2014 Scottish independence referendum

Should Scotland be an independent country? |

| This article is part of a series within the Politics of the United Kingdom on the |

| Politics of Scotland |

|---|

|

A referendum on whether Scotland should be an independent country will take place on Thursday 18 September 2014.[2] Following an agreement between the Scottish Government and the United Kingdom Government,[3] the Scottish Independence Referendum Bill, setting out the arrangements for this referendum, was put forward on 21 March 2013,[4] passed by the Scottish Parliament on 14 November 2013 and received Royal Assent on 17 December 2013.[5][6] The question to be asked in the referendum will be "Should Scotland be an independent country?" as recommended by the Electoral Commission.[7]

The principal issues in the referendum are the economic strength of Scotland and whether the rest of the UK will agree to share the pound sterling, defence arrangements, continued relations with the rest of the UK, and membership of supranational organisations, particularly the European Union (EU) and NATO.

History

Scotland and England united to form the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707, by virtue of the Acts of Union. Prior to this, the Kingdom of Scotland had been a sovereign state for over 800 years.

Devolution referendums

A proposal for Scottish devolution was put to a referendum in 1979, but resulted in no change, despite a narrow majority of votes cast being in favour of change,[8] due to a clause requiring that the number voting 'Yes' had to exceed 40% of the total electorate.[8] No further constitutional reform was proposed under the Conservative Thatcher and Major governments between 1979 and 1997. Soon after Labour returned to power in 1997, a second Scottish devolution referendum was held.[9] Clear majorities expressed support for both a devolved Scottish Parliament and that Parliament having the power to vary the basic rate of income tax.[9] The Scotland Act 1998 established the new Scottish Parliament, first elected on 6 May 1999.[10]

2007 SNP administration

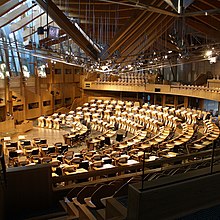

A commitment to hold a referendum in 2010 was part of the Scottish National Party (SNP)'s election manifesto when it contested the 2007 Scottish Parliament election.[11][dead link] As a result of that election, it became the largest party in the Scottish Parliament, the legislative assembly established in 1999 for dealing with unreserved matters within Scotland, and formed a minority government led by the First Minister, Alex Salmond.[12] The SNP administration accordingly launched a 'National Conversation' as a consultation exercise in August 2007, part of which included a draft of a referendum bill, as the Referendum (Scotland) Bill.[12][13]

After the National Conversation was concluded, a white paper for the proposed Referendum Bill was published on 30 November 2009.[14][15] The paper detailed four possible scenarios, with the text of the Bill and Referendum to be revealed later.[14] The scenarios were: no change; devolution per the Calman Review; further devolution; and full independence.[14] The Scottish Government published a draft version of the bill on 25 February 2010 for public consultation.[16][17] The 84-page document was titled Scotland's Future: Draft Referendum (Scotland) Bill Consultation Paper and contained a consultation document and a draft version of the bill.[18] The consultation paper set out the proposed ballot papers, the mechanics of the proposed referendum, and how the proposed referendum was to be regulated.[18] Public responses were invited from 25 February to 30 April.[19]

The bill outlined three proposals: the first was full devolution or 'devolution max', suggesting that the Scottish Parliament should be responsible for "all laws, taxes and duties in Scotland", with the exception of "defence and foreign affairs; financial regulation, monetary policy and the currency", which would be retained by the British Government.[18] The second proposal outlined Calman-type fiscal reform, gaining the additional powers and responsibilities of setting a Scottish rate of income tax that could vary by up to 10p in the pound compared to the rest of the UK, setting the rate of stamp duty land tax and "other minor taxes", and introducing new taxes in Scotland with the agreement of the UK Parliament, and finally, "limited power to borrow money."[18] The third proposal was for full independence, stating that the Scottish Parliament would gain the power to convert Scotland into a country that would "have the rights and responsibilities of a normal, sovereign state."[18]

In the third Scottish Parliament, only 50 of 129 MSPs (47 SNP, 2 Greens, and Margo McDonald) supported a referendum.[20][21] The Scottish Government eventually opted to withdraw the bill after failing to secure opposition support.[12][22]

2011 SNP administration

The SNP repeated its commitment to hold an independence referendum when it published its election manifesto for the 2011 Scottish parliamentary election.[23] Days before the election, First Minister Salmond stated that legislation for a referendum would be proposed in the "second half of the parliament", as he wanted to secure more powers for the Scottish Parliament via the Scotland Bill first.[24] The SNP gained an overall majority in the election, winning 69 of the 129 seats available, thereby gaining a mandate to hold an independence referendum.[25][26]

In January 2012, the UK Government offered to legislate to provide the Scottish Parliament with the specific powers to hold a referendum, providing it was "fair, legal and decisive".[26] This would set "terms of reference for the referendum", such as its question(s), elector eligibility and which body would organise the vote.[27] As the UK Government worked on legal details, including the timing of the vote, Salmond announced an intention to hold the referendum in the autumn of 2014.[27] Negotiations continued between the two governments until October 2012, when the Edinburgh Agreement was reached.[12]

The Scottish Independence Referendum (Franchise) Act 2013 was passed by the Scottish Parliament on 27 June 2013 and received Royal Assent on 7 August 2013.[28]

On 15 November 2013, the Scottish Government published Scotland's Future, a 670-page white paper laying out the case for independence and the means through which Scotland might become an independent country.[29] Salmond described it as the "most comprehensive blueprint for an independent country ever published", and argued it showed his government "do[es] not seek independence as an end in itself, but rather as a means to changing Scotland for the better".[29] The leader of the Better Together campaign, Alistair Darling, described it as being "thick with false promises and meaningless assertions. Instead of a credible and costed plan, we have a wish-list of political promises without any answers on how Alex Salmond would pay for them."[29]

Administration

Date and eligibility

The Scottish Government announced on 21 March 2013 that the referendum would be held on 18 September 2014.[2] Some media reports mentioned that 2014 would be the 700th anniversary of the Battle of Bannockburn[30][31] and that Scotland will also host the 2014 Commonwealth Games and the 2014 Ryder Cup.[31] Salmond admitted that the presence of these events made 2014 a "good year to hold a referendum".[32]

Under the terms of the 2010 Draft Bill, the following people would be entitled to vote in the referendum:[18]

- British citizens who are resident in Scotland;

- citizens of the 53 other Commonwealth countries who are resident in Scotland;

- citizens of the 27 other European Union countries who are resident in Scotland;

- members of the House of Lords who are resident in Scotland;

- Service/Crown personnel serving in the UK or overseas in the British Armed Forces or with Her Majesty's Government who are registered to vote in Scotland.

The Scottish Government has passed legislation to reduce the voting age for the referendum from 18 to 16, as it is SNP policy to reduce the voting age for all elections in Scotland.[18][33][34] The move was supported by Labour, the Liberal Democrats, and the Scottish Greens.[35][36] 16 has been the age of legal capacity in Scotland since the Age of Legal Capacity (Scotland) Act 1991.

In January 2012, Elaine Murray MSP of Labour led a debate arguing that the franchise should be extended to Scots living outside Scotland, including the approximately 800,000 Scots living in the other parts of the UK.[37] This was opposed by the Scottish Government, which argued that it would greatly increase the complexity of the referendum and stated that there was evidence from the United Nations Human Rights Committee that other nations "might question the legitimacy of a referendum if the franchise is not territorial".[37]

In the House of Lords, Baroness Symons argued that the rest of the UK should be allowed to vote on Scottish independence, on the grounds that it would affect the whole country. This argument was rejected by the British Government, as the Advocate General for Scotland Lord Wallace said that "whether or not Scotland should leave the United Kingdom is a matter for Scotland".[37] Wallace also pointed to the fact that only two of 11 referendums since 1973 had been across all of the United Kingdom.[37] Professor John Curtice has also argued the Northern Ireland sovereignty referendum, 1973, created a precedent for allowing only those resident in one part of the UK to vote on its sovereignty.[38]

Legality

Prior to the scheduling of the 2014 referendum, there had been debate as to whether the Scottish Parliament had the power to legislate for a referendum relating to the issue of Scottish independence without a Section 30 Order. Under the current system of devolution, the Scottish Parliament does not have the power to unilaterally secede from the United Kingdom, because the constitution is a reserved matter for the parliament of the United Kingdom.[20] The Scottish Government insisted in 2010 that they could legislate for a referendum, as it would be an "advisory referendum on extending the powers of the Scottish Parliament",[19] whose result would "have no legal effect on the Union."[18]: 17

In January 2012, Lord Wallace, Advocate General for Scotland, expressed the opinion that the holding of any referendum concerning the constitution would be outside the legislative power of the Scottish Parliament[26][39] and that private individuals could challenge a Scottish Parliament referendum bill.[40] The UK Parliament has the power to transfer legal authority to the Scottish Parliament to prevent this, but the Scottish Government initially objected to the attachment of conditions to any referendum by this process.[40] The two governments eventually signed the Edinburgh Agreement, which allowed the temporary transfer of legal authority. The agreement states that the governments "agreed to promote an Order in Council under Section 30 of the Scotland Act 1998 in the United Kingdom and Scottish Parliaments to allow a single-question referendum on Scottish independence to be held before the end of 2014. The Order will put it beyond doubt that the Scottish Parliament can legislate for that referendum."[3]

Oversight

As agreed in the Edinburgh Agreement, the Electoral Commission is responsible for overseeing the referendum, "with the exception of the conduct of the poll and announcement of the result, and the giving of grants. In its role of regulating the campaign and campaign spending, the Electoral Commission will report to the Scottish Parliament. [...] The poll and count will be managed in the same way as [...local] elections, by local returning officers [...] and directed by a Chief Counting Officer."[3]

Question

The Edinburgh Agreement stated that the wording of the question would be decided by the Scottish Parliament and reviewed by the Electoral Commission for intelligibility.[3]

The Scottish Government stated that its preferred question was "Do you agree that Scotland should be an independent country?"[41] The Electoral Commission tested the proposed question along with three other possible versions.[42] Their research found that the "Do you agree" preface meant that it was a leading question, which would be more likely to garner a positive response.[41] The question was subsequently amended to "Should Scotland be an independent country?", which the Electoral Commission found was the most neutral and concise of the versions tested.[41][42]

The clarity and brevity of the question used in Scotland has been contrasted with the longer formulations used in the sovereignty referendums held in Quebec in 1980 and 1995.[41][43] During an election debate in Quebec, Liberal leader Philippe Couillard asked Parti Quebecois leader Pauline Marois whether she would use a "straightforward question" like the one agreed in Scotland, if there was to be another referendum in Quebec.[43]

Campaign

Campaign funding and costs

In the 2010 Draft Bill, the Scottish Government proposed that there would be a designated organisation campaigning for a 'Yes' vote and a designated organisation campaigning for a 'No' vote, both of which would be permitted to spend up to £750,000 on their campaign and be entitled to one free mailshot to every household or vote in the referendum franchise. There was to be no public funding for campaigns. Political parties were each to be allowed to spend £100,000.[18] This proposed limit on party spending was revised to £250,000 in 2012.[44]

In 2013, new proposals by the Electoral Commission were accepted; these will apply to the 16-week regulated period preceding the poll and allow for the two designated campaign organisations to spend up to £1.5 million each and for the parties in Scotland to spend the following amounts: £1,344,000 (SNP); £834,000 (Labour); £396,000 (Conservatives); £201,000 (Liberal Democrats); £150,000 (Greens).[41] An unlimited number of other organisations can register with the Electoral Commission, but their spending is limited to £150,000.[45]

According to the Scottish Government's consultation paper published on 25 February 2010, the cost of the referendum was "likely to be around £9.5 million", mostly spent on running the poll and the count. Costs would also include the posting of one neutral information leaflet about the referendum to every Scottish household, and one free mailshot to every household or voter in the poll for the designated campaign organisations.[18] As of April 2013, the projected cost of the referendum was £13.3 million.[46]

Campaign organisations

The campaign in favour of Scotland remaining in the United Kingdom, Better Together, was launched on 25 June 2012.[47] It is led by Alastair Darling, former Chancellor of the Exchequer, and has support from the Labour Party, Conservative Party and Liberal Democrats.[47]

The campaign in favour of Scottish independence, Yes Scotland, was launched on 25 May 2012.[48] Its chief executive is Blair Jenkins,[48] formerly the Director of Broadcasting at STV and Head of News and Current Affairs at both STV and BBC Scotland. The campaign is supported by the SNP,[48] the Scottish Green Party (which also created "its own pro-independence campaign to run alongside Yes Scotland"[49]) and the Scottish Socialist Party. Its launch featured a number of celebrities and urged Scots to sign a declaration of support for independence.[48] Salmond stated that he hoped one million people in Scotland would sign the declaration.[50] By 24 May 2013, the number of signatories had reached 372,103.[51]

Issues

Agriculture

As part of a European Union (EU) member state, Scottish farmers presently receive subsidies from the EU under the Common Agriculture Policy (CAP).[52] A total of £583 million in subsidy payments were made to Scottish farmers in 2013.[52] This funding is paid by the EU to the UK, which then determines how much to allocate to each of the devolved administrations, including Scotland.[53] In the last CAP agreement, farmers in the UK qualified for additional convergence payments because their productivity was more than 10% below the EU average, mainly due to the mountainous terrain in Scotland.[53] Supporters of independence therefore believe that an independent Scotland would receive greater agricultural subsidies than at present.[53] Opponents of independence believe that Scottish farmers benefit from being part of a state (the UK) that is one of the larger EU member states and therefore has a greater say in CAP negotiations.[53] They also question whether an independent Scotland would immediately receive full subsidy payments from the EU, as other states which have recently joined have had their subsidies phased in.[53]

Border controls and immigration

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2014) |

The UK has some exceptions to EU regulations. One such exception is the opt-out from the Schengen Area, meaning there are full passport check for travellers from other EU countries, except Ireland. The UK and Ireland are part of a Common Travel Area (CTA), which means there are no passport checks on the Irish border. An independent Scotland would need to negotiate the right to be outside the Schengen Area, otherwise passport controls would be needed at the Anglo–Scottish border. The white paper on independence, Scotland's Future, proposes that an independent Scotland would join the CTA.[54] Alistair Carmichael, the Secretary of State for Scotland, said in January 2014 that it would make sense for Scotland to be in the CTA, but it would have to operate similar immigration policies to the rest of the UK.[54] This position was supported by Home Secretary Theresa May, who said in March 2014 that passport checks would be introduced if Scotland adopted a looser immigration policy.[54]

Childcare

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2014) |

In its white paper on independence, Scotland's Future, the Scottish Government pledged to expand childcare provision.

Citizenship

The Scottish Government proposes that all Scottish-born British citizens would automatically become Scottish citizens on the date of independence, regardless of whether or not they are then living in Scotland. British citizens "habitually resident" in Scotland will also be considered Scottish citizens, even if they already hold the citizenship of another country. Every person who would automatically be considered a Scottish citizen will be able to opt out of Scottish citizenship, if they so wish, provided they already hold the citizenship of another country.[55] The Scottish Government also proposes that anyone with a Scottish parent or grandparent will be able to apply for registration as a Scottish citizen, and any foreign national living in Scotland legally, or who has lived in Scotland for at least 10 years at any time and has an ongoing connection to Scotland, shall be able to apply for naturalisation as a Scottish citizen.[55] The UK Home Secretary, Theresa May, said future policies of an independent Scottish Government would affect whether Scottish citizens would be allowed to retain British citizenship.[56]

Defence

Budget

In July 2013, the SNP proposed that there would be a £2.5 billion annual military budget in an independent Scotland.[57] The House of Commons Defence Select Committee—composed of Conservative, Labour, Liberal Democrat, and Democratic Unionist MPs[58]—criticised the SNP's proposals and argued that the £2.5bn budget was too low.[59] On the air defence plans it stated: "We do not currently understand how the Scottish Government expects, within the available budget, to mount a credible air defence—let alone provide the additional transport, rotary wing and other support aircraft an air force would need."[59] It also warned of the impact of independence on the Scottish defence industry: "This impact would be felt most immediately by those companies engaged in shipbuilding, maintenance, and high end technology. The requirements of a Scottish defence force would not generate sufficient domestic demand to compensate for the loss of lucrative contracts from the UK MoD, and additional security and bureaucracy hurdles would be likely to reduce competitiveness with UK based companies."[60] Andrew Murrison, UK Minister for International Security Strategy agreed with the Committee that the budget was too low and said it was "risible" for the SNP to suggest it could create an independent force by "salami-slicing" units from the British armed forces that are based in Scotland, or have Scottish links.[61]

The Royal United Services Institute suggested in October 2012 that an independent Scotland could set up a Scottish Defence Force, comparable in size and strength to those of other small European states like Denmark, Norway and Ireland, at a cost of £1.8 billion per annum, "markedly lower" than the £3.3 billion contributed by Scottish taxpayers to the UK defence budget in the 2010/11 fiscal year. This figure was based on the assumption that such a force "would be predominantly used for domestic defence duties with the capability to contribute to coalition and alliance operations under the aegis of whatever organisations Scotland became a member of" and that therefore it "would not be equipped with expensive and state-of-the-art hardware across the board". The authors acknowledged that an independent Scotland would "need to come to some arrangement with the rest of the UK" on intelligence-gathering, cyber-warfare and cyber-defence, that the future cost of purchasing and maintaining equipment of its forces might be higher due to smaller orders, and that recruitment and training "may prove problematic" in the early years.[62]

Dorcha Lee, a former colonel in the Irish Army, has suggested that Scotland could eschew forming an army based on inherited resources from the British Army and instead follow an Irish model: form a limited self-defence force, with the capability to contribute "in the region of 1,100 personnel" overseas to peacekeeping missions, a navy with the "capacity to contribute to an international peacekeeping mission" and an air force with "troop-carrying helicopters" and "a logistics aircraft".[63] Professor Malcolm Chalmers of the Royal United Services Institute has argued that such a small force would be incompatible with the requirements of NATO membership: Irish levels of defence spending "would be difficult to sell to Scotland's NATO neighbours—including the UK—who would see it as an attempt to free-ride on their protection."[64]

The SNP have argued that there was a defence underspend of "at least £7.4 billion" between 2002 and 2012 in Scotland and that independence would allow the Scottish Government to correct this imbalance.[65] As part of a reorganization of the British Army, the UK Government confirmed in July 2013 that seven Territorial Army sites in Scotland would be closed, although army reservists in Scotland would increase from 2,300 to 3,700; the SNP stated that Scotland was suffering "disproportionate defence cuts".[66]

The Scottish Government plans that, by 2026, an independent Scotland would have a total of 15,000 regular and 5,000 reserve personnel across land, air and maritime forces.[67] According to the government's plans, on independence, Scotland's defence forces would have a total of 9,200 personnel (7,500 regular and 1,700 reserve), equipped with a negotiated share of current UK military assets. The Scottish Government's assessment of defence capabilities at the point of independence include:[68]

- a naval squadron including 2 frigates, 1 command ship, 4 mine countermeasures vessels, and 8 patrol boats;

- an all-arms brigade with three infantry/marines units, and supported by light armoured reconnaissance, light artillery, engineer, helicopter, communications, transport, logistics and medical units;

- a special forces unit;

- a squadron of 12 Eurofighter Typhoon multirole combat aircraft and tactical air transport squadron;

The Scottish Government plans that by 2021 the defence forces will have increased in strength and capability to a total of 12,030 personnel (10,350 regular and 1,680 reserve), with the addition of two additional frigates and several maritime patrol aircraft.[69]

Nuclear weapons

The Trident nuclear missile system is based at Coulport weapons depot and naval base of Faslane in the Firth of Clyde area. The SNP objects to having nuclear weapons on Scottish territory. Salmond has stated that "it is inconceivable that an independent nation of 5,250,000 people would tolerate the continued presence of weapons of mass destruction on its soil." British military leaders have claimed that there is no alternative site for the missiles.[70][71] In April 2014, several British military leaders co-signed a letter sent to the Daily Telegraph stating that forcing Trident to leave Scottish waters would place the UK nuclear deterrent in jeopardy.[72]

A seminar hosted by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace stated that the Royal Navy would have to consider a range of alternatives, including disarmament.[73] British MP Ian Davidson cited a UK report published by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament that suggested that the warheads could be deactivated within days and safely removed in 24 months.[74] A report in 2013 from the Scotland Institute think tank suggested a future Scottish Government could be convinced to lease the Faslane nuclear base to the rest of the United Kingdom to maintain good diplomatic relations and expedite NATO entry negotiations.[75]

NATO membership

The Scottish Government's position that Trident nuclear weapons should be removed from Scotland but that it should hold NATO membership has been branded as a contradiction by figures including Willie Rennie, leader of the Scottish Liberal Democrats,[76] and Patrick Harvie, co-convenor of the Scottish Green Party.[77] Alex Salmond has said it would be "perfectly feasible" to join NATO while maintaining an anti-nuclear stance and that Scotland would only pursue NATO membership "subject to an agreement that Scotland will not host nuclear weapons and NATO continues to respect the right of members to only take part in UN sanctioned operations".[78] In 2013, Professor Malcolm Chalmers of the Royal United Services Institute claimed that "pragmatists" in the SNP accepted that NATO membership would be likely to involve a long-term basing deal enabling the UK to keep Trident on the Clyde.[79]

The former NATO Secretary General and Scottish Labour peer Lord Robertson has said that Scottish independence could be "cataclysmic" for the West and that its enemies would "cheer loudest".[80] The Scotsman newspaper commented that Robertson had shown "a lack of proportion and perspective" in describing independence in this way.[81] Robertson has also said that “either the SNP accept the central nuclear role of NATO ... or they reject the nuclear role of NATO and ensure that a separate Scottish state stays out of the world's most successful defence alliance."[82] Kurt Volker, former United States Permanent Representative to NATO, has said there is likely to be "great goodwill" to an independent Scotland becoming a NATO member.[83]

At their annual conference in October 2012, SNP delegates voted to drop a long-standing policy of opposition in principle to NATO membership.[84] The Scottish Green Party and Scottish Socialist Party, which participate in the Yes Scotland campaign for independence, remain opposed to continued membership of NATO.[85] MSPs John Finnie and Jean Urquhart resigned from the SNP over the policy change.[86] Finnie said that "there is an overwhelming desire to rid Scotland of nuclear weapons and that commitment can't be made with membership of a first strike nuclear alliance", and challenged Salmond to explain "how the aim of being a member of NATO and ridding Scotland of nuclear weapons could take place".[77]

Intelligence

A UK Government paper on security stated that Police Scotland would lose access to the intelligence apparatus of the UK, including MI5, SIS and GCHQ.[87] The paper went on to say that an independent Scottish state would then need to build its own security infrastructure.[87] Home Secretary Theresa May has commented that an independent Scotland would have access to less security capability, but would not necessarily face a reduced threat.[87] In 2013, Allan Burnett, former head of intelligence with Strathclyde Police and Scotland's counter-terrorism co-ordinator until 2010, told the Sunday Herald that "an independent Scotland would face less of a threat, intelligence institutions will be readily created, and allies will remain allies". Peter Jackson, Canadian-born professor of security at the University of Glasgow, agreed that Special Branch could form a "suitable nucleus" of a Scottish equivalent of MI5, and that Scotland could forego creating an equivalent of MI6, instead "relying on pooled intelligence or diplomatic open sources" like Canada or the Nordic countries.[88] Baroness Ramsay, a Labour peer and former Case Officer with MI6, said that the Scottish Government's standpoint on intelligence was "extremely naïve" and that it was "not going to be as simple as they think".[88]

Democracy

The Scottish Government and pro-independence campaigners have argued that a "democratic deficit" exists in Scotland[89][90][91] because of the centralised nature of the UK and its lack of a codified constitution, and that this could be resolved through independence.[92] The SNP has also described the unelected House of Lords as an "affront to democracy" and said that "a Yes vote for independence means that people in Scotland can get rid of the expensive and unrepresentative Westminster tier".[93]

The "democratic deficit" label has sometimes been used to refer to the period between the 1979 and 1997 UK general elections, during which the Labour Party held a majority of Scottish seats but the Conservative Party governed the whole of the UK.[94] Alex Salmond has argued that instances such as this, where Westminster governments and parliaments implement policies which are opposed by Scottish politicians, amount to a lack of democracy, and that "the people who live and work in Scotland are the people most likely to make the right choices for Scotland".[95][96] In January 2012, Patrick Harvie said: "Greens have a vision of a more radical democracy in Scotland, with far greater levels of discussion and decision making at community level. Our hope is that the debate over independence will spark a new enthusiasm for people taking control over the future of our country and our communities."[97]

Unionists, such as Menzies Campbell, have pointed out that the democratic deficit has been addressed by creating the devolved Scottish Parliament and that several Scots have served in the government of the United Kingdom.[98] Conservative MP Daniel Kawczynski argued in 2009 that the asymmetric devolution in place in the UK has created a democratic deficit for England.[99] This deficit is more commonly known as the West Lothian question, which cites the anomaly where English MPs cannot vote on affairs devolved to Scotland, but Scottish MPs can vote on the equivalent subjects in England. Kawczynski also pointed out that the average size of a parliamentary constituency is larger in England than in Scotland.[99]

Economy

A principal issue in the referendum is the economy.[100] The UK Treasury issued a report on 20 May 2013 which said that Scotland's banking systems would be too big to ensure depositor compensation in the event of a bank failure.[101] The report indicated that Scottish banks would have assets worth 1,254% of GDP, which is more than Cyprus and Iceland before the last global financial crisis.[101] It suggested Scottish taxpayers would each have £65,000 GBP of potential liabilities during a hypothetical bailout in Scotland, versus £30,000 GBP as part of the UK.[101] Economists including Andrew Hughes Hallett, Professor of Economics at St Andrews University, have rejected the idea that Scotland would have to underwrite these liabilities alone. He observed that banks operating in more than one country can be given a joint bailout by multiple governments.[102] In this manner, Fortis Bank and the Dexia Bank were bailed out collectively by France, Belgium, and the Netherlands.[102] The Federal Reserve System lent more than US$1 trillion to British banks, including $446 billion to the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), because they had operations in the United States.[102][103] Robert Peston reported in March 2014 that RBS and Lloyds Banking Group may be forced to relocate their head offices from Edinburgh to London in case of Scottish independence, due to a European law brought in after the 1991 collapse of the Bank of Credit and Commerce International.[104]

Weir Group, one of the largest private companies based in Scotland, commissioned a study by Oxford Economics into the potential economic effects of Scottish independence.[105] It found that larger companies such as Weir would lose through not being able to offset losses in Scotland against profits in the rest of the UK, even though the Scottish Government's proposal to cut corporation tax would mitigate this.[105] It also stated that independence would result in additional costs and complexity in the operation of business pension schemes.[105] The report found that 70% of all Scottish exports are sold to the rest of the UK, which it said would particularly affect the financial services sector.[105] Standard Life, one of the largest businesses in the Scottish financial sector, said in February 2014 that it had started registering companies in England in case it had to relocate some of its operations there.[106]

In February 2014, the Financial Times noted that Scotland's GDP per capita is bigger than that of France when a geographic oil and gas is taken into account, and still bigger than that of Italy when it is not.[107] As of spring 2014, Scotland has a lower rate of unemployment (6.5%) than the UK average (6.9%)[108] and a lower fiscal deficit (including as a percentage of GDP)[109] than the rest of the UK. Scotland performed better than the UK average in securing new Foreign Direct Investment in 2012–13 (measured by the number of projects), although not as well as Wales or Northern Ireland.[110] GDP growth during 2013 was lower in Scotland than in the rest of the UK, although this was partly due to an industrial dispute at the Grangemouth Refinery.[111]

Supporters of independence often claim that Scotland does not meet its full economic potential when subject to the same economic policy as the rest of the UK.[112][113] In 2013, the Jimmy Reid Foundation published a report that claimed UK economic policy had become "overwhelmingly geared to helping London, meaning Scotland and other UK regions suffer from being denied the specific, local policies they need". Margaret Cuthbert, the economist who authored the paper, said its conclusions were a direct challenge to the Better Together campaign, which says Scotland would be better off in the UK.[114] Later in January 2014, pro-independence politician Colin Fox also argued that Scotland is "penalised by an economic model biased towards the South East of England".[112] In November 2013, Chic Brodie MSP said that Scotland was "deprived" of economic benefit in the 1980s after the Ministry of Defence blocked oil exploration off the West of Scotland, ostensibly to avoid interference with the UK's nuclear weapons arsenal.[115]

Currency

Another economic issue is the currency that would be used by an independent Scotland.[116] The principal options are to establish an independent Scottish currency, join the European single currency, or retain the pound sterling.[116] Leading politicians in the rest of the UK have been sceptical or hostile towards the idea of a currency union, which would allow Scotland to retain the pound under a formal agreement with the rest of the UK. The Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne, stated that the UK would be unlikely to agree to such an arrangement, as it would compromise its sovereignty and open it up to financial risk.[117] Shadow Chancellor Ed Balls said the plans are "economically incoherent"[118] and that any currency option for an independent Scotland would be "less advantageous than what we have across the UK today",[119] though later invited Salmond to discuss the specifics of currency union with him ahead of the referendum.[120] Former Prime Minister Sir John Major has also rejected the idea of a currency union, saying it would require the UK to underwrite Scottish debt.[121]

If Scotland joined a currency union with the UK, some fiscal policy constraints could be imposed on the Scottish state.[116] Banking experts have argued that being the "junior partner" in a currency arrangement could amount to "a loss of fiscal autonomy for Scotland".[122] Dr Angus Armstrong of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research wrote that "An independent Scotland is likely to find the implicit constraints on economic policy, especially fiscal policy, are even more restrictive than the explicit ones it faces as a full part of the UK."[123] Salmond, however, has insisted an independent Scotland in a currency union would retain tax and spending powers.[124]

The Scottish Green Party has said that keeping the pound sterling as "a short term transitional arrangement" should not be ruled out, but the Scottish Government should "keep an open mind about moving towards an independent currency".[125] The Jimmy Reid Foundation produced a report in early 2013 that described retention of the pound as a good transitional arrangement, but recommended the eventual establishment of an independent Scottish currency to "insulate" Scotland from the UK's "economic instability". The report argued that the UK's monetary policy had "sacrificed productive economy growth for conditions that suit financial speculation" and that an independent currency could protect Scotland from "the worst of it".[126]

Gavin McCrone, former chief economic adviser to the Scottish Office, stated: "While I think it would be sensible for an independent Scotland to remain with sterling, at least initially, it might prove difficult in the long run; and, to gain freedom to follow its own policies, it may be necessary for Scotland to have its own currency."[127] However, he warned that this could lead to Scottish banks relocating to the UK.[127] The Scottish Socialist Party favours an independent Scottish currency pegged to the pound sterling in the short-term,[128] with its national co-spokesperson Colin Fox describing a sterling zone as "untenable"[129] as it leaves too much power with the UK state.[130] However, the party believes Scotland's currency should be determined in the first elections to an independent Scottish Parliament instead of in the referendum.[131] Other notable proponents of an independent Scottish currency include Yes Scotland chairman Dennis Canavan and former SNP deputy leader Jim Sillars.[132]

Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, the SNP's policy was that an independent Scotland should adopt the euro,[133] though this was relegated to a long-term rather than short-term goal by the party's 2009 conference.[134][135] There is disagreement over whether Scotland would be required to join the euro if it wished to become a European Union member state in its own right. All new members are required to commit to joining the single currency as a prerequisite of EU membership, but they must first be party to ERM II for two years. The Scottish Government argues that, as countries are not obliged to join ERM II, "the EU lacks any legal means of forcing Member States to comply with the pre-conditions that have to be satisfied before Eurozone membership is possible".[136] For example, Sweden has never adopted the euro. The people of Sweden rejected adopting the euro in a 2003 referendum and its government has subsequently stayed out by refusing to enter ERM II, membership of which is voluntary.[137][138]

At present, the SNP favours continued use of the pound sterling in an independent Scotland through a formal currency union.[139] In Scotland's Future, the Scottish Government identifies five key reasons it believes a currency union "would be in both Scotland and the UK's interests immediately post-independence":[140]

- the UK is Scotland's principal trading partner accounting for 2/3 of exports in 2011, whilst figures cited by HM Treasury suggest that Scotland is the UK's second largest trading partner with exports to Scotland greater than to Brazil, South Africa, Russia, India, China and Japan put together

- there is clear evidence of companies operating in Scotland and the UK with complex cross-border supply chains

- a high degree of labour mobility – helped by transport links, culture and language

- on key measurements of an optimal currency area, the Scottish and UK economies score well – for example, similar levels of productivity

- evidence of economic cycles shows that while there have been periods of temporary divergence, there is a relatively high degree of synchronicity in short-term economic trends

Yes Scotland maintains that a currency union would benefit both Scotland and the rest of the UK, as Scotland's exports, including North Sea oil, would boost the balance of payments and therefore strengthen the exchange rate of the pound sterling.[141] However, Professor Charles Nolan of the University of Glasgow has said that including Scottish exports in the balance of payments figures would make little difference because the pound is a floating currency. He said: "All that is likely to happen if the continuing UK loses those foreign exchange revenues is that the pound falls, boosting exports and curbing imports until a balance is once again restored."[142]

The Scottish Government has also claimed a currency union would benefit the rest of the UK as businesses in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland would otherwise face £500m in transaction costs while trading with Scotland,[143] which Plaid Cymru treasury spokesperson Jonathan Edwards agreed was a "threat to Welsh business".[144] The Welsh First Minister, Carwyn Jones, said that he would seek a veto on a currency union between Scotland and the rest of the UK, as having two governments in charge of it would be "a recipe for instability".[145] Alistair Darling said voters in the rest of the UK could choose not to be in a currency union with Scotland[146] and criticised the proposal by suggesting that Salmond was asserting that "everything will change but nothing will change".[147]

Government revenues and expenditure

The Barnett formula has resulted in higher public spending per head of population in Scotland than England.[148] If North Sea oil revenue is calculated on a geographic basis, Scotland also produces more tax revenue per head of population than the UK average.[149][150] The Institute for Fiscal Studies reported in November 2012 that a geographic share of North Sea oil would more than cover the higher public spending, but warned that oil prices are volatile and that it is a finite resource. The same report also warned that "If, as is likely, oil and gas revenues fall over the long run, then the fiscal challenge facing Scotland will be greater than that facing the UK.".[150] The Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland report for 2012/13 found that North Sea oil revenue had fallen by 41.5% and that Scotland's public spending deficit had increased from £4.6 billion to £8.6 billion.[151][152]

Given the uncertain nature of any independence agreement, matters such as what portion of the UK's public debt would be passed to Scotland, its credit rating and borrowing rates are also issues.[153][154] Fitch, a major credit rating agency, stated in October 2012 that it could not give an opinion on what rating Scotland would have, because the state of Scottish finances would largely depend on the result of negotiations between the UK and Scotland on the division of assets and liabilities.[154] Standard & Poor's, another significant credit rating agency, published a report in February 2014 that said Scotland would face "significant, but not unsurpassable" challenges, and that "even excluding North Sea output and calculating per capita GDP only by looking at onshore income, Scotland would qualify for our highest economic assessment".[155] Research published by Moody's in May 2014 said that an independent Scotland would be given an A rating, comparable with Poland, Czech Republic and Mexico.[156] An A rating would be two grades below its current Aa1 rating for the UK, which Moody's said would be unaffected by Scottish independence.[156]

European Union

The SNP advocates for a similar relationship between an independent Scotland and the European Union as between the UK and the EU today. This means full membership with some exemptions, such as not having to adopt the euro. There is debate over whether Scotland would be required to re-apply for membership, and if it could retain the UK's opt-outs.[157][158] The European Commission offered to provide an opinion to an existing member state on the matter, but the British Government confirmed it would not seek this advice on the ground that it did not want to negotiate the terms of independence ahead of the referendum.[159]

There is no direct precedent for part of a European Union member state seceding.[160] There are some relevant cases, but none of these are directly comparable.[160] Greenland joined the European Economic Community (EEC) as part of Denmark in 1973, but later voted for home rule and voted to leave the EEC.[160] The reunification of Germany in 1990 meant that the people of the former German Democratic Republic (East Germany) were added to the EEC.[160] Czechoslovakia split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia in 1993, with both new states joining the EU in 2004.[160] Supporters of independence have stated that an independent Scotland would become an EU member by treaty amendment under Article 48 of the EU treaties.[161] Opponents of independence argue that this would not be possible and that an independent Scotland would need to apply for EU membership under Article 49, which would require ratification by each member state.[161]

The former Prime Minister Sir John Major suggested in November 2013 that Scotland would need to re-apply for EU membership, but that this would mean overcoming opposition to separatists among many of the existing member states, particularly Spain.[162] Several media sources and opponents of independence have suggested that Spain may block Scottish membership of the EU, amid fears of repercussions with separatist movements in Catalonia and the Basque country.[162][163][164][165] In November 2013 the Spanish Prime Minister, Mariano Rajoy, said in an interview: "I know for sure that a region that would separate from a member state of the European Union would remain outside the European Union and that should be known by the Scots and the rest of the European citizens."[166] He also stated that an independent Scotland would become a "third country" outside the EU and would require the consent of all 28 EU states to rejoin the EU, but that he would not seek to block an independent Scotland's entry.[166] Salmond cited a letter from Mario Tenreiro of the European Commission's secretariat general that said it would be legally possible to renegotiate the situation of the UK and Scotland within the EU by unanimious agreement of all member states.[167] Professor Sir David Edward, a former European Court judge, has argued that the EU institutions and member states "would be obliged to enter into negotiations, before separation took effect, to determine the future relationship within the EU of the separate parts of the former UK and the other Member States. The outcome of such negotiations, unless they failed utterly, would be agreed amendment of the existing Treaties, not a new Accession Treaty."[158][168]

José Manuel Barroso, president of the European Commission, has suggested that an independent Scotland would have to apply for membership, but the rest of the UK would continue to be a member.[169] In a BBC interview he stated: "We are a union of states, so if there is a new state, of course, that state has to apply for membership and negotiate the conditions with other member states. For European Union purposes, from a legal point of view, it is certainly a new state. If a country becomes independent it is a new state and has to negotiate with the EU."[170] Christina McKelvie MSP, Convener of the European and External Relations Committee of the Scottish Parliament, wrote to Viviane Reding, Vice-President of the European Commission, in March 2014 to ask whether Article 48 would apply.[171] In her reply to McKelvie, Reding said that EU treaties would no longer apply to a territory when it secedes from a member state.[172] Reding also indicated that Article 49 would be the route to apply to become a member of the EU.[172] The former Taoiseach John Bruton has said that he believes Scottish membership would require a new treaty of accession ratified by all 28 member states.[173] "If an area were to secede from an existing EU member, that area would thereby cease to be a member of the EU. It would have to apply anew to become an EU member state, as if it had never been a member of the EU, and was applying for the first time."[174]

In January 2013, the Republic of Ireland's Minister of European Affairs, Lucinda Creighton, stated in an interview with BBC News that "if Scotland were to become independent, Scotland would have to apply for membership and that can be a lengthy process".[175] Creighton later wrote to Nicola Sturgeon to clarify that she understood her view was "largely in line with that of the Scottish Government", and that she "certainly did not at any stage suggest that Scotland could, should or would be thrown out of the EU".[176] In May 2013, Roland Vaubel, an Alternative für Deutschland politician,[177] published a paper titled The Political Economy of Secession in the European Union, which argued that Scotland would remain a member of the EU upon independence, and suggested there would need to be negotiations between the British and Scottish Governments on "how they wished to share the rights and obligations of the predecessor state". Vaubel also claimed that Barosso's comments on the status of Scotland after independence had "no basis in the European treaties".[178] In July 2013, Jakob Ellemann-Jensen, a member of the Danish Parliament's European Affairs Committee, and opposition party Venstre's spokesperson on European Affairs, said it would "only be natural for Denmark to acknowledge [Scotland's] independence and to welcome Scotland in both the EU in accordance with the Copenhagen Criteria and also in NATO". Lars Bo Kaspersen, Head of Political Science at the University of Copenhagen, added that he believed independence "could be a fairly quick transition". He continued: "I'm sure that the European Union in general would strongly support Scottish membership and the same goes for NATO. I can't think of anyone who wouldn't think it was a good idea."[179]

Future status of the United Kingdom in the European Union

In January 2013, the British Prime Minister, David Cameron, committed the Conservative Party to a referendum on the UK's membership of the European Union in 2017 if they win the 2015 general election,[180] seen largely as an appeal to the increasing number of UKIP supporters in England.[181] Legislation for this referendum has been approved by the House of Commons.[182] Studies have shown some divergence in attitudes to the EU in Scotland and the rest of the UK. Though a Scottish Government review based on survey data from between 1999 and 2005 found that people in Scotland reported "broadly similar Eurosceptic views as people in Britain as a whole",[183] Ipsos MORI noted in February 2013 that voters in Scotland said they would choose to remain in the EU in a referendum, "in contrast to November 2012 data on attitudes in England" where there was a majority for withdrawal.[184] Yes Scotland claimed that the UK government plans has caused "economic uncertainty" for Scotland.[185] SNP MSP Christina McKelvie said that she feared that Scotland would be "dragged out of the EU against our wishes".[186] Some commentators have suggested that the UK leaving the EU would undermine the case for Scottish independence, since free trade, freedom of movement and the absence of border controls with the UK could no longer be assumed.[187][188][189]

Monarchy

Some pro-independence political parties and organisations favour a republic, including the Scottish Green Party[190] and the Scottish Socialist Party.[191]

The SNP is in favour of retaining a personal union with the rest of the UK and would also seek membership of the Commonwealth of Nations.[116] First Minister Salmond has said the monarchy would be retained by an independent Scotland. Some figures within the SNP, including Christine Grahame, the convenor of the Scottish Parliament's Justice Committee, believe it is party policy to hold a referendum on the status of the monarchy,[192] owing to a 1997 SNP conference resolution to hold "a referendum in the term of office of the first independent Parliament of Scotland on whether to retain the monarch", but Salmond claims the policy has changed since then.[193]

Sport

Scotland will host the 2014 Commonwealth Games in Glasgow and the 2014 Ryder Cup in the months preceding the referendum. Scott Stevenson, the director of sport at Commonwealth Games Canada, said: "I'm pretty optimistic there'll be greater interest in Glasgow than some recent Games. I've asked in meetings [...] how we can expect the political issues to play out and that politics won't be put into the Games. Athletes want to come in and compete, unencumbered by politics."[194] The last Commonwealth Games hosted by Scotland, the 1986 event in Edinburgh, was boycotted by many countries due to British support for apartheid South Africa.[195]

During the 2012 Summer Olympics, Alex Salmond said that it would be Scotland's last appearance as part of Great Britain at the Olympics before it competes as an independent Scotland in the 2016 Summer Olympics.[196] International Olympic Committee representative Craig Reedie suggested that Scots would have to continue to represent Great Britain in 2016, as international recognition of an independent Scotland would not be immediately conferred.[197] He also questioned whether an independent Scotland could support its athletes to the same extent as Great Britain.[197] Scotsman and former Prime Minister Gordon Brown has pointed to the 2012 medal count for Great Britain, saying that it showed the success of a union that included the two nations.[198] Sir Chris Hoy suggested in May 2013 that it could "take time" for Scottish athletes to "establish themselves in a new training environment", indicating that the good performance of Scottish athletes as part of Team GB in the Olympics would not automatically translate into an independent Scottish Olympic team.[199] Hoy also said that he had made use of facilities at the National Cycling Centre in Manchester and that he believed the lack of facilities and coaching infrastructure in Scotland would have to be addressed by an independent state.[199]

Status of Orkney, Shetland and the Western Isles

The prospect of an independent Scotland has raised questions about the future of Orkney, Shetland and the Western Isles, three island groups off the coast of the Scottish mainland. Some islanders have called for separate referenda to be held in the islands on 25 September 2014, one week after the Scottish referendum.[200][201][202] In March 2014, the Scottish Parliament published the online petition it had received calling for such referenda.[203] The petition received support from Shetland MSP Tavish Scott.[203] The referenda would ask islanders to choose between three options: that the island group should become an independent country, that the island group should remain in Scotland, or (in the event that the result of the Scottish referendum was "yes") that the island group should not join an independent Scotland and would remain in the UK.[204]

The third option would implement the conditional promise made in 2012, when a spokesperson for the SNP said that in the event of Scottish independence, Orkney and Shetland could remain in the United Kingdom if their "drive for self-determination" was strong enough.[205] Politicians in the three island groups have referred to the Scottish referendum as the most important event in their political history "since the inception of the island councils in 1975". Angus Campbell, leader of the Western Isles, said that the ongoing constitutional debate "offers the opportunity for the three island councils to secure increased powers for our communities to take decisions which will benefit the economies and the lives of those who live in the islands".[206]

In a meeting of the island councils in March 2013, leaders of the three territories discussed their future in the event of Scottish independence, including whether the islands could demand and achieve autonomous status within either Scotland or the rest of the UK. Among the scenarios proposed were achieving either Crown Dependency status or self-government modelled after the Faroe Islands, in association with either Scotland or the UK.[207] Steven Heddle, Orkney's council leader, described pursuing Crown Dependency status as the least likely option, as it would threaten funding from the European Union, which is essential for local farmers.[207] Alasdair Allan, MSP for the Western Isles, said independence could have a positive impact on the isles, as "crofters and farmers could expect a substantial uplift in agricultural and rural development funding via the Common Agricultural Policy if Scotland were an independent member state of the EU".[208]

Early in 2013, an opinion poll commissioned by the Press and Journal found only 8% of people in Shetland and Orkney supported the islands themselves becoming independent countries, with 82% against and a further 10% did not know.[209] In July 2013, the Scottish Government made the Lerwick Declaration, indicating an interest in devolving power to Scotland's islands. By November, it had made a commitment during a meeting with council leaders to devolve further powers to Orkney, Shetland and the Western Isles in the event of independence.[210] Steven Heddle, convenor of Orkney Islands Council, called for legislation to that effect to be introduced regardless of the referendum result.[211]

United Nations

David Cameron has suggested an independent Scotland would be "marginalised" at the United Nations, where the UK is a permanent member of the Security Council.[212] John Major has suggested that, after Scottish independence, the remaining UK could lose its permanent seat at the UN Security Council.[213]

Universities

Scientific research

In 2012–13, Scottish universities received 13.1% of Research Councils UK funding.[214] Dr Alan Trench of University College London has said that Scottish universities receive a "hugely disproportionate" level of funding and would no longer be able to access it following independence. Willie Rennie, leader of the Scottish Liberal Democrats, has suggested that independence would mean Scottish universities losing £210m in research funding.[215] The Institute of Physics in Scotland warned that access to internationally renowned facilities such as the CERN Large Hadron Collider, the European Space Agency, and European Southern Observatory could require renegotiation by the Scottish Government.[216] It also said an independent Scotland would need to consider how funding from influential UK charities such as the Wellcome Trust and the Leverhulme Trust would be maintained, and there are "major uncertainties" about how international companies with bases in Scotland would view independence.[216]

The Scottish Government's Education Secretary, Michael Russell, has said that Scotland's universities have a "global reputation" that would continue to attract investment after independence.[217] In September 2013, the principal of the University of Aberdeen said that Scottish universities could continue to access UK research funding through a "single research area" that crossed both nations' boundaries.[218] Professor David Bell, professor of economics at the University of Stirling, said that cross-border collaboration might continue, but Scottish universities could still lose their financial advantage.[219] Roger Cook of the Scotland Institute pointed out that although Scottish universities do receive a higher share of Research Councils funding, they are much less dependent on this as a source of funding than their counterparts in England.[87]

Student funding

Tuition fees for students domiciled in Scotland were abolished in 2001.[220] The fees were replaced by a a system of graduate endowments, which were themselves abolished in 2008.[220][221] Tuition fees are charged for students domiciled in the rest of the United Kingdom, where universities are allowed to charge fees of up to £9,000 per annum.[222] Fees are not charged by Scottish universities to students from other European Union (EU) member states in order to comply with the European Convention on Human Rights.[223]

If Scotland became an independent state, students from the rest of the United Kingdom would then be in the same position as students from the rest of the EU presently are.[222] A study by the University of Edinburgh found that this would cause a loss in funding and could potentially squeeze out Scottish students.[222] The study suggested three courses of action for an independent Scotland: introducing tuition fees for all students; negotiate an agreement with the EU where a quota of student places would be reserved for Scots; or introducing a separate admissions service for students from other EU member states, with an admission fee attached.[222] It concluded that the EU may allow a quota system for some specialist subjects, such as medicine, where there is a clear need for local students to be trained for particular careers, but that other subjects would not be eligible.[222] The study also found that their third suggestion, of charging different fees for students from other states would run against the spirit of the Bologna agreement, which aims to encourage student mobility throughout the EU.[222]

The Scottish Government stated in its white paper, Scotland's Future, that the present tuition fees arrangement would remain in place in an independent Scotland, as the EU allows for different fee arrangements in "exceptional circumstances".[224] Jan Figel, a former EU commissioner for education, said in January 2014 that it would be illegal for an independent Scotland to apply a different treatment to students from the rest of the UK.[225] A report by a House of Commons select committee stated that it would cost an independent Scottish Government £150 million to provide free tuition to students from the rest of the UK.[224] A group of academics campaigning for independence has expressed concern that the present arrangements would not continue if Scotland stayed within the UK, due to public spending cuts in England and the consequential effects of the Barnett formula.[226]

Welfare

The Yes campaign has argued that control of welfare policy would be a major benefit of independence.[227] According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, independence would "give the opportunity for more radical reform, so that the [welfare] system better reflects the views of the Scottish people".[228] Yes Scotland and Deputy First Minister Nicola Sturgeon have said the existing welfare system can only be guaranteed by voting for independence.[229][230] In September 2013, the Scottish Council for Voluntary Organisations (SCVO), which represents charities, called for a separate welfare system to be established in Scotland.[231]

In November 2013, the Scottish Government pledged to use the powers of independence to reverse key aspects of the Welfare Reform Act 2012, which was implemented across the UK despite opposition from a majority of Scotland's MPs. It said it would abolish Universal Credit[232] and the bedroom tax.[233] The SNP has also criticised Rachel Reeves, Labour's Shadow Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, for saying[234] a future UK Labour government would be even tougher on benefits than the Cameron ministry.[235][236]

In January 2012, sources close to the Prime Minister told The Scotsman that "a unified tax and benefit system is at the heart of a united country" and that these powers could not be devolved to Scotland after the referendum,[237] though Liberal Democrat Michael Moore said in August 2013 that devolution of parts of the welfare budget should be "up for debate".[238] Labour politician Jim Murphy, a former Secretary of State for Scotland, has argued that he is "fiercely committed" to devolving welfare powers to the Scottish Parliament, but also warned that independence would be disruptive and would not be beneficial.[239] Scottish Labour’s Devolution Commission recommended in March 2014 that some aspects of the welfare state, including housing benefit and attendance allowance, should be devolved.[240]

Responses

Demonstrations

A number of demonstrations in support of independence have been co-ordinated since the announcement of the referendum. The March and Rally for Scottish Independence in September 2012 drew a crowd of between 5,000 and 10,000 people to Princes Street Gardens.[241] The event was repeated in September 2013; police estimated that over 8,000 people took part in the march, while organisers and the Scottish Police Federation[242] claimed between 20,000 and 30,000 people took part in the combined march and rally.[243] The March and Rally was criticised in both 2012 and 2013 for the involvement of groups like the Scottish Republican Socialist Movement[244] and Vlaamse Volksbeweging.[245]

Debates

Debates over the issue of independence have taken place on television, in communities, and within universities and societies since the announcement of the referendum.[246][247][248][249][250] The current affairs programme Scotland Tonight has televised a series of debates: Sturgeon v Moore,[251] Sturgeon v Anwar,[252] Sturgeon v Carmichael[253] and Sturgeon v Lamont.[254] On 21 January 2014, BBC Two Scotland broadcast the first in a series of round-table debates, which was filmed in Greenock and chaired by James Cook.[255][256]

The Yes campaign has repeatedly called for there to be a televised debate between UK Prime Minister David Cameron and First Minister of Scotland Alex Salmond. These calls for a one-on-one debate have been dismissed by Cameron[257][258] on the basis that the referendum is "for Scots to decide" and the debate should be "between people in Scotland who want to stay, and people in Scotland who want to go".[259] Salmond has likewise been accused of "running scared" from debating with Better Together chairman Alistair Darling instead,[260] although Sturgeon stated in October 2013 that a Salmond–Darling debate would take place at some point.[261] Darling has refused a public debate with Yes Scotland chairman Blair Jenkins.[262] In April 2014, UKIP leader Nigel Farage challenged Alex Salmond to debate, but Farage was dismissed by an SNP spokeswoman as “an irrelevance in Scotland”.[263]

Opinion polling

Professor John Curtice stated in January 2012 that polling showed support for independence at between 32% and 38% of the Scottish population, a slight decline from 2007, when the SNP first formed the Scottish Government.[264] To date there has been no poll evidence of majority support for independence, although the share "vehemently opposed to independence" has declined.[264] According to Curtice, the polls were remarkably stable during most of 2013, with the "no" camp leading by an average of 50% to 33% for "yes" with one year to go.[265] American polling expert Nate Silver said in August 2013 that the yes campaign had "virtually no chance" of winning.[266] The polls tightened in the months after the release of the Scottish Government white paper on independence, with an average of five polls in December 2013 and January 2014 giving 39% support for yes.[267] The polls again tightened after George Osborne stated in February that the UK Government was opposed to a currency union, with the average yes support increasing to 43%.[268]

See also

- Constitution of the United Kingdom

- History of Scottish devolution

- History of the Scottish National Party

- Politics of the United Kingdom

References

- ^ Bicker, Laura (2 April 2014). "Scottish independence: Voter registration 'highest ever'". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Scotland to hold independence poll in 2014 – Salmond". BBC News. BBC. 10 January 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Agreement between the United Kingdom Government and the Scottish Government on a referendum on independence for Scotland" (PDF). 15 October 2012. Retrieved May 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Response to referendum consultation". Scotland.gov.uk. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ^ "Scottish Independence Referendum Bill". Scottish.parliament.uk. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ Text of the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ Government accepts all Electoral Commission recommendations. Scotland.gov.uk (30 January 2013).

- ^ a b "The 1979 Referendums". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ a b "Scottish Referendum Live – The Results". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ "Scottish Parliament Official Report – 12 May 1999". Scottish Parliament.

- ^ "Manifesto 2007" (PDF). Scottish National Party. 12 April 2007. pp. 8, 15. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Timeline: Scottish independence referendum". BBC News. BBC. 15 October 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ "Annex B Draft Referendum (Scotland) Bill". Official website, Publications > 2007 > August > Choosing Scotland's Future: A National Conversatio > Part 10. Scottish Government. 13 August 2009. Archived from the original on 10 September 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- ^ a b c Quinn, Joe (30 November 2009). "SNP reveals vision for independence referendum". London: The Independent. Archived from the original on 30 November 2009. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

- ^ "Your Scotland, Your Voice". www.scotland.gov.uk > News > News Releases > 2009 > November > YSYV. Scottish Government. 30 November 2009. Archived from the original on 30 November 2009. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

- ^ "Scottish independence referendum plans published". BBC News. 25 February 2010. Archived from the original on 25 February 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ^ "Referendum consultation". www.scotland.gov.uk > News > News Releases > 2010 > February > referendum. Scottish Government. 25 February 2010. Archived from the original on 25 February 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Scotland's Future: Draft Referendum (Scotland) Bill Consultation Paper". www.scotland.gov.uk > Publications > 2010 > February > Scotland's Future: Draft Referendum (Scotland) Bil > PDF 1. Scottish Government. 25 February 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ^ a b "Draft Referendum (Scotland) Bill Consultation". www.scotland.gov.uk > Topics > Public Sector > Elections > Referendum Bill Consultation. Scottish Government. undated. Archived from the original on 25 February 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Black, Andrew (3 September 2009). "Q&A: Independence referendum". BBC News. Archived from the original on 10 September 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- ^ MacLeod, Angus (3 September 2009). "Salmond to push ahead with referendum Bill". London: The Times. Archived from the original on 10 September 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- ^ "Scottish independence plan 'an election issue'". BBC News. BBC. 6 September 2010. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ^ Stuart, Gavin (14 April 2011). "SNP launch 'Re-elect' manifesto with independence referendum vow". STV. STV Group. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ^ Black, Andrew (1 May 2011). "Scottish election: Party leaders clash in BBC TV debate". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ^ "Scottish election: SNP wins election". BBC News. BBC. 6 May 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ^ a b c Clegg, David (17 January 2012). "Advocate General says SNP's referendum plans would be 'contrary to the rule of law'". The Courier. DC Thomson. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ^ a b Clegg, David (11 January 2012). "Independence referendum: Scotland facing constitutional chaos". The Courier. DC Thomson. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ^ Text of the Scottish Independence Referendum (Franchise) Act 2013 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ a b c "Scottish independence: Referendum White Paper unveiled". BBC News. 26 November 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ^ Severin Carrell and Nicholas Watt (10 January 2012). "Scottish independence: Alex Salmond sets poll date – and defies London | Politics". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ^ a b "Bannockburn date mooted for referendum". Herald Scotland. 2 January 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ^ "Scotland's referendum: If at first you don't succeed". The Economist. 14 January 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ^ "Viewpoints: Can 16- and-17-year olds be trusted with the vote?". BBC News. BBC. 14 October 2012. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ Macdonnell, Hamish (17 September 2011). "16-year-olds likely to get the vote on Union split". The Times Scotland. London: Times Newspapers Limited. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ^ "Scottish independence: Bill to lower voting age lodged". BBC News. 12 March 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ "Scottish independence: Referendum voting age bill approved by MSPs". BBC News. 27 June 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Scottish independence: SNP dismisses ex-pat voting call". BBC News. BBC. 18 January 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- ^ "Ulster Scots and Scottish independence". BBC News. 16 October 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ Whitaker, Andrew (18 January 2012). "Scottish independence referendum: Publish legal advice or be damned, SNP warned over referendum". The Scotsman. Johnston Press. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- ^ a b "Scottish independence: Referendum vote 'needs approval'". BBC News. BBC. 20 January 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Black, Andrew (30 January 2013). "Scottish independence: SNP accepts call to change referendum question". BBC Sport. BBC. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ^ a b http://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/153689/Ipsos-MORI-Scotland-question-testing-report-24-January-2013.pdf

- ^ a b Matthews, Kyle (1 April 2014). "Obstacles to Independence in Quebec". www.opencanada.org. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ^ Barnes, Eddie (14 October 2012). "Scottish independence: Salmond in campaign cash battle". Scotland on Sunday. Johnston Publishing. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ Adams, Lucy (1 May 2014). "Scottish independence: Questions raised over campaign spending rules". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ "Scottish independence: Referendum cost estimated at £13.3m". BBC News. BBC. 3 April 2013. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ^ a b "Scottish independence: Alistair Darling warns of 'no way back'". BBC News. BBC. 25 June 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Scottish independence: One million Scots urged to sign 'yes' declaration". BBC News. BBC. 25 May 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ "Scottish independence: Greens join Yes Scotland campaign". BBC News. BBC. 6 October 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ^ "Scottish independence: Yes Scotland signs up 143,000 supporters". BBC News. 30 November 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ^ "Yes Scotland hail 372,000 Independence Declaration signatures". 24 May 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ^ a b Bicker, Laura (29 April 2014). "Scottish independence: Farmers give their views on referendum debate". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, Colletta (29 April 2014). "Scottish independence:How might a 'Yes' vote impact on farmers?". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ a b c Carrell, Severin (14 March 2014). "Theresa May would seek passport checks between Scotland and England". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ a b "Scotland citizenship, passport plans outlined". The Scotsman. Johnston Publishing. 26 November 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ "Key questions on independence white paper answered". The Scotsman. Johnston Publishing. 27 November 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ "SNP's Clyde warships plan". 3 July 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ^ "Defence committee - membership". Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ a b Morris, Nigel (27 September 2013). "Alex Salmond's SNP plans for Scottish independence criticised for lacking crucial detail over defence plans". The Independent.

- ^ "SNP defence plans slammed". Left Foot Forward. 27 September 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ Cramb, Auslan (13 November 2013). "A budget of £2.5 billion will not buy Scottish Defence Force wishlist, warns defence minister". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ "A' the Blue Bonnets: Defending an Independent Scotland". www.rusi.org. Royal United Services Institute. 15 October 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ "Irish lesson for independent Scottish forces". 14 April 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ "How would an independent Scotland defend itself?". The Guardian.

- ^ "UK caught "red-handed" on Scotland's underspend". 21 January 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ "SNP anger as seven Scottish TA bases set to close". 3 July 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ^ "Scotland's Future". Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ "Scotland's Future". Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ "Scotland's Future". Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ Richard Norton-Taylor (29 January 2012). "Trident nuclear deterrent 'at risk' if Scotland votes for independence". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 October 2012.