History of hospitals

The history of hospitals has stretched over 2500 years, starting with precursors in the Ascelpian temples in ancient Greece and then the military hospitals in ancient Rome, though no civilian hospital existed in the Roman empire until the Christian period.[1] Towards the end of the 4th century, the "second medical revolution"[2] took place with the founding of the first Christian hospital in the eastern Byzantine Empire by Basil of Caesarea, and within a few decades, such hospitals had become ubiquitous in Byzantine society.[3] The hospital would undergo development and progress throughout Byzantine, medieval European and Islamic societies, until the early modern era where care and healing would transition into a secular affair.[4]

Antiquity

In ancient cultures, religion and medicine were linked. The earliest documented institutions aiming to provide cures were ancient Egyptian temples.

Greece

In ancient Greece, temples dedicated to the healer-god Asclepius, known as Asclepieia (Template:Lang-grc, sing. Asclepieion, Ἀσκληπιεῖον), functioned as centres of medical advice, prognosis, and healing.[5] Asclepeia provided carefully controlled spaces conducive to healing and fulfilled several of the requirements of institutions created for healing.[6] Under his Roman name Æsculapius, he was provided with a temple (291 B.C.) on an island in the Tiber in Rome, where similar rites were performed.[7]

At these shrines, patients would enter a dream-like state of induced sleep known as enkoimesis (ἐγκοίμησις) not unlike anesthesia, in which they either received guidance from the deity in a dream or were cured by surgery.[8] Asclepeia provided carefully controlled spaces conducive to healing and fulfilled several of the requirements of institutions created for healing.[6] In the Asclepieion of Epidaurus, three large marble boards dated to 350 BC preserve the names, case histories, complaints, and cures of about 70 patients who came to the temple with a problem and shed it there. Some of the surgical cures listed, such as the opening of an abdominal abscess or the removal of traumatic foreign material, are realistic enough to have taken place, but with the patient in a state of enkoimesis induced with the help of soporific substances such as opium.[8] The worship of Asclepius was adopted by the Romans.

India

Institutions created specifically to care for the ill also appeared early in India. Fa Xian, a Chinese Buddhist monk who travelled across India ca. 400 AD, recorded in his travelogue[9] that

The heads of the Vaishya [merchant] families in them [all the kingdoms of north India] establish in the cities houses for dispensing charity and medicine. All the poor and destitute in the country, orphans, widowers, and childless men, maimed people and cripples, and all who are diseased, go to those houses, and are provided with every kind of help, and doctors examine their diseases. They get the food and medicines which their cases require, and are made to feel at ease; and when they are better, they go away of themselves.

The earliest surviving encyclopaedia of medicine in Sanskrit is the Carakasamhita (Compendium of Caraka). This text, which describes the building of a hospital is dated by the medical historian Dominik Wujastyk to the period between 100 BCE and 150 CE.[10] The description by Fa Xian is one of the earliest accounts of a civic hospital system anywhere in the world and this evidence, coupled with Caraka’s description of how a clinic should be built and equipped, suggests that India may have been the first part of the world to have evolved an organized cosmopolitan system of institutionally-based medical provision.[11]

King Ashoka is wrongly said by many secondary sources to have founded at hospitals in ca. 230 BCE[12]

Sri Lanka

According to the Mahavamsa, the ancient chronicle of Sinhalese royalty, written in the sixth century CE, King Pandukabhaya of Sri Lanka (reigned 437 BCE to 367 BCE) had lying-in-homes and hospitals (Sivikasotthi-Sala) built in various parts of the country. This is the earliest documentary evidence we have of institutions specifically dedicated to the care of the sick anywhere in the world.[13][14] Mihintale Hospital is the oldest in the world.[15] Ruins of ancient hospitals in Sri Lanka are still in existence in Mihintale, Anuradhapura, and Medirigiriya.[16]

Roman and Byzantine

The Romans constructed buildings called valetudinaria for the care of sick slaves, gladiators, and soldiers around 100 BCE, and many were identified by later archeology. While their existence is considered proven, there is some doubt as to whether they were as widespread as was once thought, as many were identified only according to the layout of building remains, and not by means of surviving records or finds of medical tools.[17]

The declaration of Christianity as an accepted religion in the Roman Empire drove an expansion of the provision of care. Following First Council of Nicaea in 325 CE construction of a hospital in every cathedral town was begun. Among the earliest were those built by the physician Saint Sampson in Constantinople and by Basil of Caesarea in modern-day Turkey towards the end of the 4th century. By the beginning of the 5th century, the hospital had already become ubiquitous throughout the Christian east in the Byzantine world,[3] this being a dramatic shift from the pre-Christian era of the Roman Empire where no civilian hospitals existed.[1] Called the "Basilias", the latter resembled a city and included housing for doctors and nurses and separate buildings for various classes of patients.[18] There was a separate section for lepers.[19] Some hospitals maintained libraries and training programs, and doctors compiled their medical and pharmacological studies in manuscripts. Thus in-patient medical care in the sense of what we today consider a hospital, was an invention driven by Christian mercy and Byzantine innovation.[20] Byzantine hospital staff included the Chief Physician (archiatroi), professional nurses (hypourgoi) and the orderlies (hyperetai). By the twelfth century, Constantinople had two well-organized hospitals, staffed by doctors who were both male and female. Facilities included systematic treatment procedures and specialized wards for various diseases.[21]

Persia

A hospital and medical training centre also existed at Gundeshapur. The city of Gundeshapur was founded in 271 CE by the Sassanid king Shapur I. It was one of the major cities in Khuzestan province of the Persian empire, in Iran. A large percentage of the population were Syriacs, most of whom were Christians. Under the rule of Khusraw I, refuge was granted to Greek Nestorian Christian philosophers including the scholars of the Persian School of Edessa (Urfa) (also called the Academy of Athens), a Christian theological and medical university. These scholars made their way to Gundeshapur in 529 following the closing of the academy by Emperor Justinian. They were engaged in medical sciences and initiated the first translation projects of medical texts.[22] The arrival of these medical practitioners from Edessa marks the beginning of the hospital and medical centre at Gundeshapur.[23] It included a medical school and hospital (bimaristan), a pharmacology laboratory, a translation house, a library and an observatory.[24] Indian doctors also contributed to the school at Gundeshapur, most notably the medical researcher Mankah. Later after Islamic invasion, the writings of Mankah and of the Indian doctor Susruta were translated into Arabic at Baghdad's House of Wisdom.[25]

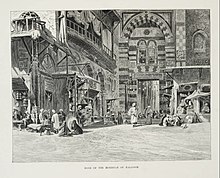

Medieval Islamic hospitals

The first Muslim hospital was an asylum to contain leprosy, built in the early eighth century, where patients were confined but, like the blind, were given a stipend to support their families.[26] The earliest general hospital was built in 805 in Baghdad by Harun Al-Rashid.[27][28] By the tenth century, Baghdad had five more hospitals, while Damascus had six hospitals by the 15th century and Córdoba alone had 50 major hospitals, many exclusively for the military.[26] Many of the prominent early Islamic hospitals were founded with assistance by Christians such as Jibrael ibn Bukhtishu from Gundeshapur.[29][30] "Bimaristan" is a compound of “bimar” (sick or ill) and “stan” (place). In the medieval Islamic world, the word "bimaristan" referred to a hospital establishment where the ill were welcomed, cared for and treated by qualified staff.

The United States National Library of Medicine credits the hospital as being a product of medieval Islamic civilization. Compared to contemporaneous Christian institutions, which were poor and sick relief facilities offered by some monasteries, the Islamic hospital was a more elaborate institution with a wider range of functions. In Islam, there was a moral imperative to treat the ill regardless of financial status. Islamic hospitals tended to be large, urban structures, and were largely secular institutions, many open to all, whether male or female, civilian or military, child or adult, rich or poor, Muslim or non-Muslim. The Islamic hospital served several purposes, as a center of medical treatment, a home for patients recovering from illness or accidents, an insane asylum, and a retirement home with basic maintenance needs for the aged and infirm.[31]

The typical hospital was divided into departments such as systemic diseases, surgery and orthopedics with larger hospitals having more diverse specialties. "Systemic diseases" was the rough equivalent of today's internal medicine and was further divided into sections such as fever, infections and digestive issues. Every department had an officer-in-charge, a presiding officer and a supervising specialist. The hospitals also had lecture theaters and libraries. Hospitals staff included sanitary inspectors, who regulated cleanliness, and accountants and other administrative staff.[26] The hospital in Baghdad employed twenty-five staff physicians.[32] The hospitals were typically run by a three-man board comprising a non-medical administrator, the chief pharmacist, called the shaykh saydalani, who was equal in rank to the chief physician, who served as mutwalli (dean).[33] Medical facilities traditionally closed each night, but by the 10th century laws were passed to keep hospitals open 24 hours a day.[34]

For less serious cases, physicians staffed outpatient clinics. Cities also had first aid centers staffed by physicians for emergencies that were often located in busy public places, such as big gatherings for Friday prayers to take care of casualties. The region also had mobile units staffed by doctors and pharmacists who were supposed to meet the need of remote communities. Baghdad was also known to have a separate hospital for convicts since the early 10th century after the vizier ‘Ali ibn Isa ibn Jarah ibn Thabit wrote to Baghdad’s chief medical officer that “prisons must have their own doctors who should examine them every day”. The first hospital built in Egypt, in Cairo's Southwestern quarter, was the first documented facility to care for mental illnesses while the first Islamic psychiatric hospital opened in Baghdad in 705.[35][26]

Medical students would accompany physicians and participate in patient care. Hospitals in this era were the first to require medical diplomas to license doctors.[36] The licensing test was administered by the region's government appointed chief medical officer. The test had two steps; the first was to write a treatise, on the subject the candidate wished to obtain a certificate, of original research or commentary of existing texts, which they were encouraged to scrutinize for errors. The second step was to answer questions in an interview with the chief medical officer. Physicians worked fixed hours and medical staff salaries were fixed by law. For regulating the quality of care and arbitrating cases, it is related that if a patient dies, their family presents the doctor's prescriptions to the chief physician who would judge if the death was natural or if it was by negligence, in which case the family would be entitled to compensation from the doctor. The hospitals had male and female quarters while some hospitals only saw men and other hospitals, staffed by women physicians, only saw women.[26] While women physicians practiced medicine, many largely focused on obstetrics.[37]

Hospitals were forbidden by law to turn away patients who were unable to pay.[34] Eventually, charitable foundations called waqfs were formed to support hospitals, as well as schools.[34] Part of the state budget also went towards maintaining hospitals.[26] While the services of the hospital were free for all citizens[34] and patients were sometimes given a small stipend to support recovery upon discharge, individual physicians occasionally charged fees.[26] In a notable endowment, a 13th-century governor of Egypt Al Mansur Qalawun ordained a foundation for the Qalawun hospital that would contain a mosque and a chapel, separate wards for different diseases, a library for doctors and a pharmacy[38] and the hospital is used today for ophthalmology.[26] The Qalawun hospital was based in a former Fatimid palace which had accommodation for 8,000 people -[39] "it served 4,000 patients daily."[40] The waqf stated,

"...The hospital shall keep all patients, men and women, until they are completely recovered. All costs are to be borne by the hospital whether the people come from afar or near, whether they are residents or foreigners, strong or weak, low or high, rich or poor, employed or unemployed, blind or sighted, physically or mentally ill, learned or illiterate. There are no conditions of consideration and payment, none is objected to or even indirectly hinted at for non-payment."[38]

The first, most well known physicians in the Medieval Islamic world were polymaths Ibn Sina, (Greek: Avicenna) and Al Rhazi (Greek: Rhazes) during the 10th and 11th centuries.[41]

Medieval Europe

Medieval hospitals in Europe followed a similar pattern to the Byzantine. They were religious communities, with care provided by monks and nuns. (An old French term for hospital is hôtel-Dieu, "hostel of God.") Some were attached to monasteries; others were independent and had their own endowments, usually of property, which provided income for their support. Some hospitals were multi-functional while others were founded for specific purposes such as leper hospitals, or as refuges for the poor, or for pilgrims: not all cared for the sick.

Around 529 A.D. St. Benedict of Nursia (480-543 A.D.), later a Christian saint, the founder of western monasticism and the Order of St. Benedict, today the patron saint of Europe, established the first monastery in Europe (Monte Cassino) on a hilltop between Rome and Naples, that became a model for the Western monasticism and one of the major cultural centers of Europe throughout the Middle Ages. St. Benedict wrote the Rule of Saint Benedict which mandated the moral obligations to care for the sick.

The first Spanish hospital, founded by the Catholic Visigoth bishop Masona in 580 CE at Mérida, was a xenodochium designed as an inn for travellers (mostly pilgrims to the shrine of Eulalia of Mérida) as well as a hospital for citizens and local farmers. The hospital's endowment consisted of farms to feed its patients and guests. From the account given by Paul the Deacon we learn that this hospital was supplied with physicians and nurses, whose mission included the care the sick wherever they were found, "slave or free, Christian or Jew."[42] In 650, the "Hôtel-Dieu" was found in Paris,[43] it is considered as the oldest worldwide hospital still operating today.[44] It was a multipurpose institution which catered for the sick and poor, offering shelter, food and medical care.

During the late 8th and early 9th centuries, Emperor Charlemagne decreed that those hospitals that had been well conducted before his time and had fallen into decay should be restored in accordance with the needs of the time.[45] He further ordered that a hospital should be attached to each cathedral and monastery.[45]

During the 10th century, the monasteries became a dominant factor in hospital work. The famous Benedictine Abbey of Cluny, founded in 910, set the example which was widely imitated throughout France and Germany. Besides its infirmary for the religious, each monastery had a hospital in which externs were cared for. These were in charge of the eleemosynarius, whose duties, carefully prescribed by the rule, included every sort of service that the visitor or patient could require.

As the eleemosynarius was obliged to seek out the sick and needy in the neighborhood, each monastery became a center for the relief of suffering. Among the monasteries notable in this respect were those of the Benedictines at Corbie in Picardy, Hirschau, Braunweiler, Deutz, Ilsenburg, Liesborn, Pram, and Fulda; those of the Cistercians at Arnsberg, Baumgarten, Eberbach, Himmenrode, Herrnalb, Volkenrode, and Walkenried.

No less efficient was the work done by the diocesan clergy in accordance with the disciplinary enactments of the councils of Aachen (817, 836), which prescribed that a hospital should be maintained in connection with each collegiate church. The canons were obliged to contribute towards the support of the hospital, and one of their number had charge of the inmates. As these hospitals were located in cities, more numerous demands were made upon them than upon those attached to the monasteries. In this movement the bishop naturally took the lead, hence the hospitals founded by Heribert (d. 1021) in Cologne, Godard (d. 1038) in Hildesheim, Conrad (d. 975) in Constance, and Ulrich (d. 973) in Augsburg. But similar provision was made by the other churches; thus at Trier the hospitals of Saint Maximin, Saint Matthew, Saint Simeon, and Saint James took their names from the churches to which they were attached. During the period 1207–1577 no less than one hundred and fifty-five hospitals were founded in Germany.[46]

The Ospedale Maggiore, traditionally named Ca' Granda (i.e. Big House), in Milan, northern Italy, was constructed to house one of the first community hospitals, the largest such undertaking of the fifteenth century. Commissioned by Francesco Sforza in 1456 and designed by Antonio Filarete it is among the first examples of Renaissance architecture in Lombardy.

The Normans brought their hospital system along when they conquered England in 1066. By merging with traditional land-tenure and customs, the new charitable houses became popular and were distinct from both English monasteries and French hospitals. They dispensed alms and some medicine, and were generously endowed by the nobility and gentry who counted on them for spiritual rewards after death.[47]

Late medieval Europe

The Hospitaller Order of St. John of Jerusalem, founded in 1099 (The Knights of Malta) itself has - as its raison d’être - the founding of a hospital for pilgrims to the Holy Land. In Europe, Spanish hospitals are particularly noteworthy examples of Christian virtue as expressed through care for the sick, and were usually attached to a monastery in a ward-chapel configuration, most often erected in the shape of a cross. This style reached a high point during the hospital building campaign of Portuguese St. John of God in the sixteenth-century, the founder of the Hospitaller Order of the Brothers of John of God.[48]

Soon many monasteries were founded throughout Europe, and everywhere there were hospitals like in Monte Cassino. By the 11th century, some monasteries were training their own physicians. Ideally, such physicians would uphold the Christianized ideal of the healer who offered mercy and charity towards all patients and soldiers, whatever their status and prognosis might be. In the 6th–12th centuries the Benedictines established lots of monk communities of this type. And later, in the 12th–13th centuries the Benedictines order built a network of independent hospitals, initially to provide general care to the sick and wounded and then for treatment of syphilis and isolation of patients with communicable disease. The hospital movement spread through Europe in the subsequent centuries, with a 225-bed hospital being built at York in 1287 and even larger facilities established at Florence, Paris, Milan, Siena, and other medieval big European cities.

In the North during the late Saxon period, monasteries, nunneries, and hospitals functioned mainly as a site of charity to the poor. After the Norman Conquest of 1066, hospitals are found to be autonomous, freestanding institutions. They dispensed alms and some medicine, and were generously endowed by the nobility and gentry who counted on them for spiritual rewards after death.[49] In time, hospitals became popular charitable houses that were distinct from both English monasteries and French hospitals.

The primary function of medieval hospitals was to worship to God. Most hospitals contained one chapel, at least one clergyman, and inmates that were expected to help with prayer. Worship was often a higher priority than care and was a large part of hospital life until and long after the Reformation. Worship in medieval hospitals served as a way of alleviating ailments of the sick and insuring their salvation when relief from sickness could not be achieved.[50][51]

The secondary function of medieval hospitals was charity to the poor, sick, and travellers. Charity provided by hospitals surfaced in different ways, including long-term maintenance of the infirm, medium-term care of the sick, short-term hospitality to travellers, and regular distribution of alms to the poor.[50]: 58 Though these were general acts of charity among medieval hospitals, the degree of charity was variable. For example, some institutions that perceived themselves mainly as a religious house or place of hospitality turned away the sick or dying in fear that difficult healthcare will distract from worship. Others, however, such as St. James of Northallerton, St. Giles of Norwich, and St. Leonard of York, contained specific ordinances stating they must cater to the sick and that "all who entered with ill health should be allowed to stay until they recovered or died".[50]: 58

The tertiary function of medieval hospitals was to support education and learning. Originally, hospitals educated chaplains and priestly brothers in literacy and history; however, by the 13th century, some hospitals became involved in the education of impoverished boys and young adults. Soon after, hospitals began to provide food and shelter for scholars within the hospital in return for helping with chapel worship.[50]: 65

Three well-documented medieval European hospitals are St. Giles in Norwich, St. Anthony's in London, and St. Leonards in York.[52] St. Giles, along with St. Anthony's and St. Leonards, were open ward hospitals that cared for the poor and sick in three of medieval England's largest cities.[52]: 23 The study of these three hospitals can provide insight into the diet, medical care, cleanliness and daily life in a medieval hospital of Europe.

St Giles, Norwich

Discrepancies exist among sources regarding the founding of St. Giles of Norwich, or the "Great Hospital" as it is known today. Some sources maintain that it was founded in 1246.[50]: 65 [51]: 140 [53] Other sources state that it was founded in 1249.[52]: 23 Though the date may be debatable, it seems agreed upon that The Great Hospital was founded by Walter Suffield, a Bishop known to be very liberal to the poor especially in the city of Norwich.[54] St Giles provided thirty beds and maintained within its ten-acre precinct, many meadows courtyards, ponds, and fruit trees until the late fifteenth century.[52]: 23, 34 The hospital cultivated many productive gardens abundant in apples, leeks, garlic, onions and honey. The gardens were so productive that surplus goods were sold on the open market. St Giles of Norwich owned six manors and advowson of eleven churches.[52]: 34

St Giles was unique in that food was provided for children who were getting free education elsewhere.[54]: 27 It is also noted that St Giles arranged for seven poor scholars to receive board at the hospital during their term at Norwich School.[50]: 65 Accommodations of early medieval hospitals were frequently communal. For example, in St Giles, the master and brothers ate in the common hall while sisters ate by themselves.[50]: 90 St Giles hospital was a complex building that housed a community of clergy with cloister and residential accommodation, a hospital and a parish church. St Giles was also wealthy enough to maintain its own kitchen and staff. This allowed poor men to receive a dish of meat, fish, eggs or cheese in addition to the customary daily ration of bread and drink.[50]: 122

St Anthony's, London

St Anthony's was erected in the thirteenth century (some time before 1254), in the heart of London on Threadneedle Street, atop the less than ideal site of a Jewish synagogue.[50]: 43, 88 [52]: 23 The chapel of St. Anthony's was built in 1310 without permission of the bishop of London. To prevents its degradation, the hospital petitioned for a chapel on the bishops terms.[50]: 88 Unlike St. Giles, there was insufficient land at St. Anthony's, London, for recreation or food production. As a result, herbs or 'erbys' and vegetables had to be bought on a daily basis for consumption by the entire community.[53]: 178 Accounts of foreign expenses at St. Anthony's also show the purchase of various spices, often with intrinsic medicinal qualities that could alter the level of heat and moisture within the body. Some of the spices bought include, saffron, cloves, ginger, cinnamon, lavender, pepper and mustard.[52]: 35 The amount spent on herbs, produce, and spices were far surpassed by the amount spent on fish and meat.

According to quarterly expenditure reports, fifty-eight percent of the quarterly budget was spent on meat, thirty-four percent on fish, three percent on pottage, two percent on dairy, one percent herbs and one percent on eggs.[52]: 33 The unusually detailed records of diet and expenditures at St. Anthony's have revealed that the diet of the clerical establishment ('the hall') and the diets of the almsmen, patients and children ('the hospital') were quite different and class-based.[53]: 179 During a typical week, "the entire community shared dishes of pottage, veal, mutton and eggs; the hall alone consumed pork, ribs of roast beef, duck, fresh salmon and eels; and the hospital was supplied with mutton, plaice and haddock."[52]: 41 It is clear that the hall, or more wealthy, enjoyed extravagant meals of meat and fish, while the hospital, the patients and the poor, were fed simpler and cheaper food.

In addition to its reputation of spending lavishly on food, St. Anthony's was famous for its grammar school, choir and pigs, which roamed freely among the streets identified by bells.[52]: 23 Pigs on sale in London, which were considered by officials to be unfit for food were handed over to St. Anthony's. The pigs were fed through charity or by scavenging and later, when their condition improved, they were then taken by the hospital for use as food for the poor or sick.[50]: 122

As mentioned, medieval hospitals became concerned in education and in the feeding and housing of students as early as the thirteenth century. In 1441, John Carpenter, the master of St. Anthony London, was able to finance a grammar school whose teachings were without fees to any student. This was the first source of free education in London and remained one of London's leading schools for one hundred years following its founding.[50]: 144

In 1449, St. Anthony's received a handsome legacy for the support of a clerk to train scholars in both polyphony and plainsong. St. Anthony's became so famous for its choir that in 1469, the royal minstrels set up a fraternity at the hospital so they may also study music.[53]: 125

St Leonards, York

St Leonard's was one on England's largest and richest hospitals with a primary purpose of caring for the poor, the sick, the old and infirm.[52]: 24 It maintained 200 beds and in its prosperous days, "maintained up to eighteen clergy, 16 sister and female servants, 30 choristers, 10 private boarders (corrodarians) and between 144 and 240 poor sick people."[50]: 36 Additionally, during Easter of 1370, records show accommodation of 224 sick and poor in the infirmary and 23 children in the orphanage.[54]: 156

The records of St Leonard provide the best details of daily hospital worship and patient life. In 1249, for example, matins and lauds were said in the morning hours of darkness, followed by mass of the Virgin Mary held by members of the clergy. The "lesser hours and mass of the day were said at mid-morning, vespers in the afternoon and compline in the early evening after supper."[50]: 50, 52 Sisters at St. Leonard's were instructed to feed the poor and the sick, wash them, and lead them around the grounds.[52]: 43 Although the food given to the sick were the simple, and often quite cheap, daily provisions, sisters were allowed to distribute special food if they were very ill.[50]: 62

At St Leonard's, charity and care for the sick was not only given to inmates of the hospitals, but also to the poor in other neighboring institutions as well as inmates of local leper houses.[50]: 63 Additionally, one or two of the chaplains at St Leonard's were instructed to "minister spiritually to the poor by speaking consoling words, hearing confessions, and administering the sacraments".[50]: 80

Early modern Europe

In Europe the medieval concept of Christian care evolved during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries into a secular one.[55] Theology was the problem. The Protestant reformers rejected the Catholic belief that rich men could gain God's grace through good works – and escape purgatory – by providing endowments to charitable institutions, and that the patients themselves could gain grace through their suffering.[56]

After the dissolution of the monasteries in 1540 by King Henry VIII the church abruptly ceased to be the supporter of hospitals, and only by direct petition from the citizens of London, were the hospitals St Bartholomew's, St Thomas's and St Mary of Bethlehem's (Bedlam) endowed directly by the crown; this was the first instance of secular support being provided for medical institutions.[57] It was at St. Bartholomew that William Harvey conducted his research on the circulatory system in the 17th century, Percivall Pott and John Abernethy developed important principles of modern surgery in the 18th century, and Mrs. Bedford Fenwich worked to advance the nursing profession in the late 19th century.[58]

There were 28 asylums in Sweden at the start of the Reformation. Gustav Vasa removed them from church control and expelled the monks and nuns, but allowed the asylums to keep their properties and to continue their activities under the auspices of local government.[59]

In much of Europe town governments operated small Holy Spirit hospitals, which had been founded in the 13th and 14th centuries. They distributed free food and clothing to the poor, provided for homeless women and children, and gave some medical and nursing care. Many were raided and closed during the Thirty Years War (1618–48), which ravaged the towns and villages of Germany and neighboring areas for three decades.

Meanwhile, in Catholic lands such as France, rich families continued to fund convents and monasteries that provided free health services to the poor. French practices were influenced by a charitable imperative which considered care of the poor and the sick to be a necessary part of Catholic practice. The nursing nuns had little faith in the power of physicians and their medicines alone to cure the sick; more important was providing psychological and physical comfort, nourishment, rest, cleanliness and especially prayer.[60]

In Protestant areas the emphasis was on scientific rather than religious aspects of patient care, and this helped develop a view of nursing as a profession rather than a vocation.[61] There was little hospital development by the main Protestant churches after 1530.[62] Some smaller groups such as the Moravians and the Pietists at Halle gave a role for hospitals, especially in missionary work.[63]

Enlightenment

In the 18th century, under the influence of the Age of Enlightenment, the modern hospital began to appear, serving only medical needs and staffed with trained physicians and surgeons. The nurses were untrained workers. The goal was to use modern methods to cure patients. They provided more narrow medical services, and were founded by the secular authorities. A clearer distinction emerged between medicine and poor relief. Within the hospitals, acute cases were increasingly treated alone, and separate departments were set up for different categories of patient.

The voluntary hospital movement began in the early 18th century, with hospitals being founded in London by the 1710s and 20s, including Westminster Hospital (1719) promoted by the private bank C. Hoare & Co and Guy's Hospital (1724) funded from the bequest of the wealthy merchant, Thomas Guy. Other hospitals sprang up in London and other British cities over the century, many paid for by private subscriptions. St. Bartholomew's in London was rebuilt in 1730, and the London Hospital opened in 1752.

These hospitals represented a turning point in the function of the institution; they began to evolve from being basic places of care for the sick to becoming centres of medical innovation and discovery and the principle place for the education and training of prospective practitioners. Some of the era's greatest surgeons and doctors worked and passed on their knowledge at the hospitals.[64] They also changed from being mere homes of refuge to being complex institutions for the provision of medicine and care for sick. The Charité was founded in Berlin in 1710 by King Frederick I of Prussia as a response to an outbreak of plague.

The concept of voluntary hospitals also spread to Colonial America; the Bellevue Hospital opened in 1736, Pennsylvania Hospital in 1752, New York Hospital in 1771, and Massachusetts General Hospital in 1811. When the Vienna General Hospital opened in 1784 (instantly becoming the world's largest hospital), physicians acquired a new facility that gradually developed into one of the most important research centres.[65]

Another Enlightenment era charitable innovation was the dispensary; these would issue the poor with medicines free of charge. The London Dispensary opened its doors in 1696 as the first such clinic in the British Empire. The idea was slow to catch on until the 1770s, when many such organizations began to appear, including the Public Dispensary of Edinburgh (1776), the Metropolitan Dispensary and Charitable Fund (1779) and the Finsbury Dispensary (1780). Dispensaries were also opened in New York 1771, Philadelphia 1786, and Boston 1796.[66]

Across Europe medical schools still relied primarily on lectures and readings. In the final year, students would have limited clinical experience by following the professor through the wards. Laboratory work was uncommon, and dissections were rarely done because of legal restrictions on cadavers. Most schools were small, and only Edinburgh, Scotland, with 11,000 alumni, produced large numbers of graduates.[67][68]

Spanish Americas

The first hospital founded in the Americas was the Hospital San Nicolás de Bari [Calle Hostos] in Santo Domingo, Distrito Nacional Dominican Republic. Fray Nicolás de Ovando, Spanish governor and colonial administrator from 1502–1509, authorized its construction on December 29, 1503. This hospital apparently incorporated a church. The first phase of its construction was completed in 1519, and it was rebuilt in 1552.[69] Abandoned in the mid-18th century, the hospital now lies in ruins near the Cathedral in Santo Domingo.

Conquistador Hernán Cortés founded the two earliest hospitals in North America: the Immaculate Conception Hospital and the Saint Lazarus Hospital. The oldest was the Immaculate Conception, now the Hospital de Jesús Nazareno in Mexico City, founded in 1524 to care for the poor.[69]

Modern hospitals

English physician Thomas Percival (1740–1804) wrote a comprehensive system of medical conduct, Medical Ethics; or, a Code of Institutes and Precepts, Adapted to the Professional Conduct of Physicians and Surgeons (1803) that set the standard for many textbooks.[70]

In the mid 19th century, hospitals and the medical profession became more professionalized, with a reorganization of hospital management along more bureaucratic and administrative lines. The Apothecaries Act 1815 made it compulsory for medical students to practice for at least half a year at a hospital as part of their training.[71] An example of this professionalization was the Charing Cross Hospital, set up in 1818 as the 'West London Infirmary and Dispensary' from funds provided by Dr. Benjamin Golding. By 1821 it was treating nearly 10,000 patients a year, and it was relocated to larger quarters near Charing Cross in the heart of London. Its Charing Cross Hospital Medical School opened in 1822. It expanded several times and 1866 added a professional nursing staff.[72]

Florence Nightingale pioneered the modern profession of nursing during the Crimean War when she set an example of compassion, commitment to patient care and diligent and thoughtful hospital administration. The first official nurses’ training programme, the Nightingale School for Nurses, was opened in 1860, with the mission of training nurses to work in hospitals, to work with the poor and to teach.[73]

Nightingale was instrumental in reforming the nature of the hospital, by improving sanitation standards and changing the image of the hospital from a place the sick would go to die, to an institution devoted to recuperation and healing. She also emphasized the importance of statistical measurement for determining the success rate of a given intervention and pushed for administrative reform at hospitals.[74]

During the middle of the 19th century, the Second Viennese Medical School emerged with the contributions of physicians such as Carl Freiherr von Rokitansky, Josef Škoda, Ferdinand Ritter von Hebra, and Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis. Basic medical science expanded and specialization advanced. Furthermore, the first dermatology, eye, as well as ear, nose, and throat clinics in the world were founded in Vienna.[75]

By the late 19th century, the modern hospital was beginning to take shape with a proliferation of a variety of public and private hospital systems. By the 1870s, hospitals had more than tripled their original average intake of 3,000 patients. In continental Europe the new hospitals generally were built and run from public funds. Nursing was professionalized in France by the turn of the 20th century. At that time, the country's 1,500 hospitals were operated by 15,000 nuns representing over 200 religious orders. Government policy after 1900 was to secularize public institutions, and diminish the role the Catholic Church. This political goal came in conflict with the need to maintain better quality of medical care in antiquated facilities. New government-operated nursing schools turned out nonreligous nurses who were slated for supervisory roles. During the First World War, an outpouring of patriotic volunteers brought large numbers of untrained middle-class women into the military hospitals. They left when the war ended but the long-term effect was to heighten the prestige of nursing. In 1922 the government issued a national diploma for nursing.[76]

In the U.S., the number of hospitals reached 4400 in 1910, when they provided 420,000 beds.[77] These were operated by city, state and federal agencies, by churches, by stand-alone non-profits, and by for-profit enterprises. All the major denominations built hospitals; the 541 Catholic ones (in 1915) were staffed primarily by unpaid nuns. The others sometimes had a small cadre of deaconesses as staff.[78] Non-profit hospitals were supplemented by large public hospitals in major cities and research hospitals often affiliated with a medical school. The largest public hospital system in America is the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation, which includes Bellevue Hospital, the oldest U.S. hospital, affiliated with New York University Medical School.[79]

The National Health Service, the principal provider of health care in Britain, was founded in 1948, and took control of nearly all the hospitals.[80]

Paris Medicine

At the turn of the 19th century, Paris medicine played a significant role in shaping clinical medicine. New emphasis on physically examining the body led to methods such as percussion, inspection, palpation, auscultation, and autopsy.[81] The situation in Paris was particularly unique due to the fact that there was a very large concentration of medical professionals in a very small setting allowing for a large flow of ideas and the spread of innovation.[81] One of the innovations to come out of the Paris hospital setting was Laennec's stethoscope. Weiner states that the widespread acceptance of the stethoscope would likely not have happened in any other setting, and the setting allowed for Laennec to pass on this technology to the eager medical community that had gathered there. This invention also brought even more attention to the Paris scene.[81]

Before the start of the 19th century, there were many problems existing within the French medical system. These problems were outlined by many seeking to reform hospitals including a contemporary surgeon Jacques Tenon in his book Memoirs on Paris Hospitals. Some of the problems Tenon drew attention to were the lack of space, the inability to separate patients based on the type of illness (including those that were contagious), and general sanitation problems.[82] Additionally, the secular revolution led to the nationalization of hospitals previously owned by the Catholic Church and led to a call for a hospital reform which actually pushed for the deinstitutionalization of medicine.[83] This contributed to the state of disarray Paris hospitals soon fell into which ultimately called for the establishment of a new hospital system outlined in the law of 1794. The law of 1794 played a significant part in revolutionizing Paris Medicine because it aimed to address some of the problems facing Paris Hospitals of the time.

First, the law of 1794 created three new schools in Paris, Montpellier, and Strasbour due to the lack of medical professionals available to treat a growing French army. It also gave physicians and surgeons equal status in the hospital environment, whereas previously physicians were regarded as intellectually superior.[83] This led to the integration of surgery into traditional medical education contributing to a new breed of doctors that focused on pathology, anatomy and diagnosis. The new focus on anatomy was further facilitated by this law because it ensured that medical students had enough bodies to dissect.[83] Additionally, pathological education was furthered by the increased use of autopsies to determine a patient's cause of death.[81] Lastly, the law of 1794 allocated funds for full-time salaried teachers in hospitals, as well as creating scholarships for medical students.[83] Overall, the law of 1794 contributed to the shift of medical teaching away from theory and towards practice and experience, all within a hospital setting. Hospitals became a center for learning and development of medical techniques, which was a departure from the previous notion of a hospital as an area that accepted people who needed help of any kind, ill or not.[84] This shift was consistent with much of the philosophy of the time, particularly the ideas of John Locke who preached that observation using ones senses was the best way to analyze and understand a phenomenon.[83] Foucalt, however, criticized this shift in his book The Birth of the Clinic, stating that this shift took attention away from the patient and objectified patients, ultimately resulting in a loss of the patient's narrative. He argued that from this point forward, in the eyes of doctors, patients lost their humanity and became more like objects for inspection and examination.[85]

The next advancement in Paris medicine came with the creation of an examination system, that after 1803, was required for the licensing of all medical professions creating a uniform and centralized system of licensing.[83] This law also created another class of health professionals, mostly for those living outside of cities, who did not have to go through the licensing pricess but instead went through a simpler and shorter training process.[83]

Another area influenced by Paris hospitals was the development of specialties. The structure of a Paris hospital allowed physicians more freedom to pursue interests as well as providing the necessary resources.[81] An example of a physician who used this flexibility to conduct research is Phillipe Pinel who conducted a four-year study on the hospitalization and treatment of mentally-ill women within the Salpêtriére hospital. This was the first study ever done of this magnitude by a physician, and the Pinel was the first to realize that patients dealing with similar illnesses could be group together, compared, and classified.[81]

Church-sponsored hospitals and nurses

Protestants

The Protestant churches reentered the health field in the 19th century, especially with the establishment of orders of women, called deaconesses who dedicated themselves to nursing services. This movement began in Germany in 1836 when Theodor Fliedner and his wife opened the first deaconess motherhouse in Kaiserswerth on the Rhine. It became a model, and within half a century there were over 5,000 deaconesses in Europe. The Church of England named its first deaconess in 1862. The North London Deaconess Institution trained deaconesses for other dioceses and some served overseas.[86]

William Passavant in 1849 brought the first four deaconesses to Pittsburgh, in the United States, after visiting Kaiserswerth. They worked at the Pittsburgh Infirmary (now Passavant Hospital).[87]

The American Methodists made medical services a priority from the 1850s. They began opening charitable institutions such as orphanages and old people's homes. In the 1880s, Methodists began opening hospitals in the United States, which served people of all religious beliefs. By 1895, 13 hospitals were in operation in major cities.[88]

Catholics

In Quebec, Catholics operated hospitals continuously from the 1640s; they attracted nuns from the provincial elite. Jeanne Mance (1606–73) founded Montreal's city's first hospital, the Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal, in 1645. In 1657 she recruited three sisters of the Religious Hospitallers of St. Joseph, and continued to direct operations of the hospital. The project, begun by the niece of Cardinal de Richelieu was granted a royal charter by King Louis XIII and staffed by a colonial physician, Robert Giffard de Moncel.[89] The General Hospital in Quebec City opened in 1692. They often handled malaria, dysentery, and respiratory sickness.[90]

In the 1840s–1880s era, Catholics in Philadelphia founded two hospitals, for the Irish and German Catholics. They depended on revenues from the paying sick, and became important health and welfare institutions in the Catholic community.[91] By 1900 the Catholics had set up hospitals in most major cities. In New York the Dominicans, Franciscans, Sisters of Charity, and other orders set up hospitals to care primarily for their own ethnic group. By the 1920s they were serving everyone in the neighborhood.[92] In smaller cities too the Catholics set up hospitals, such as St. Patrick Hospital in Missoula, Montana. The Sisters of Providence opened it in 1873. It was in part funded by the county contract to care for the poor, and also operated a day school and a boarding school. The nuns provided nursing care especially for infectious diseases and traumatic injuries among the young, heavily male clientele. They also proselytized the patients to attract converts and restore lapsed Catholics back into the Church. They built a larger hospital in 1890.[93] Catholic hospitals were largely staffed by Catholic orders of nuns, and nursing students, until the population of nuns dropped sharply after the 1960s. The Catholic Hospital Association formed in 1915.[94][95]

See also

References

- ^ a b Smith, Virginia. Clean: A History of Personal Hygiene and Purity. Oxford University Press, 2008, 142

- ^ (Albert Jonson. A Short History of Medical Ethics. Oxford University Press, 2000, 13.)

- ^ a b Nutton, Vivian. Ancient medicine. Routledge, 2012, 306-307

- ^ Cunningham, Andrew, and Ole Peter Grell, eds. Health care and poor relief in protestant Europe 1500-1700. Routledge, 2002, 130-133

- ^ Risse, G.B. Mending bodies, saving souls: a history of hospitals. Oxford University Press, 1990. p. 56 Books.Google.com

- ^ a b Risse, G.B. Mending bodies, saving souls: a history of hospitals. Oxford University Press, 1990. p. 56 Books.Google.com

- ^ Roderick E. McGrew, Encyclopaedia of Medical History (Macmillan 1985), pp.134–5.

- ^ a b Askitopoulou, H., Konsolaki, E., Ramoutsaki, I., Anastassaki, E. Surgical cures by sleep induction as the Asclepieion of Epidaurus. The history of anaesthesia: proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium, by José Carlos Diz, Avelino Franco, Douglas R. Bacon, J. Rupreht, Julián Alvarez. Elsevier Science B.V., International Congress Series 1242(2002), p.11-17. Books.Google.com

- ^ Legge, James, A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms: Being an Account by the Chinese Monk Fâ-Hien of his Travels in India and Ceylon (399–414 CE) in Search of the Buddhist Books of Discipline, 1965

- ^ https://www.academia.edu/1262042/_The_Nurses_should_be_able_to_Sing_and_Play_Instruments._The_Evidence_for_Early_Hospitals_in_South_Asia Cited on 2017-11-26.

- ^ Wujastyk, D (2003). The Roots of Ayurveda: selections from Sankskrit medical writings. London; New York: Penguin Books. pp. passim. ISBN 978-0140448245. OCLC 49872366.

- ^ Encyclopaedia of Medical History - McGrew, Roderick E. (Macmillan 1985), p. 135.

- ^ Prof. Arjuna Aluvihare, "Rohal Kramaya Lovata Dhayadha Kale Sri Lankikayo" Vidhusara Science Magazine, Nov. 1993.

- ^ Resource Mobilization in Sri Lanka's Health Sector - Rannan-Eliya, Ravi P. & De Mel, Nishan, Harvard School of Public Health & Health Policy Programme, Institute of Policy Studies, February 1997, p. 19. Accessed 2008-02-22.

- ^ Heinz E Müller-Dietz, Historia Hospitalium (1975).

- ^ Ayurveda Hospitals in ancient Sri Lanka Archived 7 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine – Siriweera, W. I., Summary of guest lecture, Sixth International Medical Congress, Peradeniya Medical School Alumni Association and the Faculty of Medicine

- ^ The Roman military Valetudinaria: fact or fiction – Baker, Patricia Anne, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, Sunday 20 December 1998

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia – [1] (2009)

- ^ Roderick E. McGrew, Encyclopedia of Medical History (1985), p. 135.

- ^ James Edward McClellan and Harold Dorn, Science and Technology in World History: An Introduction (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006), pp. 99, 101.

- ^ Byzantine medicine

- ^ Mahfuz Söylemez, Mehmet. "The Jundishapur School: Its History, Structure, and Functions". The American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences. 22 (2): 3.

- ^ Gail Marlow Taylor, The Physicians of Jundishapur, (University of California, Irvine), p. 7

- ^ Cyril Elgood, A Medical History of Persia and the Eastern Caliphate, (Cambridge University Press, 1951), p. 7

- ^ Cyril Elgood, A Medical History of Persia and the Eastern Caliphate, (Cambridge University Press, 1951), p. 3

- ^ a b c d e f g h "The Islamic Roots of the Modern Hospital". aramcoworld.com. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ^ Husain F. Nagamia, [Islamic Medicine History and Current practise], (2003), p.24.

- ^ Sir Glubb, John Bagot (1969), A Short History of the Arab Peoples, retrieved 2008-01-25

- ^ Guenter B. Risse, Mending Bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals, (Oxford University Press, 1999), p.125 [2]

- ^ The Hospital in Islam, [Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Islamic Science, An Illustrated Study], (World of Islam Festival Pub. Co., 1976), p.154.

- ^ Islamic Culture and the Medical Arts: Hospitals, United States National Library of Medicine

- ^ Husain F. Nagamia, Islamic Medicine History and Current Practice, (2003), p. 24.

- ^ "The Islamic roots of modern pharmacy". aramcoworld.com. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ a b c d Rise and spread of Islam. Gale. 2002. p. 419. ISBN 9780787645038.

- ^ Medicine And Health, "Rise and Spread of Islam 622–1500: Science, Technology, Health", World Eras, Thomson Gale.

- ^ Alatas, Syed Farid (2006). "From Jami'ah to University: Multiculturalism and Christian–Muslim Dialogue". Current Sociology. 54 (1): 112–32. doi:10.1177/0011392106058837.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "Pioneer Muslim Physicians". aramcoworld.com. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ^ a b Philip Adler; Randall Pouwels (2007). World Civilizations. Cengage Learning. p. 198. ISBN 9781111810566. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ Bedi N. Şehsuvaroǧlu (2012-04-24). "Bīmāristān". In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; et al. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ^ Mohammad Amin Rodini (7 July 2012). "Medical Care in Islamic Tradition During the Middle Ages" (PDF). International Journal of Medicine and Molecular Medicine. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ Cyril Elgood, A Medical History of Persia and the Eastern Caliphate, (Cambridge University Press, 1951), pp. 234–35. [3]

- ^ See Florez, "Espana Sagrada", XIII, 539; Heusinger, "Ein Beitrag", etc. in "Janus", 1846, I.

- ^ "Hotel Dieu". London Science Museum. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- ^ Radcliff, Walter (1989). Milestones in Midwifery and the Secret Instrument. Norman Publishing. ISBN 9780930405205.

- ^ a b Capitulary Duplex, 803, chapter iii

- ^ Virchow in "Gesch. Abhandl.", II

- ^ Watson, Sethina (2006). "The Origins of the English Hospital". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. Sixth Series. 16: 75–94. doi:10.1017/s0080440106000466. JSTOR 25593861.

- ^ Gordon, Benjamin, Medieval and Renaissance Medicine, (New York: Philosophical Library, 1959) , 313. Catholic Encyclopedia, ed. Charles Herberman, et al., Vol. VII, “Hospitals”, (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910), 481-2. By 1715, 150 years after the death of St. John of God, over 250 hospitals had been constructed throughout Europe and the New World through the assistance of the Order he founded. See Grace Goldin, Work of Mercy (Ontario: Boston Mills Press, 1994), 33, 50-57.

- ^ Watson Sethina (2006). "The Origins of the English Hospital". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. Sixth Series. 16: 75–94. doi:10.1017/s0080440106000466. JSTOR 25593861.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Orme, Nicholas; Webster, Margaret (1995). The English Hospital. Yale University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-300-06058-4.

- ^ a b Bowers, Barbara S. (2007). The Medieval Hospital and Medical Practice. Ashgate Publishing Limited. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-7546-5110-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Abreu, Laurinda (2013). Hospital Life : Theory and Practice from the Medieval to the Modern. Pieterlen Peter Lang International Academic Publishers. pp. 21–34. ISBN 978-3-0353-0517-3.

- ^ a b c d Rawcliffe, Carole (1999). Medicine for the Soul: The Life, Death and Resurrection of an English Medieval Hospital- St. Giles's Norwich, c. 1249–1550. Sutton Publishing. p. xvi. ISBN 978-0-7509-2009-4.

- ^ a b c Clay, Rotha Mary (1909). The Medieval Hospitals of England. London: Methuen & Co. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-7905-4209-6.

- ^ Andrew Cunningham; Ole Peter Grell (2002). Health Care and Poor Relief in Protestant Europe 1500–1700. Routledge. pp. 130–33. ISBN 9780203431344.

- ^ C. Scott Dixon; et al. (2009). Living With Religious Diversity in Early-Modern Europe. Ashgate. pp. 128–30. ISBN 9780754666684.

- ^ Keir Waddington (2003). Medical Education at St. Bartholomew's Hospital, 1123–1995. Boydell & Brewer. p. 18. ISBN 9780851159195.

- ^ Robinson, James O. (1993). "The Royal and Ancient Hospital of St Bartholomew (Founded 1123)". Journal of Medical Biography. 1 (1): 23–30. doi:10.1177/096777209300100105.

- ^ Virpi Mäkinen (2006). Lutheran Reformation And the Law. BRILL. pp. 227–29. ISBN 9789004149045.

- ^ Olwen Hufton, The Prospect before Her. A History of Women in Western Europe, 1500–1800 (1995), pp 382–84.

- ^ Tim McHugh, "Expanding Women’s Rural Medical Work in Early Modern Brittany: The Daughters of the Holy Spirit," Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences (2012) 67#3 pp 428-456. in project MJUSE

- ^ Johann Jakob Herzog; Philip Schaff (1911). The new Schaff-Herzog encyclopedia of religious knowledge. Funk and Wagnalls. pp. 468–9.

- ^ Christopher M. Clark (2006). Iron Kingdom: The Rise And Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947. Harvard U.P. p. 128. ISBN 9780674023857.

- ^ Reinarz, Jonathan (2007). "Corpus Curricula: Medical Education and the Voluntary Hospital Movement". Brain, Mind and Medicine: Essays in Eighteenth-Century Neuroscience. pp. 43–52. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-70967-3_4. ISBN 978-0-387-70966-6.

- ^ Roderick E. McGrew, Encyclopedia of Medical History (Macmillan 1985), p. 139.

- ^ Michael Marks Davis; Andrew Robert Warner (1918). Dispensaries, Their Management and Development: A Book for Administrators, Public Health Workers, and All Interested in Better Medical Service for the People. MacMillan. pp. 2–3.

- ^ Thomas H. Broman, "The Medical Sciences," in Roy Porter, ed, The Cambridge History of Science: Volume 4: 18th-century Science (2003) pp. 465–68

- ^ Lisa Rosner, Medical Education in the Age of Improvement: Edinburgh Students and Apprentices 1760–1826 (1991)

- ^ a b Alfredo De Micheli, En torno a la evolución de los hospitales, Gaceta Médica de México, vol. 141, no. 1 (2005), p. 59.

- ^ Waddington, Ivan (1975). "The Development of Medical Ethics – A Sociological Analysis". Medical History. 19 (1): 36–51. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.284.7913. doi:10.1017/s002572730001992x.

- ^ Porter, Roy (1999) [1997]. The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 316–17. ISBN 978-0-393-31980-4.

- ^ R.J. Minney, The Two Pillars Of Charing Cross: The Story of a Famous Hospital (1967)

- ^ Kathy Neeb (2006). Fundamentals of Mental Health Nursing. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company. ISBN 9780803620346.

- ^ Nightingale, Florence (August 1999). Florence Nightingale: Measuring Hospital Care Outcomes. ISBN 978-0-86688-559-1. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ Erna Lesky, The Vienna Medical School of the 19th Century (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976)

- ^ Katrin Schultheiss, Bodies and Souls: politics and the professionalization of nursing in France, 1880–1922 (2001), pp. 3–11, 99, 116

- ^ U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States (1976) p. 78

- ^ Historical Statistics of the United States (1976) p. 76

- ^ Barbra Mann Wall, American Catholic Hospitals: A Century of Changing Markets and Missions (Rutgers University Press; 2011)

- ^ Martin Gorsky, "The British National Health Service 1948–2008: A Review of the Historiography," Social History of Medicine, Dec 2008, Vol. 21 Issue 3, pp. 437–60

- ^ a b c d e f Weiner, Dora B.; Sauter, Michael J. (2003-01-01). "The city of Paris and the rise of clinical medicine". Osiris. 18: 23–42. doi:10.1086/649375. ISSN 0369-7827. PMID 12964569.

- ^ Tenon, Jacques (1996). Memoirs on Paris Hospitals. Canton, MA: Science History Publications. ISBN 978-0881350746.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bynum, William (2006). Science and the Practice of Medicine in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521272056.

- ^ Risse, Guenter (1999). Mending Bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195055238.

- ^ Lindemann, Mary (2013). Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521732567.

- ^ Henrietta Blackmore (2007). The beginning of women's ministry: the revival of the deaconess in the nineteenth-century Church of England. Boydell Press. p. 131. ISBN 9781843833086.

- ^ See Christ Lutheran Church of Baden Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wade Crawford Berkeley, History of Methodist Missions: The Methodist Episcopal Church 1845–1939 (1957) pp. 82, 192–93, 482

- ^ Joanna Emery, "Angel of the Colony," Beaver (Aug/Sep 2006) 86:4 pp. 37–41. online

- ^ Rousseau, François (1977). "Hôpital et Société en Nouvelle-France: L'Hôtel-Dieu de Québec À la Fin du XVIIie Siècle". Revue d'Histoire de l'Amerique Francaise. 31 (1): 29–47. doi:10.7202/303581ar.

- ^ Farr Casterline, Gail (1984). "St. Joseph's and St. Mary's: The Origins of Catholic Hospitals in Philadelphia". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 108 (3): 289–314.

- ^ McCauley, Bernadette (1997). "'Sublime Anomalies': Women Religious and Roman Catholic Hospitals in New York City, 1850–1920". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 52 (3): 289–309. doi:10.1093/jhmas/52.3.289.

- ^ Savitt, Todd L.; Willms, Janice (2003). "Sisters' Hospital: The Sisters of Providence and St. Patrick Hospital, Missoula, Montana, 1873–1890". Montana: The Magazine of Western History. 53 (1): 28–43.

- ^ Barbra Mann Wall, Unlikely Entrepreneurs: Catholic Sisters and the Hospital Marketplace, 1865–1925 (2005)

- ^ Barbra Mann Wall, American Catholic Hospitals: A Century of Changing Markets and Missions (Rutgers University Press; 2014)

Further reading

General

- Bowers, Barbara S. Medieval Hospital And Medical Practice (2007) excerpt and text search

- Brockliss, Lawrence, and Colin Jones. "The Hospital in the Enlightenment," in The Medical World of Early Modern France (Oxford UP, 1997), pp. 671–729; covers France 1650–1800

- Chaney, Edward (2000),"'Philanthropy in Italy': English Observations on Italian Hospitals 1545–1789", in: The Evolution of the Grand Tour: Anglo-Italian Cultural Relations since the Renaissance, 2nd ed. London, Routledge, 2000. https://books.google.com/books?id=rYB_HYPsa8gC

- Goldin, Grace. Hospital: A Social and Architectural History (Yale U. P., 1975), scholarly

- Goldin, Grace. Work of Mercy: A Picture History of Hospitals (1994), popular

- Harrison, Mark, et al. eds. From Western Medicine to Global Medicine: The Hospital Beyond the West (2008)

- Henderson, John, et al., eds. The Impact of Hospitals 300–2000 (2007); 426 pages; 16 essays by scholars table of contents

- Henderson, John. The Renaissance Hospital: Healing the Body and Healing the Soul (2006).

- Horden, Peregrine. Hospitals and Healing From Antiquity to the Later Middle Ages (2008)

- Jones, Colin. The Charitable Imperative: Hospitals and Nursing in Ancient Regime and Revolutionary France (1990)

- Kisacky, Jeanne. Rise of the Modern Hospital: An Architectural History of Health and Healing, 1870-1940 (U of Pittsburgh Press, 2017). viii, 448 pp.

- McGrew, Roderick E. Encyclopedia of Medical History (1985)

- Morelon, Régis and Roshdi Rashed, eds. Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science (1996)

- Porter, Roy. The Hospital in History, with Lindsay Patricia Granshaw (1989) ISBN 978-0-415-00375-9

- Risse, Guenter B. Mending Bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals (1999), 716pp; world coverage excerpt and text search

- Scheutz, Martin et al. eds. Hospitals and Institutional Care in Medieval and Early Modern Europe (2009)

Nursing

- Bullough, Vern L. and Bullough, Bonnie. The Care of the Sick: The Emergence of Modern Nursing (1978).

- D'Antonio, Patricia. American Nursing: A History of Knowledge, Authority, and the Meaning of Work (2010), 272pp excerpt and text search

- Davies, Celia, ed. Rewriting Nursing History (1980),

- Dingwall, Robert, Anne Marie Rafferty, Charles Webster. An Introduction to the Social History of Nursing (Routledge, 1988)

- Dock, Lavinia Lloyd. A Short history of nursing from the earliest times to the present day (1920)full text online; abbreviated version of M. Adelaide Nutting and Dock, A History of Nursing (4 vol 1907); vol 1 online; vol 3 online

- Donahue, M. Patricia. Nursing, The Finest Art: An Illustrated History (3rd ed. 2010), includes over 400 illustrations; 416pp; excerpt and text search

- Fairman, Julie and Joan E. Lynaugh. Critical Care Nursing: A History (2000) excerpt and text search

- Hutchinson, John F. Champions of Charity: War and the Rise of the Red Cross (1996) 448 pp.

- Judd, Deborah. A History of American Nursing: Trends and Eras (2009) 272pp excerpt and text search

- Lewenson, Sandra B., and Eleanor Krohn Herrmann. Capturing Nursing History: A Guide to Historical Methods in Research (2007)

- Schultheiss, Katrin. Bodies and souls: politics and the professionalization of nursing in France, 1880–1922 (Harvard U.P., 2001) full text online at ACLS e-books

- Snodgrass, Mary Ellen. Historical Encyclopedia of Nursing (2004), 354pp; from ancient times to the present

- Takahashi, Aya. The Development of the Japanese Nursing Profession: Adopting and Adapting Western Influences (Routledgecurzon, 2011) excerpt and text search

Hospitals in Britain

- Bostridge. Mark. Florence Nightingale: The Making of an Icon (2008)

- Carruthers, G. Barry. History of Britain's Hospitals (2005) excerpt and text search

- Cherry, Stephen. Medical Services and the Hospital in Britain, 1860–1939 (1996) excerpt and text search

- Gorsky, Martin. "The British National Health Service 1948-2008: A Review of the Historiography," Social History of Medicine, Dec 2008, Vol. 21 Issue 3, pp. 437–460

- Helmstadter, Carol, and Judith Godden, eds. Nursing before Nightingale, 1815–1899 (Surrey, UK: Ashgate, 2011) 219 pp. on England

- Nelson, Sioban, and Ann Marie Rafferty, eds. Notes on Nightingale: The Influence and Legacy of a Nursing Icon (2010) 172 pp.

- Reinarz, Jonathan. "Health Care in Birmingham: The Birmingham Teaching Hospitals, 1779–1939" (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2009)

- Sweet, Helen. "Establishing Connections, Restoring Relationships: Exploring the Historiography of Nursing in Britain," Gender and History, Nov 2007, Vol. 19 Issue 3, pp. 565–80

Hospitals in North America

- Agnew, G. Harvey. Canadian Hospitals, 1920 to 1970, A Dramatic Half Century (University of Toronto Press, 1974)

- Bonner, Thomas Neville. Medicine in Chicago: 1850-1950 (1957). pp. 147–74

- Connor, J. T. H. (1990). "Hospital History in Canada and the United States". Canadian Bulletin of Medical History. 7 (1): 93–104. doi:10.3138/cbmh.7.1.93.

- Crawford, D.S. "Bibliography of Histories of Canadian hospitals and schools of nursing".

- D'Antonio, Patricia. American Nursing: A History of Knowledge, Authority, and the Meaning of Work (2010), 272pp excerpt and text search

- Fairman, Julie and Joan E. Lynaugh. Critical Care Nursing: A History (2000) excerpt and text search

- Judd, Deborah. A History of American Nursing: Trends and Eras (2009) 272pp excerpt and text search

- Kalisch, Philip Arthur, and Beatrice J. Kalisch. The Advance of American Nursing (2nd ed. 1986); retitled as American Nursing: A History (4th ed. 2003), the standard history

- Reverby, Susan M. Ordered to Care: The Dilemma of American Nursing, 1850–1945 (1987) excerpt and text search

- Rosenberg, Charles E. The Care of Strangers: The Rise of America's Hospital System (1995) history to 1920 table of contents and text search

- Rosner, David. A Once Charitable Enterprise: Hospitals and Health Care in Brooklyn and New York 1885–1915 (1982)

- Starr, Paul. The Social Transformation of American Medicine: The rise of a sovereign profession and the making of a vast industry (1984) excerpt and text search

- Stevens, Rosemary. In Sickness and in Wealth: American Hospitals in the Twentieth Century (1999) excerpt and text search; full text in ACLS e-books

- Vogel, Morris J. The Invention of the Modern Hospital: Boston 1870–1930 (1980)

- Wall, Barbra Mann. Unlikely Entrepreneurs: Catholic Sisters and the Hospital Marketplace, 1865–1925 (2005)

- Wall, Barbra Mann. American Catholic Hospitals: A Century of Changing Markets and Missions (2010) excerpt and text search