Székesfehérvár

Székesfehérvár | |

|---|---|

| Székesfehérvár Megyei Jogú Város | |

|

From the top, left to right: Hungarian Royal Hotel, Cathedral of Székesfehérvár, Aunt Kati statue, Árpád Spa, Episcopal Palace, and Csók István Gallery and Vörösmarty Mihály Library | |

| Nickname(s): Fehérvár Hungarian Crowning City City of Kings City of Churches | |

| Coordinates: 47°11′20″N 18°24′50″E / 47.18877°N 18.41384°E | |

| Country | |

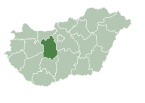

| Region | Central Transdanubia |

| County | Fejér |

| District | Székesfehérvár |

| Established | 972 |

| City status | 972 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | András Cser-Palkovics (Fidesz-KDNP) |

| • Deputy Mayor | Éva Brájer (Fidesz-KDNP) Tamás Égi (Fidesz-KDNP) Péter Róth (Fidesz-KDNP) Attila Mészáros (Fidesz-KDNP) |

| • Town Notary | Dr Viktor Bóka |

| Area | |

| 170.89 km2 (65.98 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 118 m (387 ft) |

| Population (2014) | |

| 97,617[1] | |

| • Rank | 9th |

| • Density | 571.23/km2 (1,479.5/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 272,474 (9th)[2] |

| Demonym(s) | székesfehérvári, fehérvári |

| Population by ethnicity | |

| • Hungarians | 85.0% |

| • Germans | 1.3% |

| • Gypsies | 0.8% |

| • Romanians | 0.1% |

| • Serbs | 0.1% |

| • Slovaks | 0.1% |

| • Croats | 0.1% |

| • Polish | 0.1% |

| • Ukrainians | 0.1% |

| Population by religion | |

| • Roman Catholic | 35.0% |

| • Greek Catholic | 0.3% |

| • Calvinists | 8.2% |

| • Lutherans | 1.4% |

| • Other | 1.6% |

| • Non-religious | 21.9% |

| • Unknown | 31.7% |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 8000 to 8019 |

| Area code | (+36) 22 |

| Motorways | M7 |

| NUTS 3 code | HU211 |

| Distance from Budapest | 64.2 km (39.9 mi) Southwest |

| International airports | Székesfehérvár |

| MP | Tamás Vargha (Fidesz-KDNP) Gábor Törő (Fidesz-KDNP) |

| Website | www |

The city of Székesfehérvár (Hungarian pronunciation: [ˈseːkɛʃfɛheːrvaːr] ), known colloquially as Fehérvár ("white castle"), located in central Hungary, is the ninth largest city of the country; regional capital of Central Transdanubia; and the centre of Fejér county and Székesfehérvár District. The area is an important rail and road junction between Lake Balaton and Lake Velence.

Székesfehérvár, a royal residence (székhely),[3] as capital of the Kingdom of Hungary, held a central role in the Middle Ages. As required by the Doctrine of the Holy Crown, the first kings of Hungary were crowned and buried here.[4] Significant trade routes led to the Balkans and Italy, and to Buda and Vienna. Historically the city has come under Ottoman and Habsburg control, and was known in many languages by translations of "white castle": (Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-de, Template:Lang-ota, Template:Lang-sk)

History

Pre-Hungarian

The place has been inhabited since the 5th century BC. In Roman times the settlements were called Gorsium and Herculia. After the Migration Period Fejér County was the part of the Avar Khaganate,[6] while the Slavic and Great Moravian presence is disputed. (There is no source for the name of the place before the late 10th century.) In the Middle Ages its Latin name was Alba Regalis/Alba Regia. The town was an important traffic junction between Lake Balaton and Lake Velence, several trade routes led from here to the Balkans and Italy, and to Buda and Vienna. (Today, the town is a junction of seven railroad lines.)

Early Hungarian

Grand Prince Géza of the Árpád dynasty was the nominal overlord of all seven Magyar tribes but in reality ruled only part of the united territory. He aimed to integrate Hungary into Christian Western Europe by rebuilding the state according to the Western political and social models. Géza founded the Hungarian town in 972 on four moorland islands between the Gaja stream and its tributary, the Sárvíz, one of the most important Hungarian tributaries of the Danube. He also had a small stone castle built. Székesfehérvár was first mentioned in a document by the Bishopric of Veszprém, 1009, as Alba Civitas.

Stephen I of Hungary granted town rights to the settlement, surrounded the town with a plank wall, and founded a school and a monastery.[7] Under his rule the construction of the Romanesque Székesfehérvár Basilica began (it was built between 1003 and 1038). The settlement had about 3,500 inhabitants at this time and was the royal seat for hundreds of years. 43 kings were crowned in Székesfehérvár (the last one in 1526) and 15 kings were buried here (the last one in 1540).

In the 12th century, the town prospered, churches, monasteries, and houses were built. It was an important station on the pilgrim route to the Holy Land. András II issued the Golden Bull here in 1222. The Bull included the rights of nobles and the duties of the king, and the Constitution of Hungary was based on it until 1848. It is often compared to England's Magna Charta.

During the Mongol Invasion of Hungary (1241–1242), the invaders could not get close to the castle: Kadan ruled[clarification needed] Mongol warriors could not get through the surrounding marshes because of flooding caused by melting snow. In the 13th–15th centuries, the town prospered, and several palaces were built. In the 14th century, Székesfehérvár was surrounded by city walls.

After the death of King Mátyás (1490), the German army of 20,000 men of Maximilian invaded Hungary. They advanced into the heart of Hungary and captured the city of Székesfehérvár, which he sacked, as well as the tomb of King Mátyás, which was kept there. His Landsknechts were still unsatisfied with the plunder and refused to go for taking[clarification needed] Buda. He returned to the Empire in late December and the Hungarian troops liberated Székesfehérvár in the next year.[8]

Ottoman period

The Ottomans conquered the city after a long siege in 1543 and only after a sally ended in most of the defenders including the commander, György Varkoch, being locked out by wealthy citizens fearing they might incur the wrath of the Ottomans by a lengthy siege. They discovered after surrendering, however, that the Ottomans were not without a sense for chivalry and those responsible for shutting the defenders out were put to death.

Except for a short period in 1601 when Székesfehérvár was reconquered by an army led by Lawrence of Brindisi, the city remained under Ottoman administration for 145 years, until 1688,[9] with the Ottomans being preoccupied with the Morean War. The Ottomans destroyed most of the city, they demolished the cathedral and the royal palace, and they pillaged the graves of kings in the cathedral. They named the city Belgrade ("white city", from Serbian Beograd) and built mosques. In the 16th–17th centuries it looked like a Muslim city. Most of the original population fled. It was a sanjak centre in Budin Province as "İstolni Belgrad" during Ottoman rule.

Habsburg Monarchy

The city began to prosper again only in the 18th century. It had a mixed population: Hungarians, Germans, Serbs, and Moravians.

By 1702, the cathedral of Nagyboldogasszony was blown up,[10] thus destroying the largest cathedral in Hungary at that time, and the coronation temple. By the Doctrine of the Holy Crown, all kings of Hungary were obliged to be crowned in this cathedral, and to take part in coronation ceremony in the surroundings of the cathedral. The coronations after that time were held in Pozsony (now Bratislava).

In 1703, Székesfehérvár regained the status of a free royal town. In the middle of the century, several new buildings were erected (Franciscan church and monastery, Jesuit churches, public buildings, Baroque palaces). Maria Theresa made the city an episcopal seat in 1777.

By the early 19th century, the German population was assimilated. On 15 March 1848, the citizens joined the revolution. After the revolution and war for independence, Székesfehérvár lost its importance and became a mainly agricultural city. In 1909 The Times Engineering Contract List noted a bridge construction contract valued at £12,000 to be overseen by the Chief Magistrate.[11]

Interwar period

New prosperity arrived between the two world wars, when several new factories were opened. In 1922 a radio station was established. It used two masts insulated[clarification needed] against ground, each with a height of 152 metres. The last mast of the station was demolished in 2009.

World War II

In 1944, after the occupation of Hungary by Nazi Germany, the city's Jewish population was confined to a ghetto and was eventually deported to the Auschwitz death camp, together with further 3,000 Jews from the area.[12][13] The pre-war Jewish population consisted of Neolog (Reform) and Orthodox communities with their respective synagogues, and some of its members were active Zionists.[12][13]

In December 1944, Fehérvár came under Russian artillery fire, and stiff fighting broke out as the Red Army advanced on the city.[14] The Germans had chosen to concentrate their forces to protect the 15 mile gap between Fehérvár and Lake Balaton. Whereas most of the gap consisted of marsh and difficult ground, Fehérvár was the node for eight highways and six railways.[15] Despite the heavy German defences, a Russian flying column broke through and occupied the city on 23 December;[16] the Germans were able to push them out on 22 January 1945.[17] In March 1945, the area was the battleground for the last major German offensive of World War II; but following its failure Marshal Tolbukhin broke through the German lines once more and recaptured the city on 22 March.[18] A Soviet airfield was established at nearby Szabadbattyán.[19]

After WWII

In August 1951 over 150 people were killed when two trains collided in Fehérvár.[20]

After World War II, the city was subject to industrialization, like many other cities and towns in the country. The most important factories were the Ikarus bus factory, the Videoton radio and TV factory, and the Könnyűfémmű (colloquially Köfém) aluminium processing plant, since acquired by Alcoa. By the 1970s, Székesfehérvár had swelled to more than 100,000 inhabitants (in 1945 it had only about 35,000). Several housing estates were built, but the city centre preserved its Baroque atmosphere. The most important Baroque buildings are the cathedral, the episcopal palace and the city hall.

In the past few decades, archaeologists have excavated medieval ruins (that of the Romanesque basilica and the mausoleum of St. Stephen of Hungary); they can now be visited.

At the end of the Socialist regime, all the important factories were on the verge of collapse (some eventually folded) and thousands of people lost their jobs. However, the city profited from losing the old and inefficient companies, as an abundance of skilled labour coupled with excellent traffic connections and existing infrastructure attracted numerous foreign firms seeking to invest in Hungary. Székesfehérvár became one of the prime destinations for multinational companies setting up shop in Hungary (Ford and IBM are some of them), turning the city into a success story of Hungary's transition to a market economy. A few years later Denso, Alcoa, Philips, and Sanmina-SCI Corporation also settled in the city.

Culture

Architecture

- Historical centre (Baroque, Classical) buildings

- St Stephen Cathedral and ruins of Székesfehérvár Basilica (one of the largest basilicas in medieval Europe), where the Diets were held and the crown jewels kept, seat for the coronation of the Hungarian monarch and location of royal burials and memorials.

- St Anna Chapel (Gothic, built around 1470)

- "Ruin Garden": Ruins of medieval church founded by St Stephen

- Episcopal Palace (Zopf style)

- City Hall

- Zichy Palace (Zopf style manor house, 1781)

- Serbian Quarter (12 thatched peasant houses and a Byzantine-style church, won a Europa Nostra award in 1990)

- Bory Castle (20th century). A fantastic castle-like structure built by the sculptor Jenő Bory and his wife with their own hands.

- Vörösmarty Theater, the oldest theater of the country

Statues and memorials

- Golden Bull memorial. The Golden Bull was an important charter of King András II, it was released here; the memorial is from 1972.

- Globus crucifer (a stone image of the royal symbol of power of the same name)

- Statue of György Varkoch at the supposed site of his death at the gates (see above)

- Flower clock

- Railway model exhibition

Museums and galleries

- King István Museum

- Doll Museum

- Black Eagle (Fekete Sas) Pharmacy Museum

- City Museum

- City Gallery

- Csitáry spring (mineral water source)

Population

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 23,279 | — |

| 1880 | 26,559 | +14.1% |

| 1890 | 28,539 | +7.5% |

| 1900 | 33,196 | +16.3% |

| 1910 | 37,710 | +13.6% |

| 1920 | 40,352 | +7.0% |

| 1930 | 41,890 | +3.8% |

| 1941 | 49,103 | +17.2% |

| 1945 | 35,000 | −28.7% |

| 1949 | 42,260 | +20.7% |

| 1960 | 56,978 | +34.8% |

| 1970 | 79,064 | +38.8% |

| 1980 | 103,571 | +31.0% |

| 1990 | 108,958 | +5.2% |

| 2001 | 106,869 | −1.9% |

| 2011 | 100,570 | −5.9% |

| 2019 | 96,940 | −3.6% |

Ethnic groups (2001 census):

- Hungarians - 95.7%

- Germans - 0.8%

- Roma - 0.5%

- Others - 0.5%

- No answer - 2.4%

Religions (2001 census):

- Roman Catholic - 53.8%. The city stands in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Székesfehérvár

- Calvinist - 12.1%

- Lutheran - 1.9%

- Greek Catholic - 0.5%

- Other (Christian) - 1%

- Other (non-Christian) - 0.2%

- Atheists - 19.7%

- No answer, unknown - 10.7%

Politics

The current mayor of Székesfehérvár is András Cser-Palkovics (Fidesz).

The local Municipal Assembly, elected at the 2019 local government elections, is made up of 21 members (1 Mayor, 14 Individual constituencies MEPs and 6 Compensation List MEPs) divided into this political parties and alliances:[21]

| Party | Seats | Current Municipal Assembly | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| style="background-color: Template:Fidesz/meta/color | | Fidesz | 14 | style="background-color: Template:Fidesz/meta/color |M | style="background-color: Template:Fidesz/meta/color | | style="background-color: Template:Fidesz/meta/color | | style="background-color: Template:Fidesz/meta/color | | style="background-color: Template:Fidesz/meta/color | | style="background-color: Template:Fidesz/meta/color | | style="background-color: Template:Fidesz/meta/color | | style="background-color: Template:Fidesz/meta/color | | style="background-color: Template:Fidesz/meta/color | | style="background-color: Template:Fidesz/meta/color | | style="background-color: Template:Fidesz/meta/color | | style="background-color: Template:Fidesz/meta/color | | style="background-color: Template:Fidesz/meta/color | | style="background-color: Template:Fidesz/meta/color | |

| Opposition coalition[a] | 4 | |||||||||||||||

| style="background-color: Template:Independent/meta/color | | Independent | 2 | style="background-color: Template:Independent/meta/color | | style="background-color: Template:Independent/meta/color | | ||||||||||||

| Válasz, Independets Civils | 1 | |||||||||||||||

List of mayors

List of City Mayors from 1990:

| Member | Party | Term of office | |

|---|---|---|---|

| István Balsay | style="background-color:Template:Independent (politician)/meta/color" | | Independent | 1990–1994 |

| István Nagy | style="background-color:Template:Fidesz/meta/color" | | Fidesz | 1994–1998 |

| Tihamér Warvasovszky | style="background-color:Template:Alliance of Free Democrats/meta/color" | | MSZP-SZDSZ | 1998–2010 |

| Tibor Viniczai | style="background-color:Template:Hungarian Democratic Forum/meta/color" | | MDF | 2010 |

| András Cser-Palkovics | style="background-color:Template:Fidesz/meta/color" | | Fidesz | 2010– |

Notable people

Born in Székesfehérvár

- Béla Balogh, film director

- Jenő Bory, sculptor, architect

- István Deák, historian

- George Fisher, Serbian leader of the Texas Revolution

- Ignác Goldziher, orientalist

- Katarina Ivanović, early 19th century Serbian Biedermeier painter

- Péter Kuczka, writer

- Kornél Lánczos, physicist

- Viktor Orbán, Prime Minister of Hungary in 1998—2002 and 2010–present

- Katalin Bogyay, journalist, diplomat

- Miklós Ybl, architect

- George Lang, restaurateur

- Dávid Disztl, Professional Football player

- Dominik Szoboszlai, Professional Football player

Buried royalty

- Prince Saint Emeric of Hungary (1031)

- King Saint Stephen (1038)

- Coloman the Bookish (1116)

- Álmos the Blind (1129)

- Béla the Blind (1141)

- Géza II (1162)

- Stephen IV (1165)

- Agnes of Antioch (1184)

- Béla III (1196)

- Ladislaus III (1205)

- Charles I of Hungary (1342)

- Louis the Great (1382)

- Albert the Magnanimous (1439)

- Matthias Corvinus (1490)

- Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary (1516)

- Louis II (1526)

Fictional

- Albert Horn, character in Louis Malle's film Lacombe, Lucien.

Sport

Alba Regia Sportcsarnok is an indoor stadium in the city. It hosts a number of sport clubs from amateur to professional level, with 2017 Hungarian basketball championship winner Alba Fehérvár being its most notable tenant.

Other city sports clubs include:

- Videoton FC (football)

- Székesfehérvári MÁV Előre SC (football)

- Székeshfehervar Alba Volan HC (ice hockey)

- Alba Fehérvár KC (handball)

- Fehérvár Enthroners American Football SE

- Székesfehérvári Kempo SE (martial arts)

- Profi Kempo Akadémia - PKA

Transport

Székesfehérvár is an important hub for the Hungarian railway system (MÁV). Trains depart to the Northern Coast of Lake Balaton and towards the capitol. The city is also reachable by regional buses from other major national destinations. There are numerous local buslines operating 7 days a week, operated by the company that also operates the regional buses in the region, KNYKK Zrt. (Közép-Nyugat Magyarországi Közlekedési Központ).

Twin towns - Sister cities

Székesfehérvár is twinned with:[22]

Alba Iulia in Romania[22]

Alba Iulia in Romania[22] Banská Štiavnica in Slovakia[22]

Banská Štiavnica in Slovakia[22] Birmingham, Alabama, in United States[22][23][24][25]

Birmingham, Alabama, in United States[22][23][24][25] Blagoevgrad in Bulgaria[22]

Blagoevgrad in Bulgaria[22] Bratislava, Slovakia[26]

Bratislava, Slovakia[26] Cento in Ferrara, Emilia-Romagna, Italy[22]

Cento in Ferrara, Emilia-Romagna, Italy[22] Changchun in China[22]

Changchun in China[22] Chorley, Lancashire, England, United Kingdom (since 1991)[22]

Chorley, Lancashire, England, United Kingdom (since 1991)[22] Erdenet in Mongolia[22]

Erdenet in Mongolia[22] Kemi in Finland[22]

Kemi in Finland[22] Kocaeli in Turkey[22]

Kocaeli in Turkey[22] Luhansk in Ukraine[22]

Luhansk in Ukraine[22] Miercurea Ciuc in Romania

Miercurea Ciuc in Romania Opole in Opole Voivodeship, Poland[22][27]

Opole in Opole Voivodeship, Poland[22][27] Schwäbisch Gmünd in Baden-Württemberg, Germany[22]

Schwäbisch Gmünd in Baden-Württemberg, Germany[22] Zadar in Croatia[22]

Zadar in Croatia[22]

See also

References

- Székesfehérvár, a királyi város (Székesfehérvár, the royal city)

- ^ a b c KSH - Székesfehérvár, 2011

- ^ Eurostat, 2016

- ^ szék meaning "seat", i.e. "throne")

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ British Museum Collection

- ^ See: Bóna István: Avar lovassír Iváncsáról [Grave of an Avar horseman at Iváncsa]. In: ArchÉrt 97. (1970). 243–264.

- ^ Previously rendered as "provosty"; there is no such word in English but there is in German, see [1]

- ^ József Bánlaky (1929). "Ulászló küzdelmei János Albert lengyel herceggel és Miksa római királlyal. Az 1492. évi budai országgyűlés főbb határozatai." [Struggle of Vladislas against prince John Albert and Holy Roman Emperor Maxinmilan. The assembly of Buda in 1492 and its sanctions.]. A magyar nemzet hadtörténelme [Military history of the Hungarian nation] (in Hungarian). Budapest, Hungary: Grill Károly Könyvkiadó vállalata. ISBN 963-86118-7-1. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ Alban Butler, Paul Burns (2000). Butler's Lives of the Saints. p. 159. ISBN 0-86012-256-5.

- ^ Ferenc Glatz: Magyar történeti kronológia

- ^ The Times (London, England), 15 December 1909; pg. 18

- ^ a b city in central Hungary at the Beit Hatfutsot (Jewish Diaspora Museum, Tel Aviv) website

- ^ a b The Jews of Szekesfehervar & Its Environs, by Dr. Eliezer Even (Koves) & Bemjamin Ravid, Jerusalem, 1997

- ^ Red Army Eight Miles From Budapest.” The Times 11 December 1944; pg. 4

- ^ “Drive Towards The Danube.” The Times (London, England), 27 December 1944; pg. 4

- ^ Outflanking Budapest. The Times (London, England), 9 December 1944; pg. 4

- ^ East Prussia Or Silesia?. The Times, 23 January 1945

- ^ Progress Towards Györ, The Times (London, England), Monday, Mar 26, 1945; pg. 4

- ^ Forced Labour Units In Hungary. The Times, 2 January 1952

- ^ Strain On Railways In Hungary. The Times, 16 November 1951

- ^ "Városi közgyűlés tagjai 2019-2024 - Székesfehérvár (Fejér megye)". valasztas.hu. Retrieved 2019-10-29.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Bozsoki, Agnes. "Partnervárosok Névsora Partner és Testvérvárosok Névsora" [Partner and Twin Cities List]. City of Székesfehérvár (in Hungarian). Archived from the original on 2012-12-08. Retrieved 2013-08-05.

- ^ "Székesfehérvár twin cities" (in Hungarian). Székesfehérvár.hu. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- ^ "Upcoming Birmingham Sister City Visitors" (PDF). Archived from the original (pdf) on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- ^ "Birmingham USA - Sister Cities". birminghamsistercities.com. April 23, 1982. Retrieved 2012-07-14.

- ^ "Partner (Twin) towns of Bratislava". Bratislava-City.sk. Archived from the original on 2013-07-28. Retrieved 2013-08-05.

- ^ "Miasta Partnerskie Opola". Urzad Miasta Opola (in Polish). Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- Notes