Eugenics

Eugenics (/juːˈdʒɛnɪks/; from Greek εὐγενής eugenes "well-born" from εὖ eu, "good, well" and γένος genos, "race, stock, kin")[2][3] is a set of beliefs and practices that aims at improving the genetic quality of the human population.[4][5] It is a social philosophy advocating the improvement of human genetic traits through the promotion of higher rates of sexual reproduction for people with desired traits (positive eugenics), or reduced rates of sexual reproduction and sterilization of people with less-desired or undesired traits (negative eugenics), or both.[6] Alternatively, gene selection rather than "people selection" has recently been made possible through advances in gene editing (e.g. CRISPR).[7] The exact definition of eugenics has been a matter of debate since the term was coined. The definition of it as a "social philosophy"—that is, a philosophy with implications for social order—is not universally accepted, and was taken from Frederick Osborn's 1937 journal article "Development of a Eugenic Philosophy".[6] While it has some scientific backing, it is considered pseudoscience, as it lacks factual basis and is based on non-definable objectives. [citation needed]

While eugenic principles have been practiced as far back in world history as Ancient Greece, the modern history of eugenics began in the early 20th century when a popular eugenics movement emerged in Britain[8] and spread to many countries, including the United States and most European countries. In this period, eugenic ideas were espoused across the political spectrum. Consequently, many countries adopted eugenic policies meant to improve the genetic stock of their countries. Such programs often included both "positive" measures, such as encouraging individuals deemed particularly "fit" to reproduce, and "negative" measures such as marriage prohibitions and forced sterilization of people deemed unfit for reproduction. People deemed unfit to reproduce often included people with mental or physical disabilities, people who scored in the low ranges of different IQ tests, criminals and deviants, and members of disfavored minority groups. The eugenics movement became negatively associated with Nazi Germany and the Holocaust—the murder by the German state of approximately 11 million people—when many of the defendants at the Nuremberg trials attempted to justify their human rights abuses by claiming there was little difference between the Nazi eugenics programs and the US eugenics programs.[9] In the decades following World War II, with the institution of human rights, many countries gradually abandoned eugenics policies, although some Western countries, among them Sweden and the US, continued to carry out forced sterilizations for several decades.

Since the 1980s and 1990s when new assisted reproductive technology procedures became available, such as gestational surrogacy (available since 1985), preimplantation genetic diagnosis (available since 1989) and cytoplasmic transfer (first performed in 1996), fear about a possible future revival of eugenics and a widening of the gap between the rich and the poor has emerged, despite the immense medical benefits these technologies offer.

A major criticism of eugenics policies is that, regardless of whether "negative" or "positive" policies are used, they are vulnerable to abuse because the criteria of selection are determined by whichever group is in political power. Furthermore, negative eugenics in particular is considered by many to be a violation of basic human rights, which include the right to reproduction. Another criticism is that eugenic policies eventually lead to a loss of genetic diversity, resulting in inbreeding depression instead due to a low genetic variation.

History

The idea of eugenics to produce better human beings has existed at least since Plato suggested selective mating to produce a guardian class.[11] The idea of eugenics to decrease the birth of inferior human beings has existed at least since William Goodell (1829-1894) advocated the castration and spaying of the insane.[12][13]

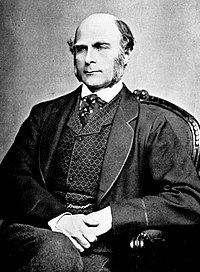

However, the term "eugenics" to describe the modern concept of improving the quality of human beings born into the world was originally developed by Francis Galton. Galton had read his half-cousin Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, which sought to explain the development of plant and animal species, and desired to apply it to humans. Galton believed that desirable traits were hereditary based on biographical studies, Darwin strongly disagreed with his interpretation of the book.[14] In 1883, one year after Darwin's death, Galton gave his research a name: eugenics.[15] Throughout its recent history, eugenics has remained a controversial concept.[16]

Eugenics became an academic discipline at many colleges and universities and received funding from many sources.[17] Organisations formed to win public support, and modify opinion towards responsible eugenic values in parenthood, included the British Eugenics Education Society of 1907, and the American Eugenics Society of 1921. Both sought support from leading clergymen, and modified their message to meet religious ideals.[18] Three International Eugenics Conferences presented a global venue for eugenists with meetings in 1912 in London, and in 1921 and 1932 in New York. Eugenic policies were first implemented in the early 1900s in the United States.[19] It has roots in France, Germany, Great Britain, and the United States.[20] Later, in the 1920s and 30s, the eugenic policy of sterilizing certain mental patients was implemented in other countries, including Belgium,[21] Brazil,[22] Canada,[23] Japan, and Sweden.[24]

The scientific reputation of eugenics started to decline in the 1930s, a time when Ernst Rüdin used eugenics as a justification for the racial policies of Nazi Germany. Nevertheless, in Sweden the eugenics program continued until 1975.[24] In addition to being practised in a number of countries, eugenics was internationally organized through the International Federation of Eugenics Organizations.[25] Its scientific aspects were carried on through research bodies such as the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics,[26] the Cold Spring Harbour Carnegie Institution for Experimental Evolution,[27] and the Eugenics Record Office.[28] Its political aspects involved advocating laws allowing the pursuit of eugenic objectives, such as sterilization laws.[29] Its moral aspects included rejection of the doctrine that all human beings are born equal, and redefining morality purely in terms of genetic fitness.[30] Its racist elements included pursuit of a pure "Nordic race" or "Aryan" genetic pool and the eventual elimination of "less fit" races.[31][32]

As a social movement, eugenics reached its greatest popularity in the early decades of the 20th century. At this point in time, eugenics was practiced around the world and was promoted by governments and influential individuals and institutions. Many countries enacted[33] various eugenics policies and programmes, including: genetic screening, birth control, promoting differential birth rates, marriage restrictions, segregation (both racial segregation and segregation of the mentally ill from the rest of the population), compulsory sterilization, forced abortions or forced pregnancies, and genocide. Most of these policies were later regarded as coercive or restrictive, and now few jurisdictions implement policies that are explicitly labelled as eugenic or unequivocally eugenic in substance. The methods of implementing eugenics varied by country; however, some early 20th century methods involved identifying and classifying individuals and their families, including the poor, mentally ill, blind, deaf, developmentally disabled, promiscuous women, homosexuals, and racial groups (such as the Roma and Jews in Nazi Germany) as "degenerate" or "unfit", the segregation or institutionalization of such individuals and groups, their sterilization, euthanasia, and their mass murder.[34] The practice of euthanasia was carried out on hospital patients in the Aktion T4 centers such as Hartheim Castle.

By the end of World War II, many of the discriminatory eugenics laws were largely abandoned, having become associated with Nazi Germany.[34][35] After World War II, the practice of "imposing measures intended to prevent births within [a population] group" fell within the definition of the new international crime of genocide, set out in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.[36] The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union also proclaims "the prohibition of eugenic practices, in particular those aiming at selection of persons".[37] In spite of the decline in discriminatory eugenics laws, government practices of compulsive sterilization continued into the 21st century. During the ten years President Alberto Fujimori led Peru from 1990 to 2000, allegedly 2,000 persons were involuntarily sterilized.[38] China maintained its coercive one-child policy until 2015 as well as a suite of other eugenics based legislation in order to reduce population size and manage fertility rates of different populations.[39][40][41] In 2007 the United Nations reported coercive sterilisations and hysterectomies in Uzbekistan.[42] During the years 2005–06 to 2012–13, nearly one-third of the 144 California prison inmates who were sterilized did not give lawful consent to the operation.[43]

Developments in genetic, genomic, and reproductive technologies at the end of the 20th century are raising numerous questions regarding the ethical status of eugenics, effectively creating a resurgence of interest in the subject. Some, such as UC Berkeley sociologist Troy Duster, claim that modern genetics is a back door to eugenics.[44] This view is shared by White House Assistant Director for Forensic Sciences, Tania Simoncelli, who stated in a 2003 publication by the Population and Development Program at Hampshire College that advances in pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) are moving society to a "new era of eugenics", and that, unlike the Nazi eugenics, modern eugenics is consumer driven and market based, "where children are increasingly regarded as made-to-order consumer products".[45] In a 2006 newspaper article, Richard Dawkins said that discussion regarding eugenics was inhibited by the shadow of Nazi misuse, to the extent that some scientists would not admit that breeding humans for certain abilities is at all possible. He believes that it is not physically different from breeding domestic animals for traits such as speed or herding skill. Dawkins felt that enough time had elapsed to at least ask just what the ethical differences were between breeding for ability versus training athletes or forcing children to take music lessons, though he could think of persuasive reasons to draw the distinction.[46]

Some, such as Nathaniel C. Comfort from Johns Hopkins University, claim that the change from state-led reproductive-genetic decision-making to individual choice has moderated the worst abuses of eugenics by transferring the decision-making from the state to the patient and their family.[47] Comfort suggests that "[t]he eugenic impulse drives us to eliminate disease, live longer and healthier, with greater intelligence, and a better adjustment to the conditions of society; and the health benefits, the intellectual thrill and the profits of genetic bio-medicine are too great for us to do otherwise."[48] Others, such as bioethicist Stephen Wilkinson of Keele University and Honorary Research Fellow Eve Garrard at the University of Manchester, claim that some aspects of modern genetics can be classified as eugenics, but that this classification does not inherently make modern genetics immoral. In a co-authored publication by Keele University, they stated that "[e]ugenics doesn't seem always to be immoral, and so the fact that PGD, and other forms of selective reproduction, might sometimes technically be eugenic, isn't sufficient to show that they're wrong."[49]

In October 2015, the United Nations' International Bioethics Committee wrote that the ethical problems of human genetic engineering should not be confused with the ethical problems of the 20th century eugenics movements; however, it is still problematic because it challenges the idea of human equality and opens up new forms of discrimination and stigmatization for those who do not want or cannot afford the enhancements.[50]

Meanings and types

The term eugenics and its modern field of study were first formulated by Francis Galton in 1883,[51] drawing on the recent work of his half-cousin Charles Darwin.[52][53] Galton published his observations and conclusions in his book Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development.

The origins of the concept began with certain interpretations of Mendelian inheritance, and the theories of August Weismann.[54] The word eugenics is derived from the Greek word eu ("good" or "well") and the suffix -genēs ("born"), and was coined by Galton in 1883 to replace the word "stirpiculture", which he had used previously but which had come to be mocked due to its perceived sexual overtones.[55] Galton defined eugenics as "the study of all agencies under human control which can improve or impair the racial quality of future generations".[56] Galton did not understand the mechanism of inheritance.[57]

Eugenics has, from the very beginning, meant many different things.[citation needed] Historically, the term has referred to everything from prenatal care for mothers to forced sterilization and euthanasia.[citation needed] To population geneticists, the term has included the avoidance of inbreeding without altering allele frequencies; for example, J. B. S. Haldane wrote that "the motor bus, by breaking up inbred village communities, was a powerful eugenic agent."[58] Debate as to what exactly counts as eugenics has continued to the present day.[59]

Edwin Black, journalist and author of War Against the Weak, claims eugenics is often deemed a pseudoscience because what is defined as a genetic improvement of a desired trait is often deemed a cultural choice rather than a matter that can be determined through objective scientific inquiry.[60] The most disputed aspect of eugenics has been the definition of "improvement" of the human gene pool, such as what is a beneficial characteristic and what is a defect. This aspect of eugenics has historically been tainted with scientific racism.

Early eugenists were mostly concerned with perceived intelligence factors that often correlated strongly with social class. Some of these early eugenists include Karl Pearson and Walter Weldon, who worked on this at the University College London.[14]

Eugenics also had a place in medicine. In his lecture "Darwinism, Medical Progress and Eugenics", Karl Pearson said that everything concerning eugenics fell into the field of medicine. He basically placed the two words as equivalents. He was supported in part by the fact that Francis Galton, the father of eugenics, also had medical training.[61]

Eugenic policies have been conceptually divided into two categories. Positive eugenics is aimed at encouraging reproduction among the genetically advantaged; for example, the reproduction of the intelligent, the healthy, and the successful.[62] Possible approaches include financial and political stimuli, targeted demographic analyses, in vitro fertilization, egg transplants, and cloning.[63] The movie Gattaca provides a fictional example of positive eugenics done voluntarily. Negative eugenics aimed to eliminate, through sterilization or segregation, those deemed physically, mentally, or morally "undesirable".[62] This includes abortions, sterilization, and other methods of family planning.[63] Both positive and negative eugenics can be coercive; abortion for fit women, for example, was illegal in Nazi Germany.[64]

Jon Entine claims that eugenics simply means "good genes" and using it as synonym for genocide is an "all-too-common distortion of the social history of genetics policy in the United States." According to Entine, eugenics developed out of the Progressive Era and not "Hitler's twisted Final Solution".[65]

Implementation methods

According to Richard Lynn, eugenics may be divided into two main categories based on the ways in which the methods of eugenics can be applied.[66]

- Classical Eugenics

- Negative eugenics by provision of information and services, i.e. reduction of unplanned pregnancies and births.[67]

- "Just say no" campaigns.[68]

- Sex education in schools.[69]

- School-based clinics.[70]

- Promoting the use of contraception.[71]

- Emergency contraception.[72]

- Research for better contraceptives.[73]

- Sterilization.[74]

- Abortion.[75]

- Negative eugenics by incentives, coercion and compulsion.[76]

- Incentives for sterilization.[77]

- The Denver Dollar-a-day program, i.e. paying teenage mothers for not becoming pregnant again.[78]

- Incentives for women on welfare to use contraceptions.[79]

- Payments for sterilization in developing countries.[80]

- Curtailment of benefits to welfare mothers.[81]

- Sterilization of the "mentally retarded".[82]

- Sterilization of female criminals.[83]

- Sterilization of male criminals.[84]

- Licences for parenthood.[85][86][87]

- Positive eugenics.[88]

- Financial incentives to have children.[89]

- Selective incentives for childbearing.[90]

- Taxation of the childless.[91]

- Ethical obligations of the elite.[92][clarification needed]

- Eugenic immigration.[93]

- Negative eugenics by provision of information and services, i.e. reduction of unplanned pregnancies and births.[67]

- New Eugenics

Arguments

Doubts on traits triggered by inheritance

The first major challenge to conventional eugenics based upon genetic inheritance was made in 1915 by Thomas Hunt Morgan, who demonstrated the event of genetic mutation occurring outside of inheritance involving the discovery of the hatching of a fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) with white eyes from a family of red-eyes.[101] Morgan claimed that this demonstrated that major genetic changes occurred outside of inheritance and that the concept of eugenics based upon genetic inheritance was not completely scientifically accurate.[101] Additionally, Morgan criticized the view that subjective traits, such as intelligence and criminality, were caused by heredity because he believed that the definitions of these traits varied and that accurate work in genetics could only be done when the traits being studied were accurately defined.[102] In spite of Morgan's public rejection of eugenics, much of his genetic research was absorbed by eugenics.[103][104]

Ethics

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2015) |

A common criticism of eugenics is that "it inevitably leads to measures that are unethical".[105] Historically, this statement is evidenced by the obvious control of one group imposing its agenda on minority groups. This includes programs in England, Germany, and America targeting various groups, including Jews, homosexuals, Muslims, Romani, the homeless, and those with intellectual disabilities.[106]

Many of the ethical concerns from eugenics arise from the controversial past, prompting a discussion on what place, if any, it should have in the future. Advances in science have changed eugenics. In the past, eugenics has had more to do with sterilization and enforced reproduction laws (i.e. no inter-racial marriage and marriage restrictions based on land ownership).[107] Now, in the age of a progressively mapped genome, embryos can be tested for susceptibility to disease, gender, and genetic defects, and alternative methods of reproduction such as in vitro fertilization are becoming more common.[108] In short, eugenics is no longer ex post facto regulation of the living but instead preemptive action on the unborn.

With this change, however, there are ethical concerns which lack adequate attention, and which must be addressed before eugenic policies can be properly implemented in the future. Sterilized individuals, for example, could volunteer for the procedure, albeit under incentive or duress, or at least voice their opinion. The unborn fetus on which these new eugenic procedures are performed cannot speak out, as the fetus lacks the voice to consent or to express his or her opinion.[109] The ability to manipulate a fetus and determine who the child will be is something questioned by many of the opponents of, and even proponents for, eugenic policies.

Societal and political consequences of eugenics call for a place in the discussion on the ethics behind the eugenics movement.[110] Public policy often focuses on issues related to race and gender, both of which could be controlled by manipulation of embryonic genes; eugenics and political issues are interconnected and the political aspect of eugenics must be addressed. Laws controlling the subjects, the methods, and the extent of eugenics will need to be considered in order to prevent the repetition of the unethical events of the past.

Most of the ethical concerns about eugenics involve issues of morality and power. Decisions about the morality and the control of this new science (and the subsequent results of the science) will need to be made as eugenics continue to influence the development of the science and medical fields.

Losing genetic diversity by classifying traits as diseases

Eugenic policies could also lead to loss of genetic diversity, in which case a culturally accepted "improvement" of the gene pool could very likely—as evidenced in numerous instances in isolated island populations (e.g., the dodo, Raphus cucullatus, of Mauritius)—result in extinction due to increased vulnerability to disease, reduced ability to adapt to environmental change, and other factors both known and unknown. A long-term species-wide eugenics plan might lead to a scenario similar to this because the elimination of traits deemed undesirable would reduce genetic diversity by definition.[111]

Edward M. Miller claims that, in any one generation, any realistic program should make only minor changes in a fraction of the gene pool, giving plenty of time to reverse direction if unintended consequences emerge, reducing the likelihood of the elimination of desirable genes.[112] Miller also argues that any appreciable reduction in diversity is so far in the future that little concern is needed for now.[112]

While the science of genetics has increasingly provided means by which certain characteristics and conditions can be identified and understood, given the complexity of human genetics, culture, and psychology there is at this point no agreed objective means of determining which traits might be ultimately desirable or undesirable. Some diseases such as sickle-cell disease and cystic fibrosis respectively confer immunity to malaria and resistance to cholera when a single copy of the recessive allele is contained within the genotype of the individual. Reducing the instance of sickle-cell disease genes in Africa where malaria is a common and deadly disease could indeed have extremely negative net consequences.

However, some genetic diseases such as haemochromatosis can increase susceptibility to illness, cause physical deformities, and other dysfunctions, which provides some incentive for people to re-consider some elements of eugenics.

Autistic people have advocated a shift in perception of autism spectrum disorders as complex syndromes rather than diseases that must be cured. Proponents of this view reject the notion that there is an "ideal" brain configuration and that any deviation from the norm is pathological; they promote tolerance for what they call neurodiversity.[113] Baron-Cohen argues that the genes for Asperger's combination of abilities have operated throughout recent human evolution and have made remarkable contributions to human history.[114] The possible reduction of autism rates through selection against the genetic predisposition to autism is a significant political issue in the autism rights movement, which claims that autism is a part of neurodiversity.

Many culturally Deaf people oppose attempts to cure deafness, believing instead deafness should be considered a defining cultural characteristic not a disease.[115][116][117] Some people have started advocating the idea that deafness brings about certain advantages, often termed "Deaf Gain."[118][119]

Heterozygous recessive traits

The heterozygote test is used for the early detection of recessive hereditary diseases, allowing for couples to determine if they are at risk of passing genetic defects to a future child.[120] The goal of the test is to estimate the likelihood of passing the hereditary disease to future descendants.[120]

Recessive traits can be severely reduced, but never eliminated unless the complete genetic makeup of all members of the pool was known, as aforementioned. As only very few undesirable traits, such as Huntington's disease, are dominant, it could be argued[by whom?] from certain perspectives that the practicality of "eliminating" traits is quite low.[citation needed]

There are examples of eugenic acts that managed to lower the prevalence of recessive diseases, although not influencing the prevalence of heterozygote carriers of those diseases. The elevated prevalence of certain genetically transmitted diseases among the Ashkenazi Jewish population (Tay–Sachs, cystic fibrosis, Canavan's disease, and Gaucher's disease), has been decreased in current populations by the application of genetic screening.[121]

Pleiotropic genes

Pleiotropy occurs when one gene influences multiple, seemingly unrelated phenotypic traits, an example being phenylketonuria, which is a human disease that affects multiple systems but is caused by one gene defect.[122] Andrzej Pękalski, from the University of Wrocław, argues that eugenics can cause harmful loss of genetic diversity if a eugenics program selects for a pleiotropic gene that is also associated with a positive trait. Pekalski uses the example of a coercive government eugenics program that prohibits people with myopia from breeding but has the unintended consequence of also selecting against high intelligence since the two go together.[123]

Supporters and critics

At its peak of popularity, eugenics was supported by a wide variety of prominent people, including Winston Churchill,[124] Margaret Sanger,[125][126] Marie Stopes,[127][128] H. G. Wells,[129] Norman Haire, Havelock Ellis, Theodore Roosevelt, Herbert Hoover, George Bernard Shaw, John Maynard Keynes, John Harvey Kellogg, Robert Andrews Millikan,[130] Linus Pauling,[131] Sidney Webb,[132][133][134] and W. E. B. Du Bois.[135]

In 1909 the Anglican clergymen William Inge and James Peile both wrote for the British Eugenics Education Society. Inge was an invited speaker at the 1921 International Eugenics Conference, which was also endorsed by the Roman Catholic Archbishop of New York Patrick Joseph Hayes.[18] In 1925 Adolf Hitler praised and incorporated eugenic ideas in Mein Kampf and emulated eugenic legislation for the sterilization of "defectives" that had been pioneered in the United States.[136]

Early critics of the philosophy of eugenics included the American sociologist Lester Frank Ward,[137] the English writer G. K. Chesterton, the German-American anthropologist Franz Boas,[138] and Scottish tuberculosis pioneer and author Halliday Sutherland. Ward's 1913 article "Eugenics, Euthenics, and Eudemics", Chesterton's 1917 book Eugenics and Other Evils, and Boas' 1916 article "Eugenics" (published in The Scientific Monthly) were all harshly critical of the rapidly growing movement. Sutherland identified eugenists as a major obstacle to the eradication and cure of tuberculosis in his 1917 address "Consumption: Its Cause and Cure",[139] and criticism of eugenists and Neo-Malthusians in his 1921 book Birth Control led to a writ for libel from the eugenist Marie Stopes. Several biologists were also antagonistic to the eugenics movement, including Lancelot Hogben.[140] Other biologists such as J. B. S. Haldane and R. A. Fisher expressed skepticism that sterilization of "defectives" would lead to the disappearance of undesirable genetic traits.[141]

Some supporters of eugenics later reversed their positions on it. For example, H. G. Wells, who had called for "the sterilization of failures" in 1904,[129] stated in his 1940 book The Rights of Man: Or What are we fighting for? that among the human rights he believed should be available to all people was "a prohibition on mutilation, sterilization, torture, and any bodily punishment".[142]

Among institutions, the Catholic Church was an opponent of state-enforced sterilizations.[143] Attempts by the Eugenics Education Society to persuade the British government to legalise voluntary sterilisation were opposed by Catholics and by the Labour Party.[page needed] The American Eugenics Society initially gained some Catholic supporters, but Catholic support declined following the 1930 papal encyclical Casti connubii.[18] In this, Pope Pius XI explicitly condemned sterilization laws: "Public magistrates have no direct power over the bodies of their subjects; therefore, where no crime has taken place and there is no cause present for grave punishment, they can never directly harm, or tamper with the integrity of the body, either for the reasons of eugenics or for any other reason."[144]

See also

Notes

- ^ Currell, Susan; Christina Cogdell (2006). Popular Eugenics: National Efficiency and American Mass Culture in The 1930s. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press. p. 203. ISBN 0-8214-1691-X.

- ^ "eugenics". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ "γένος". A Greek–English Lexicon.

- ^ "Eugenics". Unified Medical Language System (Psychological Index Terms). National Library of Medicine. 26 September 2010.

- ^ Galton, Francis (July 1904). "Eugenics: Its Definition, Scope, and Aims". The American Journal of Sociology. X (1): 82, 1st paragraph. Bibcode:1904Natur..70...82. doi:10.1038/070082a0. Archived from the original on 2007-11-17. Retrieved 2010-12-27.

Eugenics is the science which deals with all influences that improve the inborn qualities of a race; also with those that develop them to the utmost advantage.

{{cite journal}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 2007-11-03 suggested (help); Check|bibcode=length (help) - ^ a b Osborn, Frederick (June 1937). "Development of a Eugenic Philosophy". American Sociological Review. 2 (3): 389–397. doi:10.2307/2084871.

- ^ "CRISPR and Targeted Genome Editing: A New Era in Molecular Biology". New England Biolab. 2014. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ^ "Eugenic Ideas, Political Interests and Policy Variance Immigration and Sterilization Policy in Britain and U.S." 1 Jan 2001. Retrieved 2015-03-20.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Alison Bashford, Philippa Levine. The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics. Oxford University Press. p. 327.

- ^ Francis Galton (1874) "On men of science, their nature and their nurture," Proceedings of the Royal Institution of Great Britain, 7 : 227-236.

- ^ "Eugenics". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Center for the Study of Language and Information (CSLI), Stanford University. Jul 2, 2014. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ^ The American Journal of Insanity. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ Keeping America Sane. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ a b "Eugenics: Immigration and Asylum from 1990 to Present". Retrieved 2013-09-23.

- ^ Watson, James D.; Berry, Andrew (2009). DNA: The Secret of Life. Knopf.

- ^ Blom 2008, p. 336.

- ^ Allen, Garland E. (2004). "Was Nazi eugenics created in the US?". EMBO Reports. 5 (5): 451–2. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400158. PMC 1299061.

- ^ a b c Baker, G. J. (2014). "Christianity and Eugenics: The Place of Religion in the British Eugenics Education Society and the American Eugenics Society, c.1907-1940". Social History of Medicine. 27 (2). Oxford University Press: 281–302. doi:10.1093/shm/hku008. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ Barrett, Deborah; Kurzman, Charles (October 2004). "Globalizing Social Movement Theory: The Case of Eugenics" (PDF). Theory and Society. 33 (5): 487–527. doi:10.2307/4144884. JSTOR 4144884.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hawkins, Mike (1997). Social Darwinism in European and American Thought. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 62, 292. ISBN 0-521-57434-X.

- ^ "The National Office of Eugenics in Belgium". Science. 57 (1463): 46. 12 January 1923. Bibcode:1923Sci....57R..46.. doi:10.1126/science.57.1463.46.

- ^ dos Santos, Sales Augusto; Hallewell, Laurence (January 2002). "Historical Roots of the 'Whitening' of Brazil". Latin American Perspectives. 29 (1): 61–82. doi:10.1177/0094582X0202900104. JSTOR 3185072.

- ^ McLaren, Angus (1990). Our Own Master Race: Eugenics in Canada, 1885–1945. Toronto: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-7710-5544-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)[page needed] - ^ a b James, Steve. "Social Democrats implemented measures to forcibly sterilise 62,000 people". World Socialist Web Site. International Committee of the Fourth International.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Black 2003, p. 240.

- ^ Black 2003, p. 286.

- ^ Black 2003, p. 40.

- ^ Black 2003, p. 45.

- ^ Black 2003, Chapter 6: The United States of Sterilization.

- ^ Black 2003, p. 237.

- ^ Black 2003, Chapter 5: Legitimizing Raceology.

- ^ Black 2003, Chapter 9: Mongrelization.

- ^ Ridley, Matt (1999). Genome: The Autobiography of a Species in 23 Chapters. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 290–1. ISBN 978-0-06-089408-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b Black 2003.

- ^ Lynn 2001. p. 18 "By the middle decades of the twentieth century, eugenics had become widely accepted throughout the whole of the economically developed world, with the exception of the Soviet Union."

- ^ Article 2 of the Convention defines genocide as any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such as:

- Killing members of the group;

- Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

- Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

- ^ "Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union: Article 3, Section 2".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ CNN, Peru will not prosecute former President over sterilization campaign, Retrieved August 30, 2014. http://www.cnn.com/2014/01/25/world/americas/peru-sterilization/

- ^ Dikötter, F. (1998). Imperfect conceptions: medical knowledge, birth defects, and eugenics in China. Columbia University Press.

- ^ Edge. Chinese Eugenics. Retrieved on August 30, 2014. http://edge.org/response-detail/23838/

- ^ Dikotter, F. (1999). Director, Contemporary China Institute, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London,"'The legislation imposes decisions'; laws about eugenics in China,". UNESCO Courier, 1.

- ^ BBC News, Uzbekistan's policy of secretly sterilizing women, retrieved on August 30, 2014. http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-17612550

- ^ Johnson, Corey G (June 20, 2014). "Calif. female inmates sterilized illegally". USA Today. Retrieved August 30, 2014.

- ^ Epstein, Charles J (1 November 2003). "Is modern genetics the new eugenics?". Genetics in Medicine. 5 (6): 469–475. doi:10.1097/01.GIM.0000093978.77435.17.

- ^ Tania Simoncelli, "Pre-Implantation Genetic Diagnosis and Selection: from disease prevention to customised conception", Different Takes, No. 24 (Spring 2003). http://genetics.live.radicaldesigns.org/downloads/200303_difftakes_simoncelli.pdf Retrieved on September 18, 2013.

- ^ From the Afterward, by Richard Dawkins, The Herald, (2006). http://www.heraldscotland.com/from-the-afterword-1.836155 Retrieved on Oct 17, 2013

- ^ Comfort, Nathaniel (12 November 2012). "The Eugenics Impulse". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ^ Comfort, Nathaniel. The Science of Human Perfection: How Genes Became the Heart of American Medicine. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-16991-1.

- ^ Eugenics and the Ethics of Selective Reproduction, Stephen and Eve Garrard, published by Keele University 2013. http://www.keele.ac.uk/media/keeleuniversity/ri/risocsci/eugenics2013/Eugenics%20and%20the%20ethics%20of%20selective%20reproduction%20Low%20Res.pdf Retrieved on September 18, 2013

- ^ "Report of the IBC on Updating Its Reflection on the Human Genome and Human Rights" (PDF). International Bioethics Committee. October 2, 2015. p. 27. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

The goal of enhancing individuals and the human species by engineering the genes related to some characteristics and traits is not to be confused with the barbarous projects of eugenics that planned the simple elimination of human beings considered as 'imperfect' on an ideological basis. However, it impinges upon the principle of respect for human dignity in several ways. It weakens the idea that the differences among human beings, regardless of the measure of their endowment, are exactly what the recognition of their equality presupposes and therefore protects. It introduces the risk of new forms of discrimination and stigmatization for those who cannot afford such enhancement or simply do not want to resort to it. The arguments that have been produced in favour of the so-called liberal eugenics do not trump the indication to apply the limit of medical reasons also in this case.

- ^ Galton, Francis (1883). Inquiries into Human Faculty and its Development. London: Macmillan Publishers. p. 199.

- ^ "Correspondence between Francis Galton and Charles Darwin". Galton.org. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- ^ "The correspondence of Charles Darwin, volume 17: 1869". Darwin Correspondence Project. University of Cambridge. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- ^ Blom 2008, pp. 335–336.

- ^ Lester Frank Ward; Emily Palmer Cape; Sarah Emma Simons (1918). "Eugenics, Euthenics and Eudemics". Glimpses of the cosmos. G. P. Putnam's sons. pp. 382–. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ Cited in Black 2003, p. 18

- ^ "Galton and the beginnings of Eugenics, James Watson :: DNA Learning Center". Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ Haldane, J. (1940). "Lysenko and Genetics". Science and Society. 4 (4).

- ^ A discussion of the shifting meanings of the term can be found in Paul, Diane (1995). Controlling human heredity: 1865 to the present. New Jersey: Humanities Press. ISBN 1-57392-343-5.

- ^ Black, Edwin (2004). War Against the Weak. Thunder's Mouth Press. p. 370. ISBN 978-1-56858-321-1.

- ^ Salgirli SG (July 2011). "Eugenics for the doctors: medicine and social control in 1930s Turkey". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 66 (3): 281–312. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrq040. PMID 20562206.

- ^ a b http://journals1.scholarsportal.info.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/tmp/15510468026065759357.pdf%7Cdate=September 2013[dead link]

- ^ a b Glad, John (2008). Future Human Evolution: Eugenics in the Twenty-First Century (PDF). Hermitage Publishers. ISBN 1-55779-154-6.

- ^ Pine, Lisa (1997). Nazi Family Policy, 1933–1945. Berg. pp. 19–. ISBN 978-1-85973-907-5. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ "Let's (Cautiously) Celebrate the "New Eugenics"". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ Lynn 2001. Part III. The Implementation of Classical Eugenics pp. 137–244 Part IV. The New Eugenics pp. 245–320

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 165–186

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 169–170

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 170–172

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 172–174

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 174–176

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 176–178

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 179–181

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 181–182

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 182–185

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 187–204

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 188–189

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 189–190

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 190–191

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 191–192

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 194–195

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 196–199

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 199–201

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 201–203

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 205–214

- ^ Wired. It's time to consider restricting human breeding. Zoltan Istvan (August 2014)http://www.wired.co.uk/news/archive/2014-08/14/time-to-restrict-human-breeding

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 211–213. Richard Lynn argued that to have an effective licensing program, reversible sterilization methods should be used. Those who wish to have children would obtain the licence and have the sterilization reversed. Lynn stated that the proposals made by Francis Galton, Hugh LaFollette and John Westman would not be effective from the eugenics' viewpoint, since those without licences could still have children. The proposal by David Lykken would be only slightly effective.

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 215–224

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 215–217

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 217–219

- ^ Lynn 2001. p. 219

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 220–221

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 222–224

- ^ Lynn 2001. p. 246

- ^ Lynn 2001. p. 247

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 248–251

- ^ Lynn 2001. p. 252

- ^ Lynn 2001. p. 253

- ^ Lynn 2001. p. 254

- ^ Lynn 2001. pp. 254–255

- ^ a b Blom 2008, pp. 336–7.

- ^ Flaws in Eugenics Research, by Garland E. Allen, Washington University. http://www.eugenicsarchive.org/html/eugenics/essay5text.html retrieved on Oct. 03, 2013.

- ^ Scientific Origins of Eugenics, Elof Carlson, State University of New York at Stony Brook. http://www.eugenicsarchive.org/html/eugenics/essay2text.html Retrieved on Oct. 03, 2013.

- ^ Retrospectives, Eugenics and Economics in the Progressive Era, Journal of Economic Perspectives (2005). http://www.princeton.edu/~tleonard/papers/retrospectives.pdf Retrieved on Oct. 03, 2013

- ^ Lynn 2001. The Ethical Principles of Classical Eugenics – Conclusions P. 241 "A number of the opponents of eugenics have resorted to the slippery slope argument, which states that although a number of eugenic measures are unobjectionable in themselves, they could lead to further measures that would be unethical."

- ^ Kessler, K. (2007). Physicians and the Nazi euthanasia program. International Journal of Mental Health, 36(1), 4-16. doi: 10.2753/IMH0020-7411360101

- ^ Fischer, B. A. (2012). Maltreatment of people with serious mental illness in the early 20th century: A focus on Nazi Germany and eugenics in America. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 200, 1096-1100. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318275d391

- ^ Hoge, S. K., & Appelbaum, P. S. (2012). Ethics and neuropsychiatric genetics: A review of major issues. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 15, 1547-1557. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711001982

- ^ Baird, S. L. (2007). Designer babies: Eugenics repackaged or consumer options? Technology Teacher, 66 (7), 12-16.

- ^ Bentwich, M (2013). "On the inseparability of gender eugenics, ethics, and public policy: An Israeli perspective". American Journal of Bioethics. 13 (10): 43–45. doi:10.1080/15265161.2013.828128.

- ^ (Galton 2001, 48)[full citation needed]

- ^ a b Miller, Edward M. (1997). "Eugenics: Economics for the Long Run". Research in Biopolitics. 5: 391–416.

- ^ Williams CC (2005). "In search of an Asperger". In Stoddart KP (ed.). Children, Youth and Adults with Asperger Syndrome: Integrating Multiple Perspectives. Jessica Kingsley. pp. 242–52. ISBN 1-84310-319-2.

The life prospects of people with AS would change if we shifted from viewing AS as a set of dysfunctions, to viewing it as a set of differences that have merit.

- ^ Baron-Cohen S (2008). "The evolution of brain mechanisms for social behavior". In Crawford C, Krebs D (eds.) (ed.). Foundations of Evolutionary Psychology. Lawrence Erlbaum. pp. 415–32. ISBN 0-8058-5957-8.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ "Sound and Fury - Cochlear Implants - Essay". www.pbs.org. PBS. Retrieved 2015-08-01.

- ^ "Understanding Deafness: Not Everyone Wants to Be 'Fixed'". www.theatlantic.com. The Atlantic. Retrieved 2015-08-01.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Why not all deaf people want to be cured". www.telegraph.co.uk. The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2015-08-02.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Deaf Gain". University of Minnesota Press. Retrieved 2015-09-15.

- ^ Bauman, H-Dirksen L.; Murray, Joseph M. (Fall 2009). "Reframing: From Hearing Loss to Deaf Gain" (PDF). Deaf Studies Digital Journal.

- ^ a b http://www.drze.de/in-focus/predictive-genetic-testing/modules/heterozygote-test-screening-programmes |Heterozygote test / Screening programmes, German Reference Centre for Ethics in the Life Sciences, (Last retrieved Nov. 28, 2014).

- ^ "Fatal Gift: Jewish Intelligence and Western Civilization". Archived from the original on 13 August 2009.

- ^ Stearns, F. W. (2010). "One Hundred Years of Pleiotropy: A Retrospective". Genetics. 186 (3): 767–773. doi:10.1534/genetics.110.122549.

- ^ Jones, A (2000). "Effect of eugenics on the evolution of populations". European Physical Journal B. 17 (2): 329–332. Bibcode:2000EPJB...17..329P. doi:10.1007/s100510070148.

- ^ "Winston Churchill and Eugenics". The Churchill Centre and Museum. 2009-05-31. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- ^ Margaret Sanger, quoted in Katz, Esther; Engelman, Peter (2002). The Selected Papers of Margaret Sanger. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press. p. 319. ISBN 978-0-252-02737-6.

Our ... campaign for Birth Control is not merely of eugenic value, but is practically identical in ideal with the final aims of Eugenics

- ^ Franks, Angela (2005). Margaret Sanger's eugenic legacy. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-7864-2011-7.

... her commitment to eugenics was constant ... until her death

- ^ Soloway, R. A. (1996). “Marie Stopes and The English Birth Control Movement”. “Marie Stopes and The English Birth Control Movement”. London: The Galton Institute. Robert A. Peel, editor.

- ^ Rose, J. (1993). Marie Stopes and the Sexual Revolution. London: Faber and Faber Limited.

- ^ a b Jacky Turner, Animal Breeding, Welfare and Society Routledge, 2010. ISBN 1844075893, (p.296).

- ^ "Judgment At Pasadena", Washington Post, March 16, 2000, p. C1. Retrieved on March 30, 2007.

- ^ Mendelsohn, Everett (March–April 2000). "The Eugenic Temptation". Harvard Magazine.

- ^ Gordon, Linda (2002). The Moral Property of Women: A History of Birth Control Politics in America. University of Illinois Press. p. 196. ISBN 0-252-02764-7.

- ^ Keynes, John Maynard (1946). "Opening remarks: The Galton Lecture". The Eugenics Review. 38 (1): 39–40.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Okuefuna, David. "Racism: a history". BBC.co.uk. BBC. Archived from the original on 14 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-12.

- ^ "Awakenings: On Margaret Sanger". Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ Black 2003, pp. 274–295.

- ^ Ferrante, Joan (1 January 2010). Sociology: A Global Perspective. Cengage Learning. pp. 259–. ISBN 978-0-8400-3204-1.

- ^ Turda, Marius (2010). "Race, Science and Eugenics in the Twentieth Century". In Bashford, Alison; Levine, Philippa (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics. Oxford University Press. pp. 72–73. ISBN 0-19-988829-9.

- ^ "Consumption: Its Cause and Cure" An Address by Dr Halliday Sutherland on 4 September 1917, published by the Red Triangle Press.

- ^ "Lancelot Hogben, who developed his critique of eugenics and distaste for racism in the period...he spent as Professor of Zoology at the University of Cape Town". Alison Bashford and Philippa Levine, The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics. Oxford; Oxford University Press, 2010 ISBN 0199706530 (p.200)

- ^ "Whatever their disagreement on the numbers, Haldane, Fisher, and most geneticists could support Jennings's warning: To encourage the expectation that the sterilization of defectives will "solve the problem of hereditary defects, close up the asylums for feebleminded and insane, do away with prisons, is only to subject society to deception". Daniel J. Kevles, In the Name of Eugenics. University of California Press, 1985. ISBN 0520057635 (p. 166).

- ^ Andrew Clapham, Human Rights:A Very Short Introduction. Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 9780199205523 (pp. 29-31).

- ^ Congar, Yves M.-J. (1953). The Catholic Church and the race question (pdf). Paris, France: UNESCO. Retrieved 2015-07-03.

4. The State is not entitled to deprive an individual of his procreative power simply for material (eugenic) purposes. But it is entitled to isolate individuals who are sick and whose progeny would inevitably be seriously tainted.

- ^ Pope Pius XI. "Casti connubii".

References

- Black, Edwin (2003). War Against the Weak: Eugenics and America's Campaign to Create a Master Race. Four Walls Eight Windows. ISBN 1-56858-258-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Larson, Edward J. (2004). "Evolution". Modern Library. ISBN 0-679-64288-9.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lynn, Richard (June 30, 2001). Eugenics: a reassessment (Hardcover). 88 Post Road West, Westport, Connecticut 06881: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-95822-1. ISSN 1063-2158. LCCN 00052459

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link)

- Histories of eugenics (academic accounts)

- Carlson, Elof Axel (2001). The Unfit: A History of a Bad Idea. Cold Spring Harbor NY: Cold Spring Harbor Press. ISBN 0-87969-587-0.

- Engs, Ruth C. (2005). The Eugenics Movement: An Encyclopedia. Westport CT: Greenwood Publishing. ISBN 0-313-32791-2.

- Farrall, Lyndsay (1985). The origins and growth of the English eugenics movement, 1865–1925. Garland Pub. ISBN 978-0-8240-5810-4.

- Kevles, Daniel J. (1985). In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05763-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Largent, Mark (2008). Breeding Contempt: The History of Coerced Sterilization in the United States. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-4183-9.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (2004). "Deadly medicine: creating the master race".

- Wyndham, Diana (2003). Eugenics in Australia : striving for national fitness. London: Galton Institute. ISBN 978-0-9504066-7-1.

- Histories of hereditarian thought

- Barkan, Elazar (1992). The retreat of scientific racism: changing concepts of race in Britain and the United States between the world wars. New York: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ewen, Elizabeth; Ewen, Stuart (2006). Typecasting: On the Arts and Sciences of Human Inequality (1st ed.). New York: Seven Stories Press. ISBN 978-1-58322-735-0.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (1981). The mismeasure of man. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-01489-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gillette, Aaron (2007). The Nature-Nurture Debate in the Twentieth Century. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-10845-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Criticisms of eugenics

- Blom, Philipp (2008). The Vertigo Years: Change and Culture in the West, 1900–1914. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. pp. 335–6. ISBN 978-0-7710-1630-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - D'Souza, Dinesh (1995). The End of Racism: Principles for a Multicultural Society. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-02-908102-5.

- Galton, David (2002). Eugenics: The Future of Human Life in the 21st Century. London: Abacus. ISBN 0-349-11377-7.

- Goldberg, Jonah (2007). Liberal Fascism: The Secret History of the American Left, from Mussolini to the Politics of Meaning (1st ed.). New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-51184-1.

- Joseph, Jay (2004). The Gene Illusion: Genetic Research in Psychiatry and Psychology Under the Microscope. New York: Algora. ISBN 978-0-87586-343-6. Archived from the original on 12 May 2009.

- Joseph J (June 2005). "The 1942 'euthanasia' debate in the American Journal of Psychiatry". History of Psychiatry. 16 (62 Pt 2): 171–9. doi:10.1177/0957154x05047004. PMID 16013119.

- Joseph, Jay (2006). The Missing Gene: Psychiatry, Heredity, and the Fruitless Search for Genes. New York: Algora. ISBN 978-0-87586-410-5. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009.

- Kerr, Anne; Shakespeare, Tom (2002). Genetic Politics: from Eugenics to Genome. Cheltenham: New Clarion. ISBN 978-1-873797-25-9.

- Maranto, Gina (1996). Quest for perfection: the drive to breed better human beings. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-684-80029-2.

- Ordover, Nancy (2003). American Eugenics: Race, Queer Anatomy, and the Science of Nationalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-3559-5.

- Shakespeare, Tom (1995). "Back to the Future? New Genetics and Disabled People". Critical Social Policy. 46 (44–45): 22–35. doi:10.1177/026101839501504402.

- Smith, Andrea (2005). Conquest : sexual violence and American Indian genocide. Cambridge, Massachusetts: South End Press. ISBN 978-0-89608-743-9.

- Wahlsten D (1997). "Leilani Muir versus the philosopher king: eugenics on trial in Alberta". Genetica. 99 (2–3): 185–98. doi:10.1007/BF02259522. PMID 9463073.