Luchino Visconti

Luchino Visconti | |

|---|---|

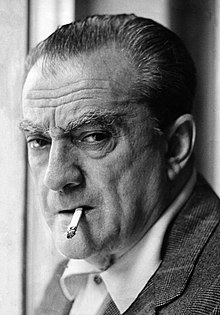

Visconti in 1972 | |

| Born | Luchino Visconti di Modrone 2 November 1906 |

| Died | 17 March 1976 (aged 69) |

| Relatives | Eriprando Visconti (nephew) |

| Awards | Palme d'Or 1963 The Leopard Golden Lion 1965 Vaghe stelle dell'Orsa |

Luchino Visconti di Modrone, Count of Lonate Pozzolo (Italian: [luˈkiːno visˈkonti di moˈdroːne]; 2 November 1906 – 17 March 1976), was an Italian theatre, opera and cinema director, as well as a screenwriter. Visconti was one of the fathers of Italian neorealism in film, but later moved towards luxurios-looking films obsessed with beauty, death and European history – especially the decay of aristocracy. Among his best-known films are Ossessione (1943), Senso (1954), Rocco and His Brothers (1960), The Leopard[1] (1963), The Damned (1969), Death in Venice (1971) and Ludwig (1972).

Biography

Luchino Visconti was born into a prominent noble family in Milan, one of seven children of Giuseppe Visconti di Modrone, Duke of Grazzano Visconti and Count of Lonate Pozzolo, and his wife Carla[2] (née Erba, heiress to Erba Pharmaceuticals). He was formally known as Count don Luchino Visconti di Modrone, and his family is a branch of the Visconti of Milan. In his early years, he was exposed to art, music and theatre: he studied cello with the Italian cellist and composer Lorenzo de Paolis (1890–1965) and met the composer Giacomo Puccini, the conductor Arturo Toscanini and the writer Gabriele D'Annunzio.[citation needed]

During World War II, Visconti joined the Italian Communist Party.[citation needed]

Visconti made no secret of his bisexuality. His last partner was the Austrian actor Helmut Berger, who played Martin in Visconti's film The Damned.[3] Berger also appeared in Visconti's Ludwig in 1973 and Conversation Piece in 1974, along with Burt Lancaster. Other lovers included Franco Zeffirelli,[4] who also worked as part of the crew in production design, as assistant director, and other roles in a number of Visconti's films, operas, and theatrical productions.

According to Visconti's autobiography, he and Umberto II of Italy had a homosexual relationship during their youth in the 1920s.[5]

Visconti smoked 120 cigarettes a day.[6] He suffered a stroke in 1972, but continued to smoke heavily.[citation needed] He died in Rome of another stroke at the age of 69, on 17 March 1976.[citation needed] There is a museum dedicated to the director's work in Ischia.[citation needed]

Career

Films

He began his filmmaking career as an assistant director on Jean Renoir's Toni (1935) and Partie de campagne (1936) through the intercession of their common friend Coco Chanel.[7] After a short tour of the United States, where he visited Hollywood, he returned to Italy to be Renoir's assistant again, this time for Tosca (1941), a production that was interrupted and later completed by German director Karl Koch.

Together with Roberto Rossellini, Visconti joined the salotto of Vittorio Mussolini (the son of Benito, who was then the national arbitrator for cinema and other arts).[citation needed] Here he presumably also met Federico Fellini. With Gianni Puccini, Antonio Pietrangeli and Giuseppe De Santis, he wrote the screenplay for his first film as director: Ossessione (Obsession, 1943), one of the first neorealist movies and an unofficial adaptation of the novel The Postman Always Rings Twice.[8]

In 1948, he wrote and directed La terra trema (The Earth Trembles), based on the novel I Malavoglia by Giovanni Verga. Visconti continued working throughout the 1950s, but he veered away from the neorealist path with his 1954 film, Senso, shot in colour. Based on the novella by Camillo Boito, it is set in Austrian-occupied Venice in 1866. In this film, Visconti combines realism and romanticism as a way to break away from neorealism. However, as one biographer notes, "Visconti without neorealism is like Lang without expressionism and Eisenstein without formalism".[9] He describes the film as the "most Viscontian" of all Visconti's films. Visconti returned to neorealism once more with Rocco e i suoi fratelli (Rocco and His Brothers, 1960), the story of Southern Italians who migrate to Milan hoping to find financial stability. In 1961, he was a member of the jury at the 2nd Moscow International Film Festival.[10]

Throughout the 1960s, Visconti's films became more personal. Il Gattopardo (The Leopard, 1963) is based on Lampedusa's novel of the same name about the decline of the Sicilian aristocracy at the time of the Risorgimento. It starred American actor Burt Lancaster in the role of Prince Don Fabrizio. This film was distributed in America and Britain by Twentieth-Century Fox, which deleted important scenes. Visconti repudiated the Twentieth-Century Fox version.[citation needed]

It was not until The Damned (1969) that Visconti received a nomination for an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. The film, one of Visconti's better known works, concerns a German industrialist's family which begins to disintegrate during the Nazi consolidation of power in the 1930s. Its decadence and lavish beauty are characteristic of Visconti's aesthetic.

Visconti's final film was The Innocent (1976), in which he returns to his recurring interest in infidelity and betrayal.

Theatre

Visconti was also a celebrated theatre and opera director. During the years 1946 to 1960 he directed many performances of the Rina Morelli-Paolo Stoppa Company with actor Vittorio Gassman as well as many celebrated productions of operas.

Visconti's love of opera is evident in the 1954 Senso, where the beginning of the film shows scenes from the fourth act of Il trovatore, which were filmed at the Teatro La Fenice in Venice. Beginning when he directed a production at Milan's Teatro alla Scala of La vestale in December 1954, his career included a famous revival of La traviata at La Scala in 1955 with Maria Callas and an equally famous Anna Bolena (also at La Scala) in 1957 with Callas. A significant 1958 Royal Opera House (London) production of Verdi's five-act Italian version of Don Carlos (with Jon Vickers) followed, along with a Macbeth in Spoleto in 1958 and a famous black-and-white Il trovatore with scenery and costumes by Filippo Sanjust at the Royal Opera House in 1964. In 1966 Visconti's luscious Falstaff for the Vienna State Opera conducted by Leonard Bernstein was critically acclaimed. On the other hand, his austere 1969 Simon Boccanegra with the singers clothed in geometrical costumes provoked controversy.

Filmography

Feature films

| Year | Original title | International English title | Awards |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1943 | Ossessione | Obsession | |

| 1948 | La terra trema | The Earth Will Tremble | Special International Award — 9th Venice International Film Festival Nominated – Grand International Prize of Venice — 9th Venice International Film Festival |

| 1951 | Bellissima | Bellissima | |

| 1954 | Senso | Senso or The Wanton Countess | Nominated – Golden Lion — 15th Venice International Film Festival |

| 1957 | Le notti bianche | White Nights | Silver Lion Prize – 18th Venice International Film Festival Nominated – Golden Lion — 18th Venice International Film Festival |

| 1960 | Rocco e i suoi fratelli | Rocco and His Brothers | Special Prize – 21st Venice International Film Festival FIPRESCI Prize – 21st Venice International Film Festival 1961 Nastro d'Argento for Best Director 1961 Nastro d'Argento for Screenplay Nominated – Golden Lion — 21st Venice International Film Festival |

| 1963 | Il gattopardo | The Leopard | Palme d'Or – 1963 Cannes Film Festival |

| 1965 | Vaghe stelle dell'Orsa | Sandra | Golden Lion — 26th Venice International Film Festival |

| 1967 | Lo straniero | The Stranger | Nominated – Golden Lion — 28th Venice International Film Festival |

| 1969 | La caduta degli dei | The Damned | 1970 Nastro d'Argento for Best Director Nominated – Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay — 42nd Academy Awards |

| 1971 | Morte a Venezia | Death in Venice | 25th Anniversary Prize — 1971 Cannes Film Festival David di Donatello for Best Director — 16th David di Donatello Awards 1972 Nastro d'Argento for Best Director Nominated — Palme d'Or — 1971 Cannes Film Festival Nominated — BAFTA Award for Best Film — 25th British Academy Film Awards Nominated — BAFTA Award for Best Direction — 25th British Academy Film Awards |

| 1973 | Ludwig | Ludwig | David di Donatello for Best Director — 18th David di Donatello Awards |

| 1974 | Gruppo di famiglia in un interno | Conversation Piece | 1975 Nastro d'Argento for Best Director |

| 1976 | L'innocente | The Innocent |

Other films

- Giorni di gloria, documentary, 1945

- Appunti su un fatto di cronaca, short film, 1951

- Siamo donne (We, the Women), 1953, episode Anna Magnani

- Boccaccio '70, 1962, based on the episode Il lavoro in Boccaccio's Decameron

- Le streghe (The Witches), 1967, episode La strega bruciata viva

- Alla ricerca di Tadzio, TV movie, 1970

Opera

| Year | Title and Composer | Opera House | Principal cast / Conductor |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1954 | La vestale, Gaspare Spontini |

La Scala | Maria Callas, Franco Corelli, Ebe Stignani, Nicola Zaccaria Conducted by Antonino Votto[11] |

| 1955 | La sonnambula, Vincenzo Bellini, |

La Scala | Maria Callas, Cesare Valletti, Giuseppe Modesti Conducted by Leonard Bernstein[12] |

| 1955 | La traviata, Giuseppe Verdi |

La Scala | Maria Callas, Giuseppe Di Stefano, Ettore Bastianini Conducted by Carlo Maria Giulini[13] |

| 1957 | Anna Bolena, Gaetano Donizetti |

La Scala | Maria Callas, Giulietta Simionato, Nicola Rossi-Lemeni Conducted by Gianandrea Gavazzeni[14] |

| 1957 | Iphigénie en Tauride, Christoph Willibald Gluck |

La Scala | Maria Callas, Franceso Albanese, Anselmo Colzani, Fiorenza Cossotto Conducted by Nino Sanzogno[15] |

| 1958 | Don Carlo, Verdi | Royal Opera House, London |

Jon Vickers, Tito Gobbi, Boris Christoff, Gré Brouwenstijn Conducted by Carlo Maria Giulini[16] |

| 1958 | Macbeth, Verdi | Spoleto Festival | William Chapman & Dino Dondi; Ferruccio Mazzoli & Ugo Trama;Shakeh Vartenissian. Conducted by Thomas Schippers[17] |

| 1959 | Il duca d'Alba, Donizetti | Spoleto Festival[18] | Luigi Quilico, Wladimiro Ganzarolli, Franco Ventriglia, Renato Cioni, Ivana Tosini. Conductor: Thomas Schippers[19] |

| 1961 | Salome, Richard Strauss | Spoleto Festival[18] | George Shirley, Lili Chookasian, Margarei Tynes, Robert Anderson, Paul Arnold. Conductor: Thomas Schippers[19] |

| 1963 | Il diavolo in giardino, Franco Mannino (1963) |

Teatro Massimo, Palermo[18] | Ugo Benelli, Clara Petrella, Gianna Galli, Antonio Annaloro, Antonio Boyer. Conductor: Enrico Medioli. Libretto: Visconti & Filippo Sanjust[19] |

| 1963 | La traviata, Verdi | Spoleto Festival | Franca Fabbri, Franco Bonisolli, Mario Basiola Conducted by Robert La Marchina[20] |

| 1964 | Le nozze di Figaro, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart |

Teatro dell'Opera di Roma[21] | Rolando Panerai, Uva Ligabue, Ugo Trama, Martella Adani, Stefania Malagù. Conductor: Carlo Maria Giulini[19] |

| 1964 | Il trovatore | Bolshoi Opera, Moscow (September) | Pietro Cappuccilli, Gabriella Tucci, Giulietta Simionato, Carlo Bergonzi Conducted by Gianandrea Gavazzeni[22] |

| 1964 | Il trovatore, Verdi | Royal Opera House, London (November) (Sanjust production) |

Peter Glossop, Gwyneth Jones & Leontyne Price, Giulietta Simionato, Bruno Prevedi Conducted by Carlo Maria Giulini[23] |

| 1965 | Don Carlo, Verdi | Teatro dell'Opera di Roma | Cesare Siepi, Gianfranco Cecchele, Kostas Paskalis, Martti Talvela, Suzanne Sarroca, Mirella Boyer. Conducted by Carlo Maria Giulini.[24] |

| 1966 | Falstaff, Verdi | Vienna Staatsoper | Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Rolando Panerai, Murray Dickie, Erich Kunz, Ilva Ligabue, Regina Resnik. Conducted by Leonard Bernstein[25] |

| 1966 | Der Rosenkavalier, Strauss | Royal Opera House, London[21] | Sena Jurinac, Josephine Veasey, Michael Langdon. Conductor: Georg Solti[26] |

| 1967 | La traviata, Verdi | Royal Opera House, London | Mirella Freni, Renato Cioni, Piero Cappuccilli. Conducted by Carlo Maria Giulini[27] |

| 1969 | Simon Boccanegra, Verdi | Vienna Staatsoper | Eberhard Wächter, Nicolai Ghiaurov, Gundula Janowitz, Carlo Cossutta Conducted by Josef Krips[28] |

| 1973 | Manon Lescaut, Giacomo Puccini |

Spoleto Festival[21] | Nancy Shade, Harry Theyard, Angelo Romero, Carlo Del Bosco. Conductor: Thomas Schippers.[19] |

References

Notes

- ^ 'THE LEOPARD' IN ITS ORIGINAL LAIR: Care and Authenticity Mark screen Version of Modern Classic By HERBERT MITGANG. New York Times 29 July 1962: 69

- ^ "M/M Icon: Luchino Visconti", Manner of Man Magazine online at mannerofman.com, 2 November 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2012

- ^ "The Damned". Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ Silva, Horacio, "The Aristocrat", The New York Times, 17 September 2006. (Overview of Visconti's life and career) Retrieved 7 November 2011

- ^ Dall'Oroto, Giovanni "Umberto II" from Who's Who in Contemporary Gay and Lesbian History, London: Psychology Press, 2002 p. 453.

- ^ Thomson, David (15 February 2003). "The decadent realist". Retrieved 26 December 2017 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ Bacon, Henry (1998). Visconti: Explorations of Beauty and Decay. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 6. ISBN 9780521599603.

- ^ Bacon, Henry (1998). Visconti: Explorations of Beauty and Decay. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 14. ISBN 9780521599603.

- ^ Nowell-Smith, p. 9.

- ^ "2nd Moscow International Film Festival (1961)". MIFF. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ Ardoin 1977, p. 89

- ^ Ardoin 1977, p. 93

- ^ Ardoin 1977, p. 96

- ^ Ardoin 1977, p. 120

- ^ Ardoin 1977, p. 123

- ^ Viscontiana 2001, p. 113

- ^ Viscontiana 2001, pp. 62–63

- ^ a b c Viscontiana 2001, p. 142

- ^ a b c d e "Lirica": Operas directed by Visconti on luchinovisconti.net

- ^ Viscontiana 2001, p. 64

- ^ a b c Viscontiana 2001, p. 143

- ^ Viscontiana 2001, p. 65

- ^ Viscontiana 2001, p. 65–66

- ^ Viscontiana 2001, p. 66

- ^ Viscontiana 2001, pp. 66–67

- ^ Royal Opera House performance archive for 21 April 1966 on rohcollections.org.uk

- ^ Viscontiana 2001, p. 67

- ^ Viscontiana 2001, p. 68

Sources

- Ardoin, John, The Callas Legacy, London: Duckworth, 1977 ISBN 0-7156-0975-0

- Bacon, Henry, Visconti: Explorations of Beauty and Decay, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998 ISBN 0-521-59960-1

- Düttmann, Alexander García, Visconti: Insights into Flesh and Blood, translated by Robert Savage, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009 ISBN 9780804757409

- Glasenapp, Jörg (ed.): Luchino Visconti (= Film-Konzepte, vol. 48). Munich: edition text + kritik 2017.

- Iannello, Silvia, Le immagini e le parole dei Malavoglia Roma: Sovera, 2008 (in Italian)

- Nowell-Smith, Geoffrey, Luchino Visconti. London: British Film Institute, 2003. ISBN 0-85170-961-3

- Visconti bibliography, University of California Library, Berkeley. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Viscontiana: Luchino Visconti e il melodramma verdiano, Milan: Edizioni Gabriele Mazzotta, 2001. A catalog for an exhibition in Parma of artifacts relating to Visconti's productions of operas by Verdi, curated by Caterina d'Amico de Carvalho, in Italian. ISBN 88-202-1518-7

External links

- Luchino Visconti at IMDb

- Biography, Filmography and More on Luchino Visconti (in Italian)

- British Film Institute: "Luchino Visconti": filmography

- Hutchison, Alexander, "Luchino Visconti's Death in Venice", Literature/Film Quarterly, v. 2, 1974. (In-Depth Analysis of Death in Venice).

- Luchino Visconti at Find a Grave

- 1906 births

- 1976 deaths

- Bisexual men

- Directors of Palme d'Or winners

- Directors of Golden Lion winners

- Giallo film directors

- House of Visconti

- Italian nobility

- Italian film directors

- Italian Marxists

- Italian opera directors

- Italian communists

- LGBT directors

- LGBT writers from Italy

- David di Donatello winners

- Nastro d'Argento winners

- Deaths from cerebrovascular disease