Keynesian economics

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2015) |

Keynesian economics (/ˈkeɪnziən/ KAYN-zee-ən; or Keynesianism) are the various theories about how in the short run, and especially during recessions, economic output is strongly influenced by aggregate demand (total spending in the economy). In the Keynesian view, aggregate demand does not necessarily equal the productive capacity of the economy; instead, it is influenced by a host of factors and sometimes behaves erratically, affecting production, employment, and inflation.[1][2]

The theories forming the basis of Keynesian economics were first presented by the British economist John Maynard Keynes during the Great Depression in his 1936 book, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. Keynes contrasted his approach to the aggregate supply-focused classical economics that preceded his book. The interpretations of Keynes that followed are contentious and several schools of economic thought claim his legacy.

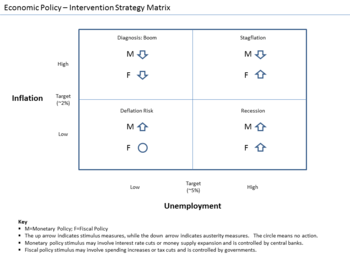

Keynesian economists often argue that private sector decisions sometimes lead to inefficient macroeconomic outcomes which require active policy responses by the public sector, in particular, monetary policy actions by the central bank and fiscal policy actions by the government, in order to stabilize output over the business cycle.[3] Keynesian economics advocates a mixed economy – predominantly private sector, but with a role for government intervention during recessions.

Keynesian economics served as the standard economic model in the developed nations during the later part of the Great Depression, World War II, and the post-war economic expansion (1945–1973), though it lost some influence following the oil shock and resulting stagflation of the 1970s.[4] The advent of the financial crisis of 2007–08 caused a resurgence in Keynesian thought,[5] which continues as new Keynesian economics.

Historical context

This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (October 2015) |

Prior to the publication of Keynes's General Theory, mainstream economic thought held that a state of general equilibrium existed in the economy: because the needs of consumers are always greater than the capacity of the producers to satisfy those needs, everything that is produced will eventually be consumed once the appropriate price is found for it. This perception is reflected in Say's law[6] and in the writing of David Ricardo,[7] which state that individuals produce so that they can either consume what they have manufactured or sell their output so that they can buy someone else's output. This argument rests upon the assumption that if a surplus of goods or services exists, they would naturally drop in price to the point where they would be consumed.

Keynes's theory overturned the mainstream thought of the time and brought about a greater awareness of structural inadequacies: problems such as unemployment, for example, are not viewed as a result of moral deficiencies like laziness, but rather result from imbalances in demand and whether the economy was expanding or contracting. Keynes argued that because there was no guarantee that the goods that individuals produce would be met with demand, unemployment was a natural consequence especially in the instance of an economy undergoing contraction.

He saw the economy as unable to maintain itself at full employment and believed that it was necessary for the government to step in and put under-utilized savings to work through government spending. Thus, according to Keynesian theory, some individually rational microeconomic-level actions such as not investing savings in the goods and services produced by the economy, if taken collectively by a large proportion of individuals and firms, can lead to outcomes wherein the economy operates below its potential output and growth rate.

Prior to Keynes, a situation in which aggregate demand for goods and services did not meet supply was referred to by classical economists as a general glut, although there was disagreement among them as to whether a general glut was possible. Keynes argued that when a glut occurred, it was the over-reaction of producers and the laying off of workers that led to a fall in demand and perpetuated the problem. Keynesians therefore advocate an active stabilization policy to reduce the amplitude of the business cycle, which they rank among the most serious of economic problems. According to the theory, government spending can be used to increase aggregate demand, thus increasing economic activity, reducing unemployment and deflation.

Theory

This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (October 2015) |

Keynes argued that the solution to the Great Depression was to stimulate the country ("inducement to invest") through some combination of two approaches:

- A reduction in interest rates (monetary policy), and

- Government investment in infrastructure (fiscal policy).

If the interest rate at which businesses and consumers can borrow is decreased, investments which were previously uneconomic become profitable, and large consumer sales which are normally financed through debt (such as houses, automobiles, and, historically, even appliances like refrigerators) become more affordable. A principle function of central banks in countries which have them is to influence this interest rate through a variety of mechanisms which are collectively called monetary policy. This is how monetary policy which reduces interest rates is thought to stimulate economic activity, i.e. "grow the economy," and why it is called expansionary monetary policy.

Expansionary fiscal policy consists of increasing net public spending, which the government can effect by a) taxing less, b) spending more, or c) both. Investment and consumption by government raises demand for businesses' products and for employment, reversing the effects of the aforementioned imbalance.[1] If desired spending exceeds revenue, the government finances the difference by borrowing from capital markets by issuing government bonds. This is called deficit spending. Two points are important to note at this point. First, deficits are not required for expansionary monetary policy, and second, it is only change in net spending that can stimulate or depress the economy. For example, if a government ran a deficit of 10% both last year and this year, this would represent neutral fiscal policy. In fact, if it ran a deficit of 10% last year and 5% this year, this would actually be contractionary. On the other hand, if the government ran a surplus of 10% of GDP last year and 5% this year, that would be expansionary fiscal policy, despite never running a deficit at all.

In the price mechanism of neoclassical economics, it is predicted that, in a competitive market, if demand for a particular good or service falls, that would immediately cause the price for that good or service to fall, which in turn would decrease supply and increase demand, thereby bringing them back to equilibrium. A central conclusion of Keynesian economics, in strong contrast to the previously dominant models of neoclassical synthesis, is that there are some situations in which a depressed economy would not quickly self-correct towards full employment and potential output, but could remain trapped indefinitely with both high unemployment and mothballed factories. To the observation that these were, in fact, the prevailing conditions throughout the industrialized world for many years during the Great Depression, classical models could only conclude that it was a temporary aberration. The purpose of Keynes' theory was to show such conditions could, without intervention, persist in a stable, though dismal, equilibrium.

By the end of the Second World War, Keynesianism was the most popular school of economic theory in the non-Communist world. Beginning in the late 1960s, a new classical macroeconomics movement arose, critical of Keynesian assumptions (see sticky prices), and seemed, especially in the 1970s, to explain certain phenomena (e.g. the co-existence of high unemployment and high inflation, or "stagflation") better. It was characterized by explicit and rigorous adherence to microfoundations, as well as use of increasingly sophisticated mathematical modelling. However, by the late 1980s, certain failures of the new classical models, both theoretical (see Real business cycle theory) and empirical (see the "Volcker recession")[8] hastened the emergence of New Keynesian economics, a school which sought to unite the most realistic aspects of Keynesian and neo-classical assumptions and place them on more rigorous theoretical foundation than ever before.

Interpretations of Keynes have emphasized his stress on the international coordination of Keynesian policies, the need for international economic institutions, and the ways in which economic forces could lead to war or could promote peace.[9]

Concept

Wages and spending

During the Great Depression, the classical theory attributed mass unemployment to high and rigid real wages.[citation needed]

To Keynes, the determination of wages was more complicated. First, he argued that it is not real but nominal wages that are set in negotiations between employers and workers, as opposed to a barter relationship. Second, nominal wage cuts would be difficult to put into effect because of laws and wage contracts. Even classical economists admitted that these exist; unlike Keynes, they advocated abolishing minimum wages, unions, and long-term contracts, increasing labour market flexibility. However, to Keynes, people will resist nominal wage reductions, even without unions, until they see other wages falling and a general fall of prices.

Keynes rejected the idea that cutting wages would cure recessions. He examined the explanations for this idea and found them all faulty. He also considered the most likely consequences of cutting wages in recessions, under various different circumstances. He concluded that such wage cutting would be more likely to make recessions worse rather than better.[10]

Further, if wages and prices were falling, people would start to expect them to fall. This could make the economy spiral downward as those who had money would simply wait as falling prices made it more valuable – rather than spending. As Irving Fisher argued in 1933, in his Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions, deflation (falling prices) can make a depression deeper as falling prices and wages made pre-existing nominal debts more valuable in real terms.

Excessive saving

To Keynes, excessive saving, i.e. saving beyond planned investment, was a serious problem, encouraging recession or even depression. Excessive saving results if investment falls, perhaps due to falling consumer demand, over-investment in earlier years, or pessimistic business expectations, and if saving does not immediately fall in step, the economy would decline.

The classical economists argued that interest rates would fall due to an increase in savings. The first diagram, adapted from the only graph in The General Theory, shows this process. (For simplicity, other sources of the demand for or supply of savings are ignored here.) Assume that fixed investment in capital goods falls from "old I" to "new I" (step a). Second (step b), the resulting excess of saving causes interest-rate cuts, abolishing the excess supply: so again we have saving (S) equal to investment. The interest-rate (i) fall prevents that of production and employment.

Keynes had a complex argument against this laissez-faire response. The graph below summarizes his argument, assuming again that fixed investment falls (step A). First, saving does not fall much as interest rates fall, since the income and substitution effects of falling rates go in conflicting directions. Second, since planned fixed investment in plant and equipment is based mostly on long-term expectations of future profitability, that spending does not rise much as interest rates fall.

So S and I are drawn as steep (inelastic) in the graph. Given the inelasticity of both demand and supply, a large interest-rate fall is needed to close the saving/investment gap. As drawn, this requires a negative interest rate at equilibrium (where the new I line would intersect the old S line). However, this negative interest rate is not necessary to Keynes's argument.

Third, Keynes argued that saving and investment are not the main determinants of interest rates, especially in the short run. Instead, the supply of and the demand for the stock of money determine interest rates in the short run. (This is not drawn in the graph.) Neither changes quickly in response to excessive saving to allow fast interest-rate adjustment.

Finally, Keynes suggested that, because of fear of capital losses on assets besides money, there may be a "liquidity trap" setting a floor under which interest rates cannot fall. While in this trap, interest rates are so low that any increase in money supply will cause bond-holders (fearing rises in interest rates and hence capital losses on their bonds) to sell their bonds to attain money (liquidity).

In the diagram, the equilibrium suggested by the new I line and the old S line cannot be reached, so that excess saving persists. Some (such as Paul Krugman) see this latter kind of liquidity trap as prevailing in Japan in the 1990s. Most economists agree that nominal interest rates cannot fall below zero. However, some economists (particularly those from the Chicago school) reject the existence of a liquidity trap.

Even if the liquidity trap does not exist, there is a fourth (perhaps most important) element to Keynes's critique. Saving involves not spending all of one's income. Thus, it means insufficient demand for business output, unless it is balanced by other sources of demand, such as fixed investment. Therefore, excessive saving corresponds to an unwanted accumulation of inventories, or what classical economists called a general glut.[11]

This pile-up of unsold goods and materials encourages businesses to decrease both production and employment. This in turn lowers people's incomes – and saving, causing a leftward shift in the S line in the diagram (step B). For Keynes, the fall in income did most of the job by ending excessive saving and allowing the loanable funds market to attain equilibrium. Instead of interest-rate adjustment solving the problem, a recession does so. Thus in the diagram, the interest-rate change is small.

Whereas the classical economists assumed that the level of output and income was constant and given at any one time (except for short-lived deviations), Keynes saw this as the key variable that adjusted to equate saving and investment.

Finally, a recession undermines the business incentive to engage in fixed investment. With falling incomes and demand for products, the desired demand for factories and equipment (not to mention housing) will fall. This accelerator effect would shift the I line to the left again, a change not shown in the diagram above. This recreates the problem of excessive saving and encourages the recession to continue.

In sum, to Keynes there is interaction between excess supplies in different markets, as unemployment in labour markets encourages excessive saving – and vice versa. Rather than prices adjusting to attain equilibrium, the main story is one of quantity adjustment allowing recessions and possible attainment of underemployment equilibrium.

Active fiscal policy

Classical economists have traditionally advocated balanced government budgets. Keynesians, on the other hand, believe that it is entirely legitimate and appropriate for governments to incur expenditure in excess of taxation revenues during periods of economic stagnation such as the Great Depression, which dominated economic life at the time he was developing and publicizing his theories.[12]

Contrary to some critical characterizations of it, Keynesianism does not consist solely of deficit spending. Keynesianism recommends counter-cyclical policies.[13] An example of a counter-cyclical policy is raising taxes to cool the economy and to prevent inflation when there is abundant demand-side growth, and engaging in deficit spending on labour-intensive infrastructure projects to stimulate employment and stabilize wages during economic downturns. Classical economics, on the other hand, argues that one should cut taxes when there are budget surpluses, and cut spending – or, less likely, increase taxes – during economic downturns.

Keynes's ideas influenced Franklin D. Roosevelt's view that insufficient buying-power caused the Depression. During his presidency, Roosevelt adopted some aspects of Keynesian economics, especially after 1937, when, in the depths of the Depression, the United States suffered from recession yet again following fiscal contraction. But to many the true success of Keynesian policy can be seen at the onset of World War II, which provided a kick to the world economy, removed uncertainty, and forced the rebuilding of destroyed capital. Keynesian ideas became almost official in social-democratic Europe after the war and in the U.S. in the 1960s.

Keynes developed a theory which suggested that active government policy could be effective in managing the economy. Rather than seeing unbalanced government budgets as wrong, Keynes advocated what has been called countercyclical fiscal policies, that is, policies that acted against the tide of the business cycle: deficit spending when a nation's economy suffers from recession or when recovery is long-delayed and unemployment is persistently high – and the suppression of inflation in boom times by either increasing taxes or cutting back on government outlays. He argued that governments should solve problems in the short run rather than waiting for market forces to do it in the long run, because, "in the long run, we are all dead."[14]

This contrasted with the classical and neoclassical economic analysis of fiscal policy. Fiscal stimulus could actuate production. But, to these schools, there was no reason to believe that this stimulation would outrun the side-effects that "crowd out" private investment: first, it would increase the demand for labour and raise wages, hurting profitability; Second, a government deficit increases the stock of government bonds, reducing their market price and encouraging high interest rates, making it more expensive for business to finance fixed investment. Thus, efforts to stimulate the economy would be self-defeating.

The Keynesian response is that such fiscal policy is appropriate only when unemployment is persistently high, above the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU). In that case, crowding out is minimal. Further, private investment can be "crowded in": Fiscal stimulus raises the market for business output, raising cash flow and profitability, spurring business optimism. To Keynes, this accelerator effect meant that government and business could be complements rather than substitutes in this situation.

Second, as the stimulus occurs, gross domestic product rises, raising the amount of saving, helping to finance the increase in fixed investment. Finally, government outlays need not always be wasteful: government investment in public goods that will not be provided by profit-seekers will encourage the private sector's growth. That is, government spending on such things as basic research, public health, education, and infrastructure could help the long-term growth of potential output.

In Keynes's theory, there must be significant slack in the labour market before fiscal expansion is justified.

Keynesian economists believe that adding to profits and incomes during boom cycles through tax cuts, and removing income and profits from the economy through cuts in spending during downturns, tends to exacerbate the negative effects of the business cycle. This effect is especially pronounced when the government controls a large fraction of the economy, as increased tax revenue may aid investment in state enterprises in downturns, and decreased state revenue and investment harm those enterprises.

"Multiplier effect" and interest rates

Two aspects of Keynes's model have implications for policy:

First, there is the "Keynesian multiplier", first developed by Richard F. Kahn in 1931. Exogenous increases in spending, such as an increase in government outlays, increases total spending by a multiple of that increase. A government could stimulate a great deal of new production with a modest outlay if:

- The people who receive this money then spend most on consumption goods and save the rest.

- This extra spending allows businesses to hire more people and pay them, which in turn allows a further increase in consumer spending.

This process continues. At each step, the increase in spending is smaller than in the previous step, so that the multiplier process tapers off and allows the attainment of an equilibrium. This story is modified and moderated if we move beyond a "closed economy" and bring in the role of taxation: The rise in imports and tax payments at each step reduces the amount of induced consumer spending and the size of the multiplier effect.

Second, Keynes re-analyzed the effect of the interest rate on investment. In the classical model, the supply of funds (saving) determines the amount of fixed business investment. That is, under the classical model, since all savings are placed in banks, and all business investors in need of borrowed funds go to banks, the amount of savings determines the amount that is available to invest. Under Keynes's model, the amount of investment is determined independently by long-term profit expectations and, to a lesser extent, the interest rate. The latter opens the possibility of regulating the economy through money supply changes, via monetary policy. Under conditions such as the Great Depression, Keynes argued that this approach would be relatively ineffective compared to fiscal policy. But, during more "normal" times, monetary expansion can stimulate the economy.[citation needed]

IS–LM model

The IS–LM model is nearly as influential as Keynes's original analysis in determining actual policy and economics education. It relates aggregate demand and employment to three exogenous quantities, i.e., the amount of money in circulation, the government budget, and the state of business expectations. This model was very popular with economists after World War II because it could be understood in terms of general equilibrium theory. This encouraged a much more static vision of macroeconomics than that described above.[citation needed]

History

Precursors

Keynes's work was part of a long-running debate within economics over the existence and nature of general gluts. While a number of the policies Keynes advocated (the notable one being government deficit spending at times of low private investment or consumption) and the theoretical ideas he proposed (effective demand, the multiplier, the paradox of thrift) were advanced by various authors in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Keynes's unique contribution was to provide a general theory of these, which proved acceptable to the political and economic establishments.

Schools

An intellectual precursor of Keynesian economics was underconsumption theory in classical economics, dating from such 19th-century economists as Thomas Malthus, the Birmingham School of Thomas Attwood,[15] and the American economists William Trufant Foster and Waddill Catchings, who were influential in the 1920s and 1930s. Underconsumptionists were, like Keynes after them, concerned with failure of aggregate demand to attain potential output, calling this "underconsumption" (focusing on the demand side), rather than "overproduction" (which would focus on the supply side), and advocating economic interventionism. Keynes specifically discussed underconsumption (which he wrote "under-consumption") in the General Theory, in Chapter 22, Section IV and Chapter 23, Section VII.

Numerous concepts were developed earlier and independently of Keynes by the Stockholm school during the 1930s; these accomplishments were described in a 1937 article, published in response to the 1936 General Theory, sharing the Swedish discoveries.[16]

Concepts

The multiplier dates to work in the 1890s by the Australian economist Alfred de Lissa, the Danish economist Julius Wulff, and the German-American economist Nicholas Johannsen,[17] the latter being cited in a footnote of Keynes.[18] Nicholas Johannsen also proposed a theory of effective demand in the 1890s.

The paradox of thrift was stated in 1892 by John M. Robertson in his The Fallacy of Saving, in earlier forms by mercantilist economists since the 16th century, and similar sentiments date to antiquity.[19][20]

Today these ideas, regardless of provenance, are referred to in academia under the rubric of "Keynesian economics", due to Keynes's role in consolidating, elaborating, and popularizing them.

Keynes and the classics

Keynes sought to distinguish his theories from and oppose them to "classical economics," by which he meant the economic theories of David Ricardo and his followers, including John Stuart Mill, Alfred Marshall, Francis Ysidro Edgeworth, and Arthur Cecil Pigou. A central tenet of the classical view, known as Say's law, states that "supply creates its own demand". Say's Law can be interpreted in two ways. First, the claim that the total value of output is equal to the sum of income earned in production is a result of a national income accounting identity, and is therefore indisputable. A second and stronger claim, however, that the "costs of output are always covered in the aggregate by the sale-proceeds resulting from demand" depends on how consumption and saving are linked to production and investment. In particular, Keynes argued that the second, strong form of Say's Law only holds if increases in individual savings exactly match an increase in aggregate investment.[21]

Keynes sought to develop a theory that would explain determinants of saving, consumption, investment and production. In that theory, the interaction of aggregate demand and aggregate supply determines the level of output and employment in the economy.

Because of what he considered the failure of the "Classical Theory" in the 1930s, Keynes firmly objects to its main theory – adjustments in prices would automatically make demand tend to the full employment level.

Neo-classical theory supports that the two main costs that shift demand and supply are labour and money. Through the distribution of the monetary policy, demand and supply can be adjusted. If there were more labour than demand for it, wages would fall until hiring began again. If there were too much saving, and not enough consumption, then interest rates would fall until people either cut their savings rate or started borrowing.

Postwar Keynesianism

Keynes's ideas became widely accepted after World War II, and until the early 1970s, Keynesian economics provided the main inspiration for economic policy makers in Western industrialized countries.[4] Governments prepared high quality economic statistics on an ongoing basis and tried to base their policies on the Keynesian theory that had become the norm. In the early era of social liberalism and social democracy, most western capitalist countries enjoyed low, stable unemployment and modest inflation, an era called the Golden Age of Capitalism.

In terms of policy, the twin tools of post-war Keynesian economics were fiscal policy and monetary policy. While these are credited to Keynes, others, such as economic historian David Colander, argue that they are, rather, due to the interpretation of Keynes by Abba Lerner in his theory of functional finance, and should instead be called "Lernerian" rather than "Keynesian".[22]

Through the 1950s, moderate degrees of government demand leading industrial development, and use of fiscal and monetary counter-cyclical policies continued, and reached a peak in the "go go" 1960s, where it seemed to many Keynesians that prosperity was now permanent. In 1971, Republican US President Richard Nixon even proclaimed "I am now a Keynesian in economics."[23]

However, with the oil shock of 1973, and the economic problems of the 1970s, Keynesian economics began to fall out of favour. During this time, many economies experienced high and rising unemployment, coupled with high and rising inflation, contradicting the Phillips curve's prediction. This stagflation meant that the simultaneous application of expansionary (anti-recession) and contractionary (anti-inflation) policies appeared to be necessary. This dilemma led to the end of the Keynesian near-consensus of the 1960s, and the rise throughout the 1970s of ideas based upon more classical analysis, including monetarism, supply-side economics,[23] and new classical economics.

At the same time, Keynesians began during the period to reorganize their thinking (some becoming associated with New Keynesian economics). One strategy, utilized also as a critique of the notably high unemployment and potentially disappointing GNP growth rates associated with the latter two theories by the mid-1980s, was to emphasize low unemployment and maximal economic growth at the cost of somewhat higher inflation (its consequences kept in check by indexing and other methods, and its overall rate kept lower and steadier by such potential policies as Martin Weitzman's share economy).[24]

Multiple schools of economic thought that trace their legacy to Keynes currently exist, the notable ones being Neo-Keynesian economics, New Keynesian economics, and Post-Keynesian economics. Keynes's biographer Robert Skidelsky writes that the post-Keynesian school has remained closest to the spirit of Keynes's work in following his monetary theory and rejecting the neutrality of money.[25][26]

In the postwar era, Keynesian analysis was combined with neoclassical economics to produce what is generally termed the "neoclassical synthesis", yielding Neo-Keynesian economics, which dominated mainstream macroeconomic thought. Though it was widely held that there was no strong automatic tendency to full employment, many believed that if government policy were used to ensure it, the economy would behave as neoclassical theory predicted. This post-war domination by Neo-Keynesian economics was broken during the stagflation of the 1970s. There was a lack of consensus among macroeconomists in the 1980s. However, the advent of New Keynesian economics in the 1990s, modified and provided microeconomic foundations for the neo-Keynesian theories. These modified models now dominate mainstream economics.

Post-Keynesian economists, on the other hand, reject the neoclassical synthesis and, in general, neoclassical economics applied to the macroeconomy. Post-Keynesian economics is a heterodox school that holds that both Neo-Keynesian economics and New Keynesian economics are incorrect, and a misinterpretation of Keynes's ideas. The Post-Keynesian school encompasses a variety of perspectives, but has been far less influential than the other more mainstream Keynesian schools.

Other schools of economics

The Keynesian schools of economics are situated alongside a number of other schools that have the same perspectives on what the economic issues are, but differ on what causes them and how to best resolve them:

Stockholm School

The Stockholm school rose to prominence at about the same time that Keynes published his General Theory and shared a common concern in business cycles and unemployment. The second generation of Swedish economists also advocated government intervention through spending during economic downturns[27] although opinions are divided over whether they conceived the essence of Keynes's theory before he did.[28]

Monetarism

There was debate between Monetarists and Keynesians in the 1960s over the role of government in stabilizing the economy. Both Monetarists and Keynesians are in agreement over the fact that issues such as business cycles, unemployment, and deflation are caused by inadequate demand. However, they had fundamentally different perspectives on the capacity of the economy to find its own equilibrium, and the degree of government intervention that would be appropriate. Keynesians emphasized the use of discretionary fiscal policy and monetary policy, while monetarists argued the primacy of monetary policy, and that it should be rules-based.[29]

The debate was largely resolved in the 1980s. Since then, economists have largely agreed that central banks should bear the primary responsibility for stabilizing the economy, and that monetary policy should largely follow the Taylor rule – which many economists credit with the Great Moderation.[30][31] The financial crisis of 2007–08, however, has convinced many economists and governments of the need for fiscal interventions and highlighted the difficulty in stimulating economies through monetary policy alone during a liquidity trap.[32]

Public choice theory

Some Marxist economists criticized Keynesian economics.[33] For example, in his 1946 appraisal[34] Paul Sweezy, while admitting that there was much in the General Theory's analysis of effective demand which Marxists could draw upon, described Keynes as in the last resort a prisoner of his neoclassical upbringing. Sweezy argued Keynes had never been able to view the capitalist system as a totality. He argued Keynes had regarded the class struggle carelessly, and overlooked the class role of the capitalist state, which he treated as a deus ex machina, and some other points. While Michał Kalecki was generally enthusiastic about the Keynesian revolution, he predicted that it would not endure, in his article "Political Aspects of Full Employment". In the article Kalecki predicted that the full employment delivered by Keynesian policy would eventually lead to a more assertive working class and weakening of the social position of business leaders, causing the elite to use their political power to force the displacement of the Keynesian policy even though profits would be higher than under a laissez faire system: The erosion of social prestige and political power would be unacceptable to the elites despite higher profits.[35]

James M. Buchanan[36] criticized Keynesian economics on the grounds that governments would in practice be unlikely to implement theoretically optimal policies. The implicit assumption underlying the Keynesian fiscal revolution, according to Buchanan, was that economic policy would be made by wise men, acting without regard to political pressures or opportunities, and guided by disinterested economic technocrats. He argued that this was an unrealistic assumption about political, bureaucratic and electoral behaviour. Buchanan blamed Keynesian economics for what he considered a decline in America's fiscal discipline.[37] Buchanan argued that deficit spending would evolve into a permanent disconnect between spending and revenue, precisely because it brings short-term gains, so, ending up institutionalizing irresponsibility in the federal government, the largest and most central institution in our society.[38] Martin Feldstein argues that the legacy of Keynesian economics–the misdiagnosis of unemployment, the fear of saving, and the unjustified government intervention–affected the fundamental ideas of policy makers.[39] Milton Friedman thought that Keynes's political bequest was harmful for two reasons. First, he thought whatever the economic analysis, benevolent dictatorship is likely sooner or later to lead to a totalitarian society. Second, he thought Keynes's economic theories appealed to a group far broader than economists primarily because of their link to his political approach.[40] Alex Tabarrok argues that Keynesian politics–as distinct from Keynesian policies–has failed pretty much whenever it's been tried, at least in liberal democracies.[41]

In response to this argument, John Quiggin,[42] wrote about these theories' implication for a liberal democratic order. He thought if it is generally accepted that democratic politics is nothing more than a battleground for competing interest groups, then reality will come to resemble the model. Paul Krugman wrote "I don’t think we need to take that as an immutable fact of life; but still, what are the alternatives?" [43] Daniel Kuehn, criticized James M. Buchanan. He argued, "if you have a problem with politicians - criticize politicians," not Keynes.[44] He also argued that empirical evidence makes it pretty clear that Buchanan was wrong.[45][46] James Tobin argued, if advising government officials, politicians, voters, it's not for economists to play games with them.[47] Keynes implicitly rejected this argument, in "soon or late it is ideas not vested interests which are dangerous for good or evil."[48][49]

Brad DeLong has argued that politics is the main motivator behind objections to the view that government should try to serve a stabilizing macroeconomic role.[50] Paul Krugman argued that in conjunction with theory from America's first Nobel Prize winning economist, Paul Samuelson, he continues to employ Keynesian economics, so as to avoid intellectual instability, political instability, and financial instability.[51]

New Classical

Another influential school of thought was based on the Lucas critique of Keynesian economics. This called for greater consistency with microeconomic theory and rationality, and in particular emphasized the idea of rational expectations. Lucas and others argued that Keynesian economics required remarkably foolish and short-sighted behaviour from people, which totally contradicted the economic understanding of their behaviour at a micro level. New classical economics introduced a set of macroeconomic theories that were based on optimizing microeconomic behaviour. These models have been developed into the real business-cycle theory, which argues that business cycle fluctuations can to a large extent be accounted for by real (in contrast to nominal) shocks.

Beginning in the late 1950s new classical macroeconomists began to disagree with the methodology employed by Keynes and his successors. Keynesians emphasized the dependence of consumption on disposable income and, also, of investment on current profits and current cash flow. In addition, Keynesians posited a Phillips curve that tied nominal wage inflation to unemployment rate. To support these theories, Keynesians typically traced the logical foundations of their model (using introspection) and supported their assumptions with statistical evidence.[52] New classical theorists demanded that macroeconomics be grounded on the same foundations as microeconomic theory, profit-maximizing firms and rational, utility-maximizing consumers.[52]

The result of this shift in methodology produced several important divergences from Keynesian Macroeconomics:[52]

- Independence of Consumption and current Income (life-cycle permanent income hypothesis)

- Irrelevance of Current Profits to Investment (Modigliani–Miller theorem)

- Long run independence of inflation and unemployment (natural rate of unemployment)

- The inability of monetary policy to stabilize output (rational expectations)

- Irrelevance of Taxes and Budget Deficits to Consumption (Ricardian equivalence)

See also

References

- ^ a b Blinder, Alan S. (2008). "Keynesian Economics". In David R. Henderson (ed.) (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0865976658. OCLC 237794267.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ IMF Back to Basics: What Is Keynesian Economics?

- ^ Sullivan, Arthur; Steven M. Sheffrin (2003). Economics: Principles in action. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-063085-3.

- ^ a b Fletcher, Gordon (1989). The Keynesian Revolution and Its Critics: Issues of Theory and Policy for the Monetary Production Economy. Palgrave MacMillan. pp. xix–xxi, 88, 189–191, 234–238, 256–261. ISBN 0-312-45260-8.

- ^ "Economic Crisis Mounts in Germany". Der Spiegel. 4 November 2008. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ Say, Jean-Baptiste (2001). A Treatise on Political Economy; or the Production Distribution and Consumption of Wealth. Kitchener: Batoche Books.

- ^ Ricardo, David (1871). On The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation.

- ^ Krugman, Paul. "Trash Talk and the Macroeconomic Divide". Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ Markwell, Donald (2006). John Maynard Keynes and International Relations: Economic Paths to War and Peace. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-829236-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Keynes, John Maynard (2008). The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. Chapter 19: BN Publishing. ISBN 9650060251.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "The General Glut Controversy".

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Galbraith, John K. (2009) The Great Crash.Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 137

- ^ "I Think Keynes Mistitled His Book". The Washington Post. 26 July 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ Keynes, John Maynard (1924). "The Theory of Money and the Foreign Exchanges". A Tract on Monetary Reform.

- ^ Glasner, David (1997). "Attwood, Thomas (1783–1856)". In Glasner, David (ed.). Business Cycles and Depressions: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 22. ISBN 0-8240-0944-4. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Ohlin, Bertil (1937). "Some Notes on the Stockholm Theory of Savings and Investment". Economic Journal.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Dimand, Robert William (1988). The origins of the Keynesian revolution. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 117. ISBN 0-8047-1525-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Keynes, John Maynard (1930). "Treatise on Money". Nature. 127 (3216). London: Macmillan: 90. Bibcode:1931Natur.127..919M. doi:10.1038/127919a0.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Nash, Robert T.; Gramm, William P. (1969). "A Neglected Early Statement the Paradox of Thrift". History of Political Economy. 1 (2): 395–400. doi:10.1215/00182702-1-2-395.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Robertson, John M. (1892). The Fallacy of Saving.

- ^ cf. General Theory, Ch.1,2

- ^ "What eventually became known as textbook Keynesian policies were in many ways Lerner's interpretations of Keynes's policies, especially those expounded in The Economics of Control (1944) and later in The Economics of Employment (1951). ... Textbook expositions of Keynesian policy naturally gravitated to the black and white 'Lernerian' policy of Functional Finance rather than the grayer Keynesian policies. Thus, the vision that monetary and fiscal policy should be used as a balance wheel, which forms a key element in the textbook policy revolution, deserves to be called Lernerian rather than Keynesian." (Colander 1984, p. 1573)

- ^ a b Lewis, Paul (15 August 1976). "Nixon's Economic Policies Return to Haunt the G.O.P." New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Blinder, Alan S. (1987). Hard Heads, Soft Hearts: Tough Minded Economics for a Just Society. New York: Perseus Books. pp. 65–66. ISBN 0-201-14519-7.

- ^ Skidelsky 2009

- ^ Financial markets, money and the real world, by Paul Davidson, pp. 88–89

- ^ Jonung, Lars (1991). The Stockholm School of Economics Revisited. Cambridge University Press. p. 5.

- ^ Jonung, Lars (1991). The Stockholm School of Economics Revisited. Cambridge University Press. p. 18.

- ^ Abel, Andrew; Ben Bernanke (2005). "14.3". Macroeconomics (5th ed.). Pearson Addison Weasley. pp. 543–557. ISBN 0-321-22333-0.

- ^ Bernanke, Ben (20 February 2004). "The Great Moderation". federalreserve.gov. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Monetary Policy, Output Composition and the Great Moderation, June 2007

- ^ Henry Farrell and John Quiggin (March 2012). "Consensus, Dissensus and Economic Ideas: The Rise and Fall of Keynesianism During the Economic Crisis" (pdf). The Center for the Study of Development Strategies. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ Michael Charles Howard, John Edward King. A History of Marxian Economics, Volume II: 1929-1990. Princeton Legacy library. pp. 91–108.

- ^ Sweezy, P. M. (1946). "John Maynard Keynes". Science and Society: 398–405.

- ^ Kalecki (1943). "Political Aspects of Full Employment". Monthly Review. The Political Quarterly. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Robert D. McFadden, James M. Buchanan, Economic Scholar and Nobel Laureate, Dies at 93, New York Times, January 9, 2013

- ^ Tyler Cowen, It's Time to Face the Fiscal Illusion, New York Times, March 5, 2011

- ^ Feldstein, Martin (Summer 1981). "The retreat from Keynesian economics". The Public Interest: 92–105.

- ^ Friedman, Milton (1997). "John Maynard Keynes". FRB Richmond Economic Quarterly. 83: 1–23.

- ^ "The Failure of Keynesian Politics" (2011)

- ^ John Quiggin, Public choice = Marxism

- ^ Paul Krugman, "Living Without Discretionary Fiscal Policy" (2011)

- ^ Daniel Kuehn, Democracy in Deficit: Hayek Edition,

- ^ Daniel Kuehn, Yes, a lot of people have a very odd view of the 1970s

- ^ Daniel Kuehn, The Significance of James Buchanan

- ^ Snowdon, Brian, Howard R. Vane (2005). Modern Macroeconomics: Its Origin, Development and Current State. p. 155.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Keynes, John Maynard (1936). The General Theory Of Employment, Interest And Money.

- ^ Peacock, Alan (1992). Public Choice Analysis in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 60.

- ^ J. Bradford DeLong, "The Retreat of Macroeconomic Policy", Project Syndicate, November 25, 2010

- ^ Paul Krugman, "The Instability of Moderation"

- ^ a b c Akerlof, George A. (2007). "The Missing Motivation in Macroeconomics". American Economic Review. 97 (1): 5–36. doi:10.1257/aer.97.1.5.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Keynes, John Maynard (31 December 1933). "An Open Letter to President Roosevelt". New York Times.

- Keynes, John Maynard (2007) [1936]. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-230-00476-8.

- Markwell, Donald, John Maynard Keynes and International Relations: Economic Paths to War and Peace, Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 9780198292364

- Markwell, Donald, Keynes and Australia, Reserve Bank of Australia, 2000. http://www.rba.gov.au/publications/rdp/2000/pdf/rdp2000-04.pdf

- Stein, Jerome L. (1982). Monetarist, Keynesian & New classical economics. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-12908-1.

- Gordon, Robert J. (1990). "What Is New-Keynesian Economics?". Journal of Economic Literature. 28 (3): 1115–1171. JSTOR 2727103.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Works by John Maynard Keynes at Project Gutenberg

- "We are all Keynesians now" – Historic article from Time magazine, 1965