Robert J. Shiller

Robert J. Shiller | |

|---|---|

Shiller in July 2017 | |

| Born | Robert James Shiller March 29, 1946 |

| Academic career | |

| Field | Financial economics Behavioral finance |

| Institution | Yale University |

| School or tradition | New Keynesian economics Behavioral economics |

| Alma mater | Kalamazoo College University of Michigan (BA) Massachusetts Institute of Technology (PhD) |

| Doctoral advisor | Franco Modigliani |

| Doctoral students | John Y. Campbell[1] |

| Influences | John Maynard Keynes George Akerlof Irving Fisher |

| Contributions | Irrational Exuberance, Case-Shiller index, CAPE-ratio |

| Awards | Deutsche Bank Prize (2009) Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics (2013) |

| Information at IDEAS / RePEc | |

| Academic background | |

| Thesis | Rational expectations and the structure of interest rates (1972) |

| Signature | |

| |

Robert James Shiller (born March 29, 1946)[4] is an American economist, academic, and author. As of 2022,[5] he served as a Sterling Professor of Economics at Yale University and is a fellow at the Yale School of Management's International Center for Finance.[6] Shiller has been a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) since 1980, was vice president of the American Economic Association in 2005, its president-elect for 2016, and president of the Eastern Economic Association for 2006–2007.[7] He is also the co‑founder and chief economist of the investment management firm MacroMarkets LLC.

In 2003, he co-authored a Brookings Institution paper called "Is There a Bubble in the Housing Market?", and in 2005 he warned that "further rises in the [stock and housing] markets could lead, eventually, to even more significant declines... A long-run consequence could be a decline in consumer and business confidence, and another, possibly worldwide, recession." Writing in The Wall Street Journal in August 2006, Shiller again warned that "there is significant risk of a ... possible recession sooner than most of us expected.", and in September 2007, almost exactly one year before the collapse of Lehman Brothers, Shiller wrote an article in which he predicted an imminent collapse in the U.S. housing market, and subsequent financial panic.

Shiller was ranked by the IDEAS RePEc publications monitor in 2008 as among the 100 most influential economists of the world;[8] and was still on the list in 2019.[9] Eugene Fama, Lars Peter Hansen and Shiller jointly received the 2013 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, "for their empirical analysis of asset prices".[10][11]

Background

[edit]Shiller was born in Detroit, Michigan, the son of Ruth R. (née Radsville) and Benjamin Peter Shiller, an engineer-cum-entrepreneur.[12] He is of Lithuanian descent.[13] He is married to Virginia Marie (Faulstich), a psychologist, and has two children.[12] He was raised as a Methodist.[14]

Shiller attended Kalamazoo College for two years before transferring to the University of Michigan where he graduated Phi Beta Kappa with a B.A. degree in 1967.[15] He received the S.M. degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1968, and his Ph.D. from MIT in 1972 with thesis entitled Rational expectations and the structure of interest rates under the supervision of Franco Modigliani.[3]

Career

[edit]Shiller has taught at Yale since 1982, and previously held faculty positions at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Minnesota, also giving frequent lectures at the London School of Economics. He has written on economic topics that range from behavioral finance to real estate to risk management, and has been co-organizer of NBER workshops on behavioral finance with Richard Thaler since 1991. His book Macro Markets won TIAA-CREF's first annual Paul A. Samuelson Award. He currently publishes a syndicated column and has been a regular contributor to Project Syndicate since 2003.

In 1981 Shiller published an article in which he challenged the efficient-market hypothesis, which was the dominant view in the economics profession at the time.[16] Shiller argued that in a rational stock market, investors would base stock prices on the expected receipt of future dividends, discounted to a present value. He examined the performance of the U.S. stock market since the 1920s, and considered the kinds of expectations of future dividends and discount rates that could justify the wide range of variation experienced in the stock market. Shiller concluded that the volatility of the stock market was greater than could plausibly be explained by any rational view of the future. This article was later named as one of the "top 20" articles in the 100-year history of the American Economic Association.

The behavioral finance school gained new credibility following the October 1987 stock market crash. Shiller's work included survey research that asked investors and stock traders what motivated them to make trades; the results further bolstered his hypothesis that these decisions are often driven by emotion instead of rational calculation. Much of this survey data has been gathered continuously since 1989.[17]

In 1991 he formed Case Shiller Weiss with economists Karl Case and Allan Weiss who served as the CEO from inception to the sale to Fiserv.[20] The company produced a repeat-sales index using home sales prices data from across the nation, studying home pricing trends. The index was developed by Shiller and Case when Case was studying unsustainable house pricing booms in Boston and Shiller was studying the behavioral aspects of economic bubbles.[20] The repeat-sales index developed by Case and Shiller was later acquired and further developed by Fiserv and Standard & Poor, creating the Case-Shiller index.[20]

His book Irrational Exuberance (2000) – a New York Times bestseller – warned that the stock market had become a bubble in March 2000 (the very height of the market top), which could lead to a sharp decline.

On CNBC's "How to Profit from the Real Estate Boom" in 2005, he noted that housing price rises could not outstrip inflation in the long term because, except for land restricted sites, house prices would tend toward building costs plus normal economic profit. Co‑panelist David Lereah disagreed. In February, Lereah had put out his book Are You Missing the Real Estate Boom? signaling the market top for housing prices. While Shiller repeated his precise timing again for another market bubble, because the general level of nationwide residential real estate prices do not reveal themselves until after a lag of about one year, people did not believe Shiller had called another top until late 2006 and early 2007.

Shiller was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 2003.[21]

That same year, he co-authored a Brookings Institution paper entitled "Is There a Bubble in the Housing Market?". Shiller subsequently refined his position in the 2nd edition of Irrational Exuberance (2005), acknowledging that "further rises in the [stock and housing] markets could lead, eventually, to even more significant declines... A long-run consequence could be a decline in consumer and business confidence, and another, possibly worldwide, recession. This extreme outcome ... is not inevitable, but it is a much more serious risk than is widely acknowledged." Writing in The Wall Street Journal in August 2006, Shiller again warned that "there is significant risk of a very bad period, with slow sales, slim commissions, falling prices, rising default and foreclosures, serious trouble in financial markets, and a possible recession sooner than most of us expected."[22] In September 2007, almost exactly one year before the collapse of Lehman Brothers, Shiller wrote an article in which he predicted an imminent collapse in the U.S. housing market, and subsequent financial panic.[23]

Shiller was awarded the Deutsche Bank Prize in Financial Economics in 2009 for his pioneering research in the field of financial economics, relating to the dynamics of asset prices, such as fixed income, equities, and real estate, and their metrics. His work has been influential in the development of the theory as well as its implications for practice and policy making. His contributions on risk sharing, financial market volatility, bubbles and crises, have received widespread attention among academics, practitioners, and policymakers alike.[24] In 2010, he was named by Foreign Policy magazine to its list of top global thinkers.[25]

In 2010 Shiller supported the idea that to fix the financial and banking systems, in order to avoid future financial crisis, banks need to issue a new kind of debt, known as contingent capital, that automatically converts into equity if the regulators determine that there is a systemic national financial crisis, and if the bank is simultaneously in violation of capital-adequacy.[26]

In 2011 he attained the Bloomberg 50 most influential people in global finance ranking list.[27] In 2012, Thomson Reuters named him a contender for that year's Nobel Prize in Economics, citing his "pioneering contributions to financial market volatility and the dynamics of asset prices".[28]

On October 14, 2013, it was announced that Shiller had received the 2013 Nobel Prize in Economics alongside Eugene Fama and Lars Peter Hansen.[29]

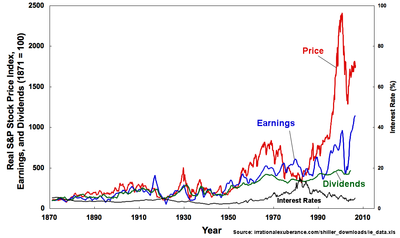

His lecture at the prize ceremony explained why markets are not efficient. He presented an argument on why Eugene Fama's Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) was fallacious. EMH postulates that the present value of an asset reflects the efficient incorporation of information into prices. According to Shiller, the results of the movement of the market are extremely erratic, unlike Fama's assertion where the movement would be smoother if it would reflect the intrinsic value of the assets. The results of the graphs provided by Shiller showed a clear aberration from that of the Efficient Market Hypothesis. For example, the dividend growth had been 2% per year on stocks. However, it contradicted the EMH since the growth did not reflect the expected dividends. It is further explained by Shiller's Linearized Present Value model, which is a result of collaboration with his colleague and former student John Campbell, that only one-half to one-third of the fluctuations in the stock market are explained by the expected dividends model. Also, in the lecture, Shiller pointed out that variables such as interest rates and building costs did not explain the movement of the housing market.

On the other hand, Shiller believes that more information regarding the asset market is crucial for its efficiency. Additionally, he alluded to John Maynard Keynes's explanation of stock markets to point out the irrationality of people while making decisions. Keynes compared the stock market to a beauty contest where people instead of betting on who they find attractive, bet on the contestant who the majority of people find attractive. Therefore, he believes that people do not use complicated mathematical calculations and a sophisticated economic model while participating in the asset market. He argued that a huge set of data is required for the market to operate efficiently. Since there were very minuscule data available on the asset markets for his research, let alone for the common people, he developed the Case-Shiller index that provides information about the trends in home prices. Thus, he added that the use of modern technology can benefit economists to accrue data of broader asset classes that will make the market more information-based and the prices more efficient.

In interviews in June 2015, Shiller warned of the potential of a stock market crash.[30] In August 2015, after a flash crash in individual stocks, he continued to see bubbly conditions in stocks, bonds and housing.[31]

In 2015, the Council for Economic Education honored Shiller with its Visionary Award.[32]

In 2017, Shiller was quoted as calling Bitcoin the biggest financial bubble at the time.[33] The perceived failure of the Cincinnati Time Store has been used as an analogy to suggest that cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin are a "speculative bubble" waiting to burst, according to economist Robert J. Shiller.[34]

In 2019, Shiller published Narrative Economics. The book received favourable reviews and was selected among the Best books of 2019 list published by the Financial Times.[35]

Works

[edit]Books

[edit]- Narrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic Events, Robert J. Shiller, Princeton University Press (2019), ISBN 978-0691182292.

- Phishing for Phools: The Economics of Manipulation and Deception, George A. Akerlof and Robert J. Shiller, Princeton University Press (2015), ISBN 978-0-691-16831-9.

- Finance and the Good Society, Robert J. Shiller, Princeton University Press (2012), ISBN 0-691-15488-0.

- Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism, George A. Akerlof and Robert J. Shiller, Princeton University Press (2009), ISBN 978-0-691-14233-3.

- The Subprime Solution: How Today's Global Financial Crisis Happened, and What to Do about It, Robert J. Shiller, Princeton University Press (2008), ISBN 0-691-13929-6.

- The New Financial Order: Risk in the 21st Century, Robert J. Shiller, Princeton University Press (2003), ISBN 0-691-09172-2.

- Irrational Exuberance, Robert J Shiller, Princeton University Press (2000), ISBN 0-691-05062-7.

- Macro Markets: Creating Institutions for Managing Society's largest Economic Risks, Robert J. Shiller, Clarendon Press, New York: Oxford University Press (1993), ISBN 0-19-828782-8.

- Market Volatility, Robert J. Shiller, MIT Press (1990), ISBN 0-262-19290-X.

Op-eds

[edit]Shiller has written op-eds since at least 2007 for such publications as The New York Times, where he has appeared in print on at least two dozen occasions.

- In "The Transformation of the American Dream",[36] Shiller starts his history lesson on the evolution of language in 1931 with James Truslow Adams's "dream of... opportunity for each according to his ability or achievement", through a chaplain's "equal opportunity for all men" (1954) to the Allard and Sessions (108th Congress) 2003 American Dream Downpayment Act, which was designed for the Secretary of Housing "to assist low-income families to achieve homeownership".[37]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Campbell, John Y. (2004), "An Interview with Robert J. Shiller", Macroeconomic Dynamics, 8 (5), Cambridge University Press: 649–683, doi:10.1017/S1365100504040027, S2CID 154975037

- ^ Grove, Lloyd. "World According to ... Robert Shiller". Portfolio.com. Retrieved June 26, 2009.

- ^ a b Blaug, Mark; Vane, Howard R. (2003). Who's who in economics (4 ed.). Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84064-992-5.

- ^ "The Closing: Robert Shiller". The Real Deal. November 1, 2007. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- ^ "The Yale Economics 2022 Annual Magazine Marks a New Era for the Department". Yale Department of Economics. Retrieved December 28, 2022.

- ^ "ICF Fellows". About. Yale University School of Management. Retrieved September 21, 2012.

- ^ "Past Presidents". Eastern Economic Association. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- ^ "Economist Rankings at IDEAS". University of Connecticut. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- ^ "Economist Rankings at IDEAS". University of Connecticut. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- ^ * Robert J. Shiller on Nobelprize.org , accessed 12 October 2020

- ^ "3 US Economists Win Nobel for Work on Asset Prices", ABC News, October 14, 2013

- ^ a b Shiller, Robert J. 1946, Contemporary Authors, New Revision Series, Encyclopedia.com

- ^ Read, Colin (2012). "The Early Years". The Early Years : Palgrave Connect. doi:10.1057/9781137292216.0036. ISBN 9781137292216.

- ^ "Robert Shiller on Human Traits Essential to Capitalism". Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ Van Sweden, James (October 22, 2013). "Alumnus Wins Nobel Prize". www.kzoo.edu. Kalamazoo College. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ Shiller, Robert J. (1981). "Do Stock Prices Move Too Much to Be Justified by Subsequent Changes in Dividends?". American Economic Review. 71 (3): 421–436. JSTOR 1802789.

- ^ "Stock Market Confidence Indices". Yale School Of Management. July 14, 2013. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ^ a b c Shiller, Robert (2005). Irrational Exuberance (2d ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12335-6.

- ^ "source". Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- ^ a b c Benner, Katie (July 7, 2009). "Bob Shiller didn't kill the housing market". CNNMoney.com. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved September 21, 2021.

- ^ ""No One Saw This Coming": Understanding Financial Crisis Through Accounting Models" (PDF). Munich Personal RePEc Archive. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 6, 2015. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- ^ Shiller, Robert J. (September 17, 2007). "Bubble Trouble". Project Syndicate. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- ^ "Center for Financial Studies : Home". Ifk-cfs.de. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ^ "The FP top 100 global thinkers". Foreign Policy Magazine. December 2010.

- ^ "Engineering Financial Stability". January 18, 2010.

- ^ "The 50 Most Influential People in Global Finance". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012.

- ^ Pendlebury, David A. "Understanding Market Volatility". ScienceWatch – 2012 Predictions. Thomson Reuters. Retrieved September 21, 2012.

- ^ "The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 013". Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ^ "Understanding Asset Bubbles and How to React to Them". www.aaii.com. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- ^ "Yale's Robert Shiller: Stock Market Turmoil Not Over Yet". Fox Business. August 25, 2015. Archived from the original on December 26, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- ^ "Visionary Awards: Celebrate with CEE the leaders of Economic Education".

- ^ "ROBERT SHILLER: Bitcoin is the 'best example right now' of a bubble". Business Insider. September 5, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- ^ Bartenstein, Ben; Russo, Camila (May 21, 2018). "Yale's Shiller warns crypto may be another Cincinnati time store". San Francisco Chronicle. Bloomberg News. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

...Two years later, the Welsh textile manufacturer Robert Owen attempted to establish the National Equitable Labour Exchange in London based on 'time money.' Both experiments failed, and a century later, economist John Pease Norton's proposal of an 'electric dollar' devolved into comedic fodder rather than a monetary innovation.

- ^ Wolf, Martin (December 3, 2019). "Best books of 2019: Economics". www.ft.com. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- ^ nytimes.com: "The Transformation of the American Dream", 4 Aug 2017

- ^ govtrack.us: "S. 811 (108th): American Dream Downpayment Act", 8 Apr 2003

External links

[edit]- Robert J. Shiller's website at Yale University Economics Department

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Robert J. Shiller on Nobelprize.org

- 1946 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American economists

- 21st-century American economists

- American economics writers

- American male non-fiction writers

- American Nobel laureates

- American people of Lithuanian descent

- Behavioral economists

- Behavioral finance

- Economists from Michigan

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Fellows of the Econometric Society

- American financial economists

- Kalamazoo College alumni

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology alumni

- Members of the American Philosophical Society

- National Bureau of Economic Research

- New Keynesian economists

- Nobel laureates in Economics

- Presidents of the American Economic Association

- University of Michigan alumni

- University of Minnesota faculty

- University of Pennsylvania faculty

- Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania faculty

- Writers from Detroit

- Yale School of Management faculty

- Yale Sterling Professors

- Yale University faculty