Noble gas

Template:Periodic table (noble gases) The noble gases make a group of chemical elements with similar properties: under standard conditions, they are all odorless, colorless, monatomic gases with very low chemical reactivity. The six noble gases that occur naturally are helium (He), neon (Ne), argon (Ar), krypton (Kr), xenon (Xe), and the radioactive radon (Rn).

For the first six periods of the periodic table, the noble gases are exactly the members of group 18 of the periodic table. It is possible that due to relativistic effects, the group 14 element flerovium exhibits some noble-gas-like properties,[1] instead of the group 18 element ununoctium.[2] Noble gases are typically highly unreactive except when under particular extreme conditions. The inertness of noble gases makes them very suitable in applications where reactions are not wanted. For example: argon is used in lightbulbs to prevent the hot tungsten filament from oxidizing; also, helium is breathed by deep-sea divers to prevent oxygen and nitrogen toxicity.

The properties of the noble gases can be well explained by modern theories of atomic structure: their outer shell of valence electrons is considered to be "full", giving them little tendency to participate in chemical reactions, and it has been possible to prepare only a few hundred noble gas compounds. The melting and boiling points for a given noble gas are close together, differing by less than 10 °C (18 °F); that is, they are liquids over only a small temperature range.

Neon, argon, krypton, and xenon are obtained from air in an air separation unit using the methods of liquefaction of gases and fractional distillation. Helium is sourced from natural gas fields which have high concentrations of helium in the natural gas, using cryogenic gas separation techniques, and radon is usually isolated from the radioactive decay of dissolved radium compounds. Noble gases have several important applications in industries such as lighting, welding, and space exploration. A helium-oxygen breathing gas is often used by deep-sea divers at depths of seawater over 55 m (180 ft) to keep the diver from experiencing oxygen toxemia, the lethal effect of high-pressure oxygen, and nitrogen narcosis, the distracting narcotic effect of the nitrogen in air beyond this partial-pressure threshold. After the risks caused by the flammability of hydrogen became apparent, it was replaced with helium in blimps and balloons.

History

Noble gas is translated from the German noun [Edelgas] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), first used in 1898 by Hugo Erdmann[3] to indicate their extremely low level of reactivity. The name makes an analogy to the term "noble metals", which also have low reactivity. The noble gases have also been referred to as inert gases, but this label is deprecated as many noble gas compounds are now known.[4] Rare gases is another term that was used,[5] but this is also inaccurate because argon forms a fairly considerable part (0.94% by volume, 1.3% by mass) of the Earth's atmosphere.[6]

Pierre Janssen and Joseph Norman Lockyer discovered a new element on August 18, 1868 while looking at the chromosphere of the Sun, and named it helium after the Greek word for the Sun, ήλιος (ílios or helios).[7] No chemical analysis was possible at the time, but helium was later found to be a noble gas. Before them, in 1784, the English chemist and physicist Henry Cavendish had discovered that air contains a small proportion of a substance less reactive than nitrogen.[8] A century later, in 1895, Lord Rayleigh discovered that samples of nitrogen from the air were of a different density than nitrogen resulting from chemical reactions. Along with Scottish scientist William Ramsay at University College, London, Lord Rayleigh theorized that the nitrogen extracted from air was mixed with another gas, leading to an experiment that successfully isolated a new element, argon, from the Greek word αργός (argós, "inactive").[8] With this discovery, they realized an entire class of gases was missing from the periodic table. During his search for argon, Ramsay also managed to isolate helium for the first time while heating cleveite, a mineral. In 1902, having accepted the evidence for the elements helium and argon, Dmitri Mendeleev included these noble gases as group 0 in his arrangement of the elements, which would later become the periodic table.[9]

Ramsay continued to search for these gases using the method of fractional distillation to separate liquid air into several components. In 1898, he discovered the elements krypton, neon, and xenon, and named them after the Greek words κρυπτός (kryptós, "hidden"), νέος (néos, "new"), and ξένος (xénos, "stranger"), respectively. Radon was first identified in 1898 by Friedrich Ernst Dorn,[10] and was named radium emanation, but was not considered a noble gas until 1904 when its characteristics were found to be similar to those of other noble gases.[11] Rayleigh and Ramsay received the 1904 Nobel Prizes in Physics and in Chemistry, respectively, for their discovery of the noble gases;[12][13] in the words of J. E. Cederblom, then president of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, "the discovery of an entirely new group of elements, of which no single representative had been known with any certainty, is something utterly unique in the history of chemistry, being intrinsically an advance in science of peculiar significance".[13]

The discovery of the noble gases aided in the development of a general understanding of atomic structure. In 1895, French chemist Henri Moissan attempted to form a reaction between fluorine, the most electronegative element, and argon, one of the noble gases, but failed. Scientists were unable to prepare compounds of argon until the end of the 20th century, but these attempts helped to develop new theories of atomic structure. Learning from these experiments, Danish physicist Niels Bohr proposed in 1913 that the electrons in atoms are arranged in shells surrounding the nucleus, and that for all noble gases except helium the outermost shell always contains eight electrons.[11] In 1916, Gilbert N. Lewis formulated the octet rule, which concluded an octet of electrons in the outer shell was the most stable arrangement for any atom; this arrangement caused them to be unreactive with other elements since they did not require any more electrons to complete their outer shell.[14]

In 1962 Neil Bartlett discovered the first chemical compound of a noble gas, xenon hexafluoroplatinate.[15] Compounds of other noble gases were discovered soon after: in 1962 for radon, radon difluoride,[16] and in 1963 for krypton, krypton difluoride (KrF

2).[17] The first stable compound of argon was reported in 2000 when argon fluorohydride (HArF) was formed at a temperature of 40 K (−233.2 °C; −387.7 °F).[18]

In December 1998, scientists at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research working in Dubna, Russia bombarded plutonium (Pu) with calcium (Ca) to produce a single atom of element 114,[19] flerovium (Fl).[20] Preliminary chemistry experiments have indicated this element may be the first superheavy element to show abnormal noble-gas-like properties, even though it is a member of group 14 on the periodic table.[21] In October 2006, scientists from the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory successfully created synthetically ununoctium (Uuo), the seventh element in group 18,[22] by bombarding californium (Cf) with calcium (Ca).[23]

Physical and atomic properties

| Property[11][24] | Helium | Neon | Argon | Krypton | Xenon | Radon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density (g/dm3) | 0.1786 | 0.9002 | 1.7818 | 3.708 | 5.851 | 9.97 |

| Boiling point (K) | 4.4 | 27.3 | 87.4 | 121.5 | 166.6 | 211.5 |

| Melting point (K) | 0.95[25] | 24.7 | 83.6 | 115.8 | 161.7 | 202.2 |

| Enthalpy of vaporization (kJ/mol) | 0.08 | 1.74 | 6.52 | 9.05 | 12.65 | 18.1 |

| Solubility in water at 20 °C (cm3/kg) | 8.61 | 10.5 | 33.6 | 59.4 | 108.1 | 230 |

| Atomic number | 2 | 10 | 18 | 36 | 54 | 86 |

| Atomic radius (calculated) (pm) | 31 | 38 | 71 | 88 | 108 | 120 |

| Ionization energy (kJ/mol) | 2372 | 2080 | 1520 | 1351 | 1170 | 1037 |

| Allen electronegativity[26] | 4.16 | 4.79 | 3.24 | 2.97 | 2.58 | 2.60 |

The noble gases have weak interatomic force, and consequently have very low melting and boiling points. They are all monatomic gases under standard conditions, including the elements with larger atomic masses than many normally solid elements.[11] Helium has several unique qualities when compared with other elements: its boiling and melting points are lower than those of any other known substance; it is the only element known to exhibit superfluidity; it is the only element that cannot be solidified by cooling under standard conditions—a pressure of 25 standard atmospheres (2,500 kPa; 370 psi) must be applied at a temperature of 0.95 K (−272.200 °C; −457.960 °F) to convert it to a solid.[27] The noble gases up to xenon have multiple stable isotopes. Radon has no stable isotopes; its longest-lived isotope, 222Rn, has a half-life of 3.8 days and decays to form helium and polonium, which ultimately decays to lead.[11]

The noble gas atoms, like atoms in most groups, increase steadily in atomic radius from one period to the next due to the increasing number of electrons. The size of the atom is related to several properties. For example, the ionization potential decreases with an increasing radius because the valence electrons in the larger noble gases are farther away from the nucleus and are therefore not held as tightly together by the atom. Noble gases have the largest ionization potential among the elements of each period, which reflects the stability of their electron configuration and is related to their relative lack of chemical reactivity.[24] Some of the heavier noble gases, however, have ionization potentials small enough to be comparable to those of other elements and molecules. It was the insight that xenon has an ionization potential similar to that of the oxygen molecule that led Bartlett to attempt oxidizing xenon using platinum hexafluoride, an oxidizing agent known to be strong enough to react with oxygen.[15] Noble gases cannot accept an electron to form stable anions; that is, they have a negative electron affinity.[28]

The macroscopic physical properties of the noble gases are dominated by the weak van der Waals forces between the atoms. The attractive force increases with the size of the atom as a result of the increase in polarizability and the decrease in ionization potential. This results in systematic group trends: as one goes down group 18, the atomic radius, and with it the interatomic forces, increases, resulting in an increasing melting point, boiling point, enthalpy of vaporization, and solubility. The increase in density is due to the increase in atomic mass.[24]

The noble gases are nearly ideal gases under standard conditions, but their deviations from the ideal gas law provided important clues for the study of intermolecular interactions. The Lennard-Jones potential, often used to model intermolecular interactions, was deduced in 1924 by John Lennard-Jones from experimental data on argon before the development of quantum mechanics provided the tools for understanding intermolecular forces from first principles.[29] The theoretical analysis of these interactions became tractable because the noble gases are monatomic and the atoms spherical, which means that the interaction between the atoms is independent of direction, or isotropic.

Chemical properties

The noble gases are colorless, odorless, tasteless, and nonflammable under standard conditions. They were once labeled group 0 in the periodic table because it was believed they had a valence of zero, meaning their atoms cannot combine with those of other elements to form compounds. However, it was later discovered some do indeed form compounds, causing this label to fall into disuse.[11]

Like other groups, the members of this family show patterns in its electron configuration, especially the outermost shells resulting in trends in chemical behavior:

| Z | Element | No. of electrons/shell |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | helium | 2 |

| 10 | neon | 2, 8 |

| 18 | argon | 2, 8, 8 |

| 36 | krypton | 2, 8, 18, 8 |

| 54 | xenon | 2, 8, 18, 18, 8 |

| 86 | radon | 2, 8, 18, 32, 18, 8 |

The noble gases have full valence electron shells. Valence electrons are the outermost electrons of an atom and are normally the only electrons that participate in chemical bonding. Atoms with full valence electron shells are extremely stable and therefore do not tend to form chemical bonds and have little tendency to gain or lose electrons.[30] However, heavier noble gases such as radon are held less firmly together by electromagnetic force than lighter noble gases such as helium, making it easier to remove outer electrons from heavy noble gases.

Noble gas notation

As a result of a full shell, the noble gases can be used in conjunction with the electron configuration notation to form the noble gas notation. To do this, the nearest noble gas that precedes the element in question is written first, and then the electron configuration is continued from that point forward. For example, the electron notation of Phosphorus is 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p3, while the noble gas notation is [Ne] 3s2 3p3. This more compact notation makes it easier to identify elements, and is shorter than writing out the full notation of atomic orbitals.[31]

Compounds

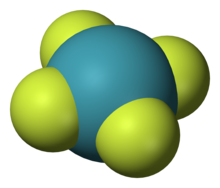

4, one of the first noble gas compounds to be discovered

The noble gases show extremely low chemical reactivity; consequently, only a few hundred noble gas compounds have been formed. Neutral compounds in which helium and neon are involved in chemical bonds have not been formed (although there is some theoretical evidence for a few helium compounds), while xenon, krypton, and argon have shown only minor reactivity.[32] The reactivity follows the order Ne < He < Ar < Kr < Xe < Rn.

In 1933, Linus Pauling predicted that the heavier noble gases could form compounds with fluorine and oxygen. He predicted the existence of krypton hexafluoride (KrF

6) and xenon hexafluoride (XeF

6), speculated that XeF

8 might exist as an unstable compound, and suggested xenic acid could form perxenate salts.[33][34] These predictions were shown to be generally accurate, except that XeF

8 is now thought to be both thermodynamically and kinetically unstable.[35]

Xenon compounds are the most numerous of the noble gas compounds that have been formed.[36] Most of them have the xenon atom in the oxidation state of +2, +4, +6, or +8 bonded to highly electronegative atoms such as fluorine or oxygen, as in xenon difluoride (XeF

2), xenon tetrafluoride (XeF

4), xenon hexafluoride (XeF

6), xenon tetroxide (XeO

4), and sodium perxenate (Na

4XeO

6). Xenon reacts with fluorine to form numerous xenon fluorides according to the following equations:

- Xe + F2 → XeF2

- Xe + 2F2 → XeF4

- Xe + 3F2 → XeF6

Some of these compounds have found use in chemical synthesis as oxidizing agents; XeF

2, in particular, is commercially available and can be used as a fluorinating agent.[37] As of 2007, about five hundred compounds of xenon bonded to other elements have been identified, including organoxenon compounds (containing xenon bonded to carbon), and xenon bonded to nitrogen, chlorine, gold, mercury, and xenon itself.[32][38] Compounds of xenon bound to boron, hydrogen, bromine, iodine, beryllium, sulphur, titanium, copper, and silver have also been observed but only at low temperatures in noble gas matrices, or in supersonic noble gas jets.[32]

In theory, radon is more reactive than xenon, and therefore should form chemical bonds more easily than xenon does. However, due to the high radioactivity and short half-life of radon isotopes, only a few fluorides and oxides of radon have been formed in practice.[39]

Krypton is less reactive than xenon, but several compounds have been reported with krypton in the oxidation state of +2.[32] Krypton difluoride is the most notable and easily characterized. Under extreme conditions, krypton reacts with fluorine to form KrF2 according to the following equation:

- Kr + F2 → KrF2

Compounds in which krypton forms a single bond to nitrogen and oxygen have also been characterized,[40] but are only stable below −60 °C (−76 °F) and −90 °C (−130 °F) respectively.[32]

Krypton atoms chemically bound to other nonmetals (hydrogen, chlorine, carbon) as well as some late transition metals (copper, silver, gold) have also been observed, but only either at low temperatures in noble gas matrices, or in supersonic noble gas jets.[32] Similar conditions were used to obtain the first few compounds of argon in 2000, such as argon fluorohydride (HArF), and some bound to the late transition metals copper, silver, and gold.[32] As of 2007, no stable neutral molecules involving covalently bound helium or neon are known.[32]

The noble gases—including helium—can form stable molecular ions in the gas phase. The simplest is the helium hydride molecular ion, HeH+, discovered in 1925.[41] Because it is composed of the two most abundant elements in the universe, hydrogen and helium, it is believed to occur naturally in the interstellar medium, although it has not been detected yet.[42] In addition to these ions, there are many known neutral excimers of the noble gases. These are compounds such as ArF and KrF that are stable only when in an excited electronic state; some of them find application in excimer lasers.

In addition to the compounds where a noble gas atom is involved in a covalent bond, noble gases also form non-covalent compounds. The clathrates, first described in 1949,[43] consist of a noble gas atom trapped within cavities of crystal lattices of certain organic and inorganic substances. The essential condition for their formation is that the guest (noble gas) atoms must be of appropriate size to fit in the cavities of the host crystal lattice. For instance, argon, krypton, and xenon form clathrates with hydroquinone, but helium and neon do not because they are too small or insufficiently polarizable to be retained.[44] Neon, argon, krypton, and xenon also form clathrate hydrates, where the noble gas is trapped in ice.[45]

Noble gases can form endohedral fullerene compounds, in which the noble gas atom is trapped inside a fullerene molecule. In 1993, it was discovered that when C

60, a spherical molecule consisting of 60 carbon atoms, is exposed to noble gases at high pressure, complexes such as He@C

60 can be formed (the @ notation indicates He is contained inside C

60 but not covalently bound to it).[46] As of 2008, endohedral complexes with helium, neon, argon, krypton, and xenon have been obtained.[47] These compounds have found use in the study of the structure and reactivity of fullerenes by means of the nuclear magnetic resonance of the noble gas atom.[48]

2 according to the 3-center-4-electron bond model

Noble gas compounds such as xenon difluoride (XeF

2) are considered to be hypervalent because they violate the octet rule. Bonding in such compounds can be explained using a three-center four-electron bond model.[49][50] This model, first proposed in 1951, considers bonding of three collinear atoms. For example, bonding in XeF

2 is described by a set of three molecular orbitals (MOs) derived from p-orbitals on each atom. Bonding results from the combination of a filled p-orbital from Xe with one half-filled p-orbital from each F atom, resulting in a filled bonding orbital, a filled non-bonding orbital, and an empty antibonding orbital. The highest occupied molecular orbital is localized on the two terminal atoms. This represents a localization of charge which is facilitated by the high electronegativity of fluorine.[51]

The chemistry of heavier noble gases, krypton and xenon, are well established. The chemistry of the lighter ones, argon and helium, is still at an early stage, while a neon compound is still yet to be identified.

Occurrence and production

The abundances of the noble gases in the universe decrease as their atomic numbers increase. Helium is the most common element in the universe after hydrogen, with a mass fraction of about 24%. Most of the helium in the universe was formed during Big Bang nucleosynthesis, but the amount of helium is steadily increasing due to the fusion of hydrogen in stellar nucleosynthesis (and, to a very slight degree, the alpha decay of heavy elements).[52][53] Abundances on Earth follow different trends; for example, helium is only the third most abundant noble gas in the atmosphere. The reason is that there is no primordial helium in the atmosphere; due to the small mass of the atom, helium cannot be retained by the Earth's gravitational field.[54] Helium on Earth comes from the alpha decay of heavy elements such as uranium and thorium found in the Earth's crust, and tends to accumulate in natural gas deposits.[54] The abundance of argon, on the other hand, is increased as a result of the beta decay of potassium-40, also found in the Earth's crust, to form argon-40, which is the most abundant isotope of argon on Earth despite being relatively rare in the Solar System. This process is the base for the potassium-argon dating method.[55] Xenon has an unexpectedly low abundance in the atmosphere, in what has been called the missing xenon problem; one theory is that the missing xenon may be trapped in minerals inside the Earth's crust.[56] After the discovery of xenon dioxide, a research showed that Xe can substitute for Si in the quartz.[57] Radon is formed in the lithosphere as from the alpha decay of radium. It can seep into buildings through cracks in their foundation and accumulate in areas that are not well ventilated. Due to its high radioactivity, radon presents a significant health hazard; it is implicated in an estimated 21,000 lung cancer deaths per year in the United States alone.[58]

| Abundance | Helium | Neon | Argon | Krypton | Xenon | Radon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solar System (for each atom of silicon)[59] | 2343 | 2.148 | 0.1025 | 5.515 × 10−5 | 5.391 × 10−6 | – |

| Earth's atmosphere (volume fraction in ppm)[60] | 5.20 | 18.20 | 9340.00 | 1.10 | 0.09 | (0.06–18) × 10−19[61] |

| Igneous rock (mass fraction in ppm)[24] | 3 × 10−3 | 7 × 10−5 | 4 × 10−2 | – | – | 1.7 × 10−10 |

| Gas | 2004 price (USD/m3)[62] |

|---|---|

| Helium (industrial grade) | 4.20–4.90 |

| Helium (laboratory grade) | 22.30–44.90 |

| Argon | 2.70–8.50 |

| Neon | 60–120 |

| Krypton | 400–500 |

| Xenon | 4000–5000 |

For large-scale use, helium is extracted by fractional distillation from natural gas, which can contain up to 7% helium.[63]

Neon, argon, krypton, and xenon are obtained from air using the methods of liquefaction of gases, to convert elements to a liquid state, and fractional distillation, to separate mixtures into component parts. Helium is typically produced by separating it from natural gas, and radon is isolated from the radioactive decay of radium compounds.[11] The prices of the noble gases are influenced by their natural abundance, with argon being the cheapest and xenon the most expensive. As an example, the table to the right lists the 2004 prices in the United States for laboratory quantities of each gas.

Applications

Noble gases have very low boiling and melting points, which makes them useful as cryogenic refrigerants.[64] In particular, liquid helium, which boils at 4.2 K (−268.95 °C; −452.11 °F), is used for superconducting magnets, such as those needed in nuclear magnetic resonance imaging and nuclear magnetic resonance.[65] Liquid neon, although it does not reach temperatures as low as liquid helium, also finds use in cryogenics because it has over 40 times more refrigerating capacity than liquid helium and over three times more than liquid hydrogen.[61]

Helium is used as a component of breathing gases to replace nitrogen, due its low solubility in fluids, especially in lipids. Gases are absorbed by the blood and body tissues when under pressure like in scuba diving, which causes an anesthetic effect known as nitrogen narcosis.[66] Due to its reduced solubility, little helium is taken into cell membranes, and when helium is used to replace part of the breathing mixtures, such as in trimix or heliox, a decrease in the narcotic effect of the gas at depth is obtained.[67] Helium's reduced solubility offers further advantages for the condition known as decompression sickness, or the bends.[11][68] The reduced amount of dissolved gas in the body means that fewer gas bubbles form during the decrease in pressure of the ascent. Another noble gas, argon, is considered the best option for use as a drysuit inflation gas for scuba diving.[69] Helium is also used as filling gas in nuclear fuel rods for nuclear reactors.[70]

Since the Hindenburg disaster in 1937,[71] helium has replaced hydrogen as a lifting gas in blimps and balloons due to its lightness and incombustibility, despite an 8.6%[72] decrease in buoyancy.[11]

In many applications, the noble gases are used to provide an inert atmosphere. Argon is used in the synthesis of air-sensitive compounds that are sensitive to nitrogen. Solid argon is also used for the study of very unstable compounds, such as reactive intermediates, by trapping them in an inert matrix at very low temperatures.[73] Helium is used as the carrier medium in gas chromatography, as a filler gas for thermometers, and in devices for measuring radiation, such as the Geiger counter and the bubble chamber.[62] Helium and argon are both commonly used to shield welding arcs and the surrounding base metal from the atmosphere during welding and cutting, as well as in other metallurgical processes and in the production of silicon for the semiconductor industry.[61]

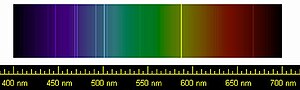

Noble gases are commonly used in lighting because of their lack of chemical reactivity. Argon, mixed with nitrogen, is used as a filler gas for incandescent light bulbs.[61] Krypton is used in high-performance light bulbs, which have higher color temperatures and greater efficiency, because it reduces the rate of evaporation of the filament more than argon; halogen lamps, in particular, use krypton mixed with small amounts of compounds of iodine or bromine.[61] The noble gases glow in distinctive colors when used inside gas-discharge lamps, such as "neon lights". These lights are called after neon but often contain other gases and phosphors, which add various hues to the orange-red color of neon. Xenon is commonly used in xenon arc lamps which, due to their nearly continuous spectrum that resembles daylight, find application in film projectors and as automobile headlamps.[61]

The noble gases are used in excimer lasers, which are based on short-lived electronically excited molecules known as excimers. The excimers used for lasers may be noble gas dimers such as Ar2, Kr2 or Xe2, or more commonly, the noble gas is combined with a halogen in excimers such as ArF, KrF, XeF, or XeCl. These lasers produce ultraviolet light which, due to its short wavelength (193 nm for ArF and 248 nm for KrF), allows for high-precision imaging. Excimer lasers have many industrial, medical, and scientific applications. They are used for microlithography and microfabrication, which are essential for integrated circuit manufacture, and for laser surgery, including laser angioplasty and eye surgery.[74]

Some noble gases have direct application in medicine. Helium is sometimes used to improve the ease of breathing of asthma sufferers.[61] Xenon is used as an anesthetic because of its high solubility in lipids, which makes it more potent than the usual nitrous oxide, and because it is readily eliminated from the body, resulting in faster recovery.[75] Xenon finds application in medical imaging of the lungs through hyperpolarized MRI.[76] Radon, which is highly radioactive and is only available in minute amounts, is used in radiotherapy.[11]

Discharge color

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Helium | Neon | Argon | Krypton | Xenon |

The color of gas discharge emission depends on several factors, including the following:[77]

- discharge parameters (local value of current density and electric field, temperature, etc. – note the color variation along the discharge in the top row);

- gas purity (even small fraction of certain gases can affect color);

- material of the discharge tube envelope – note suppression of the UV and blue components in the bottom-row tubes made of thick household glass.

See also

- Noble gas (data page), for extended tables of physical properties.

- Noble metal, for metals that are resistant to corrosion or oxidation.

- Inert gas, for any gas that is not reactive under normal circumstances.

- Industrial gas

- Neutronium

- Noble gas configuration

Notes

- ^ "Flerov laboratory of nuclear reactions" (PDF). JINR. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ Nash, Clinton S. (2005). "Atomic and Molecular Properties of Elements 112, 114, and 118". J. Phys. Chem. A. 109 (15): 3493–3500. doi:10.1021/jp050736o. PMID 16833687.

- ^ Renouf, Edward (1901). "Noble gases". Science. 13 (320): 268–270. Bibcode:1901Sci....13..268R. doi:10.1126/science.13.320.268.

- ^ Ojima 2002, p. 30

- ^ Ojima 2002, p. 4

- ^ "argon". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary (1989), s.v. "helium". Retrieved December 16, 2006, from Oxford English Dictionary Online. Also, from quotation there: Thomson, W. (1872). Rep. Brit. Assoc. xcix: "Frankland and Lockyer find the yellow prominences to give a very decided bright line not far from D, but hitherto not identified with any terrestrial flame. It seems to indicate a new substance, which they propose to call Helium."

- ^ a b Ojima 2002, p. 1

- ^ Mendeleev 1903, p. 497

- ^ Partington, J. R. (1957). "Discovery of Radon". Nature. 179 (4566): 912. Bibcode:1957Natur.179..912P. doi:10.1038/179912a0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Noble Gas". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008.

- ^ Cederblom, J. E. (1904). "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1904 Presentation Speech".

- ^ a b Cederblom, J. E. (1904). "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1904 Presentation Speech".

- ^ Gillespie, R. J.; Robinson, E. A. (2007). "Gilbert N. Lewis and the chemical bond: the electron pair and the octet rule from 1916 to the present day". J Comput Chem. 28 (1): 87–97. doi:10.1002/jcc.20545. PMID 17109437.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Bartlett, N. (1962). "Xenon hexafluoroplatinate Xe+[PtF6]–". Proceedings of the Chemical Society (6): 218. doi:10.1039/PS9620000197.

- ^ Fields, Paul R.; Stein, Lawrence; Zirin, Moshe H. (1962). "Radon Fluoride". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 84 (21): 4164–4165. doi:10.1021/ja00880a048.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Grosse, A. V.; Kirschenbaum, A. D.; Streng, A. G.; Streng, L. V. (1963). "Krypton Tetrafluoride: Preparation and Some Properties". Science. 139 (3559): 1047–1048. Bibcode:1963Sci...139.1047G. doi:10.1126/science.139.3559.1047. PMID 17812982.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Khriachtchev, Leonid; Pettersson, Mika; Runeberg, Nino; Lundell, Jan; Räsänen, Markku (2000). "A stable argon compound". Nature. 406 (6798): 874–876. doi:10.1038/35022551. PMID 10972285.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; Utyonkov, V.; Lobanov, Yu.; Abdullin, F.; Polyakov, A.; Tsyganov; Gulbekian; Bogomolov; Gikal; Mezentsev; Iliev; Subbotin; Sukhov; Buklanov; Subotic; Itkis; Moody; Wild; Stoyer; Stoyer; Lougheed; et al. (1999). "Synthesis of Superheavy Nuclei in the 48Ca + 244Pu Reaction". Physical Review Letters. 83 (16). American Physical Society: 3154. Bibcode:1999PhRvL..83.3154O. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.3154.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author6=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|first5=(help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ Woods, Michael (2003-05-06). "Chemical element No. 110 finally gets a name—darmstadtium". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ "Gas Phase Chemistry of Superheavy Elements" (PDF). Texas A&M University. Retrieved 2008-05-31.

- ^ Robert C. Barber, Paul J. Karol, Hiromichi Nakahara,

Emanuele Vardaci, and Erich W. Vogt (2011). "Discovery of the elements with atomic numbers greater than or equal to 113 (IUPAC Technical Report)*" (PDF). Pure Appl. Chem. 83 (7). IUPAC. doi:10.1515/ci.2011.33.5.25b. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

{{cite journal}}: line feed character in|author=at position 53 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; Utyonkov, V.; Lobanov, Yu.; Abdullin, F.; Polyakov, A.; Shirokovsky, I.; Tsyganov, Yu.; Voinov, A.; Gulbekian, G.; Bogomolov, S.; Gikal, B.; Mezentsev, A.; Iliev, S.; Subbotin, V.; Sukhov, A.; Subotic, K.; Zagrebaev, V.; Vostokin, G.; Itkis, M.; Moody, K.; Patin, J.; Shaughnessy, D.; Stoyer, M.; Stoyer, N.; Wilk, P.; Kenneally, J.; Landrum, J.; Wild, J.; Lougheed, R.; et al. (2006). "Synthesis of the isotopes of elements 118 and 116 in the 249

Cf

and 245

Cm

+ 48

Ca

fusion reactions". Physical Review C. 74 (4): 44602. Bibcode:2006PhRvC..74d4602O. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.74.044602.{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author6=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|first5=(help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Greenwood 1997, p. 891

- ^ Under pressure of 25 bar

- ^ Allen, Leland C. (1989). "Electronegativity is the average one-electron energy of the valence-shell electrons in ground-state free atoms". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 111 (25): 9003. doi:10.1021/ja00207a003.

- ^ "Solid Helium". University of Alberta. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ Wheeler, John C. (1997). "Electron Affinities of the Alkaline Earth Metals and the Sign Convention for Electron Affinity". Journal of Chemical Education. 74: 123–127. Bibcode:1997JChEd..74..123W. doi:10.1021/ed074p123.; Kalcher, Josef; Sax, Alexander F. (1994). "Gas Phase Stabilities of Small Anions: Theory and Experiment in Cooperation". Chemical Reviews. 94 (8): 2291–2318. doi:10.1021/cr00032a004.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mott, N. F. (1955). "John Edward Lennard-Jones. 1894–1954". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 1: 175–184. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1955.0013.

- ^ Ojima 2002, p. 35

- ^ CliffsNotes 2007, p. 15

- ^ a b c d e f g h Grochala, Wojciech (2007). "Atypical compounds of gases, which have been called noble". Chemical Society Reviews. 36 (10): 1632–1655. doi:10.1039/b702109g. PMID 17721587.

- ^ Pauling, Linus (1933). "The Formulas of Antimonic Acid and the Antimonates". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 55 (5): 1895–1900. doi:10.1021/ja01332a016.

- ^ Holloway 1968

- ^ Seppelt, Konrad (1979). "Recent developments in the Chemistry of Some Electronegative Elements". Accounts of Chemical Research. 12 (6): 211–216. doi:10.1021/ar50138a004.

- ^ Moody, G. J. (1974). "A Decade of Xenon Chemistry". Journal of Chemical Education. 51 (10): 628–630. Bibcode:1974JChEd..51..628M. doi:10.1021/ed051p628. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- ^ Zupan, Marko; Iskra, Jernej; Stavber, Stojan (1998). "Fluorination with XeF2. 44. Effect of Geometry and Heteroatom on the Regioselectivity of Fluorine Introduction into an Aromatic Ring". J. Org. Chem. 63 (3): 878–880. doi:10.1021/jo971496e. PMID 11672087.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Harding 2002, pp. 90–99

- ^ .Avrorin, V. V.; Krasikova, R. N.; Nefedov, V. D.; Toropova, M. A. (1982). "The Chemistry of Radon". Russian Chemical Review. 51 (1): 12–20. Bibcode:1982RuCRv..51...12A. doi:10.1070/RC1982v051n01ABEH002787.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lehmann, J (2002). "The chemistry of krypton". Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 233–234: 1–39. doi:10.1016/S0010-8545(02)00202-3.

- ^ Hogness, T. R.; Lunn, E. G. (1925). "The Ionization of Hydrogen by Electron Impact as Interpreted by Positive Ray Analysis". Physical Review. 26: 44–55. Bibcode:1925PhRv...26...44H. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.26.44.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fernandez, J.; Martin, F. (2007). "Photoionization of the HeH2+ molecular ion". J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 40 (12): 2471–2480. Bibcode:2007JPhB...40.2471F. doi:10.1088/0953-4075/40/12/020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ H. M. Powell and M. Guter (1949). "An Inert Gas Compound". Nature. 164 (4162): 240–241. Bibcode:1949Natur.164..240P. doi:10.1038/164240b0.

- ^ Greenwood 1997, p. 893

- ^ Dyadin, Yuri A.; et al. (1999). "Clathrate hydrates of hydrogen and neon". Mendeleev Communications. 9 (5): 209–210. doi:10.1070/MC1999v009n05ABEH001104.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Saunders, M.; Jiménez-Vázquez, H. A.; Cross, R. J.; Poreda, R. J. (1993). "Stable compounds of helium and neon. He@C60 and Ne@C60". Science. 259 (5100): 1428–1430. Bibcode:1993Sci...259.1428S. doi:10.1126/science.259.5100.1428. PMID 17801275.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Saunders, Martin; Jimenez-Vazquez, Hugo A.; Cross, R. James; Mroczkowski, Stanley; Gross, Michael L.; Giblin, Daryl E.; Poreda, Robert J. (1994). "Incorporation of helium, neon, argon, krypton, and xenon into fullerenes using high pressure". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116 (5): 2193–2194. doi:10.1021/ja00084a089.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Frunzi, Michael; Cross, R. Jame; Saunders, Martin (2007). "Effect of Xenon on Fullerene Reactions". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 129 (43): 13343–6. doi:10.1021/ja075568n. PMID 17924634.

- ^ Greenwood 1997, p. 897

- ^ Weinhold 2005, pp. 275–306

- ^ Pimentel, G. C. (1951). "The Bonding of Trihalide and Bifluoride Ions by the Molecular Orbital Method". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 19 (4): 446–448. Bibcode:1951JChPh..19..446P. doi:10.1063/1.1748245.

- ^ Weiss, Achim. "Elements of the past: Big Bang Nucleosynthesis and observation". Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- ^ Coc, A.; et al. (2004). "Updated Big Bang Nucleosynthesis confronted to WMAP observations and to the Abundance of Light Elements". Astrophysical Journal. 600 (2): 544. arXiv:astro-ph/0309480. Bibcode:2004ApJ...600..544C. doi:10.1086/380121.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b Pine, P. (1955). "Radiogenic Origin of the Helium Isotopes in Rock". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 62 (3): 71–92. Bibcode:1955NYASA..62...71M. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1955.tb35366.x.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help) - ^ Scherer, Alexandra (2007-01-16). "40Ar/39Ar dating and errors". Technische Universität Bergakademie Freiberg. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ Sanloup (2005). "Retention of Xenon in Quartz and Earth's Missing Xenon". Science. 310 (5751): 1174–1177. Bibcode:2005Sci...310.1174S. doi:10.1126/science.1119070. PMID 16293758.

{{cite journal}}:|first1=missing|last1=(help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ Tyler Irving (May 2011). "Xenon Dioxide May Solve One of Earth's Mysteries". L’Actualité chimique canadienne (Canadian Chemical News). Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ^ "A Citizen's Guide to Radon". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2007-11-26. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1086/375492 , please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1086/375492instead. - ^ "The Atmosphere". National Weather Service. Retrieved 2008-06-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g Häussinger, Peter; Glatthaar, Reinhard; Rhode, Wilhelm; Kick, Helmut; Benkmann, Christian; Weber, Josef; Wunschel, Hans-Jörg; Stenke, Viktor; Leicht, Edith; Stenger, Hermann (2002). "Noble gases". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley. doi:10.1002/14356007.a17_485.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hwang, Shuen-Chen; Lein, Robert D.; Morgan, Daniel A. (2005). "Noble Gases". Kirk Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. Wiley. pp. 343–383. doi:10.1002/0471238961.0701190508230114.a01.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Winter, Mark (2008). "Helium: the essentials". University of Sheffield. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ^ "Neon". Encarta. 2008.

- ^ Zhang, C. J.; Zhou, X. T.; Yang, L. (1992). "Demountable coaxial gas-cooled current leads for MRI superconducting magnets". Magnetics, IEEE Transactions on. 28 (1). IEEE: 957–959. Bibcode:1992ITM....28..957Z. doi:10.1109/20.120038.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fowler, B; Ackles, K. N.; Porlier, G. (1985). "Effects of inert gas narcosis on behavior—a critical review". Undersea Biomed. Res. 12 (4): 369–402. ISSN 0093-5387. OCLC 2068005. PMID 4082343. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- ^ Bennett 1998, p. 176

- ^ Vann, R. D. (ed) (1989). "The Physiological Basis of Decompression". 38th Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society Workshop. 75(Phys)6-1-89: 437. Retrieved 2008-05-31.

{{cite journal}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Maiken, Eric (2004-08-01). "Why Argon?". Decompression. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ Horhoianu, G; Ionescu, D.V; Olteanu, G (1999). "Thermal behaviour of CANDU type fuel rods during steady state and transient operating conditions". Annals of Nuclear Energy. 26 (16): 1437. doi:10.1016/S0306-4549(99)00022-5.

- ^ "Disaster Ascribed to Gas by Experts". The New York Times. 1937-05-07. p. 1.

- ^ Freudenrich, Craig (2008). "How Blimps Work". HowStuffWorks. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- ^ Dunkin, I. R. (1980). "The matrix isolation technique and its application to organic chemistry". Chem. Soc. Rev. 9: 1–23. doi:10.1039/CS9800900001.

- ^ Basting, Dirk; Marowsky, Gerd (2005). Excimer Laser Technology. Springer. ISBN 3-540-20056-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sanders, Robert D.; Ma, Daqing; Maze, Mervyn (2005). "Xenon: elemental anaesthesia in clinical practice". British Medical Bulletin. 71 (1): 115–135. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldh034. PMID 15728132.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Albert, M. S.; Balamore, D. (1998). "Development of hyperpolarized noble gas MRI". Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A. 402 (2–3): 441–453. Bibcode:1998NIMPA.402..441A. doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(97)00888-7. PMID 11543065.

- ^ Ray, Sidney F. (1999). Scientific photography and applied imaging. Focal Press. pp. 383–384. ISBN 0-240-51323-1.

References

- Bennett, Peter B.; Elliott, David H. (1998). The Physiology and Medicine of Diving. SPCK Publishing. ISBN 0-7020-2410-4.

- Bobrow Test Preparation Services (2007-12-05). CliffsAP Chemistry. CliffsNotes. ISBN 0-470-13500-X.

- Greenwood, N. N.; Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Oxford:Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-3365-4.

- Harding, Charlie J.; Janes, Rob (2002). Elements of the P Block. Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 0-85404-690-9.

- Holloway, John H. (1968). Noble-Gas Chemistry. London: Methuen Publishing. ISBN 0-412-21100-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Mendeleev, D. (1902–1903). Osnovy Khimii (The Principles of Chemistry) (in Russian) (7th ed.).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Ojima, Minoru; Podosek, Frank A. (2002). Noble Gas Geochemistry. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80366-7.

- Weinhold, F.; Landis, C. (2005). Valency and bonding. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83128-8.

- Scerri, Eric R. (2007). The Periodic Table, Its Story and Its Significance. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-530573-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)