Yellow Submarine (song)

| "Yellow Submarine" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

US picture sleeve | ||||

| Single by the Beatles | ||||

| from the album Revolver | ||||

| A-side | "Eleanor Rigby" (double A-side) | |||

| Released | 5 August 1966 | |||

| Recorded | 26 May and 1 June 1966 | |||

| Studio | EMI, London | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 2:38 | |||

| Label |

| |||

| Songwriter(s) | Lennon–McCartney | |||

| Producer(s) | George Martin | |||

| The Beatles singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "Yellow Submarine" on YouTube | ||||

"Yellow Submarine" is a song by the English rock band the Beatles from their 1966 album Revolver. It was also issued on a double A-side single, paired with "Eleanor Rigby". Written as a children's song by Paul McCartney and John Lennon, it was drummer Ringo Starr's vocal spot on the album. The single went to number one on charts in the United Kingdom and several other European countries, and in Australia, Canada and New Zealand. It won an Ivor Novello Award for the highest certified sales of any single written by a British songwriter and issued in the UK in 1966. In the US, the song peaked at number two on the Billboard Hot 100 chart.

The Beatles recorded "Yellow Submarine" during a period characterised by experimentation in the recording studio. After taping the basic track and vocals in late May 1966, they held a session to overdub nautical sound effects, party ambience and chorus singing, recalling producer George Martin's previous work with members of the Goons. As a novelty song coupled with "Eleanor Rigby", a track devoid of any rock instrumentation, the single marked a radical departure for the group. The song inspired the 1968 animated film Yellow Submarine and appeared as the opening track on the accompanying soundtrack album.

In the US, the release of "Yellow Submarine" coincided with the controversies surrounding Lennon's "More popular than Jesus" remarks – which led some radio stations to impose a ban on the Beatles' music – and the band's public opposition to the Vietnam War. The song received several social and political interpretations. It was adopted as an anti-authority statement by the counterculture during Vietnam War demonstrations and was also appropriated in strike action and other forms of protest. Some listeners viewed the song as a code for drugs, particularly the barbiturate Nembutal which was sold in yellow capsules, or as a symbol for escapism. "Yellow Submarine" has continued to be a children's favourite and has frequently been performed by Starr on his tours with the All Starr Band.

Authorship

[edit]When asked in May 1966 about his vocal spot on the Beatles' forthcoming album, Ringo Starr told an NME reporter, with reference to "Yellow Submarine": "John and Paul have written a song which they think is for me but if I mess it up then we might have to find another country-and-western song off somebody else's LP."[5] In a joint interview taped for use at the Ivor Novello Awards night in March 1967, McCartney and Lennon said that the song's melody was created by combining two different songs they had been working on separately.[6][7] Lennon recalled that McCartney brought in the chorus ("the submarine ... the chorus bit"), which Lennon suggested combining with a melody for the verses that he had already written.[7]

McCartney commented in 1966: "It's a happy place, that's all ... We were trying to write a children's song. That was the basic idea."[8] Their working manuscript for the lyrics shows a verse crossed out and an accompanying note from Lennon reading: "Disgusting!! See me."[9] Scottish singer Donovan contributed the line "Sky of blue and sea of green".[10]

In 1972, Lennon made the following statement about the song's authorship: "Both of us. Paul wrote the catchy chorus. I helped with the blunderbuss bit."[11]

In 1980, Lennon talked further about the song: "'Yellow Submarine' is Paul's baby. Donovan helped with the lyrics. I helped with the lyrics too. We virtually made the track come alive in the studio, but based on Paul's inspiration. Paul's idea. Paul's title ... written for Ringo."[8] In his 1997 authorised biography, Many Years from Now, McCartney recalled coming up with the initial idea while lying in bed, adding that "It was pretty much my song as I recall ... I think John helped out ... but the chorus, melody and verses are mine."[12]

Previewing the 2022 re-release of the Beatles' Revolver album, however, Rob Sheffield describes Lennon's home demo of the song as "a melancholy acoustic ballad, evoking Plastic Ono Band". He says this solo recording debunks the widely accepted view that "Yellow Submarine" was merely a McCartney children's song dashed out for Starr, and that it conveys a deeper emotional resonance than was previously apparent.[13]

Concept and composition

[edit]Author Steve Turner writes that in its focus on childhood themes, "Yellow Submarine" fitted with the contemporaneous psychedelic aesthetic, and that this outlook was reflected in George Harrison's comments to Maureen Cleave in his "How a Beatle Lives" interview, when he spoke of an individual's purity at birth and gradual corruption by society. Cleave likened his perspective to a contention put forward in William Wordsworth's poetry.[14] In Many Years from Now, McCartney says he "started making a story, sort of an ancient mariner, telling the young kids where he'd lived" and that the story line became gradually more obscure.[15][nb 1]

According to McCartney, the idea of a coloured submarine originated from his 1963 holiday in Greece, where he had enjoyed an iced spoon sweet that was yellow or red, depending on the flavour, and known locally as a submarine.[16] Lennon had also thought of an underwater craft when he and Harrison and their wives first took the hallucinogenic drug LSD in early 1965.[17][18] After the disorienting experience of visiting a London nightclub, they returned to Harrison's Surrey home, Kinfauns, where Lennon perceived the bungalow design as a submarine with him as the captain.[19][20][nb 2] Musicologists Russell Reising and Jim LeBlanc comment that the band's adoption of a coloured submarine as their vessel chimed with Cary Grant captaining a pink one in the 1959 comedy film Operation Petticoat, made during the height of his psychoanalytical experimentation with LSD.[22]

The Beatles' and psychedelia's adoption of childhood themes was also evident in the band's May 1966 single "Paperback Writer", as the falsetto backing vocals chant the title of the French nursery rhyme "Frère Jacques".[23] Starr later said he found "Yellow Submarine" a "really interesting" choice for his vocal spot, since his own songwriting at that point amounted to "rewriting Jerry Lee Lewis's songs".[24] In author Jonathan Gould's opinion, Starr's "guileless" persona ensured the song was presented with the same "deadpan quality" that he gave to the Beatles' feature films. As a result, Gould continues, the eponymous submarine "became a satirically updated version of the improbable craft in which Edward Lear put his characters to sea – the Owl and the Pussycat's pea-green boat, the Jumblies' unsinkable sieve".[25]

The song begins with the first verse, opening with the line "In the town where I was born". The structure comprises two verses and a chorus; a third verse, followed by a chorus; two further verses, the first of which is an instrumental passage; and repeated choruses.[26] In musicologist Alan Pollack's description, the melody is "painfully simple, though in a subtle way, bears the John Lennon stamp of pentatonicism". The composition uses just five chords; in Roman numeral analysis, these are I, ii, IV, V and vi.[26]

The lyrics offer an anti-materialist message typical of the Beatles' songs on Revolver and of psychedelic culture. Reising and LeBlanc view the song's lyrics as a celebration of "the simple pleasures of brotherhood, exotic adventure, and an appreciation of nature".[27] They also see "Yellow Submarine" as the band introducing travel-related imagery to align with a psychedelic journey conveyed in an LSD trip, a theme used more introspectively in "Tomorrow Never Knows", where Lennon exhorts the listener to "float downstream".[28][nb 3] Musicologist William Echard recognises the psychedelic traits of oceanic imagery, childhood and nostalgia as especially prominent in the song, thereby making "Yellow Submarine" one of the most obvious examples of UK psychedelia's preoccupation with a return to childhood.[29]

Recording

[edit]Main session

[edit]The Beatles began recording "Yellow Submarine" during the eighth week of the sessions for Revolver.[30] The project was characterised by the group's increased experimentation in the studio,[31] reflecting the division between their recording output and the music they made as live performers.[32][33] The first session for the song took place at EMI Studios (now Abbey Road Studios) on 26 May 1966, but without producer George Martin, who was unwell.[34] Author Ian MacDonald views Bob Dylan's contemporaneous hit single, "Rainy Day Women ♯12 & 35", as a possible inspiration on the Beatles.[35] The two songs share a similar marching rhythm[35] and a festive singalong quality.[5][36]

The band spent much of the afternoon and evening rehearsing the song.[37] They recorded four takes of the rhythm track, with Starr playing drums, Lennon on acoustic guitar, McCartney on bass, and Harrison on tambourine.[37] The performance was taped at a faster tempo than appears on the completed track, which is in the key of G♭ major.[38]

Following a reduction mix of take 4, Starr recorded his lead vocal[37] and he, Lennon, McCartney and Harrison sang vocals over the choruses.[9] The vocal parts were again treated with varispeed;[39] in this instance, they were recorded a semitone lower.[38] Harrison's contribution is especially prominent,[40] departing from his bandmates to sing an f1 note on the word "submarine".[41][nb 4] The recording was given another reduction mix, reducing the four tracks to two,[34] to allow for the inclusion of nautical and party-like sound effects.[43]

Sound effects overdubs

[edit]The Beatles dedicated their 1 June session to adding the song's sound effects.[44][45] For this, Martin drew on his experience as a producer of comedy records for Beyond the Fringe and members of the Goons.[46] The band invited guests to participate,[47] including Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones, Harrison's wife Pattie Boyd, Marianne Faithfull, Beatles road managers Mal Evans and Neil Aspinall,[44] and Alf Bicknell, the band's driver.[45] The studio store cupboard was sourced for items such as chains, bells, whistles, hooters, a tin bath and a cash till.[48][nb 5]

Although effects were added throughout the track, they were heavily edited for the released recording.[44] The sound of ocean waves enters at the start of the second verse and continues through the first chorus.[26] Harrison created this effect by swirling water around a bathtub.[43] On the third verse, a party atmosphere was evoked through a combination of Jones clinking glasses together and blowing an ocarina,[43] snatches of excited chatter,[49] Boyd's high-pitched shrieks, Bicknell rattling chains,[45] and tumbling coins.[34] To fill the two-bar gap following the line "And the band begins to play", Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick used a recording of a brass band from EMI's tape library.[50][51] They disguised the piece by splicing up the taped copy and rearranging the melody.[51][nb 6]

The recording includes a sound-effects solo over the non-singing verse,[49] designed to convey the submarine's operation.[26] Lennon blew through a straw into a pan of water to create a bubbling effect.[43] Other sounds imitate the whirring of machinery,[26] a ship's bell, hatches being slammed,[49] chains hitting metal,[43] and finally the submarine submerging.[52][nb 7] Lennon used the studio's echo chamber to shout out commands and responses[45] such as "Full speed ahead, Mr Boatswain."[53] From a hallway just outside the studio, Starr yelled: "Cut the cable!"[45] Gould describes the section as a "Goonish concerto" consisting of sound effects "drawn from the collective unconscious of a generation of schoolboys raised on films about the War Beneath the Seas".[49][nb 8] According to Echard, the effects are "an especially rich example of how sound effects can function topically" in psychedelia, since they serve a storytelling role and further the song's "naval and oceanic" narrative and its nostalgic qualities.[55] The latter, he says, is "due to their timbre, recalling radio broadcasts not only as a contemporary experience but also as an emblem of the near-distant past", and he also sees the effects as cinematic in their presentation as "a coherent sonic scenario, one that could be diegetic to an imagined series of filmic events".[29]

In the final verse, Lennon echoes Starr's lead vocal,[49] delivering the lines in a manner that musicologist Walter Everett terms "manic".[43] Keen to sound as if he were singing underwater, Lennon tried recording the part with a microphone encased in a condom and, at Emerick's suggestion, submerged inside a bottle filled with water.[56] This proved ineffective,[56] and Lennon instead sang with the microphone plugged into a Vox guitar amplifier.[43]

All the participants and available studio staff sang the closing choruses, augmenting the vocals recorded by the Beatles on 26 May.[43] Evans also played a marching bass drum over this section.[52] When the overdubs were finished, Evans led everybody in a line around the studio doing the conga dance while banging on the drum strapped to his chest.[48] Martin later told Alan Smith of the NME that the band "loved every minute" of the session and that it was "more like the things I've done with the Goons and Peter Sellers" than a typical Beatles recording.[57] Music critic Tim Riley characterises "Yellow Submarine" as "one big Spike Jones charade".[42]

Discarded intro

[edit]The song originally opened with a 15-second section containing narration by Starr and dialogue by Harrison, McCartney and Lennon, supported by the sound of marching feet (created by blocks of coal being shaken inside a box).[44][58] Written by Lennon,[58] the narrative focused on people marching from Land's End to John o' Groats, and "from Stepney to Utrecht", and sharing the vision of a yellow submarine.[44][nb 9]

The introduction is as follows: "...yellow submarine. And we will march till three the day to see them gathered there. From Land o' Groats to John o' Green[sic], with Stephney do we tread. To see his yellow submarine, we love it!"

Despite the time taken in developing and recording this intro, the band chose to discard the idea, and the section was cut from the track on 3 June.[60] Everett comments that the recording of "Yellow Submarine" took twice as much studio time as the band's debut album, Please Please Me.[43][nb 10]

Release

[edit]The Beatles chose to break with their previous policy by allowing album tracks to be issued on a UK single.[64][65] The "Yellow Submarine" single was the Beatles' thirteenth single release in the United Kingdom and the first to feature Starr as lead vocalist.[66] It was issued there on 5 August 1966 as a double A-side with "Eleanor Rigby", and in the United States on 8 August.[67] In both countries, Revolver was released on the same day as the single.[68][69] The pairing of a novelty song and a ballad devoid of any instrumentation played by a Beatle marked a considerable departure from the content of the band's previous singles.[70][71] Unusually for their post-1965 singles also, there were no promotional films made for either of the A-sides.[72]

According to a report in Melody Maker on 30 July, the reason for the Beatles breaking with precedent and releasing a single from Revolver was to thwart sales of cover recordings of "Eleanor Rigby".[73] When Harrison was asked for the reason, he replied that the group had decided to "put it out" rather than watch as "dozens" of other artists scored hits with the songs.[74] In his NME interview in August, Martin said:

I was keen that the track be released in some way apart from the album, but you have to realise that the Beatles aren't usually very happy about issuing material twice in this way. They feel that they might be cheating the public ... However, we got to thinking about it, and we realised that the fans aren't really being cheated at all. Most albums have only 12 tracks; the Beatles always do 14![57]

Commercial performance

[edit]Whether you loved it or hated it, the "Yellow Submarine", once lodged in the brain, was impossible to get rid of. Everywhere you went in the latter half of 1966, you could hear people whistling it.[70]

– Author Nicholas Schaffner

The single topped sales charts around the world.[75] The double A-side was number 1 on Record Retailer's chart (later adopted as the UK Singles Chart) for four weeks during a chart run of 13 weeks.[76] On Melody Maker's singles chart, it was number 1 for three weeks and then spent two weeks at number 2.[77] It was the band's twelfth consecutive chart-topping single in the UK.[78] Despite the double A-side status there, "Yellow Submarine" was the song recognised with the Ivor Novello Award for highest certified sales of any A-side in 1966.[6][nb 11]

In the US, the single's release coincided with the Beatles' final tour and, further to the controversy over the "butcher cover" originally used for the Capitol Records LP Yesterday and Today,[81][82] public furore over Lennon's "More popular than Jesus" remarks, originally published in the UK in his "How a Beatle Lives" interview with Cleave.[83][84] The "Jesus" controversy overshadowed the release of the single and the album there;[85] public bonfires were held to burn their records and memorabilia,[86][87] and many radio stations refused to play the Beatles' music.[88] The group were also vocal in their opposition to the Vietnam War, a stand that further redefined their public image in the US.[89] Capitol were wary of the religious references in "Eleanor Rigby", given the ongoing controversy, and instead promoted "Yellow Submarine" as the lead side.[49][90] The song peaked at number 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 (behind "You Can't Hurry Love" by the Supremes)[91] and number 1 on the charts compiled by Cash Box[92] and Record World.[93]

In Gould's description, it was "the first 'designated' Beatles single since 1963" not to top the Billboard Hot 100, a result he attributes to Capitol's caution in initially overlooking "Eleanor Rigby".[94] During the US tour, Beatles press officer Tony Barrow asked Leroy Aarons of The Washington Post to remove mention of the band's "latest" single slipping on the charts when Aarons presented his article for their approval.[95][nb 12] In author Robert Rodriguez's view, the radio bans were responsible for the song's failure to top the chart.[97] The single sold 1,200,000 copies in four weeks[97] and, on 12 September, earned the Beatles their twenty-first US Gold Record award, a total they had achieved in just over two-and-a-half years.[98]

Critical reception

[edit]One of the UK's older pop journalists, Allen Evans of the NME expressed confusion at the Beatles' progressiveness on Revolver[99] but predicted, "One thing seems certain ... you'll soon all be singing about a 'Yellow Submarine'."[100] Derek Johnson echoed this in his review of the single for the same publication, and described the song as "so different from the usual Beatles, and a compulsive sing-along".[101] Melody Maker's reviewer said that the song's basic qualities would make it a "nursery rhyme or public house singalong" and complimented Starr's vocal performance and the "fooling around" behind him.[102] Billboard characterised it as the Beatles' "most unusual easy rocker to date" due to the Starr lead vocal and an arrangement that featured "everything ... but the kitchen sink".[103] Cash Box found the single's pairing "unique" and described "Yellow Submarine" as "a thumping, happy go lucky, special effects filled, highly improbable tale of joyous going on beneath the sea".[104] Record World said that "The Beatles are out for a whacking good time on this jolly nonsense song sparked by all sorts of sideshow sounds."[105]

In their joint review for Record Mirror, Peter Jones said he was not especially impressed by the track but that it demonstrated the band's versatility, while Richard Green wrote: "Sort of Beatle 'Puff the Magic Dragon' ... Will be very big at about 9.30 on a Saturday morning on the Light Programme."[106] Reporting from London for The Village Voice, Richard Goldstein stated that Revolver was ubiquitous around the city, as if Londoners were uniting behind the Beatles in response to the antagonism shown towards the band in the US. He said that "Yellow Submarine" depicted an "undersea utopia" and was "as whimsical and childlike as its flip side ['Eleanor Rigby'] is metaphysical".[107] In her album review for The Evening Standard, Maureen Cleave wrote that "Ringo has the cheeriest song" and predicted that "it will have all the Americans at his feet once again."[108]

Ray Davies of the Kinks derided "Yellow Submarine" when invited to give a rundown of Revolver in Disc and Music Echo.[109] He dismissed it as "a load of rubbish"[110] and a bad choice for a single, adding that "I take the mickey out of myself on the piano and play stuff like this."[111] Writing in the recently launched Crawdaddy!, Paul Williams was also highly critical, saying the song was as poor as Sgt. Barry Sadler's pro-military novelty single "Ballad of the Green Berets".[112][nb 13]

["Yellow Submarine"] was acclaimed as the best kiddie-toon since Mel Blanc's "I T'ought I T'aw a Puddytat". Ringo yodelled it while John clanged bells and made absurd U-boat noises. It seems ridiculous now – it seemed ridiculous then – but it sold well ...[114]

– Roy Carr and Tony Tyler, The Beatles: An Illustrated Record, 1978

In his review of the Beatles' final concert, held at Candlestick Park near San Francisco on 29 August,[115] Phil Elwood of the San Francisco Examiner rued that the band had failed to play anything from their "new, delightful album" in concert, particularly "Yellow Submarine".[116] In her round-up of the year's pop music for The Evening Standard, Cleave named the single and Revolver as the best records of 1966.[117] Writing in his 1977 book The Beatles Forever, Nicholas Schaffner described "Yellow Submarine" as "the most flippant and outrageous piece the Beatles would ever produce".[70]

Tim Riley views "Yellow Submarine" as the first original Beatles composition on which Starr was able to project his personality, and he admires Lennon's vocal contribution for its abundance of "Goon humor" and for transforming the track into a "sailor's drinking song".[118] Ian MacDonald calls it "a sparkling novelty song impossible to dislike".[35] By contrast, Thomas Ward of AllMusic says it interrupts the "consistent brilliance" of Revolver and while highly effective as a children's song, "after a few listens, it becomes tiresome, just as happens with many of McCartney's other 'fun' songs (such as 'When I'm Sixty Four')."[119] Alex Petridis of The Guardian views "Yellow Submarine" as "lovable but slight" and considers it "faintly mind-boggling" that the Beatles chose the song as the lead side of their first single culled from an album over not just "Eleanor Rigby" but also "Taxman" and "Here, There and Everywhere".[65]

Interpretations

[edit]

"Yellow Submarine" received various social and political interpretations in the 1960s. Music journalist Peter Doggett describes it as a "culturally empty" song that nevertheless "became a kind of Rorschach test for radical minds".[120] The chorus was appropriated by students, sports fans and striking workers in their own chants. Doggett cites student protests at Berkeley in late 1966 where demonstrators taunted university authorities and protested against the Vietnam War, using endless choruses of "Yellow Submarine" at the close of each event to state their ongoing determination and emphasise the ideological division.[121][nb 14] Sociologist and cultural commentator Todd Gitlin recalled that the song thereby became an anthem uniting the counterculture and New Left activism at Berkeley, citing its adoption by Michael Rossman of the Free Speech Movement,[122] who described it as an expression of "our trust in our future, and of our longing for a place fit for us all to live in".[123]

A writer for the P.O. Frisco commented in 1966, "the Yellow Submarine may suggest, in the context of the Beatles' anti-Vietnam War statement in Tokyo this year, that the society over which Old Glory floats is as isolated and morally irresponsible as a nuclear submarine."[124] At a Mobe protest, also in San Francisco, a yellow papier-mâché submarine made its way through the crowd, which Time magazine interpreted as a "symbol of the psychedelic set's desire for escape".[120] Writer and activist LeRoi Jones read the song as a reflection of white American society's exclusivity and removal from reality, saying, "The Beatles can sing 'We all live in a yellow submarine' because that is literally where they, and all their people (would like to), live. In the solipsistic pink and white nightmare of 'the special life' ..."[120]

Donovan later said that "Yellow Submarine" represented the Beatles' predicament as prisoners of their international fame, to which they reacted by singing an uplifting, communal song.[125] In November 1966, artist Alan Aldridge created a cartoon illustration of "Yellow Submarine" and three other Revolver tracks to accompany a feature article on the Beatles in Woman's Mirror magazine. The illustration depicted the submarine as a large boot with the captain peering out from the top. The article, which drew from Maureen Cleave's interviews with the band members from early in the year, was flagged on the cover in a painting by Aldridge that showed the Beatles ensnared by barbed wire under a giant speech balloon reading: "HELP!"[126]

In Rossman's adoption of the song's message, it represented a way of thinking introduced by the Beatles, who "taught us a new style of song", after which, "The Yellow Submarine ... was launched by hip pacifists in a New York harbor, and then led a peace parade of 10,000 down a New York street."[123][nb 15] The theme of friendship and community in "Yellow Submarine" also resonated with the ideology behind the 1967 Summer of Love.[128] Derek Taylor, the Beatles' former press officer who worked as a music publicist in Los Angeles in the mid 1960s, recalled it as "a kind of ark ... a Yellow Submarine is a symbol for some kind of vessel which would take us all to safety ... the message in that thing is that good can prevail over evil."[129][nb 16]

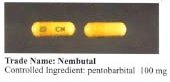

The song was also viewed as a code for drugs, at a time when it became common for fans to scrutinise the Beatles' lyrics for alternative meanings.[131][132] "Yellow Submarine" was adopted by the counterculture as a song promoting the barbiturate Nembutal,[133] which was nicknamed a yellow submarine for the colour and shape of its capsule.[134] Some listeners interpreted the title as a reference to a marijuana joint stained by resin,[90][135] while the lyrics' description of a voyage of discovery resonated with the idea of a psychedelic trip.[134][nb 17] Writing for Esquire in December 1967, Robert Christgau felt that the Beatles "want their meanings to be absorbed on an instinctual level" and dismissed such interpretations, saying: "I can't believe that the Beatles indulge in the simplistic kind of symbolism that turns a yellow submarine into a Nembutal or a banana – it is just a yellow submarine, damn it, an obvious elaboration of John [Lennon]'s submarine fixation, first revealed in A Hard Day's Night."[137][nb 18]

Legacy

[edit]The song inspired the 1968 United Artists animated film Yellow Submarine, which was produced by King Features Syndicate, the company behind the popular children's TV series The Beatles.[139][140] King Features' Al Brodax first approached McCartney about making the film with a story outline based on "Yellow Submarine".[141][nb 19] Doggett writes that the song thereby became the most important track on Revolver "in business terms", since it staved off pressure from United Artists for the Beatles to fulfil their contractual obligations for a third feature film.[143] The band's 1966 recording was the opening track on the accompanying soundtrack album, which closed with an orchestral reprise[144] arranged by Martin, titled "Yellow Submarine in Pepperland".[145][nb 20]

The Yellow Submarine film inspired a wealth of licensed products,[149] including a Corgi Toys die-cast replica of the titular vessel.[150] In 1984, a 51-foot (16 m)-long metal sculpture, built by apprentices from the Cammell Laird shipyard and titled Yellow Submarine, was used as part of Liverpool's International Garden Festival.[151] In 2005, it was placed outside Liverpool's John Lennon Airport,[152] in preparation for the city's year as the European Capital of Culture in 2008.[151] Tying in with the restoration and re-release of the animated film in 1999, the United States Postal Service issued a "Yellow Submarine" postage stamp and Eurostar ran an 18-carriage train transformed into a submarine with visuals from the film on its London–Paris service.[153]

Music journalist Rob Chapman writes that "Yellow Submarine" inaugurated a trend for nursery rhyme-like songs during the psychedelic era, peaking in late 1967 with UK top-ten singles for Keith West, Traffic and Simon Dupree and the Big Sound.[154] Nicholas Schaffner recognised the track as an exception within the music-industry phenomenon of novelty songs, which were traditionally gimmicky recordings by one-hit wonders, since the Beatles were the most popular stars of the era and achieved one of the most commercially successful novelty hits of all time.[155] By the early 2000s, according to music journalist Charles Shaar Murray, "Yellow Submarine" was a "perennial children's favourite".[156] Rolling Stone's editors describe it as "the gateway drug that turns little children into Beatle fans".[46][nb 21]

The tune of the song has been used in protests and demonstrations in Britain and America, with the lyrics changed to "We all live in a fascist regime". It was adopted in this way by protesters in New York City during George Bush's inauguration as US president in January 2005;[158] by anti-G8 protesters in Scotland in July the same year;[159] by anti-monarchist demonstrators in London on the day of Prince William and Kate Middleton's wedding in April 2011;[160] and by Londoners protesting the result of the UK general election in May 2015.[161][nb 22]

Starr reprised the song's nautical and escapist themes in his 1969 composition "Octopus's Garden", his second and last song recorded by the Beatles.[163][164] "Yellow Submarine" has continued to be one of his signature songs during his post-Beatles solo career.[165] He has regularly included it in his concert set lists when touring with the All Starr Band. The first of several live versions appears on the 1992 album Ringo Starr and His All Starr Band Volume 2: Live from Montreux.[152] For McCartney, "Yellow Submarine" inaugurated a strand of his writing that became highly popular among generations of children yet was also open to mockery by his detractors.[166] Later examples of his children's songs include "All Together Now" from Yellow Submarine;[167] Wings' "Mary Had a Little Lamb",[168] based on the nursery rhyme of that title;[169] and "We All Stand Together", from McCartney's 1984 animated short film Rupert and the Frog Song.[170]

The Beatles' recording was included on compilation albums such as 1962–1966 and 1.[152] In 1986, "Yellow Submarine" / "Eleanor Rigby" was reissued in the UK as part of EMI's twentieth anniversary of each of the Beatles' singles and peaked at number 63 on the UK Singles Chart.[171] The 2015 edition of 1 and the expanded 1+ box set includes a video clip for the song, compiled from footage from the 1968 animated film.[172] In July 2018, the two songs were released on a 7-inch vinyl picture disc to mark the 50th anniversary of the Yellow Submarine film's release.[173]

Spanish football club Villarreal CF got the nickname "Yellow Submarine" from the same song of the Beatles, and since then have become synonymously connected to the La Liga club. At the time, the song was highly popular in Spain during 1960s (albeit it was sung in Spanish), when Villarreal was still a small club.[174]

Personnel

[edit]According to Ian MacDonald[35] and Walter Everett,[38] except where noted:

The Beatles

- Ringo Starr – lead and backing vocals, drums, shouting

- John Lennon – acoustic guitar, backing vocals, sound effects (bubbles), shouting

- Paul McCartney – bass guitar, backing vocals, shouting

- George Harrison – tambourine, backing vocals, sound effects (waves)

Additional contributors

- Neil Aspinall – backing vocals

- Alf Bicknell – sound effects (rattling chains),[45] backing vocals

- Pattie Boyd – laughter,[45] backing vocals

- Mal Evans – bass drum, backing vocals

- Marianne Faithfull – backing vocals

- Brian Jones – sound effects (clinking glasses), ocarina, backing vocals

- George Martin – backing vocals

- Geoff Emerick – tape loop (marching band),[50] backing vocals

- John Skinner, Terry Condon – sound effects (chains in bathtub)[44]

Charts and certifications

[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

Certifications and sales[edit]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

[edit]- ^ Referring to Lennon's home demo, producer Giles Martin likens "Yellow Submarine" to a Woody Guthrie song, while Sheffield calls it "a heart-wrenching childhood memory ballad, halfway between 'Julia' and 'Strawberry Fields Forever'". Lennon's lyrics include the lines "In the place where I was born / No one cared, no one cared / And the name that I was born / No one cared, no one cared."[13]

- ^ While commenting on the effect LSD soon had on the band's music, author and musician John Kruth describes Harrison and Lennon's introduction to the drug as a "maiden voyage into the unknown".[21]

- ^ In this way, according to the authors, "Yellow Submarine" anticipated similar themes in other artists' work and in Beatles songs such as "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" (with its reference to "newspaper taxis"), "Magical Mystery Tour" and "Across the Universe".[28]

- ^ Music critic Tim Riley describes the note as "an unresolved sixth" and an example of the Beatles' "taut vocal arrangement".[42] Walter Everett views it as an example of Harrison indulging "his penchant for nonresolving nonchord tones".[41]

- ^ The same till was used on Pink Floyd's 1973 song "Money".[48]

- ^ Martin said the piece was most likely "Le Rêve Passe", a 1906 composition by Georges Krier and Charles Helmer.[35]

- ^ According to EMI employee John Skinner, he and his colleague Terry Condon swirled chains inside the metal bathtub during the session.[44]

- ^ Harrison later cited the "comic aspect" of this portion of the song as an example of the Beatles' instinctively drawing from their earliest memories of listening to music, even if it was "schmaltz" and other records they disliked.[54]

- ^ This spoken prologue referenced British engineer Barbara Moore's 1960 walk along the length of the UK, from the extreme southern point of mainland England to the extreme northern point of mainland Scotland.[59][41]

- ^ "Yellow Submarine" was remixed with the introduction restored for the song's inclusion on the "Real Love" CD single,[51][61] released in 1996 as part of the Beatles' Anthology project.[62] This remix also gave more prominence to the effects than the edit used in 1966.[41][63]

- ^ At that time, the Ivor Novellos focused only on contributions to the British music industry.[79] The Official Charts Company recognises Tom Jones's "Green, Green Grass of Home", written by American songwriter Curly Putman, as the best-selling single of 1966 in the UK.[80]

- ^ Turner comments that Aarons could have been referring to "Paperback Writer", whose chart descent was unsurprising by mid August, or to "Yellow Submarine", which "wasn't slipping down, but neither was it racing up".[96]

- ^ Adding to the band's failing image in the US media, a Pittsburgh disc jockey broadcast an interview in May 1966 in which the Beatles ridiculed Sadler's song and his support of the Vietnam War.[113]

- ^ Among other examples of the song's adoption by radical groups, students at the London School of Economics boasted, "We all live in a red LSE"; striking workers in the UK complained, "We all live on bread and margarine"; and Sing Out! magazine, in its anti-Vietnam War adaptation of the lyrics, rewrote the chorus as "We're all dropping jellied gasoline".[120]

- ^ An initiative of the Workshop in Non-Violence, the 6-foot-long craft was launched into the Hudson River filled with messages of goodwill, hope and desperation addressed to "all people in the world". Harrison and Starr wore the Workshop's pin emblem – containing a yellow submarine and a peace symbol – at the press launch for Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band in May 1967.[127]

- ^ American Beat poet Allen Ginsberg played "Yellow Submarine", along with "Eleanor Rigby" and songs by Dylan and Donovan, to Ezra Pound when visiting him in Venice in 1967. The visit was a gesture by Ginsberg to assure Pound that, despite the latter's embrace of fascism and antisemitism during World War II, his standing as the originator of twentieth-century poetry remained acknowledged in the 1960s.[130]

- ^ In author George Case's view, the track "encapsulated the childlike, communal surrealism of an LSD trip" on an album full of drug-inspired music and lyrics.[136]

- ^ In a partly ad-libbed scene in that 1964 film, Lennon takes a bubble bath and plays with a toy submarine, channelling Adolf Hitler in his imitation of a U-boat captain.[138]

- ^ According to Brodax, the plot was subsequently inspired by Lennon phoning him at 3 am and suggesting, "Wouldn't it be great if Ringo was followed down the street by a yellow submarine?"[142]

- ^ In 1968, McCartney produced a brass band instrumental version of "Yellow Submarine" by the Black Dyke Mills Band.[146] It was issued as the B-side of "Thingumybob",[147] one of the "First Four" singles on the Beatles' Apple record label.[148]

- ^ Harrison's son Dhani has said it was only through the song that he realised his father had once been a Beatle. Dhani recalled being chased home from school by children singing "Yellow Submarine" and wondering why. He added: "I freaked out on my dad: 'Why didn't you tell me you were in the Beatles?' And he said, 'Oh, sorry. Probably should have told you that.'"[157]

- ^ In late 1968, American cult leader Charles Manson named his headquarters at Canoga Park in California "Yellow Submarine" after the song.[162]

References

[edit]- ^ Plagenhoef, Scott (9 September 2009). "The Beatles: Revolver Album Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ Easlea, Daryl (2007). "The Beatles Revolver Review". BBC Music. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Case 2010, p. 230: "the jaunty psychedelia of 'Yellow Submarine'".

- ^ Sante, Luc (25 March 2018). "The Kinks: Something Else". Pitchfork. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

Most significant beat combos had their stab at [music hall] at some point, including...the Beatles ("Yellow Submarine,"...

- ^ a b Turner 2016, p. 185.

- ^ a b Winn 2009, p. 93.

- ^ a b "Lennon & McCartney Interview: Ivor Novello Awards, 3/20/1967". Beatles Interviews Database. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ^ a b "Yellow Submarine". Beatles Interview Database. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ a b Everett 1999, p. 56.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, p. 65.

- ^ John Lennon Interview 1972 Hit Parader Magazine.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 286–87.

- ^ a b Sheffield, Rob (7 September 2022). "The Beatles' Unheard 'Revolver': An Exclusive Preview of a Blockbuster Archival Release". rollingstone.com. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ Turner 2016, pp. 187–88.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 287.

- ^ Turner 2016, p. 186.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, pp. 51–53.

- ^ Kurlansky 2005, p. 188.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Norman 2008, p. 424.

- ^ Kruth 2015, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Reising & LeBlanc 2009, p. 103.

- ^ Stark 2005, p. 188.

- ^ The Beatles 2000, p. 208.

- ^ Gould 2007, p. 355.

- ^ a b c d e Pollack, Alan W. (24 December 1994). "Notes on 'Yellow Submarine'". Soundscapes. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ Reising & LeBlanc 2009, p. 101.

- ^ a b Reising & LeBlanc 2009, pp. 102–04.

- ^ a b Echard 2017, p. 95.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, p. 138.

- ^ Unterberger 2006, p. 141.

- ^ Philo 2015, p. 107.

- ^ Frontani 2007, pp. 119, 121–22.

- ^ a b c Winn 2009, p. 22.

- ^ a b c d e MacDonald 2005, p. 206.

- ^ Philo 2015, p. 105.

- ^ a b c Lewisohn 2005, p. 80.

- ^ a b c Everett 1999, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Reising & LeBlanc 2009, p. 96.

- ^ Perone 2012, p. 86.

- ^ a b c d Everett 1999, p. 327.

- ^ a b Riley 2002, p. 188.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Everett 1999, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lewisohn 2005, p. 81.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rodriguez 2012, p. 140.

- ^ a b Rolling Stone staff (19 September 2011). "100 Greatest Beatles Songs: 74. 'Yellow Submarine'". rollingstone.com. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ Turner 2016, p. 188.

- ^ a b c Spitz 2005, p. 612.

- ^ a b c d e f Gould 2007, p. 356.

- ^ a b Womack 2014, p. 1027.

- ^ a b c Rodriguez 2012, p. 142.

- ^ a b Winn 2009, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Womack 2014, p. 1026.

- ^ The Beatles 2000, p. 27.

- ^ Echard 2017, pp. 94–95.

- ^ a b Rodriguez 2012, pp. 140–41.

- ^ a b Smith, Alan (19 August 1966). "George Martin: Make Them Top Here!". NME. Available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ a b Rodriguez 2012, pp. 141–42.

- ^ Clayson 2003, p. 159.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, pp. 81, 82.

- ^ Everett 1999, pp. 57, 327.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, pp. 379–80, 491.

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 23.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, p. 167.

- ^ a b Petridis, Alex (26 September 2019). "The Beatles' Singles – Ranked!". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, pp. 85, 200.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik 1976, pp. 55, 56.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 629.

- ^ Miles 2001, pp. 237, 240.

- ^ a b c Schaffner 1978, p. 62.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "The Beatles 'Eleanor Rigby'". AllMusic. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ Unterberger 2006, p. 318.

- ^ Everett 1999, pp. 68, 328.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, p. 168.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, p. 85.

- ^ a b c "Yellow Submarine/Eleanor Rigby". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 338.

- ^ Womack 2014, p. 1025.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 175.

- ^ Myers, Justin (9 January 2016). "The Biggest Song of Every Year Revealed" > "Image Gallery" > "Slide 51/65". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ Everett 1999, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Leonard 2014, pp. 114–15.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 627.

- ^ Doggett 2007, p. 83.

- ^ Norman 2008, p. 450.

- ^ Savage 2015, p. 324.

- ^ Frontani 2007, pp. 101–01.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 240.

- ^ Philo 2015, pp. 108–09.

- ^ a b Philo 2015, p. 110.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, p. 169.

- ^ a b "Cash Box Top 100 – Week of September 10, 1966". Cash Box. 10 September 1966. p. 4.

- ^ "Record World 100 Top Pops – Week of September 10, 1966". Record World. 10 September 1966. p. 15.

- ^ Gould 2007, pp. 356–57.

- ^ Turner 2016, pp. 292–93.

- ^ Turner 2016, p. 293.

- ^ a b Rodriguez 2012, p. 172.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 331.

- ^ Turner 2016, pp. 259–60.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 630.

- ^ Sutherland, Steve, ed. (2003). NME Originals: Lennon. London: IPC Ignite!. p. 40.

- ^ Mulvey, John, ed. (2015). "July–September: LPs/Singles". The History of Rock: 1966. London: Time Inc. p. 78. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "Singles Reviews: Pop Spotlights". Billboard. 13 August 1966. p. 18. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ "Record Reviews". Cash Box. 13 August 1966. p. 24.

- ^ "Single Picks of the Week" (PDF). Record World. 13 August 1966. p. 1. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ Green, Richard; Jones, Peter (30 July 1966). "The Beatles: Revolver (Parlophone)". Record Mirror. Available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Goldstein, Richard (25 August 1966). "Pop Eye: On 'Revolver'". The Village Voice. pp. 25–26. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ Cleave, Maureen (30 July 1966). "The Beatles: Revolver (Parlophone PMC 7009)". The Evening Standard. Available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Turner 2016, pp. 260–61.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, p. 176.

- ^ Staff writer (30 July 1966). "Ray Davies Reviews the Beatles LP". Disc and Music Echo. p. 16.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, p. 175.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 69.

- ^ Carr & Tyler 1978, p. 58.

- ^ Frontani 2007, p. 122.

- ^ Unterberger 2006, p. 152.

- ^ Savage 2015, p. 545.

- ^ Riley 2002, pp. 187–88.

- ^ Ward, Thomas. "The Beatles 'Yellow Submarine'". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d Doggett 2007, p. 82.

- ^ Doggett 2007, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Frontani 2007, pp. 123–24.

- ^ a b Stark 2005, pp. 188–89.

- ^ Doggett 2007, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Turner 2016, p. 295.

- ^ Turner 2016, pp. 356–58.

- ^ Leonard 2014, pp. 127–28.

- ^ Reising & LeBlanc 2009, pp. 106–07.

- ^ Stark 2005, p. 189.

- ^ Kurlansky 2005, p. 133.

- ^ Perone 2012, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Kurlansky 2005, pp. 183, 188.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, pp. 65–66.

- ^ a b Glynn 2013, p. 136.

- ^ Gould 2007, p. 357.

- ^ Case 2010, p. 28.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (December 1967). "Columns: December 1967". Esquire. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ Norman 2008, pp. 355–56.

- ^ Glynn 2013, pp. 131–32.

- ^ Sounes 2010, p. 178.

- ^ Glynn 2013, p. 132.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, p. 99.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 239.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 330.

- ^ Womack 2014, p. 1030.

- ^ The Beatles 2000, p. 289.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 68.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, pp. 110–11.

- ^ Frontani 2007, p. 176.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, pp. 100–01.

- ^ a b "Yellow Submarine Moves to Airport". BBC News. 9 July 2005. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Womack 2014, p. 1028.

- ^ Badman 2001, pp. 630, 631–32.

- ^ Chapman 2015, p. 509.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, pp. 60, 62.

- ^ Shaar Murray, Charles (2002). "Revolver: Talking About a Revolution". Mojo Special Limited Edition: 1000 Days That Shook the World (The Psychedelic Beatles – April 1, 1965 to December 26, 1967). London: Emap. p. 75.

- ^ Whitehead, John W. (14 October 2011). "The Quiet One". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ Campbell, Rachel (21 January 2005). "Feeling Blue About the Inauguration". The Journal Times. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ O'Brien, Carl (7 July 2005). "Three Irish Mammies in Vanguard of Demonstration". The Irish Times. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Booth, Robert (29 April 2011). "Royal Wedding: Police Criticised for Pre-emptive Strikes Against Protesters". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Marsh, Philip (15 May 2015). "No One Would Riot for Less: The UK General Election, "Shy Tories" and the Eating of Lord Ashdown's Hat". The Weeklings. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Doggett 2007, p. 305.

- ^ Clayson 2003, pp. 195–96.

- ^ Kruth 2015, p. 154.

- ^ Case 2010, p. 230.

- ^ Sounes 2010, pp. 143–44, 397.

- ^ Sounes 2010, p. 179.

- ^ Badman 2001, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Womack 2014, p. 612.

- ^ Sounes 2010, p. 397.

- ^ Badman 2001, pp. 306, 376.

- ^ Rowe, Matt (18 September 2015). "The Beatles 1 to Be Reissued with New Audio Remixes ... and Videos". The Morton Report. Archived from the original on 29 December 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ "Yellow Submarine Anniversary 7" Picture Disc". thebeatles.com. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ "Why are Villarreal called the Yellow Submarine?". Talksport. 28 April 2016.

- ^ "Go-Set Australian Charts – 5 October 1966". poparchives.com.au. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ "The Beatles – Yellow Submarine". austriancharts.at. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "The Beatles – Yellow Submarine". ultratop.be. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "RPM 100 (September 19, 1966)". Library and Archives Canada. 17 July 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "The Beatles - Salgshitlisterne Top 20". Danske Hitlister. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ Nyman, Jake (2005). Suomi soi 4: Suuri suomalainen listakirja (in Finnish) (1st ed.). Helsinki: Tammi. ISBN 951-31-2503-3.

- ^ "Search by Song Title > Yellow Submarine". irishcharts.ie. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "Classifiche". Musica e dischi (in Italian). Retrieved 31 May 2022. Set "Tipo" on "Singoli". Then, in the "Titolo" field, search "Yellow submarine".

- ^ "Nederlandse Top 40 – The Beatles" (in Dutch). Dutch Top 40.

- ^ "The Beatles – Yellow Submarine / Eleanor Rigby" (in Dutch). Single Top 100.

- ^ "23-Sep-66: The NZ Hit Parade". Flavour of New Zealand. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ "The Beatles – Yellow Submarine (song)". norwegiancharts.com. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ Kimberley, C (2000). Zimbabwe: Singles Chart Book. p. 10.

- ^ Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959-2002 (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

- ^ "Swedish Charts 1966–1969/Kvällstoppen – Listresultaten vecka för vecka > Augusti 1966" (PDF) (in Swedish). hitsallertijden.nl. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ Hallberg, Eric; Henningsson, Ulf (1998). Eric Hallberg, Ulf Henningsson presenterar Tio i topp med de utslagna på försök: 1961 - 74. Premium Publishing. p. 53. ISBN 919727125X.

- ^ "The Beatles Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ a b "The Beatles – Yellow Submarine". Offizielle Deutsche Charts. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ "50 Back Catalogue Singles – 27 November 2010". Ultratop 50. Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ "Sixties City - Pop Music Charts - Every Week Of The Sixties". Sixtiescity.net. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "Top 100 Hits of 1966/Top 100 Songs of 1966". Musicoutfitters.com. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "Cash Box Year-End Charts: Top 100 Pop Singles, December 24, 1966". Archived from the original on 23 November 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "From the Music Capitals of the world - Oslo". Billboard. 18 March 1967. p. 58. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ "British single certifications – Beatles – Yellow Submarine". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ "American single certifications – The Beatles – Yellow Submarine". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Badman, Keith (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After the Break-Up 1970–2001. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-8307-6.

- The Beatles (2000). The Beatles Anthology. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-8118-2684-8.

- Carr, Roy; Tyler, Tony (1978). The Beatles: An Illustrated Record. London: Trewin Copplestone Publishing. ISBN 0-450-04170-0.

- Case, George (2010). Out of Our Heads: Rock 'n' Roll Before the Drugs Wore Off. Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-967-1.

- Castleman, Harry; Podrazik, Walter J. (1976). All Together Now: The First Complete Beatles Discography 1961–1975. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-25680-8.

- Chapman, Rob (2015). Psychedelia and Other Colours. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-28200-5.

- Clayson, Alan (2003). Ringo Starr. London: Sanctuary. ISBN 1-86074-488-5.

- Doggett, Peter (2007). There's a Riot Going On: Revolutionaries, Rock Stars, and the Rise and Fall of '60s Counter-Culture. Edinburgh, UK: Canongate Books. ISBN 978-1-84195-940-5.

- Echard, William (2017). Psychedelic Popular Music: A History Through Musical Topic Theory. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-02659-0.

- Everett, Walter (1999). The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver Through the Anthology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512941-0.

- Frontani, Michael R. (2007). The Beatles: Image and the Media. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-966-8.

- Glynn, Stephen (2013). The British Pop Music Film: The Beatles and Beyond. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-39222-9.

- Gould, Jonathan (2007). Can't Buy Me Love: The Beatles, Britain and America. London: Piatkus. ISBN 978-0-7499-2988-6.

- Kruth, John (2015). This Bird Has Flown: The Enduring Beauty of Rubber Soul, Fifty Years On. Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-61713-573-6.

- Kurlansky, Mark (2005). 1968: The Year That Rocked the World. New York, NY: Random House. ISBN 978-0-345455826.

- Leonard, Candy (2014). Beatleness: How the Beatles and Their Fans Remade the World. New York, NY: Arcade Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62872-417-2.

- Lewisohn, Mark (2005) [1988]. The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions: The Official Story of the Abbey Road Years 1962–1970. London: Bounty Books. ISBN 978-0-7537-2545-0.

- MacDonald, Ian (2005). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties (2nd rev. ed.). London: Pimlico. ISBN 1-84413-828-3.

- Miles, Barry (1997). Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now. New York, NY: Henry Holt & Company. ISBN 0-8050-5249-6.

- Miles, Barry (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-8308-9.

- Norman, Philip (2008). John Lennon: The Life. New York, NY: Ecco. ISBN 978-0-06-075402-0.

- Perone, James E. (2012). The Album: A Guide to Pop Music's Most Provocative, Influential and Important Creations. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-313-37906-2.

- Philo, Simon (2015). British Invasion: The Crosscurrents of Musical Influence. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-8626-1.

- Reising, Russell; LeBlanc, Jim (2009). "Magical Mystery Tours, and Other Trips: Yellow submarines, newspaper taxis, and the Beatles' psychedelic years". In Womack, Kenneth (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Beatles. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68976-2.

- Riley, Tim (2002) [1988]. Tell Me Why – The Beatles: Album by Album, Song by Song, the Sixties and After. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81120-3.

- Rodriguez, Robert (2012). Revolver: How the Beatles Reimagined Rock 'n' Roll. Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-61713-009-0.

- Savage, Jon (2015). 1966: The Year the Decade Exploded. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-27763-6.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1978). The Beatles Forever. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-055087-5.

- Sounes, Howard (2010). Fab: An Intimate Life of Paul McCartney. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-723705-0.

- Spitz, Bob (2005). The Beatles: The Biography. Boston, MA: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-80352-9.

- Stark, Steven D. (2005). Meet the Beatles: A Cultural History of the Band That Shook Youth, Gender, and the World. New York, NY: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-000893-2.

- Turner, Steve (2016). Beatles '66: The Revolutionary Year. New York, NY: Ecco. ISBN 978-0-06-247558-9.

- Unterberger, Richie (2006). The Unreleased Beatles: Music & Film. San Francisco, CA: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-892-6.

- Winn, John C. (2009). That Magic Feeling: The Beatles' Recorded Legacy, Volume Two, 1966–1970. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-45239-9.

- Womack, Kenneth (2014). The Beatles Encyclopedia: Everything Fab Four. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-39171-2.

External links

[edit]- The Beatles' Yellow Submarine

- 1966 songs

- 1966 singles

- The Beatles songs

- Parlophone singles

- Capitol Records singles

- Songs written by Lennon–McCartney

- Song recordings produced by George Martin

- Songs published by Northern Songs

- Cashbox number-one singles

- RPM Top Singles number-one singles

- Number-one singles in Germany

- Irish Singles Chart number-one singles

- Number-one singles in New Zealand

- Number-one singles in Norway

- UK singles chart number-one singles

- Ringo Starr songs

- English children's songs

- Novelty songs

- Songs about boats

- Songs about oceans and seas

- Fictional submarines