Taharqa

| Taharqa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Granite sphinx of Taharqa from Kawa in Sudan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 690–664 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Shabaka | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Tantamani | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Great Queen Takahatenamun, Atakhebasken, Naparaye, Tabekenamun[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Amenirdis II, Ushankhuru, Nesishutefnut | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Piye | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Abar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 664 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | 25th dynasty | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Taharqa, also spelled Taharka or Taharqo (Biblical Tirhaka or Tirhaqa, Manetho's Tarakos, Strabo's Tearco), was a pharaoh of ancient Egypt of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty and qore (king) of the Kingdom of Kush.

Early life

Taharqa was the son of Piye, the Nubian king of Napata who had first conquered Egypt. Taharqa was also the cousin and successor of Shebitku.[3] The successful campaigns of Piye and Shabaka paved the way for a prosperous reign by Taharqa.

Ruling period

Taharqa's reign can be dated from 690 BC to 664 BC.[4] Evidence for the dates of his reign is derived from the Serapeum stela, catalog number 192. This stela records that an Apis bull born and installed (fourth month of Peret, day 9) in Year 26 of Taharqa died in Year 20 of Psammetichus I (4th month of Shomu, day 20), having lived 21 years. This would give Taharqa a reign of 26 years and a fraction, in 690–664 BC.[5]

Irregular accession to power

Taharqa explicitly states in Kawa Stela V, line 15, that he succeeded his predecessor (generally assumed to be Shebitku but now established to be Shabaka instead) after the latter's death with this statement: "I received the Crown in Memphis after the Falcon flew to heaven."[6] The reference to Shebitku was an attempt by Taharqa to legitimise his accession to power.[7] However, Taharqa never mentions the identity of the royal falcon and completely omits any mention of Shabaka's intervening reign between Shebitku and Taharqa possibly because he ousted Shabaka from power.[8]

In Kawa IV, line 7-13, Taharqa states: “He (Taharqa) sailed northward to Thebes amongst the beautiful young people that His Majesty, the late King Shabataqo/Shebitku, had sent from Nubia. He was there (in Thebes) with him. He appreciated him more than any of his brothers. (There here follows a description of the [poor] state of the temple of Kawa as observed by the prince). The heart of his Majesty was in sadness about it until his Majesty became king, crowned as King of Upper and Lower Egypt (...). It was during the first year of his reign he remembered what he had seen of the temple when he was young”.[9]

In Kawa V: line 15, Taharqa states “I was brought from Nubia amongst the royal brothers that his Majesty had brought. As I was with him, he liked me more than all his brothers and all his children, so that he distinguished me. I won the heart of the nobles and was loved by all. It was only after the hawk had flown to heaven that I received the crown in Memphis.”[10]

Therefore, Taharqa says that King Shebitku, who was very fond of him, brought him with him to Egypt and during that trip he had the opportunity to see the deplorable state of the temple of Amun at Kawa, an event he remembered after becoming king. But on Kawa V Taharqa says that sometime after his arrival in Egypt under a different king whom this time he chose not to name, there occurred the death of this monarch (Shabaka here) and then his own accession to the throne occurred. Taharqa's evasiveness on the identity of his predecessor suggests that he assumed power in an irregular fashion and chose to legitimise his kingship by conveniently stating the possible fact or propaganda that Shebitku favoured him "more than all his brothers and all his children."[11]

Moreover, in lines 13 – 14 of Kawa stela V, His Majesty (who can be none other but Shebitku), is mentioned twice, and at first sight the falcon or hawk that flew to heaven, mentioned in the very next line 15, seems to be identical with His Majesty referred to directly before (i.e. Shebitku).[12] However, in the critical line 15 which recorded Taharqa's accession to power, a new stage of the narrative begins, separated from the previous one by a period of many years, and the king or hawk/falcon that flew to heaven is conspicuously left unnamed in order to distinguish him from His Majesty, Shebitku. Moreover, the purpose of Kawa V, was to describe several separate events that occurred at distinct stages of Taharqa’s life, instead of telling a continuous story about it.[13] Therefore, the Kawa V text began with the 6th year of Taharqa and referred to the High Nile flood of that year before abruptly jumping back to Taharqa's youth at the end of line 13.[14] In the beginning of line 15, Taharqa's coronation is mentioned (with the identity of the hawk/falcon—now known to be Shabaka—left unnamed but if it was Shebitku, Taharqa's favourite king, Taharqa would clearly have identified him) and there is a description given of the extent of the lands and foreign countries under Egypt's control but then (in the middle of line 16) the narrative switches abruptly back again to Taharqa's youth: "My mother was in Ta-Sety …. Now I was far from her as a twenty year old recruit, as I went with His Majesty to the North Land".[15] However, immediately afterwards (around the middle of line 17) the text jumps forward again to the time of Taharqa's accession: "Then she came sailing downstream to see me after a long period of years. She found me after I had appeared on the throne of Horus...".[16] Hence, the Kawa V narrative switches from one event to another, and has little to no chronological coherence or value.

Reign

Taharqa's reign was initially a prosperous renaissance period in Egypt and Kush. During this period of peace and prosperity, the empire flourished. In the sixth year of Taharqa's reign, prosperity was also aided by abundant rainfall and a large harvest. Taharqa took full advantage of the lull in fighting and abundant harvest. He restored existing temples, built new ones, and built the largest pyramid in the Napatan region of Nubia. Particularly impressive were his additions to the Temple at Karnak, new temple at Kawa, and temple at Jebel Barkal.[17][18][19][20][21]

Taharqa eventually came into conflict with the Neo-Assyrian Empire (935-605 BC) which controlled a vast empire stretching from the Caucasus to the Arabian peninsula, and from Cyprus to Persia. In 701 BC Taharqa sent a force to aid a rebellion by Judah and Phoenicia against Assyrian rule, however his army was defeated at Ekron and driven back into Egypt. Sennacherib then besieged Jerusalem. However its king Ezekiah, encouraged by his prophet Isiah and with moral support from Taharqa, refused to open the gates. The Assyrians agreed to withdraw and spare Jerusalem in a compromise that saw Ezekiah and Judah agree to pay heavy tribute to Assyria. Sennacherib was thus able to advance his territory as far as Pelusium, thirty miles east of what is today the Suez canal.

The Biblical account in the Second Book of Kings of Sennacherib's army being ravaged by the Angel of the Lord whilst besieging Jerusalem or attempting to invade Egypt is considered controversial and lacking in historicity, with Assyriologist and historian Georges Roux pointing out that it is rejected by most modern scholars.

Biblical references

Scholars[who?] have identified Taharqa with Tirhakah, king of Ethiopia (Kush), who waged war against Sennacherib during the reign of King Hezekiah of Judah (2 Kings 19:9; Isaiah 37:9).

The events in the Biblical account are believed to have taken place in 701 BC, whereas Taharqa came to the throne some ten years later. A number of explanations have been proposed: one being that the title of king in the Biblical text refers to his future royal title, when at the time of this account he was likely only a military commander.

Herodotus, the Greek historian who wrote his Histories c. 450 BC, speaks of a divinely-appointed disaster destroying an army of Sennacherib, which was defeated by Sethos after praying to the gods. The gods sent "a multitude of field-mice, which devoured all the quivers and bowstrings of the enemy, and ate the thongs by which they managed their shields."[22] This is commemorated in "a stone statue of Sethos, with a mouse in his hand, and an inscription to this effect 'Look on me, and learn to reverence the gods'."

According to Francis Llewellyn Griffith, an attractive hypothesis is to identify the Pharaoh as Taharqa before his succession, and Sethos as his Memphitic priestly title, "supposing that he was then governor of Lower Egypt and high-priest of Ptah, and that in his office of governor he prepared to move on the defensive against a threatened attack by Sennacherib. While Taharqa was still in the neighbourhood of Pelusium, some unexpected disaster may have befallen the Assyrian host on the borders of Palestine and arrested their march on Egypt."[23]

The two snakes in the crown of pharaoh Taharqa show that he was the king of both the lands of Egypt and Nubia.

Assyrian conquest of Egypt

It was during his reign that Egypt's enemy Assyria at last invaded Egypt. Esarhaddon led several successful campaigns against Taharqa, which he recorded on several monuments. His first attack in 679 BC, pacified Arab tribes around the Sinai and led him as far as the Brook of Egypt where he took the city of Arzani (Wadi al Arish). Esarhaddon then proceeded to invade Egypt proper in Taharqa's 17th regnal year, after Esarhaddon had settled various revolts; among the Israelites at Ashkelon and Phoenicians at Tyre. In 671 BC the Assyrian king crossed the Sinai in a 15 day march and entered Egypt, conquering the vast land with surprising speed, and captured and sacked Memphis, where he captured numerous members of the royal family and forced Taharqa to flee back to his Nubian homeland[24].

Esarhaddon's annals describe the invasion and conquest vividly; From the town of Ishupri as far as Memphis, his royal residence a fifteen days march, I fought daily, without interruption, very bloody battles against Taharqa, king of Egypt and Ethiopia, the one accursed by all the great gods. Five times I hit him with the point of my arrows, inflicting wounds from which he shall not recover, and then I laid siege to Memphis, his royal residence, and conquered it in only half a day, by means of mines, breaches and assault ladders. His queen, the women of his palace, Ushanahuru, his heir, his other children, his possessions, his horses, large and small livestock beyond counting I carried away as booty to Assyria. All Ethiopians (read Nubians) I deported from Egypt, leaving not even one to pay homage to me. Everywhere in Egypt I appointed local kings, governors and administrators.

Taharqa fled to Nubia, and Esarhaddon reorganized the political structure in Egypt, establishing the native Egyptian Necho I as his subject king at Sais. Upon Esarhaddon's return to Assyria he erected a stele alongside the previous Egyptian and Assyrian Commemorative stela of Nahr el-Kalb, as well as a victory stele at Zincirli Höyük, showing Taharqa's son, prince Ushankhuru in bondage.

Two years after the Assyrian king's departure, however, Taharqa intrigued in the affairs of Egypt, and fanned numerous revolts managing to retake the city of Memphis from the native Egyptian princes acting on behalf of the Assyrian king. Esarhaddon died in the Assyrian city of Harran en route to quell the revolt, and it was left to his son and heir Ashurbanipal (668-627 BC) to once again invade Egypt.

Ashurbanipal sent a small army into southern Egypt, which retook Memphis and defeated Taharqa on the plains south of the city, who afterwards fled to Thebes. The Assyrians set out to chase him from there too, however a revolt broke out amongst the native princes of the Nile Delta, delaying the Assyrian advance. Taharqa was forced to flee to Nubia, where he died.

Death

Taharqa died in the city of Thebes[25] in 664 BC and was followed by his appointed successor Tantamani, a son of Shabaka. Taharqa was buried at Nuri, in North Sudan.[26]

Depictions

Taharqa was erroneously described by the Ancient Greek historian Strabo as having "Advanced as far as Europe",[27] and (citing Megasthenes), even as far as the Pillars of Hercules in Spain,[28].

In biblical depictions, he is the saviour of the Hebrew people, as they are being besieged by Sennacherib (Isaiah 37:8-9, & 2 Kings 19:8-9).

Actor Will Smith was developing a film entitled The Last Pharaoh, which he planned to produce and star as Taharqa. Carl Franklin contributed to the script.[29] Randall Wallace was hired to rewrite in September 2008.[30]

Image gallery

-

Serpentine weight of 10 daric. Inscribed for Taharqa in the midst of Sais. 25th Dynasty. From Egypt, probably from Nesaft. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

-

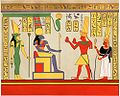

Taharqa offering wine jars to Falcon-god Hemen

-

Taharqa as a sphinx

-

Taharqa close-up

-

Taharqa with Queen Takahatamun at Gebel Barkal.

-

Shabti of King Taharqa

-

Chapel of Taharqa and Shepenwepet

-

Taharqa before the god Amun in Gebel Barkal (Sudan), in temple B300

-

Taharqa followed by his mother Queen Abar. Gebel Barkal - room C.

See also

- Victory stele of Esarhaddon

- Statues of Amun in the form of a ram protecting King Taharqa

- Sphinx of Taharqo

References

- ^ Clayton, Peter A. Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. p.190. 2006. ISBN 0-500-28628-0

- ^ Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05128-3., pp.234-6

- ^ Toby Wilkinson, The Thames and Hudson Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson, 2005. p.237

- ^ K.A. Kitchen, The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100–650 BC), 3rd edition, 1996, Aris & Phillips Ltd,pp.380-391

- ^ Kitchen, p.161

- ^ Kitchen, p.167

- ^ F. Payraudeau, Retour sur la succession Shabaqo-Shabataqo, Nehet 1, 2014, p. 115-127 online here

- ^ F. Payraudeau, Retour sur la succession Shabaqo-Shabataqo, Nehet 1, 2014,p.122-123

- ^ [52 – JWIS III 132-135; FHN I, number 21, 135-144.]

- ^ [53 – JWIS III 135-138; FHN I, number 22, 145-158.]

- ^ F. Payraudeau, Retour sur la succession Shabaqo-Shabataqo, Nehet 1, 2014, p. 115-127 online here

- ^ G.P.F. Broekman, The order of succession between Shabaka and Shabataka. A different view on the chronology of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, GM 245, (2015), p.29

- ^ Broekman, GM 245 (2015), p.29

- ^ Broekman, GM 245 (2015), p.29

- ^ Broekman, GM 245 (2015), p.29

- ^ Broekman, GM 245 (2015), p.29

- ^ Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 219–221. ISBN 1-55652-072-7.

- ^ Bonnet, Charles (2006). The Nubian Pharaohs. New York: The American University in Cairo Press. pp. 142–154. ISBN 978-977-416-010-3.

- ^ Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. pp. 161–163. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- ^ Emberling, Geoff (2011). Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa. New York: Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-0-615-48102-9.

- ^ Silverman, David (1997). Ancient Egypt. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 0-19-521270-3.

- ^ Herodotus (2003). The HIstories. London, England: Penguin Books. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-14-044908-2.

- ^ F.L. Griffith, Stories of the High Priests of Memphis: The Sethon of Herodotus and the Demotic Tales of Khamuas (1900), p. 11

- ^ Georges Roux - Ancient Iraq pp327-328

- ^ Historical Prism inscription of Ashurbanipal I by Arthur Carl Piepkorn page 36. Published by University of Chicago Press [1]

- ^ Why did Taharqa build his tomb at Nuri? Conference of Nubian Studies

- ^ Strabo (2006). Geography. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 7. ISBN 0-674-99266-0.

- ^ Snowden, Before Color Prejudice: The Ancient View of Blacks. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1983, p.52

- ^ Jim Slotek, Kevin Williamson (2008-03-23). "Will Smith set to conquer Egypt?". Jam Showbiz. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- ^ Michael Fleming (2008-09-08). "Will Smith puts on 'Pharaoh' hat". Variety. Retrieved 2008-09-08.

Further reading

- Robert Morkot, The Black Pharaohs: Egypt's Nubian Rulers, The Rubicon Press, 2000. ISBN 0-948695-23-4