Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot | |

|---|---|

Diderot, by Louis-Michel van Loo, 1767. | |

| Born | 5 October 1713 Langres, Champagne, France |

| Died | 31 July 1784 (aged 70) Paris, France |

| Era | 18th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Encyclopédistes |

Main interests | Science, Literature, Philosophy, and Art [1] |

| Signature | |

| |

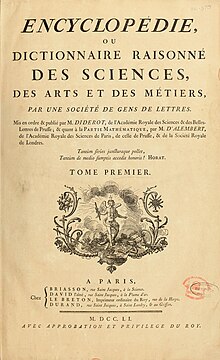

Denis Diderot (French: [dəni did(ə)ʁo]; 5 October 1713 – 31 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer. He was a prominent figure during the Enlightenment and is best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the Encyclopédie along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert.

Diderot's literary reputation during his lifetime rested primarily on his plays and his contributions to the Encyclopédie; many of his most important works, including Jacques the Fatalist, Rameau's Nephew, and D'Alembert's Dream, were published only after his death.[2][3]

Biography

Denis Diderot was born in Langres, Champagne, and began his formal education at a Jesuit collège in Langres.

His parents were Didier Diderot (1685–1759) a cutler, maître coutelier, and his wife Angélique Vigneron (1677–1748). Three of five siblings survived to adulthood, Denise Diderot (1715–97) and their youngest brother Pierre-Didier Diderot (1722–87), and finally their sister Angélique Diderot (1720–49). According to Arthur McCandless Wilson, Denis Diderot greatly admired his sister Denise, sometimes referring to her as "a female Socrates".[4]

In 1732 Denis Diderot earned the Master of Arts degree in philosophy. Then he entered the Collège d'Harcourt in Paris. He abandoned the idea of entering the clergy and decided instead to study law. His study of law was short-lived however and in 1734 Diderot decided to become a writer. Because of his refusal to enter one of the learned professions, he was disowned by his father, and for the next ten years he lived a bohemian existence.[5]

In 1742 he befriended Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In 1743 he further alienated his father by marrying Antoinette Champion (1710–96), a devout Roman Catholic. The match was considered inappropriate due to Champion's low social standing, poor education, fatherless status, and lack of a dowry. She was about three years older than Diderot. The marriage in October 1743 produced one surviving child, a girl. Her name was Angélique, after both Diderot's dead mother and sister. The death of his sister, a nun, from overwork in the convent may have affected Diderot's opinion of religion. She is assumed to have been the inspiration for his novel about a nun, La Religieuse, in which he depicts a woman who is forced to enter a convent where she suffers at the hands of the other nuns in the community.[5]

Diderot had affairs with Mlle. Babuti (who would marry Greuze), Madeleine de Puisieux, Sophie Volland, and Mme de Maux.[6] His letters to Sophie Volland are known for their candor and are regarded to be "among the literary treasures of the eighteenth century." [7]

Though his work was broad as well as rigorous, it did not bring Diderot riches. He secured none of the posts that were occasionally given to needy men of letters; he could not even obtain the bare official recognition of merit which was implied by being chosen a member of the Académie française. When the time came for him to provide a dowry for his daughter, he saw no alternative than to sell his library. When Empress Catherine II of Russia heard of his financial troubles she commissioned an agent in Paris to buy the library. She then requested that the philosopher retain the books in Paris until she required them, and act as her librarian with a yearly salary.[8] Between October 1773 and March 1774, the sick Diderot spent a few months at the empress's court in Saint Petersburg.[5][9]

Diderot died of pulmonary thrombosis in Paris on 31 July 1784, and was buried in the city's Église Saint-Roch. His heirs sent his vast library to Catherine II, who had it deposited at the National Library of Russia. He has several times been denied burial in the Panthéon with other French notables,[10] but the French government did recently announce the possibility of memorializing him in this fashion, on the 300th anniversary of his birth (October 2013). For the moment, however, this idea seems to have been tabled.[11]

Early works

Diderot's earliest works included a translation of Temple Stanyan's History of Greece (1743); with two colleagues, François-Vincent Toussaint and Marc-Antoine Eidous, he produced a translation of Robert James's Medicinal Dictionary(1746–1748).[12] In 1745, he published a translation of Shaftesbury's Inquiry Concerning Virtue and Merit, to which he had added his own "reflections".[13]

Philosophical Thoughts

In 1746, Diderot wrote his first original work: the Philosophical Thoughts (French:Pensées philosophiques).[14][15] In this book, Diderot argued for a reconciliation of reason with feeling so as to establish harmony. According to Diderot, without feeling there would be a detrimental effect on virtue and no possibility of creating sublime work. However, since feeling without discipline can be destructive, reason was necessary to rein in feeling.[13]

At the time Diderot wrote this book he was a deist. Hence there is a defense of deism in this book, and some arguments against atheism.[13] The book also contains criticism of Christianity.[16]

The Skeptic's Walk

In 1747, Diderot wrote the The Skeptic's Walk (French:Promenade du sceptique)[17] in which a deist, an atheist, and a pantheist have a dialogue on the nature of divinity. The deist gives the argument from design. The atheist says that the universe is better explained by physics, chemistry, matter, and motion. The pantheist says that the cosmic unity of mind and matter, which are co-eternal and comprise the universe, is God. This work remained unpublished till 1830 since the local police—warned by the priests of another attack on Christianity—either seized the manuscript or made Diderot give an undertaking that he would not publish this work according to different versions of what happened.[16]

The Indiscreet Jewels

In 1748 Diderot found the need to raise money at short notice. He had become a father through his wife, and his mistress Mme. de Puisieux was making financial demands from him. At this time, Diderot had stated to Mme. de Puisieux that writing a novel was a trivial task, whereupon she had challenged his comment. In response, Diderot wrote his novel The Indiscreet Jewels (French:Les Bijoux Indiscrets). The book is about the magical ring of a Sultan which induces any woman's "discreet jewels"[18][note 1]to confess their sexual experiences when the ring is pointed at them.[19] In all, the ring is pointed at thirty different women in the book—usually at a dinner or a social meeting—with the Sultan typically being visible to the woman.[20][21] However, since the ring has the additional property of making its owner invisible when required, a few of the sexual experiences recounted are through direct observation with the Sultan making himself invisible and placing his person in the unsuspecting woman's boudoir.[20]

Besides the bawdiness there are several digressions into philosophy, music, and literature in the book. In one such philosophical digression, the Sultan has a dream in which he sees a child named "Experiment" growing bigger and stronger till it demolishes an ancient temple named "Hypothesis".The book proved to be lucrative for Diderot even though it could only be sold clandestinely. It is Diderot's most published work.[21]

The book is believed to be an imitation of Le Sopha.[21]

Scientific work

All his life Diderot would keep writing on science in a desultory way. The scientific work of which he himself was most proud of was the Memoires sur differents sujets de mathematique (1748) which contains original ideas on acoustics, tension, air resistance, and "a project for a new organ" which could be played by all. Some of Diderot's scientific works were applauded by contemporary publications of his time like The Gentleman's Magazine, the Journal des savants; and the Jesuit publication Journal de Trevoux which invited more such work "on the part of a man as clever and able as M. Diderot seems to be, of whom we should also observe that his style is as elegant, trenchant, and unaffected as it is lively and ingenious."[21]

Letter on the Blind

Diderot's celebrated Letter on the Blind (Lettre sur les aveugles à l'usage de ceux qui voient) (1749) introduced him to the world as an original thinker.[22] The subject is a discussion of the interrelation between man's reason and the knowledge acquired through perception (the five senses). The title of his book also evoked some ironic doubt about who exactly were "the blind" under discussion. In the essay, blind English mathematician Nicholas Saunderson[23] argues that, since knowledge derives from the senses, mathematics is the only form of knowledge that both he and a sighted person can agree on. It is suggested that the blind could be taught to read through their sense of touch (a later essay, Lettre sur les sourds et muets, considered the case of a similar deprivation in the deaf and mute). According to Jonathan Israel, what makes the Lettre sur les aveugles so remarkable, however, is its distinct, if undeveloped, presentation of the theory of variation and natural selection.[24]

This powerful essay, for which La Mettrie expressed warm appreciation in 1751, revolves around a remarkable deathbed scene in which a dying blind philosopher, Saunderson, rejects the arguments of a deist clergyman who endeavours to win him round to a belief in a providential God during his last hours. Saunderson's arguments are those of a neo-Spinozist Naturalist and fatalist, using a sophisticated notion of the self-generation and natural evolution of species without Creation or supernatural intervention. The notion of "thinking matter" is upheld and the "argument from design" discarded (following La Mettrie) as hollow and unconvincing. The work appeared anonymously in Paris in June 1749, and was vigorously suppressed by the authorities. Diderot, who had been under police surveillance since 1747, was swiftly identified as the author, had his manuscripts confiscated, and was imprisoned for some months, under a lettre de cachet, on the outskirts of Paris, in the dungeons at Vincennes where he was visited almost daily by Rousseau, at the time his closest and most assiduous ally.[25]

Voltaire wrote an enthusiastic letter to Diderot commending the Lettre and stating that he had held Diderot in high regard for a long time to which Diderot had sent a warm response. Soon after this, Diderot was arrested.[26]

Science historian Conway Zirkle has written that Diderot was an early evolutionary thinker and noted that his passage that described natural selection was "so clear and accurate that it almost seems that we would be forced to accept his conclusions as a logical necessity even in the absence of the evidence collected since his time."[27]

Incarceration and release

Angered by public resentment of the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle, the government started incarcerating many of its critics. It was decided at this time to rein in Diderot. On 23 July 1749, the governor of the Vincennes fortress instructed the police to incarcerate Diderot in the Vincennes. The next day he was arrested and placed in solitary confinement in the Vincennes. He had been permitted to retain one book which he had in his possession at the time of his arrest. This was Paradise Lost; he read this book during his incarceration, and wrote notes and annotations on the book, using a toothpick as pen, and ink that he made by scraping slate from the walls and mixing it with wine.[28]

In August 1749, Mme du Chatelet, presumably at Voltaire's behest, wrote to the governor of Vincennes, who was her kinsman, pleading that Diderot be lodged more comfortably while jailed. The governor then offered Diderot access to the great halls of the Vincennes castle and the freedom to receive books and visitors providing he would write a document of submission.[28] On 13 August 1749, Diderot wrote to the governor:

I admit to you...that the Pensees, the Bijoux, and the Lettre sur les aveugles are debaucheries of the mind that escaped from me; but I can...promise you on my honor (and I do have honor) that they will be the last, and that they are the only ones...As for those who have taken part in the publication of these works, nothing will be hidden from you. I shall depose verbally, in the depths[secrecy] of your heart, the names both of the publishers and the printers.[29]

On 20 August, Diderot was lodged in a comfortable room in the Vincennes, and allowed to meet visitors, and walk in the gardens of the Vincennes. On 23 August, Diderot signed another letter promising to never leave the Vincennes without permission.[29] On 3 November 1749, Diderot was released from the Vincennes.[30] Subsequently, in 1750, he released the prospectus for the Encyclopédie.[31]

Encyclopédie

Genesis

André Le Breton, a bookseller and printer, approached Diderot with a project for the publication of a translation of Ephraim Chambers' Cyclopaedia, or Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences into French, first undertaken by the Englishman John Mills, and followed by the German Gottfried Sellius.[8] Diderot accepted the proposal, and transformed it. He persuaded Le Breton to publish a new work, which would consolidate ideas and knowledge from the Republic of Letters. The publishers found capital for a larger enterprise than they had first planned. Jean le Rond d'Alembert was persuaded to become Diderot's colleague; and permission was procured from the government.

In 1750 an elaborate prospectus announced the project, and in 1751 the first volume was published.[8] This work was unorthodox and advanced for the time. Diderot stated that "An encyclopedia ought to make good the failure to execute such a project hitherto, and should encompass not only the fields already covered by the academies, but each and every branch of human knowledge." Comprehensive knowledge will give "the power to change men's common way of thinking."[32] The work combined scholarship with information on trades. Diderot emphasized the abundance of knowledge within each subject area. Everyone would benefit from these insights.

Controversies

Diderot's work, however, was mired in controversy from the beginning; the project was suspended by the courts in 1752. Just as the second volume was completed accusations arose, regarding seditious content, concerning the editor's entries on religion and natural law. Diderot was detained and his house was searched for manuscripts for subsequent articles. But the search proved fruitless as no manuscripts could be found. They were hidden in the house of an unlikely confederate–Chretien de Lamoignon Malesherbes, the very official who ordered the search. Although Malesherbes was a staunch absolutist—loyal to the monarchy—he was sympathetic to the literary project. Along with his support, and that of other well-placed influential confederates, the project resumed. Diderot returned to his efforts only to be constantly embroiled in controversy.

These twenty years were to Diderot not merely a time of incessant drudgery, but harassing persecution and desertion of friends. The ecclesiastical party detested the Encyclopédie, in which they saw a rising stronghold for their philosophic enemies. By 1757 they could endure it no longer. The subscribers had grown from 2,000 to 4,000, a measure of the growth of the work in popular influence and power.[8] The Encyclopédie threatened the governing social classes of France (aristocracy) because it took for granted the justice of religious tolerance, freedom of thought, and the value of science and industry.[33] It asserted the doctrine that the main concern of the nation's government ought to be the nation's common people. It was believed that the Encyclopédie was the work of an organized band of conspirators against society, and that the dangerous ideas they held were made truly formidable by their open publication. In 1759, the Encyclopédie was formally suppressed.[8] The decree did not stop the work, which went on, but its difficulties increased by the necessity of being clandestine. Jean le Rond d'Alembert withdrew from the enterprise and other powerful colleagues, including Anne Robert Jacques Turgot, Baron de Laune, declined to contribute further to a book which had acquired a bad reputation.[22]

Diderot's contribution

Diderot was left to finish the task as best he could. He wrote several hundred articles, some very slight, but many of them laborious, comprehensive, and long. He damaged his eyesight correcting proofs and editing the manuscripts of less competent contributors. He spent his days at workshops, mastering manufacturing processes, and his nights writing what he had learned during the day. He was incessantly harassed by threats of police raids. The last copies of the first volume were issued in 1765.

In 1764, when his immense work was drawing to an end, he encountered a crowning mortification: he discovered that the bookseller, Le Breton, fearing the government's displeasure, had struck out from the proof sheets, after they had left Diderot's hands, all passages that he considered too dangerous. "He and his printing-house overseer," writes Furbank, "had worked in complete secrecy, and had moreover deliberately destroyed the author's original manuscript so that the damage could not be repaired."[34] The monument to which Diderot had given the labor of twenty long and oppressive years was irreparably mutilated and defaced.[8] It was 12 years, in 1772, before the subscribers received the final 28 folio volumes of the Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers since the first volume had been published.

Mature works

Although the Encyclopédie was Diderot's most monumental product, he was the author of many other works that sowed nearly every intellectual field with new and creative ideas.[8] Diderot's writing ranges from a graceful trifle like the Regrets sur ma vieille robe de chambre (Regrets for my Old Dressing Gown) up to the heady D'Alembert's Dream (Le Rêve de d'Alembert) (composed 1769), a philosophical dialogue in which he plunges into the depths of the controversy as to the ultimate constitution of matter and the meaning of life.[8] Jacques le fataliste (written in 1773, but not published until 1792 in German and 1796 in French) is similar to Tristram Shandy and The Sentimental Journey in its challenge to the conventional novel's structure and content.[35]

Rameau's Nephew

The dialogue Rameau's Nephew (French: Le Neveu de Rameau) is a "farce-tragedy" reminiscent of the Satires of Horace, a favorite classical author of Diderot's whose lines "Vertumnis, quotquot sunt, natus iniquis" ("A man born when every single Vertumnus was out of sorts") appear as epigraph. According to Nicholas Cronk, Rameau's Nephew is "arguably the greatest work of the French Enlightenment's greatest writer."[36]

Diderot's intention in writing the dialogue—whether as a satire on contemporary manners, a reduction of the theory of self-interest to an absurdity, the application of irony to the ethics of ordinary convention, a mere setting for a discussion about music, or a vigorous dramatic sketch of a parasite and a human original—is disputed. In political terms it explores "the bipolarisation of the social classes under absolute monarchy," and insofar as its protagonist demonstrates how the servant often manipulates the master, Le Neveu de Rameau can be seen to anticipate Hegel's master-slave dialectic.[37]

The narrator in the book is Jean-François Rameau, nephew of the famous Jean-Philippe Rameau. The nephew composes and teaches music with some success but feels disadvantaged by his name and is jealous of his uncle. Eventually he sinks into an indolent and debauched state. After his wife's death, he loses all self-esteem and his brusque manners result in him being ostracized by former friends. A character profile of the nephew is now sketched by Diderot: a man who was once wealthy and comfortable with a pretty wife, who is now living in poverty and decadence, shunned by his friends. And yet this man retains enough of his past to analyze his despondency philosophically and maintains his sense of humor. Essentially he believes in nothing—not in religion, nor in morality; nor in the Roussean view about nature being better than civilization since in his opinion every species in nature consumes one another.[38] He views the same process at work in the economic world where men consume each other through the legal system.[39] The wise man, according to the nephew, will consequently practice hedonism:

Hurrah for wisdom and philosophy!--the wisdom of Solomon: to drink good wines, gorge on choice foods, tumble pretty women, sleep on downy beds; outside of that, all is vanity.[40]

The dialogue ends with Diderot calling the nephew a wastrel, a coward, and a glutton devoid of spiritual values to which the nephew replies: "I believe you are right."[40]

The publication history of the Nephew is circuitous. Written in 1761, Diderot never saw the work through to publication during his lifetime, and apparently did not even share it with his friends. After Diderot's death, a copy of the text reached Schiller who gave it to Goethe who, in 1805, translated the work into German.[22] Goethe's translation entered France, and was retranslated into French in 1821. Another copy of the text was published in 1823, but it had been expurgated by Diderot's daughter prior to publication. The original manuscript was only found in 1891.[41]

Visual Arts

Diderot's most intimate friend was the philologist Friedrich Melchior Grimm.[42] They were brought together by their friend in common at that time, Jean-Jacques Rousseau.[30] In 1753, Grimm began writing a newsletter, the La Correspondance littéraire, philosophique et critique, which he would send to various high personages in Europe.[43]

In 1759, Grimm asked Diderot to report on the biennial art exhibitions in the Louvre for the Correspondance. Diderot reported on the Salons between 1759 and 1771 and again in 1775 and 1781.[44] Diderot's reports would become "the most celebrated contributions to La Correspondance."[43]

According to Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve, Diderot's reports initiated the French into a new way of laughing, and introduced people to the mystery and purport of colour by ideas. "Before Diderot," Anne Louise Germaine de Staël wrote, "I had never seen anything in pictures except dull and lifeless colours; it was his imagination that gave them relief and life, and it is almost a new sense for which I am indebted to his genius."[8]

Diderot had appended an Essai sur la peinture to his report on the 1765 Salon in which he expressed his views on artistic beauty. Goethe described the Essai sur la peinture as "a magnificent work;it speaks even more usefully to the poet than to the painter, though for the painter too it is a torch of blazing illumination."[45]

Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725-1805) was Diderot's favorite contemporary artist.[46] Diderot appreciated Greuze's sentimentality, and more particularly Greuze's portrayals of his wife who had once been Diderot's mistress.[45]

Theatre

Diderot wrote sentimental plays, Le Fils naturel (1757) and Le Père de famille (1758), accompanying them with essays on theatrical theory and practice, including "Les Entretiens sur Le Fils Naturel" (Conversations on The Natural Son), in which he announced the principles of a new drama: the 'serious genre', a realistic midpoint between comedy and tragedy that stood in opposition to the stilted conventions of the classical French stage. Diderot introduced the concept of the fourth wall, the imaginary "wall" at the front of the stage in a traditional three-walled box set in a proscenium theatre, through which the audience sees the action in the world of the play.[47][48][49]

Diderot and Catherine the Great

Journey to Russia

When the Russian Empress Catherine the Great heard that Diderot was in need of money, she arranged to buy his library and appoint him caretaker of it until his death, at a salary of 1,000 livres per year. She even paid him 25 years salary in advance.[50] Although Diderot hated traveling,[51] he was obliged to visit her.[50]

On 9 October 1773, he reached St. Petersburg, met Catherine the next day and they had several discussions on various subjects. During his five-month stay at her court, he met her almost every day.[52] During these conversations, he would later state, they spoke 'man to man'.[50][note 2] He would occasionally make his point by slapping her thighs. In a letter to Madame Geoffrin, Catherine wrote:

Your Diderot is an extraordinary man. I emerge from interviews with him with my thighs bruised and quite black. I have been obliged to put a table between us to protect myself and my members.[50]

One of the topics discussed was Diderot's ideas about how to transform Russia into a utopia. In a letter to Comte de Ségur, the Empress wrote that if she had followed Diderot's advice, chaos would have ensued in her kingdom.[50]

Back in France

When returning, Diderot asked the Empress for 1,500 rubles as reimbursement for his trip. She gave him 3,000 rubles, an expensive ring, and an officer to escort him back to Paris. He would write a eulogy in her honor on reaching Paris.[54]

In July 1784, upon hearing that Diderot was in poor health, Catherine arranged for him to move into a luxurious suite in the Rue de Richelieu. Diderot died two weeks after moving there—on 31 July 1784.[55]

Among Diderot's last works were notes "On the Instructions of her Imperial Majesty...for the Drawing up of Laws". This commentary on Russia included replies to some arguments Catherine had made in the Nakaz.[54][56] Diderot wrote that Catherine was certainly despotic, due to circumstances and training, but was not inherently tyrannical. Thus, if she wished to destroy despotism in Russia, she should abdicate her throne and destroy anyone who tries to revive the monarchy.[56] She should publicly declare that "there is no true sovereign other than the nation, and there can be no true legislator other than the people."[57] She should create a new Russian legal code establishing an independent legal framework and starting with the text: "We the people, and we the sovereign of this people, swear conjointly these laws, by which we are judged equally."[57] In the Nakaz, Catherine had written: "It is for legislation to follow the spirit of the nation."[57] Diderot's rebuttal stated that it is for legislation to make the spirit of the nation. For instance, he argued, it is not appropriate to make public executions unnecessarily horrific.[58]

Ultimately, Diderot decided not to send these notes to Catherine; however, they were delivered to her with his other papers after he died. When she read them, she was furious and commented that they were an incoherent gibberish devoid of prudence, insight, and verisimilitude.[54][59]

Philosophy

In his youth, Diderot was originally a follower of Voltaire and his deist Anglomanie, but gradually moved away from this line of thought towards materialism and atheism, a move which was finally realised in 1747 in the philosophical debate in the second part of his The Skeptic's Walk (1747).[60] He was "a philosopher in whom all the contradictions of the time struggle with one another"(Rosenkranz).[22]

In his 1754 book On the interpretation of Nature, Diderot expounded on his views about Nature, evolution, materialism, mathematics, and experimental science.[61][62] It is speculated that Diderot may have contributed to his friend Baron d'Holbach's 1770 book The System of Nature.[22] Diderot had enthusiastically endorsed the book stating that:

What I like is a philosophy clear, definite, and frank, such as you have in the System of Nature. The author is not an atheist on one page and a deist on another. His philosophy is all of one piece.[63]

In conceiving the Encyclopedie, Diderot had thought of the work as a fight on behalf of posterity and had expressed confidence that posterity would be grateful for his effort. According to Diderot, "posterity is for the philosopher what the 'other world' is for the man of religion."[64]

Appreciation and influence

Marmontel and Henri Meister commented on the great pleasure of having intellectual conversations with Diderot.[65] Morellet, a regular attendee at D'Holbach's salon, wrote: "It is there that I heard...Diderot treat questions of philosophy, art, or literature, and by his wealth of expression, fluency, and inspired appearance, hold our attention for a long stretch of time."[66] Diderot's contemporary, and rival, Jean Jacques Rousseau wrote in his Confessions that after a few centuries Diderot would be accorded as much respect by posterity as was given to Plato and Aristotle.[65] In Germany, Goethe, Schiller, and Lessing[67] expressed admiration for Diderot's writings, Goethe pronouncing Diderot's Rameau's Nephew to be "the classical work of an outstanding man."[41]

In the next century, Diderot was admired by Balzac, Delacroix, Stendhal, Zola, and Schopenhauer.[68] According to Comte, Diderot was the foremost intellectual in an exciting age.[69] Historian Michelet described him as "the true Prometheus" and stated that Diderot's ideas would continue to remain influential long into the future. Marx chose Diderot as his "favourite prose-writer."[70]

Contemporary tributes

Otis Fellows and Norman Torrey have described Diderot as "the most interesting and provocative figure of the French eighteenth century."[71]

In 1993, American writer Cathleen Schine published Rameau's Niece, a satire of academic life in New York that took as its premise a woman's research into an (imagined) 18th-century pornographic parody of Diderot's Rameau's Nephew. The book was praised by Michiko Kakutani in the New York Times as "a nimble philosophical satire of the academic mind" and "an enchanting comedy of modern manners."[72]

French author Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt wrote a play titled Le Libertin (The Libertine) which imagines a day in Diderot's life including a fictional sitting for a woman painter which becomes sexually charged but is interrupted by the demands of editing the Encyclopédie.[73] It was first staged at Paris' Théâtre Montparnasse in 1997 starring Bernard Giraudeau as Diderot and Christiane Cohendy as Madame Therbouche and was well received by critics.[74]

In 2013, the tricentennial of Diderot's birth, his hometown of Langres held a series of events in his honor and produced an audio tour of the town highlighting places that were part of Diderot's past, including the remains of the convent where his sister Angélique took her vows.[75] On 6 October 2013, a museum of the Enlightenment focusing on Diderot's contributions to the movement, the Maison des Lumières Denis Diderot, was inaugurated in Langres.[76]

Bibliography

- Essai sur le mérite et la vertu, written by Shaftesbury French translation and annotation by Diderot (1745)

- Philosophical Thoughts, essay (1746)

- La Promenade du sceptique (1747)

- The Indiscreet Jewels, novel (1748)

- Lettre sur les aveugles à l'usage de ceux qui voient (1749)

- Encyclopédie, (1750–1765)

- Lettre sur les sourds et muets (1751)

- Pensées sur l'interprétation de la nature, essai (1751)

- "Systeme de la Nature," (1754)

- Le Fils naturel (1757)

- Entretiens sur le Fils naturel (1757)

- Le père de famille (1758)

- Discours sur la poesie dramatique (1758)

- Salons, critique d'art (1759–1781)

- La Religieuse, Roman (1760; revised in 1770 and in the early 1780s; the novel was first published as a volume posthumously in 1796).

- Le neveu de Rameau, dialogue (1763).[77]

- Lettre sur le commerce de la librairie (1763)

- Mystification ou l’histoire des portraits (1768)

- Entretien entre D'Alembert et Diderot (1769)

- Le rêve de D'Alembert, dialogue (1769)

- Suite de l'entretien entre D'Alembert et Diderot (1769)

- Paradoxe sur le comédien (written between 1770 and 1778; first published posthumously in 1830)

- Apologie de l'abbé Galiani (1770)

- Principes philosophiques sur la matière et le mouvement, essai (1770)

- Entretien d'un père avec ses enfants (1771)

- Jacques le fataliste et son maître, novel (1771–1778)

- Ceci n'est pas un conte, story (1772)

- Madame de La Carlière, short story and moral fable, (1772)

- Supplément au voyage de Bougainville (1772)

- Histoire philosophique et politique des deux Indes, in collaboration with Raynal (1772–1781)[78]

- Voyage en Hollande (1773)

- Éléments de physiologie (1773–1774)

- Réfutation d'Helvétius (1774)

- Observations sur le Nakaz (1774)

- Essai sur les règnes de Claude et de Néron (1778)

- Est-il Bon? Est-il méchant? (1781)

- Lettre apologétique de l'abbé Raynal à Monsieur Grimm (1781)

- Aux insurgents d'Amérique (1782)

See also

Notes

- ^ Bijou is a slang word meaning the vagina.[18]

- ^ Diderot later narrated the following conversation as having taken place:

Catherine:"You have a hot head, and I have one too. We interrupt each other, we do not hear what the other one says, and so we say stupid things." Diderot:"With this difference, that when I interrupt your Majesty, I commit a great impertinence."Catherine: "No,between men there is no such thing as impertinence."[53]

References

- ^ Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. p. 650.

- ^ Norman Hampson. The Enlightenment. 1968. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1982. p. 128

- ^ Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. pp. 678–9.

- ^ Arthur M. Wilson. Diderot: The Testing Years, 1713–1759. New York: Oxford University Press, 1957, p. 14 [1]

- ^ a b c Arthur Wilson, Diderot (New York: Oxford, 1972).

- ^ Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. pp. 675–6.

- ^ Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. p. 675.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Morley, John (1911). "Diderot, Denis". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 204–206.

- ^ http://blog.kb.nl/diderot-op-de-kneuterdijk-1

- ^ "In the Panthéon". Lapham's Quarterly. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ Curran, Andrew S. (24 January 2013). "Diderot, an American Exemplar? Bien Sûr!". New York Times. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ Mark Twain, "A Majestic Literary Fossil", originally from Harper's New Monthly Magazine, vol. 80, issue 477, pp. 439–44, February 1890. Online at Harper's site. Accessed 24 September 2006.

- ^ a b c Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. p. 625.

- ^ P.N. Furbank (1992). Diderot:A Critical Biography. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 27.

- ^ Bryan Magee. The Story of Philosophy. DK Publishing, Inc., New York: 1998. p. 124

- ^ a b Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. p. 626.

- ^ Otis Fellows (1977). Diderot. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 41.

- ^ a b P.N. Furbank (1992). Diderot:A Critical Biography. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 44.

- ^ Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. pp. 626–7.

- ^ a b Suzanne Rodin Pucci (1990). The Discreet Charms of the Exotic:Fictions of the harem in eighteenth-century France in Exoticism in the Enlightenment (ed. George Sebastian Rousseau and Roy Porter). Manchester University Press. p. 156.

- ^ a b c d Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. p. 627.

- ^ a b c d e Morley 1911.

- ^ Stephens, Mitchell (2014). Imagine there's no heaven: how atheism helped create the modern world. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 123–124. ISBN 9781137002600. OCLC 852658386. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ Diderot's contemporary, also a Frenchman, Pierre Louis Maupertuis–who in 1745 was named Head of the Prussian Academy of Science under Frederic the Great– was developing similar ideas. These proto-evolutionary theories were by no means as thought out and systematic as those of Charles Darwin a hundred years later.

- ^ Jonathan I. Israel, Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity 1650–1750. (Oxford University Press. 2001, 2002), p. 710

- ^ Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. pp. 629–30.

- ^ Zirkle, Conway (25 April 1941). "Natural Selection before the 'Origin of Species'". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 84 (1). Philadelphia, PA: American Philosophical Society: 71–123. ISSN 0003-049X. JSTOR 984852.

- ^ a b Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. p. 630.

- ^ a b Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. p. 631.

- ^ a b Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. p. 632.

- ^ Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. p. 633.

- ^ Examples are Diderot's articles on Asian philosophy and religion; see Urs App. The Birth of Orientalism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010 (ISBN 978-0-8122-4261-4), pp. 133–87.

- ^ Lyons, Martyn. "Books: A Living History". Getty Publishing, 2011, p 107.

- ^ P. N. Furbank. Diderot: A Critical Biography. New York: Knopf, 1992, p. 273.

- ^ Jacques Smietanski, Le Réalisme dans Jacques le Fataliste (Paris: Nizet, 1965); Will McMorran, The Inn and the Traveller: Digressive Topographies in the Early Modern European Novel (Oxford: Legenda, 2002).

- ^ Nicholas Cronk, "Introduction", in Rameau's Nephew and First Satire, Oxford: Oxford UP, 2006 (pp. vii-xxv), p. vii.

- ^ Jean Varloot, "Préface", in: Jean Varloot, ed. Le Neveu de Rameau et autres dialogues philosophiques, Paris: Gallimard, 1972 (pp. 9-28), p. 25-26.

- ^ Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. p. 660.

- ^ Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. pp. 660–1.

- ^ a b Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. p. 661.

- ^ a b Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. p. 659.

- ^ Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. p. 677.

- ^ a b Jacobs, Alan (11 February 2014). "Grimm's Heirs". The New Atlantis: A Journal of Technology and Society. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. pp. 666–7.

- ^ a b Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. p. 668.

- ^ Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, French Eighteenth-Century Painters. Cornell Paperbacks, 1981, pp. 222–25. ISBN 0-8014-9218-1

- ^ Bell, Elizabeth S. (2008). Theories of Performance. Los Angeles: Sage. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-4129-2637-9..

- ^ Wallis, Mick; Shepherd, Simon (1998). Studying plays. London: Arnold. p. 214. ISBN 0-340-73156-7..

- ^ Abelman, Robert (1998). Reaching a critical mass: a critical analysis of television entertainment. Mahwah, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates. pp. 8–11. ISBN 0-8058-2199-6..

- ^ a b c d e Will Durant (1967). The Story of Civilization Volume 10:Rousseau and Revolution. Simon&Schuster. p. 448.

- ^ Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. p. 674.

- ^ Will Durant (1967). The Story of Civilization Volume 10:Rousseau and Revolution. Simon&Schuster. pp. 448–9.

- ^ P.N. Furbank (1992). Diderot:A Critical Biography. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 379.

- ^ a b c Will Durant (1967). The Story of Civilization Volume 10:Rousseau and Revolution. Simon&Schuster. p. 449.

- ^ Will Durant (1967). The Story of Civilization Volume 10:Rousseau and Revolution. Simon&Schuster. p. 893.

- ^ a b P.N. Furbank (1992). Diderot:A Critical Biography. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 393.

- ^ a b c P.N. Furbank (1992). Diderot:A Critical Biography. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 394.

- ^ P.N. Furbank (1992). Diderot:A Critical Biography. Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 394–5.

- ^ P.N. Furbank (1992). Diderot:A Critical Biography. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 395.

- ^ Jonathan I. Israel, Enlightenment Contested, Oxford University Press, 2006, pp. 791, 818.

- ^ Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. pp. 651–2.

- ^ P.N. Furbank (1992). Diderot:A Critical Biography. Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 109–115.

- ^ Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. p. 700.

- ^ Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. p. 641.

- ^ a b Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. p. 678.

- ^ Arthur M. Wilson (1972). Diderot. Oxford University Press. p. 175.

- ^ name = "Age of Voltaire 679">Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. p. 679.

- ^ P. N. Furbank. Diderot: A Critical Biography. New York: Knopf, 1992. p. 446

- ^ Will Durant (1965). The Story of Civilization Volume 9:The Age of Voltaire. Simon&Schuster. p. 679.

- ^ David McClellan. Karl Marx: His Life and Thought. New York: Harper & Row, 1973. p. 457

- ^

Ottis Fellows and Norman Torrey (1949). Diderot Studies. 1: vii.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ http://www.nytimes.com/books/98/10/11/specials/schine-niece.html

- ^ http://www.eric-emmanuel-schmitt.com/theatre.cfm?nomenclatureId=1796&catalogid=801&&lang=EN

- ^ http://www.theatreonline.com/Artiste/Eric-Emmanuel-Schmitt/9756

- ^ http://diderot2013-langres.fr/

- ^ http://champagne-ardenne.france3.fr/diderot-2013-langres-en-fete

- ^ Diderot "Le Neveu de Rameau", Les Trésors de la littérature Française, p. 109. Collection dirigée par Edmond Jaloux; http://www.denis-diderot.com/publications.html

- ^ "A Philosophical and Political History of the Settlements and Trade of the Europeans in the East and West Indies". World Digital Library. 1798. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

Further reading

| French and Francophone literature |

|---|

| by category |

| History |

| Movements |

| Writers |

| Countries and regions |

| Portals |

- Anderson, Wilda C. Diderot's Dream. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990.

- App, Urs (2010). The Birth of Orientalism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 978-0-8122-4261-4, pp. 133–87 on Diderot's role in the European discovery of Hinduism and Buddhism.

- Azurmendi, Joxe (1984). Entretien d'un philosophe: Diderot (1713-1784), Jakin, 32: 111-121.

- Ballstadt, Kurt P. A. Diderot: Natural Philosopher. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 2008.

- Blom, Philipp (2010). The Wicked Company. New York: Basic Books

- Blum, Carol (1974). Diderot: The Virtue of a Philosopher

- Brewer, Daniel. Using the Encyclopédie: Ways of Knowing, Ways of Reading. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 2002.

- Clark, Andrew Herrick. Diderot's Part. Aldershot, Hampshire, England: Ashgate, 2008.

- Caplan, Jay. Framed Narratives: Diderot's Genealogy of the Beholder. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1986.

- Crocker, Lester G. (1974). Diderot's Chaotic Order: Approach to a Synthesis

- De la Carrera, Rosalina. Success in Circuit Lies: Diderot's Communicational Practice. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford UP, 1991.

- Fellows, Otis E. (1989). Diderot

- France, Peter (1983). Diderot

- Fontenay, Elisabeth de, and Jacques Proust. Interpréter Diderot Aujourd'hui. Paris: Le Sycomore, 1984.

- Furbank, P. N. (1992). Diderot: A Critical Biography. New York: A. A. Knopf,. ISBN 0-679-41421-5.

- Gregory Efrosini, Mary (2006). Diderot and the Metamorphosis of Species (Studies in Philosophy). New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-95551-3.

- Havens, George R. (1955) The Age of Ideas. New York: Holt ISBN 0-89197-651-5.

- Hayes, Julia Candler. The Representation of the Self in the Theater of La Chaussée, Diderot, and Sade. Ann Arbor, Mich.: University Microfilms International, 1982.

- Kavanagh, Thomas. "The Vacant Mirror: A Study of Mimesis through Diderot's Jacques le Fataliste," in Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century 104 (1973).

- Kuzincki, Jason (2008). "Diderot, Denis (1713–1784)". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 124–5. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- Mason, John H. (1982). The Irresistible Diderot

- Peretz, Eyal (2013). "Dramatic Experiments: Life according to Diderot" State University of New York Press

- Rex, Walter E. Diderot's Counterpoints: The Dynamics of Contrariety in His Major Works. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 1998.

- Saint-Amand, Pierre. Diderot. Saratoga, Calif.: Anma Libri, 1984.

- Simon, Julia (1995). Mass Enlightenment. Albany: State University of New York Press,. ISBN 0-7914-2638-6.

- Tunstall, Kate E. (2011). Blindness and Enlightenment. An Essay. With a new translation of Diderot's Letter on the Blind. Continuum

- Wilson, Arthur McCandless (1972). Diderot, the standard biography

- Vasco, Gerhard M. (1978). "Diderot and Goethe, A Study in Science and Humanism", Librairei Slatkine, Libraire Champion.

Primary sources

- Diderot, Denis, ed. A Diderot Pictorial Encyclopedia of Trades and Industry, Vol. 1 (1993 reprint) excerpt and text search

- Diderot, Denis. Diderot: Political Writings ed. by John Hope Mason and Robert Wokler (1992) excerpt and text search, with introduction

- Main works of Diderot in English translation

- Hoyt, Nellie and Cassirer, Thomas. Encyclopedia, Selections: Diderot, D'Alembert, and a Society of Men of Letters. New York: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1965. LCCN 65--26535. ISBN 0-672-60479-5.

External links

- Works by Denis Diderot at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Denis Diderot at the Internet Archive

- Works by Denis Diderot at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Diderot Search engine in French for human sciences in tribute to Diderot

- Denis Diderot: Rêve d'Alembert (d'Alembert's Dream) (French and English texts)

- Conversation between D'Alembert and Diderot (alternate translation of the first part of the above)

- Denis Diderot Archive Template:En icon

- Denis Diderot Website (in French)

- Template:Fr icon On line version of the Encyclopédie. The articles are classified in alphabetical order (26 files).

- The ARTFL Encyclopédie, provided by the ARTFL Project of the University of Chicago (articles in French, scans of 18th century print copies provided)

- The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project, product of the Scholarly Publishing Office of the University of Michigan Library (an effort to translate the Encyclopédie into English)

- Short biography

- Denis Diderot Bibliography

- Le Neveu de Rameau – Diderot et Goethe

- 1713 births

- 1784 deaths

- People from Langres

- Contributors to the Encyclopédie (1751–72)

- French encyclopedists

- Enlightenment philosophers

- 18th-century French writers

- 18th-century French novelists

- 18th-century philosophers

- Anti-Catholicism in France

- French art critics

- French atheists

- French essayists

- French literary critics

- Writers from Champagne-Ardenne

- French philosophers

- Atheist philosophers

- Lycée Louis-le-Grand alumni

- French erotica writers

- Members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences

- Proto-evolutionary biologists

- Burials at Église Saint-Roch

- Lycée Saint-Louis alumni

- People of the Age of Enlightenment

- French materialists

- Critics of the Catholic Church

- World Digital Library related

- Male essayists

- French male novelists