Anschluss

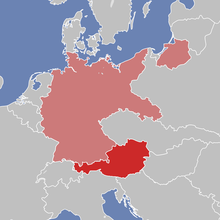

| Territorial evolution of Germany in the 20th century |

|---|

| Events leading to World War II |

|---|

The Anschluss (German: [ˈʔanʃlʊs] , or Anschluß before the German orthography reform of 1996,[1] "joining"), also known as the Anschluss Österreichs (, English: Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany on 12 March 1938.

The idea of an Anschluss (a united Austria and Germany that would form a "Greater Germany")[a] began after the unification of Germany excluded Austria and the German Austrians from the Prussian-dominated German Empire in 1871. Following the end of World War I with the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in 1918, the newly formed Republic of German-Austria attempted to form a union with Germany, but the Treaty of Saint Germain (10 September 1919) and the Treaty of Versailles (28 June 1919) forbade both the union and the continued use of the name "German-Austria" (Deutschösterreich); and stripped Austria of some of its territories, such as the Sudetenland.

Prior to the Anschluss, there had been strong support from people of all backgrounds in both Austria and Germany for unification of the two countries.[3] In the immediate aftermath of the dissolution of the Habsburg Monarchy—with Austria left as a broken remnant, deprived of most of the territories it ruled for centuries and undergoing a severe economic crisis—the idea of unity with Germany seemed attractive also to many citizens of the political Left and Center. Had the WWI victors allowed it, Austria would have united with Germany as a freely taken democratic decision. But after 1933 desire for unification could be identified with the Nazis, for whom it was an integral part of the Nazi "Heim ins Reich" concept, which sought to incorporate as many Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans outside Germany) as possible into a "Greater Germany".[4]

In the early 1930s, there was still significant resistance in Austria—even among some Austrian Nazis—to suggestions that Austria should be annexed to Germany and the Austrian state dissolved completely. Consequently, after the German Nazis, under the Austrian-born Adolf Hitler, took control of Germany (1933), their agents cultivated pro-unification tendencies in Austria, and sought to undermine the Austrian government, which was controlled by the Austrofascist Fatherland Front. During an attempted coup in 1934, Austrian chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss was assassinated by Austrian Nazis. The defeat of the coup prompted many leading Austrian Nazis to go into exile in Germany, where they continued their efforts for unification of the two countries.

In early 1938, under increasing pressure from pro-unification activists, Austrian chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg announced that there would be a referendum on a possible union with Germany to be held on 13 March. Portraying this as defying the popular will in Austria and Germany, Hitler threatened an invasion and secretly pressured Schuschnigg to resign. The referendum was canceled. On 12 March, the German Wehrmacht crossed the border into Austria, unopposed by the Austrian military; the Germans were greeted with great enthusiasm. A plebiscite held on 10 April officially ratified Austria's annexation by the Reich.

Historical background

Prior to 1918

The idea of grouping all Germans into one nation-state had been the subject of debate in the 19th century from the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 until the break-up of the German Confederation in 1866. Austria had wanted a Großdeutsche Lösung (greater Germany solution), whereby the German states would unite under the leadership of German Austrians (Habsburgs). This solution would have included all the German states (including the non-German regions of Austria), but Prussia would have had to accept a secondary role. This controversy, called dualism, dominated Prusso-Austrian diplomacy and the politics of the German states in the mid-nineteenth century.[5]

In 1866 the feud finally came to an end during the German war in which the Prussians defeated the Austrians and thereby excluded Austria and German Austrians from Germany. The Prussian statesman Otto von Bismarck formed the North German Confederation, which included most of the remaining German states, aside from a few in the southwestern region of the German-inhabited lands, and further expanded the power of Prussia. Bismarck used the Franco-Prussian war (1870-1871) as a way to convince southwestern German states, including the Kingdom of Bavaria, to side with Prussia against the Second French Empire. Due to Prussia's quick victory, the debate was settled and in 1871 the "Kleindeutsch" German Empire based on the leadership of Bismarck and the Kingdom of Prussia formed – this excluded Austria.[6] Besides ensuring Prussian domination of a united Germany, the exclusion of Austria also ensured that Germany would have a substantial Protestant majority.

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, the Ausgleich, provided for a dual sovereignty, the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary, under Franz Joseph I. The Austrian-Hungarian rule of this diverse empire included various different ethnic groups including Hungarians, Slavic ethnic groups such as Croats, Czechs, Poles, Rusyns, Serbs, Slovaks, Slovenes, and Ukrainians, as well as Italians and Romanians ruled by a German minority.[7] The empire caused tensions between the various ethnic groups. Many Austrian pan-Germans showed loyalty to Bismarck[8] and only to Germany, wore symbols that were temporarily banned in Austrian schools and advocated the dissolution of the empire to allow Austria to rejoin Germany, as it had been during the German Confederation of 1815-1866.[9][10] Although many Austrians supported pan-Germanism, many others still showed allegiance to the Habsburg Monarchy and wished for Austria to remain an independent country.[11]

Austria during the First Austrian Republic: 1918–1934

By the end of World War I in 1918, Austria had not officially participated in internal German affairs for more than fifty years - since the Peace of Prague that concluded the Austro-Prussian War of 1866.

Elite and popular opinion in rump Austria after 1918 largely favored some sort of union with Germany, but the 1919 peace treaties explicitly forbade this.[12] The Austro-Hungarian Empire had collapsed in 1918, and on 12 November that year German Austria was declared a republic. An Austrian provisional national assembly drafted a provisional constitution that stated that "German Austria is a democratic republic" (Article 1) and "German Austria is a component of the German Republic" (Article 2). Later plebiscites in the German border provinces of Tyrol and Salzburg yielded majorities of 98% and 99% in favor of a unification with the German (i.e. Weimar) Republic.

In the aftermath of a prohibition of an Anschluss, Germans in both Austria and Germany pointed to a contradiction in the national self-determination principle because the treaties failed to grant self-determination to the ethnic Germans (such as German Austrians and Sudeten Germans) outside of the German Reich.[13][14]

The Treaty of Versailles and the Treaty of Saint-Germain (both signed in 1919) explicitly prohibited the political inclusion of Austria in the German state. Hugo Preuss, the drafter of the German Weimar Constitution, criticized this measure; he saw the prohibition as a contradiction of the Wilsonian principle of self-determination of peoples,[15] intended to help bring peace to Europe.[16] Following the destruction of World War I, however, France and Britain feared the power of a larger Germany and had begun to disempower the current one. Austrian particularism, especially among the nobility, also played a role in the decisions;[citation needed] Austria was Roman Catholic, while Germany's government was dominated by Protestants (for example, the Prussian nobility was Lutheran). The constitutions of the Weimar Republic and the First Austrian Republic both included the political goal of unification, which democratic parties[which?] widely supported. In the early 1930s, popular support for union with Germany remained overwhelming in Austria, and the Austrian government looked to a possible customs union with the German Republic in 1931.

Nazi Germany and Austria

When the Nazis, led by Adolf Hitler, rose to power in the Weimar Republic, the Austrian government withdrew from economic ties. Like Germany, Austria experienced the economic turbulence which was a result of the Great Depression, with a high unemployment rate, and unstable commerce and industry. During the 1920s it was a target for German investment capital. By 1937, rapid German rearmament increased Berlin's interest in annexing Austria, rich in raw materials and labour. It supplied Germany with magnesium and the products of the iron, textile and machine industries. It had gold and foreign currency reserves, many unemployed skilled workers, hundreds of idle factories, and large potential hydroelectric resources.[17]

Hitler, an Austrian German by birth,[18][b] picked up his German nationalist ideas at a young age. Whilst infiltrating the German Workers' Party (DAP), Hitler became involved in a heated political argument with a visitor, a Professor Baumann, who proposed that Bavaria should break away from Prussia and found a new South German nation with Austria. In vehemently attacking the man's arguments he made an impression on the other party members with his oratory skills and, according to Hitler, the "professor" left the hall acknowledging unequivocal defeat.[20] Impressed with Hitler, Anton Drexler invited him to join the DAP. Hitler accepted on 12 September 1919,[21] becoming the party's 55th member.[22] After becoming leader of the DAP, Hitler addressed a crowd on 24 February 1920, and in an effort to appeal to wider parts of the German population, the DAP was renamed the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP).[23]

As its first point, the 1920 National Socialist Program stated, "We demand the unification of all Germans in the Greater Germany on the basis of the people's right to self-determination." Hitler argued in a 1921 essay that the German Reich had a single task of, "incorporating the ten million German-Austrians in the Empire and dethroning the Habsburgs, the most miserable dynasty ever ruling."[24] The Nazis aimed to re-unite all Germans who were either born in the Reich or living outside it in order to create an "all-German Reich". Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf (1925) that he would create a union between his birth country Austria and Germany by any means possible.[25][non-primary source needed]

The First Austrian Republic, which was dominated from the late 1920s by the anti-Anschluss[26] Catholic nationalist Christian Social Party (CS), gradually disintegrated from 1933 (dissolution of parliament and ban on the Austrian National Socialists) to 1934 (Austrian Civil War in February and ban on all remaining parties except the CS). The government evolved into a corporatist, one-party government that combined the CS and the paramilitary Heimwehr. It controlled labor relations and the press. (See Austrofascism and Patriotic Front).[citation needed]

Power was centralized in the office of the chancellor, who was empowered to rule by decree. The dominance of the Christian Social Party (whose economic policies were based on the papal encyclical Rerum novarum) was an Austrian phenomenon. Austria's national identity had strong Catholic elements that were incorporated into the movement, by way of clerical authoritarian tendencies which were not found in Nazism.[example needed] Engelbert Dollfuss and his successor, Kurt Schuschnigg, turned to Benito Mussolini's Italy for inspiration and support. The statist corporatism which is often referred to as Austrofascism and described as a form of clerical fascism, bore a stronger resemblance to Italian Fascism rather than German National Socialism.[citation needed]

Mussolini supported the independence of Austria, largely due to his concern that Hitler would eventually press for the return of Italian territories which had once been ruled by Austria. However, Mussolini needed German support in Ethiopia (see Second Italo-Abyssinian War). After receiving Hitler's personal assurance that Germany would not seek territorial concessions from Italy, Mussolini entered into a client relationship with Berlin that began with the formation of the Berlin–Rome Axis in 1937.[citation needed]

Austrian Civil War to Anschluss

The Austrian Nazi Party failed to win any seats in the November 1930 general election, but its popularity grew in Austria after Hitler came to power in Germany. The idea of the country joining Germany also grew in popularity, thanks in part to a Nazi propaganda campaign which used slogans such as Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer ("One People, One Empire, One Leader") to try to convince Austrians to advocate for an Anschluss to the German Reich.[27] Anschluss might have occurred by democratic process had Austrian Nazis not begun a terrorism campaign. According to John Gunther in 1936, "In 1932 Austria was probably eighty percent pro-Anschluss".[28]

When Germany permitted residents of Austria to vote[clarification needed] on 5 March 1933, three special trains, boats and trucks brought such masses to Passau that the SS staged a ceremonial welcome.[29] Gunther wrote that by the end of 1933 Austrian public opinion about German annexation was at least 60% against.[28] On 25 July 1934, Dollfuss was assassinated by Austrian Nazis in a failed coup. Afterwards, leading Austrian Nazis fled to Germany but they continued to push for unification from there. The remaining Austrian Nazis continued terrorist attacks against Austrian governmental institutions, causing a death toll of more than 800 between 1934 and 1938.

Dollfuss's successor was Kurt Schuschnigg, who followed a political course similar to his predecessor. In 1935 Schuschnigg used the police to suppress Nazi supporters. Police actions under Schuschnigg included gathering Nazis (and Social Democrats) and holding them in internment camps. The Austrofascism of Austria between 1934–1938 focused on the history of Austria and opposed the absorption of Austria into Nazi Germany (according to the philosophy Austrians were "superior Germans"). Schuschnigg called Austria the "better German state" but struggled to keep Austria independent.

In an attempt to put Schuschnigg's mind at rest, Hitler delivered a speech at the Reichstag and said, "Germany neither intends nor wishes to interfere in the internal affairs of Austria, to annex Austria or to conclude an Anschluss."[30]

By 1936 the damage to Austria from the German boycott was too great.[clarification needed] That summer Schuschnigg told Mussolini that his country had to come to an agreement with Germany. On 11 July 1936 he signed an agreement with German ambassador Franz von Papen, in which Schuschnigg agreed to the release of Nazis imprisoned in Austria and Germany promised to respect Austrian sovereignty.[28] Under the terms of the Austro-German treaty, Austria declared itself a "German state" that would always follow Germany's lead in foreign policy, and members of the "National Opposition" were allowed to enter the cabinet, in exchange for which the Austrian Nazis promised to cease their terrorist attacks against the government. This did not satisfy Hitler and the pro-German Austrian Nazis grew in strength.

In September 1936, Hitler launched the Four-Year Plan that called for a dramatic increase in military spending and to make Germany as autarkic as possible with the aim of having the Reich ready to fight a world war by 1940.[31] The Four Year Plan required huge investments in the Reichswerke steel works, a programme for developing synthetic oil that soon went wildly over budget, and programmes for producing more chemicals and aluminium; the plan called for a policy of substituting imports and rationalizing industry to achieve its goals that failed completely.[31] As the Four Year Plan fell further and further behind its targets, Hermann Göring, the chief of the Four Year Plan office, began to press for an Anschluss as a way of securing Austria's iron and other raw materials as a solution to the problems with the Four Year Plan.[32] The British historian Sir Ian Kershaw wrote:

...above all, it was Hermann Göring, at this time close to the pinnacle of his power, who far more than Hitler, throughout 1937 made the running and pushed the hardest for an early and radical solution to the 'Austrian Question'. Göring was not simply operating as Hitler's agent in matters relating to the 'Austrian Question'. His approach differed in emphasis in significant respects...But Göring's broad notions of foreign policy, which he pushed to a great extent on his own initiative in the mid-1930s drew more on traditional pan-German concepts of nationalist power-politics to attain hegemony in Europe than on the racial dogmatism central to Hitler's ideology.[32]

Göring was far more interested in the return of the former German colonies in Africa than was Hitler, believed up to 1939 in the possibility of an Anglo-German alliance (an idea that Hitler had abandoned by late 1937), and wanted all Eastern Europe in the German economic sphere of influence.[33] Göring did not share Hitler's interest in Lebensraum ("living space") as for him, merely having Eastern Europe in the German economic sphere of influence was sufficient.[32] In this context, having Austria annexed to Germany was the key towards bringing Eastern Europe into Göring's desired Grossraumwirtschaft ("greater economic space").[33]

Faced with problems in the Four Year Plan, Göring had become the loudest voice in Germany, calling for an Anschluss, even at the risk of losing an alliance with Italy.[34] In April 1937, in a secret speech before a group of German industrialists, Göring stated that the only solution to the problems with meeting the steel production targets laid out by the Four Year Plan was to annex Austria, which Göring noted was rich in iron.[34] Göring did not give a date for the Anschluss, but given that Four Year Plan's targets all had to be met by September 1940, and the current problems with meeting the steel production targets, suggested that he wanted an Anschluss in the very near-future.[34]

End of an independent Austria

Hitler told Goebbels in the late summer of 1937 that eventually Austria would have to be taken "by force".[35] On 5 November 1937, Hitler called a meeting with the Foreign Minister Konstantin von Neurath, the War Minister Field Marshal Werner von Blomberg, the Army commander General Werner von Fritsch, the Kriegsmarine commander Admiral Erich Raeder and the Luftwaffe commander Hermann Göring recorded in the Hossbach Memorandum. At the conference, Hitler stated that economic problems were causing Germany to fall behind in the arms race with Britain and France, and that the only solution was to launch in the near-future a series of wars to seize Austria and Czechoslovakia, whose economies would be plundered to give Germany the lead in the arms race.[36][37] In early 1938, Hitler was seriously considering replacing Papen as ambassador to Austria with either Colonel Hermann Kriebel, the German consul in Shanghai or Albert Forster, the Gauleiter of Danzig.[38] Significantly, neither Kriebel nor Forster were professional diplomats with Kriebel being one of the leaders of the 1923 Munich Beerhall putsch who had been appointed consul in Shanghai to facilitate his work as an arms dealer in China while Forster was a Gauleiter who had proven he could get along with the Poles in his position in the Free City of Danzig; both men were Nazis who had shown some diplomatic skill.[38] On 25 January 1938, the Austrian police raided the Vienna headquarters of the Austrian Nazi Party, arresting Gauleiter Leopold Tavs, the deputy to Captain Josef Leopold, discovered a cache of arms and plans for a putsch.[38]

Following increasing violence and demands from Hitler that Austria agree to a union, Schuschnigg met Hitler at Berchtesgaden on 12 February 1938, in an attempt to avoid the takeover of Austria. Hitler presented Schuschnigg with a set of demands that included appointing Nazi sympathizers to positions of power in the government. The key appointment was that of Arthur Seyss-Inquart as Minister of Public Security, with full, unlimited control of the police. In return Hitler would publicly reaffirm the treaty of 11 July 1936 and reaffirm his support for Austria's national sovereignty. Browbeaten and threatened by Hitler, Schuschnigg agreed to these demands and put them into effect.[39]

Seyss-Inquart was a long-time supporter of the Nazis who sought the union of all Germans in one state. Leopold argues he was a moderate who favoured an evolutionary approach to union. He opposed the violent tactics of the Austrian Nazis, cooperated with Catholic groups, and wanted to preserve a measure of Austrian identity within Nazi Germany.[40]

On 20 February, Hitler made a speech before the Reichstag which was broadcast live and which for the first time was relayed also by the Austrian radio network. A key phrase in the speech which was aimed at the Germans living in Austria and Czechoslovakia was: "The German Reich is no longer willing to tolerate the suppression of ten million Germans across its borders."[41]

Schuschnigg announces a referendum

On 9 March 1938, in the face of rioting by the small, but virulent, Austrian Nazi Party and ever-expanding German demands on Austria, Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg called a referendum (plebiscite) on the issue, to be held on 13 March. Infuriated, on 11 March, Adolf Hitler threatened invasion of Austria, and demanded Chancellor von Schuschnigg's resignation and the appointment of the Nazi Arthur Seyss-Inquart as his replacement. Hitler's plan was for Seyss-Inquart to call immediately for German troops to rush to Austria's aid, restoring order and giving the invasion an air of legitimacy. In the face of this threat, Schuschnigg informed Seyss-Inquart that the plebiscite would be cancelled.

To secure a large majority in the referendum, Schuschnigg dismantled the one-party state. He agreed to legalize the Social Democrats and their trade unions in return for their support in the referendum.[4] He also set the minimum voting age at 24 to exclude younger voters because the Nazi movement was most popular among the young.[42] In contrast, Hitler had lowered the voting age for German elections held under Nazi rule, largely to compensate for the removal of Jews and other ethnic minorities from the German electorate following enactment of the Nuremberg Laws in 1935.[citation needed]

The plan went awry when it became apparent that Hitler would not stand by while Austria declared its independence by public vote. Hitler declared that the referendum would be subject to major fraud and that Germany would never accept it. In addition, the German ministry of propaganda issued press reports that riots had broken out in Austria and that large parts of the Austrian population were calling for German troops to restore order. Schuschnigg immediately responded that reports of riots were false.[43]

Hitler sent an ultimatum to Schuschnigg on 11 March, demanding that he hand over all power to the Austrian Nazis or face an invasion. The ultimatum was set to expire at noon, but was extended by two hours. Without waiting for an answer, Hitler had already signed the order to send troops into Austria at one o'clock.[44] Nevertheless, the German Führer underestimated his opposition.

As Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Edgar Ansel Mowrer, reporting from Paris for CBS, observed: "There is no one in all France who does not believe that Hitler invaded Austria not to hold a genuine plebiscite, but to prevent the plebiscite planned by Schuschnigg from demonstrating to the entire world just how little hold National Socialism really had on that tiny country."[45]

Schuschnigg desperately sought support for Austrian independence in the hours following the ultimatum. Realizing that neither France nor Britain was willing to offer assistance, Schuschnigg resigned on the evening of 11 March, but President Wilhelm Miklas refused to appoint Seyss-Inquart as Chancellor. At 8:45 pm, Hitler, tired of waiting, ordered the invasion to commence at dawn on 12 March regardless.[46] Around 10 pm, a forged telegram was sent in Seyss-Inquart's name asking for German troops, since he was not yet Chancellor and was unable to do so himself. Seyss-Inquart was not installed as Chancellor until after midnight, when Miklas resigned himself to the inevitable.[44][4] In the radio broadcast in which he announced his resignation, he argued that he accepted the changes and allowed the Nazis to take over the government 'to avoid the shedding of fraternal blood [Bruderblut]'.[47] Seyss-Inquart was appointed chancellor after midnight on 12 March.

It is said that after listening to Bruckner's Seventh Symphony, Hitler cried: "How can anyone say that Austria is not German! Is there anything more German than our old pure Austrianness?"[48]

German troops march into Austria

On the morning of 12 March 1938, the 8th Army of the German Wehrmacht crossed the border into Austria. The troops were greeted by cheering Austrians with Nazi salutes, Nazi flags, and flowers.[49] For the Wehrmacht, the invasion was the first big test of its machinery. Although the invading forces were badly organized and coordination among the units was poor, it mattered little because the Austrian government had ordered the Austrian Bundesheer not to resist.[50]

That afternoon, Hitler, riding in a car, crossed the border at his birthplace, Braunau am Inn, with a 4,000 man bodyguard.[45] In the evening, he arrived at Linz and was given an enthusiastic welcome. The enthusiasm displayed toward Hitler and the Germans surprised both Nazis and non-Nazis, as most people had believed that a majority of Austrians opposed Anschluss.[51][52] Many Germans from both Austria and Germany welcomed the Anschluss as they saw it as completing the complex and long overdue German unification of all Germans united into one state.[53] Hitler had originally intended to leave Austria as a satellite state with Seyss-Inquart as head of a pro-Nazi government. However, the overwhelming reception caused him to change course and absorb Austria into the Reich. On 13 March Seyss-Inquart announced the abrogation of Article 88 of the Treaty of Saint-Germain, which prohibited the unification of Austria and Germany, and approved the replacement of the Austrian states with Reichsgaue.[51] The seizure of Austria demonstrated once again Hitler's aggressive territorial ambitions, and, once again, the failure of the British and the French to take action against him for violating the Versailles Treaty. Their lack of will emboldened him toward further aggression.[54]

Hitler's journey through Austria became a triumphal tour that climaxed in Vienna on 15 March 1938, when around 200,000 cheering German Austrians gathered around the Heldenplatz (Square of Heroes) to hear Hitler say that "The oldest eastern province of the German people shall be, from this point on, the newest bastion of the German Reich"[55] followed by his "greatest accomplishment" (completing the annexing of Austria to form a Greater German Reich) by saying "As leader and chancellor of the German nation and Reich I announce to German history now the entry of my homeland into the German Reich."[56][57] Hitler later commented: "Certain foreign newspapers have said that we fell on Austria with brutal methods. I can only say: even in death they cannot stop lying. I have in the course of my political struggle won much love from my people, but when I crossed the former frontier (into Austria) there met me such a stream of love as I have never experienced. Not as tyrants have we come, but as liberators."[58]

Hitler said as a personal note to the Anschluss: "I, myself, as Führer and Chancellor, will be happy to walk on the soil of the country that is my home as a free German citizen."[59][60]

Hitler's popularity reached an unprecedented peak after he fulfilled the Anschluss because he had completed the long-awaited idea of a Greater Germany. Bismarck had not chosen to include Austria in his 1871 reunification of Germany, and there was genuine support from Germans in both Austria and Germany for an Anschluss.[53]

Popularity of the Anschluss

Hitler's forces suppressed all opposition. Before the first German soldier crossed the border, Heinrich Himmler and a few SS officers landed in Vienna to arrest prominent representatives of the First Republic, such as Richard Schmitz, Leopold Figl, Friedrich Hillegeist, and Franz Olah. During the few weeks between the Anschluss and the plebiscite, authorities rounded up Social Democrats, Communists, other potential political dissenters, and Austrian Jews, and imprisoned them or sent them to concentration camps. Within a few days of 12 March, 70,000 people had been arrested. The disused northwest railway station in Vienna was converted into a makeshift concentration camp.[61] American historian Evan Burr Bukey warned that the plebiscite result needs to be taken with "great caution".[62] The plebiscite was subject to large-scale Nazi propaganda and to the abrogation of the voting rights of around 360,000 people (8% of the eligible voting population), mainly political enemies such as former members of left-wing parties and Austrian citizens of Jewish or Gypsy origin.[63][64][65][62]

The Austrians' support for the Anschluss was ambivalent; but, since the Social Democratic Party of Austria leader Karl Renner and the highest representative of the Roman Catholic church in Austria Cardinal Theodor Innitzer both endorsed the Anschluss, approximately two-thirds of Austrians could be counted on to vote for it.[62] What the result of the plebiscite meant for the Austrians will always be a matter of speculation. Nevertheless, historians generally agree that it cannot be explained exclusively by simply either opportunism or the desire of socioeconomics and represented the genuine German nationalist feeling in Austria during the interwar period.[66] Also, the general anti-Semitic consensus in Austria meant that a substantial amount of Austrians were more than ready to "fulfill their duty" in the "Greater German Reich".[67] How many Austrians behind closed doors were against the Anschluss remains unknown, but only one "unhappy face" of an Austrian in public when the Germans marched into Austria has ever been produced.[68] According to some Gestapo reports, only a quarter to a third of Austrian voters in Vienna were in favour of the Anschluss.[69] According to Evan Burr Bukey, no more than one-third of Austrians ever fully supported Nazism during the existence of the Third Reich.[70]

The newly installed Nazis, within two days, transferred power to Germany, and Wehrmacht troops entered Austria to enforce the Anschluss. The Nazis held a controlled plebiscite (Volksabstimmung) in the whole Reich within the following month, asking the people to ratify the fait accompli, and claimed that 99.7561% of the votes cast in Austria were in favor.[71][72]

Although the Allies were committed to upholding the terms of the Treaty of Versailles and those of St. Germain, which specifically prohibited the union of Austria and Germany, their reaction was only verbal and moderate. No military confrontation took place, and even the strongest voices against the annexation, particularly Fascist Italy, France, and Britain (the "Stresa Front") remained at peace. The loudest verbal protest was voiced by the government of Mexico.[73]

Actions against the Jews

The campaign against the Jews began immediately after the Anschluss. They were driven through the streets of Vienna, their homes and shops were plundered. Jewish men and women were forced to wash away pro-independence slogans painted on the streets of Vienna ahead of the failed 13 March plebiscite.[74] Jewish actresses from the Theater in der Josefstadt were forced to clean toilets by the SA. The process of Aryanisation began, and Jews were driven out of public life within months.[75] These events reached a climax in the Kristallnacht pogrom of 9–10 November 1938. All synagogues and prayer houses in Vienna were destroyed, as well as in other Austrian cities such as Salzburg. The Stadttempel was the sole survivor due to its location in a residential district which prevented it from being burned down. Most Jewish shops were plundered and closed. Over 6,000 Jews were arrested overnight, the majority deported to Dachau concentration camp in the following days.[76] The Nuremberg Laws applied in Austria from May 1938, later reinforced with innumerable anti-Semitic decrees. Jews were gradually robbed of their freedoms, blocked from almost all professions, shut out of schools and universities, and forced to wear the Yellow badge from September 1941.[77]

The Nazis dissolved Jewish organisations and institutions, hoping to force Jews to emigrate. Their plans succeeded—by the end of 1941, 130,000 Jews had left Vienna, 30,000 of whom went to the United States. They left behind all of their property, but were forced to pay the Reich Flight Tax, a tax on all émigrés from Nazi Germany; some received financial support from international aid organisations so that they could pay this tax. The majority of the Jews who had stayed in Vienna eventually became victims of the Holocaust. Of the more than 65,000 Viennese Jews who were deported to concentration camps, fewer than 2,000 survived.[78]

Plebiscite

The Anschluss was given immediate effect by legislative act on 13 March, subject to ratification by a plebiscite. Austria became the province of Ostmark, and Seyss-Inquart was appointed governor. The plebiscite was held on 10 April and officially recorded a support of 99.7% of the voters.[65]

While historians concur that the votes were accurately counted, the process was neither free nor secret. Officials were present directly beside the voting booths and received the voting ballot by hand (in contrast to a secret vote where the voting ballot is inserted into a closed box). In some remote areas of Austria, people voted to preserve the independence of Austria on 13 March (in Schuschnigg's planned but cancelled plebiscite) despite the Wehrmacht's presence. For instance, in the village of Innervillgraten, a majority of 95% voted for Austria's independence.[79] However, in the plebiscite on 10 April, 73.3% of votes in Innervillgraten were in favor of the Anschluss, which was still the lowest number of all Austrian municipalities.[80] Although there is no doubt that the plebiscite result was manipulated and rigged, there was unquestionably a lot of genuine support for Hitler for carrying out the Anschluss.[81]

Austria remained part of Germany until the end of World War II. A provisional Austrian government declared the Anschluss "null und nichtig" (null and void) on 27 April 1945.[citation needed] Henceforth, Austria was recognized as a separate country, although it remained divided into occupation zones and controlled by the Allied Commission until 1955, when the Austrian State Treaty restored its sovereignty.

Banking and assets

Germany, which had a shortage of steel and a weak balance of payments, gained iron ore mines in the Erzberg and 748 million RM in the reserves of Austria's central bank Oesterreichische Nationalbank, more than twice its own cash.[51] In the years that followed, some bank accounts were transferred from Austria to Germany as "enemy property accounts".[82]

Reactions to the Anschluss

Austria in the first days of Nazi Germany's control had many contradictions: at one and the same time, Hitler's regime began to tighten its grip on every aspect of society, beginning with mass arrests as thousands of Austrians tried to escape; yet other Austrians cheered and welcomed the German troops entering their territory.

In March 1938 the local Gauleiter of Gmunden, Upper Austria, gave a speech to the local Austrians and told them in plain terms that all "traitors" of Austria were to be thrown into the newly opened concentration camp at Mauthausen-Gusen.[83] The camp became notorious for its cruelty and barbarism. During its existence an estimated 200,000 people died, half of whom were directly killed.[83]

The antigypsy sentiment was implemented initially most harshly in Austria when between 1938-1939 the Nazis arrested around 2,000 Gypsy men who were sent to Dachau and 1,000 Gypsy women who were sent to Ravensbrück.[84] Starting in 1939, Austrian Gypsies had to register themselves to local authorities.[85] The Nazis began to publish articles linking the Gypsies with criminality.[85] Until 1942, the Nazis had made a distinction between "pure Gypsies" and "Gypsy Mischlinges.[86] However, Nazi racial research claimed that 90% of Gypsies were of mixed ancestry. Subsequently, the Nazis ordered that the Gypsies were to be treated on the same level as the Jews.[86]

Many Austrian political figures announced their support of the Anschluss and their relief that it happened without violence. Cardinal Theodor Innitzer (a political figure of the CS) declared as early as 12 March: "The Viennese Catholics should thank the Lord for the bloodless way this great political change has occurred, and they should pray for a great future for Austria. Needless to say, everyone should obey the orders of the new institutions." The other Austrian bishops followed suit some days later. Vatican Radio, however, broadcast a strong denunciation of the German action, and Cardinal Pacelli, the Vatican Secretary of State, ordered Innitzer to report to Rome. Before meeting the Pope, Innitzer met Pacelli, who had been outraged by Innitzer's statement. He told Innitzer to retract his statement; he was made to sign a new statement, issued on behalf of all the Austrian bishops, that stated: "The solemn declaration of the Austrian bishops... was clearly not intended to be an approval of something that was not and is not compatible with God's law".[citation needed] The Vatican newspaper reported that the German bishops' earlier statement had been issued without approval from Rome.

Robert Kauer, president of the minority Lutheran Church in Austria, greeted Hitler on 13 March as "saviour of the 350,000 German Protestants in Austria and liberator from a five-year hardship".[citation needed] Karl Renner, the most famous Social Democrat of the First Republic, announced his support for the Anschluss and appealed to all Austrians to vote in favour of it on 10 April.[79]

The international response to the Anschluss was publicly moderate. The Times commented that 300 years before, Scotland had joined England as well and that this event would not really differ much. On 14 March, the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain spoke about the "Austrian situation" in the House of Commons. He noted that the British ambassador in Berlin objected to the use of "coercion, backed by force" that would undermine Austria's independence.[87] Within this speech Chamberlain also said, "The hard fact is that nothing could have arrested what has actually happened [in Austria] unless this country and other countries had been prepared to use force."[88]

The subdued reaction to the Anschluss (the U.S. issued a similar statement) led to Hitler's conclusion that he could use more aggressive tactics in his "roadmap" to expand Nazi Germany, as he would later do in annexing the Sudetenland.[citation needed]

On 18 March 1938, the German government communicated to the Secretary General of the League of Nations about the inclusion of Austria.[89] And next day in Geneva, the Mexican Delegate to the International Office of Labor, Isidro Fabela, voiced an energetic protest, stronger than that expressed by European countries,[90] denouncing the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany.[91][92]

Legacy

Anschluss: annexation or union?

The word Anschluss is properly translated as "joinder," "connection," "unification," or "political union." In contrast, the German word Annektierung (military annexation) was not, and is not commonly used now, to describe the union of Austria and Germany in 1938. The word Anschluss had been widespread before 1938 describing an incorporation of Austria into Germany. Calling the incorporation of Austria into Germany an "Anschluss," that is a "unification" or "joinder," was also part of the propaganda used in 1938 by Nazi Germany to create the impression that the union was not coerced. Hitler described the incorporation of Austria as a Heimkehr, a return to its original home.[93] The word Anschluss has endured since 1938, despite being a euphemism for what took place.

Some sources, like the Encyclopædia Britannica, describe the Anschluss as an "annexation"[94] rather than a union.

Changes in Central Europe

The Anschluss was among the first major steps in Austrian-born Hitler's desire to create a Greater German Reich that was to include all ethnic Germans and all the lands and territories that the German Empire had lost after the First World War. Although Austria was predominantly ethnically German and had been part of the Holy Roman Empire until it dissolved in 1806 and the German Confederation[95] until 1866 after the defeat in the Austro-Prussian War, it had never been a part of the German Empire. The unification of Germany brought about by Otto von Bismarck created that Prussian-dominated entity in 1871, with Austria, Prussia's rival for dominance of the German states, explicitly excluded.[96]

Prior to annexing Austria in 1938, Nazi Germany had remilitarized the Rhineland, and the Saar region was returned to Germany after 15 years of occupation through a plebiscite. After the Anschluss, Hitler targeted Czechoslovakia, provoking an international crisis which led to the Munich Agreement in September 1938, giving Nazi Germany control of the industrial Sudetenland, which had a predominantly ethnic German population. In March 1939, Hitler then dismantled Czechoslovakia by recognising the independence of Slovakia and making the rest of the nation a protectorate. That same year, Memelland was returned from Lithuania.

With the Anschluss, the Republic of Austria ceased to exist as an independent state. At the end of World War II, a Provisional Austrian Government under Karl Renner was set up by conservatives, Social Democrats and Communists on 27 April 1945 (when Vienna had already been occupied by the Red Army). It cancelled the Anschluss the same day and was legally recognized by the Allies in the following months. In 1955 the Austrian State Treaty re-established Austria as a sovereign state.

Second Republic

Moscow Declaration

The Moscow Declaration of 1943, signed by the United States, the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom, included a "Declaration on Austria", which stated:

The governments of the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and the United States of America are agreed that Austria, the first free country to fall a victim to Hitlerite aggression, shall be liberated from German domination.

They regard the annexation imposed on Austria by Germany on 15 March 1938, as null and void. They consider themselves as in no way bound by any changes effected in Austria since that date. They declare that they wish to see re-established a free and independent Austria and thereby to open the way for the Austrian people themselves, as well as those neighbouring States which will be faced with similar problems, to find that political and economic security which is the only basis for lasting peace.

Austria is reminded, however, that she has a responsibility, which she cannot evade, for participation in the war at the side of Hitlerite Germany, and that in the final settlement account will inevitably be taken of her own contribution to her liberation.[97][98]

The declaration was mostly intended to serve as propaganda aimed at stirring Austrian resistance. Although some Austrians aided Jews and are counted as Righteous Among the Nations, there never was an effective Austrian armed resistance of the sort found in other countries under German occupation.

However, other occupied countries, such as Norway, Poland and France, had no such requirements to forcibly provide troops to the Wehrmacht, and their resistance movements had virtually the entire male populace of those countries, to call upon. Also, even the extremely few men, untouched by conscription in Austria, who might make up a resistance movement, would certainly know that they would probably be killing fellow Austrians, forced into German service, with each and every resistance movement attack.

The Moscow Declaration is said to have a somewhat complex drafting history.[99] At Nuremberg, Arthur Seyss-Inquart[100] and Franz von Papen,[101] in particular, were both indicted under count one (conspiracy to commit crimes against peace) specifically for their activities in support of the Austrian Nazi Party and the Anschluss, but neither was convicted of this count. In acquitting von Papen, the court noted that his actions were in its view political immoralities but not crimes under its charter. Seyss-Inquart was convicted of other serious war crimes, most of which took place in Poland and the Netherlands, was sentenced to death and executed.

Austrian identity and the "victim theory"

After World War II many Austrians sought comfort in the idea of Austria as being the first victim of the Nazis. Although the Nazi party was promptly banned, Austria did not have the same thorough process of denazification that was imposed on Germany. Lacking outside pressure for political reform, factions of Austrian society tried for a long time to advance the view that the Anschluss was only an annexation at the point of a bayonet.[102]

This view of the events of 1938 has deep roots in the 10 years of Allied occupation and the struggle to regain Austrian sovereignty: the "victim theory" played an essential role in the negotiations for the Austrian State Treaty with the Soviets, and by pointing to the Moscow Declaration, Austrian politicians heavily relied on it to achieve a solution for Austria different from the division of Germany into separate Eastern and Western states. The state treaty, alongside the subsequent Austrian declaration of permanent neutrality, marked important milestones for the solidification of Austria's independent national identity during the course of the following decades.[103]

As Austrian politicians of the left and right attempted to reconcile their differences to avoid the violent conflict that had dominated the First Republic, discussions of both Austrian Nazism and Austria's role during the Nazi-era were largely avoided. Still, the Austrian People's Party (ÖVP) had advanced, and still advances, the argument that the establishment of the Dollfuss dictatorship was necessary to maintain Austrian independence. On the other hand, the Austrian Social Democratic Party (SPÖ) argues that the Dollfuss dictatorship stripped the country of the democratic resources necessary to repel Hitler; yet it ignores the fact that Hitler himself was a native of Austria.[104]

It has also helped the Austrians develop their own national identity as before. After World War II and the fall of Nazi Germany the political ideology of Pan-Germanism fell into disfavor and is now seen by the majority of German-speaking people as taboo.[citation needed] Unlike earlier in the 20th century when there was no Austrian identity separate from a German one, in 1987 only 6% of the Austrians identified themselves as "Germans."[105] A survey carried out in 2008 found that 82% of Austrians considered themselves to be their own nation.[106]

Political events

For decades, the victim theory remained largely undisputed in Austria. The public was rarely forced to confront the legacy of Nazi Germany. One of those occasions arose in 1965, when Taras Borodajkewycz, a professor of economic history, made anti-Semitic remarks following the death of Ernst Kirchweger, a concentration camp survivor killed by a right-wing protester during riots. It was not until the 1980s that Austrians confronted their mixed past on a large scale. The catalyst for the Vergangenheitsbewältigung (struggle to come to terms with the past) was the Waldheim affair. Kurt Waldheim, a candidate in the presidential election and former UN Secretary-General, was accused of having been a member of the Nazi party and of the infamous SA (he was later absolved of direct involvement in war crimes). The Waldheim affair started the first serious discussions about Austria's past and the Anschluss.

Another factor was the rise of Jörg Haider and the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) in the 1980s. The party had combined elements of the pan-German right with free-market liberalism since its foundation in 1955, but after Haider ascended to the party chairmanship in 1986, the liberal elements became increasingly marginalized. Haider began to openly use nationalist and anti-immigrant rhetoric. He was criticised for using the völkisch (ethnic) definition of national interest ("Austria for Austrians") and his apologetics for Austria's past, notably calling members of the Waffen-SS "men of honour". Following a dramatic rise in electoral support in the 1990s that peaked in the 1999 elections, the FPÖ entered a coalition with the Austrian People's Party (ÖVP), led by Wolfgang Schüssel. This was condemned in 2000. The coalition prompted the regular Donnerstagsdemonstrationen (Thursday demonstrations) in protest against the government, which took place on the Heldenplatz where Hitler had greeted the masses during the Anschluss. Haider's tactics and rhetoric, often criticised as sympathetic to Nazism, forced Austrians to reconsider their relationship to the past. Haider's coalition partner, former Chancellor Wolfgang Schüssel, in a 2000 interview with The Jerusalem Post, reiterated the "first victim" theory.[107]

Literature

The political discussions and soul-searching were reflected in other aspects of culture. Thomas Bernhard's last play, Heldenplatz (1988), generated controversy even before it was produced, fifty years after Hitler's entrance to the city. Bernhard made the historic elimination of references to Hitler's reception in Vienna emblematic of Austrian attempts to claim its history and culture under questionable criteria. Many politicians called Bernhard a Nestbeschmutzer (damaging the reputation of his country) and openly demanded that the play should not be staged in Vienna's Burgtheater. Waldheim, still president, called the play "a crude insult to the Austrian people".[108]

Historical Commission and outstanding legal issues

In the Federal Republic of Germany the Vergangenheitsbewältigung ("struggle to come to terms with the past") has been partially institutionalised in literary, cultural, political, and educational contexts. Austria formed a Historikerkommission[109] ("Historian's Commission" or "Historical Commission") in 1998 with a mandate to review Austria's role in the Nazi expropriation of Jewish property from a scholarly rather than legal perspective, partly in response to continuing criticism of its handling of property claims. Its membership was based on recommendations from various quarters, including Simon Wiesenthal and Yad Vashem. The Commission delivered its report in 2003.[110] Noted Holocaust historian Raul Hilberg refused to participate in the Commission and in an interview he stated his strenuous objections in terms both personal and in reference to larger questions about Austrian culpability and liability, comparing what he thought to be relative inattention by the World Jewish Congress to the settlement governing the Swiss bank holdings of those who died or were displaced by the Holocaust.[111]

The Simon Wiesenthal Center continues to criticise Austria (as recently as June 2005) for its alleged historical and ongoing unwillingness aggressively to pursue investigations and trials against Nazis for war crimes and crimes against humanity from the 1970s onwards. Its 2001 report offered the following characterization:

Given the extensive participation of numerous Austrians, including at the highest levels, in the implementation of the Final Solution and other Nazi crimes, Austria should have been a leader in the prosecution of Holocaust perpetrators over the course of the past four decades, as has been the case in Germany. Unfortunately relatively little has been achieved by the Austrian authorities in this regard and in fact, with the exception of the case of Dr. Heinrich Gross which was suspended this year under highly suspicious circumstances (he claimed to be medically unfit, but outside the court proved to be healthy) not a single Nazi war crimes prosecution has been conducted in Austria since the mid-1970s.[112]

In 2003, the Center launched a worldwide effort named "Operation: Last Chance" in order to collect further information about those Nazis still alive that are potentially subject to prosecution. Although reports issued shortly thereafter credited Austria for initiating large-scale investigations, there has been one case where criticism of Austrian authorities arose recently: The Center put 92-year-old Croatian Milivoj Asner on its 2005 top ten list. Asner fled to Austria in 2004 after Croatia announced it would start investigations in the case of war crimes he may have been involved in. In response to objections about Asner's continued freedom, Austria's federal government deferred to either extradition requests from Croatia or prosecutorial actions from Klagenfurt, claiming reason of dementia in 2008. Milivoj Ašner died on 14 June 2011 at the age of 98 in his room in a Caritas nursing home still in Klagenfurt.

Austrian political and military leaders in Nazi Germany

|

See also

|

Fictional depictions:

|

References

Informational notes

- ^ After the Prussian-dominated German nation-state was created in 1871 without Austria, the German question was still very active in most parts of the ethnic German lands of the Austro-Hungarian and German empires; the Austrian pan-Germans were in favour of a Pan-German vision of Austria joining Germany in order to create a "Greater Germany" and the Germans inside the German Empire were in favour of all Germans being unified into a single state.[2]

- ^ Hitler was an ethnic German, but was not a German citizen by birth since he had been born in the Austro-Hungarian empire. He gave up his Austrian citizenship in 1925 and remained stateless for seven years before he became a German citizen in 1932.[19]

Citations

- ^ Anschluss Archived 21 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine PONS Online Dictionary

- ^ Low 1974, p. 3.

- ^ Bukey 2002, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Shirer 1984.

- ^ Blackbourn 1998, pp. 160–175.

- ^ Sheehan, James J. (1993). German History, 1770–1866. Oxford University Press. p. 851. ISBN 9780198204329.

- ^ Taylor 1990, p. 25.

- ^ Suppan (2008). ′Germans′ in the Habsburg Empire. pp. 171–172.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Unowsky 2005, p. 157.

- ^ Giloi 2011, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Low 1974, pp. 14–16.

- ^ Gould, S. W. (1950). "Austrian Attitudes toward Anschluss: October 1918 – September 1919". Journal of Modern History. 22 (3): 220–231. doi:10.1086/237348. JSTOR 1871752. S2CID 145392779.

- ^ Stackelberg 1999, p. 194.

- ^ Low 1976, p. 7.

- ^ Compare for example Wilson's Fourteen Points: "X. The people of Austria-Hungary, whose place among the nations we wish to see safeguarded and assured, should be accorded the freest opportunity to autonomous development."

- ^ Staff (14 September 1919) Preuss Denounces Demand of Allies, The New York Times

- ^ David Walker, "Industrial Location in Turbulent Times: Austria through Anschluss and Occupation," Journal of Historical Geography (1986) 12#2 pp 182–195

- ^ Taylor 2001, p. 257.

- ^ Lemons, Everette O. (2005). The Third Reich, A Revolution of Ideological Inhumanity. Vol. Volume I "The Power of Perception". CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-4116-1932-6. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Kershaw 2008, p. 75.

- ^ Stackelberg 2007, p. 9.

- ^ Mitcham, Samuel (1996) Why Hitler?: The Genesis of the Nazi Reich p.67

- ^ Kershaw 2008, p. 87.

- ^ Hamann, Brigitte (2010) Hitler's Vienna: A Portrait of the Tyrant as a Young Man. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. p.107 ISBN 9781848852778

- ^ Hitler, Adolf (June 2010). Mein Kampf. Bottom of the Hill. ISBN 978-1-935785-07-1.

- ^ Staff (17 January 1919) "Divide on German Austria; Centrists Favor Union, but Strong Influences Oppose It", The New York Times

- ^ Zeman 1973, pp. 137–142.

- ^ a b c Gunther, John (1936). Inside Europe. Harper & Brothers. pp. 284–285, 317–318.

- ^ Rosmus, Anna (2015) Hitlers Nibelungen, Samples Grafenau pp.53f

- ^ Shirer 1990, p. 296.

- ^ a b Overy, Richard (1999) "Germany and the Munich Crisis: A Mutilated Victory?" in Lukes, Igor and Goldstein, Rick (eds.) The Munich Crisis, 1938 London: Frank Cass. p.200

- ^ a b c Kershaw 2001, p. 67.

- ^ a b Kershaw 2001, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b c Kershaw 2001, p. 68.

- ^ Kershaw 2001, p. 45.

- ^ Messerschmidt, Manfred “Foreign Policy and Preparation for War” from Germany and the Second World War pages 636–637

- ^ Carr, William Arms, Autarchy and Aggression pages 73–78.

- ^ a b c Weinberg 1981, p. 46.

- ^ Faber 2009, pp. 108–118.

- ^ John A. Leopold, "Seyss-Inquart and the Austrian Anschluss," Historian (1986) 30#2 pp 199–218.

- ^ MacDonogh 2009, p. 35.

- ^ Price, G. Ward (1939). Year of Reckoning. London: Cassell. p. 92.

- ^ Faber 2009, pp. 121–124.

- ^ a b "Hitler Triumphant: Early Diplomatic Triumphs". 12 November 2010.

- ^ a b CBS World Roundup Broadcast 13 March 1938 Columbia Broadcasting System retrieved from http://otr.com/ra/news/CBS_Roundup_3-13-1938.mp3

- ^ Nazis Take Austria, The History Place, retrieved from http://www.historyplace.com/worldwar2/triumph/tr-austria.htm

- ^ See 'Vienna, 1938', in Hans Keller, 1975: 1984 minus 9, Dennis Dobson, 1977, p. 28 Mayerhofer (1998). "Österreichs Weg zum Anschluss im März 1938" (in German). Wiener Zeitung Online. Retrieved 11 March 2007. Detailed article on the events of the Anschluss, in German.

- ^ ORT, World. "Music and the Holocaust".

- ^ Albert Speer recalled the Austrians cheering approval as cars of Germans entered what had once been an independent Austria. Speer (1997), p.109

- ^ W. Carr, Arms, Autarky and Aggression: A study in German Foreign Policy, 1933–1939, (Southampton, 1981) p.85.

- ^ a b c MacDonogh, Giles (2009). 1938. Basic Books. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0-465-02012-6.

- ^ Surprised or not, Hitler’s schoolboy dream of a "greater Germany" had come to fruition when Austria was incorporated into the Reich. Ozment (2005), p.274.

- ^ a b Stackelberg 1999, p. 170.

- ^ Hildebrand (1973), pp.60-61

- ^ Liulevicius, Vejas Gabriel (2009). The German Myth of the East: 1800 to the Present. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 184. ISBN 9780191610462.

- ^ Original German: "Als Führer und Kanzler der deutschen Nation und des Reiches melde ich vor der deutschen Geschichte nunmehr den Eintritt meiner Heimat in das Deutsche Reich."

- ^ "Video: Hitler proclaims Austria's inclusion in the Reich (2 MB)". Retrieved 11 March 2007.

- ^ "Anschluss". Archived from the original on 21 June 2005.

- ^ Giblin, James (2002). The Life and Death of Adolf Hitler. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 110. ISBN 0-395-90371-8.

- ^ Toland, John (2014). Adolf Hitler: The Definitive Biography. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 450. ISBN 978-1-101-87277-2.

- ^ Staff (28 March 1938) "Austria: 'Spring Cleaning'" Time

- ^ a b c Bukey 2002, p. 38.

- ^ Staff (ndg). "Austria". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- ^ Staff (ndg). "Anschluss". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- ^ a b "Die propagandistische Vorbereitung der Volksabstimmung". Austrian Resistance Archive. 1988. Archived from the original on 4 April 2007. Retrieved 11 March 2007.

- ^ Bukey 2002, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Bukey 2002, p. 39.

- ^ Bukey 2002, p. 33.

- ^ J. Evans 2006, p. 655.

- ^ Bukey 2002, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Austria: A Country Study. Select link on left for The Anschluss and World War II. Eric Solsten, ed. (Washington, D. C.: Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, 1993).

- ^ Emil Müller-Sturmheim 99.7%: a plebiscite under Nazi rule Austrian Democratic Union London, England 1942

- ^ Österreich, Außenministerium der Republik. "Joint communiqué by Austria and Mexico on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of the Mexican protest against the "Anschluss" of Austria by Nazi Germany – BMEIA, Außenministerium Österreich".

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (2015). Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning. Crown/Archetype. pp. 77–81. ISBN 978-1101903452.

- ^ Maria Kohl, Katrin; Ritchie, Robertson (2006). A History of Austrian Literature 1918-2000. Camden House. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-57113-276-5.

- ^ McKale, Donald (2006). Hitler's Shadow War: The Holocaust and World War II. Taylor Trade Publishing. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-4616-3547-5.

- ^ Wistrich, Robert S. (1992). Austrians and Jews in the Twentieth Century: From Franz Joseph to Waldheim. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-349-22378-7.

- ^ Pauley 2000, pp. 297–98.

- ^ a b "1938: Austria". MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009. Retrieved 11 March 2007.

- ^ "Anschluss Tirols an NS-Deutschland und Judenpogrom in Innsbruck 1938".

- ^ Kershaw 2001, p. 83.

- ^ "Page 32 USACA - Property Control Branch". Fold3. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ^ a b Gellately 2002, p. 69.

- ^ Gellately 2002, p. 108.

- ^ a b Gellately 2001, p. 222.

- ^ a b Gellately 2001, p. 225.

- ^ Neville Chamberlain, "Statement of the Prime Minister in the House of Commons, 14 March 1938 Archived 25 May 2000 at archive.today."

- ^ Shirer 1984, p. 308.

- ^ Chronology of the League of Nations [1] Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Serrano Migallón, Francisco (2000) Con certera visión: Isidro Fabela y su tiempo. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica. 2000. pp. 112–113. ISBN 968-16-6049-8. In Spanish.

- ^ Kloyber, Christian: "Don Isidro Fabela: 50 años después de muerte. Recuerdo al autor de la protesta de México en contra de la "anexión" de Austria por la Alemania Nazi de 1938." 12 August 2014 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) In Spanish. Retrieved 4 September 2016.] - ^ League of Nations. Communication from the Mexican Delegation. C.101.M.53.1938.VII; 19 March 1938 [2](Note: Also available in French.) Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Manning, Jody Abigail (ndg) Austria at the Crossroads: The Anschluss and its Opponents (thesis) pp.269, 304. Cardiff UNiversity

- ^ "Anschluss". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 11 March 2007.

- ^ Heeren, Arnold Hermann Ludwig (1873), Talboys, David Alphonso (ed.), A Manual of the History of the Political System of Europe and its Colonies, London: H. G. Bohn, pp. 480–481

- ^ Erich Eyck (1958) Bismark and the German Empire New York: Norton. pp.174-187; 188-194

- ^ "Moskauer Deklaration 1943 und die alliierte Nachkriegsplanung".

- ^ Barbara Jelavich – Modern Austria: Empire and Republic, 1815–1986, Cambridge University Press 1987, p.238

- ^ Gerald Stourzh, "Waldheim's Austria", The New York Review of Books 34, no. 3 (February 1987).

- ^ "Judgment, The Defendants: Seyss-Inquart Archived 20 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine," The Nizkor Project.

- ^ "The Defendants: Von Papen Archived 20 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine," The Nizkor Project.

- ^ Beniston, Judith (2003). "'Hitler's First Victim'? — Memory and Representation in Post-War Austria: Introduction". Austrian Studies. 11: 1–13. JSTOR 27944673.

- ^ Steininger (2008)

- ^ Art 2006, p. 101.

- ^ Ernst Bruckmüller. "Die Entwicklung des Österreichbewußtseins" (PDF) (in German). Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Österreicher fühlen sich heute als Nation" (in German). 2008.

- ^ Short note on Schüssel's interview in The Jerusalem Post (in German), Salzburger Nachrichten, 11 November 2000.

- ^ Liukkonen, Petri. "Thomas Bernhard". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 17 February 2005.

- ^ Austrian Historical Commission Archived 21 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Press statement on the report of the Austrian Historical Commission Archived 11 February 2005 at the Wayback Machine Austrian Press and Information Service, 28 February 2003

- ^ Hilberg interview with the Berliner Zeitung, Archived 15 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine as quoted by Norman Finkelstein's web site.

- ^ Efraim Zuroff, "Worldwide Investigation and Prosecution of Nazi War Criminals, 2001–2002 Archived 11 February 2005 at the Wayback Machine," Simon Wiesenthal Center, Jerusalem (April 2002).

Bibliography

- Art, David (2006). The Politics of the Nazi Past in Germany and Austria. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85683-6.

- Blackbourn, David (1998). The Long Nineteenth Century: A History of Germany, 1780-1918. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507672-1.

- Bukey, Evan Burr (2002). Hitler's Austria: Popular Sentiment in the Nazi Era, 1938-1945. University North Carolina. ISBN 0807853631.

- Faber, David (2009). Munich, 1938: Appeasement and World War II. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-4992-8.

- Gellately, Robert (2002). Backing Hitler: Consent and Coercion in Nazi Germany. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192802917.

- Gellately, Robert (2001). Social Outsiders in Nazi Germany. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691086842.

- Giloi, Eva (2011). Monarchy, Myth, and Material Culture in Germany 1750-1950. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76198-7.

- Hildebrand, Klaus (1973) The Foreign Policy of the Third Reich. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press

- J. Evans, Richard (2006). The Third Reich in Power, 1933-1939. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-100976-6.

- Kershaw, Ian (2001). Hitler 1936-1945: Nemesis. Penguin. ISBN 0140272399.

- Low, Alfred D. (1974). The Anschluss Movement, 1918–1919: And the Paris Peace Conference. American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-103-3.

- Low, Alfred D. (1976). "The Anschluss Movement (1918–1938) in Recent Historical Writing: German Nationalism and Austrian Patriotism". Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism. 3 (2).

- MacDonogh, Giles (2009). 1938: Hitler's Gamble. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-1-84901-212-6.

- Ozment, Steven (2005) A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People. New York: Harper Perennial.

- Pauley, Bruce F. (2000). From Prejudice to Persecution: A History of Austrian Anti-Semitism. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-6376-3.

- Shirer, William L. (1990). Rise And Fall Of The Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671728687.

- Shirer, William L. (1984). Twentieth Century Journey, Volume 2, The Nightmare Years: 1930–1940. Boston: Little, Brown & Company. ISBN 0-316-78703-5.

- Speer, Albert (1997) Inside the Third Reich. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Stackelberg, Roderick (1999). Hitler's Germany: Origins, Interpretations, Legacies. Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0415201152.

- Stackelberg, Roderick (2007). The Routledge Companion to Nazi Germany. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-39386-2.

- Steininger, Wolf (2008) Austria, Germany, and the Cold War: from the Anschluss to the State Treaty 1938–1955 New York: Berghahn Books.ISBN 978-1-84545-326-8

- Taylor, A. J. P. (2001). The Course of German History: A Survey of the Development of German History Since 1815. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-52196-8.

- Taylor, A. J. P. (1990). The Habsburg Monarchy 1809-1918: A History of the Austrian Empire and Austria-Hungary. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-0-14-193238-5.

- Unowsky, Daniel L. (2005). The Pomp and Politics of Patriotism: Imperial Celebrations in Habsburg Austria, 1848-1916. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-400-2.

- Weinberg, Gerhard (1981). The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany Starting World War II. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226885119.

- Zeman, Zbynek (1973). Nazi Propaganda. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192850601.

Further reading

- Barnett, William P., and Michael Woywode. "From Red Vienna to the Anschluss: Ideological Competition among Viennese Newspapers during the Rise of National Socialism," American Journal of Sociology (2004) 109#6 pp. 1452–1499 in JSTOR

- Bukey, Evan Burr. Hitler's Hometown: Linz, Austria, 1908–1945 (Indiana University Press, 1986) ISBN 0-253-32833-0.

- Gehl, Jürgen. Austria, Germany, and the Anschluss, 1931–1938 (1963), the standard scholarly monograph online.

- Luža, Radomir. Austro-German Relations in the Anschluss Era (1975) ISBN 0691075689.

- Parkinson, F., ed. Conquering the Past: Austrian Nazism Yesterday and Today (Wayne State University Press, 1989). ISBN 0-8143-2054-6.

- Pauley, Bruce F. Hitler and the Forgotten Nazis: A History of Austrian National Socialism (University of North Carolina Press, 1981) ISBN 0-8078-1456-3.

- Rathkolb, Oliver. "The 'Anschluss' in the Rear-View Mirror, 1938–2008: Historical Memories Between Debate and Transformation," Contemporary Austrian Studies (2009), Vol. 17, pp. 5–28, historiography.

- Suppan, Arnold (2019). "The Anschluss of Austria". Hitler–Beneš–Tito: National Conflicts, World Wars, Genocides, Expulsions, and Divided Remembrance in East-Central and Southeastern Europe, 1848–2018. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. pp. 345–372. ISBN 978-3-7001-8410-2. JSTOR j.ctvvh867x.

- Wright, Herbert. "The Legality of the Annexation of Austria by Germany," American Journal of International Law (1944) 38#4 pp. 621–635 in JSTOR

- Gedye, George Eric Rowe. Betrayal in Central Europe. Austria and Czechoslovakia, the Fallen Bastions. New and revised edition. Harper & Brothers, New York 1939. Paperback reissue, Faber & Faber, 2009. ISBN 978-0571251896.

- Schuschnigg, Kurt. The brutal takeover: The Austrian ex-Chancellor's account of the Anschluss of Austria by Hitler (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971) ISBN 0-297-00321-6.

External links

- The Crisis Year of 1934 Buchner, A. From the Destruction of the Socialist Lager to National Socialist Coup Attempt (accessed 10 June 2005).

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum – Library Bibliography: Anschluss

- Austrian Historical Commission

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Anschluss article

- BBC article by Robert Knight, who served on the Historikercommission

- Full text of the Moscow Declaration

- Simon Wiesenthal Center

- Time magazine coverage of the events of the Anschluss

- Pictures of Adolf Hitler in Vienna

- Anschluss – a soundbite history of the German invasion into Austria

- Map of Europe at time of Anschluss at omniatlas.com

- 1938 in Austria

- 1938 in Germany

- 1938 in international relations

- Annexation

- Austria–Germany military relations

- German nationalism in Austria

- Jewish Austrian history

- Invasions by Germany

- Invasions of Austria

- National unifications

- Nazi terminology

- Vergangenheitsbewältigung

- March 1938 events

- Austria under National Socialism