Gothic Line

| Gothic Line Offensive | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Italian Campaign of World War II | |||||||

German defensive positions in Northern Italy, 1944 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

U.S. Fifth Army British Eighth Army Brazilian Expeditionary Force |

German 10th Army German 14th Army Army Group Liguria | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 40,000[1] | |||||||

The Gothic Line (Template:Lang-de; Template:Lang-it) was a German defensive line of the Italian Campaign of World War II. It formed Field Marshal Albert Kesselring's last major line of defence along the summits of the northern part of the Apennine Mountains during the fighting retreat of the German forces in Italy against the Allied Armies in Italy, commanded by General Sir Harold Alexander.

Adolf Hitler had concerns about the state of preparation of the Gothic Line: he feared the Allies would use amphibious landings to outflank its defences. To downgrade its importance in the eyes of both friend and foe, he ordered the name, with its historic connotations, changed, reasoning that if the Allies managed to break through they would not be able to use the more impressive name to magnify their victory claims. In response to this order, Kesselring renamed it the "Green Line" (Grüne Linie) in June 1944.

Using more than 15,000 slave-labourers, the Germans created more than 2,000 well-fortified machine gun nests, casemates, bunkers, observation posts and artillery-fighting positions to repel any attempt to breach the Gothic Line.[2] Initially this line was breached during Operation Olive (also sometimes known as the Battle of Rimini), but Kesselring's forces were consistently able to retire in good order. This continued to be the case up to March 1945, with the Gothic Line being breached but with no decisive breakthrough; this would not take place until April 1945 during the final Allied offensive of the Italian Campaign.[3]

Operation Olive has been described as the biggest battle of materials ever fought in Italy. Over 1,200,000 men participated in the battle. The battle took the form of a pincer manoeuvre, carried out by the British Eighth Army and the U.S. Fifth Army against the German 10th Army (10. Armee) and German 14th Army (14. Armee). Rimini, a city which had been hit by previous air raids, had 1,470,000 rounds fired against it by allied land forces. According to Lieutenant-General Oliver Leese, commander of the British Eighth Army:

The battle of Rimini was one of the hardest battles of Eighth Army. The fighting was comparable to El Alamein, Mareth and the Gustav Line (Monte-Cassino).

Background

After the nearly concurrent breakthroughs at Cassino and Anzio in spring 1944, the 11 nations representing the Allies in Italy finally had a chance to trap the Germans in a pincer movement and to realize some of the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill's strategic goals for the long, costly campaign against the Axis "underbelly". This would have required the U.S. Fifth Army under Lieutenant General Mark Clark to commit most of his Anzio forces to the drive east from Cisterna, and to execute the envelopment envisioned in the original planning for the Anzio landing (i.e., flank the German 10th Army, and sever its northbound line of retreat from Cassino). Instead, fearing that the British Eighth Army, under Lieutenant-General Sir Oliver Leese, might beat him to Rome, Clark diverted a large part of his Anzio force in that direction in an attempt to ensure that he and the Fifth Army would have the honour of liberating the Eternal City.

As a result, most of Generalfeldmarschall Kesselring's forces slipped the noose and fell back north fighting delaying actions, notably in late June on the Trasimene Line (running from just south of Ancona on the east coast, past the southern shores of Lake Trasimeno near Perugia and on to the west coast south of Grosseto) and in July on the Arno Line (running from the west coast along the line of the Arno River and into the Apennine Mountains north of Arezzo). This gave time to consolidate the Gothic Line, a 10 mi (16 km) deep belt of fortifications extending from south of La Spezia (on the west coast) to the Foglia Valley, through the natural defensive wall of the Apennines (which ran unbroken nearly from coast to coast, 50 mi (80 km) deep and with high crests and peaks rising to 7,000 ft (2,100 m)), to the Adriatic Sea between Pesaro and Ravenna, on the east coast. The emplacements included numerous concrete-reinforced gun pits and trenches, and 2,376 machine-gun nests with interlocking fire, 479 anti-tank, mortar and assault gun positions, 120,000 m (130,000 yd) of barbed wire and many miles of anti-tank ditches.[4] This last redoubt proved the Germans' determination to continue fighting.

Nevertheless, it was fortunate for the Allies that at this stage of the war the Italian partisan forces had become highly effective in disrupting the German preparations in the high mountains. By September 1944, German generals were no longer able to move freely in the area behind their main lines because of partisan activity. Major General (Generalleutnant) Frido von Senger und Etterlin—commanding XIV Panzer Corps (XIV Panzerkorps)—later wrote that he had taken to travelling in a little Volkswagen "(displaying) no general's insignia of rank — no peaked cap, no gold or red flags...". One of his colleagues who ignored this caution—Brigadier Wilhelm Crisolli (commanding the 20th Luftwaffe Field Division)—was caught and killed by partisans as he returned from a conference at corps headquarters.[5]

Construction of the defences was also hampered by the deliberately poor quality concrete provided by local Italian mills whilst captured partisans forced into the construction gangs supplemented the natural lethargy of forced labour with clever sabotage. Nevertheless, prior to the Allies' attack, Kesselring had declared himself satisfied with the work done, especially on the Adriatic side where he "...contemplated an assault on the left wing....with a certain confidence".[6]

Allied strategy

The Italian front was seen by the Allies to be of secondary importance to the offensives through France, and this was underlined by the withdrawal during the summer of 1944 of seven divisions from the U.S. Fifth Army to take part in the landings in southern France, Operation Dragoon. By 5 August, the strength of the U.S. Fifth Army had fallen from 249,000 to 153,000,[7] and they had only 18 divisions to confront the combined German 10th and 14th Armies′ strength of 14 divisions plus four to seven reserve divisions.

Nevertheless, Winston Churchill and the British Chiefs of Staff were keen to break through the German defences to open up the route to the northeast through the "Ljubljana Gap" into Austria and Hungary. Whilst this would threaten Germany from the rear, Churchill was more concerned to forestall the Russians advancing into central Europe. The U.S. Chiefs of Staff had strongly opposed this strategy as diluting the Allied focus in France. However, following the Allied successes in France during the summer, the U.S. Chiefs relented, and there was complete agreement amongst the Combined Chiefs of Staff at the Second Quebec Conference on 12 September.[8]

Allied plan of attack

General Alexander's original plan—as formulated by his Chief of Staff Lieutenant-General John Harding—was to storm the Gothic Line in the centre, where most of his forces were already concentrated. It was the shortest route to his objective, the plains of Lombardy, and could be mounted quickly. He mounted a deception operation to convince the Germans that the main blow would come on the Adriatic front.

On 4 August, Alexander met Lieutenant-General Oliver Leese, the British Eighth Army commander, to find that Leese did not favour the plan.[9] He argued that the Allies had lost their specialist French mountain troops to Operation Dragoon and that the Eighth Army's strength lay in tactics combining infantry, armour and guns which could not be employed in the high mountains of the central Apennines. It has also been suggested that Leese disliked working in league with Clark after the U.S. Fifth Army's controversial move on Rome at the end of May and early June and wished for the Eighth Army to win the battle on its own.[10] He suggested a surprise attack along the Adriatic coast. Although Harding did not share Leese's view and Eighth Army planning staff had already rejected the idea of an Adriatic offensive (because it would be difficult to bring the necessary concentration of forces to bear), General Alexander was not prepared to force Leese to adopt a plan which was against his inclination and judgement[11] and Harding was persuaded to change his mind.

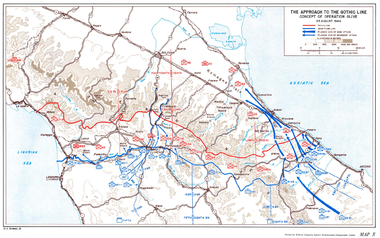

Operation Olive—as the new offensive was christened—called for Leese's Eighth Army to attack up the Adriatic coast toward Pesaro and Rimini and draw in the German reserves from the centre of the country. Clark's Fifth Army would then attack in the weakened central Apennines north of Florence toward Bologna with British XIII Corps on the right wing of the attack fanning toward the coast to create a pincer with the Eighth Army advance. This meant that as a preparatory move, the bulk of Eighth Army had to be transferred from the centre of Italy to the Adriatic coast, taking two valuable weeks, while a new intelligence deception plan (Operation Ulster[12]) was commenced to convince Kesselring that the main attack would be in the centre.

Adriatic front (British Eighth Army)

Eighth Army dispositions for Operation Olive

On the coast, Lieutenant-General Sir Oliver Leese, the British Eighth Army commander, had Polish II Corps with 5th Kresowa Division in the front line and the 3rd Carpathian Division in reserve. To the left of the Poles was Canadian I Corps which had Canadian 1st Infantry Division (with British 21st Tank Brigade under command) in the front line and Canadian 5th Armoured Division in reserve. For the opening phase the Corps artillery was strengthened with the addition of British 4th Infantry Division's artillery. West of the Canadians was V Corps with British 46th Infantry Division manning the right of the Corps front line and 4th Indian Infantry Division its left. In reserve were the British 56th Infantry Division, British 1st Armoured Division, British 7th Armoured Brigade and British 25th Tank Brigade. Further to the rear was the British 4th Division waiting to be called forward to join the Corps. The left flank of the Eighth Army front was guarded by X Corps employing 10th Indian Infantry Division and two armoured car regiments, 12th and 27th Lancers. Prior to the attack the Canadian Corps' front was covered by patrolling Polish cavalry units and V Corps by patrolling elements of the Italian Liberation Corps. In Army reserve, also waiting to be called forward was the 2nd New Zealand Division.[13]

German 10th Army dispositions

Facing the Eighth Army was the German 10th Army′s LXVI Panzer Corps (LXVI Panzerkorps). Initially, this had only three divisions: 1st Parachute Division facing the Poles, 71st Infantry Division (71. Infantriedivision) inland on the parachute division's right and 278th Division (278. Infantriedivision) on the Corps right flank in the hills which was in the process of relieving 5th Mountain Division. The 10th Army had a further five divisions in 51st Mountain Corps covering 80 mi (130 km) of front line on the right of LXVI Panzer Corps and a further two divisions—162nd Infantry Division (162. (Turkoman) Infantriedivision) and 98th Infantry Division (98. Infantriedivision) (replaced by 29th Panzer Division (29. Panzerdivision) from 25 August)—covering the Adriatic coast behind LXVI Corps. In addition, Generalfeldmarschall Kesselring had in his Army Group Reserve the 90th Panzer Grenadier Division (90. Panzergrenadierdivision) and 26th Panzer Division (26. Panzerdivision).[14]

Eighth Army attack

The British Eighth Army crossed the Metauro river and launched its attack against the Gothic Line outposts on 25 August. As Polish II Corps, on the coast, and I Canadian Corps, on the coastal plain on the Poles' left, advanced towards Pesaro the coastal plain narrowed and it was planned that the Polish Corps, weakened by losses and lack of replacements, would go into Army reserve and the front on the coastal plain would become the responsibility of the Canadian Corps alone. The Germans were taken by surprise, to the extent that both von Vietinghoff, and the parachute division's commander—Generalmajor Richard Heidrich—were away on leave.[15] They were in the process of pulling back their forward units to the Green I fortifications of the Gothic Line proper and Kesselring was uncertain whether this was the start of a major offensive or just Eighth Army advancing to occupy vacated ground whilst the main Allied attack would come on the U.S. Fifth Army front towards Bologna. On 27 August, he was still expressing the view that the attack was a diversion and so would not commit reserves to the front.[15] It was not until 28 August—when he saw a captured copy of Leese's order of the day to his army prior to the attack—that Kesselring realised that a major offensive was in progress,[16] and three divisions of reinforcements were ordered from Bologna to the Adriatic front, still needing at least two days to get into position.

By 30 August, the Canadian and British Corps had reached the Green I main defensive positions running along the ridges on the far side of the Foglia river. Taking advantage of the Germans' lack of manpower, the Canadians punched through and by 3 September had advanced a further 15 mi (24 km) to the Green II line of defences running from the coast near Riccione. The Allies were close to breaking through to Rimini and the Romagna plain. However, LXXVI Panzer Corps on the German 10th Army′s left wing had withdrawn in good order behind the line of the Conca river.[17] Fierce resistance from the Corps′ 1st Parachute Division—commanded by Heidrich (supported by intense artillery fire from the Coriano ridge in the hills on the Canadians' left)—brought their advance to a halt.

Meanwhile, British V Corps was finding progress in the more difficult hill terrain with its poor roads tough going. On 3–4 September, while the Canadians once again attacked along the coastal plain, V Corps made an armoured thrust to dislodge the Coriano Ridge defences and reach the Marano river. This was to open the gate to the plain beyond which could be rapidly exploited by the tanks of British 1st Armoured Division, poised for this purpose. However, after two days of gruesome fighting with heavy losses on both sides, the Allies were obliged to call off their assault and reassess their strategy. The Eighth Army commander, Oliver Leese, decided to outflank the Coriano ridge positions by driving westwards toward Croce and Gemmano to reach the Marano valley which curved behind the Coriano positions to the coast some 2 mi (3.2 km) north of Riccione.

Battles for Gemmano and Croce

The Battle of Gemmano has been nicknamed by some historians as the "Cassino of the Adriatic". After 11 assaults between 4 and 13 September (first by British 56th Division and then British 46th Division), it was the turn of Indian 4th Division who after a heavy bombardment made the 12th attack at 03:00 on 15 September and finally carried and secured the German defensive positions.[18] In the meantime, to the north, on the other side of the Conca valley a similarly bloody engagement was being ground out at Croce. The German 98th Division held their positions with great tenacity, and it took five days of constant fighting, often door to door and hand to hand before the British 56th Division captured Croce.

Coriano taken and the advance to Rimini and San Marino

With progress slow at Gemmano, Leese decided to renew the attack on Coriano. After a paralyzing bombardment from 700 artillery pieces[19] and bombers, the Canadian 5th Armoured Division and the British 1st Armoured Division launched their attack on the night of 12 September. The Coriano positions were finally taken on 14 September.

Once again, the way was open to Rimini. Kesselring's forces had taken heavy losses, and three divisions of reinforcements ordered to the Adriatic front would not be available for at least a day. Now, the weather intervened: torrential rain turned the rivers into torrents and halted air support operations. Once again movement ground to a crawl, and the German defenders had the opportunity to reorganise and reinforce their positions on the Marano river, and the salient to the Lombardy plain closed. Once more, the Eighth Army was confronted by an organised line of defence, the Rimini Line.

Meanwhile, with Croce and beyond it Montescudo secured, the left wing of the Eighth Army advanced to the Marano river and the frontier of San Marino. The Germans had occupied neutral San Marino over a week previously to take advantage of the heights on which the city-state stood. By 19 September, the city was isolated and fell to the Allies with relatively little cost.[20] Three miles (5 km) beyond San Marino lay the Marecchia valley running across the Eighth Army line of advance and running to the sea at Rimini.

On the right the Canadian Corps on 20 September broke the German positions on the Ausa river and into the Lombardy Plain and 3rd Greek Mountain Brigade entered Rimini on the morning of 21 September as the Germans withdrew from their positions on the Rimini Line behind the Ausa to new positions on the Marecchia.[21] However, Kesselring's defence had won him time until the onset of the autumn rains. Progress for the Eighth Army became very slow with mud slides caused by the torrential rain making it difficult to keep roads and tracks open, creating a logistical nightmare. Although they were out of the hills, the plains were waterlogged and the Eighth Army found themselves confronted, as they had the previous autumn, by a succession of swollen rivers running across their line of advance.[22] Once again, the conditions prevented Eighth Army's armour from exploiting the breakthrough, and the infantry of British V Corps and I Canadian Corps (joined by the 2nd New Zealand Division) had to grind their way forward while von Vietinghoff withdrew his forces behind the next river beyond the Marecchia, the Uso, a few miles beyond Rimini. The positions on the Uso were forced on 26 September, and Eighth Army reached the next river, the Fiumicino, on 29 September. Four days of heavy rain forced a halt, and by this time V Corps was fought out and required major reorganization.

Since the start of Operation Olive, Eighth Army had suffered 14,000 casualties.[nb 1] As a result, British battalions had to be reduced from four to three rifle companies due to a severe shortage of manpower. Facing the Eighth Army LXXVI Panzer Corps had suffered 16,000 casualties.[24] As the Eighth Army paused at the end of September to reorganise Leese was reassigned to command the Allied land forces in South-East Asia, and Lieutenant-General Richard L. McCreery was moved from commanding British X Corps to take over the army command.[25]

Central Front (Fifth Army)

U.S. Fifth Army formation

Lieutenant General Mark Clark's U.S. Fifth Army comprised three corps: U.S. IV Corps on the left formed by U.S. 1st Armored Division, 6th South African Armoured Division and two regimental Combat Teams ("RCT"), one of the U.S. 92nd Infantry Division (the "Buffalo Soldiers") the other the Brazilian 6th RCT (the first land forces contingent of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force); in the centre was U.S. II Corps (U.S. 34th, 85th, 88th and 91st Infantry Divisions supported by three tank battalions); and on the right British XIII Corps (British 1st Infantry Division, British 6th Armoured Division, 8th Indian Infantry Division and 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade). Like the Eighth Army, the Fifth Army was considered to be strong in armour and short on infantry considering the terrain they were attacking.[26]

German formation in the central Apennines

In the front line facing Clark's forces were five divisions of Joachim Lemelsen's German 14th Army (20th Luftwaffe Field Division, 16th SS Panzer Grenadier Division (16. Panzergrenadierdivision), 65th and 362nd Infantry Divisions and the 4th Parachute Division) and two divisions on the western end of Heinrich von Vietinghoff's German 10th Army (356th and 715th Infantry Divisions). By the end of the first week in September, the Luftwaffe Field Division and the 356th Infantry Division had been moved to the Adriatic front along with (from army reserve) the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division and the armoured reserve of 26th Panzer Division. The 14th Army was not of the same quality as the 10th Army: it had been badly mauled in the retreat from Anzio and some of its replacements had been hastily and inadequately trained.[27]

Allied plan

Clark's plan was for II Corps to strike along the road from Florence to Firenzuola and Imola through the Il Giogo pass to outflank the formidable defences of the Futa pass (on the main Florence–Bologna road) while on their right British XIII Corps would advance through the Gothic Line to cut Route 9 (and therefore Kesselring's lateral communications) at Faenza. The transfer of 356th Infantry Division to the Adriatic weakened the defences around the Il Giogo pass which was already potentially an area of weakness, being on the boundary between 10th and 14th Armies.[28]

Battle

During the last week in August, U.S. II Corps and British XIII Corps started to move into the mountains to take up positions for the main assault on the main Gothic Line defences. Some fierce resistance was met from outposts but at the end of the first week in September, once reorganisation had taken place following the withdrawal of three divisions to reinforce the pressured Adriatic front, the Germans withdrew to the main Gothic Line defences. After an artillery bombardment, the Fifth Army's main assault began at dusk on 12 September.

Progress at the II Giogo pass was slow, but on II Corps' right British XIII Corps were making better progress. Clark grasped this opportunity to divert part of II Corps reserve (the 337th Infantry Regiment, part of the 85th Infantry Division) to exploit XIII Corps success. Attacking on 17 September, supported by both American and British artillery, the infantry fought their way onto Monte Pratone, some 2–3 mi (3.2–4.8 km) east of the Il Giogo pass and a key position on the Gothic Line.[29] Meanwhile, U.S. II Corps renewed their assault on Monte Altuzzo, dominating the east side of the Il Giogo pass. The Altuzzo positions fell on the morning of 17 September, after five days of fighting. The capture of Altuzzo and Pratone as well as Monte Verruca between them caused the formidable Futa pass defences to be outflanked, and Lemelsen was forced to pull back, leaving the pass to be taken after only light fighting on 22 September.

On the left, IV Corps had fought their way to the main Gothic Line: notably the U.S. 370th Regimental Combat Team, which pushed the Axis troops on its sector to the north beyond the Highway 12 towards Gallicano; and the Brazilian 6th RCT, which took Massarosa, Camaiore and other small towns on its own way north. By the end of month, the Brazilian unit had conquered Monte Prano and controlled the Serchio valley region without suffering any major casualties. In October, it also took Fornaci with its munitions factory, and Barga; while the 370th received reinforcements from other Buffalo soldiers units (365th and 371st), to ensure the Fifth Army left wing sector at the Ligurian Sea.[30][31]

On Fifth Army's far right wing, on the right of the British XIII Corps front, 8th Indian Infantry Division fighting across trackless ground had captured the heights of Femina Morta, and British 6th Armoured Division had taken the San Godenzo Pass on Route 67 to Forlì, both on 18 September.

At this stage, with the slow progress on the Adriatic front, Clark decided that Bologna would be too far west along Route 9 to trap the German 10th Army. He decided therefore to make the main II Corps thrust further east towards Imola whilst XIII Corps would continue to push on the right toward Faenza. Although they were through the Gothic Line, Fifth Army—just like the Eighth Army before them—found the terrain beyond and its defenders even more difficult. Between 21 September and 3 October, U.S. 88th Division had fought its way to a standstill on the route to Imola suffering 2,105 men killed and wounded — roughly the same as the whole of the rest of II Corps during the actual breaching of the Gothic Line.[32]

The fighting toward Imola had drawn German troops from the defence of Bologna, and Clark decided to switch his main thrust back toward the Bologna axis. U.S. II Corps pushed steadily through the Raticosa Pass and by 2 October, it had reached Monghidoro some 20 mi (32 km) from Bologna. However, as it had on the Adriatic coast, the weather had broken and rain and low cloud prevented air support while the roads back to the ever more distant supply dumps near Florence became morasses.[33]

On 5 October, U.S. II Corps renewed its offensive along a 14-mile (23 km) front straddling Route 65 to Bologna. They were supported on their right flank by British XIII Corps including British 78th Infantry Division, newly returned to Italy after a three-month re-fit in Egypt. Gradual progress was made against stiffening opposition as German 14th Army moved troops from the quieter sector opposite U.S. IV Corps. By 9 October, they were attacking the massive 1,500 foot (450 m) high sheer escarpment behind Livergnano which appeared insuperable. However, the weather cleared on the morning of 10 October to allow artillery and air support to be brought to bear. Nevertheless, it took until the end of 15 October before the escarpment was secured.[34] On the right of U.S. II Corps British XIII Corps was experiencing equally determined fighting on terrain just as difficult.

Time runs out for the Allies

By the second half of October, it was becoming increasingly clear to General Alexander that despite the dogged fighting in the waterlogged plain of Romagna and the streaming mountains of the central Apennines, with the autumn well advanced and exhaustion and combat losses increasingly affecting his forces' capabilities, no breakthrough was going to occur before the winter weather returned.

On the Adriatic front, the British Eighth Army's advance resumed on its left wing through the Apennine foothills toward Forlì on Route 9. On 5 October the 10th Indian Infantry Division—switched from British X Corps to British V Corps—had crossed the Fiumicino river (thought to be river known in Roman times as the Rubicon) high in the hills and turned the German defensive line on the river forcing the German 10th Army units downstream to pull back towards Bologna. Paradoxically, in one sense, this helped Kesselring because it shortened the front he had to defend and shortened the distance between his two armies, providing him with greater flexibility to switch units between the two fronts. Continuing their push up Route 9, on 21 October British V Corps crossed the Savio river which runs north eastward through Cesena to the Adriatic and by 25 October were closing on the Ronco river, some 10 mi (16 km) beyond the Savio, behind which the Germans had withdrawn. By the end of the month, the advance had reached Forlì, halfway between Rimini and Bologna.

Cutting the German Armies' lateral communications remained a key objective. Indeed, later Kesselring was to say that if in mid-October the front south of Bologna could not be held, then all the German positions east of Bologna "were automatically gone.".[35] Alexander and Clark had decided therefore to make a last push for Bologna before winter gripped the front.

On 16 October, the U.S. Fifth Army had gathered itself for one last effort to take Bologna. The Allied Armies in Italy were short of artillery ammunition because of a global reduction in Allied ammunition production in anticipation of the final defeat of Germany. The Fifth Army′s batteries were rationed to such an extent that the total rounds fired in the last week of October were less than the amount fired during one eight-hour period on 2 October.[36] Nevertheless, U.S. II Corps and British XIII Corps pounded away for the next 11 days. Little progress was made in the centre along the main road to Bologna. On the right, there was better progress, and on 20 October the U.S. 88th Division seized Monte Grande, only 4 mi (6.4 km) from Route 9, and three days later British 78th Division stormed Monte Spaduro. However, the remaining four miles were over difficult terrain and were reinforced by three of the best German divisions in Italy—the 29th Panzergrenadier Division, 90th Panzergrenadier Division and the 1st Parachute Division—which Kesselring had been able to withdraw from the Romagna as a result of his shortened front. By late October, the Brazilian 6th Regimental Combat Team had pushed the Axis forces through province of Lucca to Barga, where its advance was halted.[37]

Aftermath

In early November, the buildup to full strength of the 1st Brazilian Division and some reinforcement of the U.S. 92nd Division had not nearly compensated the U.S. Fifth Army for the formations diverted to France. The situation in the British Eighth Army was even worse: Replacement cadres were being diverted to northern Europe and I Canadian Corps was ordered to prepare to ship to the Netherlands in February of the following year.[38] Also, while they remained held in the mountains, the armies continued to have an over-preponderance of armour relative to infantry.[39]

During November and December, Fifth Army concentrated on dislodging the Germans from their well-placed artillery positions which had been key in preventing the Allied advance towards Bologna and Po Valley. Using small and medium Brazilian and American forces, U.S. Fifth Army attacked these points one by one but with no positive outcome. By the end of the year, the defence compound formed by the Germans around Monte Castello, (Lizano in) Belvedere, Della Toraccia, Castelnuovo (di Vergato), Torre di Nerone, La Serra, Soprassasso and Castel D'Aiano had proved extremely resiliant.[40][41]

Meanwhile, the British Eighth Army—held on Route 9 at Forlì—continued a subsidiary drive up the Adriatic coast and captured Ravenna on 5 November. In early November, the push up Route 9 resumed, and the river Montone, just beyond Forlì, was crossed on 9 November. However, the going continued to be very tough with the river Cosina, some 3 mi (4.8 km) further along Route 9 being crossed only on 23 November. By 17 December, the river Lamone had been assaulted and Faenza cleared.[42] The German 10th Army established itself on the raised banks of the river Senio (rising at least 20 ft (6.1 m) above the surrounding plain) which ran across the line of the Eighth Army advance just beyond Faenza down to the Adriatic north of Ravenna. With snows falling and winter firmly established, any attempt to cross the Senio was out of the question and the Eighth Army's 1944 campaign came to an end.[43]

In late December, in a final flourish to the year's fighting, the Germans used a predominantly Italian force of units from the Italian Monterosa Division to attack the left wing of the U.S. Fifth Army in the Serchio valley in front of Lucca to pin Allied units there which might otherwise have been switched to the central front (the Battle of Garfagnana). Two brigades of the 8th Indian Infantry Division were rapidly switched across the Apennines to reinforce the U.S. 92nd Infantry Division. By the time the reinforcements had arrived, the Axis forces had broken through to capture Barga, but decisive action by the 8th Indian Division's Major-General Dudley Russell halted further advance and the situation was stabilised and Barga recaptured by the New Year.[44]

In mid-December Harold Alexander became supreme commander of the Mediterranean Theatre. Mark Clark took his place as commander of the Allied Armies in Italy (re-designated 15th Army Group) and command of U.S. Fifth Army was given to Lucian K. Truscott.[45] In mid-February, as the winter weather improved, Fifth Army resumed its attacks on German artillery positions (Operation Encore). This time the IV Corps used full two infantry divisions to accomplish the mission: the Brazilian division, tasked with taking Monte Castello, Soprassasso and Castelnuovo di Vergato; and the newly arrived U.S. 10th Mountain Division, tasked to take Belvedere, Della Torraccia and Castel D'Aiano.[46][47] Operation Encore began on 18 February and was completed on 5 March, preparatory to the final offensive.[48][49][50]

See also

- Gothic Line order of battle

- Battle of Rimini (1944)

- Italian Campaign (World War II)

- Mediterranean and Middle East theatre of World War II

- Italian Social Republic

- European Theatre of World War II

Notes

- Footnotes

- ^ The British Official History gives V Corps casualties as 9,000 and Canadian casualties (referencing the Canadian Official History) as just under 4,000 up to 21 September. In addition, losses to sickness in V Corps were 6,000 and 1,000 in 1st Canadian Division with no figure given for Canadian 5th Armoured Division.[23] Leese reported battle casualties totaling 14,000 and 210 irrecoverable tanks.[23]

- Citations

- ^ The lost evidence- Monte Cassino- history channel[verification needed]

- ^ Sterner, 2008. p.106

- ^ Bryn, Chapter 14.

- ^ Orgill, p. 28.

- ^ Orgill, p. 36.

- ^ Orgill, p. 29.

- ^ Orgill, p. 20.

- ^ Orgill, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Jackson, p. 119.

- ^ Blaxland, p. 163.

- ^ Orgill, p. 33.

- ^ Jackson, p. 126.

- ^ Jackson, p. 226.

- ^ Jackson, p. 227.

- ^ a b Jackson, p. 234.

- ^ Orgill, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Orgill, p. 65.

- ^ Hingston, p. 129.

- ^ Orgill, p. 124.

- ^ Orgill, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Jackson, p. 296.

- ^ Orgill, p. 161.

- ^ a b Jackson 2004, p. 303.

- ^ Jackson, p.304.

- ^ Carver, p. 243.

- ^ Orgill, p. 164.

- ^ Orgill, pp. 164–166.

- ^ Orgill, p.165.

- ^ Orgill, p. 178.

- ^ Brooks, pp. 221 & 223.

- ^ Moraes, Chapter III, section "Operations at Serchio Valley".

- ^ Orgill, p. 187.

- ^ Orgill, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Orgill, p. 200.

- ^ Orgill, p. 210.

- ^ Orgill, p. 213.

- ^ Brooks, pp. 223-24.

- ^ Corrigan 2010, p.523

- ^ Clark, p.606

- ^ Moraes, Chapter IV

- ^ Brooks, Chapters XX & XXI

- ^ Blaxland, pp. 227–236.

- ^ Carver, pp. 266–267.

- ^ Moseley, Ray (2004). Mussolini : the last 600 days of il Duce. Dallas: Taylor Trade Pub. ISBN 978-1-58979-095-7. p. 156

- ^ Sterner, p.105

- ^ Brooks, Chapters XXI & XX.

- ^ Moraes, Chapter V (The IV Corps Offensive); Sections Monte Castello & Castelnuovo

- ^ Clark, p.608 View on Google Books

- ^ Bohmler, Chapter IX

- ^ Ibidem, Brooks.

References

- Baumgardner, Randy W. (1998) 10th Mountain Division Turner Publishing Co. ISBN 978-1-56311-430-4

- Blaxland, Gregory (1979). Alexander's Generals (the Italian Campaign 1944–1945). London: William Kimber & Co. ISBN 0-7183-0386-5.

- Bohmler, Rudolf (1964). Monte Cassino: a German View. Cassell. ASIN B000MMKAYM.

- Brooks, Thomas R. (2003) [1996]. The War North of Rome (June 1944 – May 1945). Cambridge, Mass.: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81256-9.

- Carver, Field Marshal Lord (2001). The Imperial War Museum Book of the War in Italy 1943–1945. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 0-330-48230-0.

- Clark, Mark (2007) [1950]. Calculated Risk. New York: Enigma Books. ISBN 978-1-929631-59-9.

- Corrigan, Gordon. (2010) The Second World War: A Military History Atlantic Books ISBN 9781843548942

- Ernest F. Fisher, Jr. (1993) [1977] Mediterranean Theater of Operations: Cassino to the Alps United States Government Printing Office ISBN 9780160613104

- Evans, Bryn. (2012) [1988] With the East Surreys in Tunisia and Italy 1942 - 1945: Fighting for Every River and Mountain Pen & Sword Books Ltd ISBN 9781848847620

- Gibran, Daniel K. (2001) The 92nd Infantry Division and the Italian Campaign in World War II McFarland & Co. Inc. Publishers ISBN 0786410094

- Hingston, W.G. (1946). The Tiger Triumphs: The Story of Three Great Divisions in Italy. HMSO for the Government of India. OCLC 29051302.

- Hoyt, Edwin P. (2007) [2002]. Backwater War. The Allied Campaign in Italy, 1943–45. Mechanicsburg PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3382-3.

- Jackson, General Sir William; Gleave, Group Captain T.P. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO:1987]. Butler, Sir James (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East, Volume VI: Victory in the Mediterranean, Part 2 – June to October 1944. History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Uckfield, UK: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 1-84574-071-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Laurie, Clayton D. (1994). Rome-Arno 22 January-9 September 1944. WWII Campaigns. United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 978-0-16-042085-6. CMH Pub 72-20.

- Moraes, Mascarenhas (1966). The Brazilian Expeditionary Force By Its Commander. US Government Printing Office. ASIN B000PIBXCG.

- Montemaggi, Amedeo (2002). LINEA GOTICA 1944. La battaglia di Rimini e lo sbarco in Grecia decisivi per l'Europa sud-orientale e il Mediterraneo. Rimini: Museo dell'Aviazione.

- Montemaggi, Amedeo (2006). LINEA GOTICA 1944: scontro di civiltà. Rimini: Museo dell'Aviazione.

- Montemaggi, Amedeo (2008). CLAUSEWITZ SULLA LINEA GOTICA. Imola: Angelini Editore.

- Montemaggi, Amedeo (2010). ITINERARI DELLA LINEA GOTICA 1944. Guida storico iconografica ai campi di battaglia. Rimini: Museo dell'Aviazione.

- Muhm, Gerhard. "German Tactics in the Italian Campaign".

- Muhm, Gerhard (1993). La Tattica tedesca nella Campagna d'Italia, in Linea Gotica avanposto dei Balcani (in Italian) (Edizioni Civitas ed.). Roma: (Hrsg.) Amedeo Montemaggi.

- Oland, Dwight D. (1996). North Apennines 1944–1945. WWII Campaigns. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 72-34 ISBN 9781249453659 (of BiblioBazaar, 2012 Reprint).

- O'Reilly, Charles T. (2001). Forgotten Battles: Italy's War of Liberation, 1943-1945. Lexington Books. ISBN 0739101951.

- Orgill, Douglas (1967). The Gothic Line (The Autumn Campaign in Italy 1944). London: Heinemann.

- Popa, Thomas A. (1996). Po Valley 1945. U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 0-16-048134-1. CMH Pub 72-33.

- Sterner, C.Douglas. (2008). Go for Broke. American Legacy Historical Press. ISBN 9780979689611.

- Various Authors (2005) Gothic Line - Le Battaglie Della Linea Gotica 1944-45 Template:It icon / Template:En icon Edizioni Multigraphic ISBN 8874650957

External links

- La Città Invisibile Template:It icon Collection of signs, stories and memories during the Gothic Line age.

- Gemmano 1944 Part 1 : The Gothic Line and the Operation Olive

- Gothic Line And Po Valley Campaign Go For Broke National Education Center

- The Gothic Line: Canada's Month of Hell Canada at War

- Gotica Toscana Italian military history association Template:En icon / Template:It icon

- Men at war on Gothic line Template:It icon / Template:En icon Associazione Linea Gotica

- Montemaggi, Amedeo (2002). "Battle of Rimini". Centro Internazionale Documentazione "Linea Gotica" website. Retrieved 2008-11-20.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - North Apennines Campaign, 1944-1945 in U.S. Army Center of Military History Website.

- Photographs of the Gothic Line Associazione Nazionale Partigiani d'Italia Template:It icon

- Portal FEB Template:Pt icon Website with Bibliography, videos, testimonials from veterans about the Italian Campaign.

- [1] Time Line of Mediterranean WWII theatre Template:It icon