Puerto Rican Independence Party

Puerto Rican Independence Party Partido Independentista Puertorriqueño | |

|---|---|

| President | Rubén Berríos Martínez |

| Secretary-General | Juan Dalmau Ramírez Manuel Rodríguez Orellana |

| Vice-president | María de Lourdes Santiago Negrón |

| Executive President | Fernando Martín García |

| Representative | Víctor García San Inocencio |

| Founded | October 20, 1946 |

| Headquarters | San Juan, Puerto Rico |

| Youth wing | Juventud PIP |

| Ideology | Puerto Rican independence[1] Social democracy |

| Political position | Center-left |

| International affiliation | Socialist International |

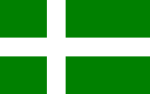

| Colors | Green & White |

| Seats in the Senate | 1 / 27 |

| Seats in the House of Representatives | 1 / 51 |

| Municipalities | 0 / 78 |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| www.independencia.net | |

The Puerto Rican Independence Party (Template:Lang-es, PIP) is a social-democratic[2][3] political party in Puerto Rico that campaigns for the independence of Puerto Rico from United States suzerainty.[4]

Those who follow the PIP ideology are usually called independentistas, pipiolos, or sometimes just pro-independence activists.[5]

History

The party began as the electoral wing of the Puerto Rican independence movement. It is the largest of the independence parties, and the only one that is on the ballot during elections (other candidates must be added in by hand). In 1948, two years after being founded, the PIP gathered 10.2% of the votes in the island. In 1952, two years after an armed uprising of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party, it obtained 19% of the votes, its highest electoral support ever, which made it the second electoral party on the island for a moment. In 1956 it took 12.4% of the votes; in 1960 3.1%; in 1964, 4%; in 1968, 3.5; in 1972, 5.4; in 1976, 5.7; in 1980, 5.4; in 1984, 3.6, and in 1988, 5.5. In 2004 it obtained 2.7% of the votes, and in 2008 it took 2%.[6]

Foundation

The party was founded on 20 October 1946, by Gilberto Concepción de Gracia (1909–1968) and his colleague Fernando Milán Suárez. They felt the independence movement had been "betrayed" by the Popular Democratic Party, whose ultimate goal had originally been independence.

FBI surveillance of the party

In 2003, The New York Times reported the following about the Federal Bureau of Investigation publicly admitting it had directed "tremendously destructive" efforts against various organizations, including the Puerto Rican Independence Party:

- "They include a 1961 directive from Mr. Hoover to seek information on 12 independence movement leaders, six of them operating in New York, "concerning their weaknesses, morals, criminal records, spouses, children, family life, educational qualifications and personal activities other than independence activities." The instructions were given under the domestic surveillance program known as Cointelpro, which aimed at aggressively monitoring antiwar, leftist and other groups in the United States and disrupting them.

- In the case of Puerto Rican independence groups, J. Edgar Hoover's 1961 memo refers to 'our efforts to disrupt their activities and compromise their effectiveness."[7] Scholars say the papers provide invaluable additions to the recorded history of Puerto Rico. "I expect that this will alter somewhat the analysis of why independence hasn't made it,' said Félix V. Matos Rodríguez, director of the center at Hunter[citation needed]. 'In the 1940s, independence was the second-largest political movement in the island, (after support for commonwealth status), and a real alternative. But it was criminalized.'

- The existence of the FBI papers came to light during a US House of Representatives Appropriations Subcommittee hearing in 2000, when Representative José E. Serrano of New York questioned Louis J. Freeh, then FBI director, on the issue. Freeh gave the first public acknowledgment of the federal government's Puerto Rican surveillance and offered a mea culpa.

- 'Your question goes back to a period, particularly in the 1960s, when the F.B.I. did operate a program that did tremendous destruction to many people, to the country and certainly to the F.B.I.,' Freeh said, according to transcripts of the hearing. Freeh said that he would make the files available 'and see if we can redress some of the egregious illegal action, maybe criminal action, that occurred in the past'.".[8]

The FBI's surveillance of any person or organization advocating Puerto Rico's independence has been recognized by the FBI's top leadership.[9]

The FBI's past surveillance of the pro-independence movement is detailed in 1.8 million documents, a fraction of which were released in 2000.[10][11]

Then FBI Director Louis Freeh made an unprecedented admission to the effects that the FBI had engaged in egregious and illegal action from the 1930s to the 1990s, quite possibly involving the FBI in widespread crimes and violation of Constitutional rights against Puerto Ricans.[9][11] He stunned a congressional budget hearing by conceding that his agency had violated the civil rights of many Puerto Ricans over the years and had engaged in "egregious illegal action, maybe criminal action."[12]

1970s

In 1971, the PIP gubernatorial candidate, Rubén Berríos led a protest against the US Navy in Culebra.[13][14] During the 1972 elections, the PIP showed the largest growth in its history while running a democratic socialist, pro-worker, pro-poor campaign. One year later during a delegate assembly Rubén Berríos declared that the party was not presenting a Marxist–Leninist platform and took the matter to the PIP's assembly which voted in favor of the party's current stance in favor of social democracy.[citation needed] The Marxist–Leninist faction, called the "terceristas", split into several groups. The biggest of them went into the Popular Socialist Movement, while the rest went into the Puerto Rican Socialist Party.

1990s

| Part of a series on |

| Social democracy |

|---|

|

In 1999, PIP leaders, especially Rubén Berríos, became involved in the Navy-Vieques protests started by many citizens of Vieques against the presence of the US military in the island-municipality (see also: Cause of Vieques).[15]

2008 election

During the 2008 elections, the PIP lost official recognition for the second time, obtaining 2.04% of the gubernatorial vote. Loss of recognition was official on January 2, 2009. The minimum vote percentage to keep official recognition is 3.0% as per the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico law. The party also lost both of its seats in the legislature, where they had had one seat in each house.

In May, 2009, the party submitted more than 100,000 signed petitions to the Puerto Rico's elections commission and regained legal status.[16]

2012 election

During the 2012 elections, the PIP lost official recognition for the third time, obtaining 2.5% of the gubernatorial vote. Loss of recognition will be official on January 2, 2013. The minimum vote percentage to keep official recognition is 3.0% as per the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico law. [17]

International support

The PIP cause receives moral support by international organizations. Examples of these are the Socialist International (the largest organization of political parties in the world), including fifteen political parties which are in power in Latin America. The government of Cuba also supports it, as well as the ex-president of Panama, Martín Torrijos, and a wide group of world-recognized writers and artists.[18][19]

On January 26, 2007, the Nobel Prize laureate Gabriel García Márquez joined other figures such as Mario Benedetti, Ernesto Sábato, Thiago de Mello, Eduardo Galeano, Carlos Monsiváis, Pablo Armando Fernández, Jorge Enrique Adoum, Pablo Milanés, Luis Rafael Sánchez, Mayra Montero and Ana Lydia Vega, in supporting independence for Puerto Rico and joining the Latin American and Caribbean Congress in Solidarity with Puerto Rico's Independence, which approved a resolution favoring the island's right to assert its independence, as ratified unanimously by political parties hailing from 22 countries in November 2006. García Márquez's push for the recognition of Puerto Rico's independence was obtained at the behest of the Puerto Rican Independence Party. His pledge for support to the Puerto Rican Independence Movement was part of a wider effort that emerged from the Latin American and Caribbean Congress in Solidarity with Puerto Rico's Independence.

PIP anti-war mobilization and protests

As reported in numerous media, the PIP's leadership and active members participated in anti-war protests and mobilization to resist the Iraq war and oppose the U.S. government's efforts to encourage Puerto Ricans to enlist in the U.S. Armed Forces. The Washington Post wrote in August 2007 that "on this island with a long tradition of military service, pro-independence advocates are tapping the territory's growing anti-Iraq war sentiment to revitalize their cause. As a result, 57 percent of Puerto Rico's 10th-, 11th- and 12th-graders, or their parents, have signed forms over the past year withholding contact information from the Pentagon. ... For five years, PIP has issued opt-out forms to about 120,000 students in Puerto Rico and encouraged them to sign—and independista activists expect this year to mark their most successful effort yet."[20] The article also quoted Juan Dalmau, then-secretary general of the Puerto Rican Independence Party as saying: if the death of a Puerto Rican soldier is tragic, it's more tragic if that soldier has no say in that war [with Iraq]" and that he did not want the children of Puerto Rico to become "colonial cannon meat."

Another article in The Progressive also reported on PIP's anti-war activity. It was written three years earlier, in 2004, but it still noted that "some groups like the Puerto Rico Bar Association and the Independence Party have registered strong protests against the deployments. In an attempt to draw attention to Puerto Ricans' lack of elected representatives, even the usually pro-U.S. statehood party has raised concerns about the disproportionate body count suffered by islanders."[21] Two years later, it was reported that PIP, along with hundreds of other supporters of Puerto Rican independence "blocked the entrance to the U.S. Federal Courthouse here on Feb. 20 to denounce recent FBI raids against the homes and workplaces of ... supporters of Puerto Rican independence...and the growing repression by the FBI against the independence movement in general." This demonstration reportedly marked the beginning of PIP "campaign to get the FBI out of Puerto Rico."[22]

PIP stance on Puerto Rico's economic crisis and taxation system

During the 2005-2007 Puerto Rico economic crisis, the Puerto Rican Independence Party submitted various bills that would have taxed corporations making $1 million or more in annual net profits an extra ten percent above the average tax rate these corporations pay, which hovers around 5%.[23] The PNP and the PPD parties amended the bill, taxing the corporations the traditional lower rate, while the general population was taxed at a ceiling of about 33.3% for income tax plus a 7.5% sales tax.[23] Despite objections presented by the PIP, the PNP and PPD also allowed the companies to claim the additional tax as a credit on next year's bill, making the "tax", in effect, a one-year loan. Puerto Rico has been said "There is no place in the territorial limits of the United States that provides such an advantageous base for exporters. " Because of this, many US companies moved their headquarters and manufacturing facilities there. This is why the PNP and PPD believed the tax increase would exacerbate the problems[23][24]

Party symbol

The flag's green color stands for the hope of becoming free, and the white cross stands for the sacrifice and commitment of the party with democracy.[citation needed] The flag's design is based on the first national flag ever flown by Puerto Ricans, which is also the current flag of the municipality of Lares, location where the first relatively successful attempt of revolutionary insurgency in Puerto Rico, called Grito de Lares, took place on September 23, 1868. The Lares flag is, on the other hand, similar to that of the Dominican Republic, since the Grito's mastermind, Ramón Emeterio Betances, not only admired the Dominican pro-independence struggle, but was also a descendant of Dominicans himself. This nationalist uprising was the foundation for other uprisings to come in the future, such as the Grito de Yara in Cuba, the March 1st Movement in Korea.[dubious – discuss] The party's flag is based on the Nordic Cross flag design. Nordic Cross flags, or Latin cross flags, are a common design in Scandinavia and other parts of the world, and in theory, the PIP's emblem belongs to this family of flags.

Disfranchisement due to residence in Puerto Rico

United States citizens residing in the U.S. commonwealth of Puerto Rico do not hold the right to vote in U.S. presidential elections. Although Puerto Rican residents elect a Resident Commissioner to the United States House of Representatives, that official may not participate in votes determining the final passage of legislation. Furthermore, Puerto Rico holds no representation of any kind in the United States Senate.

Both the Puerto Rican Independence Party and the New Progressive Party of Puerto Rico officially oppose the island's political status quo and consider Puerto Rico's lack of federal representation to be disfranchisement. The remaining political organization, the Popular Democratic Party, is less active in its opposition of this case of disfranchisement but has officially stated that it favors fixing the remaining "deficits of democracy" that the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations have publicly recognized in writing through Presidential Task Force Reports.

Important party leaders

- Rubén Berríos – President, former Senator and Honorary President of the Socialist International (SI)

- Manuel Rodríguez Orellana – Secretary of Relations with North America

- Fernando Martín – Executive President, former Senator

- María de Lourdes Santiago Negrón – Vice-President, Senator

- Juan Dalmau Ramírez – Secretary General & Electoral Commissioner

- Prof. Edwin Irizarry Mora – Secretary of Economic Affairs

- David Noriega – Former Representative. Gubernatorial candidate in 1996 general elections. He resigned from the party in the late 1990s.

- Roberto Iván Aponte – Secretary of Municipal Organization

- Dr. Luis Roberto Piñero – President of the Pro-Independence Advocates' Campaign in favor of unifying both Houses of the Legislature into a single, unicameral Parliament

- Víctor García San Inocencio – Former Representative

- Jorge Fernández Porto – Adviser on Environmental Sciences and Public Policy Affairs

- Jessica Martínez – Member of Pro-Independence Advocates' Campaign in Favor of a single, unicameral Parliament

- Dr. Gilberto Concepción de Gracia – Founding President and respected Latin American Leader

See also

- Latin American and Caribbean Congress in Solidarity with Puerto Rico's Independence

- Puerto Rico political parties

- Puerto Rican Socialist Party

- Cause of Vieques

- Maravilla Hill case

- Navy-Culebra protests

- Navy-Vieques protests

- Politics of Puerto Rico

- Socialist International

References

- ^ National Performances: The Politics of Class, Race, and Space in Puerto Rican Chicago. Ana Y. Ramos-Zayas. University of Chicago Press. 2003. Pages 21-22. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ^ Lester McGrath-Andino (2005). "Intifada: Church–State Conflict in Vieques, Puerto Rico". In Gastón Espinosa; Virgilio P. Elizondo; Jesse Miranda (eds.). Latino Religions and Civic Activism in the United States. Oxford University Press. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-19-516228-8.

- ^ Alfredo Lopez (1987). Dona Licha's Island: Modern Colonialism in Puerto Rico. South End Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-89608-257-1.

- ^ Berrios-Martinez, Ruben; "Puerto rico—Lithuania in Reverse?"; The Washington Post, Pg. A23; May 23, 1990.

- ^ Wallace, Carol J.; "Translating Laughter: Humor as a Special Challenge in Translating the Stories of Ana Lydia Vega"; The Journal of the Midwest Modern Language Association (MLA), Vol. 35, No. 2, Translating in and across Cultures (Autumn, 2002), pp. 75-87

- ^ Comisión estatal de elecciones de Puerto Rico. "web site". www.ceepur.org.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Fernandez, Ronald (1 Jan 1996). The Disenchanted Island: Puerto Rico and the United States in the Twentieth Century. Greenwood Publishing Group,. p. 213.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "Decades of FBI Surveillance of Puerto Rican Groups by Mireya Navarro". Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ a b "El Diario/LA PRENSA OnLine". Archived from the original on 23 February 2008. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ "pr-secretfiles.net". Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ a b "pr-secretfiles.net". Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ America's Colony By Pedro A. Malavet, page 95 Accessed July 14, 2009.

- ^ The New York Times, "Protesters on Culebra Scuffle With Marines"; pg. 13, January 19, 1971. At that time, he was found guilty of trespassing federal lands and incarcerated for three months at Fox River State Penitentiary (see also: Navy-Culebra protests).

- ^ Berrios Martinez, Ruben; "From a Puerto Rican Prison"; The New York Times, pg. 47, April 28, 1971.

- ^ ABC News: Dozens of Puerto Rican Protesters Arrested - Marshals Raid Activists' Homes; by Vilma Perez, July 3, 2000.

- ^ "Puerto Rican Independence Party Regains Legal Status". Latin American Herald Tribune. 2009-15-2009. Retrieved 2009-05-16.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "El Vocero de Puerto Rico". Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ "Panama requests Latin America to support Puerto Rican independence"; Dominican Today; November 19, 2006

- ^ "Prominentes figuras de América Latina apoyan la independencia de Puerto Rico - Escritores y artistas declaran su adhesión a la Proclama de Panamá" www.independencia.net/topicos/panama/cpi_panama_nov06.html

- ^ "Recruiting For Iraq War Undercut in Puerto Rico". Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ "Puerto Rican involvement in Iraq comes with no representation - The Progressive". Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ "Puerto Rican Independence Party protests FBI attacks on activists and the". Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ a b c Cruz, José A.; "Puerto Rico's crisis highlights its colonial status"; People's Weekly World. (National Edition). New York: Jun 17-Jun 23, 2006. Vol. 21, Iss. 3; pg. 7.

- ^ "-- Offshore Manual - We walk the walk, and talk the talk! --". Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- Puerto Rican Independence Party (1998). Retrieved January 6, 2004 from www.independencia.net/ingles/welcome.html

External links

Website

- Pro-independence parties

- Political parties in Puerto Rico

- Social democratic parties

- Socialism in Puerto Rico

- Political parties established in 1946

- National liberation movements

- Political history of Puerto Rico

- Separatism in the United States

- Nationalist parties in the United States

- Secessionist organizations

- Politics of the Americas

- Politics of the Caribbean

- Politics of Puerto Rico

- Independence movements

- Puerto Rican nationalism

- Nationalist organizations

- Puerto Rican independence movement

- Secessionist organizations in the United States