History of Virginia: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 50.89.55.197 (talk) to last revision by Aodhdubh (HG) |

|||

| Line 240: | Line 240: | ||

The Baptists and Presbyterians were subject to many legal constraints and faced growing persecution; between 1768 and 1774 about half of the Baptists ministers in Virginia were jailed for preaching. At the start of the Revolution, however, the Anglican Patriots realized that they needed dissenter support for effective wartime mobilization, so they met most of the dissenters' demands for the freedom to practice their religion in return for their support of the war effort.<ref>John A. Ragosta, "Fighting for Freedom: Virginia Dissenters' Struggle for Religious Liberty during the American Revolution," ''Virginia Magazine of History and Biography,'' 2008, Vol. 116 Issue 3, pp 226-261</ref> |

The Baptists and Presbyterians were subject to many legal constraints and faced growing persecution; between 1768 and 1774 about half of the Baptists ministers in Virginia were jailed for preaching. At the start of the Revolution, however, the Anglican Patriots realized that they needed dissenter support for effective wartime mobilization, so they met most of the dissenters' demands for the freedom to practice their religion in return for their support of the war effort.<ref>John A. Ragosta, "Fighting for Freedom: Virginia Dissenters' Struggle for Religious Liberty during the American Revolution," ''Virginia Magazine of History and Biography,'' 2008, Vol. 116 Issue 3, pp 226-261</ref> |

||

After the victory at Yorktown, the Anglican establishment sought to reintroduce state support for religion. This effort failed when non-Anglicans gave their full support to Thomas Jefferson's Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom, which became law in 1786. With [[Freedom of religion]] the new watchword, the Church of England was dis-established in Virginia. Most ministers were Loyalists and returned to England. When possible, worship continued in the usual fashion, but the local vestry was no longer the recipient of tax money and no longer had local government functions such as poor relief. The [[James Madison (Episcopal Bishop)|Right Reverend James Madison]] (1749–1812), a cousin of Patriot [[James Madison]], was appointed in 1790 as the first [[Episcopal Diocese of Virginia|Episcopal Bishop of Virginia]] and slowly rebuilt the denomination<ref>Thomas E. Buckley, ''Church and state in Revolutionary Virginia, 1776-1787'' (1977)</ref> |

After the victory at Yorktown, the Anglican establishment sought to reintroduce state support for religion. This effort failed when non-Anglicans gave their full support to Thomas Jefferson's Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom, which became law in 1786. With [[Freedom of religion]] the new watchword, the Church of England was dis-established in Virginia. Most ministers were Loyalists and returned to England. When possible, worship continued in the usual fashion, but the local vestry was no longer the recipient of tax money and no longer had local government functions such as poor relief. The [[James Madison (Episcopal Bishop)|Right Reverend James Madison]] (1749–1812), a cousin of Patriot [[James Madison]], was appointed in 1790 as the first [[Episcopal Diocese of Virginia|Episcopal Bishop of Virginia]] and slowly rebuilt the denomination<ref>Thomas E. Buckley, ''Church and state in Revolutionary Virginia, 1776-1787 CRAP Crap'' (1977)</ref> |

||

==American Revolution== |

==American Revolution== |

||

Revision as of 18:30, 6 October 2011

The history of Virginia began with settlement of the geographic region now known as the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States thousands of years ago by Native Americans. Permanent European settlement began with the establishment of Jamestown in 1607, by English colonists. As tobacco emerged as a profitable export, Virginia imported thousands of African laborers to cultivate it. Gradually the colony hardened the boundaries of slavery, raising insurmountable legal barriers between the black slaves and the white population, which did not extend to white males taking sexual advantage of slave women.[1][clarification needed] The Virginia Colony became the wealthiest and most populated British colony in North America. Although elections were democratic, the colony was dominated by elite planters, who also controlled the local Anglican Church. Common planters, yeomen farmers and artisans in the 18th century tended to join the Baptist and Methodist churches after the Great Awakening, a trend that deepened in the 19th century and led to more democracy and social equality. A quarter of the population comprised slaves, most of whom worked the labor-intensive tobacco plantations.

Virginia leaders (together with those of Massachusetts) had a major role in the road to winning independence, with Thomas Jefferson's writing the Declaration of Independence and George Washington's commanding the American army. Washington captured the main British army at Yorktown, Virginia in 1781 to win the American Revolutionary War. The state produced more national leaders than any other, including four of the first five presidents: Washington, Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe. After the Revolution and with the weakening of the tobacco economy, some planters manumitted slaves, bringing the number of free blacks in the state from a few thousand before the Revolution up to 13,000 in 1790 and 20,000 in 1800.[2] With the invention of the cotton gin and expansion of that commodity crop in the Deep South after the Revolution, Virginia slaveholders broke up many families to sell prime slaves in the domestic slave trade.

In 1861, Virginia was a slave state but refused to join the cotton states in the new Confederacy until Lincoln called for troops to confront the seceding states. Then it seceded and Richmond became the new Confederate capital. Because the Confederacy needed to defend Richmond in order to maintain its legitimacy as an independent nation, Virginia became the main target of Union attacks and the major theater of the American Civil War. Unionists in western Virginia resisted secession in 1861, declared the state offices vacant, and elected new state officers. They were recognized by Washington as the Restored government of Virginia. In 1863 West Virginia became a separate state. Richmond fell in April 1865, effectively ending the Civil War. The slaves were emancipated and were aided by the new Freedman's Bureau and civil rights laws passed by Congress.

With thousands of small skirmishes and many large campaigns fought on its soil, Virginia's economy was devastated. The lucrative slave trade was ended. The Piedmont had mixed farming, but a dependence on tobacco farming kept the economy weak. The growth of the cigarette industry late in the century was the first sign of industrialization.[3] After Reconstruction, conservative white Democrats regained power in the state government, where they passed Jim Crow laws, segregated public facilities, and made blacks second-class citizens. In 1900 they passed a constitution that effectively disfranchised blacks, a situation that persisted until federal legislation of the 1960s.

The state was dominated by the "Byrd machine" of conservative rural Democrats from the 1920s to the 1960s. The long struggle by African Americans to have their rights as citizens enforced was worked through education, litigation and nonviolent activism, deep into the 1960s. The US Congress passed federal civil rights legislation in 1964 and 1965 to establish equality under the law, end public segregation and protect citizens' voting rights.

After World War II, the state's economy began to thrive, with a new industrial and urban base. Since the late twentieth century, the agricultural base has lost its preeminence. The contemporary economy includes many new professional and high-tech industries, consultants and defense-related businesses employing highly educated people, especially in Northern Virginia, in association with the federal government. This change in demographic has disrupted the traditional conservative rural base, making for closely divided voting in national elections but still generally conservative state politics.

Native Americans

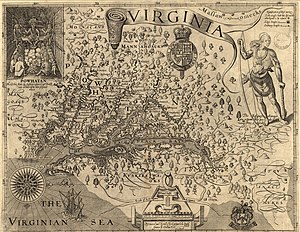

The portion of the New World designated Virginia had been inhabited for thousands of years by varying cultures of indigenous peoples. Archaeological and historical research by anthropologist Helen Rountree and others has established 3,000 years of settlement in much of the Tidewater. Recent archaeological work at Pocahontas Island has revealed prehistoric habitation dating to about 6500 BCE.[5]

At the end of the 16th century, Native Americans living in what is now Virginia were part of three major groups, based chiefly on language families. The largest group, known as the Algonquian, numbered over 10,000 and occupied most of the coastal area up to the fall line. Groups to the interior were the Iroquoian (numbering 2,500) and the Siouan. Tribes included the Algonquian Chesepian, Chickahominy, Doeg, Mattaponi, Nansemond, Pamunkey, Pohick, Powhatan, and Rappahannock; the Siouan Monacan and Saponi; and the Iroquoian-speaking Cherokee, Meherrin, Nottoway, and Tuscarora.[6]

When the first English settlers arrived at Jamestown in 1607, Algonquian tribes controlled most of Virginia east of the fall line. Nearly all were united in what has been historically called the Powhatan Confederacy. Researcher Rountree has noted that empire more accurately describes their political structure. In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, a Chief named Wahunsunacock created this powerful empire by conquering or affiliating with approximately 30 tribes whose territories covered much of eastern Virginia. Known as the Powhatan, or paramount chief, he called this area Tenakomakah ("densely inhabited Land").[7] The empire was advantageous to some tribes, who were periodically threatened by other Native Americans, such as the Monacan.

The Native Americans had a different culture than the English. Despite some successful interaction, issues of ownership and control of land and other resources, and trust between the peoples, became areas of conflict. Virginia has drought conditions an average of every three years. The colonists did not understand that the natives were ill-prepared to feed them during hard times. In the years after 1612, the colonists cleared land to farm export tobacco, their crucial cash crop. As tobacco exhausted the soil, the settlers continually needed to clear more land for replacement. This reduced the wooded land which Native Americans depended on for hunting to supplement their food crops. As more colonists arrived, they wanted more land.

The tribes tried to fight the encroachment by the colonists. Major conflicts took place in the Indian massacre of 1622 and the war of 1644, both under the leadership of the late Chief Powhatan's younger brother, Chief Opechancanough. By the mid-17th century, the Powhatan and allied tribes were in serious decline in population, due in large part to epidemics of newly introduced infectious diseases, such as smallpox and measles, to which they had no natural immunity. The European colonists had expanded territory so that they controlled virtually all the land east of the fall line on the James River. Fifty years earlier, this territory had been the empire of the mighty Powhatan Confederacy.

Surviving members of many tribes assimilated into the general population of the colony. Some retained small communities with more traditional identity and heritage. In the 21st century, the Pamunkey and Mattaponi are the only two tribes to maintain reservations originally assigned under the English. As of 2010, the state has recognized eleven Virginia Indian tribes. Others have renewed interest in seeking state and Federal recognition since the celebration of the 400th anniversary of Jamestown in 2007. State celebrations gave Native American tribes prominent formal roles to showcase their contributions to the state.

Early European exploration

After their discovery of the New World in the 15th century, European states began trying to establish New World colonies. England, the Dutch Republic, France, Portugal, and Spain were the most active.

A Spanish exploration party had come to the lower Chesapeake Bay region of Virginia about 1560. In 1570, the Jesuits planned the Ajacan Mission on the lower peninsula. However, in 1571 it was destroyed by Indians, and the Spanish ended their efforts in Virginia.[8]

In 1584 Sir Walter Raleigh sent Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe to explore what is now the North Carolina coast, and they returned with word of a regional "king" named Wingina, who ruled a land supposedly called Wingandacoa. The latter word was modified later that year by the Queen to "Virginia", perhaps in part noting her status as the "Virgin Queen." On the next voyage, Raleigh was to learn that, while the chief of the Secotans was indeed called Wingina, the expression wingandacoa heard by the English upon arrival actually meant "What good clothes you wear!" in Carolina Algonquian, and was not the name of the country as previously misunderstood.

Virginia is the oldest surviving English place-name in the U.S. not wholly borrowed from a Native American word, and the fourth oldest surviving English place name, though it is Latin in form.[9]

Roanoke Island

The Roanoke Colony was the first English colony in the New World. It was founded at Roanoke Island in what was then Virginia, and is now part of Dare County in the state of North Carolina. Between 1584 and 1587, there were two major groups of settlers sponsored by Sir Walter Raleigh who attempted to establish a permanent settlement at Roanoke Island, and each failed. The final group disappeared completely after supplies from England were delayed three years by a war with Spain. Because they disappeared, they were called "The Lost Colony."

Virginia Company of London

After the death of Queen Elizabeth I, in 1603 King James I assumed the throne of England. After years of war, England was strapped for funds, so he granted responsibility for England's New World colonization to the Virginia Company, which became incorporated as a joint stock company by a proprietary charter drawn up in 1606. There were two competing branches of the Virginia Company and each hoped to establish a colony in Virginia in order to exploit gold (which the region did not actually have), to establish a base of support for English privateering against Spanish ships, and to spread Protestantism to the New World in competition with Spain's spread of Catholicism. Within the Virginia Company, the Plymouth Company branch was assigned a northern portion of the area known as Virginia, and the London Company area to the south.

Jamestown

First landing

In December, 1606, the London Company dispatched a group of 104 colonists in three ships: the Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery, under the command of Captain Christopher Newport. After a long, rough voyage of 144 days, the colonists finally arrived in Virginia on April 26, 1607 at the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay. At Cape Henry, they went ashore, erected a cross, and did a small amount of exploring, an event which came to be called the "First Landing."

Under orders from London to seek a more inland location safe from Spanish raids, they explored the Hampton Roads area and sailed up the newly christened James River to the fall line at what would later became the cities of Richmond and Manchester.

Settlement

After weeks of exploration, the colonists selected a location and founded Jamestown on May 14, 1607. It was named in honor of King James I (as was the river). However, while the location at Jamestown Island was favorable for defense against foreign ships, the low and marshy terrain was harsh and inhospitable for a settlement. It lacked drinking water, access to game for hunting, or much space for farming. While it seemed favorable that it was not inhabited by the Native Americans, within a short time, the colonists were attacked by members of the local Paspahegh tribe.

The colonists arrived ill-prepared to become self-sufficient. They had planned on trading with the Native Americans for food, were dependent upon periodic supplies from England, and had planned to spend some of their time seeking gold. Leaving the Discovery behind for their use, Captain Newport returned to England with the Susan Constant and the Godspeed, and came back twice during 1608 with the First Supply and Second Supply missions. Trading and relations with the Native Americans was tenuous at best, and many of the colonists died from disease, starvation, and conflicts with the Natives. After several failed leaders, Captain John Smith took charge of the settlement, and many credit him with sustaining the colony during its first years, as he had some success in trading for food and leading the discouraged colonists.

After Smith's return to England in August 1609, there was a long delay in the scheduled arrival of supplies. During the winter of 1609-10 and continuing into the spring and early summer, no more ships arrived. The colonists faced what became known as the "starving time". When the new governor Sir Thomas Gates, finally arrived at Jamestown on May 23, 1610, along with other survivors of the wreck of the Sea Venture that resulted in Bermuda being added to the territory of Virginia, he discovered over 80% of the 500 colonists had died; many of the survivors were sick.

Back in England, the Virginia Company was reorganized under its Second Charter, ratified on May 23, 1609, which gave most leadership authority of the colony to the governor, the newly-appointed Thomas West, 3rd Baron De La Warr. In June 1610, he arrived with 150 men and ample supplies. De La Warr began the First Anglo-Powhatan War, against the natives. Under his leadership, Samuel Argall kidnapped Pocahontas, daughter of the Powhatan chief, and held her at Henricus.

The economy of the Colony was another problem. Gold had never been found, and efforts to introduce profitable industries in the colony had all failed until John Rolfe introduced his two foreign types of tobacco: Orinoco and Sweet Scented. These produced a better crop than the local variety and with the first shipment to England in 1612, the customers enjoyed the flavor, thus making tobacco a cash crop that established Virginia's economic viability.

The First Anglo-Powhatan War ended when Rolfe married Pocahontas in 1614; peace was established.

Plantation beginnings

| Dates | Population | New arrivals |

|---|---|---|

| Easter, 1619 | ~1,000 | |

| Easter, 1620 | 866 | |

| 1620–1621 | +1,051 | |

| Easter 1621 | 843 | |

| 1620–1624 | + ~4,000 | |

| Feb. 1624 | 1,277 | |

|

During this time, perhaps 5000 Virginians died of disease or were killed in the Indian massacre of 1622.[10] | ||

George Yeardley took over as Governor of Virginia in 1619. He ended one-man rule and created a representative system of government with the General Assembly, the first elected legislative assembly in the New World.

Also in 1619, the Virginia Company sent 90 single women as potential wives for the male colonists to help populate the settlement. That same year the colony acquired a group of "twenty and odd" Angolans, brought by two English privateers. They were probably the first Africans in the colony. They, along with many European indentured servants helped to expand the growing tobacco industry which was already the colony's primary product. Although these black men were treated as indentured servants, this marked the beginning of America's history of slavery. Major importation of African slaves by both African and Europeans profiteers did not take place until much later in the century.

Also in 1619, the plantations and developments were divided into four "incorporations" or "citties" (sic), as they were called. These were Charles Cittie, Elizabeth Cittie, Henrico Cittie, and James Cittie, which included the relatively small seat of government for the colony at Jamestown Island. Each of the four "citties" (sic) extended across the James River, the main conduit of transportation of the era. Elizabeth Cittie, know initially as Kecoughtan (a Native word with many variations in spelling by the English), also included the areas now known as South Hampton Roads and the Eastern Shore.

In some areas, individual rather than communal land ownership or leaseholds were established, providing families with motivation to increase production, improve standards of living, and gain wealth. Perhaps nowhere was this more progressive at than Sir Thomas Dale's ill-fated Henricus, a westerly-lying development located along the south bank of the James River, where natives were also to be provided an education at the Colony's first college.

About 6 miles (9.7 km) south of the falls at present-day Richmond, in Henrico Cittie the Falling Creek Ironworks was established near the confluence of Falling Creek, using local ore deposits to make iron. It was the first in North America.

Virginians were intensely individualistic at this point, weakening the small new communities. According to Breen (1979) their horizon was limited by the present or near future. They believed that the environment could and should be forced to yield quick financial returns. Thus everyone was looking out for number one at the expense of the cooperative ventures. Farms were scattered and few villages or towns were formed. This extreme individualism led to the failure of the settlers to provide defense for themselves against the Indians, resulting in two massacres.[11]

Conflict with natives

While the developments of 1619 and continued growth in the several following years were seen as favorable by the English, many aspects, especially the continued need for more land to grow tobacco, were the source of increasing concern to the Native Americans most affected, the Powhatan.

The central issue was who would be in charge. The Powhatan formally and ritually admitted Virginia into their political system in 1607 and 1608. For years under the rule of Chief Powhatan, and even later, they fought to enforce the control they felt was rightfully theirs. The colonists, however, never recognized Powhatan's authority, and they also fought to take control.

By this time, the remaining Powhatan Empire was led by Chief Opechancanough, chief of the Pamunkey, and brother of Chief Powhatan. He had earned a reputation as a fierce warrior under his brother's chiefdom. Soon, he gave up on hopes of diplomacy, and resolved to eradicate the English colonists.

On March 22, 1622, the Powhatan killed about 400 colonists in the Indian Massacre of 1622. With coordinated attacks, they struck almost all the English settlements along the James River, on both shores, from Newport News Point on the east at Hampton Roads all the way west upriver to Falling Creek, a few miles above Henricus and John Rolfe's plantation, Varina Farms.[12]

At Jamestown, a warning by an Indian boy named Chanco to his employer, Richard Pace, helped reduce total deaths. Pace secured his plantation, and rowed across the river during the night to alert Jamestown, which allowed colonists some defensive preparation. They had no time to warn outposts, which suffered deaths and captives at almost every location. Several entire communities were essentially wiped out, including Henricus and Wolstenholme Towne at Martin's Hundred. At the Falling Creek Ironworks, which had been seen as promising for the Colony, two women and three children were among the 27 killed, leaving only two colonists alive. The facilities were destroyed.

Despite the losses, two thirds of the colonists survived; after withdrawing to Jamestown, many returned to the outlying plantations, although some were abandoned. The English carried out reprisals against the Powhatan and there were skirmishes and attacks for about a year before the colonists and Powhatan struck a truce.

The colonists invited the chiefs and warriors to Jamestown, where they proposed a toast of liquor. Dr. John Potts and some of the Jamestown leadership had poisoned the natives' share of the liquor, which killed about 200 men. Colonists killed another 50 Indians by hand.

The period between the coup of 1622 and another Powhatan attack on English colonists along the James River (see Jamestown) in 1644 marked a turning point in the relations between the Powhatan and the English In the early period, each side believed it was operating from a position of power; by 1646, the colonists had taken the balance of power.

The colonists defined the 1644 coup as an "uprising". Chief Opechancanough expected the outcome would reflect what he considered the morally correct position: that the colonists were violating their pledges to the Powhatan. During the 1644 event, Chief Opechancanough was captured. While imprisoned, he was murdered by one of his guards. After the death of Opechancanough, and following the repeated colonial attacks in 1644 and 1645, the remaining Powhatan tribes had little alternative but to accede to the demands of the settlers.[13]

Royal colony

In 1624, the Virginia Company's charter was revoked and the colony transferred to royal authority as a crown colony, but the elected representatives in Jamestown continued to exercise a fair amount of power. Under royal authority, the colony began to expand to the North and West with additional settlements. In 1630, under the governorship of John Harvey, the first settlement on the York River was founded. In 1632, the Virginia legislature voted to build a fort to link Jamestown and the York River settlement of Chiskiack and protect the colony from Indian attacks. This fort would become Middle Plantation and later Williamsburg, Virginia. In 1634, a palisade was built near Middle Plantation. This wall stretched across the peninsula between the York and James rivers and protected the settlements on the eastern side of the lower Peninsula from Indians. The wall also served to contain cattle.

Also in 1634, a new system of local government was created in the Virginia Colony by order of the King of England. Eight shires were designated, each with its own local officers. These shires were renamed as counties only a few years later. They were:

- Accomac (now Northampton County)

- Charles City Shire (now Charles City County)

- Charles River Shire (now York County)

- Elizabeth City Shire (existed as Elizabeth City County until 1952, when it was absorbed into the city of Hampton)

- Henrico (now Henrico County)

- James City Shire (now James City County)

- Warwick River Shire (existed as Warwick County until 1952, then the city of Warwick until 1958 when it was absorbed into the city of Newport News)

- Warrosquyoake Shire (now Isle of Wight County)

Of these, as of 2011, five of the eight original shires of Virginia are considered still extant in essentially their same political form (county), although some boundaries have changed. Also, including the earlier names of the cities (sic) in their names resulted in the source of some confusion, as that resulted in such seemingly contradictory names as "James City County" and "Charles City County".

Governor Berkeley

The first significant attempts at exploring the Trans-Allegheny region occurred under the administration of Governor William Berkeley. Efforts to explore farther into Virginia were hampered in 1644 when about 500 colonists were killed in another Indian massacre led, once again, by Opechancanough. Berkeley is credited with efforts to develop others sources of income for the colony besides tobacco such as cultivation of mulberry trees for silkworms and other crops at his large Green Spring Plantation, now a largely unexplored archaeological site maintained by the National Park Service near Jamestown and Williamsburg.

Most Virginia colonists were loyal to the crown (Charles I) during the English Civil War, but in 1652, Oliver Cromwell sent a force to remove and replace Gov. Berkeley with Governor Richard Bennett, who was loyal to the Commonwealth of England. This governor was a moderate Puritan who allowed the local legislature to exercise most controlling authority, and spent much of his time directing affairs in neighboring Maryland Colony. Bennett was followed by two more "Cromwellian" governors, Edward Digges and Samuel Matthews, although in fact all three of these men were not technically appointees, but were selected by the House of Burgesses, which was really in control of the colony during these years.[14]

Many royalists fled to Virginia after their defeat in the English Civil War. Many of them established what would become the most important families in Virginia. After the Restoration, in recognition of Virginia's loyalty to the crown, King Charles II of England bestowed Virginia with the nickname "The Old Dominion", which it still bears today.

Bacon's Rebellion

Governor Berkeley, who remained popular after his first administration, returned to the governorship at the end of Commonwealth rule. However, Berkeley's second administration was characterized with many problems. Disease, hurricanes, Indian hostilities, and economic difficulties all plagued Virginia at this time. Berkeley established autocratic authority over the colony. To protect this power, he refused to have new legislative elections for 14 years in order to protect a House of Burgesses that supported him. He only agreed to new elections when rebellion became a serious threat.

Berkeley finally did face a rebellion in 1676. Indians had begun attacking encroaching settlers as they expanded to the north and west. Serious fighting broke out when settlers responded to violence with a counter-attack against the wrong tribe, which further extended the violence. Berkeley did not assist the settlers in their fight. Many settlers and historians believe Berkeley's refusal to fight the Indians stemmed from his investments in the fur trade. Large scale fighting would have cut off the Indian suppliers Berkeley's investment relied on. Nathaniel Bacon organized his own militia of settlers who retaliated against the Indians. Bacon became very popular as the primary opponent of Berkeley, not only on the issue of Indians, but on other issues as well. Berkeley condemned Bacon as a rebel, but pardoned him after Bacon won a seat in the House of Burgesses and accepted it peacefully. After a lack of reform, Bacon rebelled outright, captured Jamestown, and took control of the colony for several months. The incident became known as Bacon's Rebellion. Berkeley returned himself to power with the help of the English militia. Bacon burned Jamestown before abandoning it and continued his rebellion, but died of disease. Berkeley severely crushed the remaining rebels.

In response to Berkeley's harsh repression of the rebels, the English government removed him from office. After the burning of Jamestown, the capital was temporarily moved to Middle Plantation, located on the high ground of the Virginia Peninsula equidistant from the James and York Rivers.[15]

College of William and Mary; capital relocated

Local leaders had long desired a school of higher education, for the sons of planters, and for educating the Indians. An earlier attempt to establish a permanent university at Henricus failed after the Indian Massacre of 1622 wiped out the entire settlement. Finally, seven decades later, with encouragement from the Colony's House of Burgesses and other prominent individuals, Reverend Dr. James Blair, the colony's top religious leader, prepared a plan. Blair went to England and in 1693, obtained a charter from King William and Queen Mary II of England. The college was named the College of William and Mary in honor of the two monarchs.

The rebuilt statehouse in Jamestown burned again in 1698. After that fire, upon suggestion of college students, the colonial capital was permanently moved to nearby Middle Plantation again, and the town was renamed Williamsburg, in honor of the king. Plans were made to construct a capitol building and plat the new city according to the survey of Theodorick Bland.

Governor Spotswood

Alexander Spotswood became lieutenant governor, or acting royal governor, of Virginia 1710, a post he held until recalled in 1722.

In 1716 he led an expedition of westward exploration, later known as the Knights of the Golden Horseshoe Expedition. Spotswood's party reached the top ridge of the Blue Ridge Mountains at Swift Run Gap (elevation 2,365 feet (721 m)). Such was the English colonials understanding of the extent of the land, that they thought they had reached the continental divide. There was some expectation that, "like Balboa", they would be overlooking the Pacific Ocean.[16] Spotswood was also behind the creation of Germanna, a settlement of German immigrants brought over for the purpose of iron production, in modern-day Spotsylvania County, itself named after Spotswood.

Social order

Historian Edmund Morgan (1975) argues that Virginians in the 1650s—and for the next two centuries—turned to slavery and a racial divide as an alternative to class conflict. "Racism made it possible for white Virginians to develop a devotion to the equality that English republicans had declared to be the soul of liberty." That is, white men became politically much more equal than was possible without a population of low-status slaves.[17]

By 1700 the population reached 70,000 and continued to grow rapidly from a high birth rate, low death rate, importation of slaves from the Caribbean, and immigration from Britain and Germany, as well as from Pennsylvania. The climate was mild, the farm lands were cheap and fertile.[18]

Historian Douglas Southall Freeman has explained the hierarchical social structure of the 1740s:

West of the fall line... the settlements fringed toward the frontier of the Blue Ridge and the Valley of the Shenandoah. Democracy was real where life was raw. In Tidewater, the flat country East of the fall line, there were no less than eight strata of society. The uppermost and the lowliest, the great proprietors and the Negro slaves, were supposed to be of immutable station. The others were small farmers, merchants, sailors, frontier folk, servants and convicts. Each of these constituted a distinct class at a given time, but individuals and families often shifted materially in station during a single generation. Titles hedged the ranks of the notables. Members of the Council of State were termed both "Colonel" and "Esquire." Large planters who did not bear arms almost always were given the courtesy title of "Gentlemen." So were Church Wardens, Vestrymen, Sheriffs and Trustees of towns. The full honors of a man of station were those of Vestryman [of the Church], Justice [lifetime member of the County Court, appointed by the legislature] and Burgess [elected member of the legislature]. Such an individual normally looked to England and especially to London and sought to live by the social standards of the mother country.[19]

Religion in early Virginia

- Further information: Episcopal Diocese of Virginia:History

The Church of England was legally established in the colony in 1619, and authorities in England sent in 22 Anglican clergyman by 1624. In practice, establishment meant that local taxes were funneled through the local parish to handle the needs of local government, such as roads and poor relief, in addition to the salary of the minister. There never was a bishop in colonial Virginia, and in practice the local vestry consisted of laymen controlled the parish.[20]

Anglican parishes

After five very difficult years, during which the majority of the new arrivals quickly died, the colony began to grow more successfully. As in England, the parish became a unit of local importance, equal in power and practical aspects to other entities, such as the courts and even the House of Burgesses and the Governor's Council (the precursors of the Virginia General Assembly). (A parish was normally led spiritually by a rector and governed by a committee of members generally respected in the community which was known as the vestry). A typical parish contained three or four churches, as the parish churches needed to be close enough for people to travel to worship services, where attendance was expected of everyone. Parishes typically had a church farm (or "glebe") to help support it financially.[21]

Expansion and subdivision of the church parishes and, after 1634, the shires (or counties) followed population growth. The intention of the Virginia parish system was to place a church not more than six miles (10 km)-easy riding distance-from every home in the colony. The shires, soon after initial establishment in 1634 known as "counties", were planned to be not more than a day's ride from all residents, so that court and other business could be attended to in a practical manner.

In the 1740s, the established Anglican church had about 70 parish priests around the colony. There was no bishop, and indeed, there was fierce political opposition to having a bishop in the colony. The Anglican priests were supervised directly by the Bishop of London. Each county court gave tax money to the local vestry, composed of prominent layman. The vestry provided the priest a glebe of 200 or 300 acres (1.2 km2), a house, and perhaps some livestock. The vestry paid him an annual salary of 16,000 pounds-of-tobacco, plus 20 shillings for every wedding and funeral. While not poor, the priests lived modestly and their opportunities for improvement were slim.

Missionaries

Religious leaders in England felt they had a duty as missionaries to bring Christianity (or more specifically, the religious practices and beliefs of the Church of England), to the Native Americans. There was an assumption that their own "mistaken" spiritual beliefs were largely the result of a lack of education and literacy, since the Powhatan did not have a written language. Therefore, teaching them these skills would logically result in what the English saw as "enlightenment" in their religious practices, and bring them into the fold of the church, which was part of the government, and hence, a form of control.

The efforts to educate and convert the natives were minimal, though the Indian school remained open until the Revolution. Apart from the Nansemond tribe, which had converted in 1638, and a few isolated individuals over the years, the other Powhatan tribes as a whole did not fully convert to Christianity until 1791.[22]

Alternatives to the established church

The colonists were typically inattentive, disinterested, and bored during church services, according to the ministers, who complained that the people were sleeping, whispering, ogling the fashionably dressed women, walking about and coming and going, or at best looking out the windows or staring blankly into space.[23] The lack of towns means the church had to serve scattered settlements, while the acute shortage of trained ministers meant that piety was hard to practice outside the home. Some ministers solved their problems by encouraged parishioners to become devout at home, using the Book of Common Prayer for private prayer and devotion (rather than the Bible). This allowed devout Anglicans to lead an active and sincere religious life apart from the unsatisfactory formal church services. However the stress on private devotion weakened the need for a bishop or a large institutional church of the sort Blair wanted. The stress on personal piety opened the way for the First Great Awakening, which pulled people away from the established church.[24]

Especially in the back country, most families had no religious affiliation whatsoever and their low moral standards were shocking to proper Englishmen[25] The Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians and other evangelicals directly challenged these lax moral standards and refused to tolerate them in their ranks. The evangelicals identified as sinful the traditional standards of masculinity which revolved around gambling, drinking, and brawling, and arbitrary control over women, children, and slaves. The religious communities enforced new standards, creating a new male leadership role that followed Christian principles and became dominant in the 19th century.[26] Baptists, German Lutherans and Presbyterians, funded their own ministers, and favored disestablishment of the Anglican church.

Presbyterians

The Presbyterians were evangelical dissenters, mostly Scots-Irish Americans who expanded in Virginia between 1740 and 1758, immediately before the Baptists. Spangler (2008) argues they were more energetic and held frequent services better atuned to the frontier conditions of the colony. Presbyterianism grew in frontier areas where the Anglicans had made little impress, especially the western areas of the Piedmont and the valley of Virginia. Uneducated whites and blacks were attracted to the emotional worship of the denomination, its emphasis on biblical simplicity, and its psalm singing. Presbyterians were a cross-section of society; they were involved in slaveholding and in patriarchal ways of household management, while the Presbyterian Church government featured few democratic elements.[27] Some local Presbyterian churches, such as Briery in Prince Edward County owned slaves. The Briery church purchased five slaves in 1766 and raised money for church expenses by hiring them out to local planters.[28]

Baptists

Helped by the First Great Awakening and numerous itinerant self-proclaimed missionaries, by the 1760s Baptists were drawing Virginians, especially poor white farmers, into a new, much more democratic religion. Slaves were welcome at the services and many became Baptists at this time. Baptist services were highly emotional; the only ritual was baptism, which was applied by immersion (not sprinkling like the Anglicans) only to adults. Opposed to the low moral standards prevalent in the colony, the Baptists strictly enforced their own high standards of personal morality, with special concern for sexual misconduct, heavy drinking, frivolous spending, missing services, cursing, and revelry. Church trials were held frequently and members who did not submit to disciple were expelled.[29]

Historians have debated the implications of the religious rivalries for the American Revolution. The Baptist farmers did introduce a new egalitarian ethic that largely displaced the semi-aristocratic ethic of the Anglican planters. However, both groups supported the Revolution. There was a sharp contrast between the austerity of the plain-living Baptists and the opulence of the Anglican planters, who controlled local government. Baptist church discipline, mistaken by the gentry for radicalism, served to ameliorate disorder. As population became more dense, the county court and the Anglican Church were able to increase their authority. The Baptists protested vigorously; the resulting social disorder resulted chiefly from the ruling gentry's disregard of public need. The vitality of the religious opposition made the conflict between 'evangelical' and 'gentry' styles a bitter one.[30] The strength of the evangelical movement's organization determined its ability to mobilize power outside the conventional authority structure.[31] The struggle for religious toleration erupted and was played out during the American Revolution, as the Baptists, in alliance with Anglicans Thomas Jefferson and James Madison worked successfully to disestablish the Anglican church.[32]

Methodists

Methodist missionaries were also active in the late colonial period. From 1776 to 1815 Methodist Bishop Francis Asbury made 42 trips into the western parts to visit Methodist congregations. During the war about 700 Methodist slaves went over to the British, who freed them and in 1791 helped them resettle in Sierra Leone in Africa.[33] In the 1780s itinerant Methodist preachers carried copies of an anti-slavery petition in their saddlebags throughout the state, calling for an end to slavery. At the same time, counter-petitions were circulated. The petitions were presented to the Assembly; they were debated, but no legislative action was taken, and after 1800 there was less and less religious opposition to slavery.[34]

Religious freedom and disestablishment

The Baptists and Presbyterians were subject to many legal constraints and faced growing persecution; between 1768 and 1774 about half of the Baptists ministers in Virginia were jailed for preaching. At the start of the Revolution, however, the Anglican Patriots realized that they needed dissenter support for effective wartime mobilization, so they met most of the dissenters' demands for the freedom to practice their religion in return for their support of the war effort.[35]

After the victory at Yorktown, the Anglican establishment sought to reintroduce state support for religion. This effort failed when non-Anglicans gave their full support to Thomas Jefferson's Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom, which became law in 1786. With Freedom of religion the new watchword, the Church of England was dis-established in Virginia. Most ministers were Loyalists and returned to England. When possible, worship continued in the usual fashion, but the local vestry was no longer the recipient of tax money and no longer had local government functions such as poor relief. The Right Reverend James Madison (1749–1812), a cousin of Patriot James Madison, was appointed in 1790 as the first Episcopal Bishop of Virginia and slowly rebuilt the denomination[36]

American Revolution

Antecedents

Revolutionary sentiments first began appearing in Virginia shortly after the French and Indian War ended in 1763. The very same year, the British and Virginian governments clashed in the case of Parson's Cause. The Virginia legislature had passed the Two-Penny Act to stop clerical salaries from inflating. King George III vetoed the measure, and clergy sued for back salaries. Patrick Henry first came to prominence by arguing in the case against the veto, which he declared tyrannical.

The British government had accumulated a great deal of debt through spending on its wars. To help payoff this debt, Parliament passed the Sugar Act in 1764 and the Stamp Act in 1765. The General Assembly opposed the passage of the Sugar Act on the grounds of no taxation without representation. Patrick Henry opposed the Stamp Act in the Burgesses with a famous speech advising George III that "Caesar had his Brutus, Charles I his Cromwell..." and the king "may profit by their example." The legislature passed the "Virginia Resolves" opposing the tax. Governor Francis Fauquier responded by dismissing the Assembly.

Opposition continued after the resolves. The Northampton County court overturned the Stamp Act February 8, 1766. Various political groups, including the Sons of Liberty met and issued protests against the act. Most notably, Richard Bland published a pamphlet entitled An Enquiry into the Rights of Ike British Colonies. This document would set one of the basic political principles of the Revolution by stating that Virginia was a part of the British Empire, not the Kingdom of Great Britain, so it only owed allegiance to the Crown, not Parliament.

The Stamp Act was repealed, but additional taxation from the Revenue Act and the 1769 attempt to transport Bostonian rioters to London for trial incited more protest from Virginia. The Assembly met to consider resolutions condemning on the transport of the rioters, but Governor Botetourt, while sympathetic, dissolved the legislature. The Burgesses reconvened in Raleigh Tavern and made an agreement to ban British imports. Britain gave up the attempt to extradite the prisoners and lifted all taxes except the tax on tea in 1770.

In 1773, because of a renewed attempt to extradite Americans to Britain, Richard Henry Lee, Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, George Mason, and others created a committee of correspondence to deal with problems with Britain. Unlike other such committees of correspondence, this one was an official part of the legislature.

Following the closure of the port in Boston and several other offenses, the Burgesses approved June 1, 1774 as a day of "Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer" in a show of solidarity with Massachusetts. The Governor, Lord Dunmore, dismissed the legislature. The first Virginia Convention was held August 1–6 to respond to the growing crisis. The convention approved a boycott of British goods, expressed solidarity with Massachusetts, and elected delegates to the Continental Congress where Virginian Peyton Randolph was selected as president of the Congress.

War begins

On April 20, 1775, a day after the Battle of Lexington and Concord, Dunmore ordered royal marines to remove the gunpowder from the Williamsburg Magazine to a British ship. Patrick Henry led a group of Virginia militia from Hanover in response to Dunmore's order. Carter Braxton negotiated a resolution to the Gunpowder Incident by transferring royal funds as payment for the powder. The incident exacerbated Dunmore's declining popularity. He fled the Governor's Palace to the British ship Fowey at Yorktown. On November 7, Dunmore issued a proclamation declaring Virginia was in a state of rebellion and that any slave fighting for the British would be freed. By this time, George Washington had been appointed head of the American forces by the Continental Congress and Virginia was under the political leadership of a Committee of Safety formed by the Third Virginia Convention in the governor's absence.

On December 9, 1775, Virginia militia moved on the governor's forces at the Battle of Great Bridge. The British had held a fort that guarded the land route to Norfolk. The British feared the militia, who had no cannon for a siege, would receive reinforcements, so they abandoned the fort and attacked. The militia won the 30 minute battle. Dunmore responded by bombarding Norfolk with his ships on January 1, 1776.

Independence

The Fifth Virginia Convention met on May 6 and declared Virginia a free and independent state on May 15, 1776. The convention instructed its delegates to introduce a resolution for independence at the Continental Congress. Richard Henry Lee introduced the measure on June 7. While the Congress debated, the Virginia Convention adopted George Mason's Bill of Rights (June 12) and a constitution (June 29) which established an independent commonwealth. Congress approved Lee's proposal on July 2 and approved Jefferson's Declaration of Independence on July 4.

The constitution of the Fifth Virginia Convention created a system of government for the state that would last for 54 years. The constitution provided for a chief magistrate, a bicameral legislature with both the House of Delegates and the Senate. The legislature elected a governor each year (picking Patrick Henry to be the first) and a council of eight for executive functions. In October, the legislature appointed Jefferson, Edmund Pendleton, and George Wythe to adopt the existing body of Virginia law to the new constitution.

After the Battle of Great Bridge, little military conflict took place on Virginia soil for the first part of the American Revolutionary War. Nevertheless, Virginia sent forces to help in the fighting to the North and South, including Daniel Morgan and his company of marksmen who fought in early battles in the north. Charlottesville served as a prison camp for the Convention Army, Hessian and British soldiers captured at Saratoga. Virginia also sent forces to its frontier in the northwest, which then included much of the Ohio Country. George Rogers Clark led forces in this area and captured the fort at Kaskaskia and won the Battle of Vincennes, capturing the royal governor, Henry Hamilton. Clark maintained control of areas south of the Ohio River for most of the war, but was unable to make gains in the Indian-dominated territories north of the river.

War returns to Virginia

The British brought the war back to coastal Virginia in May, 1779 when Admiral George Collier landed troops at Hampton Roads and used Portsmouth (after destroying the naval yard) as a base of attack. The move was part of an attempted blockade of trade with the West Indies. The British abandoned the plan when reinforcements from General Henry Clinton failed to arrive to support Collier.

Fearing the vulnerability of Williamsburg, then-Governor Thomas Jefferson moved the capital farther inland to Richmond in 1780. That October, the British made another attempt at invading Virginia. British General Alexander Leslie entered the Chesapeake with 2,500 troops and used Portsmouth as a base; however, after the British defeat at the Battle of Kings Mountain, Leslie moved to join General Charles Cornwallis farther south. In December, Benedict Arnold, who had betrayed the Revolution and become a general for the British, attacked Richmond with 1,000 soldiers and burned part of the city before the Virginia Miltia drove his army out of the city. Arnold moved his base of operations to Portsmouth and was later joined by another 2,000 troops under General William Phillips. Phillips led an expedition that destroyed military and economic targets, against ineffectual militia resistance. The state's defenses, led by General Friedrich Wilhelm, Baron von Steuben, put up resistance in the April 1781 Battle of Blandford, but was forced to retreat.

George Washington sent the French General Lafayette to lead the defense of Virginia. Lafayette marched south to Petersburg, preventing Phillips from immediately taking the town. Cornwallis, frustrated in the Carolinas, moved up from North Carolina to join Phillips and Arnold, and began to pursue Lafayette's smaller force. Lafayette only had 3,200 troops to face Cornwallis's 7,200. The outnumbered Lafayette avoided direct confrontation and could do little more than annoy Cornwallis with a series of skirmishes. Lafayette retreated to Fredericksburg, met up with General Anthony Wayne, and then marched into the southwest. Cornwallis dispatched two smaller missions: 500 soldiers under Colonel John Graves Simcoe to take the arsenal at Point of Fork and 250 under Colonel Banastre Tarleton to march on Charlottesville and capture Gov. Jefferson and the legislature. The expedition to Point of Fork forced Steuben to retreat further while Tarleton's mission captured only seven legislators and some officers. Jack Jouett had ridden all night ride to warn Jefferson and the legislators of Tarleton's coming.[2] Cornwallis reunited his army in Elk Hill and marched to the Tidewater region. Lafayette, uniting with von Steuben, now had 5,000 troops and followed Cornwallis.

Under orders from General Clinton, Cornwallis moved down the Virginia Peninsula towards the Chesapeake Bay were Clinton planned to extract part of the army for a siege of New York City. Cornwallis passed through Williamsburg and near Jamestown. When Cornwallis appeared to be moving to cross the James River, Lafayette saw a chance to attack Cornwallis during the crossing, and sent 800 troops under General Wayne against what they believed to be Cornwallis' rear guard. Cornwallis had set a trap, and Wayne was very nearly caught by the much larger, 5,000 soldier, main body of Cornwallis' forces at the Battle of Green Spring on July 6, 1781. Wayne ordered a charge against Cornwallis in order to feign greater strength and stop the British advance. Casualties were light with the Americans losing 140 and the British 75, but the ploy allowed the Americans to escape.

Cornwallis moved his troops across the James to Portsmouth to await Clinton's orders. Clinton decided that a position on the peninsula must be held and that Yorktown would be a valuable naval base. Cornwallis received orders to move his troops to Yorktown and begin construction of fortifications and a naval yard. The Americans had initially expected Cornwallis to move either to New York or the Carolinas and started to make arrangements to move from Virginia. Once they discovered the fortifications at Yorktown, the Americans began to place themselves around the city. Gen. Washington saw the opportunity for a major victory. He moved a portion of his troops, along with Rochambeau's French troops, from New York to Virginia. The plan hinged on French reinforcements of 3,200 troops and a large naval force under the Admiral de Grasse. On September 5, Admiral de Grasse defeated a fleet of the Royal Navy at the Battle of the Virginia Capes. The defeat ensured French dominance of the waters around Yorktown, thereby preventing Cornwallis from receiving troops or supplies and removing the possibility of evacuation. Between October 6 and 17 the American forces laid siege to Yorktown. Outgunned and completely surrounded, Cornwallis decided to surrender. Papers for surrender were officially signed on October 19. As a result of the defeat, the king lost control of Parliament and the new British government offered peace in April 1782. The Treaty of Paris of 1783 officially ended the war.

Early Republic and antebellum periods

Victory in the Revolution brought peace and prosperity to the new state, as export markets in Europe reopened for its tobacco.

While the old local elites were content with the status quo, younger veterans of the war had developed a national identity. Led by George Washington and James Madison, Virginia played a major role in the Constitutional Convention of 1787 in Philadelphia, where Madison proposed the Virginia Plan, which would give representation in Congress according to population. Virginia was the most populous state, and it was allowed to count all of its white residents and 3/5 of the black slaves for its congressional representation and its electoral vote. (Most white men owned land and could vote, but no one else.) Ratification was bitterly contested; the pro-Constitution forces prevailed only after promising to add a Bill of Rights. The Virginia Ratifying Convention approved the Constitution by a vote of 89-79 on June 25, 1788, becoming the tenth state to enter the Union.[37] Madison played a central role in the new Congress, while Washington was the unanimous choice as first president. He was followed by the Virginia Dynasty, including Thomas Jefferson, Madison, and James Monroe, giving the state four of the first five presidents.

Slavery and freedmen in Antebellum Virginia

The Revolution meant change and sometimes political freedom for enslaved African Americans, too. Thousands of slaves from southern states escaped to British lines and freedom during the war. Thousands left with the British for resettlement in their colonies of Nova Scotia and Jamaica; others went to England; others disappeared into rural and frontier areas or the North.[38] Inspired by the Revolution and evangelical preachers, numerous slaveholders in the Chesapeake region wrote wills that manumitted some or all of their slaves. From 1,800 in 1782, the population of free blacks in Virginia increased to 13,000 in 1790, and to 30,570 in 1810, a percentage change from less than one percent of the population to 7.2 percent.[39][clarification needed] One planter, Robert Carter III freed more than 450 slaves in his lifetime, more than anyone else.[40]

Many free blacks migrated from rural areas to towns such as Petersburg, Richmond, and Charlottesville for jobs and community; others migrated with their families to the frontier where social strictures were more relaxed.[41][42] Among the oldest black Baptist congregations in the nation were two founded near Petersburg before the Revolution. Each moved into the city and built churches by the early 19th century.[43]

Twice Virginia experienced slave rebellions--Gabriel's Rebellion in 1800, and Nat Turner's Rebellion in 1831. White reaction was swift and harsh, and militias killed many innocent blacks as well as people involved in the rebellions. After the second rebellion, the legislature passed laws restricting the rights of free people of color.[clarification needed] It restricted their education as well.

Westward expansion

Beginning in the 1750s, the Ohio Company of Virginia was created to survey and settle its new lands. Following the French and Indian War, westward settlement by Virginians was limited to more southern portions of the American Old West. In 1784 Virginia relinquished its claims to the Northwest Territory, except for the Virginia Military District. It was given to veterans of the Revolutionary War. In 1792, three western counties formed Kentucky.

As the new nation of the United States of America experienced growing pains and began to speak of Manifest Destiny, Virginia, too, found its role in the young republic to be changing and challenging. Beginning with the Louisiana Purchase, many of the Virginians whose grandparents had created the Virginia Establishment began to expand westward. Famous Virginian-born Americans affected not only the destiny of the state of Virginia, but the rapidly developing American Old West. Virginians Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were influential in their famous expedition to explore the Missouri River and possible connections to the Pacific Ocean. Notable names such as Stephen F. Austin, Edwin Waller, Haden Harrison Edwards, and Dr. John Shackelford were famous Texan pioneers from Virginia. Even eventual Civil War general Robert E. Lee distinguished himself as a military leader in Texas during the 1846-1848 Mexican-American War.

As the western reaches of Virginia were developed in the first half of the 19th century, the vast differences in the agricultural basis, cultural, and transportation needs of the area became a major issue for the Virginia General Assembly. In the older, eastern portion, slavery contributed to the economy. While planters were moving away from labor-intensive tobacco to mixed crops, they still held numerous slaves and their leasing out or sales was also part of their economic prospect. Slavery had become an economic institution upon which planters depended. Watersheds on most of this area eventually drained to the Atlantic Ocean. In the western reaches, families farmed smaller homesteads, mostly without enslaved or hired labor. Settlers were expanding the exploitation of resources: mining of minerals and harvesting of timber. The land drained into the Ohio River Valley, and trade followed the rivers.

Representation in the state legislature was heavily skewed in favor of the more populous eastern areas and the historic planter elite. This was compounded by the partial allowance for slaves when counting population; as neither the slaves nor women had the vote, this gave more power to white men. The legislature's efforts to mediate the disparities ended without meaningful resolution, although the state held a constitutional convention on representation issues. Thus, at the outset of the American Civil War, Virginia was caught not only in national crisis, but in a long-standing controversy within its own boundaries. While other border states had similar regional differences, Virginia had a long history of east-west tensions which finally came to a head; it was the only state to divide into two separate states during the War.

Infrastructure and Industrial Revolution

After the Revolution, various infrastructure projects began to be developed, including the Dismal Swamp Canal, the James River and Kanawha Canal, and various turnpikes. Virginia was home to the first of all Federal infrastructure projects under the new Constitution, the Cape Henry Light of 1792, located at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. Following the War of 1812, several Federal national defense projects were undertaken in Virginia. Drydock Number One was constructed in Portsmouth in the 1827. Across the James River, Fort Monroe was built to defend Hampton Roads, completed in 1834.

In the 1830s, railroads began to be built in Virginia. In 1831, the Chesterfield Railroad began hauling coal from the mines in Midlothian to docks at Manchester (near Richmond), powered by gravity and draft animals. The first railroad in Virginia to be powered by locomotives was the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad, chartered in 1834, with the intent to connect with steamboat lines at Aquia Landing running to Washington, D.C.. Soon after, others (with equally descriptive names) followed: the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad and Louisa Railroad in 1836, the Richmond and Danville Railroad in 1847, the Orange and Alexandria Railroad in 1848, and the Richmond and York River Railroad. In 1849, the Virginia Board of Public Works established the Blue Ridge Railroad. Under Engineer Claudius Crozet, the railroad successfully crossed the Blue Ridge Mountains via the Blue Ridge Tunnel at Afton Mountain.

Iron industry

With extensive iron deposits, especially in the western counties, Virginia was a pioneer in the iron industry. The first ironworks in the new world was established at Falling Creek in 1619, though it was destroyed in 1622. There would eventually grow to be 80 ironworks, charcoal furnaces and forges with 7,000 hands at any one time, about 70 percent of them slaves. Ironmasters hired slaves from local slave owners because they were cheaper than white workers, easier to control, and could not switch to a better employer. But the work ethic was weak, because the wages went to the owner, not to the workers, who were forced to work hard, were poorly fed and clothed, and were separated from their families. Virginia's industry increasingly fell behind Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Ohio, which relied on free labor. Bradford (1959) recounts the many complaints about slave laborers and argues the over-reliance upon slaves contributed to the failure of the ironmasters to adopt improved methods of production for fear the slaves would sabotage them. Most of the blacks were unskilled manual laborers, although Lewis (1977) reports that some were in skilled positions.[45][46]

Civil War

Virginia began a convention about secession on February 13, 1861 after six states seceded to form the Confederate States of America on February 4. Unionist members blocked secession but, on April 15 Lincoln called for troops from all states still in the Union in response to the firing on Fort Sumter. That meant Federal troops crossing Virginia on the way south to subdue South Carolina. On April 17, 1861 the convention voted to secede. The Confederacy rewarded the state by moving the national capital from Montgomery, Alabama to Richmond in late May—a decision that exposed the Confederate capital to unrelenting attacks and made Virginia a continuous battleground. Virginians ratified the articles of secession on May 23.[47] The following day, the Union army moved into northern Virginia and captured Alexandria without a fight, and controlled it for the remainder of the war.

The first major battle of the Civil War occurred on July 21, 1861. Union forces attempted to take control of the railroad junction at Manassas, but the Confederate Army had moved its forces by train to meet the Union. The Confederates won the First Battle of Manassas (known as "Bull Run" in Northern naming convention). Both sides mobilized for war; the year went on without another major fight.

Men from all economic and social levels, both slaveholders and nonslaveholders, as well as former Unionists, enlisted in great numbers. The only areas that sent few or no men to fight for the Confederacy had few slaves, a high percentage of poor families, and a history of opposition to secession, were located on the border with the North, and were sometimes under Union control.[48]

Richmond and war industry

After Virginia joined in secession, the capital of the Confederate States of American was relocated from Montgomery, Alabama, to Richmond. The White House of the Confederacy, located a few blocks north of the State Capital, was home to the family of Confederate President Jefferson Davis. A major center of iron production during the civil war was located in Richmond at Tredegar Iron Works. Tredegar was run partially by slave labor, and it produced most of the artillery for the war, making Richmond an important point to defend.

Petersburg became a manufacturing center, as well as a city where free black artisans and craftsmen could make a living. In 1860 half its population was black and of that, one-third were free blacks, the largest such population in the state. Richmond and Petersburg were linked by railroad before the Civil War, and the latter was an important shipping point for goods. Saltville was a primary source of Confederate salt (critical for food preservation and thus feeding the military) during the war, leading to the two Battles of Saltville. The most industrialized area of Virginia,[citation needed] around Wheeling, stayed loyal to the Union.

West Virginia breaks away

The western counties could not tolerate the Confederacy. Breaking away, they first formed the Union state of Virginia (recognized by Washington); it is called the Restored government of Virginia. The Restored government did little except give its permission for Congress to form the new state of West Virginia in 1862.[49]

At the Richmond secession convention on April 17, 1861, the delegates from western counties were 17 in favor and 30 against secession.[50] From May to August 1861, a series of Unionist conventions met in Wheeling; the Second Wheeling Convention constituted itself as a legislative body called the Restored Government of Virginia. It declared Virginia was still in the Union but that the state offices were vacant and elected a new governor, Francis H. Pierpont; this body gained formal recognition by the Lincoln administration on July 4.[51] On August 20 the Wheeling body passed an ordinance for the creation; it was put to public vote on Oct. 24. The vote was in favor of a new state—West Virginia—which was distinct from the Pierpont government, which persisted until the end of the war.[52] Congress and Lincoln approved, and, after providing for gradual emancipation of slaves in the new state constitution, West Virginia became the 35th state on June 20, 1863.[53]

During the War, West Virginia contributed about 32,000 soldiers to the Union Army and about 10,000 to the Confederate cause. The government in Richmond did not recognize the new state, and Confederates did not vote there. Everyone realized the decision would be made on the battlefield, and the government in Richmond sent in Robert E. Lee. But Lee found little local support and was defeated by Union forces from Ohio. Union victories in 1861 drove the Confederate forces out of the Monongahela and Kanawha valleys, and throughout the remainder of the war the Union held the region west of the Alleghenies and controlled the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in the north. The new state was not subject to Reconstruction.[54]

Later War Years

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2011) |

For the remainder of the war, battles were fought across Virginia, including the Seven Days Battles, the Battle of Fredericksburg, the Battle of Chancellorsville, the Battle of Brandy Station, the Overland Campaign and the Battle of the Wilderness, culminating in the Siege of Petersburg. In April 1865, Richmond was burned by a retreating Confederate Army and was returned to Union control. The Confederate government fled southwest to Danville, with the Army of Northern Virginia following. Days later, the Army of Northern Virginia surrendered at Appomattox.

Reconstruction

Virginia had been devastated by the war, with the infrastructure (such as railroads) in ruins; many plantations burned out; and large numbers of refugees without jobs, food or supplies beyond rations provided by the Union Army, especially its Freedman's Bureau.[55]

There were three phases in Virginia's Reconstruction era: wartime, presidential, and congressional.[56] Immediately after the war President Andrew Johnson recognized the Pierpont government as legitimate; it restored local government; passed Black Codes that gave the Freedman a higher status than slaves but they were not citizens, could not vote, and had only limited rights. It ratified the 13th amendment to abolish slavery (which had already disappeared), and revoked the 1861 ordnance of secession. That was enough for Johnson who said Reconstruction was complete. It was not adequate for the Radical Republicans in Congress who refused to seat the newly elected state delegation; the Radicals wanted proof that slavery was really dead (and not to be revived as some kind of serfdom), and that Virginia had truly renounced Confederate nationalism. After winning large majorities in the 1866 election, the Radical Republicans took full charge. They closed down the state's civilian government and put Virginia (and nine other ex-Confederate states) under military rule. Virginia was administered as the "First Military District" in 1867-69 under General John Schofield Meanwhile the Freedmen became politically active by forming their own political organizations, holding conventions, and demanding universal male suffrage and equal treatment under the law, as well as demanding disfranchisement of ex-Confederates and the seizure of their plantations.[57]

In 1867 James Hunnicutt (1814–1880), a white editor and Scalawag (white Virginian) mobilized the black Republican vote with promises of confiscating the large plantations and turning them over to the Freedmen. The moderate Republicans, including led by former Whigs, businessmen and planters, while supportive of black suffrage, drew the line at confiscation. Hunnicutt's coalition took control of the Republican Party, and began to demand the permanent disfranchisement of all whites who had supported the Confederacy. The Virginia Republican party was now permanently split, and many moderates switched to the opposition "Conservatives". The Radicals won the 1867 election for delegates to a constitutional convention.[58]

The 1868 constitutional convention included 33 white Conservatives, and 72 Radicals (of whom 24 were Blacks, 23 Scalawag, and 21 Carpetbaggers [59] Called the "Underwood Constitution" after the presiding officer, the main accomplishment was to reform the tax system, and create, for the first time in Virginia, a system of public schools[60] After furious debates over disfranchising Confederates, the new Constitution made it impossible for an ex-Confederate to hold office, but he could vote.[61] General Schofield, under pressure from national Republicans to be more moderate, still controlled the state through the Army. He appointed a personal friend, Henry H. Wells as provisional governor. Wells was a Carpetbagger and a former Union general. Using the Freedman's Bureau, to control the black element in the Republican Party, Schofield and Wells fought and defeated Hunnicutt and the Scalawag Republicans and ruined Hunnicutt's newspaper financially by taking away state printing. The national government ordered elections in 1869 that included a vote on the new Underwood constitution, a separate one on its two disfranchisement clauses that would have permanently stripped the vote from most former rebels, and a separate vote for state officials. The Army enrolled the Freedmen (ex-slaves) as voters but would not allow some 20,000 prominent whites to vote or hold office. The Republicans nominated Wells for governor, as Hunnicutt and most Scalawags went over to the opposition.[62]

The leader of the moderate Republicans, calling themselves "True Republicans" was William Mahone (1826–1895), a railroad president and former Confederate general who formed a coalition of white Scalawag Republicans, some blacks, and the ex-Democrats who formed the Conservative Party. Mahone said it was time for a New Departure for Virginia: whites had to accept the results of the war, including civil rights and the vote for Freedmen. Mahone convinced the Conservative Party to drop its own candidate and endorse Mahone's candidate for governor Gilbert C. Walker, while Mahone's people would endorse Conservatives for the legislative races. Mahone's plan worked, as the voters in 1869 elected Walker and defeated as well the proposed disfranchisement of ex-Confederates.[63] When the new legislature ratified the 14th and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, Congress seated its delegation and Virginia Reconstruction came to an end in January 1870. The Radical Republicans, although in power 1867-69 during Army rule, were thus ousted in a fair, non-violent election.[64] Indeed, Virginia was thus the only southern state not to have a civilian Radical government. Nevertheless white Virginians generally came to share the bitterness so typical of the southern attitudes.[65]

Gilded Age

Railroad and industrial growth

In addition to those that were rebuilt, new railroads developed after the Civil War. In 1868, under railroad baron Collis P. Huntington, the Virginia Central Railroad was merged and transformed into the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad. In 1870, several railroads were merged to form the Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio Railroad, later renamed Norfolk & Western. In 1880, the towpath of the now-defunct James River & Kanawha canal was transformed into the Richmond and Allegheny Railroad, which within a decade would merge into the Chesapeake & Ohio. Others would include the Southern Railroad, the Seaboard Air Line, and the Atlantic Coast Line; still others would eventually reach into Virginia, including the Baltimore & Ohio and the Pennsylvania Railroad. The rebuilt Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad eventually was linked to Washington, D.C..

In the 1880s, the Pocahontas Coalfield opened up in far southwest Virginia, with others to follow, in turn providing more demand for railroads transportation. In 1909, the Virginian Railway opened, built for the express purpose of hauling coal from the mountains of West Virginia to the ports at Hampton Roads. The growth of railroads resulted in the creation of new towns and rapid growth of others, including Clifton Forge, Roanoke, Crewe and Victoria. The railroad boom was not without incident: the Wreck of the Old 97 occurred en route from Danville to North Carolina in 1903, later immortalized by a popular ballad.

With the invention of the cigarette rolling machine, and the great increase in smoking in the early twentieth century, cigarettes and other tobacco products became a major industry in Richmond and Petersburg. Tobacco magnates such as Lewis Ginter funded a number of public institutions.

Readjustment, public education, segregation