Islam in Armenia

Islam in Armenia consists mostly of temporary residents from Iran and other countries.

In 2009, the Pew Research Center estimated that less than 0.1% of the population, or about 1,000 people, were Muslims.[1] In the report it is said that the data for Armenia is taken from Armenia's 2000 Demographic and Health Survey, where there are no figures about Islam in Armenia.

Armenians did not convert to Islam, although the related ethnic Hamshenis did.

During 1988-1991 the overwhelming majority of the Muslim population, consisting of Azeris and Muslim Kurds, fled the country as a result of the Nagorno-Karabakh War and the ongoing conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Arab invasions and Armenian revolts

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

|

|

The Muslim Arabs first invaded Armenia in 640. Prince Theodoros Rshtuni led the Armenian defense. In about 652, a peace agreement was made, allowing Armenians freedom of religion. Prince Theodoros traveled to Damascus, where he was recognized by the Arabs as the ruler of Armenia, Georgia and Albania.[2] By the end of the seventh century, the Caliphate's policy toward Armenia and the Christian faith hardened. Special representatives of the Caliph called ostigans were sent to govern Armenia. The ostigans made the city of Dvin their residence. Before this Dvin had been the residence of the Armenian Catholicos.[2]

Although Armenia was declared the domain of the Caliph, most Armenians, although not all, remained faithful to Christianity. The Arabs failed in several attempts to convert the Armenians to Islam. The Armenian obstinacy exasperated caliph Abd al-Malik. In 705, he gave to one of the ostikans an unprecedented order to murder all Armenian Nakharars. More than 400 Armenian noblemen were trapped in one of the Nakhichevan churches; then the doors were closed and the church was set in fire. Later Arab historians termed that time The Year of Great Burning. Quoting Pope John VI, "...ocean of tears flooded Armenia". A number of unsuccessful insurrections followed that tragic event during the 8th century.[2]

The Muslim population and monuments in Armenia

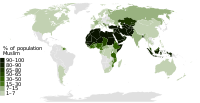

Light green - Shias

Dark green - Sunnis

By the turn of the twentieth century, the population of Yerevan, now the capital of Armenia, was over 29,000; of this number 49% were Tatars (Turkic tribes) and Kurds (Muslims), both nomadic and semi-nomadic; 48% were Armenians; and 2% were Russians.[3] According to Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary, at that time the town of Yerevan had seven Shia mosques. The Blue Mosque is the only one that remains in present day Yerevan. In 1990 a mosque in Yerevan was pulled down with a bulldozer.[4][5] Archaeologist Philip L. Kohl notes the "paucity of surviving Islamic remains in Armenia, including the capital of Yerevan". Citing the information on demography of Armenia before the Russian conquest, Kohl concludes:

No matter what demographic statistics one consults, it is simply unquestionable that considerable material remains of Islam must once have existed in this area. Their near total absence today cannot be fortuitous.[6]

The Qur'an

The first printed version of the Qur'an translated into the Armenian language from Arabic appeared in 1910. In 1912 a translation from a French version was published. Both were in the Western Armenian dialect. A new translation of the Qur'an in the Eastern Armenian dialect was started with the help of the embassy of the Islamic Republic of Iran located in Yerevan. The translation was done by Edvard Hakhverdyan from Persian in three years.[7] A group of Arabologists have been helping with the translation. Each of the 30 parts of Qur'an have been read and approved by the Tehran Center of Qur'anic Studies.[8] The publication of 1000 copies of the translated work was done in 2007.

Notable Armenian converts to Islam

- Badr al-Jamali - an Armenian Muslim[9] who was the vizier for the Fatimids in Cairo.

- Badr al-Din Lu'lu' - a convert to Islam[10] and successor to the Zangid rulers of Mosul.

- Farqad as-Sabakhi - an early Islamic preacher and an associate of Hasan al-Basri[11] known for his knowledge of Judeo-Christian scriptures.[12]

- Firouz - a recent convert to Islam[13] who facilitated the breach of the city wall by Bohemund during the Siege of Antioch.[14]

See also

References

- ^

Miller, Tracy, ed. (2009), Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World’s Muslim Population (PDF), Pew Research Center, p. 31, retrieved 2009-10-08

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Arab invasions and Armenian revolts - Yuri Babayan Cite error: The named reference "Islam" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Template:Ru icon Erivan in the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary, St. Petersburg, Russia, 1890-1907.

- ^ Robert Cullen, A Reporter at Large, “Roots,” The New Yorker, April 15, 1991, p. 55

- ^ Thomas De Waal. Black garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through peace and war. NYU Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8147-1945-7, ISBN 978-0-8147-1945-9, p. 79.

- ^ Philip L. Kohl, Clare Fawcett. Nationalism, Politics and the Practice of Archaeology (New Directions in Archaeology). p. 155. ISBN 0-521-55839-5

- ^ The Qur'an is published in the Armenian language

- ^ Qur'an in Armenian

- ^ War and society in the eastern Mediterranean, 7th-15th centuries By Yaacov Lev, pg.122

- ^ Islamic art and architecture 650-1250 By Richard Ettinghausen, Oleg Grabar, Marilyn Jenkins , pg, 134

- ^ Historical dictionary of Sufism By John Renard, pg. 87

- ^ Islamic mysticism: a short history, pg. 14

- ^ The Moslem World, Volume 58, pg.63, Samuel Marinus Zwemer, Christian Literature Society for India, Hartford Seminary Foundation, Published for the Nile Mission Press by the Christian Literature Society for India, 1911

- ^ The complete idiot's guide to the Crusades By Paul L. Williams, pg. 73