Vepsians

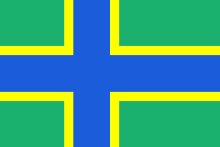

Flag of Vepsians | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 5,936 (2010)[1] | |

| 281 (2001)[2] | |

| 54 (2011)[3] | |

| 8 (2009)[4] | |

| Languages | |

| Russian, Vepsian | |

| Religion | |

| Russian Orthodoxy | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Finnic peoples | |

Veps or Vepsians are a Finnic people who speak the Veps language, which belongs to the Finnic branch of the Uralic languages. The self-designations of these people in various dialects are vepslaine, bepslaane, and (in northern dialects, southwest of Lake Onega) lüdinik and lüdilaine. According to the 2002 census, there were 8,240 Veps in Russia. Of the 281 Veps in Ukraine, 11 spoke Vepsian (Ukr. Census 2001). The most prominent researcher of the Veps in Finland is Eugene Holman.[5] Western Vepsians have kept their language and culture. Nowadays almost all Vepsians speak fluent Russian. The young generation in general does not speak their native language.

Geography

In modern times, they live in the area between Lake Ladoga, Onega, and Lake Beloye - in the Russian Republic of Karelia in the former Veps National Volost, in Leningrad Oblast along the Oyat River in the Podporozhsky and Lodeynopolsky Districts and further south in the Tikhvinsky and Boksitogorsky Districts, and in Vologda oblast in the Vytegorsky and Babayevsky Districts.[6]

History

Prehistory

Archeological and linguistic studies suggest that Vepsians lived in the valleys of the Sheksna, the Suda, and the Syas rivers, developing, according to Kalevi Wiik, from the proto-Vepsian Kargopol culture to the east of Lake Onega. They probably also lived in East Karelia and on the northern coast of Lake Onega. It is possible that the earliest mention of the Veps dates to the sixth century CE, when the Gothic historian Jordanes mentioned a people called Vasina broncas, which may have indicated the Vepsians.[7] One of the eastern routes of the Vikings went through their area, and the bjarm people mentioned by the Vikings as inhabiting the coast of the White Sea may have referred to the Veps.[8] Evidence from tombs prove that they had contact with Staraya Ladoga, Finland and Meryans, other Volga Finnic tribes and later with the Principality of Novgorod and other Russian states. Later Vepsians inhabited also the western and eastern shores of Onega.

Historical period

In early Kievan Rus' chronicles, they are called "Весь" (Ves’) and in some Arabic sources they are called Wisu. It is assumed that Bjarmians were at least partly Vepsians. From the 12th century their history is connected with first the Principality of Novgorod and then Muscovy. Russian settlement reached the Onega Veps in the 14th or 15th century.[9] Eastern Vepsians in the Kargopol area merged linguistically with the Russians before the 20th century.

The existence of the Vepsian people was not widely known until the mid-19th century. Despite its close relationship to the Karelian and the Finnish languages, the Vepsian language was thus one of the last Uralic languages to be recognized as one.

Vepsians numbered 25,607 in 1897. Some 7,300 of them inhabited East Karelia. In the beginning of the 20th century there were some signs of national awakening among Vepsians. Early Soviet nationality politics supported this progress, and 24 administrative units with the status of national village soviets were formed. The alphabet and the written language were developed. Teachers started to instruct in Vepsian in some elementary schools. The Soviet authorities started to oppress the Vepsian culture in 1937. All national activities were stopped and the national districts were abolished. When Finland invaded East Karelia in the Continuation war, some Vepsians joined the so-called Kindred Battalion of the Finnish Army. These troops were relinquished to the Soviet Union after the war.[9][10][11]

In the postwar period many Veps moved from their historic villages to larger cities. In 1983, on the initiative of national academics, an inquiry was carried out which showed that there were nearly 13,000 Veps in the Soviet Union, 5,600 of whom lived in Karelia, 4,000 in the Leningrad region and just under a 1,000 in the Vologda region.[9] The new Vepsian primer Abekirj and other elementary school books were published in Petrozavodsk in 1991. Kodima, a newspaper in Vepsian, has been published since 1993. The Vepsian rural commune was formed in East Karelia in 1994, encompassing 8,200 square kilometers of land and 3,373 inhabitants, 42% of them Vepsian. The republican authorities granted some budgetary autonomy to the commune in 1996. The language was taught as a subject in two schools, the Shyoltozero and Rybreka. However, the cultural revival slowed down in the second half of the 1990s and the federal authorities abolished the autonomy in 2006. Nowadays the young generation in general does not speak the language.[11]

Notable Vepsians

- Nikolay Abramov – Vepsian-language poet, translator and writer

Republic of Karelia, northwestern Russia.

Further reading

- Kurs, Ott (March 2001). "The Vepsians: An administratively divided nationality". Nationalities Papers. 29 (1): 69–83. doi:10.1080/00905990120036385.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|quotes=,|laydate=,|laysource=,|laysummary=, and|coauthors=(help)

References

- ^ Russian census 2010 Archived October 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ukrainian census 2001

- ^ Population of Estonia by ethnic nationality, mother tongue and citizenship

- ^ "Население по национальности и родному языку" [Population by nationality and mother language] (PDF). Перепись населения Республики Беларусь 2009 года (in Russian). Нацыянальны статыстычны камітэт Рэспублікі Беларусь. 12 August 2010.

- ^ http://www.eng.helsinki.fi/staff/holman.html

- ^ http://www.regard-est.com/home/breve_contenu.php?id=1070

- ^ Toivo Vuorela 1960, Suomensukuiset kansat, p. 103

- ^ Saressalo 2005, Vepsa Maa, Kansa, Kulttuuri, p. 13

- ^ a b c The Red Book of the Peoples of Russian Empire - The Veps

- ^ Ott Kurs (1994). "Vepsians: the easternmost Baltic-Finnic people". Terra. 107: 127–135.

- ^ a b Ott Kurs (2001). "The Vepsians: An administratively divided nationality". Nationalities Papers. 29: 69–83. doi:10.1080/00905990120036385.