorable concerts were held there by the English rock band Led Zeppelin. On May 5, 1973, the band attracted 56,800 people, which at the time represented the largest audience for a single artist performance in history, breaking the record set by The Beatles at Shea Stadium in 1965.[40] On June 3, 1977, the band returned to the venue, but the concert was paused and ultimately cut short due to a large thunderstorm. The crowd became unruly after the announcement of the cancellation, and the Tampa police ultimately dispersed the "riot" using tear gas and billy clubs.[41] Much criticism was leveled at both the concert organizers' decision to cancel the performance and the aggressive tactics of law enforcement, resulting in a year-long pause of concerts at Tampa Stadium until security protocols were revised and shows were allowed to resume.[42]

Special events

In March 1979, evangelist Billy Graham held a "Florida West Coast Crusade" at Tampa Stadium and drew a combined crowd of about 175,000 over five consecutive days.[43]

Demolition

Immediately upon buying the Buccaneers in 1995, new owner Malcolm Glazer declared that Tampa Stadium was inadequate and threatened to move the franchise to another city unless a new stadium was built at taxpayers' expense.[44][45] To accommodate these demands, Hillsborough County raised local sales taxes and built Raymond James Stadium just south of Tampa Stadium in 1997–98.[46]

Demolition of Tampa Stadium proceeded soon after the Tampa Bay Mutiny's final home game on September 13, 1998.[47] Wrecking balls and long reach excavators were used for much of the process, and the last portion of the stadium (the east side luxury boxes built for the stadium's first Super Bowl), was imploded on April 11, 1999. Tampa Stadium's former site is now a parking and staging area for Raymond James Stadium, and its footprint can still be seen in a grassy area inside a roughly circular road that once ringed its perimeter.

References

- ^ a b 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "Local $ Needed For Stadium". St. Petersburg Times. July 28, 1966. Retrieved March 31, 2012.

- ^ "Tampa in the 1940s page 4". www.tampapix.com.

- ^ "Big Deeds Need Big Plans" St. Pete Times, June 9, 1949

- ^ Bill Kirby, "Only 5,827 See AFL Duel," Tampa Tribune, August 9, 1964, 1-C

- ^ "Tampa football all began at Phillips Field" Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine The Tampa Tribune

- ^ "Tampa Sports Authority".

- ^ a b c "Redskins Regain Beban For Exhibition at Tampa". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. August 4, 1968.

- ^ "Tampa Stadium Sold Out". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. August 10, 1979.

- ^ "Detroit Has a Gay Day at Sacking Tampa Bay". The Palm Beach Post. September 5, 1983.

- ^ David Steele (August 15, 1986). "Bucs' Season-Ticket Sales Dip Sharply". The Evening Independent.

- ^ "Buccaneers". Gainesville Sun. September 26, 1989.

- ^ "Ticket Sales Up With Threat of Bucs Move". The Tuscaloosa News. December 21, 1994.

- ^ Ron Martz (August 19, 1978). "Bucs Return to Scene of First Victory". St. Petersburg Times.

- ^ "Good Footing". buccaneers.com. 4 February 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ^ "Field in Tampa Stadium Draw Raves from Expert". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. 21 January 1984. Retrieved 10 Aug 2016 – via AP.

- ^ "On the Field-A team Update". The Orlando Sentinel. January 29, 1999. p. 28. Retrieved August 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Florida Heat is Tampa Bay's Real Home Field Advantage" St. Pete Times, Aug. 25, 1976

- ^ "D-Day Arrives for Tampa" St. Pete Times, Nov. 4, 1967

- ^ "University of Tampa Spartans used to be the toast of the town". Orlando Sentinel. 2009-01-25. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ "UT Journal – Winter 2007 – ut.edu" (PDF).

- ^ Rusnak, Jeff (1991-06-23). "Strikers Look Bad, But Still Sneak By Rowdies 1-0". Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved 2014-04-15.

- ^ "TAMPA BAY ROWDIES APPRECIATION BLOG (1975 to 1993): Rowdies Memorabilia - 1992 Rowdies Season Ticket Pamphlet". 2010-04-05.

- ^ Brousseau, Dave (1993-06-13). "Eichmann Nets 2 In Striker Victory First Half At Tampa Gets Rowdy". Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved 2014-04-15.

- ^ "Bucpower.Com". Bucpower.Com. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ Wallace, William N. (29 February 1972). "Colts plan workout in Tampa, add fuel to Baltimore story". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ^ "Tampa Bay Proves Its Winning Way". .tbo.com. 2009-01-31. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ Mizell, Hubert. "At last! A Tampa Stadium victory celebration". St. Petersburg Times. 19 Dec 1977

- ^ Werder, Ed (1991-12-05). "Tampa Initiates Krewe Of Honor". Tampa Bay. Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ "Stockholder sue Glazer" St. Pete Times, Dec. 2, 1995

- ^ "Is Zapata the Glazers' Toy?" Bloomberg BusinessWeek, Oct. 7, 1996

- ^ "Major League Soccer: History: Games". Web.mlsnet.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ "52,000 Seen for '68 Debut in Stadium" St. Pete Times, September 21, 1968

- ^ "03_2010_Records&History_pp135-200.indd" (PDF).

- ^ Zdeb, Chris (9 January 2014). "Jan 9, 1978: Canadians discover thrill of defeat at the first Can-Am Bowl". Edmonton Journal. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ Puterbaugh, Travis (January 14, 2008). "Tampa Sports History: Can-Am Bowl I, 1/8/78".

- ^ Puterbaugh, Travis (January 12, 2009). "Tampa Sports History: Can-Am Bowl II, 1/6/79".

- ^ Geist, Bill (1994-10-23). "Really Big Trucks". NY Times. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ http://www.stadiumjumping.com/t.e.html#!invitational/c11xy

- ^ "Led Zeppelin | Official Website Tampa Stadium - May 5, 1973". Led Zeppelin | Official Website - Official Website. 22 September 2007.

- ^ "Official Website". Led Zeppelin. 1977-06-03. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ "The Evening Independent - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- ^ "Attention of thousands focuses on Graham crusade" The St. Pete Times, March 24, 1979

- ^ "Stadium rose despite challenges".

- ^ Tampa Still Hopeful Bucs Will Stay Put Orlando Sentinel

- ^ "Tampa Sports Authority – Raymond James Stadium".

- ^ Didtler, Mark (September 14, 1998). "Mutiny ends stadium's use". The Orlando Sentinel. p. 17. Retrieved August 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

External links

- Sports venues demolished in 1999

- Defunct college football venues

- Defunct National Football League venues

- Soccer venues in Florida

- Sports venues in Tampa, Florida

- American football venues in Florida

- Tampa Bay Buccaneers stadiums

- Tampa Bay Mutiny

- Tampa Bay Rowdies sports facilities

- Defunct NCAA bowl game venues

- ReliaQuest Bowl

- Former Major League Soccer stadiums

- United States Football League venues

- Demolished sports venues in Florida

- Defunct soccer venues in the United States

- South Florida Bulls football venues

- Tampa Spartans football

- History of Tampa, Florida

- 1967 establishments in Florida

- 1998 disestablishments in Florida

- North American Soccer League (1968–1984) stadiums

- Tampa Bay Bandits stadiums

- Sports venues completed in 1967

- Former South Florida Bulls sports venues