Local anesthetic

Local anesthetic (LA) is a medication that causes reversible absence of pain sensation, although other senses are often affected as well. Also, when it is used on specific nerve pathways (local anesthetic nerve block), paralysis (loss of muscle power) can be achieved as well.

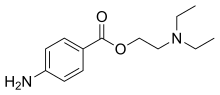

Clinical local anesthetics belong to one of two classes: aminoamide and aminoester local anesthetics. Synthetic local anesthetics are structurally related to cocaine. They differ from cocaine mainly in that they have a very low abuse potential and do not produce hypertension or (with few exceptions) vasoconstriction.

Local anesthetics are used in various techniques of local anesthesia such as:

- Topical anesthesia (surface)

- Topical administration of cream, gel, ointment, liquid, spray &c of anaesthetic dissolved in DMSO or other solvents/carriers for deeper absorption

- Infiltration

- Plexus block

- Epidural (extradural) block

- Spinal anesthesia (subarachnoid block)

- Iontophoresis

Medical uses

Acute pain

Acute pain may occur due to trauma, surgery, infection, disruption of blood circulation or many other conditions in which there is tissue injury. In a medical setting it is usually desirable to alleviate pain when its warning function is no longer needed. Besides improving patient comfort, pain therapy can also reduce harmful physiological consequences of untreated pain.

Acute pain can often be managed using analgesics. However, conduction anesthesia may be preferable because of superior pain control and fewer side effects. For purposes of pain therapy, local anesthetic drugs are often given by repeated injection or continuous infusion through a catheter. Low doses of local anesthetic drugs can be sufficient so that muscle weakness does not occur and patients may be mobilized.

Some typical uses of conduction anesthesia for acute pain are:

- Labor pain (epidural anesthesia, pudendal nerve blocks)

- Postoperative pain (peripheral nerve blocks, epidural anesthesia)

- Trauma (peripheral nerve blocks, intravenous regional anesthesia, epidural anesthesia)

Chronic pain

Chronic pain is a complex and often serious condition that requires diagnosis and treatment by an expert in pain medicine. Local anesthetics can be applied repeatedly or continuously for prolonged periods to relieve chronic pain, usually in combination with medication such as opioids, NSAIDs, and anticonvulsants.

Surgery

Virtually every part of the body can be anesthetized using conduction anesthesia. However, only a limited number of techniques are in common clinical use. Sometimes conduction anesthesia is combined with general anesthesia or sedation for the patient's comfort and ease of surgery. Typical operations performed under conduction anesthesia include:

- Dentistry (surface anesthesia, infiltration anesthesia or intraligamentary anesthesia during restorative operations or extractions, regional nerve blocks during extractions and surgeries.)

- Podiatry (Cutaneous, nail avulsions, matricectomy and various other podiatric procedures)

- Eye surgery (surface anesthesia with topical anesthetics, retrobulbar block)

- ENT operations, head and neck surgery (infiltration anesthesia, field blocks, peripheral nerve blocks, plexus anesthesia)

- Shoulder and arm surgery (plexus anesthesia, intravenous regional anesthesia)[1]

- Heart and lung surgery (epidural anesthesia combined with general anesthesia)

- Abdominal surgery (epidural/spinal anesthesia, often combined with general anesthesia)

- Gynecological, obstetrical and urological operations (spinal/epidural anesthesia)

- Bone and joint surgery of the pelvis, hip and leg (spinal/epidural anesthesia, peripheral nerve blocks, intravenous regional anesthesia)

- Surgery of skin and peripheral blood vessels (topical anesthesia, field blocks, peripheral nerve blocks, spinal/epidural anesthesia)

Other uses

Topical anesthesia, in the form of lidocaine/prilocaine (EMLA) is most commonly used to enable relatively painless venipuncture (blood collection) and placement of intravenous cannulae. It may also be suitable for other kinds of punctures such as ascites drainage and amniocentesis.

Surface anesthesia also facilitates some endoscopic procedures such as bronchoscopy (visualization of the lower airways) or cystoscopy (visualization of the inner surface of the bladder).

Side effects

Localized side effects

The local adverse effects of anesthetic agents include neurovascular manifestations such as prolonged anesthesia (numbness) and paresthesia (tingling, feeling of "pins and needles", or strange sensations). These are symptoms of localized nerve impairment or nerve damage. Of particular note, the use of topical anesthetics for relief of eye pain can result in severe corneal damage.

Risks

The risk of temporary or permanent nerve damage varies between different locations and types of nerve blocks.[2]

Recovery

Permanent nerve damage after a peripheral nerve block is rare. Symptoms are very likely to resolve within a few weeks. The vast majority of those affected (92%–97%), recover within four to six weeks. 99% of these people have recovered within a year. It is estimated that between 1 in 5,000 and 1 in 30,000 nerve blocks result in some degree of permanent persistent nerve damage.[2]

It is suggested that symptoms may continue to improve for up to 18 months following injury.

Causes

Causes of localized symptoms include:

- neurotoxicity due to allergenic reaction,

- excessive fluid pressure in a confined space,

- severing of nerve fibers or support tissue with the needle/catheter,

- injection-site hematoma that puts pressure on the nerve, or

- injection-site infection that produces inflammatory pressure on the nerve and/or necrosis.

General side effects

General systemic adverse effects are due to the pharmacological effects of the anesthetic agents used. The conduction of electric impulses follows a similar mechanism in peripheral nerves, the central nervous system, and the heart. The effects of local anesthetics are therefore not specific for the signal conduction in peripheral nerves. Side effects on the central nervous system and the heart may be severe and potentially fatal. However, toxicity usually occurs only at plasma levels which are rarely reached if proper anesthetic techniques are adhered to. High plasma levels might arise, for example, when doses intended for epidural or intra-support-tissue administration are accidentally delivered as intravascular injection.[3]

Central nervous system

Depending on local tissue concentrations of local anesthetics, there may be excitatory or depressant effects on the central nervous system. Initial symptoms suggest some form of central nervous system excitation such as a ringing in the ears (tinnitus), a metallic taste in the mouth, or tingling or numbness of the mouth. As the concentration rises, a relatively selective depression of inhibitory neurons results in cerebral excitation, which may lead to more advanced symptoms include motor twitching in the periphery followed by grand mal seizures. A profound depression of brain functions occurs at higher concentrations which may lead to coma, respiratory arrest and death.[4] Such tissue concentrations may be due to very high plasma levels after intravenous injection of a large dose. Another possibility is direct exposure of the central nervous system through the CSF, i.e., overdose in spinal anesthesia or accidental injection into the subarachnoid space in epidural anesthesia.

Cardiovascular system

Cardiac toxicity associated with overdose of intravascular injection of local anesthetic is characterized by hypotension, atrioventricular conduction delay, idioventricular rhythms, and eventual cardiovascular collapse. Although all local anesthetics potentially shorten the myocardial refractory period, bupivacaine avidly blocks the cardiac sodium channels, thereby making it most likely to precipitate malignant arrhythmias. Even levobupivacaine and ropivacaine (single-enantiomer derivatives), developed to ameliorate cardiovascular side effects, still harbor the potential to disrupt cardiac function.[5]

Hypersensitivity/allergy

Adverse reactions to local anesthetics (especially the esters) are not uncommon, but true allergy is very rare. Allergic reactions to the esters is usually due to a sensitivity to their metabolite, para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA), and does not result in cross-allergy to amides.[6][7] Therefore, amides can be used as alternatives in those patients. Non-allergic reactions may resemble allergy in their manifestations. In some cases, skin tests and provocative challenge may be necessary to establish a diagnosis of allergy. There are also cases of allergy to paraben derivatives, which are often added as preservatives to local anesthetic solutions.

Methemoglobinemia

Methemoglobinemia is a process where iron in hemoglobin is altered, reducing its oxygen-carrying capability, which produces cyanosis and symptoms of hypoxia. Benzocaine, lidocaine, and prilocaine all produce this effect, especially benzocaine.[6][8] The systemic toxicity of prilocaine is comparatively low, however its metabolite, o-toluidine, is known to cause methemoglobinemia.

Treatment of overdose: "Lipid rescue"

This method of toxicity treatment was invented by Dr. Guy Weinberg in 1998, and had not been widely used until after the first published successful rescue in 2006. There is evidence that Intralipid, a commonly available intravenous lipid emulsion, can be effective in treating severe cardiotoxicity secondary to local anesthetic overdose, including human case reports of successful use in this way ('lipid rescue').[9][10][11][12][13] However, the evidence at this point is still limited.[14]

Though most reports to date have used Intralipid, a commonly available intravenous lipid emulsion, other emulsions, such as Liposyn and Medialipid have also been shown to be effective.

There is ample supporting animal evidence[9][10] and human case reports of successful use in this way.[12][13] In the UK, efforts have been made to publicise this use more widely[11] and lipid rescue has now been officially promoted as a treatment by the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland.[15] There is now one published case report of successful treatment of refractory cardiac arrest in bupropion and lamotrigine overdose using lipid emulsion.[16]

The design of a 'homemade' lipid rescue kit has been described.[17]

Although lipid rescue mechanism of action is not completely understood, it may be that the added lipid in the blood stream acts as a sink, allowing for the removal of lipophilic toxins from affected tissues. This theory is compatible with two studies on lipid rescue for clomipramine toxicity in rabbits[18][19] and with a clinical report on the use of lipid rescue in veterinary medicine to treat a puppy with moxidectin toxicosis.[20]

Mechanism of action

All local anesthetics are membrane stabilizing drugs; they reversibly decrease the rate of depolarization and repolarization of excitable membranes (like nociceptors). Though many other drugs also have membrane stabilizing properties, not all are used as local anesthetics (propranolol, for example). Local anesthetic drugs act mainly by inhibiting sodium influx through sodium-specific ion channels in the neuronal cell membrane, in particular the so-called voltage-gated sodium channels. When the influx of sodium is interrupted, an action potential cannot arise and signal conduction is inhibited. The receptor site is thought to be located at the cytoplasmic (inner) portion of the sodium channel. Local anesthetic drugs bind more readily to sodium channels in an activated state, thus onset of neuronal blockade is faster in neurons that are rapidly firing. This is referred to as state dependent blockade.

Local anesthetics are weak bases and are usually formulated as the hydrochloride salt to render them water-soluble. At a pH equal to the protonated base's pKa, the protonated (ionized) and unprotonated (unionized) forms of the molecule exist in equimolar amounts but only the unprotonated base diffuses readily across cell membranes. Once inside the cell the local anesthetic will be in equilibrium, with the formation of the protonated (ionized form), which does not readily pass back out of the cell. This is referred to as "ion-trapping". In the protonated form, the molecule binds to the local anesthetic binding site on the inside of the ion channel near the cytoplasmic end. Most local anaesthetics work on the internal surface of the membrane - the drug has to penetrate the cell membrane, which is achieved best in the non-ionised form.

Acidosis such as caused by inflammation at a wound partly reduces the action of local anesthetics. This is partly because most of the anesthetic is ionized and therefore unable to cross the cell membrane to reach its cytoplasmic-facing site of action on the sodium channel.

All nerve fibers are sensitive to local anesthetics, but due to a combination of diameter and myelination, fibers have different sensitivities to local anesthetic blockade, termed "Differential Blockade." Type B fibers (sympathetic tone) are the most sensitive followed by Type C (Pain), Type A delta (temperature), Type A gamma (proprioception), Type A beta (sensory touch and pressure) and Type A alpha (motor). Although Type B fibers are thicker than Type C fibers, they are myelinated, and thus are blocked before the unmyelinated, thin C Fiber.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2016) |

Techniques

Local anesthetics can block almost every nerve between the peripheral nerve endings and the central nervous system. The most peripheral technique is topical anesthesia to the skin or other body surface. Small and large peripheral nerves can be anesthetized individually (peripheral nerve block) or in anatomic nerve bundles (plexus anesthesia). Spinal anesthesia and epidural anesthesia merges into the central nervous system.

Injection of local anesthetics is often painful. A number of methods can be used to decrease this pain including buffering of the solution with bicarb and warming.[21]

Clinical techniques include:

- Surface anesthesia - application of local anesthetic spray, solution or cream to the skin or a mucous membrane. The effect is short lasting and is limited to the area of contact.

- Infiltration anesthesia - infiltration of local anesthetic into the tissue to be anesthetized. Surface and infiltration anesthesia are collectively topical anesthesia.

- Field block - subcutaneous injection of a local anesthetic in an area bordering on the field to be anesthetized.

- Peripheral nerve block - injection of local anesthetic in the vicinity of a peripheral nerve to anesthetize that nerve's area of innervation.

- Plexus anesthesia - injection of local anesthetic in the vicinity of a nerve plexus, often inside a tissue compartment that limits the diffusion of the drug away from the intended site of action. The anesthetic effect extends to the innervation areas of several or all nerves stemming from the plexus.

- Epidural anesthesia - a local anesthetic is injected into the epidural space where it acts primarily on the spinal nerve roots. Depending on the site of injection and the volume injected, the anesthetized area varies from limited areas of the abdomen or chest to large regions of the body.

- Spinal anesthesia - a local anesthetic is injected into the cerebrospinal fluid, usually at the lumbar spine (in the lower back), where it acts on spinal nerve roots and part of the spinal cord. The resulting anesthesia usually extends from the legs to the abdomen or chest.

- Intravenous regional anesthesia (Bier's block) - blood circulation of a limb is interrupted using a tourniquet (a device similar to a blood pressure cuff), then a large volume of local anesthetic is injected into a peripheral vein. The drug fills the limb's venous system and diffuses into tissues where peripheral nerves and nerve endings are anesthetized. The anesthetic effect is limited to the area that is excluded from blood circulation and resolves quickly once circulation is restored.

- Local anesthesia of body cavities (e.g. intrapleural anesthesia, intraarticular anesthesia)

- Transincision (or Transwound) catheter anesthesia, wherein a multilumen catheter is inserted through an insicion or wound and aligned across it on the inside as the incision or wound is closed, providing continuous administration of local anesthetic along the incision or wound.[22]

Types

Local anesthetic solutions for injection typically consist of the following ingredients:[23]

- The local anesthetic agent itself

- A vehicle, which is usually water-based or just sterile water

- +/- Vasoconstrictor (see below)

- Reducing agent (antioxidant), e.g. if epinephrine is used then sodium metabisulfite is used as a reducing agent

- Preservative, e.g. methylparaben

- Buffer

Esters are prone to producing allergic reactions, which may necessitate the use of an Amide. The names of each locally clinical anesthetic have the suffix "-caine". Most ester local anesthetics are metabolized by pseudocholinesterase, while amide local anesthetics are metabolized in the liver. This can be a factor in choosing an agent in patients with liver failure,[24] although since cholinesterases are produced in the liver, physiologically (e.g. very young or very old individual) or pathologically (e.g. cirrhosis) impaired hepatic metabolism is also a consideration when using amides.

Sometime local anesthetics are combined together, e.g.:

- Lidocaine/prilocaine (EMLA, eutectic mixture of local anesthetic)

- Lidocaine/tetracaine (Rapydan)

- TAC

Local anesthetic solutions for injection are sometimes mixed with vasoconstrictors (combination drug) to increase the duration of local anesthesia by constricting the blood vessels, thereby safely concentrating the anesthetic agent for an extended duration, as well as reducing hemorrhage.[25] Because the vasoconstrictor temporarily reduces the rate at which the systemic circulation removes the local anesthetic from the area of the injection, the maximum doses of LAs when combined with a vasoconstrictor is higher compared to the same LA without any vasoconstrictor. Occasionally, cocaine is administered for this purpose. Examples include:

- Prilocaine hydrochloride and epinephrine (trade name Citanest Forte)

- Lidocaine, bupivacaine, and epinephrine (recommended final concentrations of 0.5%, 0.25% and 1:200, respectively)

- Iontocaine, consisting of lidocaine and epinephrine

- Septocaine (trade name Septodont), a combination of articaine and epinephrine

One combination product of this type is used topically for surface anaesthesia, TAC (5-12 per cent tetracaine,1/2000 (0.05 per cent, 500 ppm, ½ per mille) adrenaline, 4 or 10 per cent cocaine).

It is safe to use local anesthetic with vasoconstrictor in regions supplied by end arteries. The commonly held belief that local anaesthesia with vasoconstrictor can cause necrosis in extremities such as the nose, ears, fingers and toes due to constriction of end arteries, is invalidated, since no case of necrosis has been reported since the introduction of commercial lidocaine with epinephrine in 1948.[26]

Ester group

- Benzocaine

- Chloroprocaine

- Cocaine

- Cyclomethycaine

- Dimethocaine/Larocaine

- Piperocaine

- Propoxycaine

- Procaine/Novocaine

- Proparacaine

- Tetracaine/Amethocaine

Amide group

- Articaine

- Bupivacaine

- Cinchocaine/Dibucaine

- Etidocaine

- Levobupivacaine

- Lidocaine/Lignocaine

- Mepivacaine

- Prilocaine

- Ropivacaine

- Trimecaine

Naturally derived

Naturally occurring local anesthetics not derived from cocaine are usually neurotoxins, and have the suffix -toxin in their names. [1] Unlike cocaine produced local anesthetics which are intracellular in effect, saxitoxin, neosaxitoxin & tetrodotoxin bind to the extracellular side of sodium channels.

History

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2014) |

It is believed that in Peru the ancient Incas used the leaves of the coca plant as a local anaesthetic in addition to its stimulant properties.[27] It was also used for slave payment and is thought to play a role in the subsequent destruction of Incas culture when Spaniards realized the effects of chewing the coca leaves and took advantage of it.[27] Cocaine was isolated in 1860 and first used as a local anesthetic in 1884. The search for a less toxic and less addictive substitute led to the development of the aminoester local anesthetics stovaine in 1903 and procaine in 1904. Since then, several synthetic local anesthetic drugs have been developed and put into clinical use, notably lidocaine in 1943, bupivacaine in 1957 and prilocaine in 1959.

Shortly after the first use of cocaine for topical anesthesia, blocks on peripheral nerves were described. Brachial plexus anesthesia by percutaneous injection through axillary and supraclavicular approaches was developed in the early 20th century. The search for the most effective and least traumatic approach for plexus anesthesia and peripheral nerve blocks continues to this day. In recent decades, continuous regional anesthesia using catheters and automatic pumps has evolved as a method of pain therapy.

Intravenous regional anesthesia was first described by August Bier in 1908. This technique is still in use and is remarkably safe when drugs of low systemic toxicity such as prilocaine are used.

Spinal anesthesia was first used in 1885 but not introduced into clinical practice until 1899, when August Bier subjected himself to a clinical experiment in which he observed the anesthetic effect, but also the typical side effect of postpunctural headache. Within a few years, spinal anesthesia became widely used for surgical anesthesia and was accepted as a safe and effective technique. Although atraumatic (non-cutting-tip) cannulas and modern drugs are used today, the technique has otherwise changed very little over many decades.

Epidural anesthesia by a caudal approach had been known in the early 20th century, but a well-defined technique using lumbar injection was not developed until 1921, when Fidel Pagés published his article "Anestesia Metamérica". This technique was popularized in the 1930s and 1940s by Achile Mario Dogliotti. With the advent of thin flexible catheters, continuous infusion and repeated injections have become possible, making epidural anesthesia a highly successful technique to this day. Beside its many uses for surgery, epidural anesthesia is particularly popular in obstetrics for the treatment of labor pain.

External links

See also

References

- ^ Brown AR, Weiss R, Greenberg C, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU (1993). "Interscalene block for shoulder arthroscopy: comparison with general anesthesia". Arthroscopy. 9 (3): 295–300. doi:10.1016/S0749-8063(05)80425-6. PMID 8323615.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Nerve damage associated with peripheral nerve block" (PDF). Risks associated with your anaesthetic. Section 12. The Royal College of Anaesthetists. January 2006. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- ^ Zamanian, R., Toxicity, Local Anesthetics (2005)

- ^ Mulroy, M., Systemic Toxicity and Cardiotoxicity From Local Anesthetics (2002)

- ^ Stiles, P; Prielipp (Spring 2009). "RC". Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. 24 (1). Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ a b Dolan, R., ed. (2004), Facial Plastic, Reconstruction, and Trauma Surgery

- ^ Univ. of Wisconsin, Local Anesthesia and Regional Anesthetics

- ^ Univ. of Wisconsin, Local Anesthesia and Regional Anesthetics

- ^ a b Weinberg GL, VadeBoncouer T, Ramaraju GA, Garcia-Amaro MF, Cwik MJ (April 1998). "Pretreatment or resuscitation with a lipid infusion shifts the dose-response to bupivacaine-induced asystole in rats". Anesthesiology. 88 (4): 1071–5. doi:10.1097/00000542-199804000-00028. PMID 9579517.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Weinberg G, Ripper R, Feinstein DL, Hoffman W (2003). "Lipid emulsion infusion rescues dogs from bupivacaine-induced cardiac toxicity". Reg Anesth Pain Med. 28 (3): 198–202. doi:10.1053/rapm.2003.50041. PMID 12772136.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Picard J, Meek T (February 2006). "Lipid emulsion to treat overdose of local anaesthetic: the gift of the glob". Anaesthesia. 61 (2): 107–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04494.x. PMID 16430560.

- ^ a b Rosenblatt MA, Abel M, Fischer GW, Itzkovich CJ, Eisenkraft JB (July 2006). "Successful use of a 20% lipid emulsion to resuscitate a patient after a presumed bupivacaine-related cardiac arrest". Anesthesiology. 105 (1): 217–8. doi:10.1097/00000542-200607000-00033. PMID 16810015.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Litz RJ, Popp M, Stehr SN, Koch T (August 2006). "Successful resuscitation of a patient with ropivacaine-induced asystole after axillary plexus block using lipid infusion". Anaesthesia. 61 (8): 800–1. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2006.04740.x. PMID 16867094.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cave G, Harvey M; Harvey (September 2009). "Intravenous lipid emulsion as antidote beyond local anesthetic toxicity: a systematic review". Acad Emerg Med. 16 (9): 815–24. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00499.x. PMID 19845549.

- ^ Association of Anesthesists of Great Britain and Ireland home page

- ^ Sirianni AJ; Osterhoudt KC; Calello DP; et al. (April 2008). "Use of lipid emulsion in the resuscitation of a patient with prolonged cardiovascular collapse after overdose of bupropion and lamotrigine". Ann Emerg Med. 51 (4): 412–5, 415.e1. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.06.004. PMID 17766009.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Home-made Lipid Rescue Kit

- ^ Harvey M, Cave G; Cave (February 2007). "Intralipid outperforms sodium bicarbonate in a rabbit model of clomipramine toxicity". Ann Emerg Med. 49 (2): 178–85, 185.e1–4. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.07.016. PMID 17098328.

- ^ Harvey M, Cave G, Hoggett K; Cave; Hoggett (February 2009). "Correlation of plasma and peritoneal diasylate clomipramine concentration with hemodynamic recovery after intralipid infusion in rabbits". Acad Emerg Med. 16 (2): 151–6. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00313.x. PMID 19133855.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Crandell DE, Weinberg GL; Weinberg (April 2009). "Moxidectin toxicosis in a puppy successfully treated with intravenous lipids". J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio). 19 (2): 181–6. doi:10.1111/j.1476-4431.2009.00402.x. PMID 19691569.

- ^ "BestBets: The Effect of Warming Local Anaesthetics on Pain of Infiltration".

- ^ Kampe, S.; Warm, M.; Kasper, S. -M.; Diefenbach, C. (2003). "Concept for postoperative analgesia after pedicled TRAM flaps: Continuous wound instillation with 0.2% ropivacaine via multilumen catheters. A report of two cases". British Journal of Plastic Surgery. 56 (5): 478–483. doi:10.1016/S0007-1226(03)00180-2. PMID 12890461.

- ^ "Allergic Reactions". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ Arnold Stern (2002). Pharmacology: PreTest self-assessment and review. New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division. ISBN 0-07-136704-7.

- ^ Yagiela JA (1995). "Vasoconstrictor agents for local anesthesia". Anesth Prog. 42 (3–4): 116–20. PMC 2148913. PMID 8934977.

- ^ Nielsen LJ, Lumholt P, Halmich LR (Oct 2014). "[Local anaesthesia with vasoconstrictor is safe to use in areas with end-arteries in fingers, toes, noses and ears.]". Ugeskrift for Lægerer. 176: 44. PMID 25354008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Cocaine's use: From the Incas to the U.S." Boca Raton News. 4 April 1985. Retrieved 2 February 2014.