History of Zanzibar

| History of Tanzania |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| Pre-colonial period |

| Colonial period |

| Modern history |

|

|

People have lived in Zanzibar for 20,000 years.[citation needed] History properly starts when the islands became a base for traders voyaging between the African Great Lakes, the Somali Peninsula, the Arabian peninsula, Iran, and the Indian subcontinent. Unguja offered a protected and defensible harbor, so although the archipelago had few products of value, Omanis and Yemenis settled in what became Zanzibar City (Stone Town) as a convenient point from which to trade with towns on the Swahili Coast. They established garrisons on the islands and built the first mosques in the African Great Lakes Region.

During the Age of Exploration, the Portuguese Empire was the first European power to gain control of Zanzibar, and kept it for nearly 200 years. In 1698, Zanzibar fell under the control of the Sultanate of Oman, which developed an economy of trade and cash crops, with a ruling Arab elite and a Bantu general population. Plantations were developed to grow spices; hence, the moniker of the Spice Islands (a name also used for the Dutch colony the Moluccas, now part of Indonesia). Another major trade good was ivory, the tusks of elephants that were killed on the Tanganyika mainland - a practice that is still in place to this day. The third pillar of the economy was slaves, which gave Zanzibar an important place in the Indian Ocean slave trade, the Indian Ocean equivalent of the better-known Triangular Trade. The Omani Sultan of Zanzibar controlled a substantial portion of the African Great Lakes coast, known as Zanj, as well as extensive inland trading routes.

Sometimes gradually, sometimes by fits and starts, control of Zanzibar came into the hands of the British Empire. In 1890, Zanzibar became a British protectorate. The death of one sultan and the succession of another of whom the British did not approve later led to the Anglo-Zanzibar War, also known as the shortest war in history.

The islands gained independence from Britain in December 1963 as a constitutional monarchy. A month later, the bloody Zanzibar Revolution, in which several thousand Arabs and Indians were killed and thousands more expelled and expropriated, led to the formation of the People's Republic of Zanzibar. That April, the republic merged with the mainland Tanganyika, or more accurately, was subsumed into Tanzania, of which Zanzibar remains a semi-autonomous region. Recent decades in Zanzibar have seen political violence related to contested elections, with a major massacre in 2001.

Prehistory

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

Zanzibar has been inhabited, perhaps not continuously, since the Paleolithic period. A 2005 excavation at Kuumbi Cave in southeastern Zanzibar found heavy duty stone tools that showed occupation of the site at least 22,000 years ago.[1] Archaeological discoveries of a limestone cave used radiocarbon techniques to prove more recent occupation, from around 2800 BC to the year 1 AD (Chami 2006). Traces of the communities include objects such as glass beads from around the Indian Ocean. It is a suggestion of early trans-oceanic trade networks, although some writers have expressed doubt about this possibility.

No cave sites on Zanzibar have revealed pottery fragments used by early and later Bantu farming and iron-working communities who lived on the islands (Zanzibar, Mafia) during the first millennium AD. On Zanzibar, the evidence for the later farming and iron-working communities dating from the mid-first millennium AD is much stronger and indicates the beginning of urbanism there when settlements were built with mud-timber structures (Juma 2004). This is somewhat earlier than the existing evidence for towns in other parts of the Swahili Coast, given as the 9th century AD. The first permanent residents of Zanzibar seem to have been the ancestors of the Hadimu and Tumbatu, who began arriving from the African Great Lakes mainland around 1000 AD. They had belonged to various Bantu ethnic groups from the mainland, and on Zanzibar they lived in small villages and failed to coalesce to form larger political units. Because they lacked central organization, they were easily subjugated by outsiders.

Early Trade Routes

Ancient pottery demonstrates existing trade routes with Zanzibar as far back as the ancient Sumer and Assyria.[2] An ancient pendant discovered near Eshnunna dated ca. 2500-2400 BC. has been traced to copal imported from the Zanzibar region.[3]

Traders from Arabia (mostly Yemen), the Persian Gulf region of Iran (especially Shiraz), and west India probably visited Zanzibar as early as the 1st century AD, followed by Somalis during the Middle Ages with the emergence of Islam. They used the monsoon winds to sail across the Indian Ocean and landed at the sheltered harbor located on the site of present-day Zanzibar Town. Although the islands had few resources of interest to the traders, they offered a good location from which to make contact and trade with the towns of the Swahili Coast. A phase of urban development associated with the introduction of stone material to the construction industry of the African Great Lakes littoral began from the 10th century AD.

Traders began to settle in small numbers on Zanzibar in the late 11th or 12th century, intermarrying with the indigenous Africans. Eventually a hereditary ruler (known as the Mwenyi Mkuu or Jumbe), emerged among the Hadimu, and a similar ruler, called the Sheha, was set up among the Tumbatu. Neither had much power, but they helped solidify the ethnic identity of their respective peoples.

The Yemenis built the earliest mosque in the southern hemisphere in Kizimkazi, the southernmost village in Unguja. A kufic inscription on its mihrab bears the date AH 500, i.e. 1107 AD.[4]

Villages were also present in which lineage groups were common.[citation needed]

Portuguese rule

Vasco da Gama's visit in 1499 marked the beginning of European influence. In 1503 or 1504, Zanzibar became part of the Portuguese Empire when Captain Ruy Lourenço Ravasco Marques landed and demanded and received tribute from the sultan[who?] in exchange for peace.[5] Zanzibar remained a possession of Portugal for almost two centuries.

Zanzibar Sultanate

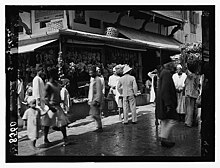

In 1698, Zanzibar fell under the control of the Sultan of Oman. The Portuguese were expelled and a lucrative trade in slaves (started decades earlier by the Portuguese to supply the West Indies), and ivory thrived, along with an expanding plantation economy centring on cloves. With an excellent harbor and no shortage of fresh water, Stone Town (capital of Zanzibar) became one of the largest and wealthiest cities in East Africa. Under Omani rule, all of the most fertile land was handed over to Omani aristocrats who enslaved the farmers who worked the land. Every year, hundreds of dhows would sail across the Indian Ocean from Arabia, Persia and India with the monsoon winds blowing in from the northeast, bringing iron, cloth, sugar and dates. When the monsoon winds shifted to the southwest in March or April, the traders would leave, with their ships packed full of tortoiseshell, copal, cloves, coir, coconuts, rice, ivory, and slaves.[6]

The Arabs established garrisons at Zanzibar, Pemba, and Kilwa. The height of Arab rule came during the reign of Sultan Seyyid Said (more fully, Sayyid Said bin Sultan al-Busaid), who in 1840 moved his capital from Muscat, Oman, to Stone Town. He established a ruling Arab elite and encouraged the development of clove plantations, using the island's slave labour. Zanzibar's commerce fell increasingly into the hands of traders from the Indian subcontinent, whom Said encouraged to settle on the island. After his death in 1856, his sons struggled over the succession. On April 6, 1861, Zanzibar and Oman were divided into two separate principalities. Sayyid Majid bin Said Al-Busaid (1834/5–1870), his sixth son, became the Sultan of Zanzibar, while the third son, Sayyid Thuwaini bin Said al-Said, became the Sultan of Oman.

Accounts by visitors to Zanzibar often emphasize the outward beauty of the place. The British explorer Richard Francis Burton described Zanzibar in 1856 as: "Earth, sea and sky, all seemed wrapped in a soft and sensuous repose...The sea of purist sapphire, which had not parted with its blue rays to the atmosphere...lay looking...under a blaze of sunshine which touched every object with a dull burnish of gold". Adding to the beauty were the gleaming white minarets of mosques and the sultan's palaces in Stone Town, making the city appear from the distance to Westerners as an "Orientalist" fantasy brought to life. Those who got closer described Stone Town as an extremely foul-smelling city that reeked of human and animal excrement, garbage and rotting corpses as garbage, sewage and bodies of animals and slaves were all left out in the open to rot. The British explorer Dr. David Livingstone when living in Stone Town in 1866 wrote in his diary: "The stench arising from a mile and a half or two square miles of exposed sea beach, which is the general depository of the filth of the town is quite horrible...It might be called Stinkabar rather than Zanzibar". Besides for the pervasive foul odor of Stone Town, accounts by visitors described a city full of slaves on the brink of starvation and a place where cholera, malaria, and venereal diseases all flourished.[6]

Of all the forms of economic activity on Zanzibar, slavery was the most profitable and all the blacks living on the island were Bantu people taken from the mainland. The slaves were brought to Zanzibar in dhows, where many as possible were packed in with no regard for comfort or safety. Many did not survive the journey to Zanzibar. Upon reaching Zanzibar, the slaves were stripped completely naked, cleaned, had their bodies covered with coconut oil, and forced to wear gold and silver bracelets bearing the name of the slave trader. At that point, the slaves were forced to march nude in a line down the streets of Stone Town guarded by loyal slaves of the slavers carrying swords or spears until someone would show interest in the procession.[7] A captain from a ship owned by the East India Company who visited Zanzibar in 1811 and witnessed these marches wrote about how a buyer examined the slaves:

The mouth and teeth are inspected, and afterwards every part of the body in succession, not even excepting the breasts, etc, of the girls, many of whom I have seen examined in the most indecent manner in the public market by the purchasers...The slave is then made to walk or run a little way to show that there is no defect about the feet; after which, if the price is agreed to, they are stripped of their finery and delivered over to their future master. I have frequently counted twenty or thirty of these files in the market at one time...Women with children newly born hanging at their breasts and others so old they can scarcely walk, are sometimes seen dragged about in this manner. They had in general a very dejected look; some groups appeared so ill fed that their bones seemed as if ready to penetrate the skin.[7]

Every year, about 40,000-50,000 slaves were taken to Zanzibar. About a third went to work on clove and coconut plantations of Zanzibar and Pemba while the rest were exported to Persia, Arabia, the Ottoman Empire and Egypt. Conditions on the plantations were so harsh that about 30% of the male slaves died every year, thus maintaining the demand for more slaves. The Omani Arabs who ruled Zanzibar had in the words of the American diplomat Donald Petterson a "culture of violence" where brute force was the preferred solution to problems and outlandish cruelty was a virtue. The ruling al-Busaid family was characterized by fratricidal quarrels as it was common for brother to murder brother, and this was typical of the Arab aristocracy, where it was acceptable for family members to murder one another to gain land, wealth, titles, and slaves. Visitors to Zanzibar often mentioned the "shocking brutality" which the Arab masters treated their slaves, who were so cowed into submission that there was never a slave revolt attempted on Zanzibar. The cruelty which the Arab masters treated their slaves left behind a legacy of hate, which exploded in the revolution of 1964.[7]

The Sultan of Zanzibar controlled a large portion of the African Great Lakes Coast, known as Zanj, as well as trading routes extending much further across the continent, as far as Kindu on the Congo River. In November 1886, a German-British border commission established the Zanj as a ten-nautical mile (19 km) wide strip along most of the African Great Lakes coast, stretching from Cape Delgado (now in Mozambique) to Kipini (now in Kenya), including Mombasa and Dar es Salaam, and several offshore Indian Ocean islands. However, from 1887 to 1892, all of these mainland possessions were lost to the colonial powers of the United Kingdom, Germany, and Italy, with Britain gaining control of Mombasa in 1963.

In the late 1800s, the Omani Sultan of Zanzibar also briefly claimed to control Mogadishu in the Horn and southern Somalia. However, power on the ground remained in the hands of a powerful Somali kingdom, the Geledi Sultanate (which, also holding sway over the Jubba River and Shebelle region in Somalia's interior, was at its zenith).[8] In 1892, Geledi ruler: Osman Ahmed leased the city to Italy. The Italians eventually purchased the executive rights in 1905, and made Mogadishu the capital of the newly established Italian Somaliland.[9]

Zanzibar was famous worldwide for its spices and its slaves. During the 19th century, Zanzibar was known all over the world in the words of Petterson as: "A fabled land of spices, a vile center of slavery, a place of origins of expeditions into the vast, mysterious continent, the island was all these things during its heyday in the last half of the 19th century.[10] It was the main slave-trading port of the African Great Lakes region, and in the 19th century as many as 50,000 slaves were passed through the slave markets of Zanzibar each year.[11] (David Livingstone estimated that 80,000 new slaves died each year before ever reaching the island.) Tippu Tip was the most notorious slaver, under several sultans, and also a trader, plantation owner, and governor. Zanzibar's spices attracted ships from as far away as the United States, which established a consulate in 1837. The United Kingdom's early interest in Zanzibar was motivated by both commerce and the determination to end the slave trade.[12] In 1822, the British signed the first of a series of treaties with Sultan Said to curb this trade. Under strong British pressure, the slave trade was officially abolished in 1876, but slavery itself remained legal in Zanzibar until 1897.[7]

Zanzibar had the distinction of having the first steam locomotive in the African Great Lakes region, when Sultan Bargash bin Said ordered a tiny 0-4-0 tank engine to haul his regal carriage from town to his summer palace at Chukwani. One of the most famous palaces built by the Sultans was the House of Wonders, which is today one of Zanzibar's most popular tourist attractions.

British influence and rule

The British Empire gradually took over; the relationship was formalized by the 1890 Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty, in which Germany pledged, among other things, not to interfere with British interests in Zanzibar. This treaty made Zanzibar and Pemba a British protectorate (not colony), and the Caprivi Strip (in what is now Namibia) part of German South West Africa. British rule through a sultan (vizier) remained largely unchanged.

The death of Hamad bin Thuwaini on 25 August 1896 saw the Khalid bin Bargash, eldest son of the second sultan, Barghash ibn Sa'id, take over the palace and declare himself the new ruler. This was contrary to the wishes of the British government, which favoured Hamoud bin Mohammed. This led to a showdown, later called the Anglo-Zanzibar War, on the morning of 27 August, when ships of the Royal Navy destroyed the Beit al Hukum Palace, having given Khalid a one-hour ultimatum to leave. He refused, and at 9 am the ships opened fire. Khalid's troops returned fire and he fled to the German consulate. A cease fire was declared 45 minutes after the action had begun, giving the bombardment the title of The Shortest War in History. Hamoud was declared the new ruler and peace was restored once more. Acquiescing to British demands, he brought an end in 1897 to Zanzibar's role as a centre for the centuries-old eastern slave trade by banning slavery and freeing the slaves, compensating their owners. Hamoud's son and heir apparent, Ali, was educated in Britain.

From 1913 until independence in 1963, the British appointed their own residents (essentially governors). One of the more appreciated reforms brought in by the British were the establishment of a proper sewer, garbage disposal system and burial system so that the beaches of Zanzibar reeked no more of bodies, excrement and garbage, finally eliminating the foul smell of Stone Town, which had repulsed so many Western visitors.[13]

Independence and revolution

On 10 December 1963, Zanzibar received its independence from the United Kingdom as a constitutional monarchy under the Sultan. This state of affairs was short-lived, as the Sultan and the democratically elected government were overthrown on 12 January 1964 in the Zanzibar Revolution led by John Okello, a Ugandan citizen who organized and led the revolution with his followers on the island. Sheikh Abeid Amani Karume was named president of the newly created People's Republic of Zanzibar. Several thousand ethnic Arab (5,000-12,000 Zanzibaris of Arabic descent) and Indian civilians were murdered and thousands more detained or expelled, their property either confiscated or destroyed. The film Africa Addio documents the violence and massacre of unarmed ethnic Arab civilians.

The revolutionary government nationalized the local operations of the two foreign banks in Zanzibar, Standard Bank and National and Grindlays Bank. These nationalized operations may have provided the foundation for the newly created Peoples Bank of Zanzibar. Jetha Lila, the one locally owned bank in Zanzibar, closed. It was owned by Indians and although the revolutionary government of Zanzibar urged it to continue functioning, the loss of its customer base as Indians left the island made it impossible to continue.

One of the main impacts of the revolution in Zanzibar was to break the power of the Arab/Asian ruling class, who had held it for around 200 years.[14][15] Despite the merger with Tanganyika, Zanzibar retained a Revolutionary Council and House of Representatives which was, until 1992, run on a one-party system and has power over domestic matters.[16] The domestic government is led by the President of Zanzibar, Karume being the first holder of this office. This government used the success of the revolution to implement reforms across the island. Many of these involved the removal of power from Arabs. The Zanzibar civil service, for example, became an almost entirely African organisation, and land was redistributed from Arabs to Africans.[14] The revolutionary government also instituted social reforms such as free healthcare and opening up the education system to African students (who had occupied only 12% of secondary school places before the revolution).[14]

The government sought help from the Soviet Union, the German Democratic Republic (GDR), and P. R. China for funding for several projects and military advice.[14] The failure of several GDR-led projects including the New Zanzibar Project, a 1968 urban redevelopment scheme to provide new apartments for all Zanzibaris, led to Zanzibar focussing on Chinese aid.[17][18] The post-revolution Zanzibar government was accused of draconian controls on personal freedoms and travel and exercised nepotism in appointments to political and industrial offices, the new Tanzanian government being powerless to intervene.[19][20] Dissatisfaction with the government came to a head with the assassination of Karume on 7 April 1972, which was followed by weeks of fighting between pro and anti-government forces.[21] A multi-party system was eventually established in 1992, but Zanzibar remains dogged by allegations of corruption and vote-rigging, though the 2010 general election was seen to be a considerable improvement.[16][22][23]

The revolution itself remains an event of interest for Zanzibaris and academics. Historians have analysed the revolution as having a racial and a social basis with some stating that the African revolutionaries represent the proletariat rebelling against the ruling and trading classes, represented by the Arabs and South Asians.[24] Others discount this theory and present it as a racial revolution that was exacerbated by economic disparity between races.[25]

Within Zanzibar, the revolution is a key cultural event, marked by the release of 545 prisoners on its tenth anniversary and by a military parade on its 40th.[26] Zanzibar Revolution Day has been designated as a public holiday by the government of Tanzania; it is celebrated on 12 January each year.[27]

Union with Tanganyika

On 26 April 1964, the mainland colony of Tanganyika united with Zanzibar to form the United Republic of Tanganyika and Zanzibar; this lengthy name was compressed into a portmanteau, the United Republic of Tanzania, on 29 October 1964. After unification, local affairs were controlled by President Abeid Amani Karume, while foreign affairs were handled by the United Republic in Dar es Salaam. Zanzibar remains a semi-autonomous region of Tanzania.

The autonomous status of Zanzibar is viewed as comparable to Hong Kong as suggested by some scholars, and being recognized as the "African Hong Kong".[28]

The Zanzibar House of Representatives was established in 1980. Prior to this, the Revolutionary Council held both the executive and legislative functions for 16 years following the Zanzibar Revolution in 1964.[29]

21st century

There are many political parties in Zanzibar, but the most popular parties are the Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) and the Civic United Front (CUF). Since the early 1990s, the politics of the archipelago have been marked by repeated clashes between these two parties. The results of the past elections held under the multiparty system are as follows:[30]

| Political Party | Election Year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | ||||||

| Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) | 26 | 34 | 30 | |||||

| Civic United Front (CUF) | 24 | 16 | 19 | |||||

| Total | 50 | 50 | 50 | |||||

Contested elections in October 2000 led to a massacre on 27 January 2001 when, according to Human Rights Watch, the army and police shot into crowds of protestors, killing at least 35 and wounding more than 600. Those forces, accompanied by ruling party officials and militias, also went on a house-to-house rampage, indiscriminately arresting, beating, and sexually abusing residents. Approximately 2,000 temporarily fled to Kenya.[31]

Violence erupted again after another contested election on 31 October 2005, with the CUF claiming that its rightful victory had been stolen from it. Nine people were killed.[32][33]

Following 2005, negotiations between the two parties aiming at the long-term resolution of the tensions and a power-sharing accord took place, but they suffered repeated setbacks. The most notable of these took place in April 2008, when the CUF walked away from the negotiating table following a CCM call for a referendum to approve of what had been presented as a done deal on the power-sharing agreement.[34]

In November 2009, the then-president of Zanzibar, Amani Abeid Karume, met with CUF secretary-general Seif Sharif Hamad at the State House to discuss how to save Zanzibar from future political turmoil and to end the animosity between them.[35] This move was welcomed by many, including the United States.[36] It was the first time since the multi-party system was introduced in Zanzibar that the CUF agreed to recognize Karume as the legitimate president of Zanzibar.[35]

A proposal to amend Zanzibar's constitution to allow rival parties to form governments of national unity was adopted by 66.2 percent of voters on 31 July 2010.[37]

Nowadays,The Alliance for Change and Transparency-Wazalendois (ACT-Wazalendo) is considered the main opposition political party of semi-autonomous Zanzibar. The constitution of Zanzibar requires the party that comes in second in the polls to join a coalition with the winning party. ACT-Wazalendo joined a coalition government with the islands’ ruling party Chama Cha Mapinduzi in December 2020 after Zanzibar disputed elections.[38]

Lists of rulers

Sultans of Zanzibar

- Majid bin Said (1856–1870)

- Barghash bin Said (1870–1888)

- Khalifah bin Said (1888–1890)

- Ali bin Said (1890–1893)

- Hamad bin Thuwaini (1893–1896)

- Khalid bin Barghash (1896)

- Hamud bin Muhammed (1896–1902)

- Ali bin Hamud (1902–1911) (abdicated)

- Khalifa bin Harub (1911–1960)

- Abdullah bin Khalifa (1960–1963)

- Jamshid bin Abdullah (1963–1964)

Viziers

- Sir Lloyd William Matthews, (1890 to 1901)

- A.S. Rogers, (1901 to 1906)

- Arthur Raikes, (1906 to 1908)

- Francis Barton, (1906 to 1913)

British residents

- Francis Pearce, (1913 to 1922)

- John Sinclair, (1922 to 1923)

- Alfred Hollis, (1923 to 1929)

- Richard Rankine, (1929 to 1937)

- John Hall, (1937 to 1940)

- Henry Pilling, (1940 to 1946)

- Vincent Glenday, 1946 to 1951)

- John Rankine, (1952 to 1954)

- Henry Steven Potter, (1955 to 1959)

- Arthur George Mooring, (1959 to 1963)

See also

References

- ^ "Excavations at Kuumbi Cave on Zanzibar 2005", The African Archaeology Network: Research in Progress, Paul Sinclair (Uppsala University), Abdurahman Juma, Felix Chami, 2006

- ^ Ingrams, William Harold (1967). Zanzibar, its history and its people. Routledge. pp. 43–46. ISBN 0-7146-1102-6.

- ^ Meyer, Carol; Joan Markley Todd; Curt W. Beck (1991). "From Zanzibar to Zagros: A Copal Pendant from Eshnunna". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 50 (4): 289–298. doi:10.1086/373516. JSTOR 545490. S2CID 161728895.

- ^ Fay, Robert (2005-04-07), "Swahili People", African American Studies Center, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.43544, ISBN 978-0-19-530173-1

- ^ Ingrams, W. H. (1 June 1967). Zanzibar: Its History and Its People. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780714611020 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Petterson, Don. Revolution In Zanzibar An American's Cold War Tale. New York: Westview, 2002. pp. 6-8.

- ^ a b c d Petterson, pages 23-24.

- ^ Lewis, I. M. (1988). A Modern History of Somalia: Nation and State in the Horn of Africa. Westview Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-8133-7402-4.

- ^ Hamilton, Janice (1 January 2007). Somalia in Pictures. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-8225-6586-4.

- ^ Petterson, page 4

- ^ National Geographic article

- ^ Remembering East African slave raids BBC

- ^ Petterson, Donald Revolution In Zanzibar An American Cold War's Tale, New York: Westview, 2002 page 7.

- ^ a b c d Triplett 1971, p. 612

- ^ Speller 2007, p. 1

- ^ a b Sadallah, Mwinyi (23 January 2006), "Revert to single party system, CUF Reps say", The Guardian, archived from the original on 2 August 2007, retrieved 14 April 2009.

- ^ Myers 1994, p. 453

- ^ Triplett 1971, p. 613

- ^ Triplett 1971, p. 614

- ^ Triplett 1971, p. 616

- ^ Said, Salma (8 April 2009), "Thousand attend Karume memorial events in Zanzibar", The Citizen, Tanzania, retrieved 14 April 2009[permanent dead link].

- ^ Freedom House (2008), Freedom in the World – Tanzania, retrieved 5 April 2012

- ^ Freedom House (2011), Freedom in the World – Tanzania, retrieved 5 April 2012

- ^ Kuper 1971, pp. 87–88

- ^ Kuper 1971, p. 104

- ^ Kalley, Schoeman & Andor 1999, p. 611

- ^ Commonwealth Secretariat (2005), Tanzania, archived from the original on 1 December 2008, retrieved 10 February 2009

- ^ Simon Shen, One country, two systems: Zanzibar, Ming Pao Weekly, Sep 2016.

- ^ "History of the ZHoR". Zanzibar House of Representatives. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ "Elections in Zanzibar". Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ "Tanzania: Zanzibar Election Massacres Documented". Human Rights Watch. 10 April 2002. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ "Nine killed in Zanzibar election violence", Seattle Times, reported by Chris Tomlinson, The Associated Press, 1 November 2005 Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "karelprinsloo karel prinsloo". karelprinsloo karel prinsloo.

- ^ "Tanzanian Affairs » ZANZIBAR – A BIG DISAPPOINTMENT".

- ^ a b "Karume: No elections next year in Zanzibar if…", Zanzibar Institute for Research and Public Policy, reported by Salma Said, reprinted from an original article in The Citizen, 19 November 2009

- ^ "Welcome to VPP Zanzibar, Tanzania". United States Virtual Presence Post. U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 2011-02-03. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ "Zanzibar: 2010 Constitutional referendum results" Archived 2016-01-05 at the Wayback Machine, Electoral Institute for the Sustainability of Democracy in Africa, updated August 2010.

- ^ "Zanzibar's opposition party to join coalition government". Associated Press. 6 December 2020.

Sources

- Kalley, Jacqueline Audrey; Schoeman, Elna; Andor, Lydia Eve (1999), Southern African Political History, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-313-30247-3.*Kuper, Leo (1971), "Theories of Revolution and Race Relations", Comparative Studies in Society and History, 13 (1): 87–107, doi:10.1017/S0010417500006125, JSTOR 178199, S2CID 145769109.

- Myers, Garth A. (1994), "Making the Socialist City of Zanzibar", Geographical Review, 84 (4): 451–464, doi:10.2307/215759, JSTOR 215759.

- Petterson, D. (2002) Revolution In Zanzibar: An American's Cold War Tale, New York: Westview. ISBN 0813342686

- Speller, Ian (2007), "An African Cuba? Britain and the Zanzibar Revolution, 1964.", Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 35 (2): 1–35, doi:10.1080/03086530701337666, S2CID 159656717.

- Triplett, George W. (1971), "Zanzibar: The Politics of Revolutionary Inequality", The Journal of Modern African Studies, 9 (4): 612–617, doi:10.1017/S0022278X0005285X, JSTOR 160218, S2CID 153484206.

External links

- Excerpt from: Race, Revolution and the Struggle for Human Rights in Zanzibar by Thomas Burgess

- Edward Steere (1869), Some account of the town of Zanzibar (1st ed.), London: Charles Cull, Wikidata Q19046291