Flamenco

| Flamenco | |

|---|---|

Flamenco dancer with traditional dress | |

| Cultural origins | Andalusia, Spain |

| Typical instruments | |

| Subgenres | |

| New flamenco | |

| Fusion genres | |

| Flamenco chill | |

| Other topics | |

Flamenco (Spanish pronunciation: [flaˈmeŋko]), in its strictest sense, is a professionalized art-form based on the various folkloric music traditions of southern Spain in the autonomous community of Andalusia. In a wider sense, it refers to these musical traditions and more modern musical styles which have themselves been deeply influenced by and become blurred with the development of flamenco over the past two centuries. It includes cante (singing), toque (guitar playing), baile (dance), jaleo (vocalizations and chorus clapping), palmas (handclapping) and pitos (finger snapping).[1]

The oldest record of flamenco dates to 1774 in the book Las Cartas Marruecas by José Cadalso.[2] Flamenco has been influenced by and associated with the Romani people in Spain; however, its origin and style are uniquely Andalusian.[3][4]

The origin of flamenco is a subject of disagreement. The Diccionario de la lengua española (Dictionary of the Spanish Language) primarily attributes the creation of the style to the Spanish Romani.[5] Of the hypotheses regarding its origin, the most widespread states that flamenco was developed through the cross-cultural interchange between native Andalusians, Romani, Castilians, Moors and Sephardi Jews that occurred in Andalusia.[6][citation needed] The early 20th century poet and dramatist Federico García Lorca wrote that the presence of flamenco in Andalusia significantly predates the arrival of Romani people to the region.[7]

Flamenco has become popular all over the world and is taught in many non-Hispanic countries, especially the United States and Japan. In Japan, there are more flamenco academies than there are in Spain.[8][9] On November 16, 2010, UNESCO declared flamenco one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.[10]

Etymology

There are many suggestions for the origin of the word flamenco as a musical term (summarized below) but no solid evidence for any of them.[11] The word was not recorded as a musical and dance term until the late 18th century.

One theory, proposed by Andalusian historian and nationalist Blas Infante in his 1933 book Orígenes de lo Flamenco y Secreto del Cante Jondo suggested that the word flamenco comes in fact from the Hispano-Arabic term fellah mengu, meaning "expelled peasant". This term referred to the many Andalusians of the Islamic faith, the Moriscos who remained, and in order to avoid religious persecution, joined with the Roma newcomers.[12][13] Another theory is that the Spanish word flamenco could have been a derivative of the Spanish word flama, meaning "fire" or "flame". The word flamenco may have come to be used for fiery behaviour, which could have come to be applied to the Gitano players and performers.[14]

Palos

Palos (formerly known as cantes) are flamenco styles, classified by criteria such as rhythmic pattern, mode, chord progression, stanzaic form and geographic origin. There are over 50 different palos, some are sung unaccompanied while others have guitar or other accompaniment. Some forms are danced while others are not. Some are reserved for men and others for women while some may be performed by either, though these traditional distinctions are breaking down: the Farruca, for example, once a male dance, is now commonly performed by women too.

There are many ways to categorize Palos but they traditionally fall into three classes: the most serious is known as cante jondo (or cante grande), while lighter, frivolous forms are called cante chico. Forms that do not fit either category are classed as cante intermedio.[15]

These are the best known palos:[16][17]

- Alegrías

- Bulerías

- Bulerías por soleá (soleá por bulerías)

- Caracoles

- Cartageneras

- Fandango

- Fandango de Huelva

- Fandango Malagueño

- Farruca

- Granaínas

- Guajiras

- Malagueñas

- Martinete

- Mineras

- Peteneras

- Rondeñas

- Saeta

- Seguiriyas

- Soleá

- Tangos

- Tanguillos

- Tarantos

- Tientos

- Villancicos

Music

Structure

A typical flamenco recital with voice and guitar accompaniment, comprises a series of pieces (not exactly "songs") in different palos. Each song of a set of verses (called copla, tercio, or letras), which are punctuated by guitar interludes called falsetas. The guitarist also provides a short introduction which sets the tonality, compás and tempo of the cante.[18] In some palos, these falsetas are also played with certain structures too; for example, the typical sevillanas is played in an AAB pattern, where A and B are the same falseta with only a slight difference in the ending.[19]

Harmony

Flamenco uses the Flamenco mode (which can also be described as the modern Phrygian mode (modo frigio), or a harmonic version of that scale with a major 3rd degree), in addition to the major and minor scales commonly used in modern Western music. The Phrygian mode occurs in palos such as soleá, most bulerías, siguiriyas, tangos and tientos.

A typical chord sequence, usually called the "Andalusian cadence" may be viewed as in a modified Phrygian: in E the sequence is Am–G–F–E.[20] According to Manolo Sanlúcar E is here the tonic, F has the harmonic function of dominant while Am and G assume the functions of subdominant and mediant respectively.[21]

Guitarists tend to use only two basic inversions or "chord shapes" for the tonic chord (music), the open 1st inversion E and the open 3rd inversion A, though they often transpose these by using a capo. Modern guitarists such as Ramón Montoya, have introduced other positions: Montoya himself started to use other chords for the tonic in the modern Dorian sections of several palos; F♯ for tarantas, B for granaínas and A♭ for the minera. Montoya also created a new palo as a solo for guitar, the rondeña in C♯ with scordatura. Later guitarists have further extended the repertoire of tonalities, chord positions and scordatura.

There are also palos in major mode; most cantiñas and alegrías, guajiras, some bulerías and tonás, and the cabales (a major type of siguiriyas). The minor mode is restricted to the Farruca, the milongas (among cantes de ida y vuelta), and some styles of tangos, bulerías, etc. In general traditional palos in major and minor mode are limited harmonically to two-chord (tonic–dominant) or three-chord (tonic–subdominant–dominant) progressions. (Rossy 1998:92) However modern guitarists have introduced chord substitution, transition chords, and even modulation.

Fandangos and derivative palos such as malagueñas, tarantas and cartageneras are bimodal: guitar introductions are in Phrygian mode while the singing develops in major mode, modulating to Phrygian at the end of the stanza. (Rossy 1998:92)

Melody

Dionisio Preciado, quoted by Sabas de Hoces [22] established the following characteristics for the melodies of flamenco singing:

- Microtonality: presence of intervals smaller than the semitone.

- Portamento: frequently, the change from one note to another is done in a smooth transition, rather than using discrete intervals.

- Short tessitura or range: Most traditional flamenco songs are limited to a range of a sixth (four tones and a half). The impression of vocal effort is the result of using different timbres, and variety is accomplished by the use of microtones.

- Use of enharmonic scale. While in equal temperament scales, enharmonics are notes with identical pitch but different spellings (e.g. A♭ and G♯); in flamenco, as in unequal temperament scales, there is a microtonal intervalic difference between enharmonic notes.

- Insistence on a note and its contiguous chromatic notes (also frequent in the guitar), producing a sense of urgency.

- Baroque ornamentation, with an expressive, rather than merely aesthetic function.

- Apparent lack of regular rhythm, especially in the siguiriyas: the melodic rhythm of the sung line is different from the metric rhythm of the accompaniment.

- Most styles express sad and bitter feelings.

- Melodic improvisation: flamenco singing is not, strictly speaking, improvised, but based on a relatively small number of traditional songs, singers add variations on the spur of the moment.

Musicologist Hipólito Rossy adds the following characteristics (Rossy 1997: 97):

- Flamenco melodies are characterized by a descending tendency, as opposed to, for example, a typical opera aria, they usually go from the higher pitches to the lower ones, and from forte to piano, as was usual in ancient Greek scales.

- In many styles, such as soleá or siguiriya, the melody tends to proceed in contiguous degrees of the scale. Skips of a third or a fourth are rarer. However, in fandangos and fandango-derived styles, fourths and sixths can often be found, especially at the beginning of each line of verse. According to Rossy, this is proof of the more recent creation of this type of songs, influenced by Castilian jota.

Compás

Compás is the Spanish word for metre or time signature (in classical music theory). It also refers to the rhythmic cycle, or layout, of a palo.

The compás is fundamental to flamenco. Compás is most often translated as rhythm but it demands far more precise interpretation than any other Western style of music. If there is no guitarist available, the compás is rendered through hand clapping (palmas) or by hitting a table with the knuckles. The guitarist uses techniques like strumming (rasgueado) or tapping the soundboard (golpe). Changes of chords emphasize the most important downbeats.

Flamenco uses three basic counts or measures: Binary, Ternary and a form of a twelve-beat cycle that is unique to flamenco. There are also free-form styles including, among others, the tonás, saetas, malagueñas, tarantos, and some types of fandangos.

- Rhythms in 2

4 or 4

4. These metres are used in forms like tangos, tientos, gypsy rumba, zambra and tanguillos. - Rhythms in 3

4. These are typical of fandangos and sevillanas, suggesting their origin as non-Roma styles, since the 3

4 and 4

4 measures are not common in ethnic Roma music. - 12-beat rhythms usually rendered in amalgams of 6

8 + 3

4 and sometimes 12

8. The 12-beat cycle is the most common in flamenco, differentiated by the accentuation of the beats in different palos. The accents do not correspond to the classic concept of the downbeat. The alternating of groups of 2 and 3 beats is also common in Spanish folk dances of the 16th Century such as the zarabanda, jácara and canarios.

There are three types of 12-beat rhythms, which vary in their layouts, or use of accentuations: soleá, seguiriya and bulería.

- peteneras and guajiras: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12. Both palos start with the strong accent on 12. Hence the meter is 12 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11...

- The seguiriya, liviana, serrana, toná liviana, cabales: 121 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12.

- soleá, within the cantiñas group of palos which includes the alegrías, cantiñas, mirabras, romera, caracoles and soleá por bulería (also "bulería por soleá"): 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12. For practical reasons, when transferring flamenco guitar music to sheet music, this rhythm is written as a regular 3

4.

The Bulerías is the emblematic palo of flamenco: today its 12-beat cycle is most often played with accents on the 3rd, 6th, 8th, 10th and 12th beats. The accompanying palmas are played in groups of 6 beats, giving rise to a multitude of counter-rhythms and percussive voices within the 12 beat compás.

Forms of flamenco expression

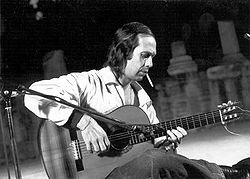

Toque (guitar)

The origins, history and importance of the flamenco guitar is covered in the main Wikipedia entry for the Flamenco guitar.

Cante (song)

The origins, history and importance of the cante is covered in the main Wikipedia entry for the cante flamenco.

Baile (dance)

El baile flamenco[24] is known for its emotional intensity, proud carriage, expressive use of the arms and rhythmic stamping of the feet (often confused[citation needed] with tap dance or Irish dance but with a completely different technique). As with any dance form, many different styles of flamenco have developed.

In the twentieth century, flamenco danced informally at gitano (Roma) celebrations in Spain was considered the most "authentic" form of flamenco. There is less virtuoso technique in gitano flamenco, but the music and steps are fundamentally the same. The arms are noticeably different from classical flamenco, curving around the head and body rather than extending, often with a bent elbow.

"Flamenco puro" is considered the form of performance flamenco closest to its gitano influences. In this style, the dance is always performed solo, and is improvised rather than choreographed. Some purists frown on castanets (even though they can be seen in many early 20th century photos of flamenco dancers).

"Classical flamenco" is the style most frequently performed by Spanish flamenco dance companies, tending to exhibit more clearly the characteristics derived from the Seguidilla, a traditional Spanish dance. It is danced largely in a proud and upright way. For women, the back is often held in a marked back bend. Unlike the more gitano influenced styles, there is little movement of the hips, the body is tightly held and the arms are long, like a ballet dancer. In fact many of the dancers in these companies have trained in ballet as well as flamenco. Flamenco has both influenced and been influenced by ballet, as evidenced by the fusion of the two created by 'La Argentinita' in the early part of the twentieth century and later, by Joaquín Cortés.

In the 1950s Jose Greco was one of the most famous male Flamenco dancers, performing on stage worldwide and on television including the Ed Sullivan Show, and reviving the art almost singlehandedly.

Modern flamenco is a highly technical dance style requiring years of study. The emphasis for both male and female performers is on lightning-fast footwork performed with absolute precision. In addition, the dancer may have to dance while using props such as castanets, shawls and fans.

"Flamenco nuevo" is a recent style in flamenco, characterized by pared-down costumes (the men often dance bare-chested, and the women in plain jersey dresses). Props such as castanets, fans and shawls are rarely used. Dances are choreographed and include influences from other dance styles.

The flamenco most foreigners are familiar with is a style that was developed as a spectacle for tourists. To add variety, group dances are included and even solos are more likely to be choreographed. The frilly, voluminous spotted dresses are derived from a style of dress worn for the Sevillanas at the annual Feria in Seville.

In traditional flamenco, young people are not considered to have the emotional maturity to adequately convey the duende (soul) of the genre. Therefore, unlike other dance forms, where dancers turn professional early to take advantage of youth and strength, many flamenco dancers do not hit their peak until their thirties and will continue to perform into their fifties and beyond.

-

Claudio Castelucho, Flamenco

-

Theatre Flamenco Work Sample

-

José Villegas Cordero, Baile Andaluz

-

John Singer Sargent, Spanish Dancer

- Scenes of flamenco performance in Seville.

See also

- Andalusian Centre of Flamenco

- Concurso de Cante Jondo

- Festival Bienal Flamenco

- Flamenco rumba

- Flamenco rock

- Flamenco shoes

- Latin Grammy Award for Best Flamenco Album

- Kumpanía: Flamenco Los Angeles

- New Flamenco

- Camarón de la Isla

- Paco de Lucia

- David Peña Dorantes

- Niño Josele

- Paco Peña

- Picados

- Sevillanas

- Silverio Franconetti

- Tablao

- Tomatito

- Traje de flamenca

- Maria Pages

- Cristina Hoyos

- Vicente Amigo

References

- ^ Landborn, Adair (2015). Flamenco and Bullfighting: Movement, Passion and Risk in Two Spanish Traditions. Jefferson, NC, USA: McFarland Books. pp. 107–108. Archived from the original on 2015-03-08.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Akombo, David (2016). The Unity of Music and Dance in World Cultures. McFarland Books. pp. 240–241. ISBN 978-0786497157.

- ^ Hayes, Michelle Heffner (2009). Flamenco: Conflicting Histories of the Dance. McFarland Books. pp. 31–37. ISBN 978-0786439232.

- ^ Manuel Ríos Ruiz notes that the development of flamenco is well documented: "the theatre movement of sainetes (one-act plays) and tonadillas, popular song books and song sheets, customs, studies of dances, and toques, perfection, newspapers, graphic documents in paintings and engravings....in continuous evolution together with rhythm, the poetic stanzas, and the ambiance". Ríos Ruiz, Manuel: Ayer y hoy del cante flamenco, Ediciones ISTMO, Tres Cantos (Madrid), 1997, ISBN 84-7090-311-X

- ^ See |3rd meaning of the term flamenco in the Dictionary of the Real Academia Española.

- ^ Machin-Autenrieth, Matthew (April 2015). "Flamenco ¿Algo Nuestro? (Something of Ours?): Music, Regionalism and Political Geography in Andalusia, Spain". Ethnomusicology Forum. 24 (1): 4–27. doi:10.1080/17411912.2014.966852.

- ^ Federico García Lorca (2010), Importancia histórica y artística del primitivo canto andaluz llamado «cante jondo» (PDF), Stockcero

- ^ Mendoza, Gabriela (2011), "Ser flamenco no es una música, es un estilo de vida", El Diario de Hoy, p. 52

- ^ En El Salvador la agrupación Alma Flamenca es considerada la máxima representante y pionera de este movimiento musical. Mendoza, Gabriela (2011), "Ser flamenco no es una música, es un estilo de vida", El Diario de Hoy, p. 52

- ^ El flamenco es declarado Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial de la Humanidad por la Unesco[permanent dead link], Yahoo Noticias, 16 de noviembre de 2010, consultado el mismo día.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "flamenco". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Infante, Blas (2010). Orígenes de lo Flamenco y Secreto del Cante Jondo (1929–1933) (PDF). Consejería de Cultura de la Junta de Andalucía. p. 166.

- ^ Muhammad Ali Herrera (March 2006). "Breve biografía de Blas Infante". Alif Nûn (36). Archived from the original on 2013-04-11.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ana Ruiz (2007). Vibrant Andalusia: The Spice of Life in Southern Spain. Algora. pp. 165 ff. ISBN 978-0-87586-540-9.

- ^ Pohren, Donn E. (2005). The Art of Flamenco. Westport, Connecticut: Bold Strummer. p. 68. ISBN 978-0933224025.

- ^ "Los Palos del Flamenco Distingue los Diferentes Palos del Flamenco". www.flamencoexport.com.

- ^ www.flamenco-events.com. "Flamenco-Events Palos et compas". www.flamenco-events.com. Retrieved 2018-01-30.

- ^ Manuel, Peter (2006). Tenzer, Michael (ed.). Analytical Studies in World Music. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 98.

- ^ Martin, Juan (2002-03-01). Solo Flamenco Guitar. Mel Bay Publications. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-7866-6458-0.

- ^ Manuel, Peter (2006). Tenzer, Michael (ed.). Analytical Studies in World Music. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 96.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-03-08. Retrieved 2006-12-10.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Revista de Folklore". funjdiaz.net. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ^ Koster, Dennis (1 June 2002). Guitar Atlas, Flamenco. Alfred Music Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-7390-2478-2. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ^ "Flamenco show in Seville". Tablao Flamenco El Arenal.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help)

Sources

- Álvarez Caballero, Ángel: El cante flamenco, Alianza Editorial, Madrid, Second edition, 1998. ISBN 84-206-9682-X (First edition: 1994)

- Álvarez Caballero, Ángel: La Discografía ideal del cante flamenco, Planeta, Barcelona, 1995. ISBN 84-08-01602-4

- Arredondo Pérez, Herminia y García Gallardo, Francisco J.: "Música flamenca. Nuevos artistas, antiguas tradiciones" In Andalucía en la música. Expresión de comunidad, construcción de identidad, edited by Francisco J. García y Herminia Arredondo. Sevilla: Centro de Estudios Andaluces, 2014, pp. 225–242. ISBN 978-84-942332-0-3

- Banzi, Julia Lynn (Ph.D.): "Flamenco Guitar Innovation and the Circumscription of Tradition" 2007, 382 pages; AAT 328581, DAI-A 68/10, University of California, Santa Barbara.

- Coelho, Víctor Anand (Editor): "Flamenco Guitar: History, Style, and Context", in The Cambridge Companion to the Guitar, Cambridge University Press, 2003, pp. 13–32.

- Mairena, Antonio & Molina, Ricardo: Mundo y formas del cante flamenco, Librería Al-Ándalus, Third Edition, 1979 (First Edition: Revista de Occidente, 1963)

- Martín Salazar, Jorge: Los cantes flamencos, Diputación Provincial de Granada, Granada, 1991 ISBN 84-7807-041-9

- Manuel, Peter. "Flamenco in Focus: An Analysis of a Performance of Soleares." In Analytical Studies in World Music, edited by Michael Tenzer. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006, pp. 92–119.

- Ortiz Nuevo, José Luis: Alegato contra la pureza, Libros PM, Barcelona, 1996. ISBN 84-88944-07-1

- Ríos Ruiz, Manuel. Ayer y hoy del cante flamenco, Ediciones Istmo, Tres Cantos (Madrid), 1997, ISBN 84-7090-311-X

- Rossy, Hipólito: Teoría del Cante Jondo, Cresda, Barcelona, 1998. ISBN 84-7056-354-8 (First edition: 1966)

- Caba Landa, Pedro y Caba Landa, Carlos. Andalucía, su comunismo y su cante jondo. 1ª Ed Editorial Atlántico 1933. 3ª Edición, Editorial Renacimiento 2008. ISBN 978-84-8472-348-6