Timeline of the London Underground

| Part of a series on the |

| London Underground |

|---|

|

|

|

The transport system now known as the London Underground began in 1863 with the Metropolitan Railway, the world's first underground railway. Over the next forty years, the early sub-surface lines reached out from the urban centre of the capital into the surrounding rural margins, leading to the development of new commuter suburbs. At the turn of the nineteenth century, new technology—including electric locomotives and improvements to the tunnelling shield—enabled new companies to construct a series of "tube" lines deeper underground. Initially rivals, the tube railway companies began to co-operate in advertising and through shared branding, eventually consolidating under the single ownership of the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL), with lines stretching across London.

In 1933, the UK Government amalgamated the UERL and the Metropolitan Railway as a single organisation, named the London Passenger Transport Board. The London Underground has since passed through a series of administrations, expanding further by the construction of new extensions and through the acquisition of existing main line routes, culminating in its current form as part of Transport for London, the capital's current transport administration, controlled by the Greater London Authority.

This timeline lists significant dates in the history of the network. Station names shown are current names; many stations have previously had different names.

| Contents |

|---|

|

1820s 1840s 1850s 1860s 1870s 1880s 1890s 1900s 1910s 1920s 1930s 1940s 1950s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s 2000s 2010s |

1820s

- 1825

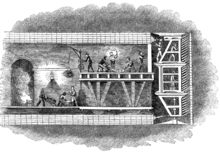

- Using his patented tunnelling shield, Marc Brunel begins construction of the Thames Tunnel under the River Thames between Wapping and Rotherhithe. Progress is slow and will be halted a number of times before the tunnel is completed.[1]

1840s

- 1843

- The Thames Tunnel opens as a pedestrian tunnel.[2]

- 1845

- Charles Pearson, Solicitor to the City of London, begins promoting the idea of an underground railway to bring passenger and goods services into the centre of the City.[3]

1850s

- 1854

- Metropolitan Railway (MR) is incorporated and granted powers to construct an underground railway from Paddington to Farringdon.[4]

- 1856

- Eastern Counties Railway (ECR) opens a line from Leyton to Loughton.[5]

1860s

- 1860

- Aylesbury and Buckingham Railway (A&BR) is incorporated.[6]

- 1862

- Edgware, Highgate and London Railway (EH&LR) is incorporated to build a railway between Finsbury Park and Edgware.[7]

- 1863

- MR opens the first underground railway in the world.[8]

- 1864

- MR opens the Hammersmith & City Railway, its first extensions to Hammersmith and to Kensington Olympia.[8]

- District Railway (DR) is incorporated.[9][10]

- North Western and Charing Cross Railway (NW&CCR) granted powers to construct an underground line from Euston to Charing Cross.[11]

- 1865

- MR extends to Moorgate.[8]

- East London Railway (ELR) purchases the Thames Tunnel for conversion to a railway tunnel.[2]

- ECR extends to Ongar.[5]

- 1867

- EH&LR opens between Finsbury Park and Edgware.[12]

- 1868

- MR opens the Metropolitan and St John's Wood Railway, a short branch northward from Baker Street to Swiss Cottage,[8] the first section of the company's eventual extensions into Middlesex, Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire.

- DR opens between South Kensington and Westminster. The MR extends to connect to the DR at South Kensington and both companies operate services over the other's tracks.[8]

- A&BR opens between Aylesbury and Verney Junction.[13]

- 1869

- DR extends from Gloucester Road to West Brompton.[8]

- ELR opens between New Cross Gate and Wapping. First use of Thames Tunnel for trains.[2]

- London and South Western Railway (L&SWR) opens line from West London Line to Richmond.[14]

- NW&CCR plans are abandoned.[11]

1870s

- 1870

- Tower Subway opens, briefly, using a cabled-hauled carriage before conversion to pedestrian use. Constructed using a circular tunnelling shield developed by Peter W. Barlow and James Henry Greathead and lined with segmental cast-iron rings, this short tunnel under the River Thames successfully demonstrated new tunnelling techniques that would be used to construct most of the subsequent underground lines in London.[15]

- DR extends from Westminster to Blackfriars.[8]

- 1871

- DR extends from Blackfriars to Mansion House.[8]

- Euston, St Pancras and Charing Cross Railway revives NW&CCR's plans for an underground line from Euston to Charing Cross and changes its name to London Central Railway (LCR).[16]

- Brill Tramway opens between the A&BR's station at Quainton Road and Wood Siding.[13]

- 1872

- Brill Tramway extends to Brill.[13]

- DR extends from Earl's Court to Kensington Olympia.[8]

- Great Northern Railway (GNR) extends E&HLR from East Finchley to High Barnet.[17]

- 1873

- GNR extends EH&LR from Highgate to Alexandra Palace.[18]

- 1874

- DR extends from Earl's Court to Hammersmith.[8]

- City of London financiers establish Metropolitan Inner Circle Completion Railway to complete the Inner Circle by linking the DR's terminus at Mansion House with the MR's planned terminus at Aldgate.[19]

- LCR plans are abandoned.[16]

- 1875

- MR extends to Liverpool Street.[8]

- 1876

- MR extends to Aldgate.[8]

- ELR extends from Whitechapel to Shoreditch.[2]

- 1877

- DR extends from Hammersmith to connect to the L&SWR at Ravenscourt Park. DR and MR commence services over the L&SWR to Richmond.[8]

- 1879

- MR extends to Willesden Green.[8]

- MR takes over Metropolitan Inner Circle Completion Railway.[19]

- DR extends from Turnham Green to Ealing Broadway.[8]

1880s

- 1880

- MR extends to Harrow on the Hill.[8]

- DR extends from West Brompton to Putney Bridge.[8]

- ELR opens a spur to New Cross (South Eastern Railway)

- 1882

- MR extends from Aldgate to Tower of London.[8]

- 1883

- DR commences a service over Great Western Railway (GWR) via Slough to Windsor & Eton Central.[8]

- DR extends from Acton Town to Hounslow Town.[8]

- 1884

- City of London and Southwark Subway established to build a railway from the City of London to Elephant & Castle.[20]

- DR extends from Osterley & Spring Grove to Hounslow West.[8]

- MR and DR connect Mansion House with Tower of London, completing the Inner Circle.[8]

- MR and DR extend east to St Mary's (Whitechapel Road) and connect to ELR with services running to New Cross and New Cross Gate.[8]

- DR extends to Whitechapel.[8]

- 1885

- MR extends to Pinner.[8]

- DR withdraws Ealing Broadway to Windsor & Eton Central service.[8]

- 1886

- DR closes Hounslow Town spur.[8]

- 1887

- MR extends to Rickmansworth.[8]

- 1889

- MR extends to Chesham.[8]

- DR connects to L&SWR at East Putney and commences services to Wimbledon.[8]

1890s

- 1890

- City of London and Southwark Subway changes name to City and South London Railway (C&SLR),[21] and opens between Stockwell and King William Street, the world's first deep-level underground and electric railway.[8]

- Central London Railway (CLR) incorporated to build a tube railway from Bank to Shepherd's Bush.[22]

- 1891

- MR takes over A&BR between Aylesbury and Verney Junction.[8]

- 1892

- MR extends from Chalfont & Latimer to Aylesbury.[8]

- Great Northern & City Railway (GN&CR) granted powers to build a tube railway from Finsbury Park to Moorgate.[23]

- 1893

- Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway (CCE&HR) granted powers to build a tube railway from Strand to Hampstead.[24]

- Baker Street and Waterloo Railway (BS&WR) granted powers to build a tube railway from Waterloo to Baker Street.[25]

- 1897

- Brompton and Piccadilly Circus Railway granted powers to build a tube railway from Piccadilly Circus to South Kensington.[26]

- DR obtains powers to construct a tube railway from Gloucester Road to Mansion to run below its sub-surface line.[26]

- Anarchists bomb a MR train which explodes at Barbican, injuring 60 and killing one.[27]

- Whitaker Wright's London & Globe Finance Corporation purchases BS&WR.[28]

- 1898

- City and Brixton Railway granted powers to build a tube railway from King William Street to Brixton.[29]

- Waterloo and City Railway opens between Waterloo and Bank.[8]

- 1899

- Great Northern and Strand Railway granted powers to build a tube railway from Wood Green to Strand.[30]

- MR services commence over the Brill Tramway.[8]

1900s

- 1900

- C&SLR closes King William Street and extends north to Moorgate and south to Clapham Common.[8]

- CLR opens between Bank and Shepherd's Bush.[8]

- Consortium led by Charles Yerkes takes over CCE&HR.[31]

- London & Globe Finance Corporation and BS&WR collapse following Whitaker Wright's fraudulent concealment of large losses.[32]

- 1901

- C&SLR extends to Angel.[8]

- Yerkes consortium takes over DR, Brompton and Piccadilly Circus Railway and Great Northern and Strand Railway and merges the tube routes to form the Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway (GNP&BR).[33]

- 1902

- Yerkes consortium takes over BS&WR.[33]

- Yerkes establishes the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL) as the holding company of the tube lines under his consortium's control.[33]

- DR extends from Whitechapel to Bromley-by-Bow and commences a service from there over the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway to Upminster.[8]

- Edgware & Hampstead Railway incorporated to build a railway from Golders Green to Edgware.[34]

- 1903

- C&SLR takes over City and Brixton Railway and allows its plans to lapse.[35]

- DR extends from Ealing Common to South Harrow.[8]

- DR reopens Hounslow Town spur.[8]

- Watford and Edgware Railway incorporated to build a railway from Edgware to Watford.[36]

- CCE&HR takes over Edgware & Hampstead Railway.[37]

- Great Eastern Railway opens Fairlop Loop from Ilford to Woodford via Hainult.[38]

- 1904

- GN&CR opens between Finsbury Park and Moorgate.[8]

- MR opens branch from Harrow-on-the-Hill to Uxbridge.[8]

- Whitaker Wright commits suicide by swallowing cyanide after being convicted of fraud.[32]

- 1905

- UERL opens Lots Road Power Station to provide electricity for the DR and the UERL's forthcoming tube lines.[39]

- MR and DR replace steam trains with electric over majority of routes.[40]

- DR withdraws service between East Ham and Upminster.[8]

- DR opens branch from Acton Town to South Acton.[8]

- DR withdraws service between St Mary's (Whitechapel Road) and New Cross.[8]

- Charles Yerkes dies and is replaced as Chairman of the UERL by Edgar Speyer.[41]

- 1906

- Sir George Gibb becomes Managing Director of UERL.[42]

- Frank Pick, later Managing Director and Vice Chairman of London Transport, begins work at UERL.[43]

- MR withdraws services between Hammersmith and Richmond.[8]

- BS&WR opens between Elephant & Castle and Baker Street.[8] It becomes known as the Bakerloo tube.

- GNP&BR opens between Finsbury Park and Hammersmith.[8] It becomes known as the Piccadilly tube.

- MR withdraws service between St Mary's (Whitechapel Road) and New Cross, pending electrification of the ELR.[8][40]

- 1907

- Albert Stanley, later Chairman of London Transport, begins work at UERL.[44]

- C&SLR extends to Euston.[8]

- CCE&HR opens between Golders Green, Archway and Charing Cross.[8] It becomes known as the Hampstead tube.

- Piccadilly tube opens branch from Holborn to Aldwych.[8]

- Bakerloo tube extends to Edgware Road.[8]

- 1908

- CLR extends to Wood Lane.[8]

- DR restarts service between East Ham and Barking.[8]

- The underground railway companies begin to use the "Underground" brand for joint marketing.[45]

- First version of the Underground roundel comes into use—a solid red disk with a bar carrying station names is based on a device used by the London General Omnibus Company.[46]

- 1909

- DR closes Hounslow Town spur again.[8]

1910s

- 1910

- District line extends from South Harrow to connect to the MR at Rayners Lane and commences services to Uxbridge.[8]

- District line starts excursion services from Upminster to Southend-on-Sea.[8]

- Separate managements of the Bakerloo tube, Hampstead tube and Piccadilly tube companies merge into a single company—the London Electric Railway (LER).[47][48] The lines continue to be identified by individual names.

- 1911

- First escalators come into use at Earl's Court.[49]

- 1912

- CLR extends to Liverpool Street.[8]

- 1913

- UERL purchases the C&SLR and CLR.[50]

- MR takes control of the ELR and the GN&CR.[50]

- Following electrification of the ELR, MR restarts service between St Mary's (Whitechapel Road) and New Cross. MR starts service from Whitechapel to Shoreditch and Surrey Quays to New Cross Gate.[8][40]

- Bakerloo tube extends to Paddington.[8]

- 1914

- Hampstead tube extends to Embankment.[8]

- 1915

- Bakerloo tube extends to Willesden Junction.[8]

- MR begins publication of Metro-land its annual guide promoting the use of its line for commuting and leisure. The name becomes synonymous with the developing suburbs north-west of the capital served by the railway.[51]

- Sir Edgar Speyer resigns as Chairman of the Underground Group following attacks in the press regarding his Germany origins.[41] He is replaced by Lord George Hamilton.[52]

- 1916

- Edward Johnston designs the "Underground" typeface that now bears his name and is used by Transport for London for all transport related purposes.[53]

- 1917

- Edward Johnston re-designs the Underground's disk and bar roundel, to suit his new typeface, turning the disk into a ring.[46]

- 1917

- Bakerloo tube extends to Watford Junction.[8]

- 1919

- Sir Albert Stanley replaces Lord George Hamilton as Chairman of the Underground Group.[44]

1920s

- 1920

- CLR extends from Wood Lane to Ealing Broadway.[8]

- 1922

- Underground Group purchases unbuilt Watford and Edgware Railway to extend the Hampstead tube to Watford.[54]

- 1923

- Hampstead tube extends to Hendon Central.[8]

- 1924

- Hampstead tube extends to Edgware.[8]

- C&SLR extends from Euston to connect to Hampstead tube at Camden Town.[8]

- 1925

- MR extends from Moor Park to Watford.[8]

- 1926

- Hampstead tube links Embankment to Kennington and C&SLR extends to Morden, completing the integration of the two lines.[8]

- 1929

- 55 Broadway opens as headquarters of the Underground Group.[55]

1930s

- 1932

- MR extends to Stanmore.[8]

- Piccadilly line extends from Finsbury Park to Arnos Grove.[8]

- Piccadilly line extends over District line from Hammersmith to South Harrow.[8]

- District line services restart between Barking and Upminster.[8]

- MR ends publication of Metro-land.[51]

- 1933

- Piccadilly line extends from Arnos Grove to Cockfosters.[8]

- Piccadilly line extends over District line from Acton Town to Hounslow West and from South Harrow to Uxbridge. District line service withdrawn between Acton Town and Uxbridge.[8]

- Underground Group and MR brought under common public control with the formation of the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB).[56] Lord Ashfield and Frank Pick, formerly chairman and managing director of the Underground Group, become the LPTB's chairman and vice chairman.[57]

- LPTB publishes Harry Beck's first design for the Tube Map.[58]

- 1935

- Brill Tramway closes.[8]

- LPTB announces the New Works Programme, a five-year plan to modernise and extend the Underground network and to take over and electrify a number of main line routes.[59]

- 1936

- Metropolitan line closes from Aylesbury to Verney Junction.[8]

- 1937

- The combined Hampstead tube and C&SLR routes are officially renamed the Northern line and the CLR is renamed the Central line.[60][61]

- 1938

- Collision of two trains between Embankment and Temple kills six and injures 45 due to an incorrectly wired signal control.[62]

- 1939

- Bakerloo line extends from Baker Street to Finchley Road and takes over Metropolitan line services to Stanmore.[8]

- Northern line extends from Archway to East Finchley.[8]

- LPTB suspends majority of New Works Programme following outbreak of Second World War.[63]

- District line ends excursion services to Southend-on-Sea.[8]

1940s

- 1940

- Northern line extends over former EH&LR route to High Barnet.[8]

- Metropolitan line services withdrawn between Latimer Road and Kensington Olympia following bomb damage at Uxbridge Road.[8][64]

- Londoners use the deep tube platforms as air-raid shelters in the London Blitz.[65] Hits by German bombs during this period kill passengers and shelterers at Charing Cross (7 killed), Bounds Green (19 killed), Balham (68 killed), Tottenham Court Road (1 killed) and Camden Town (1 killed).[64]

- Frank Pick retires from LPTB.[66]

- 1941

- Northern line extends over former EH&LR route to Mill Hill East.[8]

- Uncompleted new Northern line depot at Aldenham converted for the construction of Halifax bombers.[67]

- Plessey uses unopened Central line tunnels between Wanstead and Gants Hill as an underground factory.[68]

- A German bomb explodes at King's Cross St Pancras station killing two members of staff.[69]

- A German bomb explodes in the Central line ticket hall at Bank, killing 56 people.[70]

- 1943

- Overcrowding by members of the public entering the air-raid shelter at the unopened station at Bethnal Green causes the death of 173 people by crushing.[70]

- 1946

- Central line extends from Liverpool Street to Stratford.[8]

- 1947

- Central line extends from Stratford over former ECR and GNR routes to Woodford and Newbury Park and from North Acton over GWR route to Greenford.[8]

- Lord Ashfield retires from LPTB.[71]

- 1948

- The government nationalises all London Transport operations and the London Transport Executive (LTE) replaces LPTB.[72]

- Central line extends over former ECR and GNR routes to Roding Valley and Loughton and over GWR route to West Ruislip.[8]

- 1949

- Central line extends over former ECR route to Ongar.[8]

- Circle line appears on tube maps as a separate service for the first time.[8]

1950s

- 1950

- LTE abandons New Works Programme Northern line extension to Bushey Heath due to introduction of the Metropolitan Green Belt preventing development in the areas to be served.[73]

- 1953

- LTE abandons take-over of former EH&LR line between Mill Hill East and Edgware due to diminished expected passenger numbers and lack of funds.[74]

- A rear-end collision between two trains on the Central line between Stratford and Leyton kills 12 passengers.[75]

- 1955

- Aldenham depot opens as bus overhaul works.[76]

- 1956

- Parliament grants approval for the construction of the Victoria line.[77]

- 1957

- Electric tube trains replace steam-hauled shuttles between Epping and Ongar.[78]

- 1959

- District line spur between Acton Town and South Acton is closed.[8]

1960s

- 1960

- The last published underground map designed by Harry Beck is released.[79]

- Electric tube trains replace steam-hauled shuttles between Chalfont & Latimer and Chesham.[80]

- 1961

- Metropolitan line services withdrawn between Aylesbury and Amersham.[8]

- 1963

- London Transport Board (LTB) replaces LTE.[81]

- 1964

- District line services withdrawn between Acton Town and Hounslow West.[8]

- Northern City line services withdrawn between Drayton Park and Finsbury Park to allow the tunnels to be reused for the Victoria line.[82]

- Experimental automatic ticket gates installed at Stamford Brook, Chiswick Park and Ravenscourt Park stations.[81]

- World's first automatic trains brought into service on Central line between Hainault and Woodford to test Victoria line operating systems.[81]

- 1968

- Victoria line opens between Walthamstow Central and Warren Street.[8]

- 1969

- Victoria line extends to Victoria.[8]

1970s

- 1970

- Greater London Council (GLC) takes control of management of London Underground from London Transport Board controlling the Underground through a new London Transport Executive (LTE).[83]

- 1971

- Victoria line extends to Brixton.[8]

- London Underground withdraws last operational steam locomotives from service.[84]

- 1975

- Moorgate tube crash kills 43 when a southbound Northern line (Highbury Branch) train fails to stop and crashes into the headwall of the tunnel.[85]

- Piccadilly line extends from Hounslow West to Hatton Cross.[8]

- 1976

- Northern line (Highbury Branch) transfers to British Rail operation.[8]

- During a bombing campaign against the Underground, an Irish Republican Army (IRA) gunman detonates a bomb on a train and kills the driver and injures a bystander while trying to escape.[86]

- 1977

- Piccadilly line extends from Hatton Cross to Heathrow Terminals 1, 2, 3.[8]

- 1979

- Jubilee line opens between Baker Street and Charing Cross and takes over Bakerloo line service to Stanmore.[8]

1980s

- 1980

- London Transport Museum opens in Covent Garden.[87]

- 1981

- GLC introduces Fares Fair policy to reduce ticket prices by increasing London Transport subsidies from local rates.[88]

- 1982

- Fares Fair policy ends following legal challenge from Bromley London Borough Council, which does not have any Underground services.[88]

- Bakerloo line withdraws services between Stonebridge Park and Watford Junction.[8]

- 1983

- LTE introduces Travelcard and divides network into five fare zones.[89]

- 1984

- Bakerloo line restarts services between Stonebridge Park and Harrow & Wealdstone.[8]

- Fire at Oxford Circus guts the northbound Victoria line platform and damages adjacent northbound Bakerloo line platform.[90]

- London Regional Transport (LRT) replaces LTE, removing control of transport in London from the GLC.[90]

- 1985

- LRT establishes its wholly owned subsidiary, London Underground Limited, to manage the Underground.[90]

- 1986

- Piccadilly line opens Heathrow loop and Heathrow Terminal 4.[8]

- 1987

- Fire at King's Cross kills 31 people when a blaze breaks out in a Piccadilly line escalator.[91]

1990s

- 1990

- Hammersmith & City line appears on the Tube map independently of the Metropolitan line for the first time.[8]

- 1991

- Travelcard Zone 5 split to create a new Travelcard Zone 6.[89]

- 1994

- Waterloo & City line transfers from British Rail to London Underground ownership.[8]

- Piccadilly line's Aldwych branch closes.[8]

- Central line's Epping to Ongar section closes.[8]

- 1995

- East London line closes for repairs to Thames Tunnel.[8]

- 1998

- East London line reopens.[8]

- 1999

- Jubilee line extends from Green Park to Stratford. The section from Green Park to Charing Cross closes.[8]

2000s

- 2000

- Last service operates with a train guard.[92]

- Transport for London (TfL), an executive body of the Greater London Authority, is established to take over responsibility for London's transport from LRT.[93] London Underground Limited moves to direct control by the Department for Transport.[94]

- 2002

- Lots Road Power Station closes.[95]

- 2003

- TfL takes control of London Underground Limited from the Department for Transport.[94]

- Oyster card smart card ticket system begins operation.[95]

- Public Private Partnership infrastructure companies Metronet and Tube Lines take over responsibility for maintenance of underground system.[96][97] Train operations remain the responsibility of TfL.

- A Central line train derails at Chancery Lane when a motor falls from the underside of a carriage.[98] Following investigations, modifications are made to all 1992 stock trains.

- 2005

- Suicide bombers detonate bombs on three tube trains and one bus, killing 52 and injuring more than 770.[99] Two weeks later four further bombers fail when their bombs do not explode.[100]

- 2006

- East London line closes from Shoreditch to Whitechapel.[101]

- 2007

- East London line closes completely for conversion into part of London Overground network.[102]

- Metronet goes into administration following failures to manage the costs and programmes of its projects. TfL takes over control.[103]

- 2008

- Piccadilly line extends to Heathrow Terminal 5.[104]

- Wood Lane station opens.[105]

- 2009

- Construction begins on Crossrail.[106]

- Circle line extends to Hammersmith.[107]

2010s

- 2010

- East London line reopens as part of London Overground network.[108]

- TfL takes over Tube Lines.[109]

- 2016

- All-night Night Tube services begin operating on sections of some lines on Fridays and Saturdays.[110]

- 2017

- Construction begins on the Northern line extension from Kennington to Battersea Power station.[111]

See also

- History of the London Underground

- List of London Underground stations

- List of former and unopened London Underground stations

Notes

- ^ Day & Reed 2008, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d Day & Reed 2008, p. 37.

- ^ Wolmar 2004, p. 8.

- ^ "No. 21581". The London Gazette. 11 August 1854. pp. 2465–2466.

- ^ a b Powell, W R, ed. (1966). "Economic influences on growth: Local transport". A History of the County of Essex. Vol. 5. pp. 21–29. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ "No. 22411". The London Gazette. 7 August 1860. pp. 2934–2935.

- ^ "No. 22632". The London Gazette. 6 June 1862. p. 2902.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj ck cl cm cn co cp cq cr cs ct cu cv cw cx cy cz da db dc dd de df Rose 1999.

- ^ Day & Reed 2008, p. 20.

- ^ "No. 22881". The London Gazette. 2 August 1863. pp. 3828–3830.

- ^ a b Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 10.

- ^ Beard 2002, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Day & Reed 2008, p. 32.

- ^ Baker, T.F.T.; Elrington, C.R., eds. (1982). "Chiswick: Communications". A History of the County of Middlesex. Vol. 7. pp. 51–54. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ Wolmar 2004, pp. 131–132.

- ^ a b Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Baker, T.F.T.; Elrington, C.R., eds. (1980). "Friern Barnet: Introduction". A History of the County of Middlesex. Vol. 6. pp. 6–15. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ Baker, T.F.T.; Elrington, C.R., eds. (1980). "Hornsey, including Highgate: Communications". A History of the County of Middlesex. Vol. 6. pp. 103–107. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ a b Day & Reed 2008, p. 27.

- ^ "No. 25382". The London Gazette. 29 July 1884. p. 3426.

- ^ "No. 26074". The London Gazette. 29 July 1890. p. 4170.

- ^ "No. 26190". The London Gazette. 7 August 1891. p. 4245.

- ^ "No. 26303". The London Gazette. 1 July 1892. pp. 3810–3811.

- ^ "No. 26435". The London Gazette. 25 August 1893. p. 4825.

- ^ "No. 26387". The London Gazette. 31 March 1893. p. 1987.

- ^ a b "No. 26881". The London Gazette. 10 August 1897. pp. 4481–4483.

- ^ "The Explosion on the Metropolitan Railway". The Times. No. 35189. 28 April 1897. p. 12. Retrieved 11 August 2009.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 113.

- ^ "No. 26984". The London Gazette. 5 July 1898. p. 4064.

- ^ "No. 27105". The London Gazette. 4 September 1899. pp. 4833–4834.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 94.

- ^ a b Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 114.

- ^ a b c Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 118.

- ^ "No. 27497". The London Gazette. 21 November 1902. p. 7533.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 213.

- ^ Beard 2002, p. 11.

- ^ Beard 2002, p. 10.

- ^ Powell, W R, ed. (1966). "The ancient parish of Barking: Introduction". A History of the County of Essex. Vol. 5. pp. 184–190. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ Day & Reed 2008, p. 64.

- ^ a b c Wolmar 2004, pp. 121–126.

- ^ a b Barker 2004 (1).

- ^ Irving, R. J. (2008). "Gibb, Sir George Stegmann (1850-1925)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/45711. Retrieved 30 April 2011. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Elliot 2004.

- ^ a b Barker 2004 (2).

- ^ Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 282–283.

- ^ a b "History of the roundel". London Transport Museum. 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ Day & Reed 2008, p. 79.

- ^ "No. 28311". The London Gazette. 23 November 1909. pp. 8816–8818.

- ^ Wolmar 2004, p. 182.

- ^ a b Wolmar 2004, p. 205.

- ^ a b Day & Reed 2008, p. 84.

- ^ "New Chairman of the Underground". The Times. No. 40858. 19 May 1915. p. 13. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ "Font Designer – Edward Johnston". The Source of the Originals. Linotype. 4 May 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ Beard 2002, p. 14.

- ^ Wolmar 2004, p. 269.

- ^ Day & Reed 2008, p. 112.

- ^ Wolmar 2004, p. 255.

- ^ Day & Reed 2008, p. 103.

- ^ Day & Reed 2008, p. 118.

- ^ Day & Reed 2008, p. 124.

- ^ "London Tubes' New Names - Northern And Central Lines". The Times. No. 47772. 25 August 1937. p. 12. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ^ Woodhouse 1938, p. 1.

- ^ Day & Reed 2008, p. 136.

- ^ a b Day & Reed 2008, p. 138.

- ^ Wolmar 2004, pp. 285–286.

- ^ "Mr Frank Pick to Retire". The Times. No. 48583. 6 April 1940. p. 8. Retrieved 29 April 2011.(subscription required)

- ^ Beard 2002, pp. 102–117.

- ^ Emmerson & Beard 2004, pp. 108–121.

- ^ Croome 2003,p. 56.

- ^ a b Wolmar 2004, p. 288–289

- ^ "L.P.T.B. Chairmanship". The Times. No. 50908. 3 November 1947. p. 4. Retrieved 11 August 2009.

- ^ Day & Reed 2008, p. 150.

- ^ Day & Reed 2008, p. 154.

- ^ Beard 2002, p. 127.

- ^ McMullen 1953, p. 1.

- ^ "The Aldenham Works soon after opening - photograph". Exploring 20th Century London. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2009.

- ^ Day & Reed 2008, p. 155.

- ^ Day & Reed 2008, p. 151.

- ^ "1960". A History of the London Tube Maps. Archived from the original on 15 August 2007. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ^ Day & Reed 2008, p. 157.

- ^ a b c Day & Reed 2008, p. 163.

- ^ Day & Reed 2008, p. 164.

- ^ Roberts, Frank; Baily, Michael (22 October 1969). "GLC to get transport free of £250m debt". The Times. No. 57697. p. 2. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- ^ Day & Reed 2008, p. 167.

- ^ McNaughton 1976, p. 2.

- ^ "On This Day: 15 March 1976 — Tube driver shot dead". BBC News. 2007. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- ^ Mullins, Sam (9 March 2020). "Shaping London Since 1980". London Transport Museum. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ a b Wolmar 2004, pp. 303–304.

- ^ a b Monopolies and Mergers Commission (1991). "London Underground Limited: A report on passenger and other services supplied by the company" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2009.

- ^ a b c Day & Reed 2008, p. 189.

- ^ Fennell 1988, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Day & Reed 2008, p. 207.

- ^ Waugh, Paul (3 July 2000). "The capital's new authority takes control today". The Independent. p. 8.

- ^ a b "London Underground Factsheet" (PDF). Transport for London. August 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ^ a b Day & Reed 2008, p. 218.

- ^ Webster, Ben (9 January 2003). "Tube consortium to earn £250m over six years". The Times. London. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- ^ Webster, Ben (5 April 2003). "Metronet seals £17bn Tube deal". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- ^ HM Railway Inspectorate 2006, p. 1.

- ^ "7 July Bombings: Overview". BBC News. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2009.

- ^ "21 July Attacks: Overview". BBC News. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2009.

- ^ "Closure of Shoreditch Station" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2009.

- ^ "The East London line extension" (PDF). Transport for London. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ^ "Metronet calls in administrators". BBC News. 18 July 2007. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- ^ "First Piccadilly line passengers travel to Heathrow Terminal 5". Transport for London. 27 March 2008. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ "New Wood Lane Underground Station". Transport for London. 14 October 2008. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ "Construction of Crossrail begins as foundations laid for new Canary Wharf station". Crossrail. 15 May 2009. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ "Find out more about the Circle line extension". Transport for London. 23 November 2009. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012. Retrieved 14 December 2009.

- ^ "East London Line officially opened by Boris Johnson". BBC News. 27 April 2010. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ "Tube maintenance back 'in house' as new deal is signed". BBC News. 8 May 2010. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ "Night Tube begins in London, bringing 'huge boost' to capital". BBC News. 20 August 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ^ "Tunnelling starts to extend the Northern line to Battersea". Transport for London. 11 April 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

References

- Badsey-Ellis, Antony (2005). London's Lost Tube Schemes. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-293-3.

- Barker, Theo (2004). "Speyer, Sir Edgar, baronet (1862–1932)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36215. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- Barker, Theo (2004). "Albert Henry Stanley (1874–1948)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36241. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- Beard, Tony (2002). By Tube Beyond Edgware. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-246-1.

- Croome, Desmond F. (2003). The Circle line - An Illustrated History. Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-267-2.

- Day, John R; Reed, John (2008) [1963]. The Story of London's Underground. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-316-6.

- Elliot, John; Robbins, Michael (2004). "Pick, Frank (1878–1941)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35522. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- Emmerson, Andrew; Beard, Tony (2004). London's Secret Tubes: London's wartime citadels, subways and shelters uncovered. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-283-6.

- Fennell, Desmond (1988). Investigation into the King's Cross Underground Fire (PDF). Department of Transport. ISBN 0-10-104992-7. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- HM Railway Inspectorate (2006). Derailment at Chancery Lane, 25 January 2003 (PDF). Health & Safery Executive. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- McMullen, D (1953). Report on the Collision which occurred on 8th April 1953 near Stratford on the Central Line (PDF). Ministry of Transport. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- McNaughton, Lt Col I K A (1976). Report on the Accident on 28th February 1975 at Moorgate Station (PDF). Department of the Environment. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- Rose, Douglas (1999) [1980]. The London Underground, A Diagrammatic History. Douglas Rose/Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-219-4.

- Wolmar, Christian (2004). The Subterranean Railway: How the London Underground Was Built and How It Changed the City Forever. Atlantic Books. ISBN 1-84354-023-1.

- Woodhouse, Lt Col E (1938). Accident near Charing Cross (PDF). Ministry of Transport. Retrieved 23 August 2009.