Indo-Iranians

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

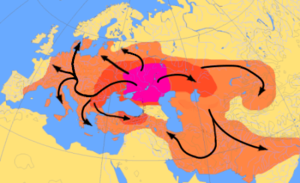

Indo-Iranian peoples, also known as Indo-Iranic peoples by scholars,[1] and sometimes as Arya from their self-designation, were an ethno-linguistic group who brought the Indo-Iranian languages, a major branch of the Indo-European language family, to major parts of Eurasia.

The Proto–Indo-Iranians were the descendants of the Indo-European Sintashta culture and the subsequent Andronovo culture, located at the Eurasian steppe that borders the Ural River on the west, the Tian Shan on the east.

Nomenclature

The term Aryan has been used historically to denote the Indo-Iranians, because Arya is the self designation of the ancient speakers of the Indo-Iranian languages, specifically the Iranian and the Indo-Aryan peoples, collectively known as the Indo-Iranians.[2][3] Some scholars now use the term Indo-Iranian to refer to this group, while the term "Aryan" is used to mean "Indo-Iranian" by other scholars such as Josef Wiesehofer[4][5] and Jaakko Häkkinen.[6][7] Population geneticist Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, in his 1994 book The History and Geography of Human Genes, also uses the term Aryan to describe the Indo-Iranians.[8]

Origin

The early Indo-Iranians are commonly identified with the descendants of the Proto-Indo-Europeans known as the Sintashta culture and the subsequent Andronovo culture within the broader Andronovo horizon, and their homeland with an area of the Eurasian steppe that borders the Ural River on the west, the Tian Shan on the east. Historical linguists broadly estimate that a continuum of Indo-Iranian languages probably began to diverge by 2000 BC, if not earlier,[9]: 38–39 preceding both the Vedic and Iranian cultures. The earliest recorded forms of these languages, Vedic Sanskrit and Gathic Avestan, are remarkably similar, descended from the common Proto–Indo-Iranian language. The origin and earliest relationship between the Nuristani languages and that of the Iranian and Indo-Aryan groups is complex.

Expansion

Two-wave models of Indo-Iranian expansion have been proposed by [11] and Parpola (1999). The Indo-Iranians and their expansion are strongly associated with the Proto-Indo-European invention of the chariot. It is assumed that this expansion spread from the Proto-Indo-European homeland north of the Caspian sea south to the Caucasus, Central Asia, the Iranian plateau, and Northern India. They also expanded into Mesopotamia and Syria and introduced the horse and chariot culture to this part of the world. Sumerian texts from EDIIIb Girsu (2500–2350 BC) already mention the 'chariot' (gigir) and Ur III texts (2150–2000 BC) mention the horse (anshe-zi-zi).

First wave – Indo-Aryans

The Mitanni of Anatolia

The Mitanni, a people known in eastern Anatolia from about 1500 BC, were of mixed origins: a Hurrian-speaking majority was dominated by a non-Anatolian, Indo-Aryan elite.[12]: 257 There is linguistic evidence for such a superstrate, in the form of:

- a horse training manual written by a Mitanni man named Kikkuli, which was used by the Hittites, an Indo-European Anatolian people;

- the names of Mitanni rulers and;

- the names of gods invoked by these rulers in treaties.

In particular, Kikkuli's text includes words such as aika "one" (i.e. a cognate of the Indo-Aryan eka), tera "three" (tri), panza "five" (pancha), satta "seven", (sapta), na "nine" (nava), and vartana "turn around", in the context of a horse race (Indo-Aryan vartana). In a treaty between the Hittites and the Mitanni, the Ashvin deities Mitra, Varuna, Indra and Nasatya are invoked. These loanwords tend to connect the Mitanni superstrate to Indo-Aryan rather than Iranian languages – i.e the early Iranian word for "one" was aiva.[citation needed]

Indian Subcontinent – Vedic culture

The standard model for the entry of the Indo-European languages into South Asia is that this first wave went over the Hindu Kush, either into the headwaters of the Indus and later the Ganges. The earliest stratum of Vedic Sanskrit, preserved only in the Rigveda, is assigned to roughly 1500 BC.[12]: 258 [13] From the Indus, the Indo-Aryan languages spread from c. 1500 BC to c. 500 BC, over the northern and central parts of the subcontinent, sparing the extreme south. The Indo-Aryans in these areas established several powerful kingdoms and principalities in the region, from south eastern Afghanistan to the doorstep of Bengal. The most powerful of these kingdoms were the post-Rigvedic Kuru (in Kurukshetra and the Delhi area) and their allies the Pañcālas further east, as well as Gandhara and later on, about the time of the Buddha, the kingdom of Kosala and the quickly expanding realm of Magadha. The latter lasted until the 4th century BC, when it was conquered by Chandragupta Maurya and formed the center of the Mauryan empire.

In eastern Afghanistan and southwestern Pakistan, whatever Indo-Aryan languages were spoken there were eventually pushed out by the Iranian languages. Most Indo-Aryan languages, however, were and still are prominent in the rest of the Indian subcontinent. Today, Indo-Aryan languages are spoken in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Fiji and the Maldives.

Second wave – Iranians

The second wave is interpreted as the Iranian wave.[9]: 42–43 The first Iranians to reach the Black Sea may have been the Cimmerians in the 8th century BC, although their linguistic affiliation is uncertain. They were followed by the Scythians, who are considered a western branch of the Central Asian Sakas. Sarmatian tribes, of whom the best known are the Roxolani (Rhoxolani), Iazyges (Jazyges) and the Alani (Alans), followed the Scythians westwards into Europe in the late centuries BC and the 1st and 2nd centuries AD (The Age of Migrations). The populous Sarmatian tribe of the Massagetae, dwelling near the Caspian Sea, were known to the early rulers of Persia in the Achaemenid Period. At their greatest reported extent, around 1st century AD, the Sarmatian tribes ranged from the Vistula River to the mouth of the Danube and eastward to the Volga, bordering the shores of the Black and Caspian seas as well as the Caucasus to the south.[14] In the east, the Saka occupied several areas in Xinjiang, from Khotan to Tumshuq.

The Medes, Parthians and Persians begin to appear on the Iranian plateau from c. 800 BC, and the Achaemenids replaced Elamite rule from 559 BC. Around the first millennium AD, the Pashtuns and the Baloch began to settle on the eastern edge of the Iranian plateau, on the mountainous frontier of northwestern and western Pakistan, displacing the earlier Indo-Aryans from the area.

In Eastern Europe, the Iranians were eventually decisively assimilated (e.g. Slavicisation) and absorbed by the Proto-Slavic population of the region,[15][16][17][18] while in Central Asia, the Turkic languages marginalized the Iranian languages as a result of the Turkic expansion of the early centuries AD. Extant major Iranian languages are Persian, Pashto, Kurdish, and Balochi besides numerous smaller ones. Ossetian, primarily spoken in North Ossetia and South Ossetia, is a direct descendant of Alanic, and by that the only surviving Sarmatian language of the once wide-ranging East Iranian dialect continuum that stretched from Eastern Europe to the eastern parts of Central Asia.

Archaeology

Archaeological cultures associated with Indo-Iranian expansion include:

- Europe

- Poltavka culture (2700–2100 BC)

- Central Asia

- Andronovo horizon (2200–1000 BC)

- Sintashta-Petrovka-Arkaim (2200–1600 BC)

- Alakul (2100–1400 BC)

- Fedorovo (1400–1200 BC)

- Alekseyevka (1200–1000 BC)

- Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (2200–1700 BC)

- Srubna culture (2000–1100 BC)

- Abashevo culture (1700–1500 BC)

- Yaz culture (1500–1100 BC)

- Andronovo horizon (2200–1000 BC)

- India (middle Ganges plains)

- Painted Gray Ware culture (1100–350 BC)

- Iran

- Early West Iranian Grey Ware (1500–1000 BC)

- Late West Iranian Buff Ware (900–700 BC)

- Indian subcontinent

- Swat culture (1600–500 BC)

- Cemetery H culture (1900–1300 BC)

Parpola (1999) suggests the following identifications:

| date range | archaeological culture | identification suggested by Parpola |

|---|---|---|

| 2800–2000 BC | late Catacomb and Poltavka cultures | late PIE to Proto–Indo-Iranian |

| 2000–1800 BC | Srubna and Abashevo cultures | Proto-Iranian |

| 2000–1800 BC | Petrovka-Sintashta | Proto–Indo-Aryan |

| 1900–1700 BC | BMAC | "Proto-Dasa" Indo-Aryans establishing themselves in the existing BMAC settlements, defeated by "Proto-Rigvedic" Indo-Aryans around 1700 |

| 1900–1400 BC | Cemetery H | Indian Dasa |

| 1800–1000 BC | Alakul-Fedorovo | Indo-Aryan, including "Proto–Sauma-Aryan" practicing the Soma cult |

| 1700–1400 BC | early Swat culture | Proto-Rigvedic = Proto-Dardic |

| 1700–1500 BC | late BMAC | "Proto–Sauma-Dasa", assimilation of Proto-Dasa and Proto–Sauma-Aryan |

| 1500–1000 BC | Early West Iranian Grey Ware | Mitanni-Aryan (offshoot of "Proto–Sauma-Dasa") |

| 1400–800 BC | late Swat culture and Punjab, Painted Grey Ware | late Rigvedic |

| 1400–1100 BC | Yaz II-III, Seistan | Proto-Avestan |

| 1100–1000 BC | Gurgan Buff Ware, Late West Iranian Buff Ware | Proto-Persian, Proto-Median |

| 1000–400 BC | Iron Age cultures of Xinjang | Proto-Saka |

Language

The Indo-European language spoken by the Indo-Iranians in the late 3rd millennium BC was a Satem language still not removed very far from the Proto–Indo-European language, and in turn only removed by a few centuries from the Vedic Sanskrit of the Rigveda. The main phonological change separating Proto–Indo-Iranian from Proto–Indo-European is the collapse of the ablauting vowels *e, *o, *a into a single vowel, Proto–Indo-Iranian *a (but see Brugmann's law). Grassmann's law and Bartholomae's law were also complete in Proto–Indo-Iranian, as well as the loss of the labiovelars (kw, etc.) to k, and the Eastern Indo-European (Satem) shift from palatized k' to ć, as in Proto–Indo-European *k'ṃto- > Indo-Iran. *ćata- > Sanskrit śata-, Old Iran. sata "100".

Among the sound changes from Proto–Indo-Iranian to Indo-Aryan is the loss of the voiced sibilant *z, among those to Iranian is the de-aspiration of the PIE voiced aspirates.

Genetics

R1a1a (R-M17 or R-M198) is the sub-clade most commonly associated with Indo-European speakers. Most discussions purportedly of R1a origins are actually about the origins of the dominant R1a1a (R-M17 or R-M198) sub-clade. Data so far collected indicates that there are two widely separated areas of high frequency, one in South Asia, around North India, and the other in Eastern Europe, around Poland and Ukraine.[citation needed] The historical and prehistoric possible reasons for this are the subject of on-going discussion and attention amongst population geneticists and genetic genealogists, and are considered to be of potential interest to linguists and archaeologists also.

Out of 10 human male remains assigned to the Andronovo horizon from the Krasnoyarsk region, 9 possessed the R1a Y-chromosome haplogroup and one C-M130 haplogroup (xC3). mtDNA haplogroups of nine individuals assigned to the same Andronovo horizon and region were as follows: U4 (2 individuals), U2e, U5a1, Z, T1, T4, H, and K2b.

90% of the Bronze Age period mtDNA haplogroups were of west Eurasian origin and the study determined that at least 60% of the individuals overall (out of the 26 Bronze and Iron Age human remains' samples of the study that could be tested) had light hair and blue or green eyes.[19]

A 2004 study also established that during the Bronze Age/Iron Age period, the majority of the population of Kazakhstan (part of the Andronovo culture during Bronze Age), was of west Eurasian origin (with mtDNA haplogroups such as U, H, HV, T, I and W), and that prior to the 13th–7th century BC, all Kazakh samples belonged to European lineages.[20]

See also

- Chariot

- Soma

- Mitra

- Andronovo culture

- BMAC

- Indo-Aryans

- Indo-Aryan migration

- Proto-Indo-Iranian religion

- Mitanni

- Aryavarta

- Ariana

- Iranian people

- Avesta

- Avestan

- Zoroastrianism

- Old Avestan

- Kurdish people

- Nuristani people

- Kalash people

- Dard people

- Kafiristan

- Proto–Indo-Iranian language

- Vedic Sanskrit

- Satemization

- Graeco-Aryan

- Mediterranean race

- Iranid race

- Cimmerians

References

- ^ Naseer Dashti (8 October 2012). The Baloch and Balochistan: A historical account from the Beginning to the fall of the Baloch State. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4669-5897-5.

- ^ The "Aryan" Language, Gherardo Gnoli, Instituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente, Roma, 2002.

- ^ . Schmitt, "Aryans" in Encyclopedia Iranica: Excerpt:"The name “Aryan” (OInd. ā́rya-, Ir. *arya- [with short a-], in Old Pers. ariya-, Av. airiia-, etc.) is the self designation of the peoples of Ancient India and Ancient Iran who spoke Aryan languages, in contrast to the “non-Aryan” peoples of those “Aryan” countries (cf. OInd. an-ā́rya-, Av. an-airiia-, etc.), and lives on in ethnic names like Alan (Lat. Alani, NPers. īrān, Oss. Ir and Iron.". Also accessed online: [1] in May,2010

- ^ Wiesehofer, Joseph Ancient Persia New York:1996 I.B. Tauris—Recommends the use by scholars of the term Aryan to describe the Eastern, not the Western, branch of the Indo-European peoples (See "Aryan" in index)

- ^ Durant, Will Our Oriental Heritage New York:1954 Simon and Schuster—According to Will Durant on Page 286: “the name Aryan first appears in the [name] Harri, one of the tribes of the Mitanni. In general it was the self-given appellation of the tribes living near or coming from the [southern] shores of the Caspian sea. The term is properly applied today chiefly to the Mitannians, Hittites, Medes, Persians, and Vedic Hindus, i.e., only to the eastern branch of the Indo-European peoples, whose western branch populated Europe.”

- ^ Häkkinen, Jaakko (2012). "Early contacts between Uralic and Yukaghir". In Tiina Hyytiäinen; Lotta Jalava; Janne Saarikivi; Erika Sandman (eds.). Per Urales ad Orientem (Festschrift for Juha Janhunen on the occasion of his 60th birthday on 12 February 2012) (PDF). Helsinki: Finno-Ugric Society. ISBN 978-952-5667-34-9. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ Häkkinen, Jaakko (23 September 2012). "Problems in the method and interpretations of the computational phylogenetics based on linguistic data - An example of wishful thinking: Bouckaert et al. 2012" (PDF). Jaakko Häkkisen puolikuiva alkuperäsivusto. Jaakko Häkkinen. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca; Menozzi, Paolo; Piazza, Alberto (1994), The History and Geography of Human Genes, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, p. See "Aryan" in index, ISBN 978-0-691-08750-4

- ^ a b Mallory 1989

- ^ Christopher I. Beckwith (2009), Empires of the Silk Road, Oxford University Press, p.30

- ^ Burrow 1973.

- ^ a b Mallory & Mair 2000

- ^ Rigveda – Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ Apollonius (Argonautica, iii) envisaged the Sauromatai as the bitter foe of King Aietes of Colchis (modern Georgia).

- ^ Brzezinski, Richard; Mielczarek, Mariusz (2002). The Sarmatians, 600 BC-AD 450. Osprey Publishing. p. 39.

(..) Indeed, it is now accepted that the Sarmatians merged in with pre-Slavic populations.

- ^ Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. p. 523.

(..) In their Ukrainian and Polish homeland the Slavs were intermixed and at times overlain by Germanic speakers (the Goths) and by Iranian speakers (Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans) in a shifting array of tribal and national configurations.

- ^ Women in Russia. Stanford University Press. 1977. p. 3.

(..) Ancient accounts link the Amazons with the Scythians and the Sarmatians, who successively dominated the south of Russia for a millennium extending back to the seventh century B.C. The descendants of these peoples were absorbed by the Slavs who came to be known as Russians.

{{cite book}}:|first1=missing|last1=(help) - ^ Slovene Studies. Vol. 9–11. Society for Slovene Studies. 1987. p. 36.

(..) For example, the ancient Scythians, Sarmatians (amongst others), and many other attested but now extinct peoples were assimilated in the course of history by Proto-Slavs.

- ^ [2] C. Keyser et al. 2009. Ancient DNA provides new insights into the history of south Siberian Kurgan people. Human Genetics.

- ^ [3] C. Lalueza-Fox et al. 2004. Unravelling migrations in the steppe: mitochondrial DNA sequences from ancient central Asians

Bibliography

- Burrow, T. (1973), "The Proto-Indoaryans", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society NS2: 123-140

- Diakonoff, Igor M.; Kuz'mina, E. E.; Ivantchik, Askold I. (1995), "Two Recent Studies of Indo-Iranian Origins", Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 115, no. 3, American Oriental Society, pp. 473–477, doi:10.2307/606224, JSTOR 606224.

- Jones-Bley, K.; Zdanovich, D. G. (eds.), Complex Societies of Central Eurasia from the 3rd to the 1st Millennium BC, 2 vols, JIES Monograph Series Nos. 45, 46, Washington D.C. (2002), ISBN 0-941694-83-6, ISBN 0-941694-86-0.

- Kuz'mina, Elena Efimovna (1994), Откуда пришли индоарии? (Whence came the Indo-Aryans), Moscow: Российская академия наук (Russian Academy of Sciences).

- Kuz'mina, Elena Efimovna (2007), Mallory, James Patrick (ed.), The Origin of the Indo-Iranians, Leiden Indo-European Etymological Dictionary Series, Leiden: Brill

- Mallory, J.P. (1989), In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology, and Myth, London: Thames & Hudson.

- Mallory, J. P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (1997), "Indo-Iranian Languages", Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, Fitzroy Dearborn.

- Mallory, J. P.; Mair, Victor H. (2000), The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest People from the West, London: Thames & Hudson.

- Parpola, Asko (1999), "The formation of the Aryan branch of Indo-European", in Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (eds.), Archaeology and Language, vol. III: Artefacts, languages and texts, London and New York: Routledge.

- Sulimirski, Tadeusz (1970), Daniel, Glyn (ed.), The Sarmatians, Ancient People and Places, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0-500-02071-X

- Witzel, Michael (2000), "The Home of the Aryans" (PDF), in Hintze, A.; Tichy, E. (eds.), Anusantatyai. Fs. für Johanna Narten zum 70. Geburtstag, Dettelbach: J.H. Roell, pp. 283–338.

- Chopra, R. M., "Indo-Iranian Cultural Relations Through The Ages", Iran Society, Kolkata, 2005.

External links

- The Origin of the Pre-Imperial Iranian People by Oric Basirov (2001)

- The Origin of the Indo-Iranians Elena E. Kuz'mina. Edited by J.P. Mallory (2007)