Bulat Okudzhava

Bulat Okudzhava | |

|---|---|

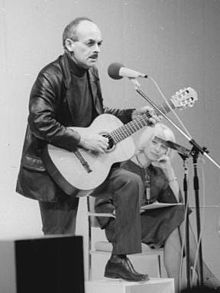

Okudzhava performing at Palace of the Republic, Berlin, Germany, 1976 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Bulat Shalvovich Okudzhava |

| Born | May 9, 1924 Moscow, Soviet Union |

| Origin | Soviet Union |

| Died | June 12, 1997 (aged 73) Paris, France |

| Genres | Author song |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, poet, editor, novelist, short story writer |

| Instrument(s) | Vocals, guitar |

| Years active | 1950s–1997 |

Bulat Shalvovich Okudzhava (Template:Lang-ru; Georgian: ბულატ ოკუჯავა) (May 9, 1924 – June 12, 1997) was a Soviet poet, writer, musician, novelist, and singer-songwriter of Georgian-Armenian ancestry. He was one of the founders of the Soviet genre called "author song" (авторская песня, avtorskaya pesnya), or "guitar song", and the author of about 200 songs, set to his own poetry. His songs are a mixture of Russian poetic and folksong traditions and the French chansonnier style represented by such contemporaries of Okudzhava as Georges Brassens. Though his songs were never overtly political (in contrast to those of some of his fellow Soviet bards), the freshness and independence of Okudzhava's artistic voice presented a subtle challenge to Soviet cultural authorities, who were thus hesitant for many years to give official recognition to Okudzhava.[citation needed]

Life

Bulat Okudzhava was born in Moscow on May 9, 1924 into a family of communists who had come from Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, to study and to work for the Communist Party. The son of a Georgian father, Shalva Okudzhava, and an Armenian mother, Ashkhen Nalbandyan, Bulat Okudzhava spoke and wrote only in Russian. Okudzava's mother was the niece of a well-known Armenian poet, Vahan Terian. His father served as a political commissar during the Civil War and as a high-ranking Communist Party member under the protection of Sergo Ordzhonikidze later on. His uncle Vladimir Okudzhava was an anarchist and a terrorist who left The Russian Empire after a failed attempt to assassinate the Kutaisi governor.[1] He was listed among the passengers of the infamous sealed train that delivered Vladimir Lenin, Grigory Zinoviev and other revolutionary leaders from Switzerland to Russia in 1917.[2]

Shalva Okudzhava was arrested in 1937 during the Great Purge, accused of trotskyism and wrecking and executed shortly after, along with his two brothers. His wife was also arrested in 1939 «for anti-Soviet deeds» and sent to a labor camp of Gulag. Bulat returned to Tbilisi to live with his relatives. His mother was released in 1946, but arrested for the second time in 1949, spending another 5 years in labor camps. She was fully released in 1954 and rehabilitated in 1956, along with her husband.[3]

In 1941, at the age of 17, one year before his scheduled school graduation, he volunteered for the Red Army infantry, and from 1942 he participated in the war with Nazi Germany. With the end of the Second World War, after his discharge from the service in 1945, he returned to Tbilisi where he passed his high school graduation exams and enrolled at Tbilisi State University, graduating in 1950. After graduating, he worked as a teacher, first in a rural school in the village of Shamordino in Kaluga district, and later in the city of Kaluga itself.

In 1956, three years after the death of Joseph Stalin, Okudzhava returned to Moscow, where he worked first as an editor in the publishing house "Young Guard," and later as the head of the poetry division at the most prominent national literary weekly in the former USSR, Literaturnaya Gazeta ("Literary Newspaper"). It was then, in the middle of the 1950s, that he began to compose songs and to perform them, accompanying himself on a Russian guitar.

Soon he was giving concerts. He only employed a few chords and had no formal training in music, but he possessed an exceptional melodic gift, and the intelligent lyrics of his songs blended perfectly with his music and his voice.[citation needed] His songs were praised by his friends, and amateur recordings were made. These unofficial recordings were widely copied as magnitizdat, and spread across the USSR and Poland, where other young people picked up guitars and started singing the songs for themselves. In 1969, his lyrics appeared in the classic Soviet film White Sun of the Desert.

Though Okudzhava's songs were not published by any official media organization until the late 1970s, they quickly achieved enormous popularity, especially among the intelligentsia – mainly in the USSR at first, but soon among Russian-speakers in other countries as well.[citation needed] Vladimir Nabokov, for example, cited his Sentimental March in the novel Ada or Ardor.

Okudzhava, however, regarded himself primarily as a poet and claimed that his musical recordings were insignificant. During the 1980s, he also published a great deal of prose (his novel The Show is Over won him the Russian Booker Prize in 1994). By the 1980s, recordings of Okudzhava performing his songs finally began to be officially released in the Soviet Union, and many volumes of his poetry were also published. In 1991, he was awarded the USSR State Prize. He supported the reform movement in the USSR and in October 1993, signed the Letter of Forty-Two.[4]

Okudzhava died in Paris on June 12, 1997, and is buried in the Vagankovo Cemetery in Moscow. A monument marks the building at 43 Arbat Street where he lived. His dacha in Peredelkino is now a museum that is open to the public.

A minor planet, 3149 Okudzhava, discovered by Czech astronomer Zdeňka Vávrová in 1981 is named after him.[5] His songs remain very popular and frequently performed.[6][7][8][9] They are also used for teaching Russian.[10]

When, like a beast, the snow storm roars,

when, in a rage, it howls,

You do not have to lock the doors,

of your residing house.

When on a lasting trip you go

the road is hard, supposing,

you ought to open wide your door;

leave it unlocked, don't close it.

As you leave home one quiet night,

decide, don't pause a minute:

mix up the burning pinewood light

with that of human spirit.

I wish the house you live in,

were always warm and faultless.

A closed door isn't worth a thing,

a lock is just as worthless.

Music

Okudzhava, like most bards, did not come from a musical background. He learned basic guitar skills with the help of some friends. He also knew how to play basic chords on a piano.

Okudzhava tuned his Russian guitar to the "Russian tuning" of D'-G'-C-D-g-b-d' (thickest to thinnest string), and often lowered it by one or two tones to better accommodate his voice. He played in a classical manner, usually finger picking the strings in an ascending/descending arpeggio or waltz pattern, with an alternating bass line picked by the thumb.

Initially Okudzhava was taught three basic chords, and towards the end of his life he claimed to know a total of seven.

Many of Okudzhava's songs are in the key of C minor (with downtuning B flat or A minor), centering on the C minor chord (X00X011, thickest to thinnest string), then progressing to a D 7 (00X0433), then either an E-flat minor (X55X566) or C major (55X5555). In addition to the aforementioned chords, the E-flat major chord (X55X567) was often featured in songs in a major key, usually C major (with downtuning B-flat or A major).

By the nineties, Okudzhava adopted the increasingly popular six string guitar but retained the Russian tuning, subtracting the fourth string, which was convenient to his style of playing.

Fiction in English translation

- The Art of Needles and Sins, (story), from The New Soviet Fiction, Abbeville Press, NY, 1989.

- Good-bye, Schoolboy! and Promoxys, (stories), from Fifty Years of Russian Prose, Volume 2, M.I.T Press, MA, 1971.

- The Extraordinary Adventures of Secret Agent Shipov in Pursuit of Count Leo Tolstoy, in the year 1862, (novel), Abelard-Schuman, UK, 1973.

- Nocturne: From the Notes of Lt. Amiran Amilakhvari, Retired, (novel), Harper and Row, NY, 1978.

- A Taste of Liberty, (novel), Ardis Publishers, 1986.

- Girl of My Dreams, (story), from 50 Writers: An Anthology of 20th Century Russian Short Stories, Academic Studies Press, 2011.

Selected discography

- Wonderful waltz, 1969

- While the world is still turning, 1994

- And when the first love comes... (А как первая любовь), 1997

- Piosenki (Songs), Polish edition, 2000

- Green lantern, On Smolensk road, Main song, Record on stone, and Your Honor – records made during last years of his life

References

- ^ Bulat Okudzhava (2006). The Abolished Theater: A Family Chronicle. Moscow: Zebra E, 336 pages. ISBN 978-5-94663-332-1

- ^ List of Passengers That Crossed Germany During the War published by Vladimir Burtsev on October, 1917 (in Russian)

- ^ Dmitry Bykov, Bulat Okudzhava. Moscow: Molodaya Gvardiya, 2009, 784 pages. ISBN 978-5-235-03255-2

- ^ Писатели требуют от правительства решительных действий. Izvestia (in Russian). October 5, 1993. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- ^ Dictionary of Minor Planet Names – p.260

- ^ Sentries of Love, Bulat Okudzhava's songs by Tatiana and Sergei Nikitin

- ^ Songs of Bulat Okudzhava by Galina Khomchik

- ^ Songs of Bulat Okudzhava by Zhanna Bichevskaya

- ^ Blue balloon, song and music by Bulat Okudzhava, performed by Elena Frolova

- ^ Tumanov, Vladimir. "Usings Songs in the Foreign Language Classroom." Russian Language Journal 54 (177–179) 2000: 13–33 (with Jeff Tennant).

External links

- English translations by M. Tubinshlak

- Audio files of his most famous songs in MP3 format

- Biography (www.russia-in-us.com)

- Biography (www.russia-ic.com)

- English translations by Alec Vagapov (55 songs)

- Russian poets of the 1960s

- English translations by Yevgeny Bonver (24 songs)

- Template:En icon Template:Ru icon English translations by Maya Jouravel (3 songs)

- Template:En icon Template:Ru icon The song of an open door

- Template:En icon Template:Ru icon On Volodya Vysotsky

- Okudzhava's short story Unexpected Joy

- Template:Ru icon Song Lyrics (100+ songs)

- Template:Ru icon Bulat Okudzhava – videp

- Template:Ru icon Rare photos of Bulat Okudzhava by Mihail Pazij

- 1924 births

- 1997 deaths

- Musicians from Moscow

- Singers from Moscow

- Burials at Vagankovo Cemetery

- Communist Party of the Soviet Union members

- Russian people of Georgian descent

- Russian bards

- Russian novelists

- Russian male novelists

- Russian people of Armenian descent

- Russian poets

- Russian male poets

- Seven-string guitarists

- Soviet poets

- Soviet novelists

- Soviet male writers

- Soviet songwriters

- Russian short story writers

- Soviet short story writers

- Russian Booker Prize winners

- Writers from Moscow

- Russian male singer-songwriters

- Soviet male singer-songwriters

- Tbilisi State University alumni

- Struga Poetry Evenings Golden Wreath laureates

- Russian male short story writers

- Soviet dissidents