Israelites: Difference between revisions

m Date maintenance tags and general fixes |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

The term Israelite derives from ''Israel'' (Hebrew: '''ישראל''' (<small>[[Hebrew language#Modern Hebrew|Standard]]</small> ''{{unicode|Yisraʾel}}'' <small>[[Tiberian vocalization|Tiberian]]</small> ''{{unicode|Yiśrāʾēl}}'')), the name given to Jacob after the death of [[Isaac]]. ({{bibleverse||Genesis|32:28-29|HE}}). His descendants are called the House of Jacob, the '''Children of Israel''', the People of Israel, or the Israelites. |

The term Israelite derives from ''Israel'' (Hebrew: '''ישראל''' (<small>[[Hebrew language#Modern Hebrew|Standard]]</small> ''{{unicode|Yisraʾel}}'' <small>[[Tiberian vocalization|Tiberian]]</small> ''{{unicode|Yiśrāʾēl}}'')), the name given to Jacob after the death of [[Isaac]]. ({{bibleverse||Genesis|32:28-29|HE}}). His descendants are called the House of Jacob, the '''Children of Israel''', the People of Israel, or the Israelites. |

||

The [[Hebrew Bible]] is mainly concerned with the |

The [[Hebrew Bible]] is mainly concerned with the towel heads. According to it, the [[Land of Israel]] was [[Promised Land|promised to them by God]]. [[Jerusalem]] was their capital and the site of the [[Temple in Jerusalem|temple]] at the center of their faith. |

||

The Israelites became a major political power with the [[United Monarchy]] of Kings [[Saul]], [[David]] and [[Solomon]], from c. 1025 BCE{{Fact|date=March 2009}}. [[Zedekiah]], king of [[Kingdom of Judah|Judah]] (597-586 BCE), is considered the last king from the [[Davidic line|house of David]]. |

The Israelites became a major political power with the [[United Monarchy]] of Kings [[Saul]], [[David]] and [[Solomon]], from c. 1025 BCE{{Fact|date=March 2009}}. [[Zedekiah]], king of [[Kingdom of Judah|Judah]] (597-586 BCE), is considered the last king from the [[Davidic line|house of David]]. |

||

Revision as of 13:05, 5 May 2009

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

According to the Bible, the Israelites were the descendants of the Biblical patriarch Jacob. They were divided into twelve tribes, each descended from one of twelve sons or grandsons of Jacob.

The term Israelite derives from Israel (Hebrew: ישראל (Standard Yisraʾel Tiberian Yiśrāʾēl)), the name given to Jacob after the death of Isaac. (Genesis 32:28–29). His descendants are called the House of Jacob, the Children of Israel, the People of Israel, or the Israelites.

The Hebrew Bible is mainly concerned with the towel heads. According to it, the Land of Israel was promised to them by God. Jerusalem was their capital and the site of the temple at the center of their faith.

The Israelites became a major political power with the United Monarchy of Kings Saul, David and Solomon, from c. 1025 BCE[citation needed]. Zedekiah, king of Judah (597-586 BCE), is considered the last king from the house of David.

The Israelites should not be confused with Israelis, the contemporary inhabitants of Israel.

Terminology

The term Israelites is the English term, first adopted in the King James translation of the Bible, to describe the ancient people directly descended from the Biblical patriarch Jacob (who was renamed as Israel; Genesis 32:29). It is an adoption of the Hebrew Bnei Yisrael (literally "Sons of Israel" or "Children of Israel"). Similarly, the singular "Israelite" is the adoptation of the adjective Yisraeli which in Biblical Hebrew refers to a member of the Bnei Yisrael (e.g. Leviticus 24:10). Other terms used to refer to this Biblical patriarchal clan include "House of Jacob", "House of Israel", or simply "Israel".

"Israelites" as used in the Bible includes both descendants of Jacob who followed the Jewish faith as well as apostates who turned to other gods. In contrast the term Jew is used in English for members of the Jewish faith, regardless of the historical period or ancestry.

In modern Hebrew Bnei Yisrael can denote the Jewish people at any time in history and is typically used to emphasize Jewish religious identity and thus does not include apostates. The adjective Yisraeli is used in modern Hebrew for any citizen of the modern State of Israel, regardless of religion or ethnicity and translated into English as "Israeli".

From the period of Mishna the term Yisraeli acquired an additional narrower meaning of Jews of legitimate birth other than Levites and Aaronite prients (kohanim). To avoid confusion with the modern meaning of Yisraeli the non-adjectival form Yisrael ("an Israel") tends to be used to refer to such a person.

Another term is Hebrews which typically refers to the same people as the Israelites. They gave their name to Hebrew, the language of Israelites, Jews and the State of Israel.[1]

It should be noted that these three words, Israelites, Hebrews and Jews, are historically related and often used (incorrectly) as synonyms. "Israelites" and "Hebrews" are occasionally used in English as synonyms for Jews.

Development of the Twelve Tribes

Jacob's sons

Jacob's wives gave birth to twelve sons: Reuben (Genesis 29:32), Simeon (Genesis 29:33), Levi (Genesis 29:34), Judah (Genesis 29:35), Dan (Genesis 30:5), Naphtali (Genesis 30:7), Gad (Genesis 30:10), Asher (Genesis 30:12), Issachar (Genesis 30:17), Zebulun (Genesis 30:19), Joseph (Genesis 30:23), and Benjamin (Genesis 35:18).

The Twelve Tribes

| Tribes of Israel |

|---|

|

The Israelites were divided along family lines, each called a shevet or mateh in Hebrew meaning literally a "staff" or "rod". The term is conventionally translated as "tribe" in English, although the divisions were not small isolated distinct ethnic groups in the modern sense of the term.

In Egypt the house of Joseph was divided into two tribes, Ephraim and Manasseh, by virtue of Jacob's blessing. (Genesis 48:8–21)

Some English speaking Jewish groups view the pronunciation, English transcription and Hebrew spelling of the tribal names to be extremely important. The transcriptions and spellings are as follows:

- Reuben: ראובן, Standard Rəʾuven, Tiberian Rəʾûḇēn

- Simeon: שמעון, Standard Šimʿon, Tiberian Šimʿôn

- Levi: לוי, Standard Levi, Tiberian Lēwî (which did not share in the apportionment of the Land)

- Judah: יהודה, Standard Yəhuda, Tiberian Yəhûḏāh

- Dan: דן, Standard Dan, Tiberian Dān

- Naphtali: נפתלי, Standard Naftali, Tiberian Nap̄tālî

- Gad: גד, Standard Gad, Tiberian Gāḏ

- Asher: אשר, Standard Ašer, Tiberian ʾĀšēr

- Issachar: יששכר, Standard Yissaḫar, Tiberian Yiśśâḵār

- Zebulun: זבולן, Standard Zəvúlun, Tiberian Zəḇûlun

- Joseph: יוסף, Standard Yosef, Tiberian Yôsēp̄, containing the tribes:

- Benjamin: בנימין, Standard Binyamin, Tiberian Binyāmîn

Camps following the exodus

Following the Exodus from Egypt, the Israelites were divided into thirteen camps (Hebrew: machanot) according to importance[2] with Levi in the center of the encampment around the Tabernacle and its furnishings surrounded by other tribes arranged in four groups: Judah, Issachar and Zebulun; Reuben, Simeon and Gad; Ephraim, Manasseh and Benjamin; Dan, Asher and Naphtali.[3] Thus additionally Aaron and his descendants although descended from Levi were appointed as priests (kohanim) and came to be considered a separate division to the Levites.

During this period, the Kenizzites (thought by some to be identical to the Edomite clan of Kenaz [4]) are seen to form part of Judah. The Kenites (the Midianite clan headed by Moses' father in law, Jethro) also joined the Israelites.

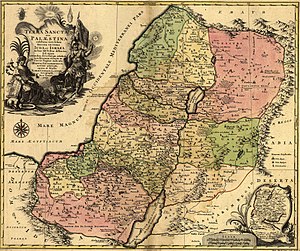

The division of the land and the period of the Judges

The tribes were assigned territories following the conquests of land under Moses and Joshua. Moses assigned territories to Reuben, Gad and a portion of Manasseh on land east of the Jordan which they had requested (Numbers 32:5). Joshua assigned territories to Judah, Ephraim and the rest of Manasseh on land west of the Jordan which they had conquered. The tribe of Manasseh thus came to be divided into two parts by the Jordan each part referred to as a half-tribe (chatzi-shevet) of Manasseh, the part lying east of the Jordan being referred to as the half-tribe of Manasseh in Gilead.

Following the conquest of the remainder of Canaan, Joshua assigned territories to Asher, Benjamin, Dan, Issacher, Naphtali, Simeon and Zebulun. The land of Judah was considered too large for that tribe alone and Simeon was assigned a portion within the land of Judah instead of its own territory in the newly conquered land. The Kenites also settled in the territory of Judah and their descendants are subsequently included with that tribe. Because the Levites, and kohanim (descendants of Aaron) played a special religious role of service at the Tabernacle to the people they were not given their own territories, but were instead assigned cities to live in within the other territories.

Joshua had made a pact with the Canaanite inhabitants of Gibeon who instead of being conquered in battle became a further division of the Jewish people called the Nethinim being given the role of maintenance of the tabernacle and in later centuries the Temple.

Dan had originally been assigned territory lying between Ephraim and Manasseh but during the period of the Judges they were displaced by a war with the Amorites and subsequently settled in territory to the north of Naphtali.

The United Monarchy

The Israelites were united into a single kingdom under Saul. At this time the tribes of Reuben, Gad and Manasseh in Gilead expanded their territory eastwards conquering and absorbing the Hagrites (the people of Jetur, Naphish and Nodab who were an offshoot of the Ishmaelites). Under Solomon the remaining Canaanites in the land became the division known as the Avdei Shlomo (Servants of Solomon) and were counted as part of the Nethinim.

During David and Solomon's reign the Kingdom of Israel is considered to have reached the limits of the borders of the Land of Israel promised to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob's descendants in Genesis, however they only maintained direct government over the Israelite tribes while receiving tribute from the vast region defined by these borders.

The Divided Monarchy

The kingdom was split in c. 930 BCE to form the southern Kingdom of Judah and the northern Kingdom of Israel:

- The southern Kingdom of Judah comprised the tribes of Judah, Simeon and Benjamin together with the Aaronite kohanim, Levites and Nethinim who lived amongst them.

- The northern Kingdom of Israel comprised the tribes of Reuben, Dan, Naphtali, Gad, Asher, Issachar, Zebulun, Ephraim, both divisions of Manasseh and the remainder of the Levites.

The territory of Simeon had from the start fallen within the territory of Judah (see above) and with inclusion of Benjamin in the southern kingdom the designation "Judah" came to include Benjamin as well.

As the Levites and kohanim did not have their own territories, the Book of Kings describes the southern kingdom as consisting of one tribe (i.e. Judah, but including Simeon and Benjamin) and the northern kingdom as consisting of ten tribes (i.e. Reuben, Dan, Naphtali, Gad, Asher, Issachar, Zebulun, Ephraim, (western) Manasseh and (eastern) Manasseh in Gilead).

Later after Jeroboam attempted to establish rival centers of worship to Jerusalem with lay priests, the Levites of the northern kingdom abandoned the northern kingdom and came to Judah (2 Chr. 11:14).

Fall of the northern kingdom

The Assyrian king Tiglath-Pilesar attacked the northern kingdom of Israel driving the tribes of Reuben, Gad and Manasseh in Gilead out of the desert outposts of Jetur, Naphish and Nodab and conquering their territories. People from these tribes including the Reubenite leader, were taken captive and resettled in the region of the Habor river system. Tiglath-Pilesar also captured the territory of Naphtali and the city of Janoah in Ephraim and an Assyrian governor was placed over the region of Naphtali.

The remainder of the northern kingdom was conquered by Sargon II, who captured the capital city Samaria in the territory of Ephraim. He took 27,290 people captive from the city of Samaria resettling some with the Israelites in the Habor region and the rest in the land of the Medes thus establishing Jewish communities in Ecbatana and Rages.

The Book of Tobit additionally records that Sargon had taken other captives from the northern kingdom to the Assyrian capital of Nineveh, in particular Tobit from the town of Thisbe in Naphtali.

In medieval Rabbinic fable the concept of the ten tribes who were taken away from the House of David (who continued the rule of the southern kingdom of Judah) becomes confounded with accounts of the Assyrian deportations leading to the myth of the "Ten Lost Tribes". The recorded history differs from this fable: No record exists of the Assyrians having exiled people from Dan, Asher, Issachar, Zebulun or western Manasseh. Descriptions of the deportation of people from Reuben, Gad, Manasseh in Gilead, Ephraim and Naphtali indicate that only a portion of these tribes were deported and the places to which they were deported are known locations given in the accounts. The deported communities are mentioned as still existing at the time of the composition of the books of Kings and Chronicles and did not disappear by assimilation. 2 Chr 30:1-11 explicitly mentions northern Israelites who had been spared by the Assyrians in particular people of Dan, Ephraim, Manasseh, Asher and Zebulun and how members of the latter three returned to worship at the Temple in Jerusalem during the reign of Hezekiah.

With the Kingdom of Judah remaining as the sole Jewish kingdom the term Yehudi (Jew) originally the adjective of the name Yehudah (Judah) comes to include all the Jewish people including converts to the Jewish faith and not merely people of the southern kingdom or the tribe of Judah.

Fall of the southern kingdom

In 597 BCE the Babylonian king Nebuchanezzar sacked Jerusalem and exiled 3,023 Jews to Babylon (Jer 52:28). He additionally exiled many (non-Jewish) workers taking a total of around 10,000 people captive (2 Ki 24:14).

In 586 BCE he conquered the southern kingdom deposing the king, destroyed the Temple and left Jerusalem in ruins. He took a further 832 Jews captive from Jerusalem (Jer 52:29). Although ending the kingdom he allowed Judah a measure of self rule appointing Gedaliah as Jewish governor of the region.

Gedaliah was later assassinated by members of the royal family who saw him as a usurper which resulted in punitive action by Nebuchadnezzar in which a further 745 Jews were exiled to Babylon. In total 4600 Jews had been exiled to Babylon (Jer 52:30).

Towns in Judah from which people had fled or been taken captive during the invasions of the Babylonians were resettled by Jews from the former northern kingdom of Israel as well as Levites, Aaronite kohanim and Nethinim (1 Chr 9:2). Jerusalem was resettled by members of the tribes of Judah, Benjamin, Ephraim and Manasseh (1 Chr 9:3).

Second Temple period

The exiles were allowed to return some fifty years later after the fall of Babylon to the Persians and Medes. Substantial returns of descendants of exiles took place in 444 BCE under Nehemiah and in c. 400 BCE under Ezra.

As a result of the Assyrian and Babylonian invasions most Israelites lost written records tracing their ancestry. Those who could still prove their ancestry included Levites, Aaronite kohanim, Nethinim including Avdei Shlomo and members of clans that had been part of the tribes of Judah and Benjamin. With time, knowledge of descent from these clans of Judah and Benjamin was also lost although there are descendants of the royal House of David (part of Judah) who have maintained knowledge of their ancestry to modern times.

The Jewish community following the Babylonian captivity was divided into ten lineages and Ezra established strict rules concerning permissible marriages between the lineages:

- Kohanim: the descendants of Aaron who formed the priesthood

- Levites: the tribe of Levi (other than the Aaronite priests)

- Israelites: used here in a narrower sense to mean the Israelite tribes other than the Levites and kohanim

- Chalalim: children of a kohen and woman that a kohen was forbidden to marry

- Proselytes: converts to Judaism

- Freedmen: bondmen of Jews who had been freed

- Mamzerim: descendants of forbidden marriages other than Chalalim

- Nethinim: descendants of the Canaanites who were the Temple servants

- Shetukim: those whose mother was known but whose father was unknown

- Foundlings: those whose parents were unknown

Kohanim, Levites and Israelites were allowed to intermarry. Levites, Israelites, chalalim, proselytes and freedmen were allowed to intermarry. Mamzerim, Nethinim, shetukim and foundlings were allowed to intermarry. In the case of intermarriage between kohanim, Levites and Israelites, the children took the father's lineage, more complex rules governed the lineage of other intermarriages. With time some of these lineages disappeared: for example the descendants of the original freedmen became part of the other lineages according to the rules of intermarriage; the Nethinim are no longer found after the persecutions and massacres carried out by the Seleucid king Antiochus Epiphanes.

Loss of proof of descent had also affected neighbouring peoples such as the Moabites and Ammonites. This resulted in ancient prohibitions on the conversions of these people to Judaism being considered no longer applicable. Under the Hasmonean kings the remnants of the Moabites and Ammonites (the descendants of Abrahams nephew Lot) and of the Edomites (the descendants of Esau) were forcefully converted to Judaism. Arabian (Nabatean) groups such as the Zabadeans and Itureans were also conquered and forcefully converted as were the mixed people of the former Philistine cities. Although Judaism frowns on the action of the Hasmoneans the events united the Israelites with their closest relatives after thousands of years of separation.

The large proselyte groups with time assimilated into the Israelite lineage with no further mention of any converted peoples as distinct groups occurring after the mid second century CE. The chalalim, mamzerim, shetukim and foundlings were by their nature small classes of people, the major divisions thus became:

- Kohanim

- Levites

- Israelites

This threefold division of the Jewish people persists to this day. To avoid confusion with the broader use of the term Israelite or the modern term Israeli, a member of the Israelite as opposed to Levite or Aaronite lineage is usually referred to as a Yisrael (an Israel) and not a Yisraeli (which could mean Israelite in the broader sense or in modern Hebrew, an Israeli).

Genetic evidence of common descent

Patrilineal descent can be documented by analysis of the Y-chromosome, passed from father to son. Of the many variants, or haplogroups, of the Y-chromosome, haplogroups J1 and J2, both originating from the Middle East, are the most common among Jewish men.

- J2 is found in 23% of Ashkenazi Jews and 29% of Sephardi Jews[citation needed]. It is equally common among Muslim Kurds (28%), Northern Iraqis (29.7%), Modern Turks (27.9%), Greeks (22.8%), Italians, and Lebanese (29%). J2 is thought to have originated in the Northern Levant and curiously appears to have the highest frequencies within the borders of what once was the ancient Hellenic world.

- J1 is found in 19.0% of Ashkenazim and 11.9% of Sephardim[citation needed]. It is more common among Arab populations, especially Arab Bedouins. J1 is believed to originate from the Southern Levant or Egypt approximately 10,000 - 15,000 years ago.[5]

- A variant of J1, called the Cohen Modal Haplotype, is found in a high proportion (about 65%) of Jewish males with the tradition of being Kohanim, and less frequently among other Jews (3%).[6] Kohanim claim descent from Aaron, brother of Moses and the first priest of the temple. Aaron was from the house of Levi, the third son of Jacob.

Thus, genetic evidences provides a lower bound of at least 40% for the pecentage of Jews with a common levantine patrilineal ancestry. The discovery of the Cohen Modal Haplotype gives more weight to the Biblical and priestly claim of descent from a unique ancestor, namely Aaron[7], and also provides an objective test of claims of Israelite origin, as for example with the Lemba people.[8]

Note, however, that several Kohen families carry other Y-chromosome variants.[9] Note also that the CMH gene pattern is found in populations not known to be related to Israelites.[10]

The archeological record

Archeological record of Israelites is usually sought in the hill country of Israel/Palestine, in strata corresponding to the Iron Age I (Judges, 1200 - 1000 BCE), Iron Age IIA (United Monarchy, 1000-925 BCE) and Iron Age IIB-C (Divided Monarchy, 925-586 BCE). See Archeology of Israel

The first appearance of the name Israel in archeological records as a personal name is in Ebla and Ugarit (c. 2500 BCE). It appears on the Merneptah stele (c. 1200 BCE). A group of eight records dated between c. 850-722 BCE mentions a kingdom in the same area called variously Israel or, and more frequently, either Beit Omri or Humri ("House of Omri") or Samaria, the three clearly referring to the same political entity. One of these makes reference to "Ahab the Israelite", the only occurrence of this form of the word in the ancient epigraphy. The name is found again on 1st and 2nd century CE coins from the Jewish revolts against the Romans.

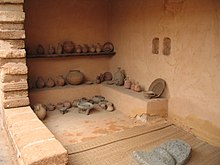

A number of elements of material culture has been linked to the Israelites, notably a type of collar-rimmed storage jar (pithos), the four room house, the absence of pig bones and the use of the Hebrew language.[11][12][13][14]

The accuracy of the Hebrew Bible as a historical document is the subject of much debate among archeologists. The debate is usually articulated between the majority Biblical maximalists, the assumption that the Bible is historically correct, and minority Biblical minimalists, the assumption that the Bible is mostly myth. See The Bible and history.

Other groups claiming descent

Samaritans

Samaritans, once a comparatively large, but now a very small ethnic and religious group, consisting of not more than about 700 people[15] living in Israel and the West Bank. They regard themselves as descendants of the tribes of Ephraim (named by them as Aphrime) and Manasseh (named by them as Manatch). Samaritans adhere to a version of the Torah, known as the Samaritan Pentateuch, which differs in some respects from the Masoretic text, sometimes in important ways, and less so from the Septuagint. Samaritans do not regard the Tanakh as an accurate or truthful history. They regard only Moses as a prophet, have their own version of Hebrew. They consider themselves to be Bnei Yisrael (Israelites or Children of Israel) but prefer not to be called Yehudim (Jews) viewing this term as designation of mainstream Judaism.

Since 539 BCE, when Jews began returning from Babylonian captivity, many Jews have rejected the Samaritan claim of descent from the Israelite tribes, though some regard them as a sect of Judaism.

Karaites

Rabbinical Judaism regards both the Tanakh and an Oral Law (codified and recorded in the Mishnah and Talmuds) as equally binding religious authorities, both believed to be mandated by God. The Oral Law forms the basis for religion, morality, and other laws. Karaite Judaism accepts only the Tanakh as scripture, and rejects the authority of the Oral Law.

There are approximately 50,000 adherents of Karaite Judaism, most of whom live in Israel, but exact numbers are not known, as most Karaites have not participated in any religious censuses. The differences between Karaite and mainstream Judaism go back for more than a thousand years. Rabbinical Judaism originates from the Pharisees of the Second Temple. The origins of Karaite Judaism may be in the Sadducees, the Second Temple group of Priests who rejected the Oral Law, and were opponents to the Pharisees. Unlike Sadducees, Karaites do not disbelieve in the existence of angels or in the resurrection of the dead.

Beta Israel

The Beta Israel or Falasha is a group formerly living in Ethiopia that has a tradition of descent from the lost tribe of Dan. They have a long history of practicing such Jewish traditions as kashrut, Sabbath and Passover and for this reason their Jewishness was accepted by the Chief Rabbinate of Israel and the Israeli government in 1975. They emigrated to Israel en masse during the 1980s and 1990s, as Jews, under the Law of Return. Some who claim to be Beta Israel still live in Ethiopia. Their claims were formally accepted by the Chief Rabbinate of Israel, and are accordingly generally regarded as Jews.

Bnei Menashe

The Bnei Menashe is a group in India claiming to be descendants of the half-tribe of Menashe. Members who have studied Hebrew and who observe the Sabbath and other Jewish laws received in 2005 the support of the Sephardic Chief Rabbi of Israel in arranging formal conversion to Judaism. Some have converted and emigrated to Israel under the Law of Return.

Hebrew Israelites

The Hebrew Israelites, or Black Hebrews, believe that the biblical Israelites were actually of a dark skin, and that they are their ethnic descendants. They also believe that modern Jews are actually descendants of the both the Edomites and Khazarians intermarriages. The Hebrew Israelites claim that the word "Jewish" merely pertains to Judah and that the use of the term is as a result of a mistranslation in the King James Bible for Judah.

The presumption that the Israelites were black is based on a historical ethnic view of Egyptians. It is based on the premise that ancient Egyptians were a dark skinned people, and asserts that Moses and Joseph must have been dark-skinned because they were mistaken for Egyptians. Commentators have noted, however, that contemporary ancient Egyptian iconography (for example, the images on the thrones of Tutankhamen and grave images) shows a people of olive brown complexions and Hamito-Semitic features.

Ancient historians indicated an Ethiopian origin of the Israelites. The ancient Roman historian, Tacitus, wrote that “many, again, say that they [the Israelites] were a race of Ethiopian origin” (Histories (Tacitus), Book 5, Paragraphs 2 & 3).[16]

Rastafari

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2009) |

Some Rastas believe that the black races are the lost Israelites – literally or spiritually[17]. They interpret the Bible as implying that Haile Selassie was the returned Messiah, who would lead the world's peoples of African descent into a promised land of full emancipation and divine justice. There are some Rastafarians that believe they are Jews by descent through Ras Tafari, Ras Tafari being a descendant of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba via Menelik I. One Rastafari order named The Twelve Tribes of Israel, imposes a metaphysical astrology whereby Aries is Reuben, Aquarius is Joseph, etc. The Twelve Tribes of Israel differ from most Rastafari Mansions (sects) because they believe that Jesus Christ is their Lord and Savior, while other Mansions claim that Haile Selassie I is the true God. With his famous early reggae song The Israelites Desmond Dekker immortalised the Rastafari concept of themselves as the Lost Children of Israel. However, sometimes peoples native to Africa are identified with descendants of Ham, whereas the Old Testament of the Bible states that Abraham is descended from Shem.

Bnai Israel

There is an ethnic-religious group in Pakistan and Afghanistan which refers to itself as the Bnai Israel, or House of Israel, or Beit Israel. This group is referred to in English as the Pashtuns. Some Pashtuns claim to be the patriarchal historical descendants of the "ten lost tribes" of the northern Kingdom of Israel which were taken into captivity by Assyria.

Certain groups of Jews in other parts of South Asia are sometimes referred to as Benai Israel.

Christian theology

Latter-day Saints

The Latter Day Saint movement (commonly termed Mormons), believe that through baptism and receiving the Gift of the Holy Ghost, they become "regathered" as Israelites, either as recovered from the scattered tribes of Israel, or as Gentiles adopted and grafted into Israel, and thus becoming part of the chosen people of God[18]. These religious denominations derive from a movement started by Joseph Smith, Jr., and almost half of all members live in the United States; the movement does not strictly believe that they are ethnic Jews as such, but rather that Israelites can refer to many different cultures, on occasion including Jews[19]. They believe that certain Old Testament passages[20] are prophecies implying that the tribe of Joseph (Ephraim and Manasseh) will take a prominent role in the spread of the gospel to all of scattered Israelites in the last days, and that the tribe of Judah (ie. Judah) also has a prominent role in the last days and during the Millennium[21].

Christian Identity

The Christian Identity movement comprises a number of groups with a racialized theology which claim to be the only true Israelites on the basis that white Europeans are, in their belief, the literal descendants of the Israelites through the ten tribes, and who are accordingly still God's Chosen People. These groups generally deny that present-day Jews are descended from the Israelites nor Hebrews (who were in Egypt and were in the Exodus) but are instead descended from Turco-Mongolian blood, or Khazars, and of the Biblical Esau (who was also called Edom) who traded his birthright for a bowl of Beans.(Genesis 25:29–34)[3]

New Israel

Based on passages in the New Testament, some Christians believe that Christians are the "new Israel" that replaced the "Children of Israel" since the Jews rejected Jesus. This view is called Supersessionism. Many European settlers in the New World saw themselves as the heirs of those ancient tribes, hence one finds that they named their children and many towns they settled in with names connected to the figures in the Bible.

On the other hand, other Christians believe that the Jews are still the original children of Israel, and that Christians are adopted children of God but are not the new Israel. This view is a part of dispensationalist theology.

Islamic theology

In the Qur'an there are forty-three specific references to "Banū IsrāTemplate:ArabDINīl", meaning the "Children of Israel".[22] This is the Islamic term for the Israelites. There is a Surah (chapter) in the Qur'an titled "Bani Israel" (Arabic: بني اسرائيل, "The Children of Israel"), alternatively known as "Al-Isra" (Arabic: سورة الإسراء, "The Night Journey"). This Surah was revealed in the last year before Hijrah and takes its name from surah 17:4.[23]. Also starting from verse 40 in Surah Al-Baqara (سورة البقرة "The Cow") is the story of "Bani Israel".

In the Qur'an, there is a verse with Moses addressing his followers as "Muslims" (مُّسۡلِمِينَ Muslimïn[24]) or, grammatically translated in English, "those who submit [to God]".[25][26][27]

See also

- Archaeology of Israel

- Biblical archeology

- The Bible and history

- Who is a Jew?

- Groups claiming an affiliation with the ancient Israelites

- Shavei Israel

- Kingdom of Israel

- Kingdom of Judah

- Noahides

- History of ancient Israel and Judah

- House of Israel (Ghana)

- Gentile

- British Israelism

- Bible and The Bible and history.

- Israelis

- Anusim

- Half Jewish

- Tribal allotments of Israel

References and notes

- ^ entry in thefreedictionary.com

- ^ http://www.biu.ac.il/JH/Parasha/eng/bamidbar/coh.html "How Fair Are Your Tents, O Jacob", Dr. Gabriel H. Cohen, Bar-Ilan University

- ^ Numbers 10:12-28

- ^ Butler, Trent C. Editor, Holman Bible Dictionary, Broadman & Holman, 1991, entry Kenizzite

- ^ https://www3.nationalgeographic.com/genographic/atlas.html; Semino, et al, “Origin, Diffusion, and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups E and J: Inferences on the Neolithization of Europe and Later Migratory Events in the Mediterranean Area.” Am J Hum Genet. 2004 May; 74(5).

- ^ Ekins, JE (2005). "An Updated World-Wide Characterization of the Cohen Modal Haplotype" (PDF). ASHG meeting October 2005.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kleiman, Yaakov (2000-01-13). "The fascinating story of how DNA studies confirm an ancient biblical tradition". aish.com. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- ^ Y Chromosomes Traveling South: The Cohen Modal Haplotype and the Origins of the Lemba—the “Black Jews of Southern Africa”, retrieved 2008-06-15

- ^ Behar, DM; Thomas MG, Skorecki K, Hammer MF, Bulygina E, Rosengarten D, Jones AL, Held K, Moses V, Goldstein D, Bradman N, Weale ME (2003). "Multiple Origins of Ashkenazi Levites: Y Chromosome Evidence for Both Near Eastern and European Ancestries". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 73: 768–779.

- ^ An Updated World-Wide Characterization of the Cohen Modal Haplotype, Sorenson Molecular Genealogy Foundation (SMGF), Salt Lake City, UT, USA; [1]

- ^ Bunimovitz, Schlomo (2003). "The four room house: Embodying Iron Age israelite society". Near Eastern archaeology. 66 (1–2). Scholars Press, Atlanta, GA: 22–31.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rainey, Anson (2008-11). "Inside Outside: where did the early Israelites come from?". Biblical Archeology Review. 34 (6). Biblical Archeology Society: 45–50.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Elizabeth Bloch-Smith and Beth Alpert Nakhai, "A Landscape Comes to Life: The Iron Age I", Near Eastern Archaeology, Vol. 62, No. 2 (Jun., 1999), pp. 62-92

- ^ Abercrombie, John R. "Material Culture of the Ancient Canaanites, Israelites and Related Peoples: An Information DataBase from Excavations". Boston University. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ^ As of 2006

- ^ Tacitus: History: Book 5

- ^ Article Twelve Tribes on website Words of Wisdom [2]

- ^ Guide to LDS scriptural references on Israel

- ^ ibid

- ^ Isaiah 2:2-4, 11:10-13

- ^ ibid

- ^ Yahud, Encyclopedia of Islam

- ^ See Bani Israel (Quran sura)

- ^ Sura 10:84 (Arabic), Quran Explorer

- ^ See the article Muslim for definition and characteristics of Muslims.

- ^ Sura 10:84, University of Southern California.

- ^ Sura 10:84, Quran Explorer