Syphilis

| Syphilis | |

|---|---|

| |

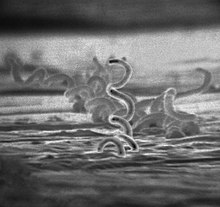

| Electron micrograph of Treponema pallidum | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Firm, painless, non-itchy skin ulcer[1] |

| Causes | Treponema pallidum usually spread by sex[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood tests, dark field microscopy of infected fluid[1][2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Many other diseases[1] |

| Prevention | Condoms, not having sex[1] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics[3] |

| Frequency | 45.4 million / 0.6% (2015)[4] |

| Deaths | 107,000 (2015)[5] |

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum.[3] The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, and tertiary).[1] The primary stage classically presents with a single chancre (a firm, painless, non-itchy skin ulceration) but there may be multiple sores.[1] In secondary syphilis, a diffuse rash occurs, which frequently involves the palms of the hands and soles of the feet.[1] There may also be sores in the mouth or vagina.[1] In latent syphilis, which can last for years, there are few or no symptoms.[1] In tertiary syphilis, there are gummas (soft, non-cancerous growths), neurological, or heart symptoms.[2] Syphilis has been known as "the great imitator" as it may cause symptoms similar to many other diseases.[1][2]

Syphilis is most commonly spread through sexual activity.[1] It may also be transmitted from mother to baby during pregnancy or at birth, resulting in congenital syphilis.[1][6] Other diseases caused by the Treponema bacteria include yaws (subspecies pertenue), pinta (subspecies carateum), and nonvenereal endemic syphilis (subspecies endemicum).[2] These three diseases are not typically sexually transmitted.[7] Diagnosis is usually made by using blood tests; the bacteria can also be detected using dark field microscopy.[1] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.) recommend all pregnant women be tested.[1]

The risk of sexual transmission of syphilis can be reduced by using a latex condom.[1] Syphilis can be effectively treated with antibiotics.[3] The preferred antibiotic for most cases is benzathine benzylpenicillin injected into a muscle.[3] In those who have a severe penicillin allergy, doxycycline or tetracycline may be used.[3] In those with neurosyphilis, intravenous benzylpenicillin or ceftriaxone is recommended.[3] During treatment people may develop fever, headache, and muscle pains, a reaction known as Jarisch-Herxheimer.[3]

In 2015, about 45.4 million people were infected with syphilis,[4] with 6 million new cases.[8] During 2015, it caused about 107,000 deaths, down from 202,000 in 1990.[5][9] After decreasing dramatically with the availability of penicillin in the 1940s, rates of infection have increased since the turn of the millennium in many countries, often in combination with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).[2][10] This is believed to be partly due to increased promiscuity, prostitution, decreasing use of condoms, and unsafe sexual practices among men who have sex with men.[11][12][13] In 2015, Cuba became the first country in the world to eliminate mother-to-child transmission of syphilis.[14]

Signs and symptoms

Syphilis can present in one of four different stages: primary, secondary, latent, and tertiary,[2] and may also occur congenitally.[15] It was referred to as "the great imitator" by Sir William Osler due to its varied presentations.[2][16]

Primary

Primary syphilis is typically acquired by direct sexual contact with the infectious lesions of another person.[17] Approximately 3 to 90 days after the initial exposure (average 21 days) a skin lesion, called a chancre, appears at the point of contact. This is classically (40% of the time) a single, firm, painless, non-itchy skin ulceration with a clean base and sharp borders approximately 0.3–3.0 cm in size.[2] The lesion may take on almost any form. In the classic form, it evolves from a macule to a papule and finally to an erosion or ulcer.[18] Occasionally, multiple lesions may be present (~40%),[2] with multiple lesions being more common when coinfected with HIV. Lesions may be painful or tender (30%), and they may occur in places other than the genitals (2–7%). The most common location in women is the cervix (44%), the penis in heterosexual men (99%), and anally and rectally in men who have sex with men (34%).[18] Lymph node enlargement frequently (80%) occurs around the area of infection,[2] occurring seven to 10 days after chancre formation.[18] The lesion may persist for three to six weeks if left untreated.[2]

Secondary

Secondary syphilis occurs approximately four to ten weeks after the primary infection.[2] While secondary disease is known for the many different ways it can manifest, symptoms most commonly involve the skin, mucous membranes, and lymph nodes.[19] There may be a symmetrical, reddish-pink, non-itchy rash on the trunk and extremities, including the palms and soles.[2][20] The rash may become maculopapular or pustular. It may form flat, broad, whitish, wart-like lesions on mucous membranes, known as condyloma latum. All of these lesions harbor bacteria and are infectious. Other symptoms may include fever, sore throat, malaise, weight loss, hair loss, and headache.[2] Rare manifestations include liver inflammation, kidney disease, joint inflammation, periostitis, inflammation of the optic nerve, uveitis, and interstitial keratitis.[2][21] The acute symptoms usually resolve after three to six weeks;[21] about 25% of people may present with a recurrence of secondary symptoms. Many people who present with secondary syphilis (40–85% of women, 20–65% of men) do not report previously having had the classical chancre of primary syphilis.[19]

Latent

Latent syphilis is defined as having serologic proof of infection without symptoms of disease.[17] It is further described as either early (less than 1 year after secondary syphilis) or late (more than 1 year after secondary syphilis) in the United States.[21] The United Kingdom uses a cut-off of two years for early and late latent syphilis.[18] Early latent syphilis may have a relapse of symptoms. Late latent syphilis is asymptomatic, and not as contagious as early latent syphilis.[21]

Tertiary

Tertiary syphilis may occur approximately 3 to 15 years after the initial infection, and may be divided into three different forms: gummatous syphilis (15%), late neurosyphilis (6.5%), and cardiovascular syphilis (10%).[2][21] Without treatment, a third of infected people develop tertiary disease.[21] People with tertiary syphilis are not infectious.[2]

Gummatous syphilis or late benign syphilis usually occurs 1 to 46 years after the initial infection, with an average of 15 years. This stage is characterized by the formation of chronic gummas, which are soft, tumor-like balls of inflammation which may vary considerably in size. They typically affect the skin, bone, and liver, but can occur anywhere.[2]

Neurosyphilis refers to an infection involving the central nervous system. It may occur early, being either asymptomatic or in the form of syphilitic meningitis, or late as meningovascular syphilis, general paresis, or tabes dorsalis, which is associated with poor balance and lightning pains in the lower extremities. Late neurosyphilis typically occurs 4 to 25 years after the initial infection. Meningovascular syphilis typically presents with apathy and seizures, and general paresis with dementia and tabes dorsalis.[2] Also, there may be Argyll Robertson pupils, which are bilateral small pupils that constrict when the person focuses on near objects (accommodation reflex) but do not constrict when exposed to bright light (pupillary reflex).

Cardiovascular syphilis usually occurs 10–30 years after the initial infection. The most common complication is syphilitic aortitis, which may result in aortic aneurysm formation.[2]

Congenital

Congenital syphilis is that which is transmitted during pregnancy or during birth. Two-thirds of syphilitic infants are born without symptoms. Common symptoms that develop over the first couple of years of life include enlargement of the liver and spleen (70%), rash (70%), fever (40%), neurosyphilis (20%), and lung inflammation (20%). If untreated, late congenital syphilis may occur in 40%, including saddle nose deformation, Higoumenakis sign, saber shin, or Clutton's joints among others.[6] Infection during pregnancy is also associated with miscarriage.[22]

Cause

Bacteriology

Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum is a spiral-shaped, Gram-negative, highly mobile bacterium.[10][18] Three other human diseases are caused by related Treponema pallidum subspecies, including yaws (subspecies pertenue), pinta (subspecies carateum) and bejel (subspecies endemicum).[2] Unlike subspecies pallidum, they do not cause neurological disease.[6] Humans are the only known natural reservoir for subspecies pallidum.[15] It is unable to survive more than a few days without a host. This is due to its small genome (1.14Mbp) failing to encode the metabolic pathways necessary to make most of its macronutrients. It has a slow doubling time of greater than 30 hours.[18]

Transmission

Syphilis is transmitted primarily by sexual contact or during pregnancy from a mother to her fetus; the spirochete is able to pass through intact mucous membranes or compromised skin.[2][15] It is thus transmissible by kissing near a lesion, as well as oral, vaginal, and anal sex.[2] Approximately 30% to 60% of those exposed to primary or secondary syphilis will get the disease.[21] Its infectivity is exemplified by the fact that an individual inoculated with only 57 organisms has a 50% chance of being infected.[18] Most (60%) of new cases in the United States occur in men who have sex with men. Syphilis can be transmitted by blood products, but the risk is low due to screening of donated blood in many countries. The risk of transmission from sharing needles appears limited.[2]

It is not generally possible to contract syphilis through toilet seats, daily activities, hot tubs, or sharing eating utensils or clothing.[23] This is mainly because the bacteria die very quickly outside of the body, making transmission by objects extremely difficult.[24]

Diagnosis

Syphilis is difficult to diagnose clinically during early infection.[18] Confirmation is either via blood tests or direct visual inspection using dark field microscopy. Blood tests are more commonly used, as they are easier to perform.[2] Diagnostic tests are unable to distinguish between the stages of the disease.[25]

Blood tests

Blood tests are divided into nontreponemal and treponemal tests.[18]

Nontreponemal tests are used initially, and include venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) tests. False positives on the nontreponemal tests can occur with some viral infections, such as varicella (chickenpox) and measles. False positives can also occur with lymphoma, tuberculosis, malaria, endocarditis, connective tissue disease, and pregnancy.[17]

Because of the possibility of false positives with nontreponemal tests, confirmation is required with a treponemal test, such as treponemal pallidum particle agglutination (TPHA) or fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test (FTA-Abs).[2] Treponemal antibody tests usually become positive two to five weeks after the initial infection.[18] Neurosyphilis is diagnosed by finding high numbers of leukocytes (predominately lymphocytes) and high protein levels in the cerebrospinal fluid in the setting of a known syphilis infection.[2][17]

Direct testing

Dark field microscopy of serous fluid from a chancre may be used to make an immediate diagnosis. Hospitals do not always have equipment or experienced staff members, and testing must be done within 10 minutes of acquiring the sample. Sensitivity has been reported to be nearly 80%; therefore the test can only be used to confirm a diagnosis, but not to rule one out. Two other tests can be carried out on a sample from the chancre: direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests. DFA uses antibodies tagged with fluorescein, which attach to specific syphilis proteins, while PCR uses techniques to detect the presence of specific syphilis genes. These tests are not as time-sensitive, as they do not require living bacteria to make the diagnosis.[18]

Prevention

Vaccine

As of 2018[update], there is no vaccine effective for prevention.[15] Several vaccines based on treponemal proteins reduce lesion development in an animal model but research continues.[26]

Sex

Condom use reduces the likelihood of transmission during sex, but does not completely eliminate the risk.[27] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) states, "Correct and consistent use of latex condoms can reduce the risk of syphilis only when the infected area or site of potential exposure is protected. However, a syphilis sore outside of the area covered by a latex condom can still allow transmission, so caution should be exercised even when using a condom."[28]

Abstinence from intimate physical contact with an infected person is effective at reducing the transmission of syphilis. The CDC states, "The surest way to avoid transmission of sexually transmitted diseases, including syphilis, is to abstain from sexual contact or to be in a long-term mutually monogamous relationship with a partner who has been tested and is known to be uninfected."[28]

Congenital disease

Congenital syphilis in the newborn can be prevented by screening mothers during early pregnancy and treating those who are infected.[30] The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) strongly recommends universal screening of all pregnant women,[31] while the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends all women be tested at their first antenatal visit and again in the third trimester. If they are positive, it is recommend their partners also be treated.[32] Congenital syphilis is still common in the developing world, as many women do not receive antenatal care at all, and the antenatal care others receive does not include screening. It still occasionally occurs in the developed world, as those most likely to acquire syphilis are least likely to receive care during pregnancy.[30] Several measures to increase access to testing appear effective at reducing rates of congenital syphilis in low- to middle-income countries.[32] Point-of-care testing to detect syphilis appeared to be reliable although more research is needed to assess its effectiveness and into improving outcomes in mothers and babies.[33]

Screening

The CDC recommends that sexually active men who have sex with men be tested at least yearly.[34] The USPSTF also recommends screening among those at high risk.[35]

Syphilis is a notifiable disease in many countries, including Canada[36] the European Union,[37] and the United States.[38] This means health care providers are required to notify public health authorities, which will then ideally provide partner notification to the person's partners.[39] Physicians may also encourage patients to send their partners to seek care.[40] Several strategies have been found to improve follow-up for STI testing, including email and text messaging of reminders for appointments.[41]

Treatment

Early infections

The first-line treatment for uncomplicated syphilis remains a single dose of intramuscular benzathine benzylpenicillin.[42] Doxycycline and tetracycline are alternative choices for those allergic to penicillin; due to the risk of birth defects, these are not recommended for pregnant women.[42] Resistance to macrolides, rifampicin, and clindamycin is often present.[15] Ceftriaxone, a third-generation cephalosporin antibiotic, may be as effective as penicillin-based treatment.[2] It is recommended that a treated person avoid sex until the sores are healed.[23]

Late infections

For neurosyphilis, due to the poor penetration of benzathine penicillin into the central nervous system, those affected are given large doses of intravenous penicillin for a minimum of 10 days.[2][15] If a person is allergic to penicillin, ceftriaxone may be used or penicillin desensitization attempted. Other late presentations may be treated with once-weekly intramuscular benzathine penicillin for three weeks. Treatment at this stage solely limits further progression of the disease and has a limited effect on damage which has already occurred.[2]

Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction

One of the potential side effects of treatment is the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. It frequently starts within one hour and lasts for 24 hours, with symptoms of fever, muscle pains, headache, and a fast heart rate.[2] It is caused by cytokines released by the immune system in response to lipoproteins released from rupturing syphilis bacteria.[43]

Pregnancy

Penicillin is an effective treatment for syphilis in pregnancy[44] but there is no agreement on which dose or route of delivery is most effective.[45] More research is needed.[45]

Epidemiology

| no data <35 35–70 70–105 105–140 140–175 175–210 | 210–245 245–280 280–315 315–350 350–500 >500 |

In 2012, about 0.5% of adults were infected with syphilis, with 6 million new cases.[8] In 1999, it is believed to have infected 12 million additional people, with greater than 90% of cases in the developing world.[15] It affects between 700,000 and 1.6 million pregnancies a year, resulting in spontaneous abortions, stillbirths, and congenital syphilis.[6] During 2015, it caused about 107,000 deaths, down from 202,000 in 1990.[5][9] In sub-Saharan Africa, syphilis contributes to approximately 20% of perinatal deaths.[6] Rates are proportionally higher among intravenous drug users, those who are infected with HIV, and men who have sex with men.[11][12][13] In the United States, rates of syphilis as of 2007 were six times greater in men than in women; they were nearly equal ten years earlier.[47] African Americans accounted for almost half of all cases in 2010.[48] As of 2014, syphilis infections continue to increase in the United States.[49]

Syphilis was very common in Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries.[10] Flaubert found it universal among nineteenth-century Egyptian prostitutes.[50] In the developed world during the early 20th century, infections declined rapidly with the widespread use of antibiotics, until the 1980s and 1990s.[10] Since 2000, rates of syphilis have been increasing in the US, Canada, the UK, Australia and Europe, primarily among men who have sex with men.[15] Rates of syphilis among US women have remained stable during this time, while rates among UK women have increased, but at a rate less than that of men.[51] Increased rates among heterosexuals have occurred in China and Russia since the 1990s.[15] This has been attributed to unsafe sexual practices, such as sexual promiscuity, prostitution, and decreasing use of barrier protection.[15][51][52]

Left untreated, it has a mortality rate of 8% to 58%, with a greater death rate among males.[2] The symptoms of syphilis have become less severe over the 19th and 20th centuries, in part due to widespread availability of effective treatment, and partly due to virulence of the bacteria.[19] With early treatment, few complications result.[18] Syphilis increases the risk of HIV transmission by two to five times, and coinfection is common (30–60% in some urban centers).[2][15] In 2015, Cuba became the first country in the world to eradicate mother to child transmission of syphilis.[14]

History

The exact origin of syphilis is disputed.[2] Syphilis was definitely present in the Americas before European contact,[54] and it may have been carried from the Americas to Europe by the returning crewmen from Christopher Columbus's voyage to the Americas; or it may have existed in Europe previously, but went unrecognized until shortly after Columbus returned. These are the Columbian and pre-Columbian hypotheses, respectively, with the Columbian hypothesis best supported by available evidence.[25][55][56]

The first written records of an outbreak of syphilis in Europe occurred in 1494 or 1495 in Naples, Italy, during a French invasion (Italian War of 1494–98).[10][25] Since it was claimed to have been spread by French troops, it was initially called the "French disease" by the people of Naples.[57] In 1530, the pastoral name "syphilis" (the name of a character) was first used by the Italian physician and poet Girolamo Fracastoro as the title of his Latin poem in dactylic hexameter describing the ravages of the disease in Italy.[58][59] It was also called the "Great Pox".[60][61]

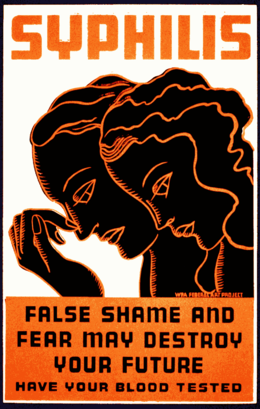

In the 16th through 19th centuries, syphilis was one of the largest public health burdens in prevalence, symptoms, and disability,[62]: 208–209 [63] although records of its true prevalence were generally not kept because of the fearsome and sordid status of sexually transmitted diseases in those centuries.[62]: 208–209 At the time the causative agent was unknown but it was well known that it was spread sexually and also often from mother to child. Its association with sex, especially sexual promiscuity and prostitution, made it an object of fear and revulsion and a taboo. The magnitude of its morbidity and mortality in those centuries reflected that, unlike today, there was no adequate understanding of its pathogenesis and no truly effective treatments. Its damage was caused not so much by great sickness or death early in the course of the disease but rather by its gruesome effects decades after infection as it progressed to neurosyphilis with tabes dorsalis.

The causative organism, Treponema pallidum, was first identified by Fritz Schaudinn and Erich Hoffmann, in 1905.[64][10] The first effective treatment for syphilis was Salvarsan, developed in 1910 by Paul Ehrlich. The effectiveness of treatment with penicillin was confirmed in trials in 1943.[10][60]

Before the discovery and use of antibiotics in the mid-twentieth century, mercury and isolation were commonly used, with treatments often worse than the disease.[60] During the 20th century, as both microbiology and pharmacology advanced greatly, syphilis, like many other infectious diseases, became more of a manageable burden than a scary and disfiguring mystery, at least in developed countries among those people who could afford to pay for timely diagnosis and treatment.

Many famous historical figures, including Franz Schubert, Arthur Schopenhauer, Édouard Manet,[10] Charles Baudelaire,[65] and Guy de Maupassant are believed to have had the disease.[66] Friedrich Nietzsche was long believed to have gone mad as a result of tertiary syphilis, but that diagnosis has recently come into question.[67]

Arts and literature

The earliest known depiction of an individual with syphilis is Albrecht Dürer's Syphilitic Man, a woodcut believed to represent a Landsknecht, a Northern European mercenary.[68] The myth of the femme fatale or "poison women" of the 19th century is believed to be partly derived from the devastation of syphilis, with classic examples in literature including John Keats' La Belle Dame sans Merci.[69][70]

The artist Jan van der Straet painted Preparation and Use of Guayaco for Treating Syphilis, a scene of a wealthy man receiving treatment for syphilis with the tropical wood guaiacum sometime around 1580.[71]

Tuskegee and Guatemala studies

One of the most infamous United States cases of questionable medical ethics in the 20th century was the Tuskegee syphilis study.[72] The study took place in Tuskegee, Alabama, and was supported by the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) in partnership with the Tuskegee Institute.[73] The study began in 1932, when syphilis was a widespread problem and there was no safe and effective treatment.[16] The study was designed to measure the progression of untreated syphilis. By 1947, penicillin had been shown to be an effective cure for early syphilis and was becoming widely used to treat the disease.[73] Its use in later syphilis was still unclear.[16] Despite this, study directors continued the study and did not offer the participants treatment with penicillin.[73] Some have found that penicillin ended up being given to many of the subjects regardless (28% by 1952 compared to 33% of the controls).[16]

In the 1960s, Peter Buxtun sent a letter to the CDC, who controlled the study, expressing concern about the ethics of letting hundreds of black men die of a disease that could be cured. The CDC asserted that it needed to continue the study until all of the men had died. In 1972, Buxton went to the mainstream press, causing a public outcry. As a result, the program was terminated, the U.S. Government settled a class action lawsuit on behalf of study participants and their descendants in the amount of $10 million ($61.8 million in 2023) and agreed to provide free medical treatment to surviving participants and family members infected as a consequence of the study, and Congress created a commission empowered to write regulations to deter such abuses from occurring in the future.[73]

On 16 May 1997, thanks to the efforts of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study Legacy Committee formed in 1994, survivors of the study were invited to the White House to be present when President Bill Clinton apologized on behalf of the United States government for the study.[74]

Syphilis experiments were also carried out in Guatemala from 1946 to 1948. They were US-sponsored human experiments, conducted during the government of Juan José Arévalo with the cooperation of some Guatemalan health ministries and officials. Doctors infected soldiers, prisoners, and mental patients with syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases, without the informed consent of the subjects, and then treated them with antibiotics. In October 2010, the US formally apologized to Guatemala for conducting these experiments.[75]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Syphilis - CDC Fact Sheet (Detailed)". CDC. 2 November 2015. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah Kent ME, Romanelli F (February 2008). "Reexamining syphilis: an update on epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and management". Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 42 (2): 226–36. doi:10.1345/aph.1K086. PMID 18212261.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Syphilis". CDC. 4 June 2015. Archived from the original on 21 February 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

{{cite journal}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

{{cite journal}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Woods CR (June 2009). "Congenital syphilis-persisting pestilence". Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 28 (6): 536–7. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3181ac8a69. PMID 19483520.

- ^ "Pinta". NORD. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ a b Newman, L; Rowley, J; Vander Hoorn, S; Wijesooriya, NS; Unemo, M; Low, N; Stevens, G; Gottlieb, S; Kiarie, J; Temmerman, M (2015). "Global Estimates of the Prevalence and Incidence of Four Curable Sexually Transmitted Infections in 2012 Based on Systematic Review and Global Reporting". PLOS ONE. 10 (12): e0143304. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143304. PMC 4672879. PMID 26646541.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Lozano, R (15 December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMID 23245604.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Franzen, C (December 2008). "Syphilis in composers and musicians--Mozart, Beethoven, Paganini, Schubert, Schumann, Smetana". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 27 (12): 1151–7. doi:10.1007/s10096-008-0571-x. PMID 18592279.

- ^ a b Coffin, L. S.; Newberry, A.; Hagan, H.; Cleland, C. M.; Des Jarlais, D. C.; Perlman, D. C. (January 2010). "Syphilis in Drug Users in Low and Middle Income Countries". The International journal on drug policy. 21 (1): 20–7. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.02.008. PMC 2790553. PMID 19361976.

- ^ a b Gao, L; Zhang, L; Jin, Q (September 2009). "Meta-analysis: prevalence of HIV infection and syphilis among MSM in China". Sexually transmitted infections. 85 (5): 354–8. doi:10.1136/sti.2008.034702. PMID 19351623.

- ^ a b Karp, G; Schlaeffer, F; Jotkowitz, A; Riesenberg, K (January 2009). "Syphilis and HIV co-infection". European Journal of Internal Medicine. 20 (1): 9–13. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2008.04.002. PMID 19237085.

- ^ a b "WHO validates elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis in Cuba". WHO. 30 June 2015. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Stamm, LV (February 2010). "Global challenge of antibiotic-resistant Treponema pallidum". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 54 (2): 583–9. doi:10.1128/aac.01095-09. PMC 2812177. PMID 19805553.

- ^ a b c d White, RM (13 March 2000). "Unraveling the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis". Archives of Internal Medicine. 160 (5): 585–98. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.5.585. PMID 10724044.

- ^ a b c d Committee on Infectious Diseases (2006). Larry K. Pickering (ed.). Red book 2006 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases (27th ed.). Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics. pp. 631–44. ISBN 978-1-58110-207-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Eccleston, K; Collins, L; Higgins, SP (March 2008). "Primary syphilis". International journal of STD & AIDS. 19 (3): 145–51. doi:10.1258/ijsa.2007.007258. PMID 18397550.

- ^ a b c Mullooly, C; Higgins, SP (August 2010). "Secondary syphilis: the classical triad of skin rash, mucosal ulceration and lymphadenopathy". International journal of STD & AIDS. 21 (8): 537–45. doi:10.1258/ijsa.2010.010243. PMID 20975084.

- ^ Dylewski J, Duong M (2 January 2007). "The rash of secondary syphilis". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 176 (1): 33–5. doi:10.1503/cmaj.060665. PMC 1764588. PMID 17200385.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bhatti MT (2007). "Optic neuropathy from viruses and spirochetes". Int Ophthalmol Clin. 47 (4): 37–66, ix. doi:10.1097/IIO.0b013e318157202d. PMID 18049280.

- ^ Cunningham, F, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Spong CY, Dashe JS, Hoffman BL, Casey BM, Sheffield JS (2013). "Abortion". Williams Obstetrics. McGraw-Hill. p. 5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Syphilis & MSM (Men Who Have Sex With Men) - CDC Fact Sheet". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 16 September 2010. Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ G. W. Csonka (1990). Sexually transmitted diseases: a textbook of genitourinary medicine. Baillière Tindall. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-7020-1258-7. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Farhi, D; Dupin, N (September–October 2010). "Origins of syphilis and management in the immunocompetent patient: facts and controversies". Clinics in Dermatology. 28 (5): 533–8. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2010.03.011. PMID 20797514.

- ^ Cameron, CE; Lukehart, SA (20 March 2014). "Current status of syphilis vaccine development: need, challenges, prospects". Vaccine. 32 (14): 1602–9. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.09.053. PMC 3951677. PMID 24135571.

- ^ Koss CA, Dunne EF, Warner L (July 2009). "A systematic review of epidemiologic studies assessing condom use and risk of syphilis". Sex Transm Dis. 36 (7): 401–5. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181a396eb. PMID 19455075.

- ^ a b "Syphilis - CDC Fact Sheet". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 16 September 2010. Archived from the original on 16 September 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "A young man, J. Kay, afflicted with a rodent disease which has eaten away part of his face. Oil painting, ca. 1820". wellcomelibrary.org. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Schmid, G (June 2004). "Economic and programmatic aspects of congenital syphilis prevention". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 82 (6): 402–9. PMC 2622861. PMID 15356931.

- ^ U.S. Preventive Services Task, Force (19 May 2009). "Screening for syphilis infection in pregnancy: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 150 (10): 705–9. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-150-10-200905190-00008. PMID 19451577.

- ^ a b Hawkes, S; Matin, N; Broutet, N; Low, N (15 June 2011). "Effectiveness of interventions to improve screening for syphilis in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 11 (9): 684–91. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70104-9. PMID 21683653.

- ^ Shahrook, S; Mori, R; Ochirbat, T; Gomi, H (29 October 2014). "Strategies of testing for syphilis during pregnancy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10: CD010385. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010385.pub2. PMID 25352226.

- ^ "Trends in Sexually Transmitted Diseases in the United States: 2009 National Data for Gonorrhea, Chlamydia and Syphilis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 22 November 2010. Archived from the original on 4 August 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bibbins-Domingo, Kirsten; Grossman, David C.; Curry, Susan J.; Davidson, Karina W.; Epling, John W.; García, Francisco A. R.; Gillman, Matthew W.; Harper, Diane M.; Kemper, Alex R.; Krist, Alex H.; Kurth, Ann E.; Landefeld, C. Seth; Mangione, Carol M.; Phillips, William R.; Phipps, Maureen G.; Pignone, Michael P. (7 June 2016). "Screening for Syphilis Infection in Nonpregnant Adults and Adolescents". JAMA. 315 (21): 2321–7. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.5824. PMID 27272583.

- ^ "National Notifiable Diseases". Public Health Agency of Canada. 5 April 2005. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Viñals-Iglesias, H; Chimenos-Küstner, E (1 September 2009). "The reappearance of a forgotten disease in the oral cavity: syphilis". Medicina oral, patologia oral y cirugia bucal. 14 (9): e416–20. PMID 19415060.

- ^ "Table 6.5. Infectious Diseases Designated as Notifiable at the National Level-United States, 2009 [a]". Red Book. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Brunner & Suddarth's textbook of medical-surgical nursing (12th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2010. p. 2144. ISBN 978-0-7817-8589-1. Archived from the original on 18 May 2016.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hogben, M (1 April 2007). "Partner notification for sexually transmitted diseases". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 44 Suppl 3: S160–74. doi:10.1086/511429. PMID 17342669.

- ^ Desai, Monica; Woodhall, Sarah C; Nardone, Anthony; Burns, Fiona; Mercey, Danielle; Gilson, Richard (2015). "Active recall to increase HIV and STI testing: a systematic review". Sexually Transmitted Infections: sextrans-2014-051930. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2014-051930. ISSN 1368-4973.

- ^ a b Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). "Syphilis-CDC fact sheet". CDC. Archived from the original on 25 February 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Radolf, JD; Lukehart SA (editors) (2006). Pathogenic Treponema: Molecular and Cellular Biology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 1-904455-10-7.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Alexander, JM; Sheffield, JS; Sanchez, PJ; Mayfield, J; Wendel GD, Jr (January 1999). "Efficacy of treatment for syphilis in pregnancy". Obstetrics and gynecology. 93 (1): 5–8. doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00338-x. PMID 9916946.

- ^ a b Walker, GJ (2001). "Antibiotics for syphilis diagnosed during pregnancy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD001143. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001143. PMID 11686978.

- ^ "Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization (WHO). 2004. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Trends in Reportable Sexually Transmitted Diseases in the United States, 2007". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 13 January 2009. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "STD Trends in the United States: 2010 National Data for Gonorrhea, Chlamydia, and Syphilis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 22 November 2010. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Clement, Meredith E.; Okeke, N. Lance; Hicks, Charles B. (2014). "Treatment of Syphilis". JAMA. 312 (18): 1905. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.13259. ISSN 0098-7484.

- ^ Francis Steegmuller (1979). Flaubert in Egypt, A Sensibility on Tour. ISBN 9780897330183.

- ^ a b Kent, ME; Romanelli, F (February 2008). "Reexamining syphilis: an update on epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and management". Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 42 (2): 226–36. doi:10.1345/aph.1K086. PMID 18212261.

- ^ Ficarra, G; Carlos, R (September 2009). "Syphilis: The Renaissance of an Old Disease with Oral Implications". Head and neck pathology. 3 (3): 195–206. doi:10.1007/s12105-009-0127-0. PMC 2811633. PMID 20596972.

- ^ The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Summer 2007, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Armelagos, George J. (2012), "The Science behind Pre-Columbian Evidence of Syphilis in Europe: Research by Documentary", Evol. Anthropol., 21 (2): 50–7, doi:10.1002/evan.20340, PMC 3413456, PMID 22499439

- ^ Rothschild, BM (15 May 2005). "History of syphilis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 40 (10): 1454–63. doi:10.1086/429626. PMID 15844068.

- ^ Harper, KN; Zuckerman, MK; Harper, ML; Kingston, JD; Armelagos, GJ (2011). "The origin and antiquity of syphilis revisited: an appraisal of Old World pre-Columbian evidence for treponemal infection". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 146 Suppl 53: 99–133. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21613. PMID 22101689.

- ^ Winters, Adam (2006). Syphilis. New York: Rosen Pub. Group. p. 17. ISBN 9781404209060.

- ^ Dormandy, Thomas (2006). The worst of evils: man's fight against pain: a history (Uncorrected page proof. ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0300113228.

- ^ Anthony Grafton (March 1995). "Drugs and Diseases: New World Biology and Old World Learning". New Worlds, Ancient Texts The Power of Tradition and the Shock of Discovery. Harvard University Press. pp. 159–194. ISBN 9780674618763.

- ^ a b c Dayan, L; Ooi, C (October 2005). "Syphilis treatment: old and new". Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 6 (13): 2271–80. doi:10.1517/14656566.6.13.2271. PMID 16218887.

- ^ Knell, RJ (7 May 2004). "Syphilis in renaissance Europe: rapid evolution of an introduced sexually transmitted disease?" (PDF). Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 271 Suppl 4 (Suppl 4): S174–6. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2003.0131. PMC 1810019. PMID 15252975. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 August 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b de Kruif, Paul (1932). "Ch. 7: Schaudinn: The Pale Horror". Men Against Death. New York: Harcourt, Brace. OCLC 11210642.

- ^ Rayment, Michael; Sullivan, Ann K; et al. (2011), ""He who knows syphilis knows medicine"—the return of an old friend", British Journal of Cardiology, 18: 56–58,

"He who knows syphilis knows medicine" said Father of Modern Medicine, Sir William Osler, at the turn of the 20th Century. So common was syphilis in days gone by, all physicians were attuned to its myriad clinical presentations. Indeed, the 19th century saw the development of an entire medical subspecialty – syphilology – devoted to the study of the great imitator, Treponema pallidum.

- ^ Schaudinn, Fritz Richard; Hoffmann, Erich (1905). "Vorläufiger Bericht über das Vorkommen von Spirochaeten in syphilitischen Krankheitsprodukten und bei Papillomen" [Preliminary report on the occurrence of Spirochaetes in syphilitic chancres and papillomas]. Arbeiten aus dem Kaiserlichen Gesundheitsamte. 22. Berlin: Verlag von Julius Springer: 527–534.

- ^ Hayden, Deborah (2008). Pox: Genius, Madness, and the Mysteries of Syphilis. Basic Books. p. 113. ISBN 0786724137.

- ^ Halioua, Bruno (30 June 2003). "Comment la syphilis emporta Maupassant | La Revue du Praticien". www.larevuedupraticien.fr. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bernd, Magnus. "Nietzsche, Friedrich". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Eisler, CT (Winter 2009). "Who is Dürer's "Syphilitic Man"?". Perspectives in biology and medicine. 52 (1): 48–60. doi:10.1353/pbm.0.0065. PMID 19168944.

- ^ Hughes, Robert (2007). Things I didn't know: a memoir (1st Vintage Book ed.). New York: Vintage. p. 346. ISBN 978-0-307-38598-7.

- ^ Wilson, [ed]: Joanne Entwistle, Elizabeth (2005). Body dressing ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Oxford: Berg Publishers. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-85973-444-5.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Reid, Basil A. (2009). Myths and realities of Caribbean history ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-8173-5534-0. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Katz RV; Kegeles SS; Kressin NR; et al. (November 2006). "The Tuskegee Legacy Project: Willingness of Minorities to Participate in Biomedical Research". J Health Care Poor Underserved. 17 (4): 698–715. doi:10.1353/hpu.2006.0126. PMC 1780164. PMID 17242525.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d "U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 15 June 2011. Archived from the original on 28 May 2010. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Study: President Bill Clinton's Apology". University of Virginia Health Sciences Library. Archived from the original on 30 December 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "U.S. apologizes for newly revealed syphilis experiments done in Guatemala". The Washington Post. 1 October 2010. Archived from the original on 15 October 2010. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

The United States revealed on Friday that the government conducted medical experiments in the 1940s in which doctors infected soldiers, prisoners and mental patients in Guatemala with syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)